Originality, Authenticity, and Humor:The Charms of Trisha Brown’s Dance

2017-04-09USSusanRosenbergWUJunyi

[US] Susan Rosenberg/WU Jun-yi

The message author of the International Dance Day 2017 is the great dancer, artist, and educator Trisha Brown. However, it is with great sadness that she passed away on March 18th, 2017, after a lengthy illness. On April 28th, the reporter WU Jun-yi (hereafter referred to as W)interviewed the Consulting Historical Scholar of the Trisha Brown Dance Company Susan Rosenberg(hereafter referred to as S), who was also invited as a speaker of the keynote speech for the International Dance Day, on the artistic career, artistic spirit, and artistic charms of this message author.

W: We know that Trisha Brown is the message author of the International Dance Day 2017. Can you tell us what amessage author is?

S: The message author speaks to the theme of the conference, which this year is “We Dance, Together,”and the message author’s goal is to communicate internationally about the importance of dance as an art form and to promote their particular vision of dance,which in Trisha’s case comes from her background of a fifty year career in the field.

W: Indeed, in terms of the contribution that she has made to the dance field and the artistic significance of her works, it is undisputed that she shall be this year’s massage author. Can you please give us a briefintro of Trisha Brown?

S: Well, Trisha started as part of an experimental group working in both California and New York. She got her beginnings in the 1960s—she was one of the first people to settle in SOHO, Low Manhattan, New York,in the “lof t district” there. She started her company in 1970 and had a very unconventional beginning, working outside of theatres, making dances where people walked down the sides of buildings, or did performances on streets or on roof tops. She began a very conceptual investigation into what dance movement could be, basically stripping down dance from all technical virtuosity and to say that just walking is dance, or everyday movement can be dance. Then she invented her own abstract movement forms, of ten working with very conceptual scores and notations. In 1978, she began to invent her own new movement language, based on her extraordinary abilities as a dancer. And then she began working on the stage for the first time collaborating with America’s greatest visual artists and teaching other dancers the movement language that she discovered in her own body.

W: Apparently, Trisha’s dance comes from outside the box. Now, I know that she was good at math as a youngster. Do you think she applied some of her math learning to her dance?

S: Um...I didn’t know that she had a talent for mathematics in her youth. Actually, that is new information to me! There was only a very briefperiod in her career when she used mathematics as a structural principle in her dances, and it came at a time when other artists, sculptors in particular, were using mathematics as a structural principle in their work. So it was really only between 1971 and 1975 that she used mathematics. She never created dance tomusic, so her dancers do not count,which is very unusual in dance. Usually, dancers count to the timing of the music, but for the first two decades of her career, she largely performed in silence. So there was no musical counting whatsoever, although it could be said mathematics played a part in how she structured her compositions.

W: Let’s talk about Trisha Brown’s dance life.When did Trisha start to dance? Did she have any academic dance training before she started to do modern dance?

S: Well, Trisha never really studied ballet. She studied all of the major modern techniques of the time. As a young girl, she studied tap and jazz, because she grew up in a very small town in the Pacific North West of the United States. I don’t think that Trisha’s dance reflects any formal training, because she invented her own way of moving completely. She had a very, very special body in terms of its flexibility and its spontaneity. The connection between her mind and her body was so deep that she invented something completely original. So, it is very difficult to make connections with anything that came before her—she was so unique.

W: Did she ever try gymnastics since we can see a lot of related elements in her dance?

S: No, not at all. She grew up in the Pacific North West near the rainforest on the Olympic Peninsula, and she was very much an outdoors person as a child—she climbed trees; she ran in the water; she went fishing and hunting with her father. She loved nature, and she said,“The rainforest was my art school.” So she learned from nature, playing outdoors about her body and athleticism.Also, her brother was a star athlete in [American]Football and in basketball. And they played together—even though she was a girl, he would play [American]Football together, and he even tried to train her on how to do the Pole-Vault! So she was extremely athletic, but she never did gymnastics. The closest she came was that she traveled to India in 1970. She did witness Indian circus performers doing very high-climbing balancing acts. And she was very interested in this, but she never took any formal training in gymnastics or the circus arts.

W: It seems that the nature has a big influence on her. In the 1970s, Trisha incorporated a lot of movements from people’s daily and normal lives into her dances, and even the dance venues she selected were natural environments and open spaces. Do you think this is influenced by the popularity of oriental Zen at that time among artists and intellectuals?

S: That’s an interesting question. I don’t know about any Asian influence on her dance, but what comes to mind most of all was that the composer John Cage was a very, very strong influence on Trisha Brown. John Cage was one of the most important people in the United States to bring Asian philosophies to music and dance.I also know that it is probable that Trisha’s dancers did exercises such asTai Chi, and that they would looked for techniques of non-western movement in their investigations of the body and improvisation.

W: Some scholar divided Trisha’s dance life into four stages: structure improvisation, installation,accumulation, and release. In the first stage of structure improvisation, Trisha took part in the Judson Dance Theater. Can you tell us something about this Judson Dance Theater?

S: The Judson Dance Theater is actually the result of a class on choreographic composition, which was taught by a man named Robert Dunne who was a student of John Cage, the composer. The class was supposed to teach choreographers and dancers John Cage’s ideas on musical composition. Out of that class came a series of recitals which took place at Judson Church, which is downtown [New York] on the south side of a park called Washington Square Park. Trisha participated in Judson Dance Theater—it was a collective of people that were sharing new ideas for how to “make up a way of how to make up a dance,” which was a quote from Trisha. How do you “make up a way to make up a dance” when you have gotten rid of all the existing ways of composing?So it was a place where all these new dances were shown. Trisha took part as a performer in many of her colleagues works—they all performed in each other’s works. She was very young in her career then. She made several works that were performed at Judson Church as well, as that was the place where the question “What is dance?” was asked— “what can be dance? what does dance encompass?” , and also the act of getting rid of the conventional notions of what dance was; that is what the Judson Dance Centre did essentially.

