淀粉样前体蛋白在神经发生中的作用与阿尔茨海默病关系的研究进展

2017-07-10朱红梅张凤兰肖志成陈芳昆明医科大学分子临床医学研究院云南省干细胞和再生医学重点实验室云南昆明650500莫纳什大学免疫与干细胞实验室澳大利亚墨尔本3800昆明医科大学基础医学院云南昆明650500

朱红梅 张凤兰 肖志成,2* 陈芳.昆明医科大学分子临床医学研究院,云南省干细胞和再生医学重点实验室, 云南 昆明 650500;2.莫纳什大学免疫与干细胞实验室,澳大利亚 墨尔本 3800;3.昆明医科大学基础医学院,云南 昆明 650500

淀粉样前体蛋白在神经发生中的作用与阿尔茨海默病关系的研究进展

朱红梅1张凤兰1肖志成1,2*陈芳3*

1.昆明医科大学分子临床医学研究院,云南省干细胞和再生医学重点实验室, 云南 昆明 650500;2.莫纳什大学免疫与干细胞实验室,澳大利亚 墨尔本 3800;3.昆明医科大学基础医学院,云南 昆明 650500

阿尔茨海默病,俗称老年痴呆,由德国外科医生Alzheimer首次发现,是一种进行性发展、致死性神经系统退行性疾病。该病是目前最常见的一种失智症(俗称痴呆症,Dementia),但这种失智不同于正常老化。迄今为止AD具体的发病机制仍未明确、也没有精准的早期筛查和诊断手段及有效控制病情的治疗方法。近年来大量研究证实成年哺乳动物的中枢神经系统终身存在着神经发生。这为脑损伤和神经系统变性疾病的治疗带来了希望。文章将对成年中枢神经系统神经发生的过程及参与AD病程的关键分子APP在神经发生方面的最新发现进行综述,以期为本领域或相关研究提供借鉴或参考。

淀粉样前体蛋白; 神经发生;阿尔茨海默病

阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer disease,AD) 是发生于老年及老年前期最常见的,以进行性痴呆为特征的中枢神经系统退行性疾病。该病以近期记忆障碍、认知功能障碍、语言障碍及人格异常等神经精神症状为显著临床表现[1],发病隐匿,呈不可逆的进行性进展表现,病程可长达20~30年,最后呈严重痴呆以至植物人状态。随着人类寿命的延长及人口老龄化,AD对人类健康的危害日益突出,是仅次于心血管病、癌症、脑卒中之后严重威胁老年人生命健康的高发病,已成为当前老年医学面临的最为严峻的医学问题之一[2-3]。然而,自1906发现该病至今,其发病机制仍未完全明确,也无精准的早期诊断手段及有效的治疗方法。神经干细胞(neural stem cells, NSCs)在一定的条件下可增殖分化为神经元和神经胶质细胞,进而整合到现有的神经回路中,参与神经功能的维持及修复等过程,此称之为神经发生。传统观念认为,神经发生主要存在于胚胎发育期,成年哺乳动物中无神经发生。近年来大量研究证实成年哺乳动物的中枢神经系统终身存在着神经发生,这为脑损伤及AD等发病机制的研究开辟了新思路。对成体大脑神经发生的研究将对临床脑损伤的修复及AD等疾病的治疗具有重要意义[4-6]。此外,近年来研究发现AD发生发展相关的关键分子和信号通路同时影响了神经发生,并有研究证实海马神经发生的改变要早于AD的特征性损伤[7-10]。由于在AD的病程中,海马是最易受损的区域之一,该部位的AD病理变化表现得较为明显,且该脑区的受损往往导致了AD的最早期症状、学习记忆缺陷的出现。因此,研究神经发生,尤其是海马神经发生的变化及机制,已成为当前AD病理机制研究的一个新的浪潮。由于AD患者普遍存在β淀粉样蛋白(beta-Amyloid protein,Aβ)的高表达,而APP是导致Aβ生成的关键分子。APP及其水解产物在AD的病理过程中扮演着重要的作用且能影响神经发生。本文主要介绍中枢神经系统神经发生的过程及参与AD病程的关键分子APP在成体神经发生中的作用,从而进一步明确APP在成体神经发生中的作用与AD发病的联系,以期为AD发病机制的研究提供思路和参考。

