Childcare, Elderly Caring and Off-farm Employment of Rural Couples in China

2019-06-27YeLI

Ye LI

Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Abstract Based on the representative sample survey data of more than 1 000 farmers in 101 villages of 25 counties of 5 provinces in China, within the framework of family collective decision-making, this paper studied the effects and heterogeneity of childcare and elderly caring on the off-farm employment mode of rural couples. It found that caring the children younger than 3 years old significantly reduces the possibility of off-farm employment of rural couples; conversely, if there is 60-80 years old member in the family, it will significantly increase the possibility of off-farm employment of rural couples or the wives. Caring the children above 12 years old or the elderly older than 80 years old reduces the possibility of off-farm employment of the husbands. Whether there is preschool education service facility in the village has no effect on the off-farm employment of the couples.

Key words Off-farm employment, Rural couples, Childcare, Elderly caring, Family collective decision-making

1 Literature review

TheStrategicPlanningfortheRevitalizationofRuralAreas(2018-2022) clearly proposes to expand the space for off-farm employment of farmers, develop rural preschool education, and accelerate a home-based multi-level rural elderly caring service system[1-2]. China is in a very important period of strategic opportunities. Under the background of reduced labor supply, declining birth rate and increasing aging, how to better achieve children education, elderly caring and full employment is an important issue urgently to be solved in the current and future period[3-5]. In view of these, in-depth and systematic study of the effects of childcare and elderly caring on the off-farm employment of rural couples can provide timely and scientific references for decision-making of relevant departments, thus will have important realistic and policy significance, and will also have important academic significance. (i) According to the family economic theory, family members take the maximization of family utility as the goal of decision-making. Individual employment decision-making is not only affected by their own factors, but also influenced by the employment choices and status of other family members, showing the characteristics of collective decision-making[6-9]. Therefore, in terms of the husband-and-wife employment combination model, there are three modes: off-farm employment of both husband and wife jointly, off-farm employment of husband or wife, or off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife. In fact, most of the existing research analyzes the effects of childcare or elderly caring on the off-farm employment of rural labors from the perspective of individual decision-making[10-11]. It is worth mentioning that, based on this theory, Wang Wei made an empiric analysis on the off-farm employment decision-making of rural couples, but his analysis only based on the data of 300 farmers in 5 villages of an eastern city, so its representativeness has certain limitations[12]. (ii) Limited by data or methods, few existing studies deal with the possible heterogeneity of the effects of childcare and elderly caring on off-farm employment of rural couples. Heterogeneity is mainly reflected in the following three aspects. Firstly, the effects of childcare on off-farm employment of rural couples may vary with the age of the children. For example, infants in lactation period and before attending the kindergartens will need more care of parents (especially mothers), while older children can help care their younger brothers or sisters[13-14]. Secondly, the effects of elderly caring on off-farm employment of rural couples may vary with the age and health condition of the elderly. Healthy and not very old elderly can help care children, so it will increase the possibility of off-farm employment of rural couples[15-17]. The elderly in poor health condition need to be cared, so it will reduce the possibility of off-farm employment of rural couples[18-19]. Thirdly, the effects of childcare and elderly caring on off-farm employment of husband or wife may be different. For married men, the elderly and children may prompt their off-farm employment to reduce the financial burden of their families[20]. For married women, caring the children and elderly may reduce the possibility of their off-farm employment[13, 21]. (iii) In recent years, there are some adjustments of China’s policies, so the findings based on the data of ten years ago can not provide convincing references for making decisions in the new situation. However, few existing studies care about the important issues in the new situation. For example, China has proposed improving the preschool education service system, then what effect does the improvement of rural preschool education services have on the off-farm employment of rural labors? In other words, is there a relationship between the childcare service (public service) provided by the rural kindergarten or the preschool class and the childcare service (private service) provided by the elderly in the family? Is it substitution or complementary relationship? Through review of the existing literature, some international studies focus on the effects of childcare institutions such as kindergartens and preschools on the female labor participation rate[23-25]. By comparison, some studies focus on the effects of childcare services provided by the elderly in the family or other relatives on the off-farm employment of women[17,26]. However, by now, few literature used the rural data to analyze the relationship between public and private services of childcare and its effects on the off-farm employment of rural couples.

In this situation, with the framework of the family collective decision-making, based on the first hand survey data of farmers in 101 villages, 25 counties of 5 provinces in China, through information matching, we analyzed the effects of childcare and elderly caring on off-farm employment decision-making of rural couples and the heterogeneity of the effects. In this study, we tried to discuss the following issues: What are the effects of childcare and elderly caring in different age groups on the combined mode of off-farm employment of rural couples? Is there any heterogeneity of effects between husband and wife? Whether the preschool education service facilities in the village can alleviate the pressure of rural families in caring the children, and promote the off-farm employment of rural couples?

2 Data source

The dataset used in this paper, part of a four-wave survey named the China Rural Development Survey, was collected by authors themselves in 2016. The CRDS began in 2003, and the initial sample was a combination of stratified sampling and random sampling. First, according to the level of agriculture and economic development, we divided the whole country into five regions (Northeast, Eastern Coast, North and Central, Northwest Loess Plateau and Southwest), and selected one province from each region as the sample province: Jilin, Jiangsu, Hebei, Shaanxi and Sichuan. Second, we equally divided the counties of the sample province into five groups according to the per capita gross industrial production, then randomly selected one sample county in each group, and selected five sample counties in each province. Third, in each sample county, we divided all towns into high and low income groups according to the per capita industrial production, randomly selected one sample town from each income group, and selected two sample towns from each county. Fourth, we selected two sample villages from each town using the method for selecting sample towns. Fifth, we randomly selected 20 households from each sample village as sample households (2 000 households in total)[27].

Each round of CRDS surveys collected detailed information on the employment, migration, education, and training of each family member of the sample farmer households. It is particularly worth mentioning that in the 2016 survey, for each family member, we specifically asked the personal code of their parents; for married family members, we specifically asked the personal code of the spouse. Based on this information, it is able to accurately match the relationship between husband and wife, between parents and children, and between grandparents and grandchildren. In brief, this set of data is characterized by national representativeness and matching information on the employment, migration and basic socio-economic characteristics of couples, children and parents. This provides unique and precious data foundation for empirically analyzing the effects of childcare and elderly caring on off-farm employment decision-making of rural couples and the heterogeneity of the effects within the framework of the family collective decision-making.

