Surgical techniques and postoperative management to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery

2019-08-12HiromichiKawaidaHiroshiKonoNaohiroHosomuraHidetakeAmemiyaJunItakuraHidekiFujiiDaisukeIchikawa

Hiromichi Kawaida, Hiroshi Kono, Naohiro Hosomura, Hidetake Amemiya, Jun Itakura, Hideki Fujii,Daisuke Ichikawa

Abstract Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is one of the most severe complications after pancreatic surgeries. POPF develops as a consequence of pancreatic juice leakage from a surgically exfoliated surface and/or anastomotic stump, which sometimes cause intraperitoneal abscesses and subsequent lethal hemorrhage. In recent years, various surgical and perioperative attempts have been examined to reduce the incidence of POPF. We reviewed several well-designed studies addressing POPF-related factors, such as reconstruction methods, anastomotic techniques, stent usage, prophylactic intra-abdominal drainage, and somatostatin analogs, after pancreaticoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy, and we assessed the current status of POPF. In addition, we also discussed the current status of POPF in minimally invasive surgeries, laparoscopic surgeries, and robotic surgeries.

Key words: Postoperative pancreatic fistula; Pancreaticoduodenectomy;Pancreatojejunostomy; Pancreatogastrostomy; Distal pancreatectomy; Prophylactic drainage; Somatostatin analogs

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of pancreatic cancer has increased in both Asian and Western countries.Surgical resection is the cornerstone of treatment for this aggressive disease. With advances in surgical techniques and perioperative management, the operative mortality of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) in high-volume centers has decreased to less than 3%[1-3]. Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), however, develops frequently, and previous prospective studies have reported an incidence of more than 10%[4-7]; therefore, POPF is the most frequent lethal complication after pancreatectomy,regardless of the type of procedure.

POPF is believed to be primarily caused by the leakage of pancreatic juice into the abdomen; it can lead to intraperitoneal abscesses and also occasional hemorrhage,which cause life-threatening conditions with mortality rates of up to 40%[4,6,7-11]. In clinical practice, various ingenuities have been attempted to prevent the development of POPF, and some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to compare different optional procedures.

In this review, we aimed to summarize the current status of POPF in pancreatic surgery and to present the recent findings of the reconstruction methods of PD, stump closure methods of distal pancreatectomy (DP) and evidence for the risk factors and preventive treatment for the development of POPF.

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Pancreatic fistula was defined by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula(ISGPF) in 2005[12]and was revised in 2016[4]. The ISGPF’s definition divides pancreatic fistula into biochemical fistula and clinically significant POPF.

A grade A POPF is called a biochemical fistula and is defined as measurable fluid output on or after postoperative day 3, with an amylase content higher than three times the upper normal serum level; a grade A POPF has no clinical impact on the normal postoperative pathway. Clinically significant POPFs are classified as grades B and C. A grade B POPF requires one of the following conditions: an endoscopic or radiological intervention, a drain in situ for > 3 wk, clinical symptoms without organ failure, or clinically relevant change in POPF management. Whenever a major change in clinical management or deviation from the normal clinical pathway is required or organ failure occurs, the fistula shifts to a grade C POPF[4,6].

Following this definition, the incidence of clinically significant POPF has been reported to vary from approximately 1% to 36%[4,6,7,12-17]. There are different causes related to the development of POPF in the PD and distal pancreatectomy (DP)[18]procedures, and the incidence is generally recognized to be relatively higher in DP than in PD. Therefore, we discuss recent findings and evidence of POPF in PD and DP separately as described later in this review.

PANCREATICODUODENECTOMY

PD remains the only curative treatment option for malignant and some borderline/benign tumors of the pancreatic head and periampullary region even though the excessive invasive procedure is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. One of the most important factors of morbidity and mortality following PD is the incidence of POPF. Many previous studies have reported several risk factors in PD, such as gender (male)[19], BMI > 25 kg/m2[20], anastomotic method[6,21], external stent[22], fasting blood glucose level < 108.0 mg/dL[23], etc. However, the most reliable consensus risk factors for POPF after PD are small pancreatic duct (≤ 3 mm) and soft pancreas[6,21,23-28], which reflect the possibility that adequate anastomosis of the pancreatic duct and active exocrine function are deeply involved in the development of POPF. Therefore, various surgical techniques have been attempted to prevent POPF.