1 APP与AD的关系

近年来诸多研究表明,AD是一种多病因参与的复杂疾病。该病主要包括两种类型,家族性阿尔茨海默病(FAD)和散发性阿尔茨海默病(SAD),临床上较为常见的是SAD。目前有研究认为,FAD主要由PS1、PS2和APP基因突变所致[11-13];而SAD的发病机制较为复杂,是多因素共同作用的结果。但这两种类型疾病的进展和病理变化基本相同,其主要的病理改变包括β淀粉样蛋白沉积引起的老年斑(senile plaque, SP),细胞骨架蛋白Tau蛋白过度磷酸化引起的神经元内神经元纤维缠结(neurofibrillary tangle, NFT)及大面积的神经元死亡[14-15]。大量研究证明β淀粉样蛋白(beta-Amyloid protein,Aβ)在AD发病中,起重要病理作用,是SP的核心成分[14-15]。其在体内存在着多种形态:包括可溶性的游离态、寡聚态及中间态的初原纤维(protofibrils)及不溶性的原纤维(fibrils)。后者易沉积形成SP。但寡聚态的Aβ被认为具有更强的毒性,是AD的主要病因,此为AD发病的“Aβ假说”,该假说是目前已被广泛接受的AD的主要致病机理。而淀粉样前体蛋白(amyloid precursor protein,APP)是Aβ的前体蛋白,这说明Aβ聚集所产生的神经毒性,需要APP的酶解加工过程的参与。此外,APP基因敲除小鼠在小鼠发育、突触功能、学习记忆等方面表现异常[16-20]。可见,APP蛋白在生理过程中扮演了诸多重要的角色,其基因结构及功能的异常可能与AD的发病密切相关。

2 APP的主要结构及裂解过程

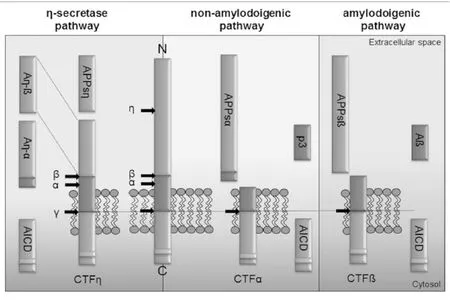

APP是一种广泛存在于全身组织细胞上的单次跨膜蛋白,由多个功能区组成,包括大的N-末端胞外结构域、跨膜区(即Aβ区)及小的C-末端胞浆区。其中胞外区是一个较复杂的结构,由几个独立的结构域组成,具有相对独立的功能。据最新文献报道,APP可被α、β、γ和η分泌酶切割形成不同的肽段[21-26]。并在这些分泌酶的作用下以3种不同的途径裂解(见图1):①非淀粉样途径:为APP的主要裂解途径,裂解位点在Aβ序列间,裂解酶为α分泌酶(和γ分泌酶)。APP先经α分泌酶在α位剪切,在APP的N端产生可溶性的APP片段(sAPPα),在C端产生CTFα片段,CTFα再经γ分泌酶剪切产生P3及胞浆内片段AICD,此途径不形成Aβ。②淀粉样途径:为APP的次要裂解途径,裂解位点在Aβ序列两侧,裂解酶为β和γ分泌酶。此途径APP先经β分泌酶剪切,可在N端产生sAPPβ片段,在C端产生CTFβ片段,CTFβ再经γ分泌酶剪切就会产生全长的Aβ[21,27]。其中含有42个氨基酸的Aβ42具有较强的神经毒性,且最易聚集和沉积,最终形成老年斑,可导致神经元退行性变和痴呆[28-29]。③η分泌酶途径:存在多个裂解位点,但此途径不生成Aβ。其中,前两个途径为APP的经典裂解途径,在病理状态下,APP的次要裂解途径(Aβ途径)发挥着主要作用。

