Role of epigenetics in transformation of inflammation into colorectal cancer

2019-07-10ZhenHuaYangYanQiDangGuangJi

Zhen-Hua Yang, Yan-Qi Dang, Guang Ji

Abstract Molecular mechanisms associated with inflammation-promoted tumorigenesis have become an important topic in cancer research. Various abnormal epigenetic changes, including DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin remodeling, and noncoding RNA regulation, occur during the transformation of chronic inflammation into colorectal cancer (CRC). These changes not only accelerate transformation but also lead to cancer progression and metastasis by activating carcinogenic signaling pathways. The NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways play a particularly important role in the transformation of inflammation into CRC, and both are critical to cellular signal transduction and constantly activated in cancer by various abnormal changes including epigenetics. The NF-κB and STAT3 signals contribute to the microenvironment for tumorigenesis through secretion of a large number of pro-inflammatory cytokines and their crosstalk in the nucleus makes it even more difficult to treat CRC. Compared with gene mutation that is irreversible, epigenetic inheritance is reversible or can be altered by the intervention. Therefore, understanding the role of epigenetic inheritance in the inflammation-cancer transformation may elucidate the pathogenesis of CRC and promote the development of innovative drugs targeting transformation to prevent and treat this malignancy. This review summarizes the literature on the roles of epigenetic mechanisms in the occurrence and development of inflammation-induced CRC. Exploring the role of epigenetics in the transformation of inflammation into CRC may help stimulate futures studies on the role of molecular therapy in CRC.

Key words: Colorectal cancer; Inflammation; DNA methylation; Histone modification;LncRNA; MicroRNAs; Epigenetics Vetvicka V, Zheng YW S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Ma YJ

INTRODUTION

In recent years, accumulating evidence indicates that chronic inflammation leads to the occurrence and development of many tumors[1,2]. The relationship between inflammation and cancer has long been investigated. Two thousand years ago, the Greek physician Galen described the similarities between cancer and inflammation and believed that cancer might evolve from inflammatory lesions[3]. In 1863, Virchow identified inflammatory cell infiltration in tumor tissues and explained it as a reaction to the origination of cancer at sites of chronic inflammation, proposing the hypothesis of the inflammation-cancer transformation[4]. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignant tumor and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[5]. The pathogenesis of CRC is complex. Previously, most scholars believed that CRC was a genopathy and a highly heterogeneous tumor resulting from an accumulation of genetic abnormalities, the failure of cancer defense mechanisms, and the activation of carcinogenic pathways[6]. However, increasing evidence suggests that CRC is a typical inflammation-dependent cancer. The risk of developing CRC increases in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease, which is more likely to be caused by chronic inflammation of the intestinal mucosa than by any definitive genetic predisposition[7-9]. In addition, chronic inflammation plays an important role in the occurrence and development of sporadic CRC, and the expression of interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-17A, and IL-23 is increased in most sporadic CRC cases[10,11].

Various proinflammatory signaling pathways participate in the transformation of inflammation into CRC, including the NF-κB, IL-6/STAT3, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)/PGE2, and IL-23/Th17 pathways, which induce the production of inflammatory mediators, upregulate the expression of antiapoptotic genes, stimulate cell proliferation and angiogenesis, and thereby contribute to tumorigenesis[12]. The NF-κB signaling pathway includes both classical and non-canonical pathways. The classical pathway is activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, pathogen-associated or damageassociated molecular patterns. The non-canonical pathway is activated by a small subset of cytokines including lymphotoxin, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand, CD40 ligand, and B cell activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family[13].Activation of NF-κB not only affects DNA damage and carcinogenic mutations, but also causes tumorigenesis by promoting the production of reactive oxygen species(ROS) and reactive nitrogen. It can also cause chromosomal instability, aneuploidy,and epigenetic changes, leading to tumorigenesis and development[14,15]. NF-κB and STAT3 are nuclear transcription factors required for the regulation of tumor proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, and invasion; their target genes encode the critical cancer-promoting inflammatory mediators[13-19]. NF-κB and STAT3 signaling contributes to the tumorigenic microenvironment by mediating the secretion of various proinflammatory cytokines, and the crosstalk of these pathways in the nucleus makes CRC even more difficult to treat[18,20,21].

To date, abundant evidence has indicated that epigenetic changes play an important role in the transformation of inflammation into CRC as well as in the occurrence, development, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance of this cancer.

These epigenetic changes include DNA methylation, histone modification, and noncoding RNA (ncRNA) alterations. Molecular mechanisms associated with inflammation-promoted tumorigenesis are currently an important branch of cancer research; therefore, understanding the role of epigenetic inheritance in the occurrence and development of CRC may elucidate the pathogenesis of this cancer and promote the development of innovative drugs targeting transformation for CRC treatment.

DNA METHYLATION

DNA methylation is an important epigenetic modification related to gene expression and mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), and an imbalance in genomic methylation leads to tumors. Approximately half of human gene promoters are rich in C-G sequences, also called CpG loci because of the phosphodiester bond linking the C and G nucleotides. If they are present in DNA sequences, CpG islands are likely located in genetic regulatory elements[22,23]and are usually defined as regions with a length greater than 200 base pairs and a G + C content greater than 50%[24,25]. DNA methylation starts at one end of the islands and continues to gene promoters and initiation sites, altering the three-dimensional configuration of the DNA and inhibiting its interaction with transcription factors, ultimately silencing gene expression. In contrast, hypomethylation promotes gene expression[23,26]. In CRC, the commonly observed types of methylation include hypermethylation of antioncogene DNA and hypomethylation of oncogene DNA. More importantly, DNA methylation can be stably inherited by progeny cells through histone marks at methylation sites,leading to hereditary effects without changes in DNA sequences[27].

