并发消化道出血的先天性门体分流畸形8例影像学特征病例系列报告

2017-12-02吴先胜乔中伟

季 敏 吴先胜 龚 英 杨 宾 乔中伟

并发消化道出血的先天性门体分流畸形8例影像学特征病例系列报告

季 敏1吴先胜2龚 英1杨 宾1乔中伟1

目的 探讨合并消化道出血的先天性门体分流畸形的影像学特征,以提高对该畸形的认识。方法 纳入复旦大学附属儿科医院病历系统中先天性门体分流且病史中有消化道出血症状的病例,采集性别、年龄、临床表现、CTA和MRA影像学资料、外科手术结局。CTA为GE Light speed 64排螺旋CT扫描仪,MRA为Siemens Avanto 1.5 T 扫描仪,提取纳入病例的CTA原始图像,以1.25 mm层厚/0.625 mm层间隔重建,传入后处理工作站进行多平面重建;提取纳入病例的MRA原始图像,传入MR工作站进行后期多平面重建;由2名从事儿科影像诊断10年以上医生独立读片,观察门静脉及其属支的形态及走行,异常门体分流位置、途径,髂静脉、下腔静脉及肠管、肠壁血管分布。结果 2008年3月至2017年1月符合本文病例纳入标准的连续病例8例,男6例,年龄3月至10岁,7例贫血,7例便血,1例呕血。8例均行CTA检查,其中2例同时行MRA检查。截止出院时,6例行手术治疗,2例随访观察。8例先天性门体分流畸形患儿均为肝外型门体分流,2例肝外型Ⅰ型,6例为Ⅱ型。以便血为表现的7例中,髂内静脉、直肠上静脉及结肠静脉扩张扭曲;以呕血为表现的1例,脾静脉和肠系膜上静脉汇合后通过胃冠状静脉汇入左肾静脉,胃冠状静脉显著扩张、扭曲。结论 合并便血的先天性门体分流大部分通过肠系膜下静脉与髂静脉异常沟通,发生便血的比例高。

先天性门体分流; Abernethy畸形; 儿童; 消化道出血; X线计算机体层血管成像,磁共振血管造影

先天性门体分流是一种少见的门静脉畸形,其特征是门静脉与腔静脉之间存在先天性异常沟通,门静脉血全部或部分未入肝脏而直接汇入腔静脉,肝内门静脉可缺如、发育不良或正常[1]。先天性门体分流的临床表现多样,可因肝脏肿瘤、心脏畸形检查偶然发现,也可表现为门体脑病、高氨血症和消化道出血,或者没有任何症状[2-5]。消化道出血是先天性门体分流畸形少见的临床表现[1, 5, 6],临床容易漏诊、误诊,从而延误治疗。本文收集复旦大学附属儿科医院(我院)治疗的临床表现为消化道出血的先天性门体分流畸形的病例,探讨其影像学表现,增强临床认识。

1 方法

1.1 病例纳入标准 我院病历系统中检索先天性门体分流,病史中有消化道出血症状的病例被纳入本文分析。

1.2 病例资料提取 采集性别、年龄、临床表现、CTA和MRA影像学资料和外科手术结局。

1.3 CTA检查 采用GE Light speed 64排螺旋CT扫描仪(美国GE公司)。检查范围从肝顶至盆腔,行CT平扫和增强扫描,增强扫描时间为注射造影剂后50~60 s。扫描参数:80~100 kV,40~70 mAs,层厚5 mm,螺距1.375。增强对比剂使用碘对比剂碘海醇注射液(300 mgI·mL-1,美国GE公司),剂量1.5~2 mL·kg-1,流速视患儿年龄、血管等情况快慢不等,范围0.8~2.0 mL·s-1。对于lt;5岁不合作患儿给予0.5 mL·kg-1的水合氯醛口服或灌肠镇静。

1.4 MRA检查 采用Siemens Avanto 1.5 T扫描仪(德国西门子公司),使用体线圈,选用3D-FLASH序列,自由呼吸状态下扫描,多期扫描获得动脉期、门静脉及静脉期图像。扫描参数:TR/TE3.14/1.29 ms,翻转角25°,带宽450 Hz/pixel,扫描野262 mm×400 mm,矩阵227×384,层厚1.5 mm,单期采集时间15 s。增强对比剂使用钆双胺注射液(0.5 mmol·mL-1,美国GE公司),剂量0.1 mmol·kg-1。对于lt;5岁不合作患儿给予0.5 mL·kg-1水合氯醛口服或灌肠镇静。

