Viewpoints of the target population regarding barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in the Czech Republic

2019-03-11RadekKroupaMonikaOndrackovaPetraKovalcikovaMilanDastychTomasPavlikLumirKunovskyJiriDolina

Radek Kroupa, Monika Ondrackova, Petra Kovalcikova, Milan Dastych, Tomas Pavlik, Lumir Kunovsky,Jiri Dolina

Abstract BACKGROUND Public awareness of colorectal cancer (CRC) and uptake of CRC screening remain challenges. The viewpoints of the target population (asymptomatic individuals older than 50) regarding CRC screening information sources and the reasons for and against participation in CRC screening are not well known in the Czech Republic. This study aimed to acquire independent opinions from the target population independently on the health system.AIM To investigate the viewpoints of the target population regarding the source of information for and barriers and facilitators of CRC screening.METHODS A survey among relatives (aged 50 and older) of university students was conducted. Participants answered a questionnaire about sources of awareness regarding CRC screening, reasons for and against participation, and suggestions for improvements in CRC screening. The effect of certain variables on participation in CRC screening was analyzed.RESULTS Of 498 participants, 478 (96%) respondents had some information about CRC screening and 375 (75.3%) had participated in a CRC screening test. General practitioners (GPs) (n = 319, 64.1%) and traditional media (n = 166, 33.3%) were the most common information sources regarding CRC screening. A lack of interest or time and a fear of colonoscopy or positive results were reported as reasons for non-participation. Individuals aged > 60 years [adjusted odds ratio(aOR) = 2.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) (1.42-3.71), P = 0.001], females (aOR =1.95, 95%CI (1.26-3.01) P = 0.003), and relatives of CRC patients (aOR = 4.17,95%CI (1.82-9.58) P = 0.001) were more likely to participate in screening.Information regarding screening provided by physicians - GPs: (aOR = 8.11,95%CI (4.90-13.41), P < 0.001) and other specialists (aOR = 4.19, 95%CI (1.87-9.38),P = 0.001) increased participation in screening. Respondents suggested that providing better explanations regarding screening procedures and equipment for stool capturing could improve CRC screening uptake.CONCLUSION GPs and other specialists play crucial roles in the successful uptake of CRC screening. Reduction of the fear of colonoscopy and simple equipment for stool sampling might assist in improving the uptake of CRC screening.

Key words: Colorectal cancer; Screening; Colonoscopy; General practitioner; Patient compliance; Fecal occult blood test

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common cause of cancer-related mortality in many developed countries. In 2015, the crude, adjusted to world standard (ASR-W) and adjusted to European standard (ASR-E) incidences of CRC in the Czech Republic were approximately 76.4, 35.8, and 52.8 per 100000 inhabitants, respectively[1].The Czech Republic is one of the countries with the highest incidence rates of CRC worldwide[2].There is a wide body of evidence on decreased CRC mortality and incidence as a result of screening strategies that employ fecal occult blood testing and colonoscopy[3-5]. Observational studies and the micro simulation screening analysis colon model suggested that CRC screening led to a 50% reduction in CRC-related mortality[6,7].

A National CRC Screening program was started in the Czech Republic in 2000, and it was further enhanced in 2009[8]. In this program, general practitioners (GPs) and gynecologists are key people responsible for inviting individuals to screen for CRC.Their efforts are supported by invitations to visit GPs, which are mailed to persons in screening age without any previous attendance in the screening by health insurance companies[9]. Currently, immunochemical fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs) are offered to asymptomatic individuals aged > 50 years annually for CRC screening;colonoscopy is offered in the case of positive test results. Alternatively, people aged ≥55 years can either continue to undergo FOBTs every 2 years or they can decide to have a colonoscopy as a primary screening modality, which is reliable enough to be performed in 10-year intervals[10].

