Food, polyphenols and neuroprotection

2017-05-03RuiF.M.Silva,LeaPoganik

Food, polyphenols and neuroprotection

Neuron loss and neurodegeneration are the common denominators of what are known as neurodegenerative diseases. Although the clinical manifestations of some neurodegenerative diseases are mainly associated with ageing, it is believed that onset of disease and neuronal death occurs progressively through life, well before the fi rst symptoms appear. So, one of the main dilemmas regarding neurodegenerative disease therapies is that treatment often starts long after the neurodegeneration has occurred, when a great number of neurons have already been lost. Furthermore, little information is a available about how to keep the brain healthy, and there is a great need for novel risk-reduction approaches. Consequently, new strategies to prevent and/or to overcome neurodegeneration that will increase the long-term health of the brain, or reduce the risk of neurodegeneration, will have great impact not only socially but also economically. Of note, in spite of their specif i c pathways, many neurodegenerative conditions share common mechanisms, such as neuroinf l ammation and oxidative stress. Indeed, the possible role of reduced expression or imbalance of oxidative stress regulatory genes in ageing and neurodegeneration, and the possible protection by antioxidants, has oen been discussed.e concept that diet can have a crucial role as one of those strategies, to contribute to healthy ageing, has been indicated more recently, which gave rise to the concept of nutraceuticals. A possible solution to this dilemma might therefore be to naturally increase the intrinsic brain defences, and to avoid, or at least reduce, the initial insults that lead to neurodegenerative processes. To this end, several studies have focused on the importance of nutritional consumption of natural products, as food itself or as food supplements that can convey neuroprotection.

One of the first indications of biological activities from food-derived compounds was the discovery of the antibacterial properties of curcumin, which was published inNaturein the late 1940’s by Schraufstatter and Bernt. Other food polyphenols, and particularly resveratrol, have also attracted attention, as suggested by the possible association between red wine consumption in France and low incidence of coronary heart diseases.is association might be explained by the antioxidative properties of food polyphenols, in this case resveratrol, which have also been shown to convey neuroprotective activities to such compounds (Granzotto and Zatta, 2014).

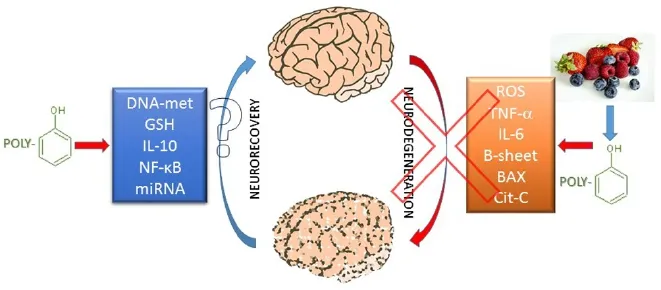

Figure 1 Possible pathways of food polyphenol interventions in neurodegeneration.

Recently, it has become increasingly evident that food-born phenolic compounds (e.g., phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenes) can modulate several cell functions, processes that go well beyond their first-described natural antioxidant capacities. Vegetables, fruit, nuts, chocolate and other types of foods and beverages, such as wine, cof f ee and tea, are all rich sources of polyphenols. It was recently shown that curcumin from turmeric has not only strong antioxidant activity, but also anti-inf l ammatory properties, with reduction of astrocyte production of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 (and reactive oxygen species) in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Curcumin modulates both myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)-dependent and TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-dependent pathways in tolllike receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling (Yu et al., 2016). Also, an anti-amyloid capacity for epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) has already been described, which can act as a ‘b-sheet breaker’, and so shows neuroprotective characteristics that go far beyond its antioxidative properties, even if central nervous system (CNS) access remains to be fully established (Boyanapalli and Tony Kong, 2015). Recently, it was also demonstrated that signif i cant levels of EGCG can cross a human blood-brain barrier model and protect cortical cultured neurons from oxidative-stress-induced cell death (Pogacnik et al., 2016). Further molecular mechanisms of EGCG activity include inhibition of Bax, cytochrome c translocation, and autophagic pathways, through increasing LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (LC3-II) (Lee et al., 2015), and modulation of mitochondrial functions, as reviewed by Oliveira et al. (2016). However, recent studies have also raised some concerns about eventual toxicity problems of high brain concentrations of some antioxidants, such as quercetin (Pogacnik et al., 2016), which as well as its benef i cial properties towards neurons, has shown toxicity towards different cultured cells. Hence, the possible toxicity problem also has to be considered in clinical trials designed for the use ofpolyphenols in dementia (Molino et al., 2016). However, polyphenols can undergo several chemical transformations after being consumed orally (i.e., deglycosylation, dehydroxylation, demethylation, oxidation), and their bioavailability depends not only on the molecule itself, but also on each individual (Lewandowska et al., 2013). However, it is conceivable that due to the relatively low bioavailability of dietary polyphenols (see Pandareesh et al., 2015, for a list of the bioavailability of dietary polyphenols in the CNS), high and potentially toxic concentrations can only be reached if the polyphenols are used as either concentrated supplements or therapeutic medicines. Considering the clinical course of most of the neurodegenerative diseases, it appears that the greatest valuable use of polyphenols might be their dietary enrichment through life, assuming that their regular consumption can increase, or contribute to an increase of, the brain defences against senescence and neurodegeneration (Figure 1). Indeed, a growing field of research illustrates the possibility for epigenetic modulation by dietary consumption of polyphenols, namely for the modulation of pro-inf l ammatory and anti-inf l ammatory microRNAs (Tili and Michaille, 2016), as well as DNA and histone methylation (Boyanapalli and Tony Kong, 2015). Examples of these properties can be seen in the described neuroprotectionviaautophagy modulation in a prion disease model (Lee et al., 2015). A recent review highlighted the epigenetic modulation of curcumin (Boyanapalli and Tony Kong, 2015), which includes inhibition of DNA methyltransferases, regulation of histone modif i cations through regulation of histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs), and regulation of microRNAs. It is also worth mentioning that the described modulation of endothelial cell inf l ammation through epigenetic regulation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) target genes by EGCG that was proposed by Liu et al. (2016) as a benef i cial agent against the vascular toxicity of environmental pollutants, might also have an important impact on the protection of blood-brain barrier function in neurodegenerative diseases.

