Heterogeneous populations of neural stem cells contribute to myelin repair

2017-05-03rainerAkkermannFelixBeyerpatrickry

rainer Akkermann, Felix Beyer, patrick Küry

Neuroregeneration Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Medical Faculty, Heinrich-Heine-University, Düsseldorf, Germany

Heterogeneous populations of neural stem cells contribute to myelin repair

rainer Akkermann, Felix Beyer, patrick Küry*

Neuroregeneration Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Medical Faculty, Heinrich-Heine-University, Düsseldorf, Germany

How to cite this article:Akkermann R, Beyer F, Küry P (2017) Heterogeneous populations of neural stem cells contribute to myelin repair. Neural Regen Res 12(4):509-517.

Open access statement:This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Funding:The German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) supported RA. This work was also supported by grants to PK by the German Research Council (DFG; SPP1757/KU1934/2_1, KU1934/5-1), the Christiane and Claudia Hempel Foundation for clinical stem cell research and YoungGlia. The MS Center at the Department of Neurology is supported in part by the Walter and Ilse Rose Foundation and the James and Elisabeth Cloppenburg, Peek & Cloppenburg Düsseldorf Foundation.

As ingenious as nature’s invention of myelin sheaths within the mammalian nervous system is, as fatal can be damage to this specialized lipid structure. Long-term loss of electrical insulation and of further supportive functions myelin provides to axons, as seen in demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), leads to neurodegeneration and results in progressive disabilities. Multiple lines of evidence have demonstrated the increasing inability of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) to replace lost oligodendrocytes (OLs) in order to restore lost myelin. Much research has been dedicated to reveal potential reasons for this regeneration def i cit but despite promising approaches no remyelination-promoting drugs have successfully been developed yet. In addition to OPCs neural stem cells of the adult central nervous system also hold a high potential to generate myelinating OLs.ere are at least two neural stem cell niches in the brain, the subventricular zone lining the lateral ventricles and the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus, and an additional source of neural stem cells has been located in the central canal of the spinal cord. While a substantial body of literature has described their neurogenic capacity, still little is known about the oligodendrogenic potential of these cells, even if some animal studies have provided proof of their contribution to remyelination. In this review, we summarize and discuss these studies, taking into account the different niches, the heterogeneity within and between stem cell niches and present current strategies of how to promote stem cell-mediated myelin repair.

heterogeneity; oligodendrocyte; neuroregeneration; multiple sclerosis; inhibitors; intracellular protein localization; adult neural stem cell niche; remyelination

Introduction

Neural Stem Cells as a Pool for Myelin Repair

Pluripotent stem cells reside in many tissues of the body to replace cells lost due to homeostasis or damage. Usually known for their ability to generate neurons, NSCs, the stem cells of the CNS, can also give rise to glial cells (Lois andAlvarez-Buylla, 1993; Seri et al., 2001; Rivera et al., 2010). NSCs are derived from radial glial cells during embryonic development and subsequently divide asymmetrically to self-renew and produce progeny that undergo differentiation and migration (Calzolari et al., 2015). In the subventricular zone (SVZ), lining the lateral ventricles, NSCs (also referred to as SVZ astrocytes or type B cells) that become activated generate transit-amplifying progenitors (TAPs or type C cells), which can differentiate into neuroblasts (type A cells) or glial cells (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1994; Carleton et al., 2003). Neurons derived from the SVZ usually migrate along the rostral migratory stream to the olfactory bulb in mammals or to the striatum in humans, whereas OLs mostly populate the adjacent corpus callosum (Seri et al., 2006).e subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampus, located at the interface of the granule cell layer and the hilus in the dentate gyrus, also harbors NSCs (also referred to as SGZ astrocytes) producing progeny termed type D cells (Seri et al., 2004).ese cells divide, thereby giving birth to further progenitors and eventually produce new granular neurons that are incorporated into the granular layer of the dentate gyrus (Laywell et al., 2000).

Strategies for the Promotion of NSC-Mediated Myelin Repair

Whilst stem cell transplantation has so far mainly been considered for the treatment of aggressive forms of demyelinating diseases, primarily addressing trophic- and immunomodulatory properties of haematopoietic- or mesenchymal stem cells (Jadasz et al., 2012a), a feasible and straightforward alternative is the pharmacological activation of endogenous stem cells. A small but growing body of literature has demonstrated that NSCs can be manipulated to increase their oligodendrogenic potential. One week following viral-mediated forced overexpression of the major oligodendroglial transcription factor Olig2 in the SVZ, 50% of infected cells were found to have migrated into the corpus callosum and acquired an oligodendroglial identity, at the expense of neuronal precursor numbers (Hack et al., 2005). Similarly, nestin-mediated ectopic expression of Olig2 (but not Olig1) also led to a significant increase in SVZ NSC-derived OL numbers with a concomitant 10% increase of myelinated axons in the corpus callosum (Maire et al., 2010). Also in the SGZ, reprogramming of NSCs towards an oligodendroglial fate was shown by ectopic overexpression of Ascl1/Mash1, and these cells are capable of remyelinating an experimentally induced demyelinated lesion in the hippocampus (Jessberger et al., 2008; Braun et al., 2015). NSC-derived OL densities are also boosted upon intraventricular infusion of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3β) inhibitors, which induce the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, leading to enhanced myelination in development as well as a promotion of remyelination in response to focal demyelination (Azim and Butt, 2011; Azim et al., 2014b). A recent study has presented a valuable tool for the identif ication of small molecules that may be used for instructing fate decisions in stem cells (Azim et al., 2017). Followingin silicogenomic analysis using the searchable platform-independent expression database/connectivity map (SPIED/ CMAP), it could be shown that intraventricular infusion of LY-294002, a PI3K/Akt inhibitor, promotes oligodendrogenesis at the expense of neurogenesis in the dorsal SVZ and signif i cantly enhances myelination (Azim et al., 2017). Using the same approach, the group identified another GSK3β inhibitor, CHIR99021, which following intranasal delivery in hypoxic animals results in elevated densities of OLs able to produce myelin (Azim et al., 2017). Thus, the SPIED/CMAP database allows for the identif i cation of upstream molecules that may be used to activate or inhibit pathways of interest, thereby enabling to quickly and easily determine potential drugs for the treatment of diseases. Importantly, as observed in post-mortem tissue, NSC recruitment and oligodendrogenesis was also shown to occur in brains of aged MS patients (Nait-Oumesmar et al., 2007). Together, these fi ndings suggest that NSCs in human neurogenic niches could be pharmacologically stimulated in order to acquire an oligodendrogenic fate and thus to contribute to myelin repair.