The effect of the National CRC Screening Program over the last ten years in the Czech Republic can be observed. Although the crude, ASR-W, and ASR-ECRC incidences decreased from 44.5, 23.8, and 37.8 per 100000, respectively, in 2001 to 35.6,14.6, and 22.9 per 100000, respectively, in 2015, the actual participation of asymptomatic individuals in screening procedures (approximately 30% in 2016[11]) is still far from the desired rate[12]. Results of CRC screening programs are often presented from the viewpoints of stakeholders, care providers, and endoscopists[8,13].Studies describing the viewpoint of clients in the target population are rare. Only one study using a questionnaire distributedviaemail to the employees of a large successful business company in the country has been conducted so far[14]. Moreover,interviews/questionnaires completed by care providers(GPs and gastroenterologists)may be skewed due to the lack of representative data, and the relationship between patient and physician may lead patients to minimize the health issues referenced.Evaluation of screening procedures from the viewpoints of clients might be an important tool for quality assurance and may contribute to further improvements and efficacy of such programs[12].

This study aimed to acquire independent opinions from the target population for CRC screening regarding CRC screening information sources and the reasons for and against participation in CRC screening. Clients’ personal feelings regarding screening perceptions and potentially problematic points in the screening process were also surveyed. The effect of certain factors on initial and longitudinal screening uptake was assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from 2013 to 2015 (a consecutive 3-year period). Anonymous printed questionnaires were distributed to the relatives of pregraduate university students and to students of The University of the Third Age at the Masaryk University in Brno. Most of the respondents lived in Moravian regions of the Czech Republic. All the participants recruited were in the target age range for CRC screening (50-80 years). Students were asked for personal assistance in the distribution and collection of the questionnaires. With the exception of those in their first year of the study (i.e., 2013), respondents may have been informed about CRC screening by personalized invitations to participate in a screening program, which was managed by health insurance companies.

Questionnaires

The questionnaires asked participants for information pertaining to their demographic characteristics, if they ever had a CRC screening test, sources of information regarding CRC screening programs, and reasons for non-participation in CRC screening. All subjects were asked about challenges and barriers associated with screening tests that affected their participation or lack thereof based on their personal experiences and feelings. Respondents were encouraged to indicate what promoting factors might be useful for CRC screening support. The questionnaires consisted of multiple choice questions for each category. There were no open ended/free write questions included.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequencies, means, standard deviations (SDs), and minimum and maximum values were used to describe the study population and questionnaire responses. Statistical comparisons were performed between subjects who had undergone screening and those who had not.We evaluated differences between subgroups using Pearson's chi-square tests. The differences between the ages of group members according to participation were calculated using Mann-Whitney tests.

Potential predictor variables for participation in screening (demographic characteristics and sources of information regarding CRC screening) were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for age, gender, history of CRC in family, letter of invitation and sources of information. Adjusted odds ratios(aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. APof < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software version 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for the statistical analyses.

Ethics

The study was approved by the local ethical committee at the Brno University Hospital. All participants provided informed consent to anonymously analyze their answers. No individualized personal data were collected.