In 2016, 2 026 sample households were tracked. In the actual survey, 19 out of 20 households in the previous round of survey were tracked, 20 households in seven villages that participated in the fourth round survey in 2012 were tracked and one household that has participated in the survey of 2008 was tracked, and 20 households in one village that participated in the fourth round survey in 2012 were tracked and two households that participated in the survey of 2008 were tracked, the total of households was 2 026. Considering that young people are the main body of rural off-employment labors and shoulder a heavy burden of family care, we focused on the samples who have been married, 18-45 years old and have completed education[8]. In total, 1 075 households met these criteria and became research samples of this study. We would analyze these 1 075 samples.

3 Research design

3.1 Empirical model and variable selectionWithin the framework of family collective decision-making, we firstly studied the effects childcare and elderly caring on the off-farm employment mode of rural couples. With the references[9]and[12], we set the following empirical model:

Employi=δ0+αYouthi+βOldi+γXi+μi

(1)

whereidenotes the household;Employis the explained variable and denotes the off-farm employment mode of household, including three modes: off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife (Employ=0), off-farm employment of husband or wife (Employ=1), and off-farm employment of both husband and wife (Employ=2). In this study, we took the group of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife (i.e.Employ=0) as the control group.

Youthrepresents childcare. In this study, we used whether there is child of all ages as the proxy variable for childcare. In total, we introduced five dummy variables: whether there are 0-1, 1-3, 3-6, 6-12 and 12-15 years old children in the family. The age of the child was divided because children of different ages in the family may have different needs for family time and economic resources. For example, caring the infants in lactation period and before attending the kindergartens will take more time than caring those infants that are older[26]. The more preschool children in the family, the heavier economic burden the family has[13, 21].

Oldrepresents elderly caring. In this study, we used whether there is elderly person of all ages as the proxy variable for elderly caring. In total, we introduced three dummy variables: whether there is elderly person of 60-70, 70-80 and older than 80 years old in the family. The age of the elderly was divided because the elderly of different ages in the family may have different effects on the off-farm employment decision-making of the rural couples. Healthy and not very old elderly can share the work of agricultural production or childcare and thus it will promote off-farm employment of rural couples[28]. However, if the elderly people in the family are in high age and in poor health condition, they will not be able to do farming work or care children, or even they cannot take care of themselves, as a result it will reduce the possibility of off-farm employment of rural couples[29-30].

Xdenotes other factors that do not change with the off-farm employment mode of the rural couples, including personal and spouse characteristics (such as age, educational level and mastery of skills), family characteristics (such as whether there is party member in the family, whether there is village cadre in the family, and the number of labors in the family). In order to control the effects of the county and above factors on the off-farm employment decision-making of the rural couples, we also introduced the county dummy variable into the model.α,βandγare coefficient to be estimated, andμis the stochastic error term. Since the explained variableEmployis a discrete variable with values of 0, 1 and 2, we used a multivariate logistic model for estimation. All standard errors in this study were subject to cluster adjustment at the county level.

On the basis of the model (1), we further analyzed the effects of childcare and elderly caring on off-farm employment of husband or wife. The empirical model is as follows:

(2)

whereidenotes farmer household,mdenotes individual,m=hdenotes husband,m=wdenotes wife.Workis the explained variable and denotes the off-farm employment decision making of husband or wife. The off-farm employment decision making of husband or wife includes two kinds: no off-farm employment (Work=0) and off-farm employment (Work=1). The meanings ofYouth,OldandXare the same as in the model (1).p,qandkare coefficient to be estimated, andεis the stochastic error term. Since the explained variableWorkis a variable with values of 0 and 1, we used a dual Logistic model for estimation.

In order to study the effects of rural preschool education services on the off-farm employment of rural couples and the relationship with the childcare services provided by the elderly in the family, on the basis of the model (1) and model (2), with the references[22]and[31], we firstly introduced the dummy variable (Kindergarten) of whether there is kindergarten or preschool class in the village as the proxy variable for preschool education services in the village. In addition, we added the cross term ofKindergartenand elderly caringOld, and obtained the following empirical model:

Employiv=δ0+αYouthiv+βOldiv+sKindergartenv

(3)

(4)

wherevdenotes the village where the farmer household lives,sanduare the coefficients corresponding toKindergarten,tandware the coefficients corresponding to the cross terms ofKindergartenandOld, and the remaining variables and corresponding coefficients have the same meanings as model (1) and model (2).

