微拟球藻富油藻株筛选及柱状光生物反应器培养评价研究

2017-09-12何文栋朱葆华冯磊力常雅青杨官品潘克厚

何文栋朱葆华冯磊力常雅青杨官品潘克厚,

(1. 海水养殖教育部重点实验室(中国海洋大学), 青岛 266003; 2. 中国海洋大学海洋生命学院, 青岛 266003; 3. 青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室, 海洋渔业科学与食品产出过程功能实验室, 青岛 266003)

微拟球藻富油藻株筛选及柱状光生物反应器培养评价研究

何文栋1朱葆华1冯磊力1常雅青1杨官品2潘克厚1,3

(1. 海水养殖教育部重点实验室(中国海洋大学), 青岛 266003; 2. 中国海洋大学海洋生命学院, 青岛 266003; 3. 青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室, 海洋渔业科学与食品产出过程功能实验室, 青岛 266003)

研究以亲脂性荧光染料BODIPY505/515和流式细胞仪为基础, 从多株诱变海洋微拟球藻(Nannochloropsis oceanica)中筛选到4株候选富油藻株(MT-1,2,3,4), 并利用柱状光生物反应器对诱变株的产油能力进行了综合评价。结果表明, 藻株筛选时最佳BODIPY505/515使用浓度为0.87 μg/mL, 染色时间为10min; 4株诱变株产油性能较野生株有较大提高, 其中MT-4油脂积累达到了干重的66%, 油脂产率比野生型藻株提高了45%, 达到了27.32 mg/(L·d)。4株诱变株的脂肪酸组成合适, 其中C16和C18之和占78%以上, 且主要以饱和脂肪酸和单不饱和脂肪酸为主; 多不饱和脂肪酸只占总脂肪酸的6%—8%, 非常适合生物柴油生产。研究提供了一种针对海洋微拟球藻富油藻株快速、有效的筛选方法, 并以此为基础筛选得到4株极具生物柴油生产潜力的候选藻株, 有望用于规模化生产。

生物柴油; 海洋微拟球藻; BODIPY505/515; 诱变筛选; 柱状光生物反应器

由于化石能源的不可再生性以及其消耗对环境造成的污染, 寻找可再生、清洁型能源势在必行[1]。生物柴油由于其不含硫、闪点高、易储存运输、易降解等优点, 近年来备受关注[2,3]。微藻具备生长快、生物量大、光合作用效率高、油脂含量高等优点而被认为是最具潜力的生物柴油生产原料[4—7]。

微拟球藻(Nannochloropsis)属真眼点藻纲(Eustigmatophyceae), 微拟球藻属, 直径约2—3 μm, 在海水和淡水中均有分布。其生长速度快, 能够在1d内实现生物量倍增, 油脂含量高, 且脂肪酸组成非常适合生物柴油的生产[8,9]。尽管微拟球藻应用潜力巨大, 但以此生产生物柴油的成本仍然很高。降低生物柴油生产成本的方式众多, 选育优良藻株是其中一个重要环节。诱变育种作为一种简单易行的育种策略, 若能结合高效的筛选方法, 将有助于为生物柴油生产提供更多的候选优良藻株, 从而降低生产成本。

BODIPY505/515是一种亲脂性的荧光染料, 能够特异性的与中性脂结合, 具有摩尔消光系数和荧光量子产量高, 发射波谱范围窄, 不受微藻自身荧光干扰等良好的光谱性质[10,11], 可以应用在微藻富油藻株的筛选中。本研究利用BODIPY505/515结合流式细胞仪的方法, 对亚硝基胍(NTG)诱变后的海洋微拟球藻进行筛选, 并在柱状光生物反应器中对筛选得到的4株诱变藻株进行了产油特性验证评价, 旨在提供一种快速、有效筛选富油藻株的方法, 为优良富油藻株的选育提供参考。

1 材料与方法

1.1 藻种及培养方法

野生型海洋微拟球藻(N. oceanica)取自中国海洋大学应用微藻生物学实验室微藻种质库。所有诱变株(共92株)均由原始藻株经NTG诱变后得到。培养条件如下: 光照强度约50 μmol/(m2·s)(日光灯光源); 培养温度(25±1)℃; 光暗周期12h:12h。

1.2 诱变藻株的筛选及柱状光生物反应器验证

诱变藻株培养至平台期初期后, 接种至100 mL锥形瓶中(20 mL培养体系), 起始接种密度为105个细胞/mL。在培养至平台期后, 将所有诱变株的藻细胞浓度调整为106个细胞/mL, 并向其中加入DMSO (终浓度2%), 常温下预处理10min; 经BODIPY505/515染色后, 使用流式细胞仪(激发波长488 nm,发射波长为515 nm)对诱变藻株的荧光值进行测定。染色处理设置如下: 首先, 在基础染色时间定为15min的条件下, 设置不同的BODIPY505/515梯度(0.12、0.37、0.62、0.87、1.12和1.49 μg/mL)以确定最佳染色浓度。然后, 在最佳染色浓度下进一步探讨不同染色时间对结果的影响(5、10、15和20min)。每个样品设置3个重复。