Reconstruction methodsIdentifying the best anastomosis technique for pancreatic surgery has remained controversial thus far. Of the several available techniques, pancreaticogastrostomy(PG) and pancreatojejunostomy (PJ) are the most commonly performed. Some RCTs[28-35]and meta-analyses[36-44]have compared PG and PJ. Topal et al[32]reported comparative results of the occurrences of POPFs (grade B or C) in an RCT with 329 patients. They stratified the randomization according to the pancreatic duct diameter,and the results clearly demonstrated that the occurrence of POPF was significantly lower after PG than after PJ (OR = 2.86; 95%CI: 1.38-6.17; Ρ = 0.02). Conversely, a recent German multicenter RCT[35]demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the rate of grade B/C fistulas after PG vs PJ (20% vs 22%, respectively, Ρ= 0.617). Each RCT has variable eligibility criteria for patients with diseases and suture methods for reconstruction; therefore, their conclusions should be interpreted with caution.

Several meta-analysis results on this issue have been reported and demonstrated the apparent superiority of PG in the risk for POPF despite the slight difference in the included studies[36-44]. However, PJ was found to have physiological advantages compared to PG although the follow-up periods were relatively short[34,45-48].

In recent retrospective studies, a significantly higher postoperative atrophic change of the pancreatic parenchyma and frequent severe steatorrhea were reported in the PG group during long-term follow-up periods[45-48]. Additionally, a higher frequency of impaired glucose tolerance after PG has been reported compared to PJ during the follow-up period. Considering the function of the remnant pancreas, the use of only short-term results is not sufficient for comparison[34,49].

Reconstruction after pancreatic surgery remains under debate, and it is impossible to confidently conclude which method is better after PD. Therefore, the reconstruction method should be determined based on the patient and tumor characteristics, such as pancreatic duct diameter, consistency of pancreas, and oncological prognosis (Table 1).

Anastomotic techniquesIn recent years, several simple and facilitating surgical anastomotic techniques have been reported.

A transpancreatic U-suture technique was devised by Blumgart et al[50], and the ratio of clinically relevant PFs was reported to be only 6.9% in the original report.Other researchers have conducted confirmatory studies and reported that the occurrence rates of POPFs were less than 5%[51,52]. Furthermore, favorable short-term outcomes have been achieved by some modifications of the novel technique. Fujii et al[53]reported on the modified Blumgart’s method. The differences between the original and modified method are described below. The original Blumgart’s method used four to six transpancreatic jejunal seromuscular U-shaped sutures to approximate the pancreas and the jejunum[50], whereas the modified Blumgart’s method used only one to three sutures. In the original method, the sutures were tied at the pancreatic wall, whereas the sutures were tied at the ventral wall of the jejunum in the modified method. The results showed that the ratio of clinically relevant POPFs was significantly lower after the modified Blumgart’s method than after Kakita’s method (2.5% vs 36%, respectively)[53]. However, other studies did not confirm the superiority of the Blumgart or modified Blumgart’s methods in preventing POPFs compared to Kakita's method or conventional interrupted sutures[54,55].

The most beneficial feature of duct-to-mucosa PJ is the secure drainage of pancreatic juice into the intestinal lumen. The anastomotic procedure, however, is not always easy, particularly with narrow pancreatic ducts. An invagination method in which the cross-sectional surface was inserted into the intestinal lumen might be a substitutive option of duct-to-mucosa PJ as an easier reconstruction method.