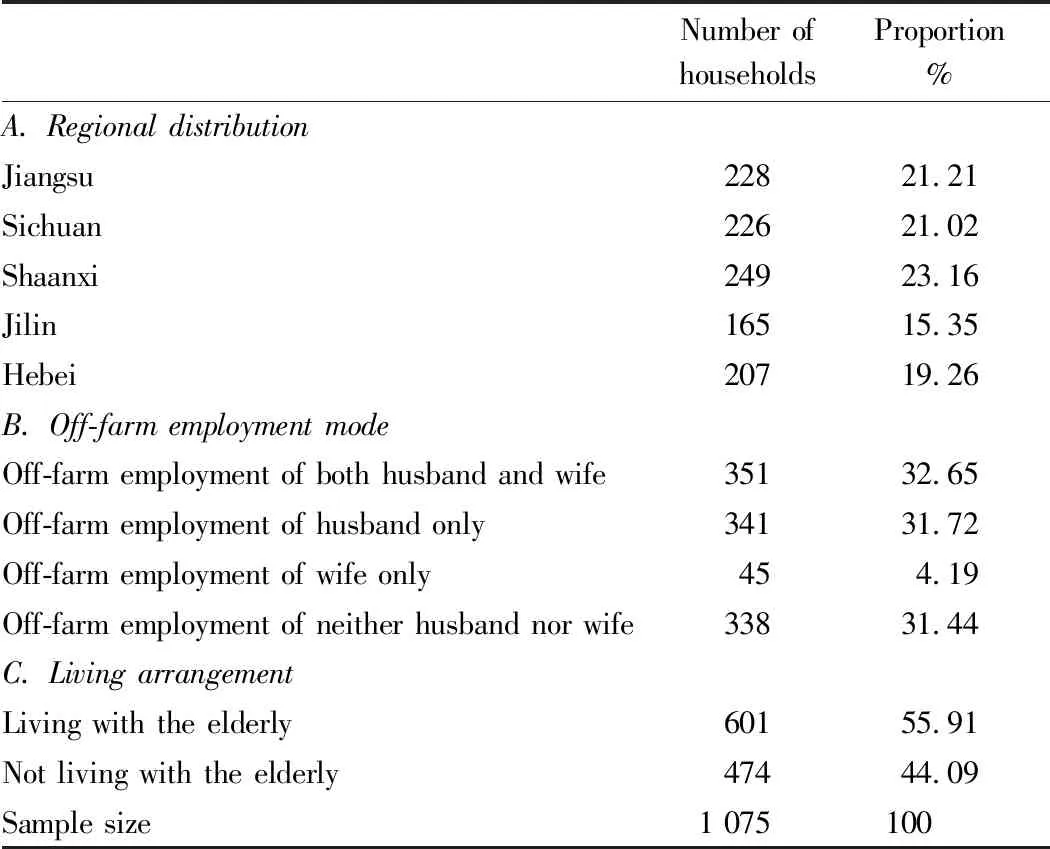

3.2 Descriptive analysisWith reference to theReportontheSurveyofMigrantWorkersin2017 issued by National Bureau of Statistics of China, we defined the off-farm employment of rural labors as employment outside the towns of their household registration for more than six months[31]. According to the statistical data, nearly 70% (specifically 68.6%) of the households have at least the husband or the wife of the couples to work outside their hometowns. The off-farm employment of both the couples accounted for the largest proportion (32%), followed by that of husband (33%), and the off-farm employment of only wife accounted for less than 4% (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of samples

Number ofhouseholdsProportion%A. Regional distributionJiangsu22821.21Sichuan22621.02Shaanxi24923.16Jilin16515.35Hebei20719.26B. Off-farm employment modeOff-farm employment of both husband and wife35132.65Off-farm employment of husband only34131.72Off-farm employment of wife only454.19Off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife33831.44C. Living arrangementLiving with the elderly60155.91Not living with the elderly47444.09Sample size1 075100

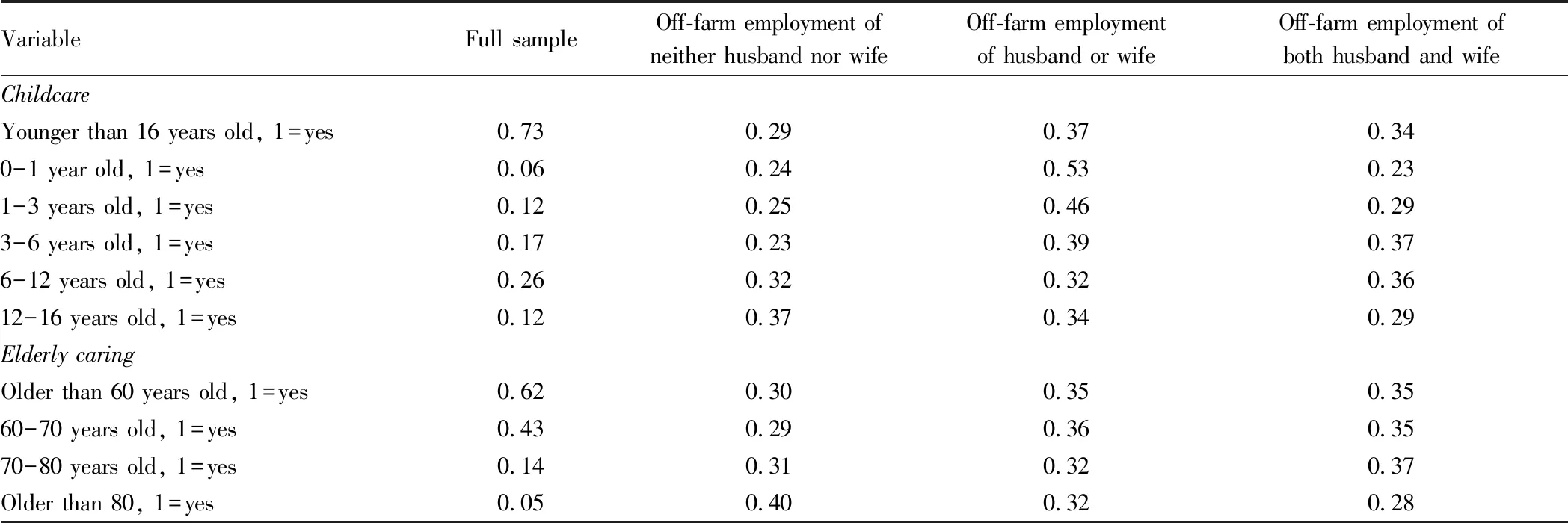

In terms of the number of children and age structure, 73% of the households had children younger than 16 years old. Among these households who had children younger than 16 years old, each household had 1.4 children on average. Households with children under one year old, 1-3, 3-6, 6-12 and 12-16 years old accounted for 8%, 16%, 23%, 36% and 18%, respectively. Compared with households without children under the age of 16, those households with children younger than 16 years old had much higher proportion of off-farm employment of one of the couples. In terms of different age group, compared with households without children under the age of 6, those households with children younger than 6 years old had much higher proportion of off-farm employment of one of the couples, but the proportion of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife was much lower. Compared with households without children above the age of 6, those households with children older than 6 years old had much higher proportion of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife, but much lower proportion of off-farm employment of husband or wife. For off-farm employment of both husband and wife, compared with households without children younger than 3 years old or without 12-16 years old children, those households with such children had much lower proportion of off-farm employment of both husband and wife; households with 3-12 years old had much higher proportion off-farm employment of both husband and wife.