RESULTS

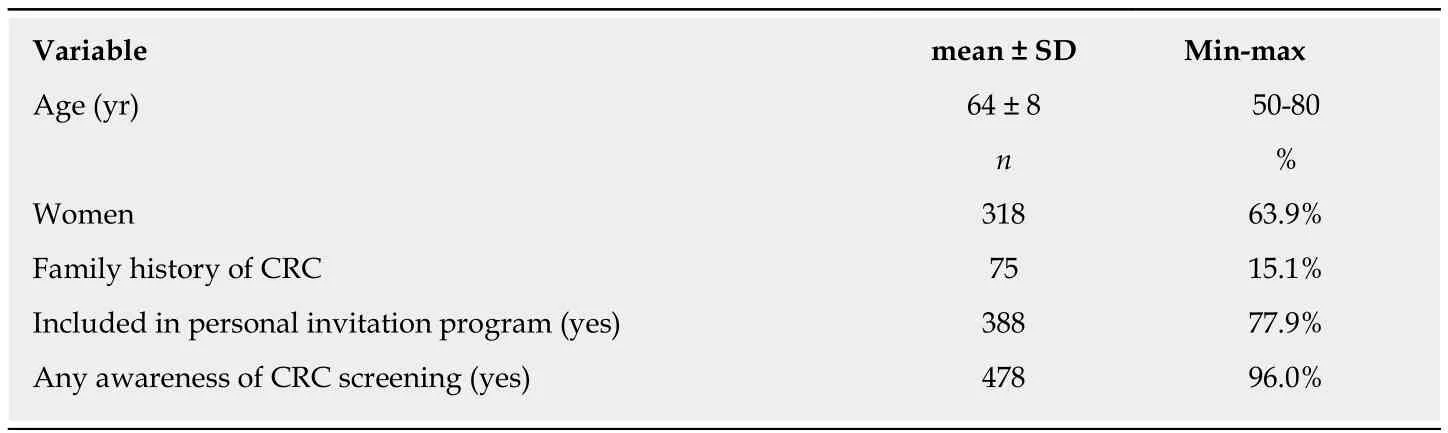

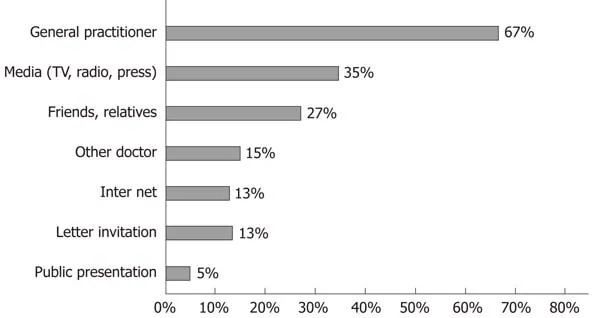

In total, 1200 questionnaires were distributed over the study period, and completed questionnaires were obtained from 498 persons, yielding a response rate of 41.5%. The respondents consisted of 318 (63.9%) women, and the mean age ± SD was 64 ± 8 years(Table 1). The majority of respondents (n= 388, 77.9%) were included in the survey from 2014 to 2015, when the personal invitation program was active. Overall, 478 respondents had received some education regarding CRC screening. Nearly half of the informed respondents (n= 229, 47.9%) had received information about CRC screening from more than one source. GPs were the main information source regarding CRC screening (n= 319, 66.7%), followed by traditional media, including TV, radio, and newspapers (n= 166, 34.7%, Figure 1). Personal information from friends or relatives comprised a substantial proportion of information sources (n=130, 27.2%). Letters from Health Insurance Companies were only reported as a source of information in 64 (13.4%) respondents.

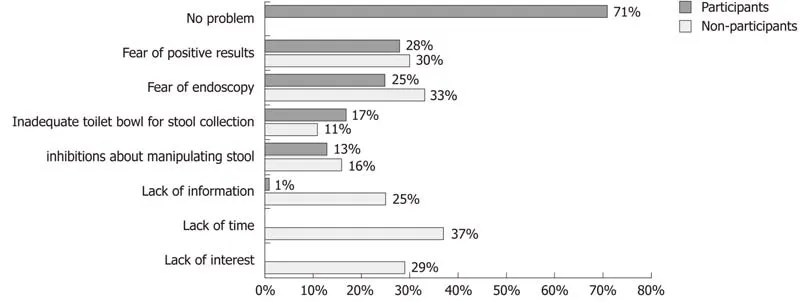

Reasons for non-participation

Only 123 (24.7%) respondents had never participated in a screening. Reasons for nonparticipation were as follows: A lack of interest (n= 35, 28.5%), not enough time to visit the doctor (n= 46, 37.4%), fear of colonoscopy and/or preparation for the procedure (n= 41, 33.3%), and fear of positive test results (n= 37, 30.1%, Figure 2).Inhibition about manipulating stool and practical issues regarding FOBTs also hampered participation in 27 (21.9%) respondents. In the group of respondents educated on CRC screening, 375 (75.3%) had participated in some method of screening. In 231 (61.5%) respondents, FOBTs had been conducted, while FOBT,colonoscopy and primary colonoscopy screening had been conducted in 112 (29.9%)and 32 (8.5%) respondents, respectively. More than one third of respondents (n= 180,36.1%) had undergone repeat screening tests.