W: We may consider Judson Dance Theater as the HQ for the American experimental dance.Did Trisha’s more experimental dances receive any negative reviews or even boycotts when she was at the Judson Dance Theater?

S: Yes, actually, there is a famous story that while I was writing my book I discovered, no-one knew about until now, which is that most of the people in Judson just performed at the church in front of their family and friends. So the New York press would write a review and ask, “what’s going on here?” or whatever. Since most of the audiences were friends, so it was very well received.Trisha, very differently from everyone else in Judson,wanted to show her dance at the Modern Dance Festival,which at that time took place in New London, Connecticut.So she took a dance, her first one, made in New York,in this very experimental context, to New London and auditioned it for performance in this place where everyone was dancing—Martha Graham, Eric Hawkins,and Merce Cunningham, and Doris Humphrey—and all the great modern dance techniques were taught there. I discovered in my research that it created this huge conflict. They rejected the dance, and then the students rose up and said, “no, no you have to include it!” —they thought it was brilliant. It caused a big fight at the center of modern dance in America at that time. So Trisha fought and fought and they said “Okay, you can do the dance but have to lose the soundtrack,” because the soundtrack was a vacuum cleaner and a woman’s voice. Trisha said,“no, I refuse to do it unless it has the sound.” And then she did it. Then, she wrote about it—I discovered in the letters she wrote and that other people wrote who were there at the time. It was the first time ever that there was a conflict at the American Dance Festival. I am sure she did it deliberately to find out how her new work would be perceived by people in the modern dance field, because she didn’t know. Everyone in New York was clapping and excited, but she took it to a new context and everyone found it surprising and shocking.

W: Trisha’s experiments even made the simple“walking” more meaningful. “Walking on the Wall”is a work which was so different at its time in term of performing, props, venue, and even the way for audiences to watch. Can you tell us something about this work?

S: Well, the first version was called “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building,” and that was done in 1970 on a seven-story building where Trisha lived in Soho. A man was positioned at the top and held by rope. He had to put his body perpendicular to the ground and then walk done the side of a building. This was an experiment using gravity, and it was an experiment of walking against the natural course of gravity—for ifhe had followed gravity,his body would of collapsed. So he had to pantomime and tried to look like he was walking naturally. This didn’t really just show dance to be walking—or walking to be dance—it showed the idea that we are filled with physical memories that we don’t think about. Ifyou are put in a position where you are asked to walk vertically, you have to ask yourself“what does my body do when I walk?what is walking made of ?”

That was the first experiment. Then she was invited to the Whitney Museum, and she did the walking on the walls, horizontally walking on the walls, instead of vertically walking down the walls. And that was a group piece for 7 dancers. It was a very important event—it occurred in one of America’s most famous museums, a rare time where dance was shown in a museum, which is very important to today, as now dance is shown all over in museums everywhere. That was an experiment which did not have a beginning, a middle, and an end,as when you walked vertically as this told you when to stop, and thus allowed her to reorient the perception of walking. The audience said it felt as though they were looking down on the performers, because their heads were sticking out the wall as they walked around the wall. These are some of her earliest, radical, and most dangerous—very dangerous—experiments, with testing the limits of the body and the body’s memory of what its most everyday behavior is.

W: After this, Trisha entered a period in her career,which we may call as accumulation stage, when she created most of her widely known modern dance techniques...

S: Yes, it was very much a signature dance of hers, as the dances just mentioned—the “equipment dances” like “Walking on the Wall” —saw Trisha using architectural equipment as the score for her dance. She didn’t have to make too many decisions; she just had to set it up, and then it would happen, you know, setup the harnesses and the ropes and walk. She was not that interested in the fact that in making up a dance a choreographer has to make up so many complex decisions, decisions which come subjectively—out of the self. Trisha wanted to find a more objective system for working. Mathematics gave her a system, and that system is accumulation, which is 1, 1+2, 1+2+3, 1+2+3+4, ...It goes back to the beginning and restarts the dance. She made about 17 different dances that used accumulating,or de-accumulating, in a variety of patterns. Because the first one was a solo, it became what I call a signature,in that the fact that she repurposed the system but used different movement forms. In some cases, the performers were lying on the floor accumulating. The movement principle, that is the choreographic composition, was mathematical. But the movement principle was based on the fact the body has three anatomical principles according to Trisha Brown: bend, stretch, and rotate. All of the accumulation dances use this similar anatomical structure, which explores the different ways in which the body can bend, stretch, and rotate, and the different movement forms that come out of exploring those possibilities. of course, the secret, mystery, and beauty of the dance is that we really don’t know what Trisha decided on which forms, except that they are very, very beautiful and very, very unusual. Even though she said she was not making subjective decisions, because the body just bends, stretches, and rotates, and she used numbers to compose, of course she made many subjective decisions about the forms she used, and the forms were of most interest to her, were the most mysterious thing, and are what I think make the dances so beautiful.

W: Trisha even made the traditional dance different. What about her work “Spanish Dance,”which was different from the Flamenco we expect?