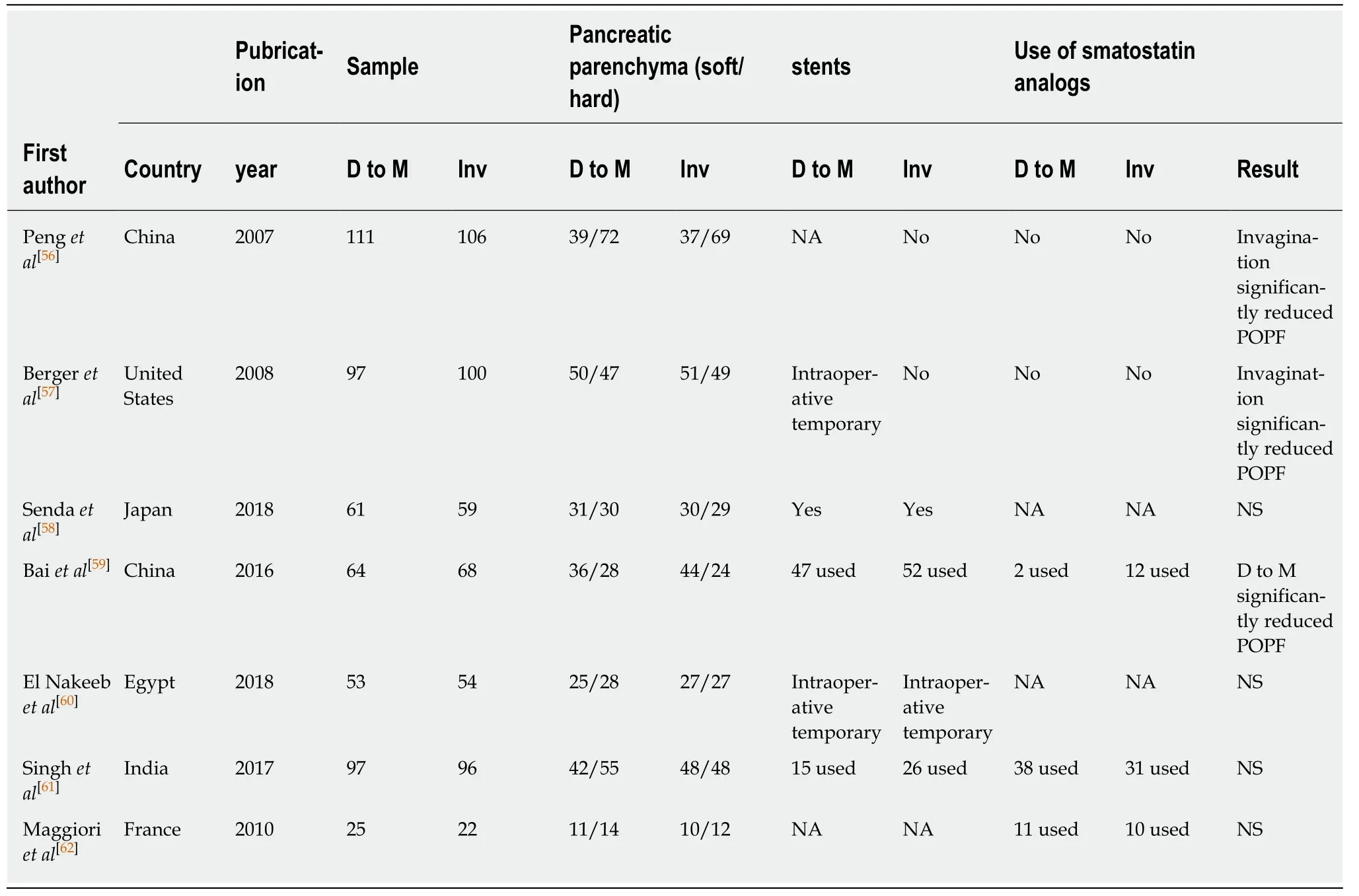

Nearly a decade ago, two types of invagination methods were examined to reduce POPF after PD in large-scale RCTs[56-62](Table 2). Peng et al[56]performed binding PJ, in which the stump of the jejunum was everted and the remnant of the pancreas and the everted jejunum were anastomosed in a circular fashion; finally, the everted jejunum was restored to wrap over the pancreatic stump. Conversely, Berger et al[57]performed invagination PJ in endo-to-side anastomosis. Both RCTs clearly revealed significantly decreases in POPF rates in invagination PJ compared to conventional duct-to-mucosa PJ; likewise, the tendency was more remarkable in soft pancreases compared to hard pancreases. Recently, however, several RCTs were unable to confirm the superiority in POPF rates with invagination PJ. Although RCTs are recognized to provide the most reliable results suggesting future evidence-based medicine, the results could be affected by many factors, including patient-related, tumor-related, and surgeon-related factors. In fact, for patient-related factors, Senda et al[57]indicated the possibility of reducing POPFs in invagination PJ for high risk patients with a soft pancreas although they revealed the non-superiority of invagination over duct-tomucosa PJ with the risk of POPF as their primary endpoint. To overcome surgeonrelated factors, Bai et al[59]conducted a similar RCT in which all procedures were performed by the same surgeon. They demonstrated that the overall POPF and morbidity rates were similar between invagination and duct-to-mucosa PJ; however,clinically relevant POPFs and severe complications were more frequent in the invagination PJ group.

Some meta-analyses were conducted concerning the superiority of invagination PJ on the rate of POPFs and demonstrated that invagination PJ did not reduce POPF rates and other adverse events compared to duct-to-mucosa PJ[63,64]; however, many of the analyzed studies were heterogeneous in several respects. The duct-to-mucosa PJ was performed by the conventional anastomotic technique, and therefore,invagination PJ does not appear significantly better than the current duct-to-mucosa PJ with respect to the incidence of POPF for low risk patients at least.

Stent or no-stentAnother concern is the necessity of stent placement for PJ anastomosis, whether a stent should be used, and whether the stent should be external or internal stent. Nonstent PJ anastomosis is the ideal and physiologically favorable procedure because stenting is sometimes associated with tube-related complications, digestive fluid loss,and subsequently impaired digestive and absorptive functions with external stents.Several previous studies, however, have reported that draining the pancreatic juice from the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis with a stent placed in the main pancreatic duct is an effective method to promote the healing of the anastomotic site by preventing pancreatic trypsin from corroding the anastomotic site during the early period after surgery, thereby reducing the rate of POPFs after PD[65,66].