Potential candidate small molecules can then be thoroughly tested in different experimental models, including toxic demyelination models but also models comprising an autoimmune component, such as in EAE, also addressing the most efficient type of administration. Moreover, it would be desirable to determine whether a combination of the identified small molecule together with approved immunomodulatory drugs can yield synergistic regenerative and anti-inf l ammatory ef f ects. Ideally, suitable small molecules will be able to induce and boost the activation of endogenous NSCs in their niches, that is their production of migratory progenitors capable of populating demyelinated lesions and their subsequent differentiation into myelinating OLs. Based on differences/similarities between NSC-derived and parenchymal OPCs, it will be important to determine whether the small molecules of choice also exert a pro-oligodendroglial differentiation effect on parenchymal OPCs, in which case the benef i cial outcome could be additive.

Ef f ect of Aging on NSC Oligodendrogenesis

Heterogeneity of NSCs and its Implications for Oligodendrogenesis

The degree of heterogeneity between different populations of NSCs becomes apparent based on the various types of neurons they generate. For example, SVZ NSCs give rise to neuroblasts that migrate to the olfactory bulb to replace GABAergic interneurons (Figure 1) (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1994; Carleton et al., 2003), whereas the progeny of SGZ NSCs differentiate into new glutamatergic granular neurons which integrate into the granular layer of the dentate gyrus (Figure 2) (Laywell et al., 2000).erefore, NSC heterogeneity appears to be attributed to different regional requirements but also to be influenced by the local environment. Importantly, NSCs are not only heterogeneous regarding neurogenesis but also regarding oligodendrogenesis. In order to efficiently activate NSCs for the improvement of myelin regeneration, it will be important to understand the distinct oligodendrogenic capacities of different NSC subpopulations. On the other hand, shared pathways and properties may enable simultaneous mobilization to maximize the regenerative ef f ect.

SVZversusSGZ

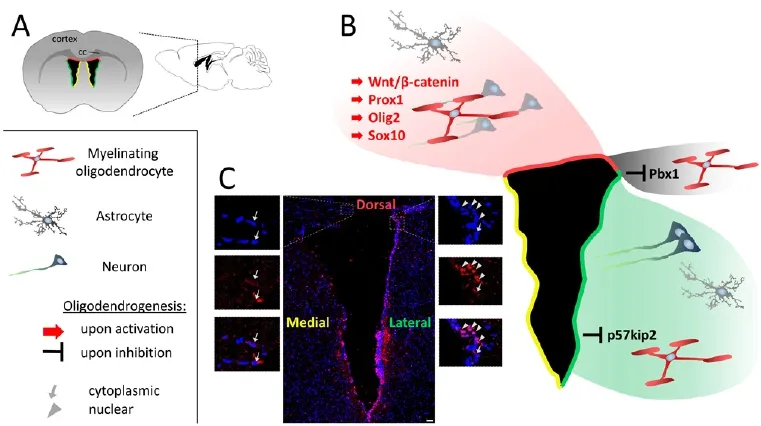

Figure 1 Subventricular zone of the adult brain with relation to glial and neuronal progeny.

Figure 2 Induction of oligodendrogenesis in the subgranular zone of the hippocampus.

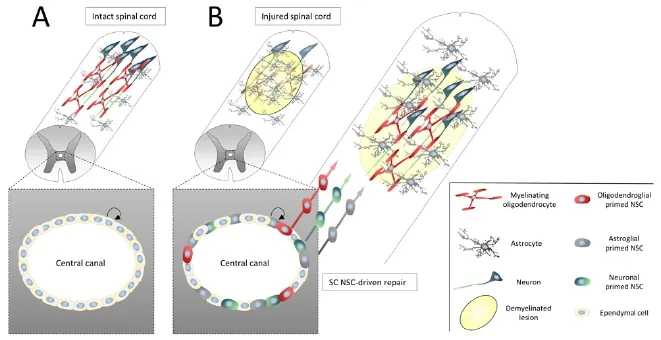

Figure 3 Adult neural stem cells (NSCs) reside within the ependymal cell layer lining the spinal cord central canal.