S: As you know, the dance involves 5 dancers placed in a row, and they have to be placed between two walls,which is the most important part of the dance. As in “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building,” Trisha is dividing up time and space between two walls. The dance is set to a song of the great American folksinger Bob Dylan,but sung by a different artist Gordon Lightfoot, calledEarly Morning Rain. The dancers just shuffle up, rotating their hips slightly, until one dancer picks up another, and another, and then while they are doing this—I cannot show you as I am not a dancer—they raise their arms above their heads with great flourish, as ifthey were doing a Spanish type of dance on the upper part of the body, while the lower part of the body is just wiggling. The Spanish part[of the dance] is very proud, very dramatic, but when they come to the wall [Susan makes clapping sound], they pile up and hit the wall—it is very funny! It ismeantto be a very funny dance, and it is supposed to respect the drama which certain dances, like Flamenco or Spanish dance, have and say “wow, look at this extravagant form”whilst at the same time doing it in a minimalist way and making a joke about the fact that she is using architecture to structure the time and space of the dance. So I think it is Trisha being funny. It is one of her most popular dances, one of her most performed dances, for a number of reasons. One is that it requires a certain musicality, as obviously keeping rhythm with bodies is very difficult.But it does not require jumping and twirling, and so people of all ages can do it and learn that dance.

W: Trisha once suggested she saw herselfas a “humorous” dancer. Where do you think this came from?

S: Yes, Trisha was a person of great humor, wit, and playfulness. Inevitably, who an artist is becomes a part of their work. Trisha loved puns, and a lot of her dances are very funny. Ifyou look at the details, in that dance for example [the above mentioned “Spanish Dance”],the dancers are doing these movements and then [claps]boom!—they crash into a wall and it is all over. In some of her other dances, she would play games, like she would tell her dancers “go invisible” —that was one of her instructions—how do you go invisible when you are on the stage? So what they would all do was to lie down on the ground as ifyou couldn’t see them and cover their eyes. Or sometimes, Trisha would make a movement that would involve two people. For example, in “Set and Reset,” she made a movement where someone puts their arms like this [demonstrates the movement] and the other person dives through their arms. And then later on the dance, the performer repeats the hand gesture, but no one dives through. Ifyou’ve seen it before, you know she is making a joke about a previous movement. I am trying to think of other examples—she would just give her dancers instructions which werevery funny. She would say “go here, do this, do this, do this, do this, act like a sexy woman, walk and then be Charlie Chaplin, and then...” She did it to inspire ideas for movement. It was part of her experimental process. In the end, these funny movements would end up in the dance with nicknames which the dancers gave the work. But Trisha could also be extremely serious. Like when she was composing to the work of Johannes Sebastian Bach, she was very serious. But when she composed her first operaL’Orfeo,she told me that sometimes in her mind, in order to get away from normal way of how opera in America or Europe would be produced, she would imagine her characters as cartoon characters, and she would have them doing very exaggerated things—things that we would not necessarily know she was doing, but that in her mind she was always coming up with funny ways to get her dancers to do what she wanted.

W: I heard that she would give some “missions impossible” to her dancers during training. Was that true?

S: That is a great line. I don’t know where you got “Mission Impossible” ! But yes, from the very beginning in the 1960s, when they were doing structured improvisation, there was always the idea that you would give yourselfan impossible instruction and then see what happened. This all part of the idea—how do you give yourselfor make something new? How can you possibly make something new ifyou start with a preconceived idea? Ifyou start by telling yourselfto do something that is completely impossible, like to line up all the parts of your body on top of one another in five minutes or five seconds, then your body has to come up with an answer to the question. This was something Trisha loved to do:think about what would be an impossible instruction that she could think about and tell her dancers. And then whatever comes out of it is completely new. Also sometimes she would have ideas that were impossible,or seemingly impossible. Her dancers would actually do them because she could trick them into situations [where it became possible]. One of the things she would like to do is to say have one dancer here and one here, have them run directly at each other, and see what happens. And so,the body solves problems before the mind even knows they exist. I think of that for when she was making her dance called “Water Motor” in 1978. I can’t remember the exact instructions she gave herself, but she would verbally give herselfan impossible instruction in order to achieve eccentric results; for ifthere is no real answer,then you come up with an imaginary answer. So, yeah,she used that a lot. Also because she made a lot of the movement on her own body and taught it to her dancers,she was of ten using the idea of “Mission Impossible” and making it possible.

W: Trisha’s choreography is well connected with visual arts, for example, dancing on paper while painting the paper with her feet. Is this still dance,or rather, is there a clearly defined barrier between dance and other visual art forms?

S: Is it still dance? That is a very interesting question.In relation to the drawings [dancing on paper whilst painting it with her feet] was a project I worked on with Trisha. That was how I met Trisha—through working on that project with her. She called it “It’s a Draw.” That is another example of her humor, because in English“it’s a draw” means “it’s a tie.” She was saying, “It’s a tie between dance and drawing,” as in neither one is the winner. They are equal in competition with one another. One cannot beat the other. I think that title captures of brilliantly funny and sophisticated her mind was because she was making these drawings by dancing with charcoal between her fingers and toes and an oil stick. The first time she did this she really performed and improvisational dance: she went down on the ground and she stood up. I saw her tap dance with charcoal between her toes, making marks on the ground, and it ended up making a beautiful composition, which because she was composing with her body in space. of course, when she put the marks on the paper on the ground, we see there is really no difference between a gesture made in space and a gesture made on the page, or a gesture in the air or a gesture on the stage. So I think she was playing with the idea that there is no division between these things. All are signs of gesture—or traces of gesture—whether that gesture is made in the air or that gesture is recorded.

W: We know that Trisha and the well-known visual artist Robert Rauschenberg were close friends. Tell us something about the relationship between Trisha and Rauschenberg.