对APP裂解的调节,是生理和病理过程的一个关键事件。然而,APP的各种裂解产物的病理生理意义尚未研究清楚,可能与APP的定位、翻译后修饰及寡聚化状态相关[29-34]。

3 成体神经发生

据大量文献报道,NSCs不仅存在于发育中的哺乳动物神经系统,而且还存在于成年动物脑内[35-38]。成体脑中的NSCs通过分裂、增殖后产生神经前体细胞(neural precursor cells,NPCs),它们经过迁移、分化形成成熟的神经元,进而整合入神经网络发挥作用,这一系列过程称为(成体)神经发生(neurogenesis)。在成年哺乳类动物大脑中主要有2个区域存在持续的神经发生:脑室室管膜下区(subventricular zone,SVZ)和海马齿状回颗粒下区(subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus,SGZ),以维持嗅球及海马神经元的更新。神经发生的程度与这两个成体神经发生的关键脑区神经前体细胞的迁移和分化及新生神经元的存活密切相关。

图1 APP裂解途径(引自参考文献[24])

4 APP在神经发生中的作用

大量研究表明APP的裂解产物对神经干细胞的增殖和分化具有重要的调控作用。笔者对研究报道较多的sAPPα、AICD及Aβ共3个主要的裂解产物在神经发生中的作用进行阐述。

4.1 sAPPα正向调控神经发生 早期有文献指出,从胎鼠脑组织中分离SVZ源性的NPCs,sAPPα可促进其增殖[39]。有研究认为,sAPPα促NPC增殖可能与其结构与生长因子类似有关[40]。2004年,Caille等[41]首次报道sAPPα对成体神经发生有作用:将sAPPα注射入小鼠侧脑室,可观察到NPC的数量增多;相反地,用α分泌酶抑制剂阻断sAPPα的生成或用APP的反义寡核苷酸下调APP的生成,均导致NPC的数量减少。这说明,sAPPα能促进NPCs增殖。他们还探讨了其促增殖的作用可能与SVZ区的A细胞的增殖有关。可见,sAPPα可促进胚胎和成体的SVZ源性的NPC增殖。最新的报道指出,sAPPα在体外实验中,可促进另一成体发生系统—SGZ区的NPC的增殖,并促进细胞存活[42]。向衰老C57BL/6小鼠(20个月)的脑室单次注射sAPPα可逆转由衰老引起的神经发生能力的减退(很大原因是NPC数量的减少)[43]。可见,sAPPα对成体神经发生是有利的,其正向调控神经发生。

4.2 AICD负向调控神经发生 2008年Ma Q H等[44]首次报道了AICD在神经发生方面的作用,并发现TAG1是APP的功能性配体,TAG1和APP相互作用导致了APP胞内结构域AICD的释放,再在胞内支架蛋白Fe65的作用下转运至细胞核,负性调控胚胎SVZ源性的神经发生。次年,有文献报道,在人类AD患者脑内发现AICD高水平表达[45]。这进一步说明AICD与AD的发病机制密切相关。到2010年,Ghosal k等[46]在内源性APP不存在的情况下,排除Aβ及其他APP裂解产物的作用,单看AICD的作用,发现:AICD损害成体海马神经发生,且这种破坏作用表现为年龄依赖的方式。在AICD转基因小鼠上,6周时海马区成体神经发生未见异常,但从3个月持续到12个月时,均表现出成体神经发生受损,且这种受损是由于炎症反应导致细胞的增殖和存活能力下降引起的。肖志成研究团队探讨了AICD抑制神经发生的可能机制。其研究结果表明,AICD作为miR-663的转录因子,通过miR-663抑制FBXL18和CDK6基因的表达,从而抑制人源的NSCs向神经元分化,最终负性调控神经发生[47]。可见,AICD无论对胚胎还是成体神经发生都是不利的,其通过不同的机制负向调控神经发生。

