Obesity, metabolic abnormalities, and mortality in older men

2018-08-17RongZHANGShengYongDONGWeiMinWANGShuYangFEIHangXIANGQiangZENG

Rong ZHANG, Sheng-Yong DONG, Wei-Min WANG, Shu-Yang FEI, Hang XIANG, Qiang ZENG

Obesity, metabolic abnormalities, and mortality in older men

Rong ZHANG1,2,*, Sheng-Yong DONG3,*, Wei-Min WANG1, Shu-Yang FEI4, Hang XIANG1, Qiang ZENG1

1Health Management Institute, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China2Department of Cardiology, Chinese Navy General Hospital, Beijing, China3Healthcare Department, Agency for Offices Administration of PLA, Beijing, China4Department of Clinical Medicine, School of Preclinical Medicine, Capital University of Medical Sciences, Beijing, China

Older adults are prone to obesity and metabolic abnormalities and recommended to pursue a normal weight especially when obesity and metabolic abnormalities are co-existed. However, few studies have reported the possible differences in the effect of obesity on outcomes between older adults with metabolic abnormalities and those without metabolic abnormalities.A total of 3485 older men were included from 2000 to 2014. All-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were obtained during a mean follow-up of five years. Metabolic abnormalities were defined as having established hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia and taking the disease-related medications. All participants were stratified by the presence or absence of metabolic abnormalities.In the non-metabolic abnormalities group, all-cause and cardiovascular deaths were lowest in overweight participants and highest in obese participants. In the metabolic abnormalities group, mortality was also lowest in overweight participants but highest in participants with normal weight. After adjustment for covariates, hazard ratios (95% CI) for all-cause death and cardiovascular death were 0.68 (0.51, 0.92) and 0.59 (0.37, 0.93), respectively, in overweight participants with metabolic abnormalities. Furthermore, obesity was not associated with mortality risk in both groups. These findings were unchanged in stratified analyses.Overweight was negatively associated with mortality risk in older men with metabolic abnormalities but not in those without metabolic abnormalities. Obesity did not increase death risk regardless of metabolic abnormalities. These findings suggest that the recommendation of pursuing a normal weight may be wrong in overweight/obese older men, especially for those with metabolic abnormalities.

J Geriatr Cardiol 2018; 15: 422427. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2018.06.004

Obesity; Older men; Metabolic abnormality; Mortality

1 Introduction

Obesity is closely associated with metabolic abnormalities.[1,2]Both of obesity and metabolic abnormalities are independent factors of cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality.[1,3,4]The literature reports that metabolic abnormalities are closer to CVD risk and death than obesity in the general population.[5–7]Our previous study also reported that associations of obesity with CVD risk were attenuated and even nonexistent after an individual had developed metabolic abnormalities in a middle-aged population.[8]However, few studies have reported whether such differences between population with metabolic abnormalities and those without metabolic abnormalities are exist in older adults.

Although a number of studies have shown that obesity increases adverse outcomes in the general population and recommended overweight or obese populations to pursue a normal weight,[9–11]the effects of obesity on prognosis in population with established diseases are still controversial.[3,12]Recent studies have reported a protective effect of obesity on prognosis in population with coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, or other certain diseases.[12–14]According to these controversial findings, it is expected that the effect of obesity on outcomes may be different between older adults without metabolic abnormalities and those with established metabolic abnormalities; however, similar studies are limited.

Older adults are prone to obesity as well as metabolic abnormalities.[15]Research on associations of obesity and metabolic abnormalities with health outcomes will help to manage obesity individually and maintain health in older adults. Therefore, the present study was to investigate associations between obesity and mortality in Chinese older men with or without metabolic abnormalities.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

The present study recruited older men who visited the Chinese PLA General Hospital from Jan 2000 to Dec 2014. Inclusion criterion was men with age older than 60 years. Exclusion criteria were participants with previously diagnosed coronary heart disease, heart failure, kidney disease, liver disease, lung disease, stroke, thyroid disease, anemia, mental disease, or cancer. Participants who had a body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2were also excluded due to the increased probability of preexisting disease. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital.

2.2 Covariates

Data on smoking status and medical history were obtained by a self-reported questionnaire. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg and height to the nearest 0.1 cm. Systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and serum creatinine were measured by routine methods.

2.3 Definition of obesity and metabolic abnormalities

Based on the recommendation by the Working Group on Obesity in China,[16]BMI levels were categorized into: normal weight, BMI < 24 kg/m2; overweight, 24–27.9 kg/m2; and obese, ≥ 28 kg/m2.