The most obvious heterogeneity between SVZ- and SGZ NSCs is that the former tissue gives rise to all three CNS lineages (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes) under physiological conditions, whereas the latter tissue appears to generate neurons only, unless genetically modified (Jessberger et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2015) or trophically boosted (Rivera et al., 2006). Indeed, subtle intrinsic regulatory differences might account for these distinct cellular properties and potentials. While promoting neurogenesis in the SGZ (Karalay et al., 2011), the transcription factor prospero-related homeobox 1 gene (Prox1) was found to drive NSC oligodendrogenesis in the SVZ instead (Figures 1B and 2B) (Bunk et al., 2016).is discrepancy suggests fundamental differences in the transcriptional network of these cell populations and this is further supported by another study reporting that Pbx1 is exclusively expressed in the SVZ where it regulates the balance between neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis (Grebbin et al., 2016). Single-cell transcriptome analyses of SVZ- and SGZ NSCs, on the other hand, found positive correlation in gene expression prof i les between these populations, suggesting some conservation at least regarding quiescence and activation in different neurogenic niches (Shin et al., 2015; Dulken et al., 2017). Whilst it was demonstrated that SVZ NSCs have a substantial regenerative and migratory potential following demyelination (Jablonska et al., 2010; Xing et al., 2014; Brousse et al., 2015), it remains unclear whether SGZ NSCs respond to demyelination by producing OLs without being artificially reprogrammed, and whether these cells can migrate to surrounding white matter tracts.

Dorsalversuslateral microdomains of the SVZ

The different embryonic origins of the walls of the lateral ventricle that form the SVZ explain the heterogeneity found within this neurogenic niche (Fiorelli et al., 2015). While the dorsal microdomain stems from the pallium, the lateral and medial walls originate from the lateral and medial ganglionic eminences (LGE and MGE), and the septum, respectively (Fiorelli et al., 2015). SVZ heterogeneity is also ref l ected by distinct transcriptional prof i les which def i ne several different states of NSCs, the two general ones of which are quiescent (associated for example with Sox9, Id2, Id3 and Notch expression) and activated (associated for example with Egr1, Fos, Sox4/11 and Ascl1 expression) (Llorens-Bobadilla et al., 2015), which can even be subdivided further (Dulken et al., 2017).e transcriptional prof i le of NSCs also varies depending on the microdomain within the SVZ, whereby dorsal NSCs are enriched for genes including Emx1 and Tbr2 and the lateral SVZ displays higher expression of markers such as Gsx2 and Dlx2 (Azim et al., 2014a; Llorens-Bobadilla et al., 2015).ese transcriptional signatures correspond to specific neuronal and glial subtypes in NSC progeny. Expression of oligodendroglial transcription factors Olig2 and Sox10 specif i cally in the dorsal SVZ make this domain the default source for oligodendroglial lineage cells (Figure 1B) (Ortega et al., 2013; Azim et al., 2014a, b). Another key regulator of oligodendrogenesis enriched in the dorsal SVZ is Wnt/β-catenin (Ortega et al., 2013; Azim et al., 2014a, b). Ectopical stimulation of this pathwayviaeither infusion of the agonist Wnt3a, its virus-mediated overexpression, or inhibition of GSK3β leads to the induction of oligodendrogenesis from NSCs in this subdomain (Figure 1B) (Ortega et al., 2013; Azim et al., 2014a, b). In line with these findings, Prox1, a target of Wnt signaling, is also predominantly expressed within the dorsal SVZ and is required for NSC oligodendrogenesis (Bunk et al., 2016).is enrichment in pro-oligodendrogenic signaling molecules in the dorsal SVZ reflects its greater capacity to generate OLs as compared with lateral SVZ NSCs. Whether this heterogeneity is based on the simple fact that the dorsal domain is located closer to the corpus callosum – a white matter tract and a pro-oligodendroglial environment – remains to be investigated. It is also important to take into account the spatial component of the SVZ along the rostro-caudal axis, whereby the surface of the dorsal microdomain becomes larger caudally while the lateral wall is more expanded in the rostral as opposed to the caudal region (Fiorelli et al., 2015).erefore, also the density of NSCs within the microdomains varies substantially between these spatial regions (Mirzadeh et al., 2008; Azim et al., 2012).

These heterogeneous profiles of neurogenic- and oligodendrogenic gene expression point towards a fate restriction of specific NSC subpopulations of the SVZ, which occurs early in development and appears to be cell dependent since they do not re-specify when heterotopically transplanted (De Marchis et al., 2007; Merkle et al., 2007; Young et al., 2007). Nevertheless, also the lateral wall of the SVZ can produce OLs and this can be enhanced for instance by lentiviral expression of Wnt3 (Ortega et al., 2013), underlining the great potential of this neurogenic niche for myelin regeneration. Likewise, our own studies on the p57kip2 protein which we identified on the one hand as potent intrinsic inhibitor of OPC differentiation (Kremer et al., 2009), and on the other hand as a fate determinant for NSC-derived oligodendroversusastrogenesis (Jadasz et al., 2012b) also point to a role in microdomain specif i cation. As shown in Figure 1C higher numbers of p57kip2 expressing cells can be observed in the lateral SVZ microdomain, whereas fewer positive cells reside in the dorsal region (Beyer, Akkermann and Küry, unpublished data). To what degree a p57kip2 mediated fate determination and/or a blockade of oligodendroglial maturation account for regional differences in efficiently generating OLs remains to be shown in current experiments. Moreover, in parenchymal OPCs we recently demonstrated that not only the expression of p57kip2 as such but its subcellular localization is responsible for controlling oligodendroglial differentiation. While nuclear p57kip2 proteins exert inhibition, cytoplasmic p57kip2 proteins were found to be neutral or to act as pro-oligodendroglial factors (Göttle et al., 2015), thereby contributing yet another level of heterogeneity which might also be relevant for NSCs (Figure 1C). It also remains to be shown whether the increasingly large number of intrinsic negative regulators identified in parenchymal OPCs (Kremer et al., 2011) also exert an impact on NSCs at different sites within the SVZ, particularly in light of the fact that for some of them biomedical translation has been developed (Kremer et al., 2016).