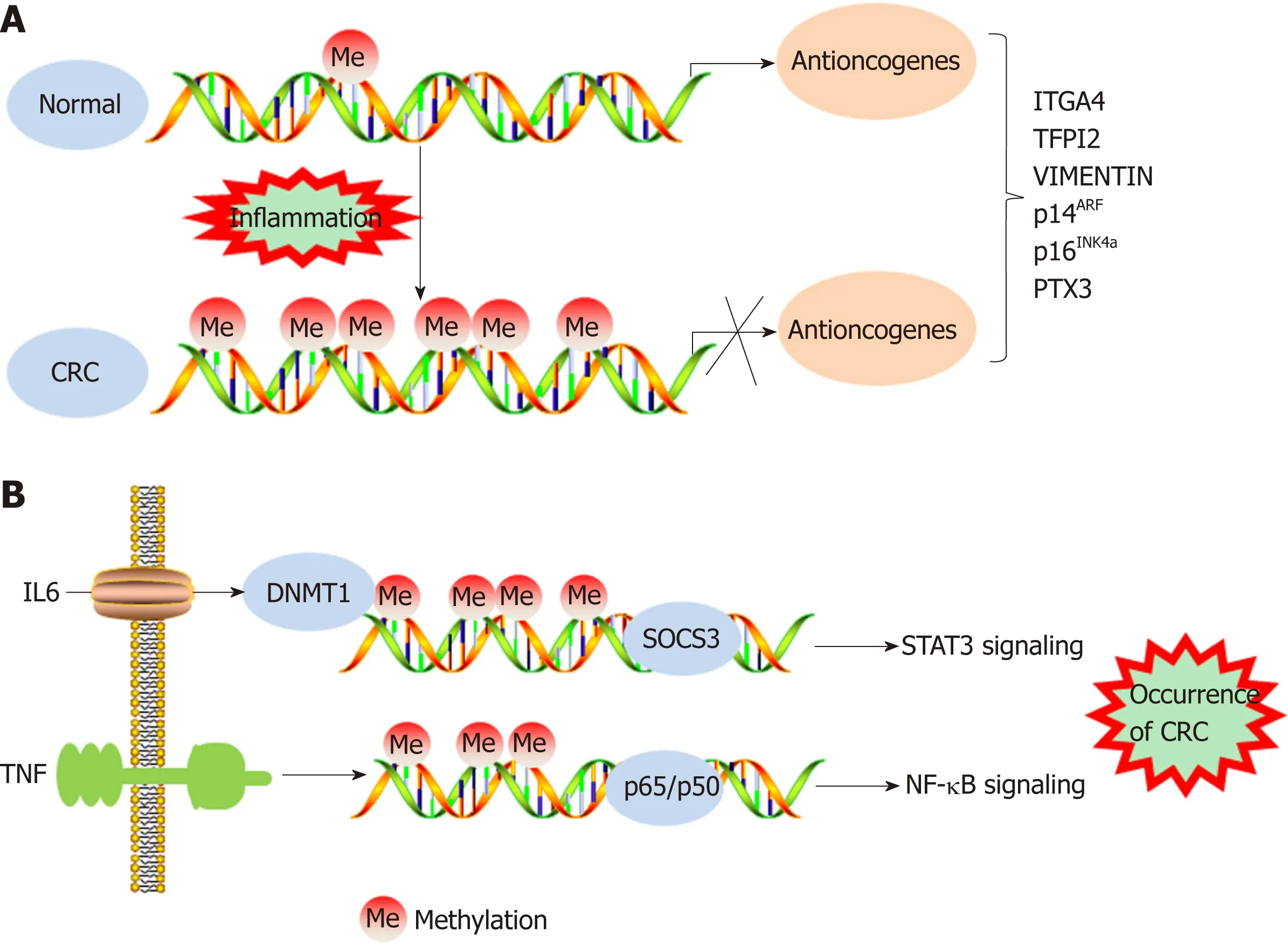

IBD has been demonstrated to increase the risk of CRC incidence. A meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies indicated that the incidence of CRC within 10, 20,and > 20 years was 1%, 2%, and 5%, respectively, in patients with IBD[28,29]. In addition,DNA methylation promotes the tumorigenesis and progression of colitis-associated CRC (CAC). The expression of DNMT1 is appreciably higher in CAC samples than in tumor tissues of patients with sporadic CRC, indicating an increased level of DNA methylation in CAC tissues[30]. However, the frequency of chromosomal instability and microsatellite instability in CAC is generally the same as that in sporadic CRC. In approximately 46% of patients with microsatellite instability-high CAC, the hMLH1 gene is hypermethylated[31]. The cell cycle inhibitor gene p16INK4a, which has been reported to be negatively associated with the occurrence of sporadic CRC, is often methylated in tumor samples from CAC patients[32,33]. In addition, the p14ARFgene can indirectly regulate the expression of the p53 protein, and methylation of p14ARFis a relatively common early event in ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal carcinogenesis[34]. Furthermore, the methylation levels of the ITGA4, TFPI2, and VIM gene promoters are increased in inflamed colon tissues, which may imply a high risk of CAC development[35](Figure 1A). Recent genome-wide studies have provided important insights into the characteristics of DNA methylation in tumors[36]. Using monoalkyl methylation profiles in a colitis-induced mouse colon cancer model, Abu-Remaileh et al[37]identified a novel epigenetic modification characterized by hypermethylation of the DNA methylation valley (DMV), which leads to the silencing of DMV-related genes, thus facilitating inflammation-induced cell transformation.