1.5 图像分析 提取CTA原始图像,以1.25 mm层厚/0.625 mm层间隔重建,传入后处理工作站进行多平面重建;提取MRA原始图像,传入MR工作站进行后期多平面重建;由2名资深儿科放射科医生(从事儿科影像诊断10年以上)独立读片,观察门静脉及其属支的形态及走行,异常门体分流位置、途径,髂静脉、下腔静脉及肠管、肠壁血管分布。

2 结果

2.1 一般资料 2008年3月至2017年1月符合本文病例纳入标准的连续病例8例,其中男6例,年龄3月至10岁,lt;1岁2例,~5岁2例,~10岁3例,gt;10岁1例。表1显示,7例贫血,7例便血,1例呕血。8例均行CTA检查,其中2例同时行MRA检查;5例行结肠镜检查,3例直肠乙状结肠静脉曲张,1例全结肠静脉曲张,1例直肠静脉曲张;1例行DSA检查。截止出院时,6例行手术治疗,其中4例接受Soave术结合Sarasola-Klose内痔环切术,1例接受胃底静脉断流、脾肾静脉分流术,1例接受肠系膜下静脉手术结扎术;2例随访观察。

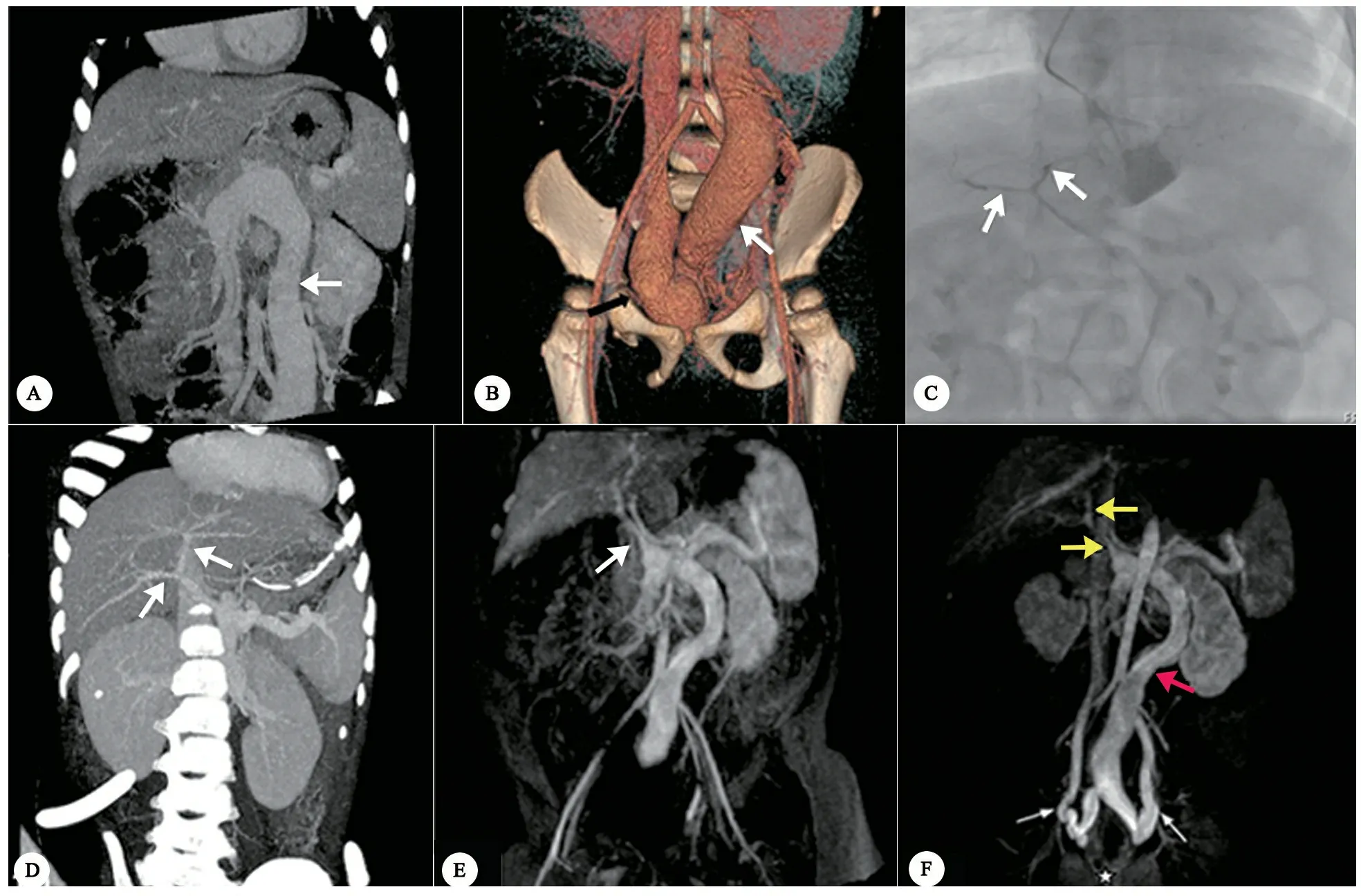

2.2 CTA/MRA影像学表现 8例先天性门体分流畸形患儿均为肝外型门体分流,2例(例1和3)为Ⅰ型,余6例为Ⅱ型。以便血为表现的7例中,髂内静脉、直肠上静脉及结肠静脉扩张扭曲,其中例1和3脾静脉和肠系膜上静脉汇合成共干后汇入髂内静脉,门静脉主干及肝内门静脉缺如;例4、5、7和8脾静脉和肠系膜上静脉汇合成共干后汇入髂内静脉,门静脉主干、肝内门静脉纤细(图1);例6交通支起自脾静脉,汇入髂内静脉,门静脉主干及肝内门静脉形态正常。以呕血为表现的例2,脾静脉和肠系膜上静脉汇合后通过胃冠状静脉汇入左肾静脉,胃冠状静脉显著扩张、扭曲(图2)。