SGZ subpopulations

Spinal cord NSCs

Another source of NSCs, expressing typical markers such as Sox2, Nestin and Vimentin, resides within the ependymal layer of the central canal of the spinal cord (SC; Figure 3A) (Brundin et al., 2003; Meletis et al., 2008).e most prominent difference between SC NSCs and those located within the brain is that they are mostly quiescent during homeostatic conditions, with low proliferative activity. In contrast, upon SC injury or in response to EAE, these cells become highly proliferative and give rise to neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Figure 3B) (Brundin et al., 2003; Danilov et al., 2006; Meletis et al., 2008; Barnabé-Heider et al., 2010). Interestingly, when heterotopically transplanted into the hippocampus SC NSCs integrated into the granular cell layer and differentiated into neurons typical for this region, indicating that they are not limited to the fate of their origin (Shihabuddin et al., 2000), which is a common feature of SGZ NSCs (Suhonen et al., 1996) but not of SVZ NSCs (De Marchis et al., 2007; Merkle et al., 2007; Young et al., 2007). Following SC injury, the contribution of SC NSCs to the astroglial pool is far greater than to the oligodendroglial pool, which could be due to the great density of parenchymal OPCs that produce myelinating OLs in this model (Barnabé-Heider et al., 2010). However, it was demonstrated that SC NSC-derived OLs myelinated axons in the lesion (Meletis et al., 2008). Importantly, OLs are also generated from SC NSCs in response to EAE aer they (or their progeny) migrated towards demyelinated lesions (Brundin et al., 2003). These are valuable observations with respect to the frequently observed demyelinated lesions in the SCs of MS patients and the failure of OPCs to replenish the pool of myelinating OLs. Since also the human SC appears to harbor NSCs (Cawsey et al., 2015), preferentially also in aged or progressive MS patients, pharmacological activation of these cells may provide a strategy to repair SC lesions by enhancing their oligodendroglial differentiation.

NSCsversusparenchymal oligodendroglial lineage cells

Cells of the oligodendroglial lineage are a heterogeneous population with intrinsic cellular differences depending on age and the region within the CNS (Viganò and Dimou, 2016; Moshrefi-Ravasdjani et al., 2017), a regionalization which is also reflected by differences in gene expression patterns (Marques et al., 2016). For example, in a recent study OPCs isolated from cortex and SC were cultured on microf i bers and the myelin sheaths generated were analyzed. Interestingly, independent of the fiber diameter cells from SC formed myelin sheaths of greater length as compared to cortical cells, indicating intrinsic differences between these two populations (Bechler et al., 2015). To date, little is known to what extent OPCs/OLs derived from NSCs are different from parenchymal oligodendroglial cells. Given the above-described heterogeneity between different NSC populations and parenchymal oligodendroglial lineage cells, it is not unlikely that NSC progeny display distinct properties with respect to migration, process extension, differentiation, myelin wrapping and the number of axons they interact with. Indeed, Xing and colleagues found differences in the quality of the myelin sheaths produced by NSC- as compared to OPC-derived OLs in response to demyelination (Xing et al., 2014). A hallmark of remyelination is that produced myelin sheaths are thinner as compared to internodes generated during development (Gledhill and McDonald, 1977). Remarkably, following cuprizone-induced demyelination, SVZ NSC-derived OLs were found to form myelin sheaths with a thickness indistinguishable from those produced during development (Xing et al., 2014). It will be crucial to determine the mechanisms behind this finding and whether other NSC populations have the same capacity. It will also be of interest to see whether molecules can be identified that enhance this regenerative capacity and to what degree NSC subpopulations show heterogeneous responses towards such stimulation. Whilst a number of factors have been identified which drive oligodendrogenesis in both NSCs as well as parenchymal OPCs a few were found to exert this effect on NSCs exclusively (Akkermann et al., 2016). This disparity in the responsiveness of these two cell populations, possibly ref l ecting differences in certain molecular prof i les and pathways, may account for the heterogeneity in oligodendrogenesis between NSCs and OPCs.

Conclusions

Given the endogenous capacity of NSCs to give rise to new myelinating OLs in response to demyelination, as well as the life-long potential of neurogenic niches for oligodendrogenesis pharmacological stimulation of this process is a promising strategy for the establishment of myelin repair approaches. Moreover, manipulation of NSCs has already been shown to effectively enhance remyelination in different contexts (Akkermann et al., 2016). While one study suggests that NSC progeny is capable of migrating some distances, subsequently taking on a glial fate in the MS brain (Nait-Oumesmar et al., 2007), the scattered and widespread distribution of lesions along great distances in this context still poses a problem in the process of myelin repair, particularly when taking into account the dimensions of the human CNS. Understanding NSC biology, that is their cellular and molecular characteristics and kinetics, particularly under pathological conditions, will help developing new regenerative strategies in the treatment of demyelinating diseases. A vital aspect in this process is the heterogeneity between different NSC populations, both at the intercellular level within subdomains as well as at the molecular level within each stem cell and its progeny.

Author contributions:All authors contributed equally to literature review, text conception, manuscript writing, review of author and reviewer contributions/comments, and manuscript finalization. All authors approved the f i nal version of the manuscript and are listed in alphabetical order.

Conf l icts of interest:None declared.

Aguirre A, Dupree JL, Mangin JM, Gallo V (2007) A functional role for EGFR signaling in myelination and remyelination. Nat Neurosci 10:990-1002.

Akkermann R, Jadasz J, Azim K, Küry P (2016) Taking advantage of nature’s gift: can endogenous neural stem cells improve myelin regeneration? Int J Mol Sci 17:1895.