In terms of the number of elderly people and age structure, 56% of the sample households lived with the elderly. Among these households who lived with the elderly older than 60 years old, each household had 1.6 elderly people on average. Households with elderly of 60-70, 70-80, and above 80 years old accounted for 43%, 14% and 5%, respectively. Compared with households without 60 years old elderly, those households with such elderly had much higher proportion of off-farm employment of one of the couples. In terms of different age groups, compared with households with the elderly under the age of 80, those households with such elderly had much higher proportion of off-farm employment of one of the couples . Compared with households without the elderly above 80 years old, those households with such elderly had much higher proportion of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife, as shown in Table 2.

In terms of the accessibility of preschool education services, only 41% of the 101 sample villages had kindergartens or preschools, indicating that there is still a long way for sample region to build rural preschool education public service network. At the household level, the accessibility of preschool education was much lower. Only 38% of the sample households had kindergartens or preschools in their villages. By comparison, households having kindergartens or preschool classes in their villages accounted for a larger proportion in the off-farm employment of at least one of the couples (Table 2).

Table 2 Descriptive analysis of childcare and elderly caring in different groups of off-farm employment modes

VariableFull sampleOff-farm employment ofneither husband nor wifeOff-farm employmentof husband or wifeOff-farm employment ofboth husband and wifeChildcareYounger than 16 years old, 1=yes0.730.290.370.340-1 year old, 1=yes0.060.240.530.231-3 years old, 1=yes0.120.250.460.293-6 years old, 1=yes 0.170.230.390.376-12 years old, 1=yes0.260.320.320.3612-16 years old, 1=yes0.120.370.340.29Elderly caringOlder than 60 years old, 1=yes0.620.300.350.3560-70 years old, 1=yes0.430.290.360.3570-80 years old, 1=yes0.140.310.320.37Older than 80, 1=yes0.050.400.320.28

In terms of the personal characteristics of the husband and wife, the average age of the husband, the number of years of education and the proportion of mastery of skills were higher than that of the wife. The average age of husband was 35 years old, and the number of years of education was 9.2 years, and the proportion of mastery of skills was 62%. The average age of wife was 33 years old, and the number of years of education was 8.6 years, and the proportion of mastery of skills was 22%. Except whether the husband has mastered the skills, there was significant difference in the off-farm employment modes of different couples between personal characteristics of the couples. By comparison, for households with off-farm employment of both the husband and wife, both the husbands and wives were the youngest and received the longest education. For households with off-farm employment of neither the husband nor the wife, both the husbands and wives were the oldest and received the shortest education. For households with off-farm employment of both the husband and wife, the proportion of the wife mastering skills was the highest. For households with off-farm employment of neither the husband nor the wife, the proportion of the wife mastering skills was the lowest (Table 3).

In terms of the family characteristics, the average number of family members per household and the number of laborers were 6 and 3, respectively, and the number of households with party members and village cadres accounted for 10% and 28% of total households respectively. Except the average number of family members per household and the number of laborers, there was no difference in the off-farm employment mode of different rural couples between households with party members or village cadres in the family. By comparison, the number of households and laborers with off-farm employment of both husband and wife was the largest, while the number of households and laborers with off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife was the smallest (Table 3).

Table 3 Descriptive analysis of personal and family characteristic in different groups of off-farm employment modes

Note: parenthetic values are standard deviation of samples, and***,**and*denote that the difference is significant at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively. Following table adopts the same meaning.

4 Multiple regression analysis

4.1 Effects of childcare and elderly caring on the off-farm employment mode of rural couples under the collective decision makingWithin the of family collective decision-making, taking the off-farm employment of neither the husband nor the wife as the control group, we empirically analyzed the effects of childcare and elderly caring on off-farm employment decision-making of rural couples. The detailed regression results are listed in Table 4. In terms of the childcare, the regression results indicate that: first, if there are children under 3 years old, it will reduce the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife, but have no effect on the off-farm employment decision making of one of the couples. Specifically, compared with the group of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife, if there are 0-1 year old children, the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife will decline by 14%; if there are 1-3 years old children, the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife will decline by 8%. These show that for the children under 3 years old, with the growth of them, their restriction on off-farm employment of both husband and wife will drop. Second, children above 3 years old basically have no effect on the off-farm employment decision-making of the rural couples. This result is consistent with previous studies. For example, Su Huashan (2013) found that if there are children to be cared, the possibility of off-farm employment of farmers will reduce by 5.8%[32].

In terms of elderly caring, if there are elderly members under 80 years old in the family, it will promote the off-farm employment of both husband and wife, but have no effect on the off-farm employment of one of the couples. Compared with the group of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife, if there are 60-70 years old elderly members, the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife will increase by 6%; if there are 70-80 years old elderly members, the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife will increase by 8%, indicating that the elderly in younger age may reduce the childcare burden of the couples through providing intergenerational care, and accordingly promote the off-farm employment of the couples[13]. However, according to findings of Liang Zhonghui and Li Min, the more elderly members in the family, the smaller possibility of off-farm employment of the couples[33]. Such inconsistency may be resulted from no division of age of the elderly[34-35].

The regression results also indicate that the effects of the age of the couple on their off-farm employment present an inverted U-shaped nonlinear relationship. With the growth of age, compared with the group of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife, the possibility of off-farm employment of either husband or wife or both husband and wife first rises then declines. Besides, the higher the educational level of the wife, the higher the possibility off-farm employment of both husband and wife. If there is village cadre in the family, the possibility off-farm employment of both husband and wife will decline. The number of laborers in the family shows a positive effect on the off-farm employment of both husband and wife.