S: Well, Trisha first met Robert Rauschenberg shortly after she arrived in New York. She told me, and she has told many people, that she was a Work-Study Student at the Merce Cunningham Dance Company,where her job was to answer the telephone. And this man named Robert Rauschenberg would call, because Robert Rauschenberg was at the time the Artistic Director of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, and was himselfvery close to Merce Cunningham and John Cage. So Trisha would have these hilarious conversations with him on the phone. Yet she had no idea who he was. One day, she said, “Who is this Robert Rauschenberg?”,because they had already established this rapport. It turns out that she found out when she went to see a famous retrospective of his work in 1963, at the Jewish Museum. It was the first big showing of his work, and she realized, “oh my gosh!” This Robert Rauschenberg is really a major American artist, who was still establishing his career at that time, it should be said. They remained friends. Robert Rauschenberg became involved in dance in the mid-1960s. He would sometimes create dances,or perform in other people’s work. When Trisha began to perform on the theatrical stage in 1979, the first person she said she thought of to work with was Robert Rauschenberg. He had already had a long career working with Merce Cunningham, but was no longer working with the Cunningham Dance Company. They had developed this friendship—it is one of those things where I do not think I could possibly describe. They had a very, very special relationship with one another, partly based on humor and partly based on the fact, which she once told me, that she came from the Pacific North West and at Thanksgiving her family would send her frozen Salmon,and his family came from Texas and they would send him frozen Turkey—or something like that, I don’t know—so they had some American Connection. Then she went on to work with Rauschenberg on five different productions where he created the sets and costumes, beginning with her first work “Glacial Decoy” in 1979, and then,continuing with the work that is going to be performed tomorrow night here in Shanghai “IfYou Couldn’t See Me,” which was Rauschenberg’s idea for Trisha Brown.It is the simplest collaboration they worked on. Their earlier collaborations involved photography and film and lighting, and he made costumes that involved silk screens.He was really the stage designer for four different productions. For the dance being performed in Shanghai,their last collaboration, he gave Trisha Brown the idea to perform with her back to the audience, or should I sayrule—he gave her the rule that she had to make a dance with her back facing the audience, which she was taken aback by “won’t they think I am rude ifI turn my back to them?” He also created the music and the beautiful costume for her.

W: We know that this year’s International Dance Day Message by Trisha Brown was put together by you. As a close friend of Trisha Brown, in your opinion, who is Trisha Brownin conclusion?

S: What kind of person was Trisha? One of the most extraordinary, ifnotthemost extraordinary, persons I have ever met. Trisha was absolutely brilliant. In some people, there is a separation; they can have a brilliant mind or be a brilliant mover, but Trisha was brilliant in her mindandbrilliant in her body. And part of the thing about her humor that was so unusual was because it was her mind and body completely connected to one another.So she could speak with her body like no other. She was incredibly human, incredibly humble for someone of such incredible greatness and brilliance with a contribution to the history of the arts. Her art embodies this idea that“when I’m on the stage, I am a human being, and you can feel my humanity. You can see me breathing. You can see me looking at you. I’m a real person.” That is what she was on the stage and that is what she was in real life. She was extraordinarily caring about her dancers—their welfare and well being in the world. As her message says, which comes from many previous instances where Trisha made her comments about the arts, it shows the importance of the arts to humanity, which she believed in deeply. She understood that dance, as a non-verbal art form, had a special role to play in connecting people of different cultures and societies. And that is part of the message that will be delivered from previous messages that Trisha has delivered.

W: Thank you for this interview, which makes us closer to this dance master Trisha Brown and her works.

(Tom Johnson and CHEN Zhong-wen noted down the text based on the record. Editor: SUN Xiao-yi)

2017年被选为国际舞蹈日献词人的是杰出的舞蹈艺术家、教育家崔莎· 布朗。然而不幸的是,2017年3月18日,崔莎· 布朗因病去世。为了深入了解这位献词人的艺术生涯、艺术精神及其艺术魅力,记者邬钧宜(以下简称W)于4月28日专访了应邀前来参加国际舞蹈日舞蹈论坛的主旨发言人、崔莎· 布朗舞团的资深顾问苏珊 · 罗森伯格女士(以下简称S)。

W:今年国际舞蹈日,崔莎· 布朗是献词人。您能否先向我们介绍一下“献词人”是一个怎样的角色?

S:献词人通过每年舞蹈日的主题,例如今年的主题是“我们,一起舞”,向国际社会阐明舞蹈作为一种艺术形式的重要性,并表达其个人对于舞蹈的愿景。对于今年的献词人崔莎· 布朗而言,她的愿景构建于她50年的职业生涯之上。

W:的确,从献词人以自身在艺术领域的特殊贡献诠释舞蹈艺术的价值和含义的角度来说,崔莎· 布朗被选为今年的献词人是众望所归。您能否向我们介绍一下崔莎· 布朗?

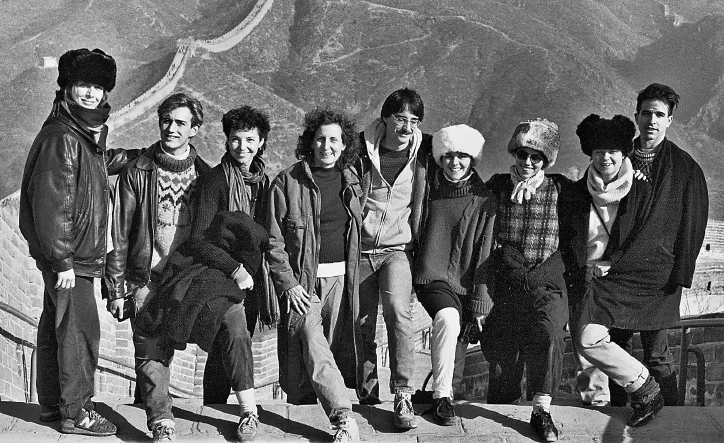

崔莎 · 布朗和她的舞团舞者于长城(1985年11月)摄影:肯恩 · 特巴契尼克Trisha Brown and her ensemble at the Great WallPhoto © Ken Tabachnick, November 1985