Respondents were asked about any issues that might theoretically hamper further CRC screening tests (Figure 2). The majority of respondents (n= 265, 70.7%) reported that they would undergo subsequent CRC screening without any relevant barriers.However, fears of colonoscopy and/or preparation for the procedure (n= 94, 25.1%)and of positive results (n= 104, 27.7%) were referred to as possible problems. Seventy seven (20.5%) respondents reported that they experienced technical difficulties with capturing stool in the toilet bowl and that they were embarrassed about manipulating stool.

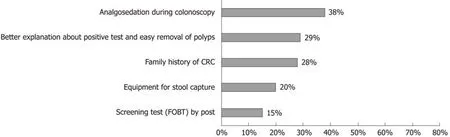

Suggested screening facilitators

A list of suggestions to increase the uptake of CRC screening was presented to all subjects. Only 75 (15.1%) respondents responded positively to the idea of delivery and return of FOBT screening testsviathe post (Figure 3). 100 (20.1%) respondents desired better equipment for stool collection. Interestingly, 142 (28.5%) respondents reported being aware that a positive screening test did not directly relate to a diagnosis of cancer, might increase participation in these tests. Finally, a significant proportion of subjects (n= 189, 38.0%) suggested better publicity of colonoscopy with a focus on analgosedation during the procedure and a reduction of inconvenience.