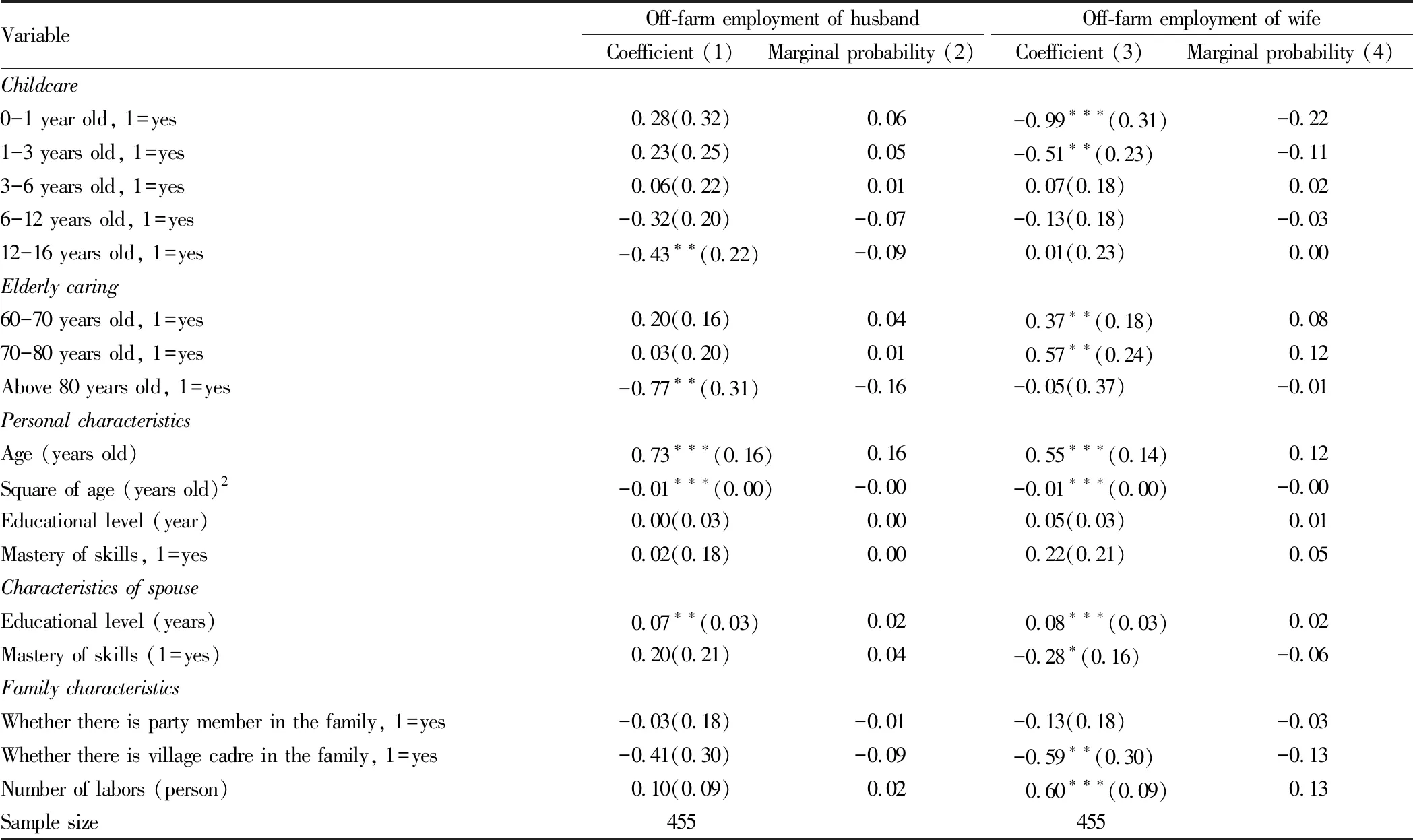

4.2 Effects of childcare and elderly caring on the off-farm employment of rural couples under the individual decision making

From the above analysis results, it is known that, within the framework of family collective decision making, the childcare and elderly caring significantly influenced the possibility off-farm employment of both husband and wife, but had no effect on the off-farm employment of either husband or wife. Thus, there is a question of whether there is a difference in the effects between childcare and elderly caring on the off-farm employment of husband and wife. We separately analyzed the regression results of effects of childcare and elderly caring on off-farm employment of husband and wife through the model (2).

Table 4 Multiple Logistic regression analysis on off-farm employment modes of rural couples

VariableOff-farm employment of husband or wifeCoefficient (1)Marginal probability (2)Off-farm employment of both husband and wifeCoefficient (3)Marginal probability (4)Childcare0-1 year old, 1=yes0.50(0.33)0.15-0.56∗∗(0.11)-0.141-3 years old, 1=yes0.31(0.25)0.09-0.29∗∗(0.17)-0.083-6 years old, 1=yes0.22(0.23)0.040.05(0.25)-0.016-12 years old, 1=yes-0.41(0.27)-0.05-0.43(0.32)-0.0812-16 years old, 1=yes-0.32(0.23)-0.03-0.34(0.26)-0.03Elderly caring60-70 years old, 1=yes0.11(0.18)-0.020.42∗∗(0.20)0.0670-80 years old, 1=yes0.07(0.25)-0.040.49∗(0.26)0.08Above 80 years old, 1=yes-0.45(0.38)-0.04-0.55(0.42)-0.05Personal characteristics of the couplesAge of husband (years old)0.48∗∗∗(0.18)-0.011.07∗∗∗(0.21)0.13Square of age of husband (years old)2-0.01∗∗∗(0.00)0.00-0.02∗∗∗(0.00)-0.00Educational level of husband (year)0.01(0.03)-0.000.05(0.04)0.01Educational level of wife (year)0.05(0.03)0.000.09∗∗(0.04)0.01Husbands mastery of skills, 1=yes0.02(0.18)0.02-0.17(0.20)-0.03Wifes mastery of skills, 1=yes0.06(0.23)-0.020.34(0.25)0.05Family characteristicsWhether there is party member in the family, 1=yes-0.05(0.21)-0.00-0.09(0.22)-0.01Whether there is village cadre in the family, 1=yes-0.12(0.29)0.05-0.74∗∗(0.33)-0.11Number of labors (person)-0.11(0.09)-0.070.50∗∗∗(0.10)0.10Sample size1 0751 075

Note: in this sample, the correlation coefficient between the age of husband and wife reached 0.92, so only the husband’s age was controlled; the parenthetic values are standard error of clustering robustness of this coefficient at the county level.