Studies have shown that the methylation of specific genes is associated with inflammatory conditions, dysplasia, and malignant transformation, indicating that epigenetic modifications are involved in inflammation-induced carcinogenesis[38-40].Many proinflammatory cytokines secreted as a result of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathway activation are activated and promote the transformation of inflammation into CRC[20]. For example, IL-6 silences the expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS 3) by inducing high expression levels of DNMT1. SOCS3 is an important negative regulator of cytokine-induced STAT3 signaling, and its silencing ultimately contributes to the occurrence of CRC[41]. TNF molecules depend on the NFκB signaling pathway to silence the gene encoding the proapoptotic protein kinase cδbinding protein through gene promoter methylation, which facilitates the growth of cancer cells[42]. IL-6 has been demonstrated to increase the methylation of the promoter regions of genes related to tumor inhibition, cell adhesion, and apoptosis resistance,and this increase could be prevented by treatment with the DNMT 1 inhibitor 5-azadeoxycytidine[30](Figure 1B). IL-6 produced during intestinal inflammation can modulate the expression of CYP2E1 and CYP1B1 (cytochrome P450 enzymes) via transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms, altering the metabolic capability of epithelial cells. Indeed, one study suggested that IL-6 reduces the expression of miR27b, which targets CYP1B1, through a DNA methylation mechanism, thereby increasing dietary carcinogen activation and DNA injury, which leads to the occurrence of CRC[43]. As an important component of natural humoral immunity,PTX3 activates and regulates the complement cascade by interacting with C1q and factor H and plays a role in the regulation of inflammation. PTX3 has been considered an exogenous antioncogene, and PTX3 deficiency increases sensitivity to epithelial carcinogenesis[44,45]. An analysis of epigenomic data revealed high methylation levels in the PTX3 gene promoter in CRC[46,47]. Prostaglandin, a signaling molecule with important pro- and anti-inflammatory effects, is synthesized from arachidonic acid through the prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase (PTGS; also called cyclooxygenase or COX) pathway. PTGS2 (also called COX-2), one of the key enzymes in the pathway,is overexpressed in CRC, leading to oversecretion of the downstream metabolite prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2)[48]. Deregulation of the COX-2/PGE2signaling pathway is associated with many tumors, including CRC, and the expression levels of COX-2 and PGE2are closely related not only to metastasis and poor prognosis in patients with CRC but also to chemotherapeutic resistance in tumors[49-52]. Indeed, a study showed that high methylation rates of select gene promoters stimulate the production of PGE2,block the production of other bioactive prostaglandins, and ultimately promote the development of CRC[53]. Moreover, the results of this study suggest that the antitumor effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be related to the ability of these drugs to inhibit COX-2. FXR regulates bile acid metabolism and inhibits the production of the secondary bile acid cholic acid; therefore, FXR performs anticancer functions. In CRC, the expression of FXR is negatively associated with the degree of tumor malignancy and with poor clinical outcomes[54,55]. The APC gene is typically mutationally inactivated in the pathogenesis of CRC[56]. Loss of function of APC silences FXR expression through CpG methylation in mouse colonic mucosa and human colon cells, decreasing the expression of downstream bile acid-binding proteins and heterodimers and increasing the expression of related genes (COX-2 and c-MYC) in inflammation and CRC[57]. Recent studies demonstrated that vitamin D(VD) deficiency is associated with the occurrence of CRC. VD, an anti-inflammatory agent, regulates adipocytes and their functions via the VD receptor (VDR), resulting in decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines[58-61]. Using blood and visceral adipose tissues collected from CRC patients and healthy controls, Castellano-Castillo et al[62]explored the relationship among the levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D[25(OH)D], expression of the VDR gene in adipose tissue, levels of proinflammatory markers, expression of the epigenetic factor DNMT3A, and methylation of the VDR promoter. These results suggest that adipose tissue may be a critical factor in the occurrence of CRC and that low expression levels of 25(OH)D and high expression levels of VDR may partially mediate this relationship by modulating DNA methylation and promoting inflammation[62]. In addition, inflammatory mediators such as ROS and reactive nitrogen species may lead to genomic instability, which contributes to carcinogenesis via the mutation of protooncogenes and tumor suppressor genes[63]. Vitamin C (VC) and vitamin E (VE) are antioxidants that can scavenge free radicals[64,65]. One study suggests that VE antagonizes high glucoseinduced oxidative stress, exhibiting beneficial effects on gene promoter methylation and gene expression in the CRC cell line Caco-2[66]. In addition, the results of an in vitro experiment indicated that VC could enhance antitumor drug-induced DNA hydroxymethylation and reactivate epigenetically silenced expression of the tumor suppressor CDKN1A in CRC cells[67]. Therefore, supplementation with related vitamins may be an alternative approach to treat CRC. Moreover, black raspberry(BRB) anthocyanins, which can modulate changes in inflammation and SFRP2 gene methylation, have been reported as agents for CRC prevention[68]. In summary, DNA methylation facilitates the transformation of inflammation into CRC in both the local environment of intestinal inflammation and systemic inflammation.

