Postoperative complications in gastrointestinal surgery: A “hidden”basic quality indicator

2019-07-10RobertoDelaPlazaLlamasJosRamia

Roberto De la Plaza Llamas, José M Ramia

Abstract Postoperative complications represent a basic quality indicator for measuring outcomes at surgical units. At present, however, they are not systematically measured in all surgical procedures. A more accurate assessment of their impact could help to evaluate the real morbidity associated with different surgical interventions, establish measures for improvement, increase efficiency and identify benchmarking services. The Clavien-Dindo Classification is the most widely used system worldwide for assessing postoperative complications.However, the postoperative period is summarized by the most serious complication without taking into account others of lesser magnitude. Recently,two new scoring systems have emerged, the Comprehensive Complication Index and the Complication Severity Score, which include all postoperative complications and quantify them from 0 (no complications) to 100 (patient’s death), These allow the comparison of results. It is important to train surgical staff to report and classify complications and to record 90-d morbidity rates in all patients. Comparisons with other services must take into account patient comorbidities and the complexity of the particular surgical procedure. To avoid subjectivity and bias, external audits are necessary. In addition, ensuring transparency in the reporting of the results is an urgent obligation.

Key words: Morbidity; Postoperative complications; Health policy; Comprehensive Complication Index; Clavien-Dindo Classification; Complication Severity Score

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative complications represent a basic quality parameter for measuring the results of surgical procedures. Unfortunately, morbidity is not systematically recorded at surgical services. At most, certain services evaluate specific surgeries but for a limited period of time, and usually only the most serious complications are considered. As a consequence, no reliable local or international registries of morbidity are available: The only means available to the scientific community and society at large for assessing the postoperative morbidity associated with particular surgical procedures are isolated studies published by specific surgical services, which are not externally audited and often present better than average results.

Because of the lack of information on the complications associated with particular procedures or at particular units, it is impossible to carry out comparisons with other services, introduce measures for improvement, or learn from other services that obtain better results.

We are accustomed to groups of experts proposing morbidity and mortality standards for performing certain complex surgical procedures. But where do their figures come from? Are their statistics credible? Can they be considered accurate and objective when the services do not record their morbidity?

In cases in which morbidity is recorded, the reporting may be subject to a variety of biases that we will discuss in more detail later. In addition, the reports lack objective certification by an external and fundamentally impartial audit. At most surgical services, these morbidity and mortality standards are considered unattainable. Why is this so? And how can we talk about benchmarking surgical services if we do not know the morbidity associated with each surgical technique at each service, or the real situation in many of the services certified as excellent? Which services are the best, and on what criteria are these qualifications based?

At a time when society demands global transparency, it is hard to explain why this quantification is not mandatory, especially since its consequences have such an important bearing on quality of life, oncological prognosis, and healthcare costs[1,2].Here, we describe some minimum guidelines designed to allow a process of recording, communication and comparison of postoperative morbidity.

GUIDELINES FOR THE RECORDING, CLASSIFICATION AND COMPARISON OF POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

Until recently, it was difficult to quantify postoperative complications because of the lack of any standardized classifications that allowed their systematic recording and comparison.

Martin et al[3]conducted a study designed to critically evaluate the quality of surgical literature from 1975 to 2001 in the reporting of complications. They included 119 reports recording outcomes in 22530 patients[3]. Among other things, the authors observed that only 34% of the studies defined the term complication, and that the definitions varied widely (in the case of pancreatic fistula, for instance, they noted up to 12 definitions); only 20% used the degree of severity, and only 67% of the studies indicated the duration of the follow-up. Therefore, the evolution of the methodology for evaluating postoperative morbidity has been heterogeneous, and inconsistent reporting of complications has been a common feature in the surgical literature.

Despite the presence of the tools that we will outline below, in general the descriptions of the methodology used in the diagnosis, recording, and monitoring of complications are unsatisfactory: There is a systematic absence of an external and impartial audit, and so the results lack reliability.

In 2004, Dindo et al[4]published the classification of complications definitely known as the Classification of Clavien Dindo (CDC)[5], which reached a wide audience.Currently, the article has 10635 citations[6].