Table 5 Dual Logistic regression analysis on individual decision making of off-farm employment

VariableOff-farm employment of husbandCoefficient (1)Marginal probability (2)Off-farm employment of wifeCoefficient (3)Marginal probability (4)Childcare0-1 year old, 1=yes0.28(0.32)0.06-0.99∗∗∗(0.31)-0.221-3 years old, 1=yes0.23(0.25)0.05-0.51∗∗(0.23)-0.113-6 years old, 1=yes0.06(0.22)0.010.07(0.18)0.026-12 years old, 1=yes-0.32(0.20)-0.07-0.13(0.18)-0.0312-16 years old, 1=yes-0.43∗∗(0.22)-0.090.01(0.23)0.00Elderly caring60-70 years old, 1=yes0.20(0.16)0.040.37∗∗(0.18)0.0870-80 years old, 1=yes0.03(0.20)0.010.57∗∗(0.24)0.12Above 80 years old, 1=yes-0.77∗∗(0.31)-0.16-0.05(0.37)-0.01Personal characteristicsAge (years old)0.73∗∗∗(0.16)0.160.55∗∗∗(0.14)0.12Square of age (years old)2-0.01∗∗∗(0.00)-0.00-0.01∗∗∗(0.00)-0.00Educational level (year)0.00(0.03)0.000.05(0.03)0.01Mastery of skills, 1=yes0.02(0.18)0.000.22(0.21)0.05Characteristics of spouseEducational level (years)0.07∗∗(0.03)0.020.08∗∗∗(0.03)0.02Mastery of skills (1=yes)0.20(0.21)0.04-0.28∗(0.16)-0.06Family characteristicsWhether there is party member in the family, 1=yes-0.03(0.18)-0.01-0.13(0.18)-0.03Whether there is village cadre in the family, 1=yes-0.41(0.30)-0.09-0.59∗∗(0.30)-0.13Number of labors (person)0.10(0.09)0.020.60∗∗∗(0.09)0.13Sample size455455

Note: the parenthetic values are standard error of clustering robustness of this coefficient at the county level.

4.2.1Off-farm employment decision making of husband. According to the regression results, in terms of the childcare, whether there is child under the age of 12 in the family exerts no effect on the off-farm employment of the husband. This seems that husband takes no responsibility of caring the child[12]. However, if there is child above 12 years old in the family, the possibility of off-farm employment of husband will decline by 9%.

In terms of the elderly caring, the elderly younger than 80 years old in the family has no influence on the off-farm employment of husband. However, there is elderly member above 80 years old in the family, the possibility of off-farm employment of husband will decline by 16%. This is possibly associated with the traditional idea of "rearing sons to support the old age" in rural areas. The elderly generally live together with their sons, so the sons would undertake more caring works when their parents get old[36].

The off-farm employment decision making of husband is also affected by their personal and wives’ characteristics. There is also an inverted U-shaped relationship between the age of husband and the off-farm employment of husband. With the growth of age, the possibility of off-farm employment of husband first rises then declines. In addition, the higher the educational level of the wife, the higher the possibility off-farm employment of the husband.

4.2.2Off-farm employment decision making of the wife. According to the regression results, in terms of the childcare, the child under the age of 3 in the family greatly reduces the possibility of the off-farm employment of the wife. If there is child of 0-1 year old in the family, the possibility of off-farm employment of wife will decline by 22%. If there is child of 1-3 years old the family, the possibility of off-farm employment of wife will decline by 11%. These show that for children under 3 years old, the younger the children, the higher the restriction on off-farm employment of the wife.

In terms of elderly caring, younger elderly in the family may promote the off-farm employment of wife. If there are 60-70 years old elderly members, the possibility of off-farm employment of wife will increase by 8%; if there are 70-80 years old elderly members, the possibility of off-farm employment of wife will increase by 12%, and the elderly above 80 years old in the family has no influence on the off-farm employment of wife.

The regression results also indicate that the effects of the age of the of wife on their off-farm employment also present an inverted U relationship. With the growth of age, the possibility of off-farm employment of wife first rises then declines. If there is village cadre in the family, the possibility of off-farm employment of wife will decline. The more laborers in the family, the higher possibility of the off-farm employment of wife.