筛选后使用柱式反应器对荧光值最高的4株诱变藻株进行培养, 并对产油表现进行综合评价。反应柱直径6 cm, 培养体积800 mL。培养条件如下:培养温度20—26℃, 光照强度54—90 μmol/(m2·s) (日光灯光源), 光暗周期12h:12h。以CO2和空气的混合气体进行通气培养(CO2体积占比1.5%), 通气速率为200 mL/min。每个藻株设置3个重复。

1.3 生长曲线绘制及比生长速率测定

每天定时取样, 用分光光度计(Hitachi U-3310)测定OD750并绘制生长曲线。比生长率通过公式K=(lnNt–lnN0)/(t1–t0)计算, Nt和N0分别为在时间t1和t0时的吸光值[12]。

1.4 叶绿素含量及PSII最大光能转化效率(Fv/Fm)测定

每天定时取样, 将藻液稀释至适当浓度, 暗适应15min后, 使用Water-PAM水样叶绿素荧光仪(Walz, Germany)测定Fv/Fm。叶绿素a使用甲醇进行提取, 并通过公式u=13.43A665v/(lV)计算[13], v为藻液体积(mL), V为甲醇体积(mL), l为测量光程(cm)。

1.5 总脂和油脂产率

总脂使用重量法进行测定, 具体步骤参照文献[14, 15]。油脂产率通过公式PL=PDMDW×LW计算[16]。PDMDW代表生物量产率, LW为总脂含量(%, 占干重百分比)。

1.6 甘油三酯(TAG)分析

甘油三酯分析采用薄层层析法[17]进行。将TAG标准品和样品滴加至硅胶板, 样品量为2 μL,展层剂体系为正己烷:乙醚:乙酸=70:30:1。将点好样的硅胶板置于展缸中无展层液的一侧, 5min后待挥发的展层液浸润硅胶板后, 将展层液倾斜至展缸另一侧。展层后将层析板置于通风橱内吹干, 然后放入含少量碘粒的烧杯中, 37℃恒温显色5— 10min, 三酰甘油标准品为美国Sigma产品(Glyceryl trioleate T7140-500MG), 所用硅胶板为TCL Silica gel 60 F254(Merck Millipore)。