The CDC classifies complications in a very intuitive way and was very well received by surgeons, Nonetheless, in complex scenarios their grading may be controversial. For this reason, Clavien's group and others have provided several sets of guidelines[4,5,7-9]. The CDC considers any negative event occurring during hospitalization as a complication[4,5,10,11]. The main problem with this system is that the entire postoperative course is defined according to the most serious complication, and other minor complications are not considered - even though it has been shown that between 44% and 51.5% of patients who present morbidity at surgical services have two complications or more[9,11].

To overcome this problem, in 2013 Slankamenac et al[12]developed a new global scoring system for postoperative complications based on the CDC, called the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI). The CCI evaluates all complications separately according to the CDC; then, after entering them in the online calculator, it rates the morbidity on a scale from 0 to 100, with a score of 0 reflecting the absence of complications and a score of 100 indicating death[12]. The CCI currently has 224 citations[13]; it has been used in 104 published studies and has been discussed in two letters to the editor, two editorials and two comments in PubMed (search updated on March 18, 2019 with the strategy "Comprehensive Complication Index").

In 2015, the Complication Severity Score (CSS) became accessible online. Like the CCI, this system is also based on the CDC and has an overall score of 0 to 100[14].However, the initial publication describing the scale was rejected[14]and was only finally published in December 2018[15]. The authors claim that it improves on the CCI because the CCI assigns an inappropriately high score to a combination of complications: “…a patient who develops two Clavien-Dindo grade II complications gets a higher CCI score than a patient who develops a single Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa com-plication…”[15].The CSS is similar to the CCI in terms of its elaboration and uses a similar formula,but it assigns less weight to each grade of the CDC.

The CCI and CSS have two obvious advantages over the CDC: They take into account all the complications and produce a composite score, thus allowing the comparison of results.

In a study of all the patients operated upon at a general and digestive surgery service over a one-year period, the CDC and CCI were validated in the four groups of surgical complexity defined by the Operative Severity Score[16], in terms of the following clinical data: Hospital stay, prolongation of hospital stay, readmission and disability[11,17]. The CSS obtained similar results in this series, although the results have not yet been published[17]. The CDC showed slightly lower clinical validation values than the CCI and the CSS[17]. The CCI was the index that was least influenced by confounding factors but in one patient the score exceeded 100, while the CSS did not reach 100 in any case[17], because its numerical values are lower than those of the CCI.Thus, the use of CSS would theoretically have an advantage in highly complex surgeries with a multitude of complications which, in exceptional cases, might produce a higher CCI.

Several studies have shown the relationship between increased costs and higher CDC scores[2,18-21]. Only two teams have studied the relationship of the CCI with postoperative costs. Staiger et al[22]reported (among other findings) a strong correlation between the CCI and costs three months post-surgery, and higher correlations for more complex procedures. They also developed a cost prediction tool.De la Plaza et al[2]studied the postoperative costs in patients operated over a one-year period at a general surgery and digestive service, finding a moderate to strong correlation of the CCI with overall postoperative costs, which increased with the surgical complexity according to the Operative Severity Score. In all the groups, this correlation was higher in emergency surgery. In addition, the CCI was correlated with postoperative costs in patients with prolonged postoperative stay and in those without, and also with the initial operating room costs[2]. This relationship between postoperative costs and the CCI provides further support for the score’s clinical validity.

Comparing the two new systems, we believe that the CCI should be preferred to the CSS for the following reasons: (1) The preparation of the CCI involved 227 patients and 245 physicians (surgeons, anesthetists and intensivists)[12]. In the preparation of the CSS, only 49 senior gastrointestinal and hepato-pancreatico-biliary surgeons in India were included (“senior” being defined as having at least 5 years of experience after graduating), and no patients[15,23]; and (2) The CCI has a greater diffusion worldwide[13].