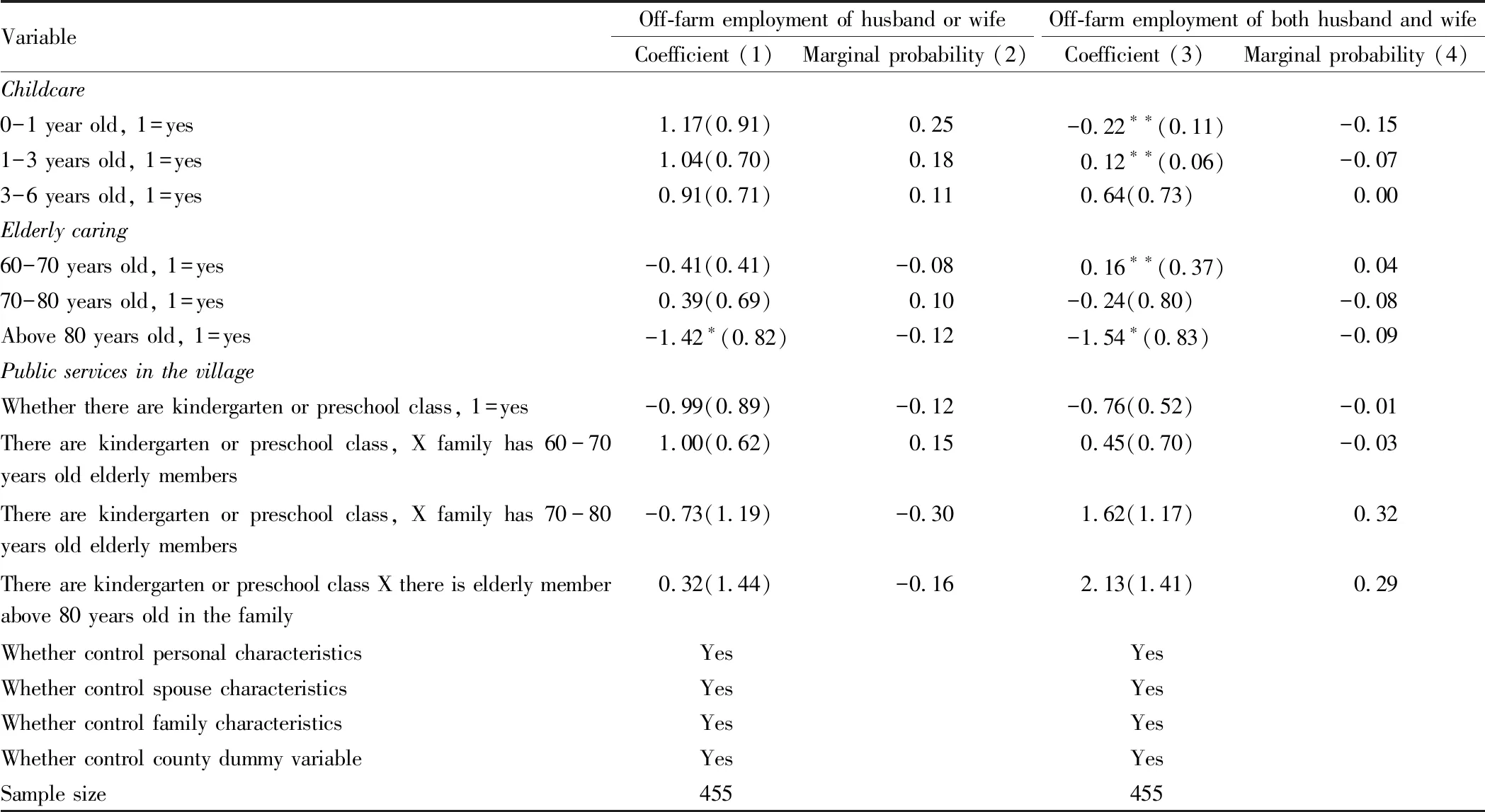

4.3 Effects of preschool education service on the off-farm employment of the couplesThe preschool education services include public services and private services. The above analysis indicated that the elderly in younger age promote the off-farm employment of the couples through intergenerational care of children. If there is preschool and kindergarten public services for childcare, is it be able to replace the private services provided by the elderly in the family to some extent, alleviate the childcare burden of farmer households, and further promote the off-farm employment of rural couples? Next, based on models (3) and (4), we limited the samples to households with 0-6 years old children in the family, and empirically answered this question. The regression results are shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6 Multiple Logistic regression analysis on-farm employment modes of rural couples (having 0-6 years old children in the family)

VariableOff-farm employment of husband or wifeCoefficient (1)Marginal probability (2)Off-farm employment of both husband and wifeCoefficient (3)Marginal probability (4)Childcare0-1 year old, 1=yes1.17(0.91)0.25-0.22∗∗(0.11)-0.151-3 years old, 1=yes1.04(0.70)0.180.12∗∗(0.06)-0.073-6 years old, 1=yes0.91(0.71)0.110.64(0.73)0.00Elderly caring60-70 years old, 1=yes-0.41(0.41)-0.080.16∗∗(0.37)0.0470-80 years old, 1=yes0.39(0.69)0.10-0.24(0.80)-0.08Above 80 years old, 1=yes-1.42∗(0.82)-0.12-1.54∗(0.83)-0.09Public services in the village Whether there are kindergarten or preschool class, 1=yes-0.99(0.89)-0.12-0.76(0.52)-0.01There are kindergarten or preschool class, X family has 60-70 years old elderly members1.00(0.62)0.150.45(0.70)-0.03There are kindergarten or preschool class, X family has 70-80 years old elderly members-0.73(1.19)-0.301.62(1.17)0.32There are kindergarten or preschool class X there is elderly member above 80 years old in the family0.32(1.44)-0.162.13(1.41)0.29Whether control personal characteristicsYesYesWhether control spouse characteristicsYesYesWhether control family characteristicsYesYesWhether control county dummy variableYesYesSample size455455

Note: the parenthetic values are standard error of clustering robustness of this coefficient at the county level.

Table 7 Dual Logistic regression analysis on individual decision making of off-farm employment (having 0-6 years old children in the family)

VariableOff-farm employment of husbandCoefficient (1)Marginal probability (2)Off-farm employment of wifeCoefficient (3)Marginal probability (4)ChildcareWhether there is child of 0-1 year old, 1=yes0.93(0.71)0.16-1.19∗∗(0.47)-0.24Whether there is child of 0-3 years old, 1=yes0.94(0.48)0.16-0.58∗∗(0.20)-0.12Whether there is child of 3-6 years old, 1=yes0.77(0.54)0.140.14(0.50)0.03Elderly caringWhether there are 60-70 years old elderly, 1=yes-0.34(0.38)-0.060.33∗∗(0.15)0.07Whether there are 70-80 years old elderly, 1=yes0.19(0.60)0.03-0.55(0.73)-0.11Whether there are elderly older than 80 in family, 1=yes-1.10∗(0.64)-0.19-1.21(0.89)-0.25Public services in the villageWhether there is kindergarten or preschool class, 1=yes-0.76(0.46)-0.15-0.13(0.38)-0.03There is kindergarten or preschool class X there is 60-70 years old elderly in the family0.56(0.62)0.220.03(0.54)-0.01There is kindergarten or preschool class X there is 70-80 years old elderly in the family0.86(0.98)0.152.00∗∗(0.93)0.41There are kindergarten or preschool class X there is elderly member above 80 years old in the family1.24(0.95)0.222.06∗(1.21)0.42Whether control personal characteristicsYesYesWhether control spouse characteristicsYesYesWhether control family characteristicsYesYesWhether control county dummy variableYesYesSample size455455

Note: the parenthetic values are standard error of clustering robustness of this coefficient at the county level.

The regression results indicate that no matter within the framework of family collective decision making (model 3) or within the framework of individual decision making (model 4), the variable estimation coefficient of kindergarten or preschool class in the village is not significant. In other words, whether there is kindergarten or preschool class in the village has no effect on the off-farm employment of rural couples. At the same time, the cross term coefficient of variable of preschool education facility in the village and elderly in the family is not significant either. In other words, in the sample region, there a no relationship between the childcare service (public service) provided by the rural kindergarten or the preschool class and the childcare service (private service) provided by the elderly in the family.