Refer to the definition of metabolic syndrome by the Chinese Guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Adults,[17]metabolic abnormalities were defined as having one abnormality or more abnormalities as follow: (1) having been previously diagnosed as hypertension and taking anti-hypertensive medications; (2) having been previously diagnosed as diabetes and taking antidiabetic medications; and (3) having been previously diagnosed as dyslipidemia and taking antilipemic medications.

2.4 Follow-up and outcomes

Participants were followed until December 2016. Information on mortality was obtained from death certificates, hospital records, and telephone contacts with family members. The primary outcomes were all-cause and cardiovascular death, which were defined by the tenth revision of the International Classification of Disease.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Data are shown as mean ± SD or(%), as appropriate. Participants were stratified into two groups by the presence or absence of metabolic abnormalities. Differences between groups were analysed using one-way analysis of variance or chi-square tests. Non-normally distributed variables were log transformed before the analyses. Age-standardized death per 1000 person years were calculated and direct method of standardization was used. Kaplan-Meier plots were generated to visualize cumulative survivals among BMI categories. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess associations between BMI and mortality risk. Participants were finally stratified into subgroups by age (60-69, 70-79, and ≥ 80 years), smoking status (non-smoking or ex-smoker and current smoking), the presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, and the number of metabolic abnormalities. Associations between BMI and mortality risk were assessed in each subgroup individually. A two-sidedvalue < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics

A total of 3485 older men were included in the present study. Among them, 61.3% had metabolic abnormalities (Table 1). Compared to the participants without metabolic abnormalities, those with metabolic abnormalities were older and had higher levels of BMI, systolic blood pressure, total and LDL cholesterols, and serum creatinine but lower percentage of current smoking (< 0.001 for all). As shown in Figure 1, the prevalence of overweight and obesity both increased from the non-metabolic abnormalities group to the metabolic abnormalities group (< 0.001).

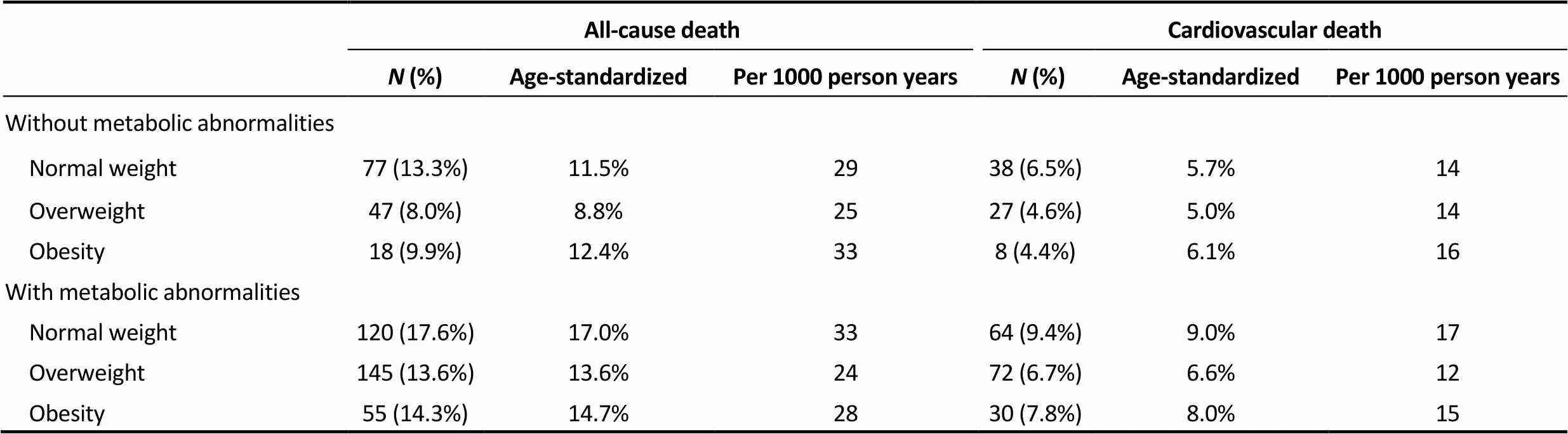

3.2 Mortality and BMI categories

All of the included participants finished a mean follow-up period of five years. A total of 462 death occurred and 239 of them were due to cardiovascular causes. In the non-metabolic abnormalities group, overweight participants had the lowest age-standardized all-cause death (25 per 1000 person years) and age-standardized cardiovascular death (14 per 1000 person years), and obese participants had the highest age-standardized all-cause and cardiovascular deaths (Table 2). In the metabolic abnormalities group, overweight participant also had the lowest age-standardized death, but age-standardized deaths for all-cause and cardiovascular causes were highest in participants with normal weight.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of older men with or without metabolic abnormalities.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or(%). *Hypertension indicated that the participants had been previously diagnosed as hypertension and took anti-hypertensive medications at baseline. Similar definitions also applied to diabetes and dyslipidemia. BMI: body mass index; LDL: low-density lipoprotein.