1.7 脂肪酸组成

脂肪酸测定使用气相色谱法, 具体参考文献[15, 18]。

1.8 数据分析

采用软件SPSS16.0进行单因素方差分析(ANOVA),并进行多重比较(LSD), 显著水平为P<0.05。

2 结果

2.1 最佳筛选条件

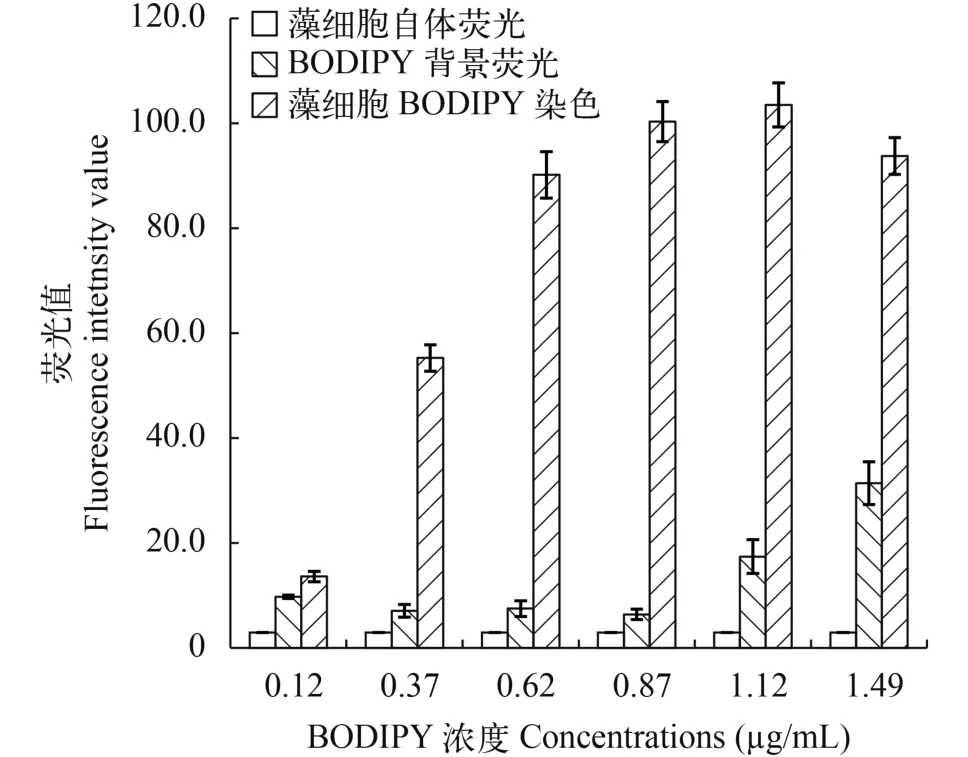

由图 1可以看出, 在BODIPY505/515浓度为0.12—1.12 μg/mL时, 藻细胞荧光强度随BODIPY505/515浓度的增加而增加; 而当浓度继续增加至1.49 μg/mL时, 藻细胞荧光值反而有所降低。另外, 在BODIPY505/515浓度达到1.12 μg/mL后, 其背景荧光值开始急剧增加。从实验的准确性及经济性考虑, 最终确定BODIPY505/515的最佳使用浓度为0.87 μg/mL。

图 1 不同BODIPY浓度下藻细胞自发荧光, BIDIPY背景荧光和藻细胞染色后荧光值Fig. 1 Microalgae autofluorescence, BODIPY505/515autofluorescence and fluorescence of microalgae stained by different concentrations of BODIPY505/515

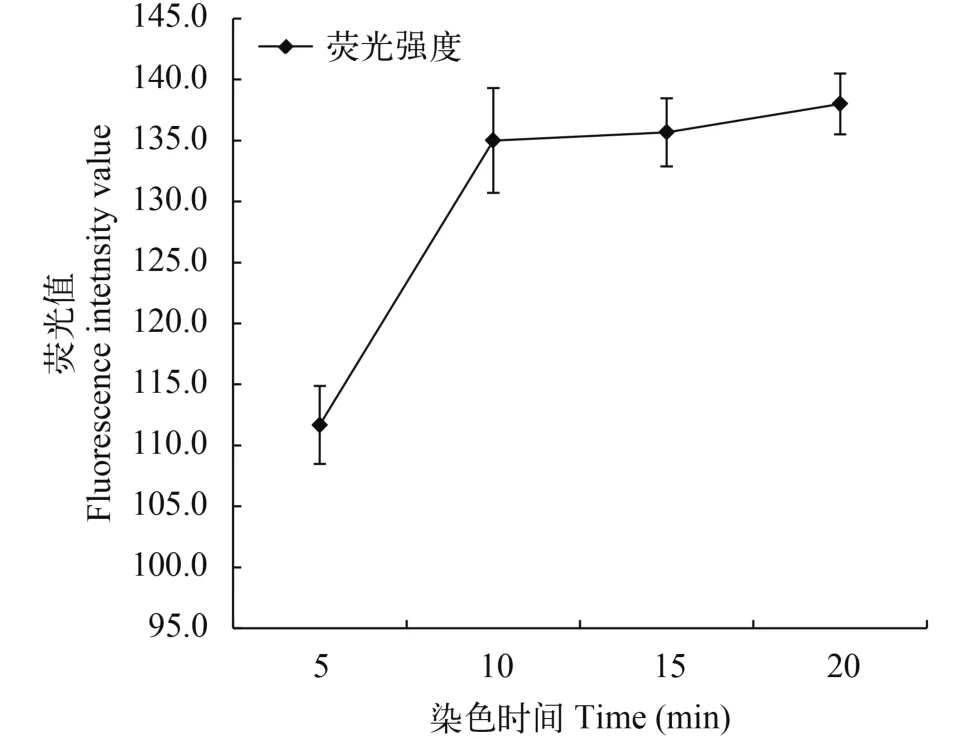

由图 2可以看出, 藻细胞经BODIPY505/515染色后, 在5—10min时, 荧光值随染色时间的增加而升高; 染色时间达到10min后, 藻细胞荧光值基本稳定。因此, 本实验确定的针对海洋微拟球藻富油藻株的最佳筛选条件为: BODIPY505/515浓度为0.87 μg/ mL, 染色时间10min。