Several RCTs have been conducted to examine the short-term outcomes of patients with external or internal stents compared to those without stents after PJ[65-69].However, there were no differences in the incidence of POPFs or other morbidities between the stent (external or internal) and the no-stent groups. One meta-analysis reported that an external stent for PJ decreased the rates of POPFs[70]; however,another recent comprehensive systematic review with a meta-analysis reported that there was no significant difference in the rates of POPFs, in-hospital mortality, reoperation, delayed gastric emptying, wound infection, and intra-abdominal abscesses between the stent and no-stent groups. They only found that the postoperative overall morbidity was lower and the total hospital stay was shorter in the external stent group compared to the no-stent group[71].

Table 2 Characteristics and intraoperative data of 7 randomized controlled trials included studies comparing invagination vs duct-tomucosa

Other studies have reported comparable results in POPFs between external and internal stents for PJ anastomosis. Compared to an internal stent, an external stent has the advantage of more complete diversion of pancreatic juice from the PJ anastomosis and the prevention of activation of pancreatic enzymes by bile juice[66]. However, there are shortcomings of more surgical procedures, liquid loss, and the risk of local peritonitis after removal of the stent tube[72]. Moreover, an external stent may develop tube-related complications, kinks, and obstructions[73]. Wang et al[74]reported that the length of pancreas juice in the stent tube was the predicting factor for clinical POPF.Internal drainage with a stent is considered one of the optimal methods to avoid exposing pancreatic juice to the PJ anastomosis without digestive fluid loss and impaired digestive and absorptive function[72,73,75]. However, the real-time drainage status of pancreatic juice cannot be monitored, and the stent rarely migrates into the bile duct with internal stents. Several RCTs have reported that internal stents tend to reduce the POPF ratio compared to external stents; however, no difference was observed in the incidence of POPF between the two stent methods[76-78]. This is also reported in past RCTs that internal stents did not reduce the POPF ratio compared to non-stents[79,80].