Figure 1. BMI categories of older men with or without metabolic abnormalities.< 0.001 when the differences of BMI categories between the participant without metabolic abnormalities and the participants with metabolic abnormalities were compared. BMI: body mass index.

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of older men are presented in Figure 2. In metabolic abnormalities group, overweight participants had the best survival probability and participants with normal weight had the worst survival probability (log-rankvalues were 0.009 and 0.036 for all-cause-free survival and cardiovascular event-free survival, respectively). However, in non-metabolic abnormalities group, the survival probability was not different among BMI categories.

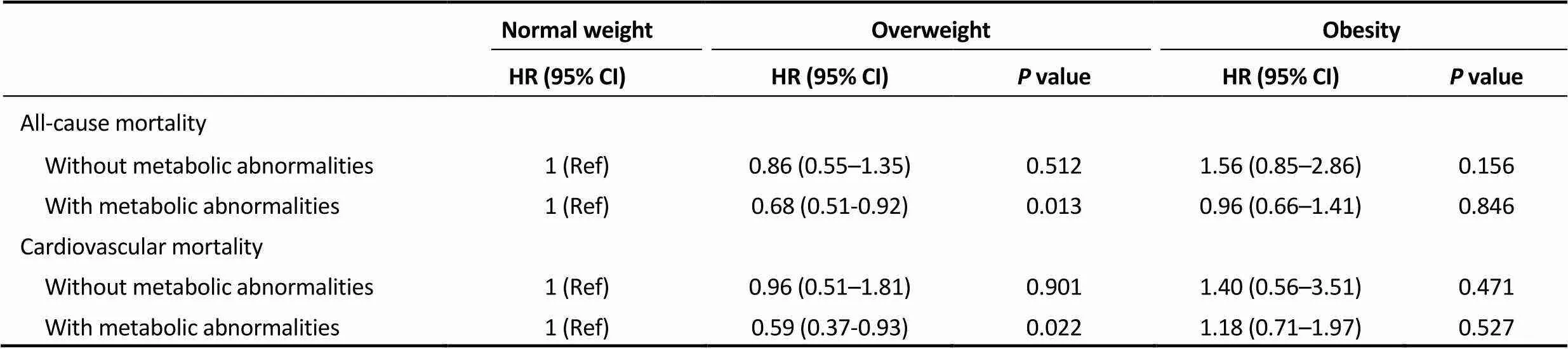

Multivariate analyses of associations between BMI and mortality are presented in Table 3. After adjustment for age, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, total and LDL cholesterols, and serum creatinine, HR and 95% CI for all-cause death and cardiovascular death were 0.68 (0.51–0.92) and 0.59 (0.37–0.93), respectively, in overweight older men with metabolic abnormalities (< 0.05 for both), compared to those with normal weight. Furthermore, although associations between obesity and mortality were not significant, it seemed that risks of obesity for all-cause death and cardiovascular death were higher in participants without metabolic abnormalities than in their counterparts with metabolic abnormalities.

Table 2. Prevalence of mortality across BMI categories in older men with or without metabolic abnormalities.

Data are presented as(%) unless other indicated. Direct method of standardization was used. BMI: body mass index.

Figure 2. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of older men. (A): all-cause mortality, the log-rank testvalues were 0.053 and 0.009 in participants without and with metabolic abnormalities, respectively; (B): cardiovascular mortality, the log-rank testvalues were 0.390 and 0.036 in participants without and with metabolic abnormalities, respectively.

Table 3. Death risk across BMI categories in older men with or without metabolic abnormalities.

Age, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and serum creatinine were adjusted. BMI: body mass index.

3.3 Stratified analyses

When participants were stratified by age (60-69, 70-79, and ≥ 80 years) or smoking status, overweight and obesity were not associated with death risk after adjustment for covariates in all subgroups in participants without metabolic abnormalities (Table 4). However, in participants with metabolic abnormalities, the negative association between overweight and mortality risk remained significant in all subgroups stratified by age, the presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, and the number of metabolic abnormalities (< 0.05 for all). Furthermore, obesity also showed a negative association with death risk in participants with metabolic abnormalities but without hypertension [HR (95% CI): 0.14 (0.03-0.73)].

