直接抗病毒药物对慢性丙型肝炎特殊人群的治疗进展

2017-05-13李元元史继静王福生

李元元,史继静,黄 磊,王福生

直接抗病毒药物对慢性丙型肝炎特殊人群的治疗进展

李元元,史继静,黄 磊,王福生

目前最新的口服直接抗病毒药物不再依赖于干扰素和利巴韦林,该类药对HCV治疗的有效率高达90%以上,这使得丙型肝炎(丙肝)成为可治愈的疾病。然而,在真实世界中,HCV感染的特殊人群(包括合并HIV、HBV共感染,肝移植、肝硬化、肾功能不全以及孕妇、儿童、老人等)的治疗有效率是偏低的,这对口服直接抗病毒药物提出挑战,解决这些挑战最好的办法是了解并掌握药物之间可能存在的风险,从而使更多丙肝特殊人群受益。

丙型肝炎病毒;慢性丙型肝炎;直接抗病毒药物;特殊人群

目前全球慢性HCV感染人群超过1.8亿人[1],持续HCV感染20年会导致16%的感染者出现肝硬化,一旦肝硬化出现,每年就有3%~5%的人群可能发展为肝癌(hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC)[2]。直接抗病毒(direct-acting antivirals, DAA)药物的出现,对慢性丙型肝炎(chronic hepatitis C, CHC)的治疗起到质的飞跃。全球各地提供的DAA治疗CHC患者的数据表明,治疗后出现持续病毒学应答(sustained viral response, SVR)率高达90%~95%,而药物本身的安全性和良好的耐受性使更多的CHC患者从中获益[3-4]。然而在临床上,CHC患者可能是孕妇、儿童、老年人,也可能已合并失代偿期肝硬化、HCC或者其他疾病,如HIV、HBV感染,肾功能不全等情况,那么这部分特殊人群该如何治疗?合并用药该怎么解决?针对这些问题,本文汇总了目前DAA对于CHC特殊人群治疗的临床研究进展。