Almost all of the previous studies were conducted in single centers. Therefore,additional multicenter RCTs comparing the efficacy of external pancreatic duct stenting versus internal pancreatic duct stenting versus non-stenting must be performed, particularly for cases with a soft pancreas.

The use of surgical tissue adhesivesSeveral studies evaluated the effect of topical application of fibrin glue applied to the pancreatic anastomosis[81-85]. When a pancreatic tissue tearing occurred, it was expected to be covered by the fibrin sealant. Although there was also a report that evaluated the effect[81], most reports concluded that fibrin sealants might have no effect on POPF in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy[82-85].

Also, omental wrapping was expected to reduce the incidence of the POPF and intra-abdominal hemorrhage[86,87]. Although there have been reports of reduced intraabdominal complications, this method did not significantly reduce POPF[86-89].

DISTAL PANCREATECTOMY

The primary indications for DP include both benign and malignant tumors of the pancreatic body and tail. Although the mortality associated with DP has decreased in recent decades because of improvements in operative techniques and perioperative managements, morbidity remains high. The most ominous complication is POPF,which may cause life-threatening conditions. The incidence of clinical POPF (Grade B or C) after DP ranged from 5% to 40%[20,21,90-96]; this rate is higher than that after PD.However, POPFs that occur after DP are usually clinically less severe compared to those that occur after PD[97,98]. Various surgical techniques that involve transecting the pancreatic parenchyma have been attempted to reduce the incidence of POPF after DP. In recent years, these techniques include hand-sewn closure and stapler closure.

Numerous risk factors for POPF after DP have been previously reported,particularly pancreatic thickness[21,91-93,98], age[90,93], and BMI[90,94,96,99]. In patients with a thick pancreas, the stapler method may crush the pancreas parenchyma, which leads to the breakage of small pancreatic ducts and causes the development of POPF[99]. BMI may influence the physiological condition of the pancreas because fibrosis or fatty changes may occur[92]. In any case, the most important factor to reduce the incidence of POPF is to close the stump of the remnant pancreas completely at the time of surgery.

Stump closure methodsRecently, the most commonly used techniques for stump closure are hand-sewn closure or stapler closure. Hand-sewn closure is a common technique that involves suturing the pancreatic stump in a fish-mouth fashion after ligating the main pancreatic duct. Conversely, the stapler method has become a widely used technique for pancreatic stump closure in recent years because of its convenience. Zhou et al[100]performed a meta-analysis comparing stapler versus hand-sewn closure of the pancreatic stump; they described that indicate the superiority of the stapler method(22.1% vs 31.2%) although it did not reach statistical significance. However, in a multicenter randomized DISPACT trial that was conducted among 21 centers in Europe in 450 randomized patients (of whom 296 were analyzed), the stapler closure method did not reduce the incidence of POPF compared to hand-sewn closure for DP(stapler closure, 32% vs hand-sewn closure, 28%)[101]. Although the occluded areas of the stapler develop local necrotizing pancreatitis and may cause POPF[99], the stapler method is used as the standard technique. However, this technique experiences difficulties when the cutting line of the pancreas is on the right side of the portal vein.

To reinforce the staple line, RCTs assessing the use of several different materials have been reported. Three RCTs and one meta-analysis attempted to demonstrate the effect of reinforcement with an absorbable fibrin sealant patch (TachoSil®) over the pancreatic stump[102-106]. This technique was unable to reduce POPFs compared to conventional methods of the stapler only. However, Montorsi et al. reported that the amylase level of the drainage fluid was significantly lower in the TachoSil® group on day 1[104]. This result suggests that TachoSil® may be useful in sealing the cutting line of the pancreas. However, many reports described that fibrin sealants might lead no difference in POPF[82].

The DISCOVER trial was conducted to investigate the technique of remnant pancreatic reinforcement by use of a teres ligament patch to prevent POPF. Although this clinical trial was unable to significantly reduce the rate of POPFs (Ρ = 0.1468), the rates of clinically relevant POPFs with coverage and without coverage were 22.4%and 32.9%, respectively, resulting in a 10% reduction in clinical POPF[106].

