Understanding cultures beyond medicine

2017-12-21ShengLiu

Sheng Liu

1. MetroHealth Broadway Health Center, 6835 Broadway Ave, Cleveland, OH, USA

Understanding cultures beyond medicine

Sheng Liu1

1. MetroHealth Broadway Health Center, 6835 Broadway Ave, Cleveland, OH, USA

A patient with a terminal illness died of a horrible suicidal attempt and the case provoked deeper learning of how a certain cultural background can lead people to different behaviors. This case study is intended to stimulate more cultural competency—related discussions.

Cultural competency; power distance; context; individualism and collectivism;uncertainty avoidance

My patient’s story

My patient was a 47-year-old man who was the main breadwinner of the family. He was the father of two small children, and a husband.He owned a car, a house, and a small take-out restaurant. He had been healthy until he developed a small mildly painful lump on the right side of his face. It was treated as focal cellulitis without much improvement. Two months later he returned with worsening pain, and subsequently he underwent facial CT, which showed a tumor eroded into the right maxillary sinus.He had a biopsy, which showed low-grade malignancy. It was decided he should undergo surgery in 1 month.

He was extremely anxious about waiting that long. The right side of his face was more painful than ever. He had talked to his friends,relatives, friends of his friends, and relatives of his relatives. All were telling him that he should transfer his care to a different, larger hospital.He decided to transfer his care to the hospital his friends and relatives had told him about, too embarrassed to consult me about his decision.He had been my patient for at least 5 years,and he felt some sense of betrayal in leaving me to go to a different hospital.

The workup started again, and because of the rare type of his tumor, he was taken to the operating room 3 months later, far beyond the time frame my hospital gave him.

In the operating room the cancer was found to have spread deeper into his maxillary sinus and had invaded the bottom of his right eye. So he had to undergo a second surgical procedure, from which he woke up and found he had lost his right eye.

Things did not go the right way for him.He had multiple rounds of chemotherapy,from which he lost muscle, hair, his health,his restaurant, and most of what the family owned, besides the house. The family experienced major financial difficulties, but continued to commit to more treatments with chemotherapy. The hospital social worker was helping with financial issues.

I was kept in the loop remotely via some progress notes from mails that the hospital social worker sent me. I knew the patient was not doing well. A few words were noticeably repeatedly written in those reports saying “the couple (patient and his wife) were very pleasant and cooperative, they indicated their understanding by nodding their agreement.”

Finally, his wife showed up in my office, requesting help.She reported that he had withdrawn from all his relatives and friends, stopped eating, and lost so much weight that he was virtually a skeleton. Hospice care was suggested by his treating hospital, but he declined. She requested he return to me for the rest of his care, and left with the task of bringing him back to my office as soon as he was discharged from the hospital.

She returned alone in a couple of weeks, sobbing.Apparently he had been discharged from the hospital and not to a hospice, but had changed his code status to do not resuscitate. Just a few days after coming home, when their children were at school, he sent her to the store to run his errands. She got a call from her neighbor when she was at the store — her house was on fire. She rushed home and found a severely damaged house, but the most burned of all was her husband’s body.The evidence showed that he was the source of the fire. He took along with his own life, the family’s only asset — the house.

He was dead. The family was in mourning for sometime,but life moved on. As his former physician, I was left with a heart-wrenching question that required soul-searching: what had gone wrong?

My question

This was a patient who spoke conversational English, with Chinese being his native language. Did he truly understand his disease course and treatment options? Why was his depression unrecognized? What was spoken but more importantly what was unspoken but should have been said? What was in his cultural background and mine too that should have been noticed but went unrecognized?

As a clinician, I counsel people all the time. Do I pay attention to the communications and everything that comes with the communication needs? The tone, touch, eye contacts, posture, and nonverbal cues. I know what I say, but do I know what my patients are saying? I took a deeper dive into cultural study, which might give me a clue to explain his behaviors. I would like to understand his integrated patterns of behaviors and his values and beliefs.