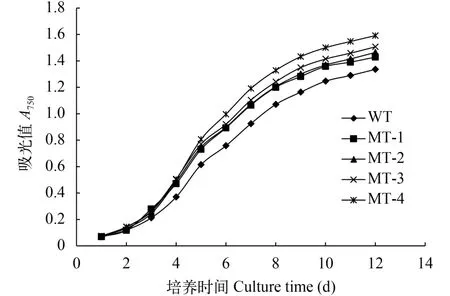

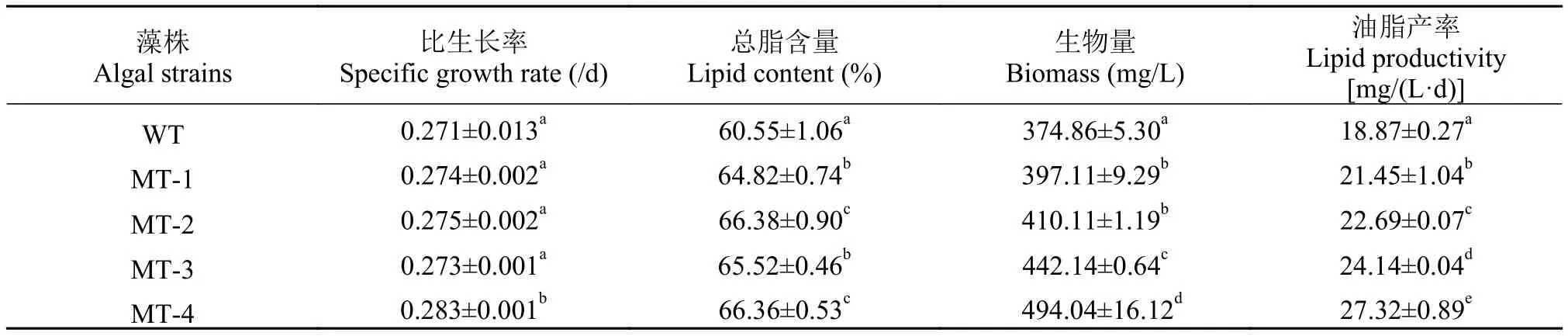

2.2 诱变藻株生长情况和生物量

由图 3和表 1可以看出, 野生型藻株与诱变藻株(MT-1、MT-2、MT-3、MT-4)生长趋势一致, 但诱变藻株的生长速率高于野生型藻株。MT-1、MT-2、MT-3、MT-4的终生物量分别为397.11、410.11、442.14和494.04 mg/L, 均显著高于野生型藻株。

图 2 BODIPY染色时间对海洋微拟球藻荧光值的影响

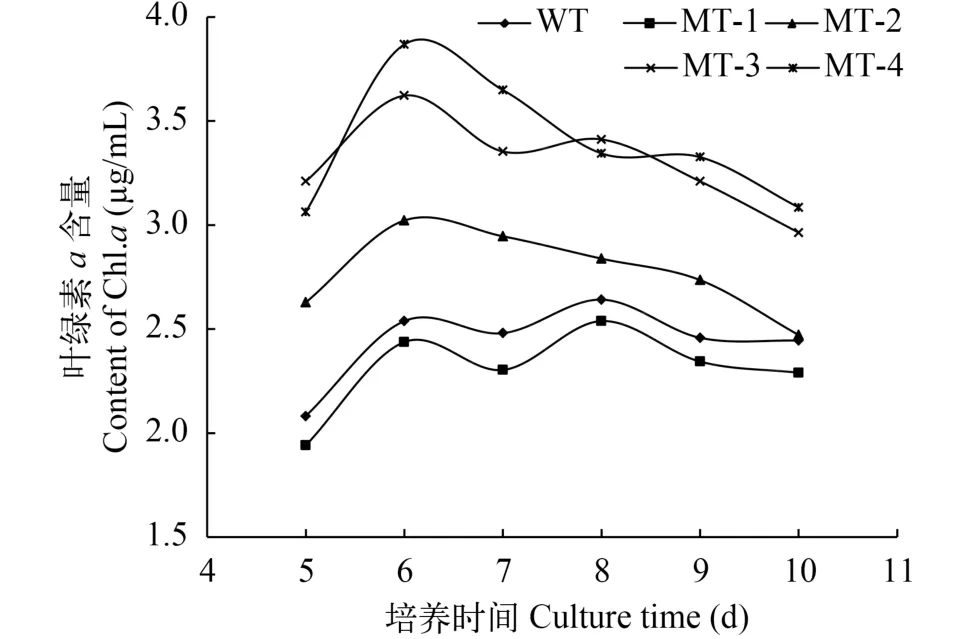

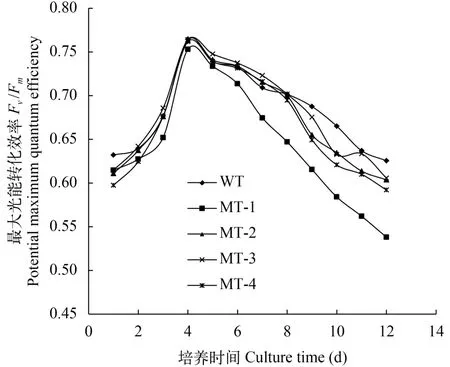

2.3 叶绿素a含量及Fv/Fm

如图 4所示, 除MT-1外, 其他3株诱变藻株的叶绿素a含量(μg/mL)显著高于野生型藻株。由图 5可以看出, 诱变藻株与野生型藻株的Fv/Fm在培养过程中变化趋势基本一致: 在第4天达到最大值, 随后逐渐降低, 在指数生长末期不同藻株之间Fv/Fm差异显著。