S:崔莎50年的舞蹈职业生涯是从一个在加利福尼亚和纽约两地工作的实验小组起步的。她在20世纪60年代开始了自己的事业,是最早定居在曼哈顿下城苏豪区“复式区”居民中的一员。1970年,她创办了自己的舞蹈团。创办之初,她就“不走寻常路”。例如在剧院外编排和表演,创作舞者走在建筑物外面的墙壁上的舞蹈作品,或在街道上、屋顶上进行表演。她对舞蹈动作有自己的概念和理解,脱离了传统意义上的“技艺精湛”,认为行走即舞蹈,或者说日常动态也可以成为舞蹈动作。然后她发明了自身独特的抽象舞蹈形态,通常用非常抽象的乐谱和舞谱来编舞。1978年,基于其作为舞者的非凡能力,她开始创造自己的舞蹈动作语言。之后她开始与美国最伟大的视觉艺术家合作,并将自己独创的舞蹈动作语言教授给其他舞者。

W:显然,崔莎是不拘泥于传统舞蹈的条条框框的。听说,崔莎 · 布朗小时候的数学非常棒,你觉得她是否将这一天分带入到舞蹈中?

S:我不知道她小时候有数学天赋,这是我头一次听说!的确,她在舞蹈中用过数学作为编舞结构原理,但这只在她职业生涯中持续了很短的时间,而且那段时间,许多艺术家,尤其是雕塑家,都会在自己的创作中运用数学作为结构原理。所以,其实只有1971 — 1975年间,她在编舞中运用了数学理念。崔莎从不基于音乐创作舞蹈,她的舞者也不数拍子,这一点在舞蹈作品中是十分少见的。因为舞者通常是根据音乐的节奏来舞动的,而她职业生涯前20年的大量作品是没有音乐的,没有任何音乐节拍。数学原理倒是在她编排的舞蹈结构中占有一席之地。

W:让我们聊聊她的舞蹈历程。崔莎是何时开始跳舞的?她在学习现代舞之前有没有经过正规的传统舞蹈训练?

S:嗯,崔莎从未学过芭蕾,但她学过她所在时代的所有主要的现代舞技巧。当她还是个小姑娘的时候,曾学过踢踏舞、爵士舞。她在美国西北部的一个沿海小镇长大,这些舞蹈当时在那儿比较流行。在我看来,从她的舞蹈中看不到任何经过正规传统训练的痕迹,因为她创造了一套她自己的舞蹈动作体系。她的身体有着极佳的柔韧性和自发性。由于她的思想和身体深度配合,可以说她发明了一些非常原创性的动作。所以她的舞蹈很难在之前的舞蹈中找寻到任何影子,她的确独一无二。

W:在她的舞蹈里,我们似乎看到很多与体操相关的元素,那么她是否曾经接触过体操或者类似的运动项目?

S:她没有学过体操。她在美国西北部的奥林匹克半岛长大,那里毗邻太平洋,有一片雨林。她儿时非常喜欢户外运动。她爬树、淌水,跟父亲去钓鱼和打猎。她非常热爱大自然。她常说雨林就是她的艺术学校。所以可以说她是从大自然中学习,在户外活运动中增长身体能力和运动能力的。她的哥哥是橄榄球和篮球的明星运动员。尽管她是一个女孩,他们也经常一起玩橄榄球。她的哥哥甚至尝试教她撑竿跳。所以她是非常运动型的人,但从来没有学过体操。1970年,她去了印度。她观看了印度马戏团的表演者做各种高空平衡动作,这对她而言很有吸引力,但她自己从未接受过正规的体操或者马戏团训练。

W:您前面提到了大自然对她的影响。在20世纪70年代后期,崔莎把日常生活的动作拿来当作舞蹈动作,场地也选择自然、开阔的空地。这是否与当时在艺术家和知识分子间盛行的东方禅宗思想有某种呼应?

S:这个问题很有意思。我不太清楚亚洲对她的舞蹈的影响。但给我印象最深的是,作曲家约翰· 凯奇对她影响很深。约翰是美国现代音乐界的泰斗之一,他把亚洲的哲学融入音乐和舞蹈。我也知道崔莎的舞者可能做了像太极一类的训练。他们试图在身体和即兴方面探索一些非西方的动作技巧。

W:崔莎的舞蹈经历,有学者将其分为四个阶段:结构即兴时期、装置时期、累积时期和放松技巧时期。在第一时期,即结构即兴时期,她加入了贾德逊舞蹈剧场。能否给我们介绍一下这个舞蹈剧场?

S:贾德逊舞蹈剧场实际上是由一个编舞班发展而来的。这个编舞班的老师是罗伯特· 邓恩,他是著名作曲家约翰 · 凯奇的学生。课程是教授班里的舞者和编导们约翰的音乐作曲理念。那个班级在纽约市中心华盛顿广场公园南面的贾德逊教堂举办了一系列汇报演出。崔莎参加了贾德逊舞蹈剧场。大家聚在一起,一起分享如何“为创作舞蹈创造新路子”(崔莎本人语),思考“当你摆脱了所有这些现有的创作方式时,你如何‘为创作舞蹈创造新路子’?”那个舞蹈剧场是一个展示新的舞蹈作品的地方,崔莎作为舞者参与了很多同事的作品—他们经常在彼此的作品中出现。那时,她的事业刚起步,也创作了几个作品在贾德逊教堂演出。在那里,他们经常在思考:“舞蹈到底是什么?”“什么可以成为舞蹈?舞蹈包含哪些要素?”在那里,人们也摒弃了陈旧的舞蹈定义。这就是贾德逊舞蹈剧场的实质所在。

W:贾德逊的舞蹈剧场被认为是美国现代舞试验的大本营。在当时的大背景下,崔莎的试验性舞蹈是否收到负面评价,甚至抵制?