4.3 Aβ双向调控神经发生 Haughey等的体外实验较早的报道了Aβ的大量沉积影响了人大脑皮层的神经前体细胞的功能,抑制其增殖和向神经元分化,并最终导致细胞凋亡[48]。随后已经有大量的研究用AD模型鼠的体内实验证实Aβ对神经发生的的作用,研究结果表明SGZ源性的神经前体细胞向神经元分化的能力及新生神经元的存活能力均减退,近而导致神经发生能力受损[49-50]。高浓度Aβ42注射入小鼠侧脑室,可抑制SVZ区及SGZ区源性的NSCs的增殖及向神经元分化[51-52]。然而,也有文献报道,在体外实验中,低浓度寡聚肽的Aβ42能促进胚胎及成体的NSCs向神经元分化[53-54]。纤维态的Aβ(即不溶性Aβ)可减少人胚胎干细胞向神经元分化,但增加GFAP+神经前体细胞的数量[55]。可见,Aβ对神经发生的影响是比较复杂的,受其浓度和形态结构的影响。低浓度寡聚肽的Aβ对神经发生起正向调节的作用,高浓度及不溶性Aβ对神经发生起负向调节的作用。

因此,这些研究结果显示,APP在神经发生过程中具有重要作用,其主要通过影响NSCs的增殖、NSCs/NPCs向神经元的分化和新生细胞的存活调控成体神经发生。sAPPα已显示出对AD治疗的潜在价值。在最近的已修订的阿尔兹海默病的诊断指南中,已明确将sAPPα及相应的分泌酶作为AD早期诊断的生物标记物[56],修复sAPPα有望为AD的治疗带来可能[57]。

5 神经发生的改变与AD的关系

目前越来越多的研究认为,成体神经发生在正常的记忆功能维持中扮演着重要的作用[58-59]。当成体神经发生受损时,则会使某些特定类型的记忆受损,如空间学习记忆能力[60-62],导致空间辨别和记忆能力出现障碍,这恰恰是AD典型的临床表现之一,提示成体神经发生受损对AD是及其不利的一个因素。与此同时,大量的研究报道了在AD患者和AD模型鼠上发现成体神经发生受损[63-69]。在衰老和AD患者脑内观察到神经前体细胞减少最为明显[70];在早发性AD患者的血浆及脑脊液中检测到干细胞因子(stem cell factor, SCF,是一种造血生长因子,在脑内有支持神经发生的作用)的水平降低[71];在早发性AD模型鼠(APPswe/PS1dE9)的SVZ区及SGZ区NPC的增殖以及向神经元分化的能力减退[65,72],并在9个月时,这种神经发生的能力减退最为明显[73]。然而,Demars等[74]研究发现,在早发性AD模型鼠的早期,2个月时就发现SVZ区及SGZ区NPC的增殖以及分化能力严重受损。此外,在AICD转基因小鼠上发现,神经发生受损第一次被检测到是在3个月时,比记忆受损(4~5个月时才出现)出现早[75]。在3xTg AD模型鼠上也发现相似的现象:成体神经发生受损较AD的其他病理特征先检测出来[76]。因此,这些研究结果表明,成体神经发生能力受损可能导致了AD患者出现海马依赖的及嗅球依赖的记忆缺失及认知功能受损。

6 小结

综上所述,AD是一种多病因参与的复杂疾病,神经发生是其中的一个重要因素和关键环节。在AD病理进程中起关键作用的分子APP参与了这一重要事件。但由于APP类型的多样性,以及其水解产物在神经发生方面表现的多样性,使得将其作为诊断标记物及靶向治疗的可行性和有效性变得复杂和困难。尽管目前已将sAPPα作为AD 早期诊断的指标及治疗方向,但其影响神经发生的作用机制仍未明确。因此,仍需大量的研究来探讨APP及其水解产物对神经发生影响的作用机制。后续研究仍任重道远。

[1]Goedert M, Spillantini M G. A Century of Alzheimer’s Disease[J]. Science, 2006, 314(5800):777-781.