2.4 总脂含量和油脂产率

5株藻经柱状光生物反应器通气培养后, 总脂含量均达到了60%以上, 诱变藻株的总脂含量和油脂产率均显著高于野生型藻株(表 1), 其中, 藻株MT-4的油脂产率较野生型藻株提高了45%。

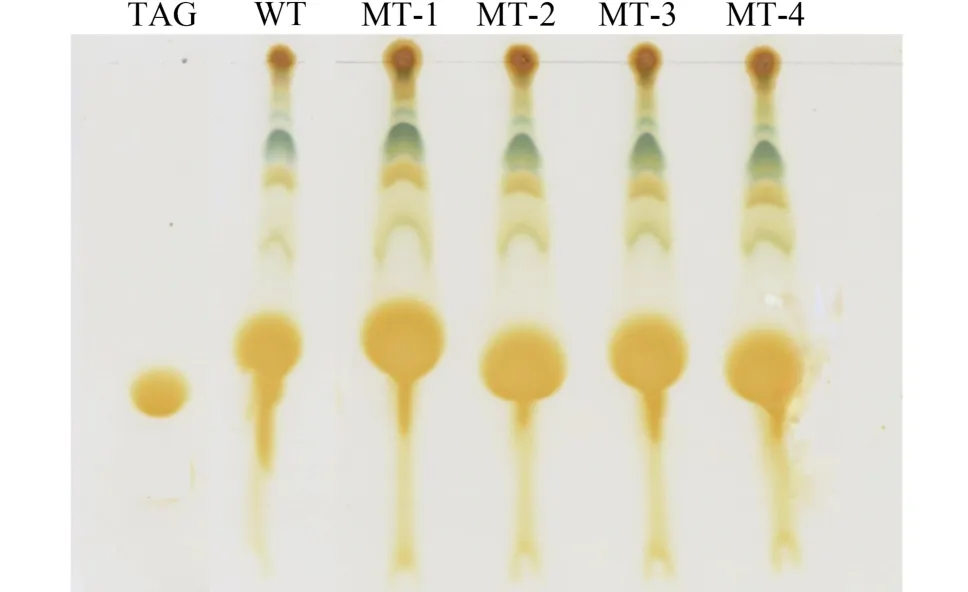

2.5 甘油三酯(TAG)分析

图 6中TAG标准品经层析染色后结果标示了TAG层析后的位置。通过对比硅胶板中部显现的圆形斑点的大小可以比较不同藻株总脂中TAG的相对含量。由结果可知, 4株诱变藻株的TAG含量均高于野生型藻株, 说明诱变藻株在TAG含量方面相对于野生型藻株更适合生物柴油的生产。