1 目前常用DAA药物

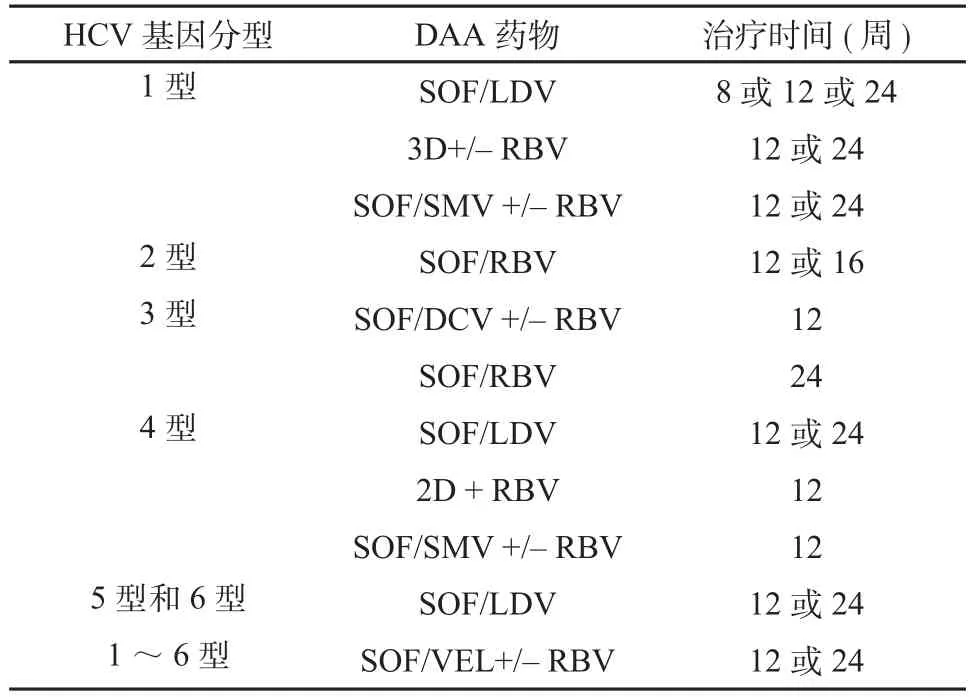

DAA药物根据作用靶点不同分为4类,包括NS3/4A蛋白酶抑制剂、NS5A抑制剂、NS5B聚合酶核苷类似物和非核苷类似物抑制剂。目前常用的NS3/4A蛋白酶抑制剂有simeprevir、paritaprevir、grazoprevir、asunaprevir;NS5A抑制剂有ledipasvir、daclatasvir、ombitasvir、elbasvir、velpatasvir;NS5B聚合酶核苷类似物抑制剂有sofosbuvir;NS5B聚合酶非核苷类似物抑制剂dasabuvir、beclobuvir。2010年的临床试验证明了不使用干扰素和ribavirin,只用2种DAA联合治疗CHC患者也能清除HCV[5],所以目前HCV抗病毒治疗均为2种或2种以上的DAA药物联合治疗(目前常用治疗方案见表1),同时为减少治疗时间和费用,也可联合ribavirin治疗[3]。目前最常见的组合是以sofosbuvir为主,包括sofosbuvir和ledipasvir的共同制剂(harvoni,国内简称吉二代),sofosbuvir和velpatasvir共同制剂(epclusa,国内简称吉三代),sofosbuvir和simeprevir或者daclatasvir等。除此之外,还有2D和3D药物,3D由ritonavir与ABT-450(paritaprevir)(简称ABT-450/r)、ABT-267(ombitasvir)以及ABT-333(dasabuvir)组成,主要针对HCV基因1型的患者。2D由ABT-450/r和ABT-267(ombitasvir)组成,该组合联合ribavirin主要治疗HCV基因4型患者[6]。目前DAA药物疗程大多数为12周,而HCV基因1型的初治CHC患者,如果其HCV RNA <6×106IU/ml,疗程可缩减至8周,但对于肝硬化、既往治疗失败以及HCV基因3型等患者疗程须要延长至24周[7]。

表1 目前推荐的DAA药物组合Table 1 Recommended DAA combinations

2 DAA治疗特殊人群

2.1 HCV合并其他病毒感染

2.1.1 DAA治疗HIV/HCV共感染患者 目前全球已有多项DAA药物治疗HIV/HCV共感染的临床试验。研究数据表明,只要避免了DAA与抗反转录病毒(anti-retroviral, ARV)药物之间的相互作用(drug-drug interactions, DDI),DAA治疗HIV/ HCV共感染与治疗单纯HCV感染人群在疗效和药物耐受性上是相同的[8-9]。这两类药物的DDI主要是通过CYP450同工酶减少或增加某类药物在体内的暴露量(药物在体内作用的时间和强度)导致的[10]。目前HIV/HCV共感染人群使用的DAA药物主要如下。

Sofosbuvir:sofosbuvir与ARV药物同时使用是比较安全的。当然,与tenofovir和HIV蛋白酶抑制剂使用时会增加tenofovir的暴露量,从而发生肾小管病的风险会增高[11],所以同时使用期间建议定期检测尿糖、尿磷酸和尿蛋白[12]。而harvoni与efavirenz、rilpivirine、raltegravir/ dolutegravir同时使用也是安全的[13]。

Daclatasvir:该药是CYP3A4和P-gp的底物,并且抑制转运蛋白OATP1/3和P-gp[14],所以使用ritonavir增强的HIV蛋白酶抑制剂会增加daclatasvir的暴露量。研究显示,daclatasvir与atazanavir/ritonavir同时使用,会使atazanavir暴露量增加2倍,而对darunavir/ritonavir和lopinavir/ritonavir影响不大。因此,当daclatasvir与atazanavir/ritonavir共同使用时,daclatasvir的日剂量必须减少一半(30 mg /d),而与darunavir/ ritonavir和lopinavir/ritonavir同时使用时,不用调整剂量[15]。

3D:因为在3D药物中已经含有100 mg的ritonavir,所以同时使用HIV蛋白酶抑制剂时不须再用ritonavir。联合用药时,efavirenz和rilpivirine在体内的暴露量分别会增加200%和150%,所以应避免3D与这些药物联合治疗;Cobicistat对CYP450酶有很强的抑制作用,所以elvitegravir / cobicistat复合片也要避免与3D药物同时使用;Dolutegravir与3D联合使用是安全的[16-17];3D、atazanavir和ribavirin可以联合使用,不过研究表明,上述药物联合治疗中,患者发生黄疸的风险会增加,特别是合并有Gilbert综合征的患者[18]。