S:是的。当我写书时,发现了一个在贾德逊舞蹈剧场不为人知的故事:来此观看演出的人大多是艺术家或者表演者的家人或朋友。所以偶尔纽约的报纸会写一篇评论,问类似于“这里到底在演些什么”的问题。但由于大多数观众都是表演者的朋友们,所以这些表演好评如潮。崔莎与贾德逊剧场的其他舞蹈家都很不同,她想带自己的作品参加在美国康涅狄格州新英格兰地区举办的现代舞艺术节。在这个现代舞艺术节上,玛莎· 格莱姆、艾瑞克· 霍金斯、默斯· 坎宁汉、多丽丝· 韩芙莉都会参加,各种大师派的技巧都会教授。崔莎把自己在纽约这种非常实验的情境下编排的舞蹈,也是她的第一个作品,带到艺术节去面试。我在我的研究过程中发现,这在当时引起了巨大的争端。艺术节一开始拒绝了她的作品参加,但学生们站起来说:“不,不,你们必须让它在舞蹈节上上演!”—学生们认为这个作品很精彩。这在当时的美国现代舞界掀起了一场巨大的争论。崔莎极力为自己辩护和争取,艺术节方面最终向崔莎做出妥协,“好吧,你可以参加这次舞蹈节,但你必须去掉你的配乐”—因为这配乐其实是吸尘器和一位女性的声音。可崔莎并没有让步:“除非有这个声音,否则我拒绝演出。”最终,她成功演出。她还记录下了这件事。我之后找到了她和当时在现场的一些人的信件记录。那是美国舞蹈节上第一件极具争议的事件。我相信崔莎当时是有意而为之的,她这么做就是想知道当时在现代舞领域的人们是如何看待她的作品的。此前她是无法知道的,因为当时纽约每个人都对她的作品表示赞赏并激动不已,但她把自己独创的舞蹈带到另一个地方,却发现让人们感到非常震惊。

W:崔莎对舞蹈的试验使一个简单的“走路”也变得不同寻常,其中《在墙上行走》是不得不提的作品。不论是舞者本身的表演、道具,所在的场馆,还是观众观看的角度和方式,都不同于传统意义上的舞蹈。能否给我们谈谈这个作品?

S:嗯,最初的版本叫《沿着墙壁向下行走的人》,完成于1970年,在崔莎所住的苏豪区的一座七层的大楼上。一位表演者从顶端开始,身上绑着绳索。他必须垂直于建筑物的外墙并向下走。这是一个利用重力却又对抗自然重力作用行走的实验作品—如果那位表演者顺循着重力,整个身体就会失控倾倒。所以他需要像在表演哑剧一样尽力使自己看起来走得很自然。这一舞蹈并不仅仅为了向世人展示“舞蹈作品中的步行”或“步行动作组成的舞蹈”,它凸显了这样一种理念:我们的身体实际上有很多肌肉记忆是我们不会琢磨的。但是如果让你的躯体垂直墙面行走,你必须问自己:“当我行走时,我的身体到底在做什么?步行是由什么组成的?”

这是崔莎的第一次试验。在此之后,她受邀在惠特尼博物馆演出。那次演出中,她修改了墙上行走,不再是向地面行走而是横向行走,由七位舞者完成。这一事件的重要性在于舞蹈在美国著名博物馆上演在当时是一种创举,也为如今博物馆舞蹈演出的普及化奠定了基础。与垂直于墙壁、地面即终点的行走不同,由于行走的方向是平行于地面,这就意味着舞者可以绕墙无休无止地行走,没有起点、中间点和终点。这让崔莎对行走又有了新的认知。观众也表示他们仿佛是从高处从上往下观看演员,因为身在地面的观众的确看到的是伸出墙外的舞者的头顶。这些便是崔莎早期最激进和危险的舞蹈动作尝试,挑战了身体的极限和日常行为的身体记忆。

崔莎 · 布朗和她的舞团舞者摄于长城(1985年11月)摄影:肯恩· 特巴契尼克Trisha Brown and her ensemble dancers at the Great Wall Photo © Ken Tabachnick, November 1985

W:之后,崔莎布朗进入了我们可以称之为“累积”的阶段。在这一时期,她创造了她最著名的那些编舞技法……

S:是的,从某种意义上说,我们之前谈论的舞蹈都是利用设备编排的舞蹈,比如《在墙上行走》,这一类是崔莎的代表性舞蹈作品。崔莎利用建筑原理进行编舞,这意味着她不需要做很多决定,她只是把这些设备安置好,就可以进行表演—绑上一些绳索,然后开始行走。她不认为在进行舞蹈编排时必须要作出很多复杂的、通常是主观的决定。她想找到一个更加客观的系统。她从数学中找到了“累积”系统:1, 1+2, 1+2+3, 1+2+3+4,……每次回到起点,从开始的动作做起。她编排了大约17支不同的舞蹈,使用各式累积编排不同舞蹈动作。我认为她的第一支累积作品,一支独舞,是她代表性的作品,因为她对编舞的体系进行了改造,使用不同的动作形式。有时表演者们会躺在地板上进行动作累积。这种舞蹈动作原理基于数学原理,就是她进行编舞的根据。崔莎认为这种动作原理是基于人体有三种解剖的可能性,即弯曲、拉伸和旋转,所有这些“累积”的舞蹈作品都使用了类似的解剖结构来探索这三种可能性不同形式的组合,以及由此编排出的舞蹈动作形式。我们觉得她的作品有着迷人的神秘感,我认为是在于它们匠心独具,而我们想象不出崔莎是如何决定出使用这些形式的。即使她说她没有做任何主观的决定,任由身体弯曲、伸展和旋转,并用数字进行编舞,其实对于使用何种形式的舞蹈动作,她做了很多主观的决定。对她最有吸引力、最具神秘色彩、我认为令她的舞蹈如此迷人的原因,也正是这些形式。

W:崔莎对传统舞蹈风格也有颠覆,《西班牙舞》与我们常见的弗拉明戈舞都不一样。它是怎样的一支舞蹈?