Figure 1 DNA methylation regulates the transformation of inflammation into colorectal cancer. A: DNA hypermethylation levels inhibit expression of antioncogenes, resulting in the occurrence of colorectal cancer (CRC); B: Inflammatory cytokines regulate STAT3/NF-κB signaling to promote the occurrence of CRC by DNA methylation. CRC: Colorectal cancer; IL-6: Interleukin-6; DNMT1: DNA methyltransferase 1; SOCS3: Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3.

HISTONE MODIFICATION

Chromatin is a macromolecular complex composed of DNA, RNA, and proteins.Histones, which regulate DNA strand compaction and gene expression, are the main protein component of chromatin[23]. The core histones are composed of four major families-H2A, H2B, H3, and H4[69]. The nucleosome is a chromatin unit consisting of 150 to 200 base pairs of DNA wrapped closely around a cylindrical histone core.Posttranslational covalent modification of the histone tail constitutes an epigenetic mechanism that regulates chromatin structure and gene expression in human cancers.Histone tail modifications include phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation,ubiquitination, glycosylation, deamination, and ribosylation[70,71]. Various modifications alter the three-dimensional structure of nucleosomes and affect the transcriptional control of related genes by inducing either an “inactive” tight heterochromatin or an “active” open euchromatin conformation. Insight into histone modification is not as deep as that into DNA methylation; the only well-studied histone modifications are the acetylation/deacetylation and methylation/demethylation of lysine and arginine residues in the histone tail[72,73]. These bivalent histone modifications are mediated by polycomb group proteins (transcriptional repressors), which contribute to silencing a specific set of anti-oncogenes in human cancers. Polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs) include PRC1 and PRC2, which silence genes alone or in cooperation[74,75].

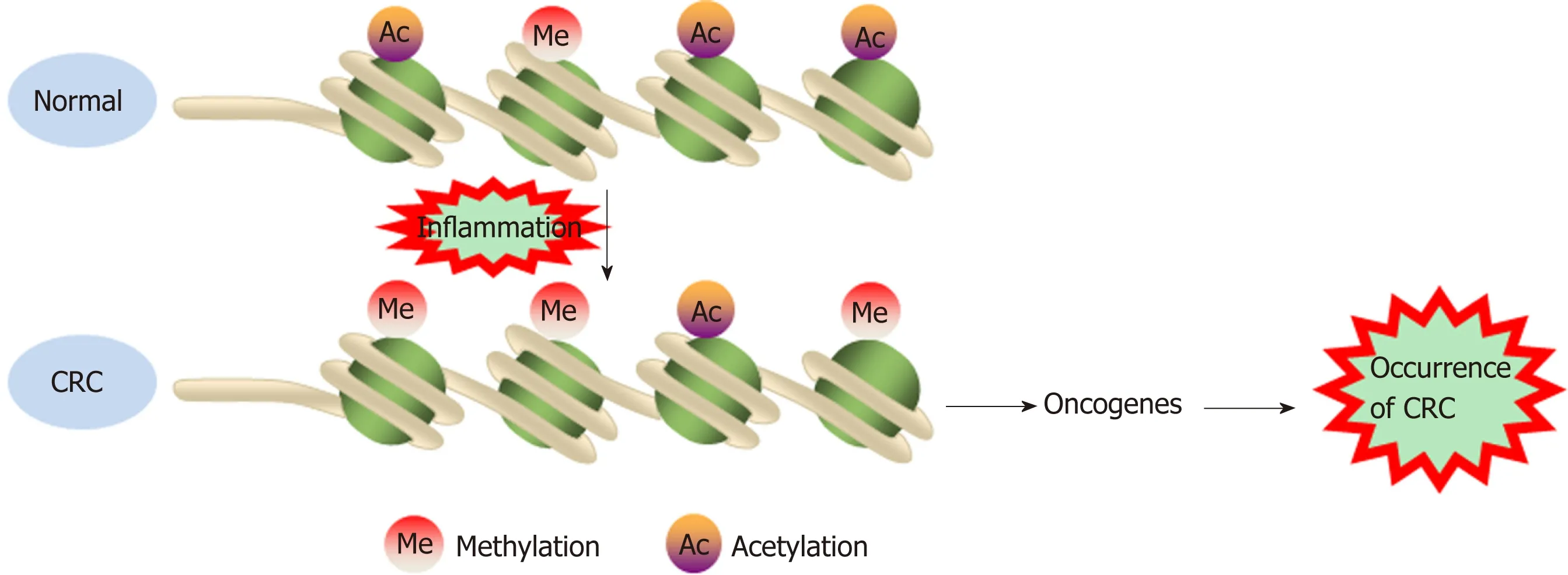

Histone modification abnormalities arise during the transformation of inflammation into CRC. Profiles for active enhancers using H3K27ac histone modification identified several cancer markers, such as the LYZ, S100P, and NPSR1 proteins, which were elevated in CAC[76]. In a mouse model, deletion of the Giα2 protein led to spontaneous colitis and right multifocal CRC, which is similar to human CRC with defective mismatch repair. Moreover, MLH1 and PMS2 expression are reduced in the colonic epithelium of Giα2-/-mice after the onset of hypoxic colitis.Notably, MLH1 is epigenetically silenced by reduced histone acetylation. These data connect chronic hypoxic inflammation, histone modulation, and CRC development[77].