4 Discussion

Our present study found that the effect of overweight on outcomes was different between older adults without metabolic abnormalities and those with established metabolic abnormalities. Overweight reduced death risk in older men with metabolic abnormalities but not in older men without metabolic abnormalities. Furthermore, obesity did not associated with mortality risk both in older men without metabolic abnormalities and in older men with metabolic abnormalities. The different effect of obesity on mortality between older adults without metabolic abnormalities and those with metabolic abnormalities was not found, which may be partially attributed to the small size of sample in participants with obesity.

Obesity and metabolic abnormalities are common in older adults. Our studies showed that more than half of older men had obesity or metabolic abnormalities. Previous studies reported that both obesity and metabolic abnormalities are independent risk factors of CVD and death.[4,18,19]Based on these reports, recent guidelines encourage population with overweight or obesity to pursue a normal weight and a metabolic health status.[11]However, when obesity and metabolic abnormalities were considered together, the findings are controversial. The literature reported that the population with metabolic abnormalities but normal weight had higher risks for CVD and mortality than the obese population without metabolic abnormalities.[6,7]Our previous study found that associations of obesity with CVD risk were attenuated once one person had metabolic abnormalities.[8]In the present study, the association of obesity with mortality was also attenuated in participants with metabolic abnormalities compared to participants without metabolic abnormalities, although the significant associations were not found in both groups, which may suggest that the adverse effect of obesity on death may be more important in older men without metabolic abnormalities. An explanation for all these findings is that metabolic abnormalities may be closer to CVD and death than obesity. Nearly half to three-quarters of excess risk of obesity for mortality could be mediated by the control of metabolic abnormalities.[5]

Table 4. Stratified analyses of all-cause mortality risk across BMI categories in older men with or without metabolic abnormalities.

Data were shown as HR (95% CI). Age, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and serum creatinine were adjusted. The covariate was not included in models when the participants were stratified by this covariate. LDL: low-density lipoprotein.

Furthermore, the findings of the adverse effects of obesity on outcomes which have been reported in the general population are also controversial in the population with established disease.[3,12]Recent studies reported that obesity had a protective effect on mortality in participants with diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease.[13,14]Our study was the first to observe a protective effect of overweight on death in older men with metabolic abnormalities but not in those without metabolic abnormalities. We suppose that this difference may be also significant in participants with obesity if the size of sample is large enough. Reasons for the different effects of overweight on mortality between the general population and the population with established diseases remain unclear. An attenuation of the adverse effect of obesity in the population with established diseases may be one reason.[5]Furthermore, a shift toward decreased muscle mass and increased fat mass occurs with aging.[20]The protective effects of overweight and moderate obesity, such as nutritional reserve and stores of lean less, may prevail over their adverse effects in older adults. Unfortunately, the percentage of participants with severe obesity was low in our study population; thus, the association between severe obesity and mortality could not be assessed. We think that compared to overweight and mild obesity, severe obesity may significantly increase adverse outcome risks regardless of metabolic abnormalities, contributing to the harmful effect of adipocyte hypertrophy on health outcomes.[21]Finally, we could not exclude a reason that overweight or obese participants may receive more medical care than the participants with normal weight during the follow-up.[22,23]This phenomenon may be more common in those with obesity and metabolic abnormalities co-existed, which caused to a better prognosis in these participants.

The present study has several limitations. First, the size of sample was relatively small in participants with obesity, which may be the reason for the insignificant difference in the effect of obesity on outcomes between the non-metabolic abnormalities and the metabolic abnormalities groups. Using large-scale populations, previous studies reported that obesity increased mortality risk in the general population but decreased mortality risk in the populations with established diseases.[4,14]Second, other indicators of adiposity, such as waist circumference and body fat percentage, were not obtained in our study. Although BMI is widely used to indicate obesity and predict obese-related diseases and mortality, a number of studied reported that waist circumference or body fat percentages were better to reflect body fat distribution and predict prognosis.[24,25]

In conclusion, the present study found that overweight had a protective effect on mortality in older men with metabolic abnormalities but not in those without metabolic abnormalities. Furthermore, obesity was not associated with mortality risk regardless of metabolic abnormalities. These findings suggest that the recommendation of pursuing a normal weight may be wrong in overweight or obese older men, especially for those with metabolic abnormalities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the participants for their contributions.This study was supported by the Military HealthcareProgram (No. 16BJZ40). The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

1 Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome update.2016; 26: 364–373.