Cultural theories

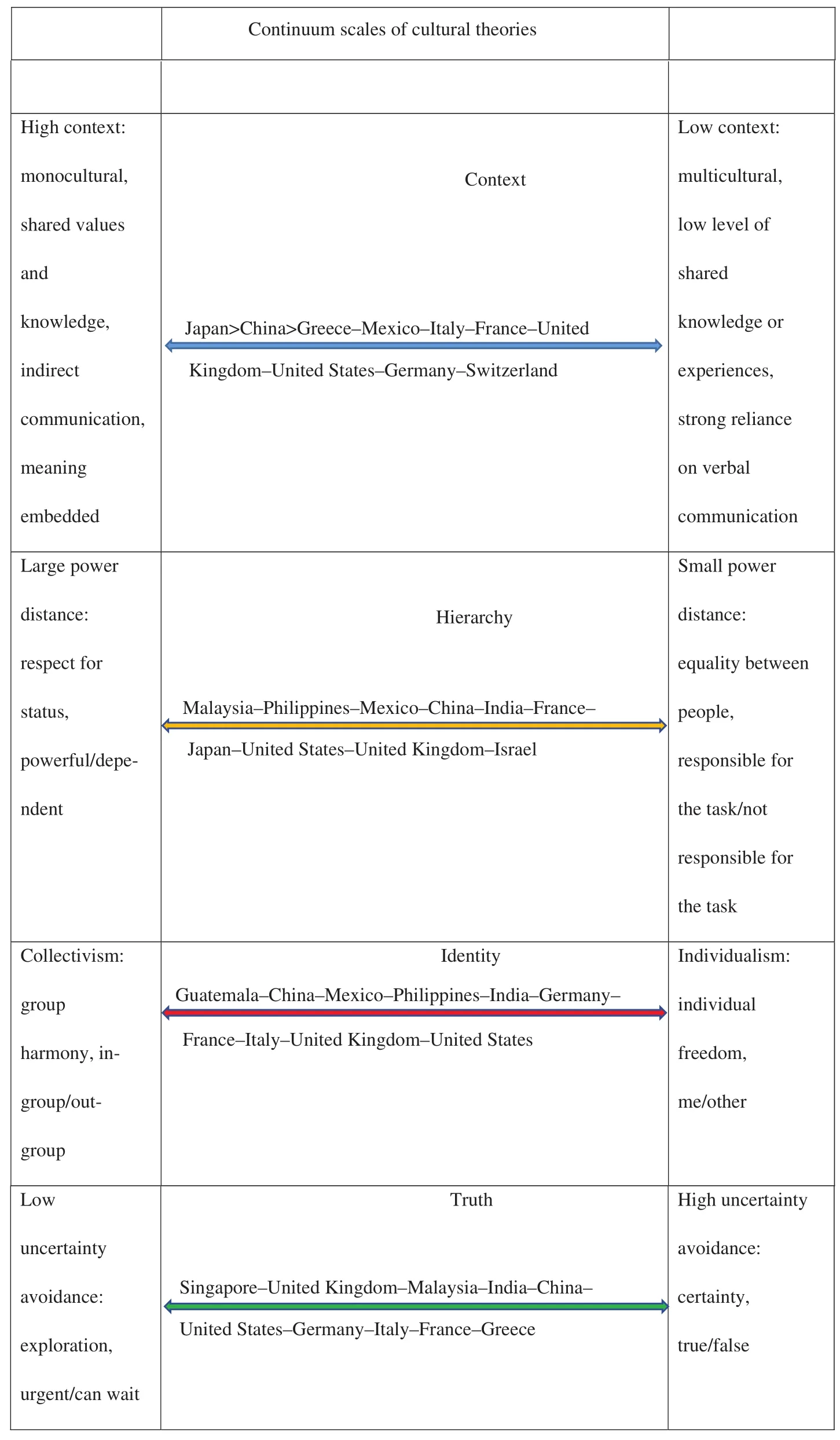

I learned a few concepts to better understand my patient (see Fig. 1). These are high versus low context [1], power distance[2], individualism versus collectivism [2], and high versus low uncertainty avoidance [2].