A reinforced stapler (REINF) with bioabsorbable materials is used with the expectation of further effects. Kawai et al[107]clarified the safety of the REINF for pancreatic stump closure during DP. A 2013 meta-analysis including five retrospective and five prospective studies compared staplers without reinforcement(STPL) vs REINF. Although the incidence of POPF was 24% and 17%, respectively,and tended to be lower in REINF, the superiority of reinforcement was not proven[108].Additionally, a recent RCT reported that REINF significantly reduced POPF to a clinically relevant degree compared to STPL (11.4%, and 28.3%, respectively)[109].Conversely, Kondo et al. reported that REINF for pancreatic stump closure during DP does not reduce the incidence of clinically relevant PF compared to STPL. However, in patients with a pancreatic transection line thickness of less than 14 mm, a significant difference was shown in the incidence of clinically POPF (4.5% vs 21.0% in the reinforced stapler vs. bare stapler groups, respectively, Ρ =0.01)[110]. Jensen et al[108]reported that polyglycolic acid mesh induces an inflammatory reaction immediately after insertion, and this may promote adhesion and prevent leakage of pancreatic juice from the cutting line of the remnant pancreas. As described above, although the efficacy of REINF has not been sufficiently proven, the incidence of POPF tends to decrease compared to previous techniques.

Pancreatoenteral anastomosisThree retrospective studies have demonstrated that pancreatoenteral anastomosis(PE) of the pancreatic stump significantly reduced POPFs compared to stump closure only[111-113]. In these reports, the main pancreatic duct was ligated in both groups, and the anastomosis of the PE was performed by the invagination method. Octreotide was administered in two of these studies[107,109], and in the other study, PJ and PG were both performed in the PE group and hand-sewn closure and stapler closure were both performed in the stump closure group[112]. Additionally, the rate of postoperative hemorrhage was high in all reports. However, the statistical power of these studies was limited because of the small sample size of patients.

Two recent RCTs have been reported. Kawai et al[114]compared PJ of the pancreatic stump with the stapler without reinforcement method. In this study, anastomosis was performed in a non-stented duct-to-mucosa fashion using a single layer of interrupted absorbable suture and the addition of a seromuscular-parenchymal anastomosis.However, the ratio of POPFs in PJ tends to be lower than that in stapler closure, but the difference is not significant. Furthermore, Uemura et al. investigated whether PG of the pancreatic stump reduced clinical POPFs compared to hand-sewn closure[115]. In this RCT, PG was performed as described below. Interrupted 5-0 absorbable monofilament sutures were placed between the gastric mucosa and the main pancreatic duct, and interrupted sutures were placed between the wall of the pancreatic parenchyma and the gastric seromuscular layer. Additionally, an internal stenting tube was inserted for internal drainage of the pancreatic juice into the stomach. Hand-sewn closure was performed so that the main pancreatic duct was ligated and the cutting line of the remnant pancreas was closed using the fish-mouth technique. The incidence of intra-abdominal fluid collection was significantly lower in the PG group than in the hand-sewn group. However, PG did not reduce the incidence of clinical POPF and other complications compared to hand-sewn closure.Thus, the efficacy of PE has not yet been demonstrated.

However, the above two RCTs have a problem: even if the main pancreatic duct is reconstructed, small branches remain always present and may be a source of pancreatic leakage. Additionally, PE may cause the activation of pancreatic enzymes by enterokinase. Furthermore, in recent years, there has been a tendency to perform this operation with a laparoscopic procedure. It seems that adaptation should be carefully selected.