Azim K, Angonin D, Marcy G, Pierpan F, Rivera A, Donega V, Cantu C, Williams G, Berninger B, Butt AM, Raineteau O, Neurogenesis A (2017) Pharmacogenomic identif i cation of small molecules for lineage specif i c manipulation of subventricular zone germinal activity. PLoS Biol 15:e2000698.

Azim K, Butt AM (2011) GSK3β negatively regulates oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination in vivo. Glia 59:540-553.

Azim K, Fiorelli R, Zweifel S, Hurtado-Chong A, Yoshikawa K, Slomianka L, Raineteau O (2012) 3-dimensional examination of the adult mouse subventricular zone reveals lineage-specific microdomains. PLoS One 7:e49087.

Azim K, Fischer B, Hurtado-Chong A, Draganova K, Cantù C, Zemke M, Sommer L, Butt A, Raineteau O (2014a) Persistent Wnt/β-catenin signaling determines dorsalization of the postnatal subventricular zone and neural stem cell specification into oligodendrocytes and glutamatergic neurons. Stem Cells 32:1301-1312.

Azim K, Rivera A, Raineteau O, Butt AM (2014b) GSK3β regulates oligodendrogenesis in the dorsal microdomain of the subventricular zone via Wnt-β-catenin signaling. Glia 62:778-779.

脑卒中在临床中比较常见,有着较高的致残率,如果没有及时处理,会影响到患者的生活质量和水平。经过相关研究,患者在出现脑卒中之后,相关的中枢神经系统还具备一定的自然恢复功能,具备一定的神经功能。在康复治疗中,需要恢复这些功能,同时利用加速脑侧枝循环的构建,促进侧脑组织或者病灶周围组织的补偿和重组[1] 。所以,使用有效治疗方法和合理康复介入实际可以显著恢复患者的神经功能,改善患者的生活自理能力。在临床康复治疗中,脑梗死患者一般在一周之内,少数的在两天之内,脑出血的患者需要在两周之内介入康复治疗[2] 。

Barnabé-Heider F, Göritz C, Sabelström H, Takebayashi H, Pfrieger FW, Meletis K, Frisén J (2010) Origin of new glial cells in intact and injured adult spinal cord. Cell Stem Cell 7:470-482.

Bechler ME, Byrne L, Ffrench-Constant C (2015) CNS myelin sheath lengths are an intrinsic property of oligodendrocytes. Curr Biol 25:2411-2416.

Bergmann O, Liebl J, Bernard S, Alkass K, Yeung MSY, Steier P, Kutschera W, Johnson L, Landén M, Druid H, Spalding KL, Frisén J (2012)e age of olfactory bulb neurons in humans. Neuron 74:634-639.

Bouab M, Paliouras GN, Aumont A, Forest-Bérard K, Fernandes KJL (2011) Aging of the subventricular zone neural stem cell niche: Evidence for quiescence-associated changes between early and mid-adulthood. Neuroscience 173:135-149.

Braun SMG, Pilz GA, Machado RAC, Becher B, Toni N, Jessberger S, Moss J (2015) Programming hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells into oligodendrocytes enhances remyelination in the adult brain aer injury. Cell Rep 11:1679-1685.

Brousse B, Magalon K, Durbec P, Cayre M (2015) Region and dynamic specif i cities of adult neural stem cells and oligodendrocyte precursors in myelin regeneration in the mouse brain. Biol Open 4:980-992.

Brundin L, Brismar H, Danilov AI, Olsson T, Johansson CB (2003) Neural stem cells: a potential source for remyelination in neuroinfl ammatory disease. Brain Pathol 13:322-328.

Bunk EC, Ertaylan G, Ortega F, Pavlou MA, Gonzalez Cano L, Stergiopoulos A, Safaiyan S, Völs S, van Cann M, Politis PK, Simons M, Berninger B, Del Sol A, Schwamborn JC (2016) Prox1 is required for oligodendrocyte cell identity in adult neural stem cells of the subventricular zone. Stem Cells 34:2115-2129.

Calzolari F, Michel J, Baumgart EV,eis F, Götz M, Ninkovic J (2015) Fast clonal expansion and limited neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult subependymal zone. Nat Neurosci 18:490-492.

Carleton A, Petreanu LT, Lansford R, Alvarez-Buylla A, Lledo PM (2003) Becoming a new neuron in the adult olfactory bulb. Nat Neurosci 6:507-518.

Cawsey T, Duflou J, Shannon Weickert C, Gorrie CA (2015) Nestin-positive ependymal cells are increased in the human spinal cord aer traumatic central nervous system injury. J Neurotrauma 32:1393-1402.

Chang A, Nishiyama A, Peterson J, Prineas J, Trapp BD (2000) NG2-positive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in adult human brain and multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurosci 20:6404-6412.

Chang A, Tourtellotte WW, Rudick R, Trapp BD (2002) Premyelinating oligodendrocytes in chronic lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 346:165-173.

Chetty S, Friedman AR, Taravosh-Lahn K, Kirby ED, Mirescu C, Guo F, Krupik D, Nicholas A, Geraghty AC, Krishnamurthy A, Tsai M-K, Covarrubias D, Wong AT, Francis DD, Sapolsky RM, Palmer TD, Pleasure D, Kaufer D (2014) Stress and glucocorticoids promote oligodendrogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Mol Psychiatry 19:1275-1283.

Chong VZ, Webster MJ, Rothmond DA, Weickert CS (2008) Specif i c developmental reductions in subventricular zone ErbB1 and ErbB4 mRNA in the human brain. Int J Dev Neurosci 26:791-803.

Crawford AH, Tripathi RB, Richardson WD, Franklin RJM (2016) Developmental origin of oligodendrocyte lineage cells determines response to demyelination and susceptibility to age-associated functional decline. Cell Rep 15:761-773.