Simeprevir:该药可以与raltegravir、dolutegravir、rilpivirine和tenofovir同时使用[16]。

2.1.2 DAA治疗HBV/HCV共感染患者 HBV和HCV是导致全球慢性病毒性肝炎最常见的病因,同时由于这两种病毒有着相同的传播途径,所以HBV和HCV共感染并不罕见[19]。HBV/HCV患者由于感染双重病毒,因而出现终末期肝病、失代偿期肝硬化以及HCC的风险会增加,所以一定要及时治疗[20]。目前,对于HBV/HCV共感染患者的治疗没有具体的指南,但可以应用治疗HCV或HBV单个感染的指南。对于HCV抗体阳性但多次检测血清HCV RNA为阴性的患者,目前认为HCV感染已治愈,如果须要抗HBV治疗,不用担心HCV可能会复发[21]。而对于HBsAg阳性且多次检测血清HBV DNA阴性的CHC患者(HCV RNA定量阳性),如果治疗HCV并出现SVR后,血清HBV DNA可能会出现阳性[22]。因此,在对HCV进行抗病毒治疗时,必须定期检查HBV DNA,如HBV DNA出现反弹,可以考虑对HBV进行抗病毒治疗[23]。所以临床医生在治疗该类患者时,在用药期间应注意监测两种病毒的变化。目前对于DAA药物治疗合并有HBsAg阴性/抗HBc阳性的CHC患者,HBV再激活的情况并不清楚。

2.2 DAA治疗失代偿期肝硬化、HCC以及肝移植患者

2.2.1 失代偿期肝硬化 肝脏功能严重受损时,肝脏代谢药物的能力也会下降,因此,在患有中度至重度肝硬化的HCV患者中,一些药物的暴露量会增加,导致肝毒性和肝病加重的风险增加。2016年欧洲肝病学会丙型肝炎治疗指南中已明确指出NS3/4A蛋白酶抑制剂不能用于Child-Pugh B或C级失代偿期肝硬化患者。目前已获批治疗失代偿期肝硬化的方案有两种,药物均为NS5A、NS5B抑制剂——harvoni以及daclatasvir加sofosbuvir,合用或不合用ribavirin,疗程分别为12周或24周,两种方案对HCV基因1型和4型治疗均有效,daclatasvir加sofosbuvir也可用于治疗HCV基因3型[4,24]。这些方案对于失代偿期肝硬化患者是安全并且有效的,但要注意使用上述药物时,需患者肌酐清除率>30 ml/min,这个要求与sofosbuvir的药物代谢有关。大多数肝硬化Child-Pugh B或C患者经过治疗后会改善Child-Pugh以及终末期肝病(MELD)的评分。最近获批的epclusa药物在治疗失代偿性肝硬化Child-Pugh B患者的Ⅲ期临床试验中也观察到类似的结果[25]。然而,少数失代偿期肝硬化患者虽然达到了SVR12,但肝功能仍然会恶化,所以,我们需要更长时间的随访数据,便于明确病毒清除后患者肝病仍然恶化的因素,从而更好地制定该类患者的治疗方案。

2.2.2 HCC 既往HCV相关肝硬化患者使用干扰素为基础的治疗达到SVR后,发生HCC的风险会下降[26]。但是,DAA治疗HCV肝硬化患者发生HCC后,两个临床试验的数据出现了相反的结果,一项试验结果是HCC的复发率增加[27],另一项是没有增加[28]。当然,在一项大型研究中,随访DAA治疗失代偿期肝硬化患者达到SVR后发生HCC的风险仍然是下降的[29]。所以,DAA治疗HCC患者的疗效仍然需要大样本以及长期随访数据来说明。