But why the preschool education service in the village has no effect on the off-farm employment of the rural couples? There are two possible reasons. On the one hand, whether there are kindergartens or preschool classes in the village cannot accurately measure the availability of local preschool education services. For example, there may be situation of share of preschool education. In rural areas, there are a large number of floating population and some villages have fewer children and do not have the conditions for running kindergartens or preschools[37]. Therefore, if there is no kindergarten or preschool class in the village, farmer households may send their children to kindergartens or preschool classes in neighboring villages or towns. On the other hand, even if there is a supply of preschool education in the village, due to problems such as imperfect infrastructure and low quality of teaching, farmer households are not willing to send their children to kindergartens or preschool classes, then the preschool education facilities in the village fail to realize the social function of childcare[38].

In terms of the childcare, the regression results based on the subsamples of those families with only 0-6 years old children are basically consistent with the results of the whole sample. First, compared with the group of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife, if there are children under 3 years old, it will reduce the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife, Second, if there are children under 16 years old in the family, it will not affect the possibility of off-farm employment of the husband. Third, if there are children under 3 years old in the family, it will reduce the possibility of off-farm employment of the wife.

However, in terms of the elderly caring, regression results based on the subsamples of those families with only 0-6 years old children have both consistency and difference with the results of the whole sample. The consistent results mainly include two aspects. Regression results based on the subsamples further indicate that, first, compared with the group of off-farm employment of neither husband nor wife, if there are 60-70 years old elderly members in the family, it will significantly increase the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife; Second, the elderly younger than 80 years old in the family has no influence on the off-farm employment of husband, but the elderly above 80 years old in the family significantly increases the off-farm employment of husband. The differences mainly include three aspects. First, based on the subsamples, the elderly of 70-80 years old in the family has no influence on the off-farm employment of both husband and wife; however, based on the whole samples, if there are 70-80 years old elderly members in the family, it will significantly increase the possibility of off-farm employment of both husband and wife. Second, based the subsamples, if there are elderly members above 80 years old in the family, it will significantly increase the possibility of off-farm employment of either husband or wife, or both husband and wife; however, based on the whole samples, the elderly above 80 years old in the family has no influence on the off-farm employment of both husband and wife; the elderly younger than 80 years old in the family has no influence on the off-farm employment of husband, but the elderly above 80 years old in the family reduce the off-farm employment of husband. Third, based on the subsamples, if there are 70-80 years old elderly in the family, it has no influence on the off-farm employment of wife; however, based on the whole samples, the results indicate that it significantly increases the possibility of off-farm employment of wife.

5 Conclusions and discussions

Based on the representative of sample survey data of more than 1 000 farmer households in 101 villages of 25 counties of 5 provinces in China, within the framework of family collective decision-making, we studied the effects and heterogeneity of childcare and elderly caring on the off-farm employment mode of rural couples, and also analyzed the effects of preschool education services on the off-farm employment of rural couples. We found that caring the children younger than 3 years old significantly reduces the possibility of off-farm employment of rural couples; conversely, if there is 60-80 years old member in the family, it will significantly increase the possibility of off-farm employment of rural couples or the wives. Caring the children above 12 years old or the elderly older than 80 years old reduces the possibility of off-farm employment of the husbands. Whether there is preschool education service facility in the village has no effect on the off-farm employment of the couples.

The empirical results in this study have important policy implications. (i) Childcare and elderly caring are important factors influencing the off-farm employment decision making of rural couples. Married women in rural areas undertake more family responsibilities of childcare. The traditional Chinese concept of "men managing internal affairs while women managing external affairs" is still widespread in sample farmer households. In rural areas, there are still numerous women laborers who can not do migrant work due to childcare[39]. Therefore, it is recommended to provide rural women with more flexible working hours in order to facilitate their off-farm employment. (ii) Intergenerational childcare provided by the elderly can alleviate the pressure on the rural couples to care for children. However, on the one hand, the rural elderly usually have several children and it is difficult to balance all the grandchildren who need to be cared[26, 40]. On the other hand, with the aggravation of population aging, both the health of the elderly and the ability to care for children decline. Childcare services provided by the elderly at home may be difficult to meet the needs of rural families[41]. Therefore, it is recommended to increase investment in rural preschool education services, strengthen the sharing of rural and township public service resources, and improve the accessibility of rural preschool education services. (iii) The quality of public services is an important factor influencing the effectiveness of public services. At present, the quality of preschool education services in rural areas in China still needs to be improved. On the one hand, the proportion of students to teachers in rural kindergartens and preschool classes are high, and teaching facilities are not perfect. On the other hand, teachers’ professional ability is weak, the course setting is not scientific, and the courses are mainly that of primary schools[42]. In this situation, it is recommended to further improve the quality of public services in rural preschool education in order to fully realize the social function of rural preschool education services in childcare.

There are some shortcomings in this study. Due to missing variables and adverse causal reasons, there may be some endogeneity between the off-farm employment of rural couples and the childcare and elderly caring. Besides, due to limitations in cross-section data, it is difficult to solve endogenous problems. Thus, the further study should focus on the application of panel data and analysis of causal recognition strategies.

杂志排行

Asian Agricultural Research的其它文章

- Delimitation and Zoning of Natural Ecological Spatial Boundary Based on GIS

- Career Planning Education Paths for Students of Aquatic Animal Medicine Discipline in the Context of the Belt and Road Initiative: A Case Study of Construction Achievement of Guangdong Ocean University

- Pilot-scale Study on NCMBR Process for Upgrading of Sewage Treatment Plant in Industrial Park

- Preliminary Exploration on Design of Green Landscape of Urban Streets: A Case Study of Guangchang East Road in Xihu District of Nanchang City

- Present Situation and Renovation Strategies of Farmhouses in Yingxi Village, Fuliang County, Jingdezhen

- Influence of Sino-US Agricultural Trade on China’s Total Agricultural Output Value Based on Cointegration Model