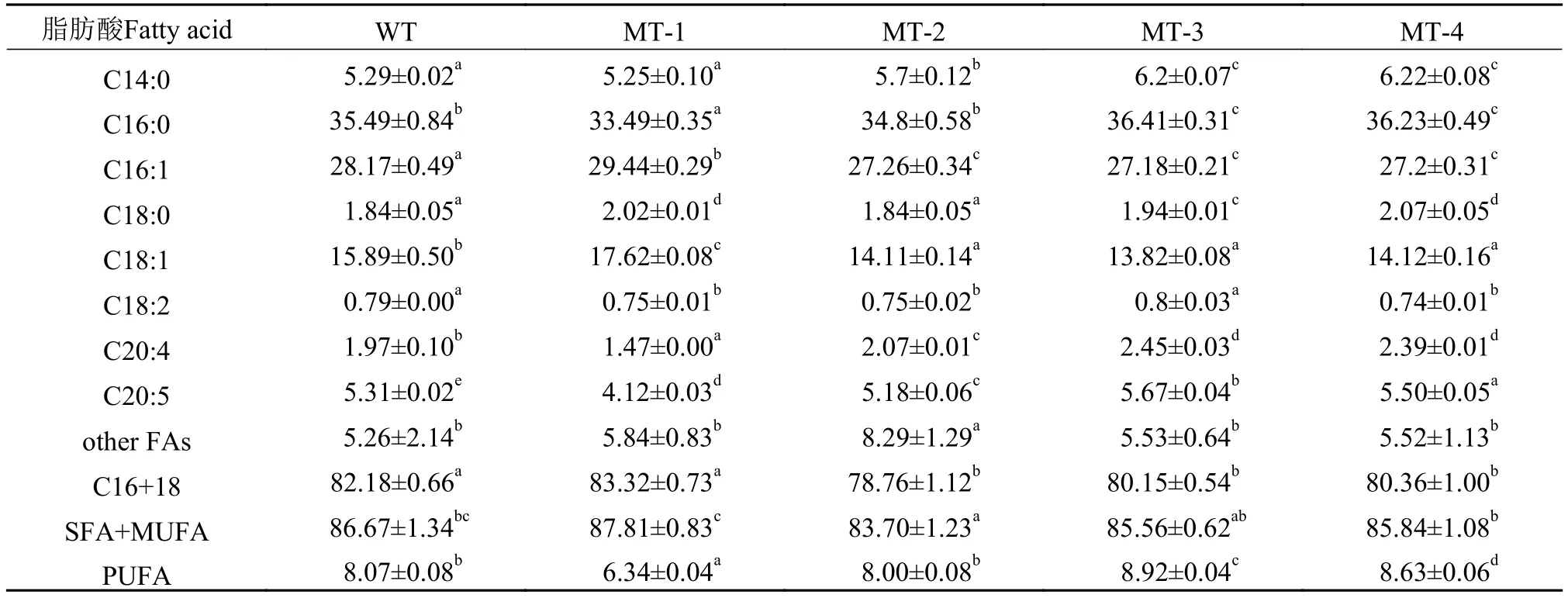

2.6 脂肪酸组成分析

由表 2可以看出, 微拟球藻脂肪酸主要由C14、C16、C18和C20组成, C16和C18之和占总脂肪酸含量的78%以上; 饱和脂肪酸(SFA)和单不饱和脂肪酸(MUFA)含量占总脂肪酸的比例达83%以上;而多不饱和脂肪酸(PUFA)含量只有6%—8%, 主要为C20:5(EPA), 含量为总脂肪酸的4%—5%。

3 讨论

流式细胞仪结合荧光染料(如BODIPY, 尼罗红)对藻种进行高通量筛选, 是获得高油脂含量优良能源微藻藻株的有力工具[19—21]。与尼罗红相比, BODIPY505/515在抗光漂白、荧光维持时间及适用范围上更有优势[22], 因此在富油微藻筛选中被广泛应用。由于不同种类的微藻细胞壁厚度存在差异, BODIPY505/515的使用条件(包括染料的浓度, 染色时间等)也有很大差别[20,23,24], 需要在实践中进行一定的探索。本实验通过设定不同的染色条件, 最终确定了海洋微拟球藻富油藻株的最佳筛选条件, BODIPY505/515的浓度为0.87 μg/mL, 染色时间10min,并通过流式细胞仪筛选获得了4株产油性能显著提升的优良藻株, 本文提供的方法可为其他富油微藻藻株的筛选提供一定参考。

图 3 微拟球藻野生株及诱变藻株生长曲线Fig. 3 Growth curves of wild and mutated N. oceanica

表 1 微拟球藻的比生长率、总脂含量、生物量和油脂产率Tab. 1 The specific growth rate, total lipid content, biomass and lipid productivity of N. oceanica

图 4 叶绿素a含量变化Fig. 4 Change of Chl a content during the culture time

图 5 培养过程中Fv/Fm的变化

总脂含量是微藻作为产油藻株的重要参考指标, 通过诱变选育的方式有望得到产油能力较原始藻株更为出色的藻种。本实验筛选得到的4株诱变株的总脂含量均显著高于野生型藻株(表 1), 且5株藻株的总脂含量均超过了干重的60%, 极具应用潜力。另外, 此结果与在锥形瓶中培养(总脂含量18%—25%)和报道[15]的吊袋光生物反应器培养时的总脂含量(22%—33%)有较大差异。可能原因如下: (1)培养条件的不同。培养条件对微藻油脂的积累有很大影响, 如: 温度[25]、光照[26,27]等。且本实验在柱状反应器培养时, 向其中通入了CO2, 为藻细胞的生长提供了充足的碳源, 而锥形瓶中培养时并没有CO2的通入; (2)朱葆华等[15]采用的是连续式的培养模式, 藻细胞始终稳定在指数生长期, 而本实验采用的是批次培养, 藻细胞能在较短时间内生长至平台期; 藻细胞胞内油脂主要在平台期进行积累, 因而本实验中油脂积累丰富。

图 6 微拟球藻野生株及4株诱变藻株的薄层层析图谱

表 2 微拟球藻野生株及4株诱变藻株的脂肪酸组成(占总脂肪酸的百分比)Tab. 2 Fatty acid composition of wild strain and four mutant strains of N. oceanica (% of total fatty acids)

4株微拟球藻诱变株在生长速率及生物量方面与野生型藻株相较呈显著提高, 进而油脂产率也显著高于野生型藻株(表 1)。对于生产生物柴油而言,仅油脂产率高是不够的, 还要有较高的中性脂含量(主要为TAG)及合适的脂肪酸组成。因为TAG是生产生物柴油的主要原料, 而微藻的脂肪酸组成是决定生物柴油冷凝点、氧化稳定性、黏度、润滑度、点火温度等的重要因素[28]。本实验结果显示, 4株诱变藻株的TAG含量相比于野生型藻株更具优势(图 6)。对于脂肪酸组成而言, 一般认为由C16和C18组成的SFA及MUFA是最适合用来生产生物柴油的脂肪酸, 在本研究中, 5株海洋微拟球藻的SFA和MUFA之和占到了总脂肪酸含量的83%以上, 且主要以C16和C18为主, 而PUFA的含量只有6%—8%, 该脂肪酸组成能使生物柴油具有较高的十六烷值及较强的抗氧化性, 因此非常适合用来生产生物柴油。