Danilov AI, Covacu R, Moe MC, Langmoen IA, Johansson CB, Olsson T, Brundin L (2006) Neurogenesis in the adult spinal cord in an experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci 23:394-400.

De Marchis S, Bovetti S, Carletti B, Hsieh YC, Garzotto D, Peretto P, Fasolo A, Puche AC, Rossi F (2007) Generation of distinct types of periglomerular olfactory bulb interneurons during development and in adult mice: implication for intrinsic properties of the subventricular zone progenitor population. J Neurosci 27:657-664.

Dulken BW, Leeman DS, Phane S, Boutet C, Hebestreit K, Brunet Correspondence A, Brunet A (2017) Single-cell transcriptomic analysis def i nes heterogeneity and transcriptional dynamics in the adult neural stem cell lineage. Cell Rep 18:777-790.

Eriksson PS, Perf i lieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson D, Gage FH (1998) Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med 4:1313-1317.

Ernst A, Alkass K, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Perl S, Tisdale J, Possnert G, Druid H, Frisén J (2014) Neurogenesis in the striatum of the adult human brain. Cell 156:1072-1083.

Fiorelli R, Azim K, Fischer B, Raineteau O (2015) Adding a spatial dimension to postnatal ventricular-subventricular zone neurogenesis. Development 142:2109-2120.

Franklin RJM, Gallo V (2014) The translational biology of remyelination: Past, present, and future. Glia 62:1905-1915.

Fünfschilling U, Supplie LM, Mahad D, Boretius S, Saab AS, Edgar J, Brinkmann BG, Kassmann CM, Tzvetanova ID, Möbius W, Diaz F, Meijer D, Suter U, Hamprecht B, Sereda MW, Moraes CT, Frahm J, Goebbels S, Nave KA (2012) Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature 485:517-521.

Gledhill RF, McDonald WI (1977) Morphological characteristics of central demyelination and remyelination: A single-f i ber study. Ann Neurol 1:552-560.

Göttle P, Sabo JK, Heinen A, Venables G, Torres K, Tzekova N, Parras CM, Kremer D, Hartung HP, Cate HS, Küry P (2015) Oligodendroglial maturation is dependent on intracellular protein shuttling. J Neurosci 35:906-919.

Grebbin BM, Hau AC, Groß A, Anders-Maurer M, Schramm J, Koss M, Wille C, Mittelbronn M, Selleri L, Schulte D (2016) Pbx1 is required for adult SVZ neurogenesis. Development 143:2281-2291.

Hack MA, Saghatelyan A, de Chevigny A, Pfeifer A, Ashery-Padan R, Lledo PM, Götz M (2005) Neuronal fate determinants of adult olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 8:865-872.

Hamilton LK, Joppé SE, M Cochard L, Fernandes KJ (2013) Aging and neurogenesis in the adult forebrain: what we have learned and where we should go from here. Eur J Neurosci 37:1978-1986.

Jablonska B, Aguirre A, Raymond M, Szabo G, Kitabatake Y, Sailor KA, Ming GL, Song H, Gallo V (2010) Chordin-induced lineage plasticity of adult SVZ neuroblasts aer demyelination. Nat Neurosci 13:541-550.

Jadasz JJ, Aigner L, Rivera FJ, Küry P (2012a)e remyelination Philosopher’s Stone: Stem and progenitor cell therapies for multiple sclerosis. Cell Tissue Res 349:331-347.

Jadasz JJ, Rivera FJ, Taubert A, Kandasamy M, Sandner B, Weidner N, Aktas O, Hartung HP, Aigner L, Küry P (2012b) P57Kip2 regulates glial fate decision in adult neural stem cells. Development 139:3306-3315.

Jessberger S, Toni N, Clemenson GD, Ray J, Gage FH (2008) Directed differentiation of hippocampal stem/progenitor cells in the adult brain. Nat Neurosci 11:888-893.

Jhaveri DJ, O’Keeffe I, Robinson GJ, Zhao QY, Zhang ZH, Nink V, Narayanan RK, Osborne GW, Wray NR, Bartlett PF (2015) Purification of neural precursor cells reveals the presence of distinct, stimulus-specif i c subpopulations of quiescent precursors in the adult mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci 35:8132-8144.

Karalay O, Doberauer K, Vadodaria KC, Knobloch M, Berti L, Miquelajauregui A, Schwark M, Jagasia R, Taketo MM, Tarabykin V, Lie DC, Jessberger S (2011) Prospero-related homeobox 1 gene (Prox1) is regulated by canonical Wnt signaling and has a stage-specif i c role in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:5807-5812.

Kazanis I, Evans KA, Andreopoulou E, Dimitriou C, Koutsakis C, Karadottir RT, Franklin RJM (2017) Subependymal zone-derived oligodendroblasts respond to focal demyelination but fail to generate myelin in young and aged mice. Stem Cell Rep 8:685-700.

Kornek B, Lassmann H (2003) Neuropathology of multiple sclerosis-new concepts. Brain Res Bull 61:321-326.

Kremer D, Aktas O, Hartung HP, Küry P (2011)e complex world of oligodendroglial differentiation inhibitors. Ann Neurol 69:602-618.

Kremer D, Göttle P, Hartung HP, Küry P (2016) Pushing forward: remyelination as the new frontier in CNS diseases. Trends Neurosci 39:246-263.

Kremer D, Heinen A, Jadasz J, Göttle P, Zimmermann K, Zickler P, Jander S, Hartung HP, Küry P (2009) P57Kip2 is dynamically regulated in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and interferes with oligodendroglial maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:9087-9092.