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway exerts either pro- or anti-inflammatory functions by activating or inhibiting NF-κB signals, respectively, playing an important role in the occurrence and development of CRC[78]. DACT3, the negative regulator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, is transcriptionally suppressed in CRC in a manner related to bivalent histone modification. However, DACT3 expression can be restored after combined administration of drugs targeting histone methylation and deacetylation, resulting in strong inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signal transduction and massive CRC cell apoptosis. Therefore, DACT3 may be an important factor in the treatment of CRC through epigenetic mechanisms[79]. EZH2, a catalytic subunit of PRC2, is essential for maintaining the integrity and homeostasis of the epithelial cell barrier in inflammatory states. EZH2 expression is downregulated in IBD patients,and EZH2 inactivation in the intestinal epithelium increases the sensitivity of mice to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)- and 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced experimental colitis. One study indicated that EZH2 deficiency could stimulate the expression of TRAF2/5 and enhance the NF-κB signaling induced by TNF-α, which led to an uncontrolled inflammatory reaction and ultimately contributed to tumorigenesis[80]. Researchers identified a new epigenetic mechanism underlying the preventive effects of aspirin in CAC. Aspirin reduced the activity of histone deacetylases and fully restored H3K27ac. Moreover, aspirin depressed azoxymethane/DSS-induced H3K27ac accumulation in the promoters of the inducible nitric oxide synthase, TNF-α, and IL-6 genes and suppressed the production of proinflammatory cytokines, playing a role in the prevention of cancer[81](Figure 2).Although few studies have investigated the role of histone modification in the transformation of inflammation into CRC, notably, histone modification may interact with DNA methylation to induce epigenetic silencing and promote tumorigenesis.

MICRORNAS

Most of the human genome is transcribed into RNAs, which are classified as RNAs with coding potential or RNAs without. The latter RNAs are also called ncRNAs.NcRNAs were historically considered “transcriptional waste”, but accumulating evidence indicates that ncRNAs strongly impact many molecular mechanisms[82].MicroRNAs are single-stranded ncRNAs with a length of 20 nucleotides that function primarily to negatively regulate gene expression by binding to target RNAs and inducing the degradation or inhibiting the translation of those RNAs[83].