综上所述, 结合油脂产率、中性脂含量和脂肪酸组成的分析, 4株诱变株经柱状光生物反应器评价后表现出优良的产油性状, 证实了本实验筛选方法的有效性。藻株MT-1、MT-2、MT-3、MT-4产油潜力良好, 有望用于规模化生产。

致谢:

感谢宁波大学海洋学院张琳在微拟球藻富油藻株筛选工作中的贡献。

[1]Singh B, Guldhe A, Rawat I, et al. Towards a sustainable approach for development of biodiesel from plant and microalgae [J]. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2014, 29(7): 216—245

[2]Chernova N I, Kiseleva S V, Popel O S. Efficiency of the biodiesel production from microalgae [J]. Thermal Engineering, 2014, 61(6): 399—405

[3]Kumar K, Ghosh S, Angelidaki I, et al. Recent developments on biofuels production from microalgae and macroalgae [J]. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016, 65: 235—249

[4]Milano J, Ong H C, Masjuki H H, et al. Microalgae biofuels as an alternative to fossil fuel for power generation [J]. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016, 58: 180—197

[5]Jones C S, Mayfield S P. Algae biofuels: versatility for the future of bioenergy [J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2012, 23(3): 346—351

[6]Gouveia L, Oliveira A C. Microalgae as a raw material for biofuels production [J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 2009, 36(2): 269—274

[7]Baicha Z, Salar-García M J, Ortiz-Martínez V M, et al. A critical review on microalgae as an alternative source for bioenergy production: A promising low cost substrate for microbial fuel cells [J]. Fuel Processing Technology, 2016, 154(15): 104—116

[8]Ma Y, Wang Z, Yu C, et al. Evaluation of the potential of 9 Nannochloropsis strains for biodiesel production [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2014, 167(3): 503—509

[9]Anandarajah K, Mahendraperumal G, Sommerfeld M, et al. Characterization of microalga Nannochloropsis sp. mutants for improved production of biofuels [J]. Applied Energy, 2012, 96(8—9): 371—377

[10]Cooper M S, Hardin W R, Petersen T W, et al. Visualizing “green oil” in live algal cells [J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2010, 109(2): 198—201

[11]Duan X, Li P, Li P, et al. The synthesis of polarity-sensitive fluorescent dyes based on the BODIPY chromophore [J]. Dyes and Pigments, 2011, 89(3): 217—222

[12]Zhu B, Sun F, Yang M, et al. Large-scale biodiesel production using flue gas from coal-fired power plants with Nannochloropsis microalgal biomass in open raceway ponds [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2014, 174: 53—59

[13]Henriques M, Silva A, Rocha J. Extraction and quantification of pigments from a marine microalga: a simple and reproducible method [A]. In: A. Méndez-Vilas (Eds.), Communicating Current Research and Educational Topics and Trends in Applied Microbiology [C]. Badajoz: Formatex Research Center. 2007, 586—593

[14]Bligh E G, Dyer W J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification [J]. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology, 1959, 37(8): 911—917

[15]Zhu B H, Shi H P, Sun F Q, et al. Evaluation of six N. oceanica strains with high oil productivity in pilot scale [J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2016, 46(7): 15—20 [朱葆华, 石红萍, 孙发强, 等. 6株高产油微拟球藻的中试培养评价研究. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2016, 46(7): 15—20]

[16]Song M, Pei H, Hu W, et al. Evaluation of the potential of 10 microalgal strains for biodiesel production [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2013, 141(4): 245—251

[17]Yu E T, Zendejas F J, Lane P D, et al. Triacylglycerol accumulation and profiling in the model diatoms Thalassiosira pseudonana and Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Baccilariophyceae) during starvation [J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2009, 21(6): 669—681

[18]Lepage G, Roy C C. Improved recovery of fatty acid through direct transesterification without prior extraction or purification [J]. Journal of Lipid Research, 1984, 25(12): 1391—1396

[19]Montero M F, Aristizábal M, García Reina G. Isolation of high-lipid content strains of the marine microalga Tetraselmis suecica for biodiesel production by flow cytometry and single-cell sorting [J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2011, 23(6): 1053—1057

[20]Thi-Thai, Doan Y, Philip O J. Enhanced lipid production in Nannochloropsis sp. using fluorescence-activated cell sorting [J]. Global Change Biology Bioenergy, 2011, 3(3): 264—270