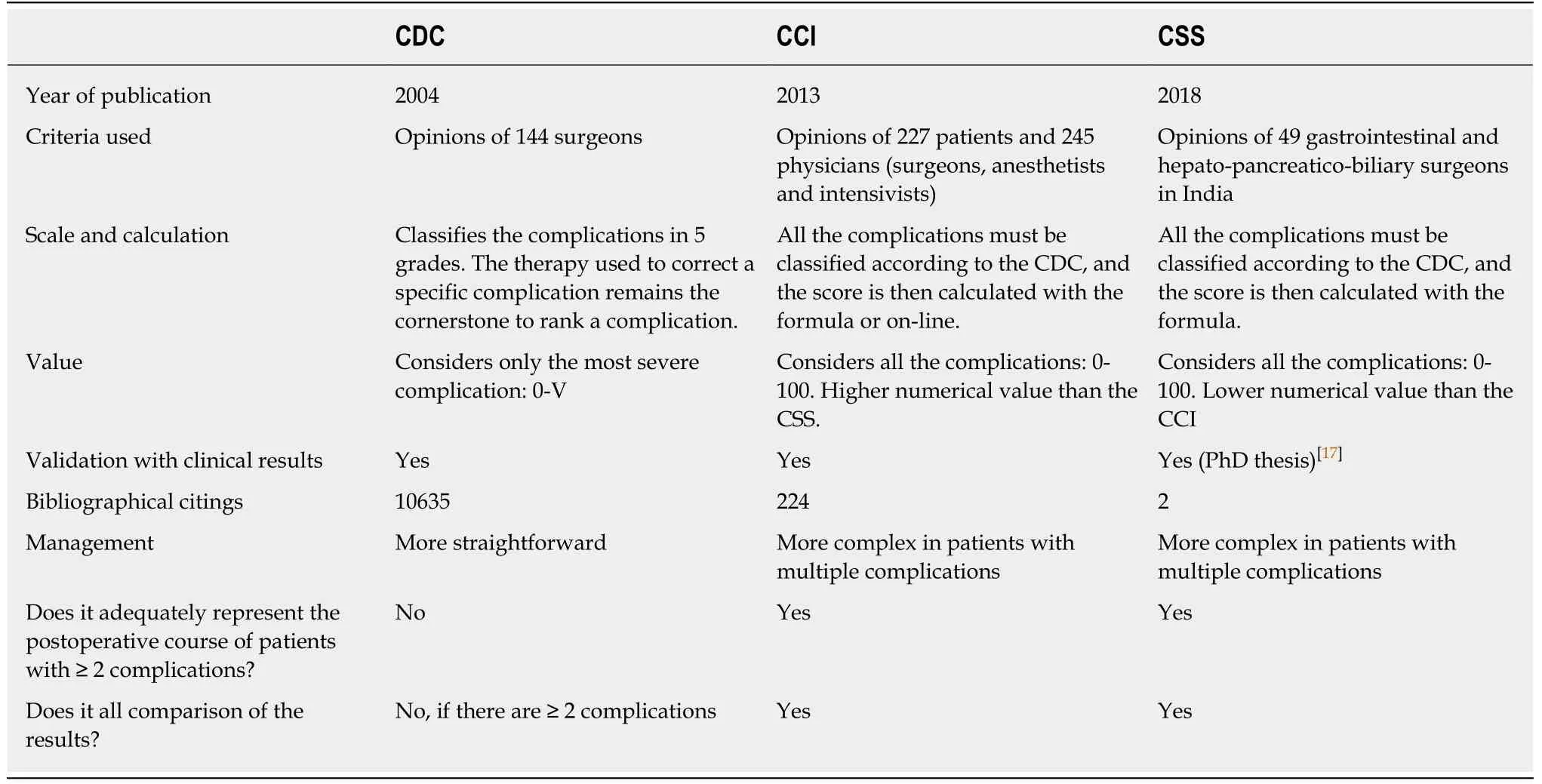

A summary of these three tools (CDC, CCI and CSS) is shown in Table 1.

Therefore, the CDC is the most suitable classification for each individual postoperative complication, while the CCI is able to numerically quantify the postoperative complications in a particular patient or group of patients undergoing a surgical procedure. In addition, the percentage of certain important complications is also specified for each surgical procedure: For example, in esophagectomies, gastrectomies, pancreatectomies, colectomies, and so on, the presence of specific and important complications such as the presence of anastomosis and pancreatic fistulas is recorded. In any case, the mere fact of initially classifying each complication according to the CDC would alert surgical departments to less important complications that are relatively easy to improve, such as infection of the surgical wound,urinary tract infection, central venous catheter, or pulmonary complications.