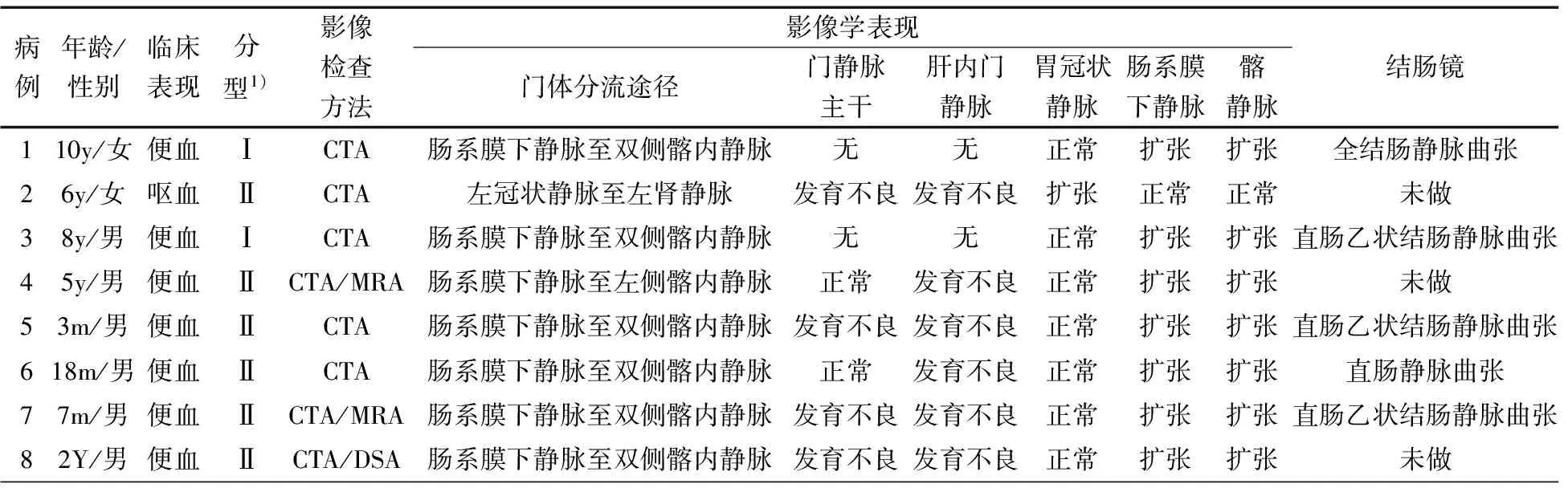

表1 8例患儿的一般资料及影像学表现

注 y:岁;m:月;1):肝外型

图1以便血为表现的门体分流病例影像学特征

注 图A~D为例8,2岁男孩,便血。 A:CTA,冠状位MIP图像示异常粗大的共干(箭头),肝内门静脉及门静脉主干未显影。B:CTA,冠状位VR图像示共干汇入右侧髂内静脉(箭头)。C:DSA造影示发育不良肝内门静脉和门静脉主干(箭头)。D:接受肠系膜下静脉结扎术后,CTA 图像示发育不良的肝内门静脉及门脉主干显影(箭头)。图E和F为例7,7个月男孩,便血。E:MRA,冠状位图像示发育不良门静脉主干(箭头)。F:MRA,冠状位图像示异常扩张的肠系膜下静脉(红箭头)起源于脾静脉和肠系膜上静脉共干,汇入双侧髂内静脉;直肠静脉扩张(白箭头)。门静脉主干和肝内门静脉发育不良(黄箭头)

图2以呕血为表现的门体分流病例影像学特征

注 例2,6岁女孩,呕血。A:CTA,冠状位图像示异常扩张的胃冠状静脉(红箭头)起源于脾静脉和肠系膜上静脉共干;门静脉主干和肝内门静脉发育不良(白箭头)。B和C:横断位和斜矢状位图像示异常扩张的胃冠状静脉(白箭头),汇入左肾静脉(图C红箭头)

3 讨论

先天性门体分流是由于胚胎期脐静脉和卵黄静脉发育异常,导致门静脉与腔静脉之间异常分流所形成的先天畸形,是由Abernethy在1793年对1例死因不明的10月龄女婴尸体解剖时首次发现[7]。至今为止,有多位学者对先天性门体分流提出了不同的分类方法[5, 8-10]。先天性门体分流的传统分型为肝外型(Ⅰ和Ⅱ型)[9]和肝内型(Ⅰ~Ⅳ型)[10]。肝外型Ⅰ 型即肝脏完全无门静脉血灌注,肝内门静脉缺如,全部的门静脉血汇入腔静脉;肝外型Ⅱ型即肝脏有门静脉血灌注,部分门静脉血汇入腔静脉。Kobayashi[5]则根据异常交通汇入处将肝外型门体分流分为3型,肝外型A汇入下腔静脉,肝外型B汇入肾静脉,肝外型C汇入髂静脉。本文8例均为肝外型门体分流,其中2例为肝外型Ⅰ型,6例为肝外型Ⅱ型。按Kobayashi的分类方法,7例为肝外型C(本文例1、3~8),1例为肝外型 B(本文例2)。

先天性门体分流临床表现多变,不具特异性。有文献综述了[4]316例先天性门体分流常见的伴发症为先天性心脏畸形(22%)、肝脏肿瘤(26%)、肺性高血压或肝肺综合征(18%)、高氨血症/精神异常(35%)。Kobayashi[5]报告,8.1%肝外门体分流表现为消化道出血,同时显示肝脏肿瘤的发生率在肝外型Ⅰ 型中明显高于肝外型Ⅱ 型,心脏畸形、门体脑病、消化道出血在这两型中无明显差异[5]。