[21]Velmurugan N, Sung M, Yim S S, et al. Evaluation of intracellular lipid bodies in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strains by flow cytometry [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2013, 138: 30—37

[22]Govender T, Ramanna L, Rawat I, et al. BODIPY staining, an alternative to the Nile Red fluorescence method for the evaluation of intracellular lipids in microalgae [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2012, 114(2): 507—511

[23]Liu Y N, Yao C H, Zhou J N, et al. Rapid method for lipid content quantification of microalgae based on BODIPY fluorescence [J]. Chinese Journal of Bioprocess Engineering, 2013, 11(06): 68—72 [刘亚男, 姚长洪, 周建男, 等. 使用BODIPY荧光染料快速测定微藻油脂含量方法. 生物加工过程, 2013, 11(06): 68—72]

[24]Brennan L, Blanco Fernández A, Mostaert A S, et al. Enhancement of BODIPY505/515 lipid fluorescence method for applications in biofuel-directed microalgae production [J]. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2012, 90(2): 137—143

[25]Li X, Hu H Y, Zhang Y P. Growth and lipid accumulation properties of a freshwater microalga Scenedesmus sp. under different cultivation temperature [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2011, 102(3): 3098—3102

[26]He Q, Yang H, Wu L, et al. Effect of light intensity on physiological changes, carbon allocation and neutral lipid accumulation in oleaginous microalgae [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2015, 191: 219—228

[27]Ra C H, Kang C H, Jung J H, et al. Effects of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on the accumulation of lipid content using a two-phase culture process with three microalgae [J]. Bioresource Technology, 2016, 212: 254—261

[28]Hoekman S K, Broch A, Robbins C, et al. Review of biodiesel composition, properties, and specifications [J]. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2012, 16(1): 143—169

SCREENING OF LIPID-RICH NANNOCHLOROPSIS OCEANICA MUTANTS AND EVALUATION USING A BUBBLE COLUMN PHOTOBIOREACTOR

HE Wen-Dong1, ZHU Bao-Hua1, FENG Lei-Li1, CHANG Ya-Qing1, YANG Guan-Pin2and PAN Ke-Hou1,3

(1. Key Laboratory of Mariculture (Ocean University of China), Ministry of Education, Qingdao 266003, China; 2. College of Marine Life Science, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China; 3. Laboratory for Marine Fisheries and Aquaculture, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266003, China)

After industrialization occurred, fossil fuel reserves decreased drastically, and environmental pollution caused by fossil fuel consumption became more serious. Thus, clean and renewable energy alternatives have recently attracted increasing amounts of attention. Microalgae have many advantages, such as a high growth rate, suitable fatty acid profiles and high lipid content, which makes them one of the most promising sources for renewable energy production. However, making a profit from biodiesel production based on microalgae is difficult because of the high cost. There are various strategies to reduce the cost of biodiesel production, such as breeding the best microalgae strains through chemical mutagenesis, which is one of the most important methods. Although this method is effective, extraordinarily heavy follow-up work impedes its promotion and application. Fortunately, flow cytometry and lipophilic fluorescent dyes (BODIPY505/515) provide the opportunity to screen for the best mutants using high throughput.

In this study, multiple mutants of Nannochloropsis oceanica were obtained by using chemical mutation (nitrosoguanidine, NTG). We developed a method based on flow cytometry and BODIPY505/515, which can screen microalgal candidates using high throughput. Our results showed that the optimal concentration and staining time for BODIPY505/515were 0.87 μg/mL and 10min, respectively. Based on this method, four outstanding microalgal strains were obtained. To verify the reliability of the screening method, we further investigated the performance of these four strains cultivated in a column photobioreactor. The results showed that lipid productivity of the four mutants was remarkably higher than that of the wild type, and the highest value was 27.32 mg/(L·d), demonstrating that this method is effective and feasible. To further evaluate the potential of candidates for biodiesel production, we investigated factors such as the fatty acid profiles, chlorophyll a, and PSII quantum efficiency. The results indicated that all of these four mutants possessed great potential for biodiesel production.

Biodiesel; Nannochloropsis oceanica; BODIPY505/515; Mutants screening; Photobioreactor

10.7541/2017.139

2016-11-01;

2017-02-16

国家重点基础研究发展计划项目(2011CB200901和2011CB200904); 国家自然科学基金项目(31372518); 宁波大学“水产”浙江省重中之重学科开放基金(xkzsc1517)资助 [Supported by Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (2011CB200901, 2011CB200904); National Natural Science Foundation of China (31372518); Ningbo University “Fisheries”Priority Subject Open Fund of Zhejiang Province]

何文栋(1993—), 男, 河南南阳人; 硕士研究生; 主要从事微藻诱变育种研究。E-mail: wd_he2010@163.com

潘克厚, 博士; 主要从事海洋生态学研究。E-mail: qdkhpan@126.com

S968.4

A

1000-3207(2017)05-1112-06