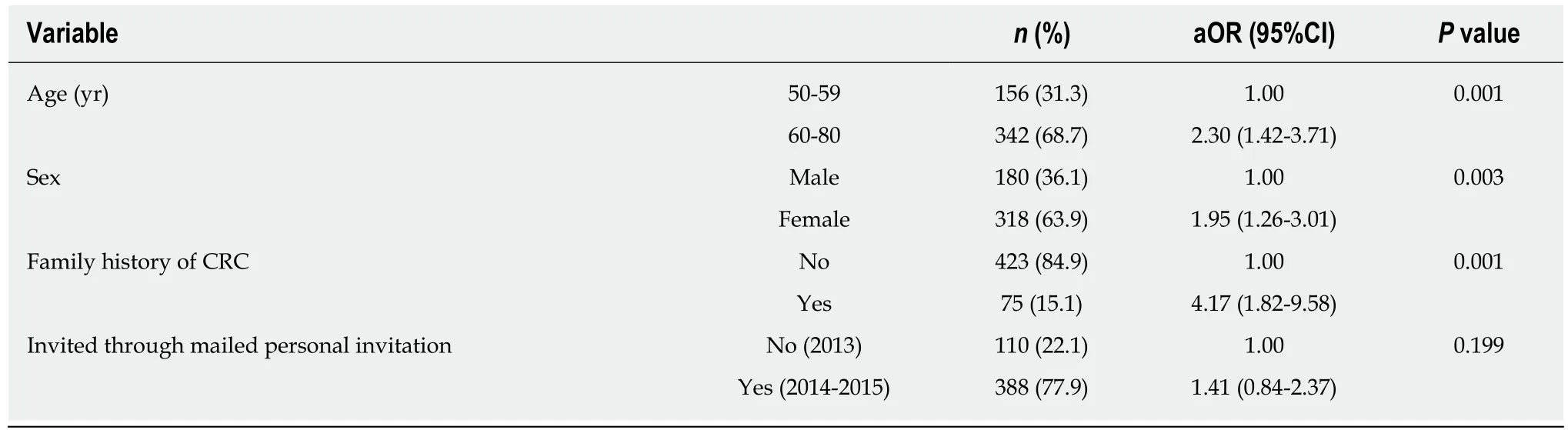

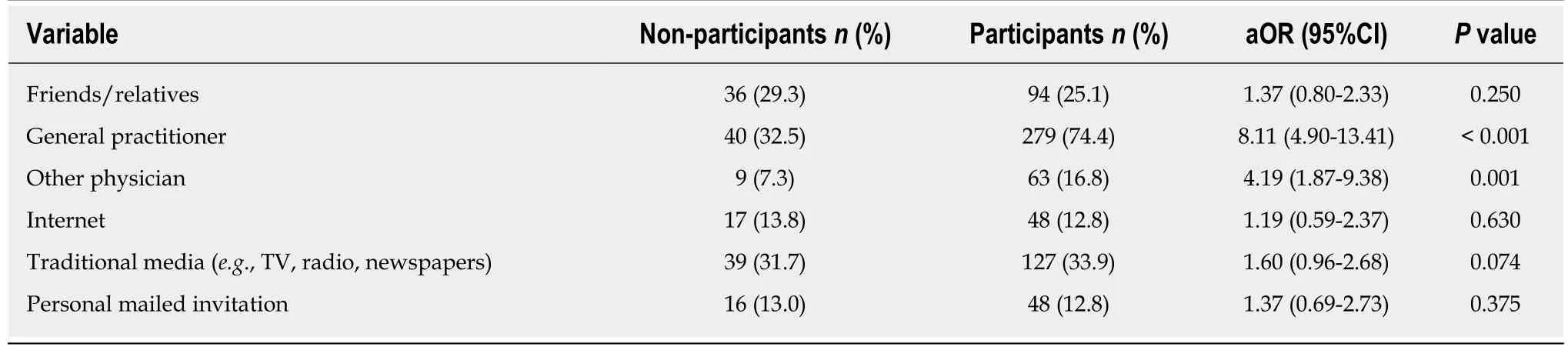

Analysis of screening participation

Demographic factors of respondents who participated in CRC screening were analyzed using a multivariate model (Table 2). Uptake of any screening method was more common in women (aOR = 1.95, 95%CI 1.26-3.01), those with a family history of CRC (aOR = 4.17, 95%CI 1.82-9.58), and those aged > 60 years (aOR = 2.30, 95%CI 1.42-3.71). Respondents enrolled in the study in the years 2014-2015, when the personal invitation program had been introduced, were as likely to participate in the screening as those enrolled in year 2013 (aOR = 1.41, 95%CI 0.84-2.37). We also investigated whether the source of information regarding screening influenced the participation rate (Table 3). When informed by GPs (aOR = 8.11, 95%CI 4.90-13.41) or another physician (aOR = 4.19, 95%CI 1.87-9.38) about screening, respondents were more likely to participate in screening than those who had never been informed. None of the other sources of information influenced the screening uptake.

DISCUSSION

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the study population (n = 498)

In this study, we investigated the viewpoints of the target population regarding the source of information for and barriers and facilitators of CRC screening. Overall, we found that the majority of respondents from the target population received their education regarding CRC screening from their GPs. Our findings support the role of GPs in the recruitment of asymptomatic individuals for CRC screening programs.Active interventions led by GPs for non-participants appears to be a feasible mechanism for increased participation rates[15,16]. Although personalized invitations in the Czech Republic can hypothetically coverall non-participants in the screening program, the gain as a result of this activity will have limits. Our data did not support the increased uptake in screening among the target population following the distribution of mailed invitations to participate in CRC screening. The largest impact was observed after the first round of invitations was sent. In subsequent years of the program, the response rate slowly declined[11]. The role of direct physician advice seemed to be more important.