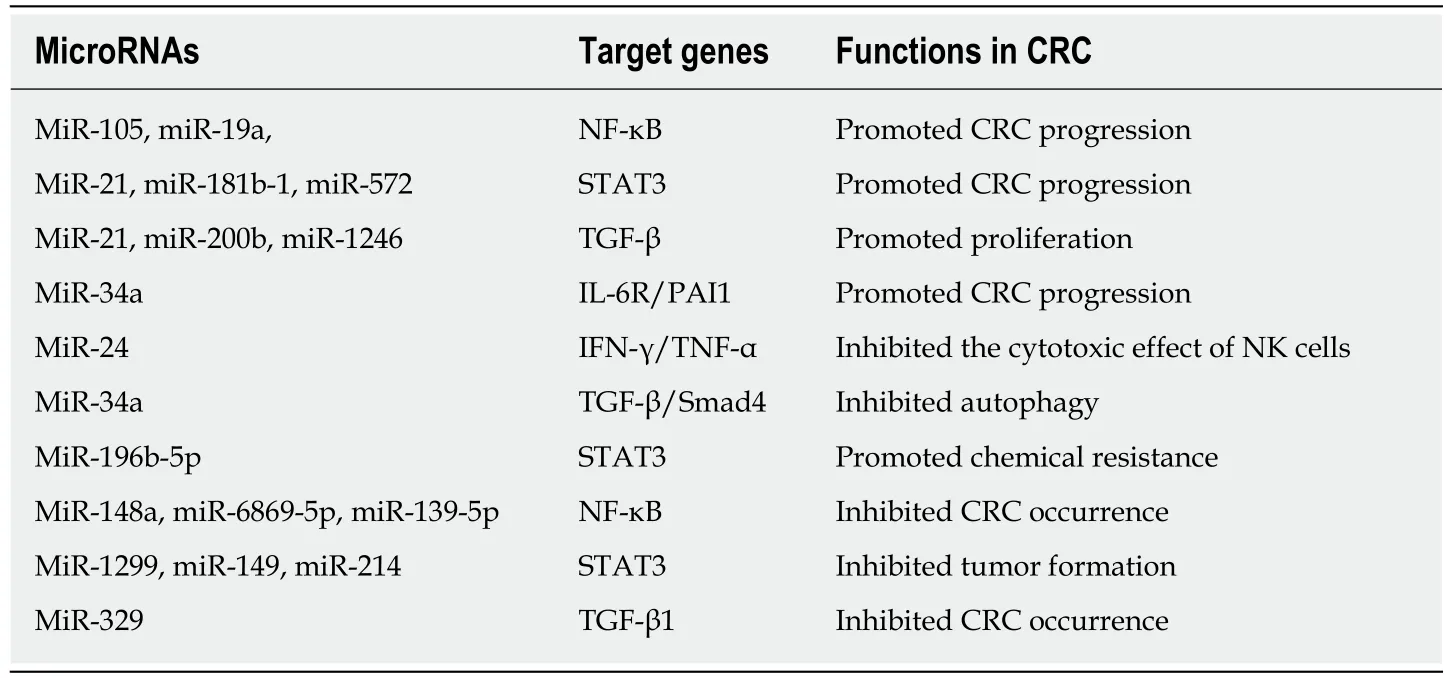

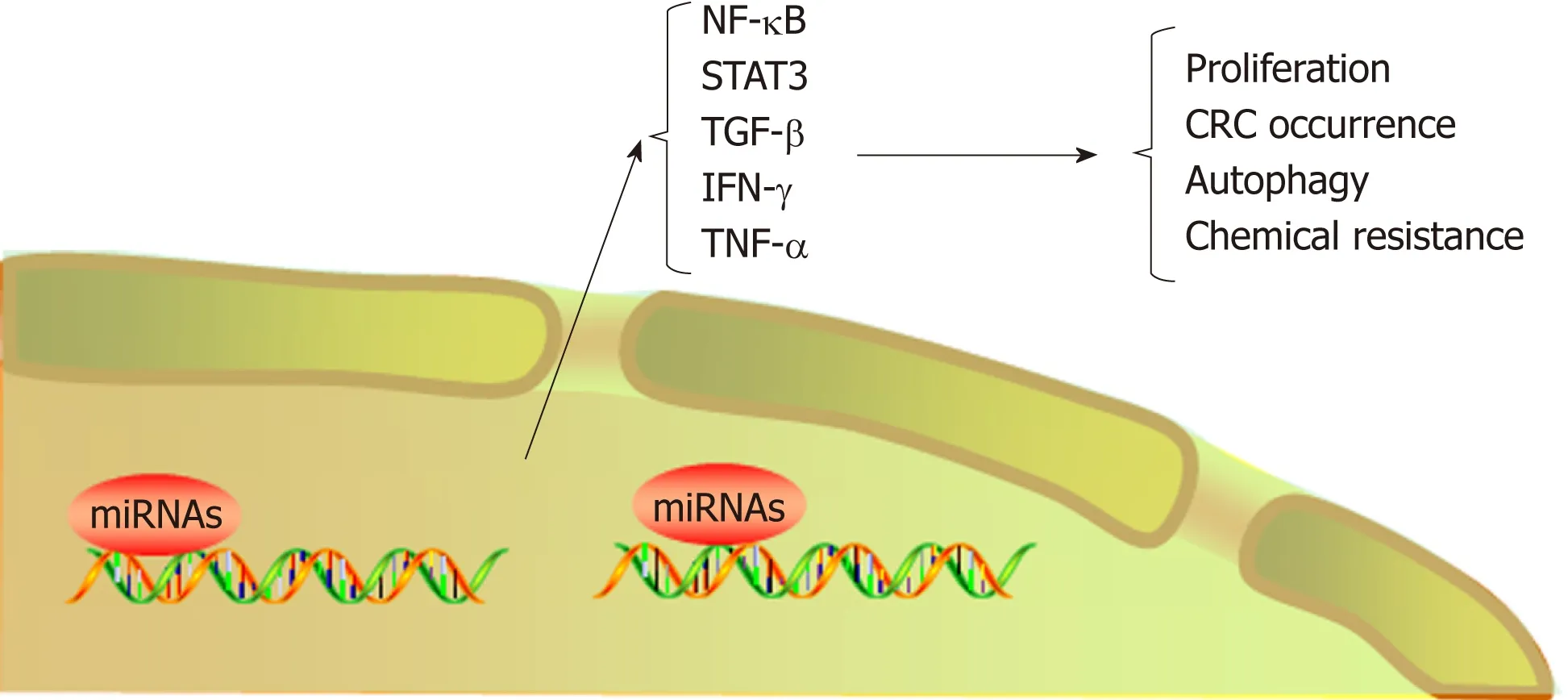

The NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways play an important role in the transformation of inflammation into cancer[13], and numerous microRNAs promote transformation by participating in these signaling pathways. Slattery et al[84]analyzed the expression profiles of genes and associated microRNAs in the NF-κB signaling pathway between CRC and normal mucosa, providing new insight into therapeutic targets for CRC. TNF-α has been shown to increase the expression of miR-105, which targets RAP2C, activate NF-κB signal transduction by IKK, and ultimately contribute to CRC progression[85]. Another study demonstrated that TNF-α leads to high expression of miR-19a, which can also activate NF-κB signaling to facilitate the occurrence of colitis and CAC[86]. STAT3 not only is a downstream target of IL-6 but also interacts with miR-21, miR-181b-1, PTEN, and CYLD, which implicates the epigenetic switch that links inflammation to cancer[87]. In addition, by activating miR-21, NR2F2 inhibits Smad7 expression and promotes TGF-β-dependent epithelialmesenchymal transition (EMT) in CRC[88]. In primary CRC samples and cell lines,increased STAT3 expression levels are accompanied by elevated miR-572 and decreased MOAP-1 levels, and miR-572 has been found to reduce the expression of the proapoptotic protein MOAP-1 and to contribute to CRC progression[89]. Öner et al[90]demonstrated that combined inactivation of TP53 and miR-34a promotes CRC metastasis by elevating the levels of IL-6R and PAI1, implying that modifying these processes might be alternative approaches to treat CRC. Immune cells play a dual role in the occurrence and development of CRC, and natural killer (NK) cells promote tumor cell apoptosis by secreting high levels of cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF-α[91].