Interestingly, a recent retrospective cohort study on the prevalence of dementia in the U.S. showed a significant decrease in incidence of dementia cases between 2000 and 2012 (Langa et al., 2016). Although the underlying reasons that led to this decrease remain unexplained, the authors tentatively attributed it to increases in the levels of education and/or treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in the most recent population. As such, it can also be speculated that the growing awareness of the population regarding healthy food and nutrition that has led to the introduction of increasing amounts of fruits and vegetables into the daily diet has contributed to this decreased incidence of dementia.

In conclusion, food polyphenols appear to be a promising therapeutic approach to slow down the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. However, we believe that their biggest potential might very well arise from their promotion of the brain natural defences through their regular consumption in the diet. As such, natural food polyphenols would act more as prophylactic rather than therapeutic compounds. Although more dif ficult to demonstrate, because of the need for longer animal and population studies, this possibility deserves to be validated by further studies, due to the possible large ef f ects it might have on the well-being of society and its great socioeconomic impact.

Rui F.M. Silva, Lea Pogačnik*

Research Institute for Medicines (iMed.ULisboa) and Department of Biochemistry and Human Biology (DBBH), Faculty of Pharmacy, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal (Silva RFM) Department of Food Science and Technology, Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia (Pogačnik L)

*Correspondence to:Lea Pogačnik, Ph.D., lea.pogacnik@bf.uni-lj.si.

Accepted:2017-03-28

orcid:0000-0003-1008-0633 (Lea Pogačnik)

Boyanapalli SS, Tony Kong AN (2015) “Curcumin, the King of Spices”: epigenetic regulatory mechanisms in the prevention of cancer, neurological, and inf l ammatory diseases. Curr Pharmacol Rep 1:129-139.

Granzotto A, Zatta P (2014) Resveratrol and Alzheimer’s disease: message in a bottle on red wine and cognition. Front Aging Neurosci 6:95.

Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, Faul JD, Levine DA, Kabeto MU, Weir DR (2016) A comparison of the prevalence of dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med 177(1):51-58.

Lee JH, Moon JH, Kim SW, Jeong JK, Nazim UM, Lee YJ, Seol JW, Park SY (2015) EGCG-mediated autophagy fl ux has a neuroprotection ef f ect via a class III histone deacetylase in primary neuron cells. Oncotarget 6:9701-9717.

Lewandowska U, Szewczyk K, Hrabec E, Janecka A, Gorlach S (2013) Overview of metabolism and bioavailability enhancement of polyphenols. J Agricult Food Chem 61:12183-12199.

Liu D, Perkins JT, Hennig B (2016) EGCG prevents PCB-126-induced endothelial cell inf l ammation via epigenetic modif i cations of NF-kappaB target genes in human endothelial cells. J Nutr Biochem 28:164-170.

Molino S, Dossena M, Buonocore D, Ferrari F, Venturini L, Ricevuti G, Verri M (2016) Polyphenols in dementia: from molecular basis to clinical trials. Life Sci 161:69-77.

Oliveira MR, Nabavi SF, Daglia M, Rastrelli L, Nabavi SM (2016) Epigallocatechin gallate and mitochondria- astory of life and death. Pharmacol Res 104:70-85.

Pandareesh MD, Mythri RB, Srinivas Bharath MM (2015) Bioavailability of dietary polyphenols: factors contributing to their clinical application in CNS diseases. Neurochem Int 89:198-208.

Pogacnik L, Pirc K, Palmela I, Skrt M, Kim KS, Brites D, Brito MA, Ulrih NP, Silva RF (2016) Potential for brain accessibility and analysis of stability of selected flavonoids in relation to neuroprotection in vitro. Brain Res 1651:17-26.

Tili E, Michaille JJ (2016) Promiscuous effects of some phenolic natural products on inf l ammation at least in part arise from their ability to modulate the expression of global regulators, namely microRNAs. Molecules 21:E1263.

Yu S, Wang X, He X, Wang Y, Gao S, Ren L, Shi Y (2016) Curcumin exerts anti-inf l ammatory and antioxidative properties in 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion (MPP(+))-stimulated mesencephalic astrocytes by interference with TLR4 and downstream signaling pathway. Cell Stress Chaperones 21:697-705.

10.4103/1673-5374.205096

How to cite this article:Silva RFM, Pogačnik L (2017) Food, polyphenols and neuroprotection. Neural Regen Res 12(4):582-583.

Open access statement:This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Recovery of multiply injured ascending reticular activating systems in a stroke patient

- Neuroprotective mechanism of Kai Xin San: upregulation of hippocampal insulin-degrading enzyme protein expression and acceleration of amyloid-beta degradation

- Mitomycin C induces apoptosis in human epidural scar fi broblasts after surgical decompression for spinal cord injury

- Exenatide promotes regeneration of injured rat sciatic nerve

- Recombinant human fi broblast growth factor-2 promotes nerve regeneration and functional recovery after mental nerve crush injury

- Ca2+involvement in activation of extracellular-signalregulated-kinase 1/2 and m-calpain after axotomy of the sciatic nerve