2 Han TS, Lean ME. A clinical perspective of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease.2016; 5: 2048004016633371.

3 Ortega FB, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular disease.2016; 118: 1752–1770.

4 The Global BMI Mortality Collaboration. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents.2016; 388: 776–786.

5 Global burden of metabolic risk factors for chronic diseases Collaboration (BMI Mediated Effects); Lu Y, Hajifathalian K,. Metabolic mediators of the effects of body- mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1.8 million participants.2014; 383: 970–983.

6 Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality.2012; 97: 2482–2488.

7 Calori G, Lattuada G, Piemonti L,. Prevalence, metabolic features, and prognosis of metabolically healthy obese Italian individuals: the Cremona Study.2011; 34: 210–215.

8 Zeng Q, Dong SY, Wang ML,. Obesity and novel cardiovascular markers in a population without diabetes and cardiovascular disease in China.2016; 91: 62–69.

9 Collaborators GBDO, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH,. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years.2017; 377: 13–27.

10 Caleyachetty R, Thomas GN, Toulis KA,. Metabolically healthy obese and incident cardiovascular disease events among 3.5 million men and women.2017; 70: 1429–1437.

11 Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H,. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts).2012; 33: 1635–1701.

12 Akin I, Nienaber CA. "Obesity paradox" in coronary artery disease.2015; 7:603–608.

13 Artham SM, Lavie CJ, Milani RV,. Obesity and hypertension, heart failure, and coronary heart disease-risk factor, paradox, and recommendations for weight loss.2009; 9: 124–132.

14 Zhao W, Katzmarzyk PT, Horswell R,. Body mass index and the risk of all-cause mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.2014; 130: 2143–2151.

15 Chang AM, Halter JB. Aging and insulin secretion.2003; 284: E7-E12.

16 Zhou BF; Cooperative Meta-Analysis Group of the Working Group on Obesity in China. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults--study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults.2002; 15: 83–96.

17 Joint Committee for Developing Chinese Guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Adults. Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults (the 2016 revision).2016; 44: 833–853.

18 Lassale C, Tzoulaki I, Moons KGM,. Separate and combined associations of obesity and metabolic health with coronary heart disease: a pan-European case-cohort analysis.2018; 39: 397–406.

19 Fan J, Song Y, Chen Y,. Combined effect of obesity and cardio-metabolic abnormality on the risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.2013; 168: 4761–4768.

20 Weinheimer EM, Sands LP, Campbell WW. A systematic review of the separate and combined effects of energy restriction and exercise on fat-free mass in middle-aged and older adults: implications for sarcopenic obesity.2010; 68: 375–388.

21 Forsythe LK, Wallace JM, Livingstone MB. Obesity and inflammation: the effects of weight loss.2008; 21: 117–133.

22 Harris JA, Byhoff E, Perumalswami CR,. The relationship of obesity to hospice use and expenditures: a cohort study.2017; 166: 381–389.

23 Kosuge M, Kimura K, Kojima S,. Impact of body mass index on in-hospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction.2008; 72: 521–525.

24 Zeng Q, Dong SY, Sun XN,. Percent body fat is a better predictor of cardiovascular risk factors than body mass index.2012; 45: 591–600.

25 Padwal R, Leslie WD, Lix LM,. Relationship among body fat percentage, body mass index, and all-cause mortality: a cohort study.2016; 164: 532–541.

Qiang ZENG, Health Management Institute, Chinese PLA General Hospital, 28 Fuxing Road, Beijing 100853, China. E-mail: zq301@126.com

Telephone: +86-10-68295751

Fax: +86-10-68295928

November 27, 2017

February 22, 2018

March 20, 2018

June 28, 2018

*The first two authors contributed equally to this study.

杂志排行

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- “Malignant” right coronary artery presenting as an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction—a case report

- Influenza vaccination in acute coronary syndromes patients in Thailand: the cost-effectiveness analysis of the prevention for cardiovascular events and pneumonia

- The trend of change in catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for the management of atrial fibrillation over time: a meta-analysis and meta-regression

- Early mortality and safety after transcatheter aortic valve replacement using the SAPIEN 3 in nonagenarians

- Depression and chronic heart failure in the elderly: an intriguing relationship

- CIED implantation in elderly patients: a single-center experience