The level of miR-24 was reported to be increased in NK cells from CRC patients, a characteristic that decreased the levels of cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α, by suppressing Paxillin expression and inhibiting the cytotoxic effect of NK cells on CRC cells[92].

MicroRNAs not only promote the transformation of inflammation into CRC but also lead to chemotherapeutic resistance. For example, in CRC patients treated with oxaliplatin, miR-34a expression decreased significantly but Smad4 and TGF-β expression increased. In addition, the expression levels of Smad4 and miR-34a were negatively correlated in CRC patients. Further investigation demonstrated that miR-34a targeted Smad4 through the TGF-β/Smad4 pathway and ultimately inhibited cellular autophagy[93]. Ren et al found overexpression of miR-196b-5p in recurrent CRC tissues, which was associated with a poor prognosis. Further investigation showed that miR-196b-5p activated STAT3 signaling and promoted the chemical resistance of CRC cells to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) by targeting the negative regulators SOCS1 and SOCS3 in the STAT3 signaling pathway[94]. Clarification of the role of microRNAs in CRC resistance mechanisms can improve the efficacy of chemotherapy by targeting the corresponding microRNAs. Indeed, microRNAs overexpressed during the transformation of inflammation into CRC are often associated with disease progression. In addition, certain microRNAs are silenced or downregulated during the occurrence and development of CRC; these microRNAs generally inhibit the transformation of inflammation into cancer. For instance, miR-148a, miR-6869-5p, and miR-139-5p inhibit transformation by suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway[95-97];miR-1299, miR-149, and miR-214 inhibit tumor formation by suppressing the STAT3 signaling pathway[98-100]; and miR-329 inhibits CRC occurrence by targeting TGF-β1[101].MiR15A and miR16-1, which might act as tumor suppressors, were found to be downregulated in CRC[102]. Animal experiments showed that deficiency of miR15A and miR16-1 led to an accumulation of immunosuppressive IgA+B cells in intestinal cancer tissues, thereby inhibiting the proliferation and functions of CD8+T cells with antitumor immunity and ultimately promoting tumor progression[103].

Figure 2 Histone methylation and acetylation modifications increase oncogene expression to promote cancer occurrence. CRC: Colorectal cancer.

Exosomal microRNAs

Exosomes are small vesicles released by cells into the extracellular environment.These vesicles transmit information to adjacent or distant cells by transferring RNAs and proteins, thus affecting signaling pathways in various physiological and pathological conditions[104,105]. Recently, microRNAs enriched in exosomes have been found to interact with immune cells and proinflammatory cytokines and to participate in the progression and metastasis of CRC. For example, exosome-mediated miR-200b was indicated to promote the proliferation of CRC cells upon TGF-β1 exposure[106]. In addition, it was reported that the level of miR-10b was significantly higher in exosomes derived from CRC cells than in those derived from normal colorectal epithelial cells and that CRC-derived exosomes could promote CRC progression[107].Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), a biomarker of solid tumors, are usually associated with a poor prognosis. A recent study has shown that CRC cells carrying mutant p53 genes selectively shed miR-1246-enriched exosomes. These exosomes can be captured by neighboring TAMs, which then secrete numerous proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, TGF-β, and MMPs, to promote the immune suppression,invasion, and metastasis of CRC cells[108](Figure 3, Table 1).