[2] Schaller S, Mauskopf J, Kriza C, et al. The main cost drivers in dementia: a systematic review[J]. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 2015, 30(2):111-129.

[3] Lazarov O, Marr R A. Neurogenesis and Alzheimer’s disease: at the crossroads[J]. Experimental Neurology, 2010, 223(2):267-281.

[4]Lledo P M, Alonso M, Grubb M S. Adult neurogenesis and functional plasticity in neuronal circuits.[J].Nature Reiview Neuroscience, 2006, 7(3):179-193.

[5]Bergmann, O., Spalding, K. L., Frisén, J.Adult neurogenesis in humans[J].Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.,2015,7:a018994.

[6]Kempermann, G., Song, H.,Gage, F. H.Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus[J].Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med.,2015, 5:a018812.

[7] Demars M, Hu Y S, Gadadhar A, et al. Impaired neurogenesis is an early event in the etiology of familial Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic mice[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 2010, 88(10):2103-2117.

[8] Ghosal K, Stathopoulos A, Pimplikar S W. APP Intracellular Domain Impairs Adult Neurogenesis in Transgenic Mice by Inducing Neuroinflammation[J]. Plos One, 2010, 5(7):e11866.

[9] Wang J M, Singh C, Liu L, et al. Allopregnanolone reverses neurogenic and cognitive deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 107(14):6498-6503.

[10] Sherrington R, Rogaev E I, Liang Y, et al. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial, Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Nature, 1995, 375(6534):754-760.

[11] Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkaj P, et al. Candidate Gene for the Chromosome 1 Familial Alzheimer’s Disease Locus[J]. Science, 1995, 269(5226):973-977.

[12]Scheltens P,Blennow K,Breteler M M,et al.Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Lancet, 2016, 388(10043):505-517.

[13]Selkoe D J. Alzheimer’s Disease: Genes, Proteins, and Therapy[J]. Physiological Reviews, 2001, 81(2):741-766.

[14] Selkoe D J, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25years[J]. Embo Molecular Medicine, 2016, 8(6):595-608.

[15] Magara F, Wolfer D P. Genetic background changes the pattern of forebrain commissure defects in transgenic mice underexpressing the β-amyloid-precursor protein[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1999, 96(8):4656-4661.

[16] Wild K, August A, Pietrzik C U, et al. Structure and Synaptic Function of Metal Binding to the Amyloid Precursor Protein and its Proteolytic Fragments[J]. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 2017(10):21.

[17]Weyer S W, Klevanski M, Delekate A, et al. APP and APLP2 are essential at PNS and CNS synapses for transmission, spatial learning and LTP[J]. Embo Journal, 2011, 30(11):2266-2280.

[18]Midthune B, Tyan S H, Walsh J J, et al. Deletion of the amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2) does not affect hippocampal neuron morphology or function[J]. Molecular & Cellular Neuroscience, 2012, 49(4):448-455.

[19]Weyer S W, Zagrebelsky M, Herrmann U, et al. Comparative analysis of single and combined APP/APLP knockouts reveals reduced spine density in APP-KO mice that is prevented by APPsα expression[J]. ActaNeuropathologica Communications, 2014, 2(1):36.

[20]Zou C, Crux S, Marinesco S, et al. Amyloid precursor protein maintains constitutive and adaptive plasticity of dendritic spines in adult brain by regulating D‐serine homeostasis[J]. Embo Journal, 2016, 35(20):2213-2222.

[21] Nicolas M, Hassan B A. Amyloid precursor protein and neural development[J]. Development, 2014, 141(13):2543.

[22]Kitaguchi N, Takahashi Y, Tokushima Y, et al. Novel precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid protein shows protease inhibitory activity[J]. Nature, 1988, 331(6156):530-532.

[23] König G, Mönning U, Czech C, et al. Identification and differential expression of a novel alternative splice isoform of the beta A4 amyloid precursor protein (APP) mRNA in leukocytes and brain microglial cells.[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1992, 267(15):10804-10809.