Kuhlmann T, Miron V, Cui Q, Cuo Q, Wegner C, Antel J, Brück W (2008) differentiation block of oligodendroglial progenitor cells as a cause for remyelination failure in chronic multiple sclerosis. Brain 131:1749-1758.

Kuhn HG, Dickinson-Anson H, Gage FH (1996) Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci 16:2027-2033.

Laywell ED, Rakic P, Kukekov VG, Holland EC, Steindler DA (2000) Identif i cation of a multipotent astrocytic stem cell in the immature and adult mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:13883-13888.

Lee Y, Morrison BM, Li Y, Lengacher S, Farah MH, Hof f man PN, Liu Y, Tsingalia A, Jin L, Zhang PW, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Rothstein JD (2012) Oligodendroglia metabolically support axons and contribute to neurodegeneration. Nature 487:443-448.

Llorens-Bobadilla E, Zhao S, Baser A, Saiz-Castro G, Zwadlo K, Martin-Villalba A (2015) Single-cell transcriptomics reveals a population of dormant neural stem cells that become activated upon brain injury. Cell Stem Cell 17:329-340.

Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A (1993) Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:2074-2077.

Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A (1994) Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science 264:1145-1148.

Maire CL, Wegener A, Kerninon C, Oumesmar BN (2010) Gain-offunction of olig transcription factors enhances oligodendrogenesis and myelination. Stem Cells 28:1611-1622.

Marques S, Zeisel A, Codeluppi S, van Bruggen D, Mendanha Falcão A, Xiao L, Li H, Häring M, Hochgerner H, Romanov RA, Gyllborg D, Muñoz-Manchado AB, La Manno G, Lönnerberg P, Floriddia EM, Rezayee F, Ernfors P, Arenas E, Hjerling-Leffler J, Harkany T, et al. (2016) Oligodendrocyte heterogeneity in the mouse juvenile and adult central nervous system. Science 352:1326-1329.

Mecha M, Feliú A, Carrillo-Salinas FJ, Mestre L, Guaza C (2013) Mobilization of progenitors in the subventricular zone to undergo oligodendrogenesis in theeiler’s virus model of multiple sclerosis: Implications for remyelination at lesions sites. Exp Neurol 250:348-352.

Mechawar N, Savitz J (2016) Neuropathology of mood disorders: do we see the stigmata of inf l ammation? Transl Psychiatry 6:e946.

Meletis K, Barnabé-Heider F, Carlén M, Evergren E, Tomilin N, Shupliakov O, Frisén J (2008) Spinal cord injury reveals multilineage differentiation of ependymal cells. PLoS Biol 6:1494-1507.

Menn B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yaschine C, Gonzalez-Perez O, Rowitch D, Alvarez-Buylla A (2006) Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J Neurosci 26:7907-7918.

Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A (2007) Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science 317:381-384.

Mirzadeh Z, Merkle FT, Soriano-Navarro M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A (2008) Neural stem cells confer unique pinwheel architecture to the ventricular surface in neurogenic regions of the adult brain. Cell Stem Cell 3:265-278.

Moshref i-Ravasdjani B, Dublin P, Seifert G, Jennissen K, Steinhäuser C, Kaf i tz KW, Rose CR (2017) Changes in the proliferative capacity of NG2 cell subpopulations during postnatal development of the mouse hippocampus. Brain Struct Funct 222:831-847.

Nait-Oumesmar B, Decker L, Lachapelle F, Avellana-Adalid V, Bachelin C, Baron-Van Evercooren A (1999) Progenitor cells of the adult mouse subventricular zone proliferate, migrate and differentiate into oligodendrocytes aer demyelination. Eur J Neurosci 11:4357-4366.

Nait-Oumesmar B, Picard-Riera N, Kerninon C, Decker L, Seilhean D, Höglinger GU, Hirsch EC, Reynolds R, Baron-Van Evercooren A (2007) Activation of the subventricular zone in multiple sclerosis: evidence for early glial progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:4694-4699.

Nakatani H, Martin E, Hassani H, Clavairoly A, Maire CL, Viadieu A, Kerninon C, Delmasure A, Frah M, Weber M, Nakafuku M, Zalc B,omas JL, Guillemot F, Nait-Oumesmar B, Parras C (2013) Ascl1/ Mash1 promotes brain oligodendrogenesis during myelination and remyelination. J Neurosci 33:9752-9768.

Oishi S, Zalucki O, Premarathne S, Wood SA, Piper M (2016) USP9X deletion elevates the density of oligodendrocytes within the postnatal dentate gyrus. Neurogenesis 3:e1235524.

Ortega F, Gascón S, Masserdotti G, Deshpande A, Simon C, Fischer J, Dimou L, Chichung Lie D, Schroeder T, Berninger B (2013) Oligodendrogliogenic and neurogenic adult subependymal zone neural stem cells constitute distinct lineages and exhibit differential responsiveness to Wnt signalling. Nat Cell Biol 15:602-613.

Patani R, Balaratnam M, Vora A, Reynolds R (2007) Remyelination can be extensive in multiple sclerosis despite a long disease course. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 33:277-287.

Patrikios P, Stadelmann C, Kutzelnigg A, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M, Laursen H, Sorensen PS, Bruck W, Lucchinetti C, Lassmann H (2006) Remyelination is extensive in a subset of multiple sclerosis patients. Brain 129:3165-3172.

Perlman SJ, Mar S (2012) Leukodystrophies. In: Advances in experimental medicine and biology, pp154-171.

Piaton G, Williams A, Seilhean D, Lubetzki C (2009) Remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Prog Brain Res 175:453-464.