Context[1] refers to the physical and interpersonal environment, the immediate social situation, and the culture in which communication occurs. All cultures in the world can be placed somewhere on a continuum ranging from high to low context. In high-context cultures, most of the meaning during communication comes from information built into the context. These are unspoken messages. Thus the meaning is inherent and embedded in the context more than in the language. Communication is indirect, and words are secondary.In high-context culture, persuasion is indirect, spiral, illogical,and does not have to be based on evidence. On the other hand,persuasive style in a low-context culture is generally direct,logical, and based on evidence.

Power distance[2] says how power is distributed among people in a particular culture, from small to large. Large power distance cultures believe that some people are superior to others. These cultures believe that each person has a rightful and protected place in the social order. The core value is respect for status, and the core distinction is powerful versus dependent. They believe the actions of authorities should not be challenged or questioned. They believe that hierarchy and inequality are appropriate and beneficial.

Individualism versus collectivism[2] is about whether the individual or the group is favored. People in highly collectivistic cultures value a group orientation and have a strong sense of belonging. They require loyalty to the group,which can include the extended family or a group bonded by a shared goal. The core value is group harmony, and the core distinction is in-group versus out-group. As the individual is expected to place the group over the self, the group is expected to look out for and take care of its individual members.

Fig. 1. Continuum scales of cultural theories (in order of the categories) [1—3].

Uncertainty avoidance[2] addresses how members of a culture adapt to change and cope with uncertainties, ranging from high to low uncertainty avoidance. Cultures differ in the extent to which they can tolerate ambiguity/uncertainty and in the means they select for coping with change. Low uncertainty avoidance cultures have a high tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. There is a tendency to avoid setting rigid rules and laws but to resolve any conflict that might arise. They believe in taking risks and trying new things.

Conclusion

In my patient’s high-context culture, he viewed the discussion of hospice care as a form of unspoken abandonment. Being in a large power distance culture, he was not conditioned to challenge the authority in the large health institution. His only choice seemed to be agreeing with what he was offered and not uttering a word of disagreement. Nodding is a gesture of politeness but was mistaken as an indication of understanding. Because of his collectivism and low level of tolerance to uncertainty, he followed the advice from his circle of family and friends of the same ethnicity and transferred his care to an entirely unfamiliar health system, which ultimately led to delay instead of expedition of his care.

My mind came to rest when I understood why he had made his decision and what had led to his disturbing endof-life path.

May his soul be at peace.

Conflict of interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

1. Hall ET. Beyond culture. 1st ed. New York: Anchor Books;1976.

2. Hofstede GJ, Pedersen PB, Hofstede G. Exploring culture. 1st ed.Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press Inc.; 2002.

3. Cleary Cultural. Geert Hofstede cultural dimensions. 2004-2007.[accessed 2017 July 12]. Available from: //www.clearlycultural.com/geert-hofstede-cultural-dimensions/.

Sheng Liu, MD

MetroHealth Broadway Health Center, 6835 Broadway Ave,Cleveland, OH 44104, USA

Tel.: +1-216-9571650

E-mail: Sliu@metrohealth.org

23 April 2017;

Accepted 11 July 2017

杂志排行

Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Health is primary

- Assessing the accuracy of patient report of the 5As (ask, assess,advise, assist, and arrange) for smoking cessation counseling

- Mental health problems due to community violence exposure in a small urban setting

- Burden of road traffic accidents in Nepal by calculating disability- adjusted life years

- Effect of an educational intervention and parental vaccine refusal forms on childhood vaccination rates in a clinic with a large Somali population

- Tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy use among racial/ethnic minorities in the United States: Considerations for primary care