Most standard medical care is covered by the general health insurance system without any costs to the patient in the Czech Republic. CRC screening might be perceived by asymptomatic persons from the general population as one of many“excessive” health system services, which not have much personal benefit. Public awareness regarding stool, bowel problems, and CRC is poor when compared to awareness of breast and cervical cancer[13,17,18]. Even among health professionals, there is a low compliance to CRC screening when compared to breast and cervical cancer screening[19]. Health care professionals should engage with asymptomatic patients to provide them with general health advice and prevention techniques (e.g., occupational safety and health checks, clinical examinations at hospital admission for any reason,consultations with surgeons, oncologists, or internists,etc.) to increase awareness regarding CRC screening. Patients may be willing to accept any of the suggested screening methods when encouraged by a physician at the time of a clinical visit[13].Optimally, health care professionals should have discussions regarding patients’fears, provide patients with written recommendations in a medical report, and require patients to have FOBT in scheduled intervals or make appointments for preventive colonoscopies. A more receptive attitude toward screening may be achieved if physicians emphasize its importance. Clear and easy instructions from physicians can impact patients’ submission to screening[20]. Conversely, patients should be informed about the theoretical risks of colonoscopy and health care professionals should avoid providing unfeasible guarantees regarding the lack of cancer development in the future[21]. One study found that the mean waiting time for a colonoscopy in the Czech Republic did not exceed 2 months[22]; thus, this is likely not a reason for nonparticipation.

We also found that a fear of colonoscopy could be an important reason for nonparticipation, even in previously screened patients. Fear of pain and discomfort are often reasons for not having a colonoscopy[23]. Unfortunately, the questionnaire did not distinguish fear of colonoscopy from fear regarding bowel preparation for the procedure. The bowel cleansing might be perceived as a troublesome factor for repetitive colonoscopy in some individuals, even more so than endoscopy alone[24].The prescription of low volume formulas in split dose regimens could be considered without a substantial risk of inadequate bowel cleansing[25].

Figure 1 Information sources regarding the colorectal cancer screening program as identified by survey respondents (n = 478).

Standard colonoscopy screening is usually performed with midazolam sedation and combined with opioid analgesics in some patients. The use of propofol in the Czech Republic is limited to anesthesiologists; thus, it is expensive and rarely available. In some countries (Germany and Switzerland), propofol can be administered by trained non-anesthesiologist health care professionals during colonoscopy[26]. Propofol can significantly decrease pain during colonoscopy and thus might increase CRC screening uptake rates[27]. Colonoscopy is the most effective preventive tool to reduce mortality from CRC; it has been shown to reduce mortality rates by up to 60%[28]. Patients might be further encouraged to choose this screening method if there were easy access to analgesia during the procedure and if there was a more robust explanation of its preventive aspects, including the easy removal of precancerous lesions in the bowel. Based on our data, avoiding stool manipulation might also increase uptake for patients. Replacement of colonoscopy by any noninvasive screening method (e.g., miRNA detection) is still far from clinical practice[29].

Compared to the study conducted by Králet al[14], we used a different strategy to distribute questionnaires only to the respondents in our target age group. Our results are similar to those previously reported, as we observed higher rates of screening uptake among females and those aged ≥ 60 years. Our data shed light on factors associated with uptake of CRC screening and provide new data regarding attitudes toward colonoscopies. Additionally, the effect of personalized invitations could be assessed due to our more recent study period. To our knowledge, only our study and that conducted by Králet al[14]have investigated the attitudes of the target population regarding CRC screening program in the Czech Republic.

Our study had several limitations that warrant further discussion. The sample of respondents is not fully representative of the general population and it was relatively small. The participation rate for the uptake of CRC screening was considerably higher than 30%, thus exceeding that of the rate in the country. We assume that more active respondents who are interested in their health were more likely to return the questionnaires. A bias due to the relatively high education level of the interviewed subjects may affect results too. Nevertheless, the questionnaires were completely independent of health care services provided. Additionally, this study is limited as we did not cover of all of the barriers and facilitators regarding screening uptake. There were no open ended/free write questions included. Despite these limitations, the main goal of the study, which was to determine the opinions of the target population regarding CRC screening, was achieved. Our survey might increase the awareness regarding CRC screening in family members of university students and stimulate uptake of screening. Moreover, our findings have implications for clinical practice,since they provide evidence that GPs play a key role in providing education about CRC screening for the target population. Better communication regarding the results of screening tests and related benefits could increase participation rates. Czech patients may opt in more frequently if they are informed about screening by their physicians rather thanviaa letter. Patients should routinely be informed about and motivated to undergo CRC screening during any health consultation,e.g., internal medicine, surgery, and oncology consultations, not only in GP consultations.Conversely, a digital rectal exam is an essential part of many health checks, which may be embarrassing for some patients. Asymptomatic rectal cancer is rarely diagnosed by digital rectal exam and evidence for this approach to influence CRC mortality is lacking[30,31].