Picard-Riera N, Decker L, Delarasse C, Goude K, Nait-Oumesmar B, Liblau R, Pham-Dinh D, Baron-Van Evercooren A (2002) Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mobilizes neural progenitors from the subventricular zone to undergo oligodendrogenesis in adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:13211-13216.

Rafalski VA, Ho PP, Brett JO, Ucar D, Dugas JC, Pollina EA, Chow LML, Ibrahim A, Baker SJ, Barres BA, Steinman L, Brunet A (2013) Expansion of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells following SIRT1 inactivation in the adult brain. Nat Cell Biol 15:614-624.

Rivera FJ, Couillard-Despres S, Pedre X, Ploetz S, Caioni M, Lois C, Bogdahn U, Aigner L (2006) Mesenchymal stem cells instruct oligodendrogenic fate decision on adult neural stem cells. Stem Cells 24:2209-2219.

Rivera FJ, Stef f enhagen C, Kremer D, Kandasamy M, Sandner B, Couillard-Despres S, Weidner N, Küry P, Aigner L (2010) Deciphering the oligodendrogenic program of neural progenitors: cell intrinsic and extrinsic regulators. Stem Cells Dev 19:595-606.

Rolando C, Erni A, Grison A, Beattie R, Engler A, Gokhale PJ, Milo M, Wegleiter T, Jessberger S, Taylor V (2016) Multipotency of adult hippocampal NSCs in vivo is restricted by Drosha/NFIB. Cell Stem Cell 19:653-662.

Scolding N, Franklin R, Stevens S, Heldin CH, Compston A, Newcombe J (1998) Oligodendrocyte progenitors are present in the normal adult human CNS and in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. Brain 121:2221-2228.

Seri B, García-Verdugo JM, Collado-Morente L, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A (2004) Cell types, lineage, and architecture of the germinal zone in the adult dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol 478:359-378.

Seri B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A (2001) Astrocytes give rise to new neurons in the adult mammalian hippocampus. J Neurosci 21:7153-7160.

Seri B, Herrera DG, Gritti A, Ferron S, Collado L, Vescovi A, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A (2006) Composition and organization of the SCZ: a large germinal layer containing neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cereb Cortex 16 Suppl 1:i103-i111.

Shihabuddin LS, Horner PJ, Ray J, Gage FH (2000) Adult spinal cord stem cells generate neurons aer transplantation in the adult dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 20:8727-8735.

Shin J, Berg DA, Zhu Y, Shin JY, Song J, Bonaguidi MA, Enikolopov G, Nauen DW, Christian KM, Ming GL, Song H (2015) Single-cell RNA-seq with waterfall reveals molecular cascades underlying adult neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 17:360-372.

Stef f enhagen C, Dechant FX, Oberbauer E, Furtner T, Weidner N, Küry P, Aigner L, Rivera FJ (2012) Mesenchymal stem cells prime proliferating adult neural progenitors toward an oligodendrocyte fate. Stem Cells Dev 21:1838-1851.

Suhonen JO, Peterson DA, Ray J, Gage FH (1996) Differentiation of adult hippocampus-derived progenitors into olfactory neurons in vivo. Nature 383:624-627.

Sun GJ, Zhou Y, Ito S, Bonaguidi MA, Stein-O’Brien G, Kawasaki NK, Modak N, Zhu Y, Ming GL, Song H (2015) Latent tri-lineage potential of adult hippocampal neural stem cells revealed by Nf1 inactivation. Nat Neurosci 18:1722-1724.

van Wijngaarden P, Franklin RJM (2013) Ageing stem and progenitor cells: implications for rejuvenation of the central nervous system. Development 140:2562-2575.

Weickert CS, Webster MJ, Colvin SM, Herman MM, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE (2000) Localization of epidermal growth factor receptors and putative neuroblasts in human subependymal zone. J Comp Neurol 423:359-372.

Weissleder C, Fung SJ, Wong MW, Barry G, Double KL, Halliday GM, Webster MJ, Weickert CS (2016) Decline in proliferation and immature neuron markers in the human subependymal zone during aging: relationship to EGF- and FGF-related transcripts. Front Aging Neurosci 8:274.

Wolswijk G (1998) Chronic stage multiple sclerosis lesions contain a relatively quiescent population of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. J Neurosci 18:601-609.

Xing YL, Röth PT, Stratton JAS, Chuang BHA, Danne J, Ellis SL, Ng SW, Kilpatrick TJ, Merson TD (2014) Adult neural precursor cells from the subventricular zone contribute signif i cantly to oligodendrocyte regeneration and remyelination. J Neurosci 34:14128-14146.

Young KM, Merson TD, Sotthibundhu A, Coulson EJ, Bartlett PF (2007) p75 neurotrophin receptor expression def i nes a population of BDNF-responsive neurogenic precursor cells. J Neurosci 27:5146-5155.

*< class="emphasis_italic">Correspondence to: Patrick Küry, Ph.D., kuery@uni-duesseldorf.de.

Patrick Küry, Ph.D., kuery@uni-duesseldorf.de.

orcid: 0000-0003-1583-9987 (Rainer Akkermann) 0000-0002-3329-0249 (Felix Beyer) 0000-0002-2654-1126 (Patrick Küry)

10.4103/1673-5374.204999

Accepted: 2017-04-10

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- The reasons for end-to-side coaptation: how does lateral axon sprouting work?

- Endothelial progenitor cells as a therapeutic option in intracerebral hemorrhage

- Phosphatidylserine improves axonal transport by inhibition of HDAC and has potential in treatment of neurodegenerative diseases

- RhoA as a target to promote neuronal survival and axon regeneration

- Recovery of multiply injured ascending reticular activating systems in a stroke patient

- The complexities underlying age-related macular degeneration: could amyloid beta play an important role?