[24] Haass C, Hung A Y, Selkoe D J. Processing of beta-amyloid precursor protein in microglia and astrocytes favors an internal localization over constitutive secretion[J]Journal of Neuroscience, 1991, 11(11):3783-3793.

[25] Baumkötter F, Wagner K, Eggert S, et al. Structural aspects and physiological consequences of APP/APLP trans-dimerization[J]. Experimental Brain Research, 2012, 217(3):389-395.

[26]Ludewig S, Korte M. Novel Insights into the Physiological Function of the APP (Gene) Family and Its Proteolytic Fragments in Synaptic Plasticity[J]. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 2017(9):161.

[27]Roychaudhuri R, Yang M, Hoshi M M, et al. Amyloid beta-protein assembly and Alzheimer disease[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2009, 284(8):4749-4753.

[28] Selkoe D J. Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 2011, 3(7).

[29]Haass C, Kaether C, Thinakaran G, et al. Trafficking and Proteolytic Processing of APP[J]. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2012, 2(5):a006270.

[30]Kienlencampard P, Tasiaux B, Hees J V, et al. Amyloidogenic Processing but not AICD Production Requires a Precisely Oriented APP Dimer Assembled by Transmembrane GXXXG Motifs[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2008, 283(12):7733-7744.

[31]Eggert S, Midthune B, Cottrell B, et al. Induced dimerization of the amyloid precursor protein leads to decreased amyloid-beta protein production[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2009, 284(42):28943-28952.

[32]Muresan V, Muresan Z L. Amyloid-β precursor protein: Multiple fragments, numerous transport routes and mechanisms[J]. Experimental Cell Research, 2015, 334(1):45-53.

[33]Winkler E, Julius A, Steiner H, et al. Homodimerization Protects the Amyloid Precursor Protein C99 Fragment from Cleavage by γ-Secretase[J]. Biochemistry, 2015, 54(40):6149-6152.

[34]Chasseigneaux S, Allinquant B. Functions of Aβ, sAPPα and sAPPβ : similarities and differences[J]. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2012, 120(Supplement s1):99-108.

[35]Kempermann G, Kuhn H G, Gage F H. More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment[J]. Nature, 1997, 386(6624):493-495.

[36]Cameron H A, Woolley C S, Mcewen B S, et al. Differentiation of newly born neurons and glia in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat[J]. Neuroscience, 1993, 56(2):337-344.

[37]Gould E, Vail N, Wagers M, et al. Adult-generated hippocampal and neocortical neurons in macaques have a transient existence[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2001, 98(19):10910.

[38]Eriksson P S, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus[J]. Nature Medicine, 1998, 4(11):1313-1317.

[39]Ohsawa I, Takamura C, Morimoto T, et al. Amino-terminal region of secreted form of amyloid precursor protein stimulates proliferation of neural stem cells[J]. European Journal of Neuroscience, 1999, 11(6):1907-1913.

[40]Rossjohn J, Cappai R, Feil S C, et al. Crystal structure of the N-terminal, growth factor-like domain of Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein[J]. Nature Structural Biology, 1999, 6(4):327-331.

[41]Caillé I, Allinquant B, Dupont E, et al. Soluble form of amyloid precursor protein regulates proliferation of progenitors in the adult subventricularzone[J]. Development, 2004, 131(9):2173-2181.

[42]Baratchi S, Evans J, Tate W P, et al. Secreted amyloid precursor proteins promote proliferation and glial differentiation of adult hippocampal neural progenitor cells[J]. Hippocampus, 2012, 22(7):1517-1527.

[43]Demars, Michael P, Hollands, et al. Soluble amyloid precursor protein-alpha rescues age-linked decline in;neural progenitor cell proliferation[J]. Neurobiology of Aging, 2013, 34(10):2431-2440.

[44]Ma Q H, Futagawa T, Yang W L, et al. A TAG1-APP signalling pathway through Fe65 negatively modulates neurogenesis[J]. Nature Cell Biology, 2008, 10(3):283-294.