LNCRNAS

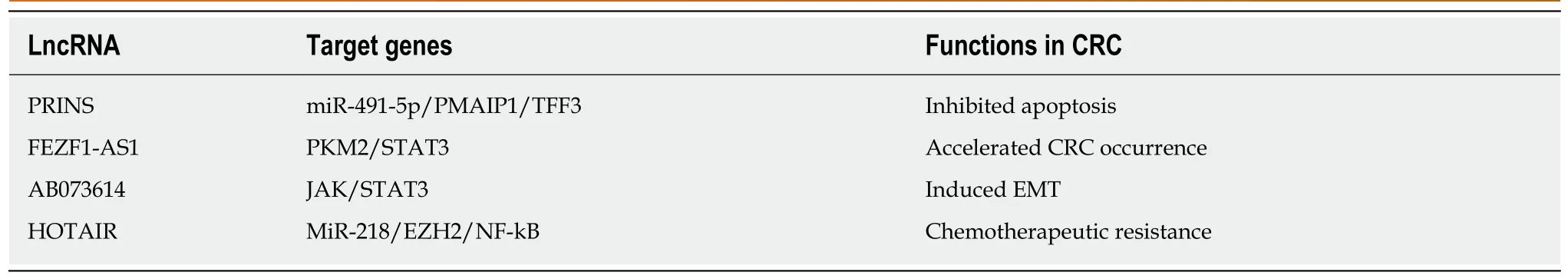

LncRNAs refer to noncoding transcripts of more than 200 nucleotides[109]. LncRNAs are important participants in cancer biology and generally cause the abnormal expression of gene products, leading to the progression of various human tumors[110,111]. In addition, lncRNAs are involved in the transformation of chronic inflammation into CRC. For example, a study indicated that the interaction between lncRNA PRINS and miR-491-5p regulated the proapoptotic factor PMAIP1 and enhanced the antiapoptotic effect of TFF3 against the proapoptotic effects of IFN-γ and TNF-α in CRC cells[112]. LncRNA FEZF1-AS1 expression was higher in CRC tissue than in normal tissue and was associated with a poor prognosis in CRC. FEZF1-AS1 can bind to and increase the stability of the pyruvate kinase 2 (PKM2) protein, which can increase PKM2 levels in the cytoplasm and nucleus and promote pyruvate kinase activity and lactic acid production. Upregulation of nuclear PKM2 induced by FEZF1-AS1 was found to further activate STAT3 signal transduction and accelerate the transformation of inflammation to cancer[113]. In addition, researchers found that lncRNA AB073614 induced EMT in CRC cells by regulating the JAK/STAT3 pathway[114]. Recent studies have shown that lncRNAs not only participate in the transformation of inflammation to tumors but also induce the resistance of CRC to chemotherapy by regulating inflammatory signaling pathways. Abnormal expression of HOTAIR is positively correlated with progression, survival, and poor prognosis in different types of cancers, such as breast cancer, gastric cancer, and CRC[115-117]. Li et al[118]revealed that HOTAIR silenced the expression of the miR-218 gene by recruiting EZH2 for binding to the miR-218 promoter. Silencing of miR-218 resulted in chemotherapeutic resistance of CRC to 5-FU by promoting VOPP1 expression and eventually activating the NF-kB/TS signaling pathway. HOTAIR can thus be used as a novel prognostic indicator and therapeutic target for CRC. Inhibiting HOTAIR may be a future approach to improve the sensitivity of 5-FU chemotherapy (Figure 4, Table 2).

Table 1 MicroRNAs regulate inflammation and occurrence of colorectal cancer

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS AND CRC

Due to the inflammatory basis of CRC, anti-inflammatory agents may be candidates for treating or preventing the disease. NSAIDs are non-selective inhibitors of COX-2[119]. COX-2 is highly expressed in many tumor types, including CRC[120]. NSAIDs play a striking role in the prevention of CRC. A preliminary study on patients with familial adenomatous polyposis indicated that after 1 year of treatment with the NSAID sulindac, patients tended to exhibit a decrease in polyps[121]. A large-scale observational study in 1991 reported that the use of NSAIDs reduced the risk of fatal CRC[122]. Retrospective studies have demonstrated that NSAID treatment is associated with a decreased risk of recurrence of colorectal polyps and tumors. It has been reported that patients who use low-dose aspirin for more than 5 years show a decrease in overall risk of CRC by 40%-50%, and NSAIDs have a positive effect on advanced CRC[123,124]. NSAID therapy can also inhibit the tumor-promoting pathway by inhibiting Wnt signaling[125]. However, a meta-analysis of NSAID treatment to prevent the transformation of IBD into CRC shows that there is a lack of high-quality evidence that anti-inflammatory drugs can be used to prevent CRC in patients with IBD[126]. Most scholars believe that the anti-tumor mechanism of NSAIDs is reflected in two aspects. On the one hand, the cytokines released during inflammation play an important role in reprogramming adult stem cells into malignant cells, and NSAIDs can prevent this process[127]. On the other hand, the mechanism is related to activation of the Wnt pathway by prostaglandins[128]. However, the side effects of NSAIDs must be taken into consideration. NSAID treatment can increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, even at low doses[129]. Caution should be exercised to prevent bleeding when using anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with fragile blood vessels[130]. In addition to NSAIDs, monoclonal antibodies to cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF inhibitors have been investigated in a large number of anti-tumor studies, but most of them are still in the experimental stage[131,132]. The treatment hazard of using anti-cytokines to treat tumors is the increase in the risk of infection[133,134].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, chronic inflammation can promote the occurrence and progression of CRC, a finding that is attracting increased attention to the role of proinflammatory cytokines and immune cells in cancer. By regulating the expression of various inflammatory signaling pathways and proinflammatory cytokines, epigenetic inheritance not only participates in the transformation of inflammation into CRC but also facilitates CRC invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance. However, epigenetic inheritance accelerates the transformation of chronic inflammation into tumors through various modifications influenced by the inflammatory environment. An indepth understanding of this process will allow us to clarify the pathogenesis of CRC,and some epigenetic modifications can be used as markers for CRC diagnosis. Unlike gene mutations, which are irreversible, epigenetic inheritance is reversible or can be altered by interventions. For example, DNA demethylation promotes tumor suppressor gene expression to re-establish tumor prevention and reduce expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by regulation of histone modifications or ncRNAs,ultimately reducing inflammation infiltration of tumor microenvironment. In the future, this new anti-tumor drug may be used in combination with immunotherapy,chemotherapy, and targeted cancer therapy for the treatment of CRC. Exploring the role of epigenetics in the transformation of inflammation into CRC may help stimulate futures studies on the role of molecular therapy in CRC.

Figure 3 MicroRNAs regulate colorectal cancer progression by regulating inflammatory cytokines. CRC:Colorectal cancer; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor α; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor β.

Table 2 LncRNAs regulate the inflammation-cancer transformation

Figure 4 LncRNAs regulate the occurrence and chemotherapeutic resistance of colorectal cancer by mediating microRNAs/inflammatory signaling pathways. CRC: Colorectal cancer; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; JAK: Janus kinase.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Modified FOLFlRlNOX for resected pancreatic cancer: Opportunities and challenges

- Role of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms and functions in development of ulcerative colitis

- Postoperative complications in gastrointestinal surgery: A “hidden”basic quality indicator

- The role of endoscopy in the management of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome

- Predicting systemic spread in early colorectal cancer: Can we do better?

- NlMA related kinase 2 promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation via ERK/MAPK signaling