2.2.3 肝移植 肝移植治疗后的HCV患者如果出现病情复发,那么发展为终末期肝病的风险就会增加,数据表明,肝移植术后25%的HCV患者在5年内可发展为肝硬化[30]。因此这类人群进行抗病毒治疗是非常必要的,肝移植术后最常用的免疫抑制剂是cyclosporine和tacrolimus,而这两个药物与目前大多数的DAA有明显的DDI[16]。Simeprevir和daclatasvir只会略微增加cyclosporine和tacrolimus的暴露量,而sofosbuvir不会明显改变cyclosporine和tacrolimus的暴露量。同时,cyclosporine对simeprevir、daclatasvir和sofosbuvir暴露量的影响分别是轻微增加、增加40%以及>4.5倍。Tacrolimus仅轻微增加sofosbuvir暴露,不会改变simeprevir或daclatasvir的浓度[16]。对于HCV基因1型的肝移植患者,病情复发后可以使用3D治疗,但治疗前后要定期进行钙调磷酸酶抑制剂药物的检测,同时为了对抗ritonavir对CYP450抑制作用,须将tacrolimus和cyclosporine的用量分别调整到正常用量的1/10(0.5 mg/7 d或者0.2 mg/72 h)和1/5[31],使用期间须要密切监测tacrolimus、cyclosporine的血药浓度,根据相应的血药浓度进行用量调整。目前,大多数专家认为在等待肝移植的候选者中肝功能损伤相对较轻的患者应尽早使用DAA药物治疗,而对于终末期肝病的患者,等肝移植术后再予以DAA药物治疗。

2.3 DAA治疗肾功能不全和血液透析患者 在临床上,如果肾功能不全患者合并有肝脏疾病,那么因药物暴露量增加而引起的毒性反应主要见于肾功能中度(肌酐清除率31~60 ml / min)和重度(肌酐清除率<30 ml / min)不全患者,很少见于轻度(肌酐清除率61~90 ml / min)患者。对于肾功能不全合并有HCV感染的患者,在使用sofosbuvir、ribavirin、paritaprevir和dasabuvir时,须要适当减少用药剂量,谨慎用药[32]。而simeprevir和daclatasvir主要通过粪便排出,并且在严重肾功能不全的患者中暴露量仅分别增加62%和24%,同时ombitasvir在肾功能不全患者体内暴露量无明显变化,所以,对于HCV基因1型的重度肾功能不全患者,3D药物可能更加适合[33]。最近,在美国和瑞士被批准上市的grazoprevir和elbasvir组合也可以用于肾功能不全的患者,包括终末期肾脏疾病以及须要透析的患者[34]。

2.4 DAA治疗孕妇、儿童及老年人

2.4.1 孕妇 目前临床观察发现除了有肝硬化的孕妇,一般CHC孕妇在怀孕和分娩后没有任何不良情况发生,所以对于CHC孕妇的抗病毒治疗一般都放在分娩之后进行[35]。如果在使用DAA药物治疗期间,女性患者发现怀孕,首先要注意服用的药物是否有潜在致畸性,特别是ribavirin必须马上被停用,因为它会干扰胚胎发育(X类)。simeprevir虽然目前没有人类的数据,但是在动物胎儿模型中已发生不良反应(C类),仍须要停用。对于其他DAA药物,如sofosbuvir和/或ledipasvir,动物胎儿模型没有发现任何风险,属于B类药物。

2.4.2 儿童 儿童HCV感染率一般较低,大多数感染原因是垂直传播和医源性暴露感染,包括输血和透析[36]。通过母亲感染HCV的新生儿大多数在出生后2年内自发清除了HCV,同时,被HCV感染的儿童比成人病情进展速度慢,所以儿童期发生丙型肝炎肝硬化是非常罕见的[37]。虽然对于年龄小于3岁的儿童不推荐进行抗病毒治疗,但对于存在重度纤维化和/或严重肝外表现的大龄儿童,可以考虑治疗,目前相关临床试验正在进行中[38]。

2.4.3 老年人 对于HCV感染的老年患者,其治疗方案必须评估,包括治疗后预期效益、药物可能的不良反应以及药物相互作用风险等[39]。近期已有报道发出警告,HCV老年患者使用DAA后出现了心动过缓、低血糖等不良反应[40]。所以,一些DAA药物临床试验设定入组患者年龄为80岁以下,同时国际指南(AASLD/IDSA和EASL)也指出,80岁以上的HCV患者考虑其有限的预期寿命,不建议抗病毒治疗。所以,成本效益、预期寿命以及合并症是指导今后老年HCV患者治疗的关键点[41]。

3 总 结

DAA药物的出现,使CHC成为一种可治愈的疾病,而感染HCV的特殊人群成为DAA治疗过程中的挑战。如何更好的使这部分人群受益依赖于对药物相互作用的了解,可能存在风险的预估以及治疗成本效益的评估。总之,掌握特殊人群的治疗,最终会使更多患者受益。

[1] Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of agespecific antibody to HCV seroprevalence[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 57(4):1333-1342.