S:正如你所了解的那样,这个舞蹈要求五名舞者站成一排,舞蹈中最重要的部分是他们必须位于两堵墙之间,就像作品《沿着墙壁向下行走的人》一样,崔莎利用墙壁分隔时间与空间。这支舞蹈用了伟大的美国民谣歌手鲍勃· 迪伦的歌曲,不过是由艺术家戈登· 莱特福特演唱的,名叫《清晨雨》。舞者们变换位置,微微地转动臀部,然后一个舞者接续下一个舞者的动作:他们将双臂抬过头部,仿佛他们的上身在跳西班牙舞,下身只是不断摆动。这个舞蹈中的西班牙舞的元素是非常骄傲、戏剧化的。但当舞者紧靠在一起撞到墙壁,又是非常有趣的。这支舞蹈的创作意图就是有趣,同时尊重了像弗拉明戈或者其他西班牙舞蹈中的戏剧性,让人有“哇,看这舞蹈形式多炫目”的感叹,但又以极简主义的风格编排。她开玩笑地说,她在利用建筑来构建舞蹈的时间和空间。所以,我觉得崔莎在这个舞蹈中是有意地表现趣味性的。这支是她最流行也是被表演过最多次的舞蹈之一,这是有原因的。我认为其中一个原因是,虽然让身体有律动地舞蹈是很困难的,这支舞蹈要求表演者要有一定的音乐灵性,但不需要跳跃和旋转,所以各个年龄段的人都可以学习这支舞。

W:可见她是一个幽默的舞者,她自己也曾这么评价自己。在您看来,这种幽默从何而来?

S:是的,崔莎是一个很幽默、风趣、爱戏谑的人。当然,一位艺术家的性格会体现在她的作品里。崔莎喜欢使用双关语,她的很多舞蹈十分有趣。如果你观察细节,例如在她的作品《西班牙舞》中,舞者在做一些动作,然后“砰”的一声,他们撞到墙上,舞蹈就结束了。在一些舞蹈中,她会玩游戏,比如她会告诉她的舞者,让他们“自己消失”。当你在舞台上表演的时候,怎么可能让自己消失呢?于是那些舞者躺在地上,用手蒙住眼睛,好像你看不到他们,以此让自己“消失”。有时她编排一个需要两名舞者的动作,比如在《设置与重置》中,一位舞者会把手臂像这样摆着,另一人从中钻过去,当后来舞者重复这个动作时,不再有人从中钻过去。你如果看过这个作品的话,你会知道这是崔莎在开第一个动作的玩笑。她在排舞的过程中,给她舞者的一些指令也是非常有意思的。她可以用语言来编排舞蹈。她会对她的舞者们说:你去这里……做这个……做那个……性感些……来点卓别林的味道……从中激发动作的灵感,这就是她实验过程的一部分。最后,一些舞者会给这些滑稽的动作起外号。但她也会非常严肃,例如在根据巴赫的作品创作舞蹈时,她非常认真。但在编排她的第一部歌剧作品《奥菲欧》时,她曾告诉我,为了摆脱欧美歌剧的传统创作方式,她会把角色想象成卡通人物,让他们做非常夸张的事情。在她的心目中,她总是有很多有趣的想法,并设法让她的舞者完成体现这些想法的动作。

W:听说,在训练中她常会给舞者们一些“不可能完成的任务”,确实如此吗?

S:“不可能完成的任务”,这句话太棒了!我不知道你是哪里听来的,但是说得没错。从20世纪60年代初开始,新一代的舞者他们做结构即兴,给自己设定一个不可能完成的指令,然后看看会发生些什么。这样做的目的在于对下列问题的思考:创新如何实现?如果带着已经形成的想法是否能产生创新?所以,如果一开始告诉自己做一些完全不可能的事情,比如在五分钟或者五秒钟内,把身体的各部位叠成一条线,然后你的身体就会相应地做出反应。崔莎喜欢设想一些“不可能完成的”指令,然后告诉她的舞者,而往往出来的效果全是崭新的、独创的。或者她会有一些不可能的或看似不可能的想法,在她的引导下,她的舞者们真的可以实现它们。她曾经让她的两名舞者相向奔跑,想知道会产生什么样的效果。这样,在大脑意识到这些问题之前,身体已经解决了这些问题。我想到她在1978年创作舞蹈《水上机车》时,我记不清她给自己的确切指令是什么了,但是我记得她给自己一个口头的不可能完成的指令,试图达到一些奇特的效果,因为如果这些指令不可能达成,你起码能给出一些想象中的答案。所以说,她经常使用这种方式编舞。而且因为她经常通过舞动自己的身体琢磨出一些动作并教给她的舞者,可以说她用“不可能完成的任务”的理念去实现了“可能”。

W:崔莎的编舞与视觉艺术紧密联系,比如她曾在一张纸上跳舞的同时,用她的双脚画了一张画。这还是舞蹈吗?或者舞蹈与其他视觉艺术之间是否有明晰的界限?