Complications should be recorded for at least 90 d post-surgery, as should readmissions in that period. Between 30 and 90 d postoperatively the number of complications rises by 11.6%[17]. The recording of complications that occur outside the hospital environment is a more difficult issue. These complications are less serious,but it is important to evaluate them (for example, complications after less complex procedures such as cholecystectomy). This problem could be minimized by the use of an electronic medical recording system that incorporates the care carried out outside the hospital.

It is essential to report complications as they occur, or at least when evidence of the event becomes available. The event should be recorded in the patient progress notes or in specially designed forms in which the complication and the treatment are reported in writing and the CDC. Consultation of nurses' notes is also fundamental.

Within 90 d of the procedure, a summary of the morbidity in each patient should be made by the physicians at the service based on the clinical history, and should be stored in (for example) an Excel table recording each complication, the CDC, and the CCI[11]. In our experience, the average time taken to evaluate complications at 90 d post-surgery and to record them in the spreadsheet ranges between 5 and 10 min per patient.

To compare the results at different services, one must take into account the complexity of the patient’s condition, not just on the basis of the ASA but by making a risk adjustment with complexity or severity scores such as the Charlson Comorbidity scale[24]. It is also important to compare surgical procedures of similar complexity and technical difficulty[2]. An impartial external audit is essential. When used by physicians at our service to record morbidity and applying the methodology described above, the CDC and CCI presented accuracy rates of 88% and 81%;however, when only patients with complications were included, the rates fell respectively to 69% and 49%[17,25].

There are several explanations for the fact that postoperative complications are only rarely quantified. The most important, in our view, is the fact that the better the recording system, the worse the results. Surgeons may regard complications as an indication of personal failure, and fear comparison with other services because the results may reflect badly on their work. Furthermore, at a time when centres of reference are being established for complex surgical procedures such as esophagectomy, gastrectomy, pancreatectomy or hepatectomy, high morbidity rates at particular services might disqualify them from operating on these patients.

It is hard to understand why public authorities choose these services of reference only on the basis of volume (or sometimes for political reasons) and fail to take actual audited results into account, such as morbidity and disease-free survival in cancer patients. Besides questions of cost-effectiveness, ensuring the optimal use of the means available is an obligation in a system with limited resources.

Another common bias is the failure to record certain minor complications. For example, the CDC includes nausea, poorly controlled pain and atelectasis as complications, which in practice may go unreported. The inclusion of minor complications may magnify the actual morbidity, but it eliminates subjective interpretations and makes them the same for all auditors. The presence of errors in the classification of complications according to the CDC, particularly in complex scenarios, should also be borne in mind. However, many useful clarifications have already been made in this regard[4,5,7-9].

CONCLUSION

Little is known at present about real postoperative morbidity.

In the recording of postoperative complications, the following points must be taken into account: (1) A complication should be considered as any negative event occurring in a patient during hospitalization[4,5,10,11]; (2) Physicians and nurses must be made aware of the need to record complications; (3) Training with the CDC must be provided, especially in order to deal with complex scenarios; (4) Exhaustive, external impartial recording of all complications must be performed. However, biases cannot be totally avoided since the registry is performed by doctors and nurses at the service under evaluation; (5) Complications should be recorded on a form specially created for the purpose; (6) Physicians’ and nurses’ notes should be consulted; and (7) An external audit must be carried out by experts without any conflict of interest with regard to the surgery service or its members so as to avoid deficiencies in the recording and classification and other biases.

Table 1 Comparison of the characteristics of the clavien dindo classification, the comprehensive complication index and the complication severity score

The recording of the complications deriving from all surgical procedures is an urgent scientific and social obligation. Transparency in the reporting is also mandatory. There are sufficient means available now to record complications accurately and efficiently, with only minimal investment and the results are available in the short-medium term. Policy-makers in the field of health administration should not let this opportunity pass.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Modified FOLFlRlNOX for resected pancreatic cancer: Opportunities and challenges

- Role of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms and functions in development of ulcerative colitis

- Role of epigenetics in transformation of inflammation into colorectal cancer

- The role of endoscopy in the management of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome

- Predicting systemic spread in early colorectal cancer: Can we do better?

- NlMA related kinase 2 promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation via ERK/MAPK signaling