LESS INVASIVE SURGERIES

Less invasive surgeries have recently become more popular worldwide in pancreatic resection. In laparoscopic DP, a linear stapler is commonly used for stump closure of the pancreas. Therefore, the incidence of POPF from the pancreatic stump is thought to be generally similar between laparoscopic and open DP. In fact, some retrospective well-designed studies using a propensity score-matching analysis and systematic review with non-randomized trials have suggested that there was no significant difference in clinically relevant POPF although an RCT has never been conducted to examine this issue[116-120]. More recently, a robotic approach has been attempted for DP and compared with the laparoscopic approach concerning perioperative outcomes.The study demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the rate of the occurrence of POPF although spleen-preserving DP was performed more frequently in the robot-assisted approach[119-121].

Palanivelu et al[117]reported the results of an RCT comparing the laparoscopic approach for PD with the open approach. In this study, 64 of 268 patients were randomized to each group and assessed for eligibility. The results suggested that laparoscopic PD offered significant benefits in terms of hospital stay although there was no significant difference in the overall complication rates including POPF. Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses also revealed that the incidence of POPF was not significantly different between minimally invasive PD (laparoscopic and robotic PD) and open PD[122,123].

Another study using multi-institutional data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program compared pancreasspecific outcomes of minimally invasive PD (MIS-PD), including open assistance and open PD (OPD), with a focus on clinically relevant POPF[124]. In this study, 16% of patients underwent MIS-PD, of whom 15% converted to unplanned conversion. The rates of POPF were slightly greater in MIS-PD compared to OPD (15.3% vs 13.0%,respectively, Ρ = 0.03); however, MIS-PD was not an independent factor associated with POPF in the adjusted multivariable analysis. Other studies compared the rates of postoperative 30-d overall complications between laparoscopic PD and robotic PD[125,126]. This type of approach was not correlated with the overall complication rates.

The advantage of MIS-PD over open PD concerning POPF remains unclear.However, MIS-PD has a shorter exposure time in the abdominal cavity, and a smaller surgical wound than open-PD. This may reduce the potential infection during surgery. As a result, there is a possibility of reducing the occurrences of septic POPF because surgery is performed under conditions where infection is less likely to occur.Some surgeons have recently developed more suitable techniques for laparoscopic or robotic PJ[127,128], and additional experiences and the development of new devices may improve perioperative outcomes.

PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Intraperitoneal drainageDrains are frequently placed at the time of pancreatic surgery. However, adaptation and drain insertion and the time of removal have not yet been clarified. Drains allow for the evacuation of blood, pancreatic juice, bile, and lymphatic fluid. However,drains may increase the chances of retrograde infection. Moreover, there is a possibility that the indication may differ depending on whether the operation to be performed is PD or DP.

One of the issues concerning intraperitoneal drainage is the need for prophylactic intraperitoneal drainage. There was no significant difference in the incidence of POPFs in a comparison between DP with and without a drain[129-132]. However, Van Buren et al[130]and Fisher et al[131]reported that the elimination of routine intraoperative drain placement was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the length of hospital stay. In these reports, the incidence of clinical POPF tended to decrease in DP without drainage[129-132].

Two RCTs on PD with different results have been reported. In one RCT, the PANDRA trial, 395 patients were analyzed, and comparisons were made between patients with routine prophylactic intraperitoneal drains or those without drains. In the group with drains inserted, the drains were removed on the second postoperative day or later, whenever the amylase and lipase values of the drain fluid were lower than three times the serum amylase activity and there was less than 150 ml of fluid.Otherwise, the drains were not removed until the criteria were fulfilled. This trial concluded that prophylactic drainage was not necessary because clinical POPF was significantly reduced in the patients without drainage although there was no significant difference in the overall morbidity[133]. Another RCT was interrupted prematurely because the PD without prophylactic intraperitoneal drainage had a higher mortality compared to PD with drainage, although the criteria for drain removal were similar[134]. A subsequent meta-analysis reported that patients without prophylactic drainage had a significantly higher mortality despite fewer overall major complications and readmissions[135]. Patients who had a low risk of POPF may have benefits from avoiding routine intraperitoneal drainage[135]. The need for drainage after pancreatic resection continues to be controversial, particularly following PD.