并发便血的门体分流病例中,绝大部分异常交通通过肠系膜下静脉汇入髂静脉,Kobayashi 等将这一类分为肝外型 C[5]。这种类型门体分流并不多见,但便血的发生率显著升高[5]。本文病例中有7例表现为便血,门体分流均通过肠系膜下静脉汇入髂静脉。 国外对于门体分流并发便血的报道很少,仅在Pubmed检索到8篇9例[6, 8, 11-17]。 8/9例为肝外型门体分流,其中7例为肝外型Ⅰ型,1例为Ⅱ型[6, 8, 12-17];门体异常交通支均经肠系膜下静脉汇入髂内静脉,其中2例汇入双侧髂内静脉,2例汇入左侧髂内静脉,2例汇入右侧髂内静脉,2例文献中未提及确切汇入静脉[6, 8, 12-17]。国内多为个例报告并发便血的门体分流病例。王亚梅 等[18]综述分析了2001年至2012年国内报道的18例门体分流病例,5例表现为便血的病例中,4例为肝外型Ⅰ 型,1例为Ⅱ型,均通过肠系膜下静脉与腔静脉异常交通,其中2例汇入右髂内静脉,1例汇入双侧髂内静脉,1例汇入髂静脉,1例与盆腔静脉丛交通。直结肠周围广泛的侧枝通过直肠静脉丛(直肠上静脉)进一步连接了肠系膜下静脉和髂静脉[12]。这些侧枝静脉的曲张、破裂可能是引起便血的原因[6]。但Arana认为肠系膜下静脉-髂静脉侧枝循环发生的机制尚不完全清楚[12]。

虽然绝大多数的便血患儿都是通过肠系膜下静脉汇入至腔静脉,但也有例外。 Alomari等[11]报告1例临床表现为便血的静脉导管未闭的病例。肠镜检查显示小肠黏膜异常,手术切除病变肠段后便血症状依旧存在,直至堵闭了静脉导管后便血症状消失,推测未闭的静脉导管像“泵”一样分流了一部分肠系膜的血流,从而造成肠黏膜缺血、糜烂,导致肠道出血。病变肠段病理检查亦证实其肠壁黏膜没有静脉曲张表现。

先天性门体分流并发呕血的病例罕见,国内有文献[19]报告1例17岁男孩,突发呕血,发现肝内门静脉缺如,胃冠状静脉经胃底贲门静脉丛到达食管上段后汇入奇静脉,食管胃底静脉明显曲张。本文例2亦表现为呕血,CTA检查显示脾静脉和肠系膜上静脉形成共干后经胃冠状静脉汇入左肾静脉,胃冠状静脉显著扩张、扭曲。术中证实该患儿无肝硬化,门静脉压20 mmHg,不伴食道静脉曲张,与由肝硬化、门脉高压引起的食道、胃底静脉曲张表现不同。综合2例以呕血为表现的患儿影像学特点,其门静脉血均通过胃冠状静脉与腔静脉异常沟通。

先天性门体分流会导致一些严重的并发症,如肺动脉高压、肺肝综合征、肝性脑病和肝脏肿瘤等。堵闭分流不仅可以避免并发症的发生,并且可以使已经出现的并发症逆转、消失[20-22]。目前认为2岁以内的、小的肝内门体分流有自我关闭的可能,故2岁以内患儿可以随访观察;2岁以后的门体分流建议积极堵闭[22]。有学者认为肝外型Ⅰ 型由于肝内门静脉缺如,肝移植是其唯一的治疗方法[23]。目前发现,肝外型Ⅰ型门体分流并非真正的肝内门静脉缺如,虽然在CTA/MRA上没有显示、甚至在血管造影时也没有显影的发育不全的肝内门静脉,但如果在血管造影时进行试验性堵闭分流后,那些细小的血管可以显影[20-22]。临床治疗也发现,堵闭分流后发育不良的门静脉和/或分支可以逐渐发育、增粗,推测肝内门静脉分支的再生可能通过胆管周围的血管丛[22]。如果这些结果得到证实,肝移植将不再是肝外型Ⅰ型的唯一治疗方法[21, 22],肝外型Ⅱ型分流和gt;2岁的肝内分流可以通过腹腔镜或开放手术结扎、堵闭,或经导管栓塞治疗[24, 25]。通过肝脏移植[13]、外科手术结扎[16]、导管栓塞治疗[11]成功治疗并发便血的门体分流病例均有报道。本文4例接受Soave术结合Sarasola-Klose内痔环切术[26],1例接受胃底静脉断流、脾肾静脉分流术,1例接受外科手术结扎术。

早期发现、及时治疗对于先天性门体分流患者的预后至关重要。超声检查具有简易、无创、非电离辐射等优点,可作为先天性门体分流的筛查方法;但超声检查可能会因为新生儿和婴幼儿胃肠道气体的干扰,漏诊肝外分流[1]。CTA和MRA检查不仅可以清晰显示分流和腹腔血管,同时可以观察腹腔实质性脏器病变及其他合并的畸形[6]。与CTA相比,MRA检查因其无辐射性更适合儿童患者。血管造影对于显示在CTA和MRA上无法显示的发育不全的肝内门静脉有优势,同时它可以进行栓塞治疗。