[2] Bruix J, Sherman M, American Association for the Study of Liver D. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update[J]. Hepatology, 2011, 53(3):1020-1022.

[3] European Association for Study of Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2015[J]. J Hepatol, 2015, 63(1):199-236.

[4] AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 62(3):932-954.

[5] Gane EJ, Roberts SK, Stedman CA, et al. Oral combination therapy with a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor (RG7128) and danoprevir for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection (INFORM-1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial[J]. Lancet, 2010, 376(9751):1467-1475.

[6] Hezode C, Asselah T, Reddy KR, et al. Ombitasvir plus paritaprevir plus ritonavir with or without ribavirin in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C virus infection (PEARL-I): a randomised, open-label trial[J]. Lancet, 2015, 385(9986):2502-2509.

[7] Conjeevaram H. Continued progress against hepatitis C infection[J]. JAMA, 2015, 313(17):1716-1717.

[8] Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M, et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(8):705-713.

[9] Sulkowski MS, Eron JJ, Wyles D, et al. Ombitasvir, paritaprevir co-dosed with ritonavir, dasabuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients co-infected with HIV-1: a randomized trial[J]. JAMA, 2015, 313(12):1223-1231.

[10] Jimenez-Nacher I, Alvarez E, Morello J, et al. Approaches for understanding and predicting drug interactions in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients[J]. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2011, 7(4):457-477.

[11] Sofia MJ. Beyond sofosbuvir: what opportunity exists for a better nucleoside/nucleotide to treat hepatitis C[J]. Antiviral Res, 2014, 107:119-124.

[12] Labarga P, Barreiro P, Martin-Carbonero L, et al. Kidney tubular abnormalities in the absence of impaired glomerular function in HIV patients treated with tenofovir[J]. AIDS, 2009, 23(6):689-696.

[13] Osinusi A, Townsend K, Kohli A, et al. Virologic response following combined ledipasvir and sofosbuvir administration in patients with HCV genotype 1 and HIV co-infection[J]. JAMA, 2015, 313(12):1232-1239.

[14] Aghemo A, De Francesco R. Daclatasvir: a team player rather than a prima donna in the treatment of hepatitis C[J]. Gut, 2015, 64(6):860-862.

[15] Wyles DL, Ruane PJ, Sulkowski MS, et al. Daclatasvir plus Sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(8):714-725.

[16] Soriano V, Labarga P, Barreiro P, et al. Drug interactions with new hepatitis C oral drugs[J]. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2015, 11(3):333-341.

[17] Esposito I, Labarga P, Barreiro P, et al. Dual antiviral therapy for HIV and hepatitis C-drug interactions and side effects[J]. Expert Opin Drug Saf, 2015, 14(9):1421-1434.

[18] Gentile I, Borgia F, Buonomo AR, et al. ABT-450: a novel protease inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection[J]. Curr Med Chem, 2014, 21(28):3261-3270.

[19] Caccamo G, Saffioti F, Raimondo G. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus dual infection[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(40):14559-14567.

[20] Soriano V, Barreiro P, Martin-Carbonero L, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B or C in HIV-infected patients with dual viral hepatitis[J]. J Infect Dis, 2007, 195(8):1181-1183.

[21] Fernandez-Montero JV, Soriano V. Management of hepatitis C in HIV and/or HBV co-infected patients[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2012, 26(4):517-530.

[22] Collins JM, Raphael KL, Terry C, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation during successful treatment of hepatitis C virus with sofosbuvir and simeprevir[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2015, 61(8):1304-1306.

[23] Soriano V, Labarga P, de Mendoza C, et al. Emerging challenges in managing hepatitis B in HIV patients[J]. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 2015, 12(3):344-352.

[24] Hjerrild S, Dalgard O, Christensen PB, et al. Debilitating fatigue as a treatment indication in chronic hepatitis C[J]. J Hepatol, 2015, 63(6):1533-1534.