[45]Ghosal K, Vogt D L, Liang M, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease-Like Pathological Features in Transgenic Mice Expressing the APP Intracellular Domain[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(43):18367-18372.

[46]Ghosal K, Stathopoulos A, Pimplikar S W. APP Intracellular Domain Impairs Adult Neurogenesis in Transgenic Mice by Inducing Neuroinflammation[J]. Plos One, 2010, 5(7):e11866.

[47]Shu R, Wong W, Ma Q H, et al. APP intracellular domain acts as a transcriptional regulator of miR-663 suppressing neuronal differentiation[J]. Cell Death & Disease, 2015, 6(2):e1651.

[48]Haughey N J, Dong L, Nath A, et al. Disruption of neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of adult mice, and in human cortical neuronal precursor cells in culture, by amyloid β-peptide[J]. NeuroMolecular Medicine, 2002, 1(2):125-135.

[49]Wen P H, Hof P R, Chen X, et al. The presenilin-1 familial Alzheimer disease mutant P117L impairs neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult mice[J]. Experimental Neurology, 2004, 188(2):224-237.

[50]Donovan M H, Yazdani U, Norris R D, et al. Decreased adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the PDAPP mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 2006, 495(1):70-83.

[51]Haughey N J, Nath A, Chan S L, et al. Disruption of neurogenesis by amyloid β‐peptide, and perturbed neural progenitor cell homeostasis, in models of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. 2003, 83(6):1509-1524.

[52]Haughey N J, Dong L, Nath A, et al. Disruption of neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of adult mice, and in human cortical neuronal precursor cells in culture, by amyloid β-peptide[J]. NeuroMolecular Medicine, 2002, 1(2):125-135.

[53]López-Toledano M A, Shelanski M L. Neurogenic effect of beta-amyloid peptide in the development of neural stem cells[J]. Journal of Neuroscience, 2004, 24(23):5439-5444.

[54]Choi H S, Heo C J, Jang K A. Effects of the monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ42 peptides on the proliferation and differentiation of adult neural stemcells from SVZ[J]. Neuroscience Research, 2007, 58(1):S56.

[55]Malmsten L, Vijayaraghavan S, Hovatta O, et al. Fibrillar β-amyloid 1-42 alters cytokine secretion, cholinergic signalling and neuronal differentiation[J]. Journal of Cellular & Molecular Medicine, 2014, 18(9):1874-1888.

[56]Perneczky R, Alexopoulos P, Kurz A. Soluble amyloid precursor proteins and secretases as Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers[J]. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 2014, 20(1):8-15.

[57]Habib A, Sawmiller D, Tan J. Restoring Soluble Amyloid Precursor Protein α Functions as a Potential Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 2017,95(4):973-991.

[58] Van P H, Schinder A F, Christie B R, et al. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus[J]. Nature, 2002, 415(6875):1030-1034.

[59] Aimone J B, Wiles J, Gage F H. Potential role for adult neurogenesis in the encoding of time in new memories[J]. Nature Neuroscience, 2006, 9(6):723-727.

[60] Snyder J S, Hong N S, Mcdonald R J, et al. A role for adult neurogenesis in spatial long-term memory[J]. Neuroscience, 2005, 130(4):843-852.

[61] Zhang C L, Zou Y, He W, et al. A role for adult TLX-positive neural stem cells in learning and behaviour.[J]. Nature, 2008, 451(451):1004-1007.

[62] Clelland C D, Choi M, Romberg C, et al. A Functional Role for Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Spatial Pattern Separation[J]. Science, 2009, 325(5937):210-213.

[63] Choi S H, Veeraraghavalu K, Lazarov O, et al. Non-Cell-Autonomous Effects of Presenilin 1 Variants on Enrichment-Mediated Hippocampal Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Differentiation[J]. Neuron,2008, 59(4):568-580.

[64] Lazarov O, Marr R A. Neurogenesis and Alzheimer’s disease: at the crossroads[J]. Experimental Neurology, 2010, 223(2):267-281.