In conclusion, GPs and other specialists play a crucial role in improving the uptake of CRC screening, while other educational tools were less effective. Reduction of the fears of colonoscopy by focused campaigns, routine use of analgosedation, and better equipment for stool sampling might encourage the target population to participate in screenings. In the future, regular surveys of the target populations’ attitude toward CRC screening may improve the participation in and efficacy of the program.

Table 2 Multivariate logistic regression analysis of demographic factors associated with the screening uptake (n = 498)

Table 3 Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the sources of information about colorectal cancer screening associated with the screening uptake (n = 498)

Figure 2 Issues identified among respondents for the lack of screening in non-participants (n = 123) or difficulties in repeat screening attendance in former participants (for whom screening was conducted, n = 375).

Figure 3 A list of suggestions for increased colorectal cancer screening uptake based on respondents’ subjective views (n = 498). CRC: Colorectal cancer;FOBT: Fecal occult blood test.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The Czech Republic is one of the countries with the highest incidence rates of colorectal cancer(CRC) worldwide. The actual participation of asymptomatic individuals in screening procedures(approximately 30% in 2016) is still far from the desired rate. Public awareness of CRC and uptake of CRC screening remain challenges.

Research motivation

The viewpoints of the target population (asymptomatic individuals older than 50) regarding CRC screening information sources and the reasons for and against participation in CRC screening are not well known. Tailored screening support and promotion may increase participation rates and efficacy of screening program.

Research objectives

This study aimed to acquire independent opinions from the target population regarding CRC screening information sources and the reasons for and against participation in CRC screening,independently on the health system.

Research methods

A survey among relatives (aged 50 and older) of university students was conducted. Participants answered a questionnaire about sources of awareness regarding CRC screening, reasons for and against participation, and suggestions for improvements in CRC screening. The effect of certain variables on participation in CRC screening was analyzed.

Research results

The majority of respondents had some information about CRC screening. General practitioners(GPs) (64.1%) and traditional media (33.3%) were the most common information sources regarding CRC screening. Only 24.7% respondents had never participated in a screening. A lack of interest or time and a fear of colonoscopy or positive results were reported as reasons for nonparticipation. Individuals aged > 60 years, females and relatives of CRC patients were more likely to participate in screening. Information regarding screening provided by physicians - GPs and other specialists increased participation in screening importantly. Respondents suggested that providing better explanations regarding screening procedures and equipment for stool capturing could improve CRC screening uptake.

Research conclusions

GPs and other specialists play a crucial role in improving the uptake of CRC screening, while other educational tools were less effective. Reduction of the fears of colonoscopy by focused campaigns, routine use of analgosedation, and better equipment for stool sampling might encourage the target population to participate in screenings.

Research perspectives

In the future, regular surveys of the target populations’ attitude toward CRC screening may gain interesting facts for further improvement of the screening program. Focus on the role of physician’s advice for the screening participation and better communication during routine health consultation regarding the results of screening tests and related benefits could increase participation rates.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Liver stem cells: Plasticity of the liver epithelium

- Reaction of antibodies to Campylobacter jejuni and cytolethal distending toxin B with tissues and food antigens

- Integrated network analysis of transcriptomic and protein-protein interaction data in taurine-treated hepatic stellate cells

- Computed tomography scan imaging in diagnosing acute uncomplicated pancreatitis: Usefulness vs cost

- Targeted puncture of left branch of intrahepatic portal vein in transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt to reduce hepatic encephalopathy

- Optimized protocol of multiple post-processing techniques improves diagnostic accuracy of multidetector computed tomography in assessment of small bowel obstruction compared with conventional axial and coronal reformations