[25] Curry MP, O´Leary JG, Bzowej N, et al. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(27):2618-2628.

[26] van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis[J].JAMA, 2012, 308(24):2584-2593.

[27] Reig M, Marino Z, Perello C, et al. Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy[J]. J Hepatol, 2016, 65(4):719-726.

[28] ANRS collaborative study group on hepatocellular carcinoma (ANRS CO22 HEPATHER, CO12 CirVir and CO23 CUPILT cohorts). Lack of evidence of an effect of direct-acting antivirals on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: Data from three ANRS cohorts[J]. J Hepatol, 2016, 65(4):734-740.

[29] Foster GR, Irving WL, Cheung MC, et al. Impact of direct acting antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and decompensated cirrhosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2016, 64(6):1224-1231.

[30] Stock PG, Terrault NA. Human immunodeficiency virus and liver transplantation: Hepatitis C is the last hurdle[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 61(5):1747-1754.

[31] Badri P, Dutta S, Coakley E, et al. Pharmacokinetics and dose recommendations for cyclosporine and tacrolimus whencoadministered with ABT-450, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir[J]. Am J Transplant, 2015, 15(5):1313-1322.

[32] Kwo PY, Badshah MB. New hepatitis C virus therapies: drug classes and metabolism, drug interactions relevant in the transplant settings, drug options in decompensated cirrhosis, and drug options in end-stage renal disease[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2015, 20(3):235-241.

[33] Gentile I, Buonomo AR, Borgia G. Ombitasvir: a potent pangenotypic inhibitor of NS5A for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection[J]. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 2014, 12(9):1033-1043.

[34] Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study[J]. Lancet, 2015, 386(10003):1537-1545.

[35] Beste LA, Bondurant HC, Ioannou GN. Prevalence and management of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in women[J]. Med Clin North Am, 2015, 99(3):575-586.

[36] Toussaint-Miller KA, Andres J. Treatment considerations for unique patient populations with HCV genotype 1 infection[J]. Ann Pharmacother, 2015, 49(9):1015-1030.

[37] Iorio R, Giannattasio A, Sepe A, et al. Chronic hepatitis C in childhood: an 18-year experience[J]. Clin Infect Dis , 2005, 41(10):1431-1437.

[38] Serranti D, Indolfi G, Resti M. New treatments for chronic hepatitis C: an overview for paediatricians[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(43):15965-15974.

[39] Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Galati G, Gallo P, et al. Hepatitis C treatment in the elderly: new possibilities and controversies towards interferon-free regimens[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(24):7412-7426.

[40] Renet S, Chaumais MC, Antonini T, et al. Extreme bradycardia after first doses of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir in patients receiving amiodarone: 2 cases including a rechallenge[J]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 149(6):1378-1380e1371.

[41] Bickerstaff C. The cost-effectiveness of novel direct acting antiviral agent therapies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C[J]. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res, 2015, 15(5):787-800.

(2017-03-14收稿 2017-04-10修回)

(本文编辑 闫晶晶)

Treatment progress of chronic hepatitis C with direct-acting antivirals in special populations

LI Yuan-yuan, SHI Ji-jing, HUANG Lei, WANG Fu-Sheng*

Treatment and Research Center for Infectious Diseases, 302 Military Hospital of China, Beijing 100039, China

With the latest all-oral interferon and ribavirin-free regimens based on direct acting antivirals against the HCV, sustained virological response rates of>90% are achieved, which is equivalent to cure. However, outcomes in special patients with HCV infection tend to be lower and treatment of special patients is often challenging, such as HIV-positive persons, transplant recipients, patients with advanced cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, HBV coinfection, pregnancy, children and older patients. The best way to solve these challenges relies on understanding the potential risks of drug interactions, so as to be of benefits to more special populations with hepatitis C.

hepatitis C virus; chronic hepatitis C; direct-acting antivirals; special populations

R512.63

A

1007-8134(2017)02-0070-05

10.3969/j.issn.1007-8134.2017.02.002

国家自然科学基金(81601731)

100039 北京,解放军第三〇二医院感染性疾病诊疗与研究中心(李元元、史继静、黄磊、王福生)

王福生,E-mail: fswang302@163.com

*Corresponding author, E-mail: fswang302@163.com