[65] Haughey N J, Nath A, Chan S L, et al. Disruption of neurogenesis by amyloid β‐peptide, and perturbed neural progenitor cell homeostasis, in models of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2003, 83(6):1509-1524.

[66]Rodríguez J J, Jones V C, Tabuchi M, et al. Impaired adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Plos One, 2008, 3(8):e2935.

[67] Demars M, Hu Y S, Gadadhar A, et al. Impaired neurogenesis is an early event in the etiology of familial Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic mice[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 2010, 88(10):2103-2117.

[68] Sun B, Halabisky B, Zhou Y, et al. Imbalance between GABAergic and Glutamatergic Transmission Impairs Adult Neurogenesis in an Animal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2009, 5(6):624-633.

[69] Zeng Q, Zheng M, Zhang T, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis in the APP/PS1/nestin-GFP triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Neuroscience, 2016, 314:64-74.

[70] Brinton R D, Wang J M. Therapeutic potential of neurogenesis for prevention and recovery from Alzheimer’s disease: allopregnanolone as a proof of concept neurogenic agent[J]. Current Alzheimer Research, 2006, 3(3):185-190.

[71] Laske C, Stellos K, Stransky E, et al. Decreased plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of stem cell factor in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Journal of Alzheimers Disease, 2008, 15(3):451-460.

[72] Li D, Tang J, Xu H, et al. Decreased hippocampal cell proliferation correlates with increased expression of BMP4 in the APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Hippocampus, 2008, 18(7):692-698.

[73] Taniuchi N, Niidome T, Goto Y, et al. Decreased proliferation of hippocampal progenitor cells in APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice[J]. Neuroreport, 2007, 18(17):1801-1805.

[74] Demars M, Hu Y S, Gadadhar A, et al. Impaired neurogenesis is an early event in the etiology of familial Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic mice.[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 2010, 88(10):2103-2117.

[75] Ghosal K, Stathopoulos A, Pimplikar S W. APP Intracellular Domain Impairs Adult Neurogenesis in Transgenic Mice by Inducing Neuroinflammation[J]. Plos One, 2010, 5(7):e11866.

[76] Wang J M, Singh C, Liu L, et al. Allopregnanolone reverses neurogenic and cognitive deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 107(14):6498-6503.

The Application and Research Progress of the Role of APP in Neurogenesis and Alzheimer’s Disease

ZHU Hongmei1ZHANG Fenglan1CHEN Fang3*XIAO Zhicheng1,2*

1.Key Laboratory of Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine of Yunnan Province, Institute of Molecular and Clinical Medicine, Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650500, China; 2. Immunology and Stem Cell Laboratory, Monash University, Melbourne 3800, Australia;3.School of Basic Medicine, Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650500, China

Alzheimer disease, commonly known as Dementia, was first discovered by German surgon Alzheimer. But this Dementia is different from normal aging. It’s a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disease. Since the discovery of the disease in 1906, its precise pathogenesis has not been completely defined, there is also no an accurate method for early diagnosis and effective treatment.In recent years, a number of studies have confirmed that neurogenesis occurs throughout the central nervous system of adult mammals, which provides hope for the treatment of brain injuries and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD.The study of adult neurogenesis will be great significance for the repair of clinical brain injury and the treatment of AD and other diseases.The article reviewed the process of the central nervous system of adult neurogenesis and the role of APP which is a key molecule involved in pathological process of AD,and summarize its current progress as reference for research.

Amyloid Precursor Protein; Neurogenesis; Alzheimer Disease

朱红梅(1990-),女,汉族,硕士研究生在读,研究方向为神经退行性疾病。E-mail:15288180973@163.com

肖志成(1957-),男,汉族,博士后,教授,研究方向为神经分子生物学。E-mail:zhicheng.xiao@monash.edu

陈 芳(1982-),女,汉族,双学位,讲师,研究方向为基础医学、分子生物学。E-mail:45972141@qq.com

R747.8

A

1007-8517(2017)12-0074-07

2017-05-25 编辑:陶希睿)