S:“是否还是舞蹈?”这是一个很有意思的问题。我和崔莎最初认识就是因为合作一个项目,她把它叫作《这是一幅画》(It’s A Draw)。这是一个很能体现她幽默感的例子。因为在英语里“It’s a draw”的实际上是“打成平局”的意思,所以崔莎想表达舞蹈和视觉艺术之间打成平局:两者不分输赢,彼此地位平等,双方也相互竞争,谁也无法取代谁。这个标题体现出的是崔莎的幽默和智慧,因为崔莎将黑炭笔夹在她的手趾和脚趾间,用黑炭笔和油性笔,边舞蹈边作画。第一次表演这个节目的时候,她完全是即兴,倒在地面再站起来,脚趾间夹上黑炭笔跳踢踏舞。她在纸面上作画,留下精彩的痕迹,最终成为美丽的绘画作品,而她的身体在空间中作画。这些创作,无论是空间里的动作还是纸上的动作,无论是空中的动作还是舞台上的动作都并无大的差别。所以我认为她在玩一种概念,即不管动作是在空中还是被记录了下来,这些创作本质上没有区别—它们都是动作的符号,或是动作的轨迹。

W:崔莎· 布朗曾获得劳森伯格奖,而我们知道劳森伯格是美国波普艺术的代表人物,他们两人也是挚友。您是研究崔莎的专家,能否说说他们两人的关系?

S:崔莎第一次见到劳森伯格是在她搬去纽约之后不久。她告诉过我,也告诉过很多人,那时候她还是在默斯· 坎宁汉舞团半工半读的一名学生,她的工作是接电话。劳森伯格当时担任舞团的艺术总监,与默斯· 坎宁汉和约翰· 凯奇都很熟。劳森伯格时常打电话到团里,他和崔莎很多次在电话里都交谈甚欢。当时崔莎并不知道他是谁,但他们已经建立了默契。1963年,崔莎参观劳森伯格在犹太展览馆里举行的作品回顾展时,她才惊讶地发现,“天呐!劳森伯格原来是美国一位非常著名的艺术家!”这是劳森伯格第一个大型作品展,他当时正在逐步建立自己的事业。此后他们一直是朋友。劳森伯格在20世纪60年代中期开始涉足舞蹈圈,有时自己创作舞蹈作品,有时表演其他人的作品。崔莎在1979年登上剧院舞台,她第一个想到要合作的人便是劳森伯格。那时,在一段长时期的合作之后,他已经离开了默斯 · 坎宁汉舞团。崔莎与劳森伯格之间的友情,我不确定能够完全描述出来。总之,他们之间的关系非常特别,一部分是因为他们都比较幽默,另一方面是基于他们的“美国关联”—比如崔莎曾经跟我说,她在美国西北部靠近太平洋的家乡,感恩节时她家里人会给她送冻三文鱼,而劳森伯格由于来自得克萨斯,他家人会给他送冻火鸡,诸如此类的事情。崔莎与劳森伯格一共合作过五部作品,劳森伯格负责设计舞美和服装。1979年,他们首次合作作品《冰川的诱惑》。之后是《如果你看不见我》,其想法来源于劳森伯格。该作品将于明晚在上海“2017国际舞蹈日庆典之夜”演出,这是他们之间最简单的一次合作。他们早期的合作内容涉及摄影、摄像和灯光,而劳森伯格的服装设计甚至包括丝印服装。劳森伯格为崔莎的四部作品进行了舞台设计。此次2017国际舞蹈日上演的作品是两人合作的最后一部作品,让崔莎· 布朗背对着观众跳舞的主意也是劳森伯格想的。或者应该说,劳森伯格为这支舞蹈制定了规则,要求崔莎编排一个背对着观众的舞蹈。崔莎当时非常惊讶,“如果我背对着观众,观众不会觉得我很无礼吗?”劳森伯格还为该作品设计了音乐和服装。

W:我们都知道今年国际舞蹈日崔莎· 布朗的献词是您整理的。作为她的密友,在您看来,她是一个怎样的人?

S:崔莎 · 布朗是我迄今为止见过最非凡的人。她非常聪明!有些人思维敏捷,另外一些人协调性好,而崔莎两者兼备。她的幽默也很特别,正是因为她是一位身心深度结合的人,所以她可以用她的身体诉说,无人能及。作为一位有如此惊人的、伟大的、辉煌的成就以及艺术贡献的人,她又是如此善良,如此谦虚。她的艺术体现着她这样的想法—“当我登上舞台,你能感觉到我是一个活生生的人,你能感觉到我的人性。你看到我呼吸,看到我在看着你。”无论是舞台上还是现实生活中,她皆是如此。她关爱她的舞者,对于他们的切身利益都非常关注。她的献词来源于过去一些场合中她对艺术的一些评论。正如她的献词所说,她对艺术对于人类的重要性深信不疑。她认为,舞蹈作为一种非语言的艺术形式,在连结不同的文化、社会中起着特殊的作用。这也是崔莎一直想要传达的信息之一。

W:谢谢您接受我们的访问,让我们能够如此接近崔莎· 布朗这位舞蹈艺术大师和她的舞蹈作品!

(中文翻译:邬钧宜、汤益明 责任编辑:刘青弋、孙晓弋)

About the Author:Susan Rosenberg, female, Consulting Historical Scholar at the Trisha Brown Dance Company, Director of the Master’s Degree Program for the Museum Administration of St. John’s University in New York, Associate Prof essor of Art History.Research interests: dance choreography, art history, and visual art studies. WU Jun-yi, female, reporter at Shanghai Media Group.