综上所述,消化道出血是先天性门体分流少见的临床表现。表现为便血的先天性门体分流患儿其门静脉血绝大部分通过肠系膜下静脉与髂静脉异常沟通,继而汇入下腔静脉;这一类型门体分流并不常见,但发生便血的比例相当高,应引起重视。而门体分流患儿中通过胃冠状静脉与腔静脉异常沟通者,可有呕血表现。CTA/MRA检查对于发现、诊断先天性门体分流及对其进一步分类中有着巨大价值和优势。

[1] Guerin F, Blanc T, Gauthier F, et al. Congenital portosystemic vascular malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg, 2012, 21(3): 233-244

[2] Alonso-Gamarra E, Parron M, Perez A, et al. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts: a comprehensive review. Radiographics, 2011, 31(3): 707-722

[3] Mcelhinney DB, Marx GR, Newburger JW. Congenital portosystemic venous connections and other abdominal venous abnormalities in patients with polysplenia and functionally univentricular heart disease: a case series and literature review. Congenit Heart Dis, 2011, 6(1): 28-40

[4] Sokollik C, Bandsma RH, Gana JC, et al. Congenital portosystemic shunt: characterization of a multisystem disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2013, 56(6): 675-681

[5] Kobayashi N, Niwa T, Kirikoshi H, et al. Clinical classification of congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatol Res, 2010, 40(6): 585-593

[6] Niwa T, Aida N, Tachibana K, et al. Congenital absence of the portal vein: clinical and radiologic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr, 2002, 26(5): 681-686

[7] Abernethy J, Banks J. Account of two instances of uncommon formation, in the viscera of the human body. Bart. P. R. S. Philos Trans R Soc Lond, 1793, 83: 59-66

[8] Lautz TB, Tantemsapya N, Rowell E, et al. Management and classification of type Ⅱ congenital portosystemic shunts. J Pediatr Surg, 2011, 46(2): 308-314

[9] Morgan G, Superina R. Congenital absence of the portal vein: two cases and a proposed classification system for portasystemic vascular anomalies. J Pediatr Surg, 1994, 29(9): 1239-1241

[10] Park JH, Cha SH, Han JK, et al. Intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 1990, 155(3): 527-528

[11] Alomari AI, Chaudry G, Fox VL, et al. Atypical manifestation of patent ductus venosus in a child: intervening against a paradoxical presentation. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2009, 20(4): 537-542

[12] Arana E, Marti-Bonmati L, Martinez V, et al. Portal vein absence and nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver with giant inferior mesenteric vein. Abdom Imaging, 1997, 22(5): 506-508

[13] Charre L, Roggen F, Lemaire J, et al. Hematochezia and congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt with absent portal vein: successful treatment by liver transplantation. Transplantation, 2004, 78(9): 1404-1406

[14] Gadodia A, Sharma R, Kandpal H, et al. Congenital absence of portal vein with large inferior mesenteric-caval shunt. Trop Gastroenterol, 2011, 32(3): 223-226

[15] Grazioli L, Alberti D, Olivetti L, et al. Congenital absence of portal vein with nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver. Eur Radiol, 2000, 10(5): 820-825

[16] Horiguchi Y, Kitano T, Takagawa H, et al. A large inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the internal iliac vein. Gastroenterol Jpn, 1988, 23(6): 684-687

[17] Komatsu S, Nagino M, Hayakawa N, et al. Congenital absence of portal venous system associated with a large inferior mesenteric-caval shunt: a case report. Hepatogastroenterology, 1995, 42(3): 286-290

[18] 王亚妹, 钟琳, 陶于洪. 2001年至2012年中国18例Abernethy畸形综合报道. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2013, 28(19): 1478-1482

[19] 陈国庭, 李恒平. Abernethy畸形一例. 中华普通外科杂志, 2005, 20(5): 328

[20] Bernard O, Franchi-Abella S, Branchereau S, et al. Congenital portosystemic shunts in children: recognition, evaluation, and management. Semin Liver Dis, 2012, 32(4): 273-287