Another issue is the timing of drain removal. First, the criteria for early drain removal are not defined. Kawai et al[136]reported improved outcomes with early drain removal after pancreatoduodenectomy. In this prospective cohort study, early drain removal was defined as removal on POD4 and as late as or after POD8. Adachi et al[137]demonstrated the improvement of POPF after DP with early drain removal. The authors defined early drain removal as POD1 and late removal as POD5; there was a 0% incidence of CR-POPF in the early group compared to 16% in the late removal group. However, in this study, gabexate mesilate, octreotide, and antibiotics were administered to patients with a high drain amylase level. Bassi et al[138]randomized 114 patients who underwent either PD or DP with early removal on POD3 or late removal on or after POD4. They concluded that early drain removal was associated with a decreased rate of POPF. However, in this study, Penrose drains were used, and patients whose amylase value in the drain was greater than 5000 U/mL were excluded. Although the best time to remove the drain remains unclear, prolonged placement of a drain might be a major cause of POPF because retrograde intraabdominal infection may occur[133,136,139].

Somatostatin analogsOctreotide and octreotide analogs are well known to inhibit the effects of pancreatic exocrine secretion[140], and they have been used as prophylactic agents to prevent POPF after pancreatic surgery. Therefore, the efficacy of octreotide after pancreatic surgery in the prevention of POPF was expected. Two RCTs reported the efficacy of a prophylactic somatostatin analog for the prevention of POPF following PD[141,142];however, these RCTs were reported before the definition given by ISGPF in 2005.Conversely, a recent RCT and meta-analysis evaluating somatostatin analogs did not demonstrate the reduction in the incidence of POPF after pancreatic surgery[143-151]. In particular, Nakeeb et al[152]evaluated the effect of the postoperative use of octreotide on the postoperative outcomes of PD in patients with soft pancreas and nondilated pancreatic duct. In this study, pancreatogastrostomy was used for pancreatic reconstruction. The results showed that octreotide did not affect the incidence of POPF and other complications.

Recently, the efficacy of pasireotide, which displays a broader affinity to somatostatin receptor subtypes and acts than octreotide, was noted. Allen et al[153]investigated whether pasireotide can be used to prevent POPFs in both PD and DP. In this RCT, patients received subcutaneous pasireotide or a placebo twice daily beginning preoperatively on the morning of the operation and continuing for seven days. PJ was typically performed by a duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, and pancreatic transection during DP was performed either with the use of a stapler with or without reinforcement or with hand-sewn closure. The RCT on pasireotide demonstrated the significant reduction of POPF after PD and DP. Furthermore, this drug reduced the rate of POPFs in patients who had nondilated pancreatic duct (normal pancreas).

Although there have also been reports that the use of pasireotide after pancreatic surgery does not decrease clinical POPF[154,155], a therapeutic effect by pasireotide is expected. Unfortunately, a key problem of pasireotide is cost-effectiveness because it is expensive. However, some studies have reported that pasireotide appears to be a cost-saving treatment following PD[156-158]. Indeed, the efficacy of pasireotide in reducing the incidence of POPF or other complications remains unclear, and it may be cost-effective in patients with a high risk of POPF.

CONCLUSION

POPF is still regarded as the most relevant and severe complication of pancreatic surgery, and it might develop intra-abdominal infection, hemorrhage, shock, and consequently death in some cases. Furthermore, POPF leads to increased health care costs and prolonged hospital stay. Several attempts to reduce the incidence of POPF have been made in recent years several RCTs described about methods of the reconstruction and anastomotic techniques in PD, stump closure in DP and need for stents; however, standard methods with which to minimize the incidence of POPF have not yet been established for both PD and DP. The perioperative management of POPF also remains controversial including the best time to remove the drain and the need of somatostatin analogs. Therefore, innovative attempts and further further RCTs should be performed to standardize surgical techniques and perioperative management.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Role of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- lmportance of fatigue and its measurement in chronic liver disease

- Acute kidney injury spectrum in patients with chronic liver disease:Where do we stand?

- Neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma

- Current approaches to the management of patients with cirrhotic ascites

- Pyrrolizidine alkaloids-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome: Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis,treatment, and outcomes