[21] Blanc T, Guerin F, Franchi-Abella S, et al. Congenital portosystemic shunts in children: a new anatomical classification correlated with surgical strategy. Ann Surg, 2014, 260(1): 188-198

[22] Franchi-Abella S, Branchereau S, Lambert V, et al. Complications of congenital portosystemic shunts in children: therapeutic options and outcomes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2010, 51(3): 322-330

[23] Barsky MF, Rankin RN, Wall WJ, et al. Patent ductus venosus: problems in assessment and management. Can J Surg, 1989, 32(4): 271-275

[24] Bruckheimer E, Dagan T, Atar E, et al. Staged transcatheter treatment of portal hypoplasia and congenital portosystemic shunts in children. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol, 2013, 36(6): 1580-1585

[25] Kim MJ, Ko JS, Seo JK, et al. Clinical features of congenital portosystemic shunt in children. Eur J Pediatr, 2012, 171(2): 395-400

[26] Lv Z, Xiao X, Zheng J, et al. Modified Soave procedure for the treatment of vascular malformations involving anorectum and sigmoid colon. J Pediatr Surg, 2009, 44(12): 2359-2363

2017-08-25

2017-10-12)

(本文编辑:张崇凡)

Imagingfeaturesof8casesofcongenitalportosystemicshuntwithgastrointestinalhemorrhage:Caseseriesreport

JIMin1,WUXian-sheng2,GONGYing1,YANGBin1,QIAOZhong-wei1

(1DepartmentofRadiology,Children'sHospitalofFudanUniversity,Shanghai201102,China; 2DepartmentofRadiology,Children'sHospitalofXiamen,Xiamen361000,China)

GONG Ying, E-mail:gongying77@163.com

ObjectiveTo describe the imaging features of congenital portosystemic shunt presenting in 8 children with gastrointestinal bleeding.MethodsThis retrospective, single-center study was approved by our institutional review board. We searched the cases of congenital portosystemic shunt with history of gastrointestinal bleeding in hospital information system of Children's Hospital of Fudan University. All patients' medical records including sex, age, clinical manifestations, CTA and MRA imaging data, and surgical outcome were reviewed. The raw CT data were reconstructed into 1.25-mm slice thickness and 0.625-mm slice interval, and then were sent into a CT workstation for the post-processing. Also, the raw MR date were sent into an MR workstation for post-processing. After the data were post-processed, all of the images were sent to the Picture Archiving and Communication System and were reviewed by 2 radiologists with more than 10 years experience in pediatric abdominal CT and MR imaging; both radiologists were blinded to the clinical data and identified the main portal vein, intrahepatic portal vein, internal iliac vein and superior rectal vein, as well as the portosystemic shunts. A consensus interpretation of image findings between them was accepted.ResultsA total of 8 consecutive cases with the inclusion criteria were included in this study from March 2008 to January 2017. 6 were male, 2 were female, age was ranged from 3 months to10 years. 7 patients presented with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, 1 with hematochezia, 7 patients with anemia. All patients underwent CTA examination, 2 of them underwent MRA examination at the same time. By the time of discharge, 6 cases

surgical treatment, and 2 cases were followed up. All of the 8 cases were congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt, 6 were type Abernethy Ⅱ and 2 were type Abernethy Ⅰ. The images of the seven patients with hematochezia showed that the shunts were from the splenomesenteric junction (n=6) or splenic vein (n=1) to the internal iliac vein via an inferior mesenteric vein .One patient with hematemesis showed the shunt from the splenomesenteric junction to the left renal vein via the venae coronaria ventriculi.ConclusionMost of congenital portosystemic shunt patients with gastrointestinal bleeding had a shunt that drained portal blood into the iliac vein via an inferior mesenteric vein. This type of shunt was not common in congenital portosystemic shunt, but the prevalence of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with this type was high.

Congenital portosystemic shunt; Abernethy malformation; Child; Gastrointestinal bleeding; Computed tomography angiography; Magnetic resonance angiography

1 复旦大学附属儿科医院放射科 上海,201102;2 厦门市儿科医院放射科 厦门,361000

龚英,E-mail:gongying77@163.com

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2017.05.008