退变性脊柱侧凸术后骨盆投射角与腰椎前凸角匹配程度与临床疗效的关系

2017-01-19孙祥耀张希诺海涌

孙祥耀 张希诺 海涌

退变性脊柱侧凸术后骨盆投射角与腰椎前凸角匹配程度与临床疗效的关系

孙祥耀 张希诺 海涌

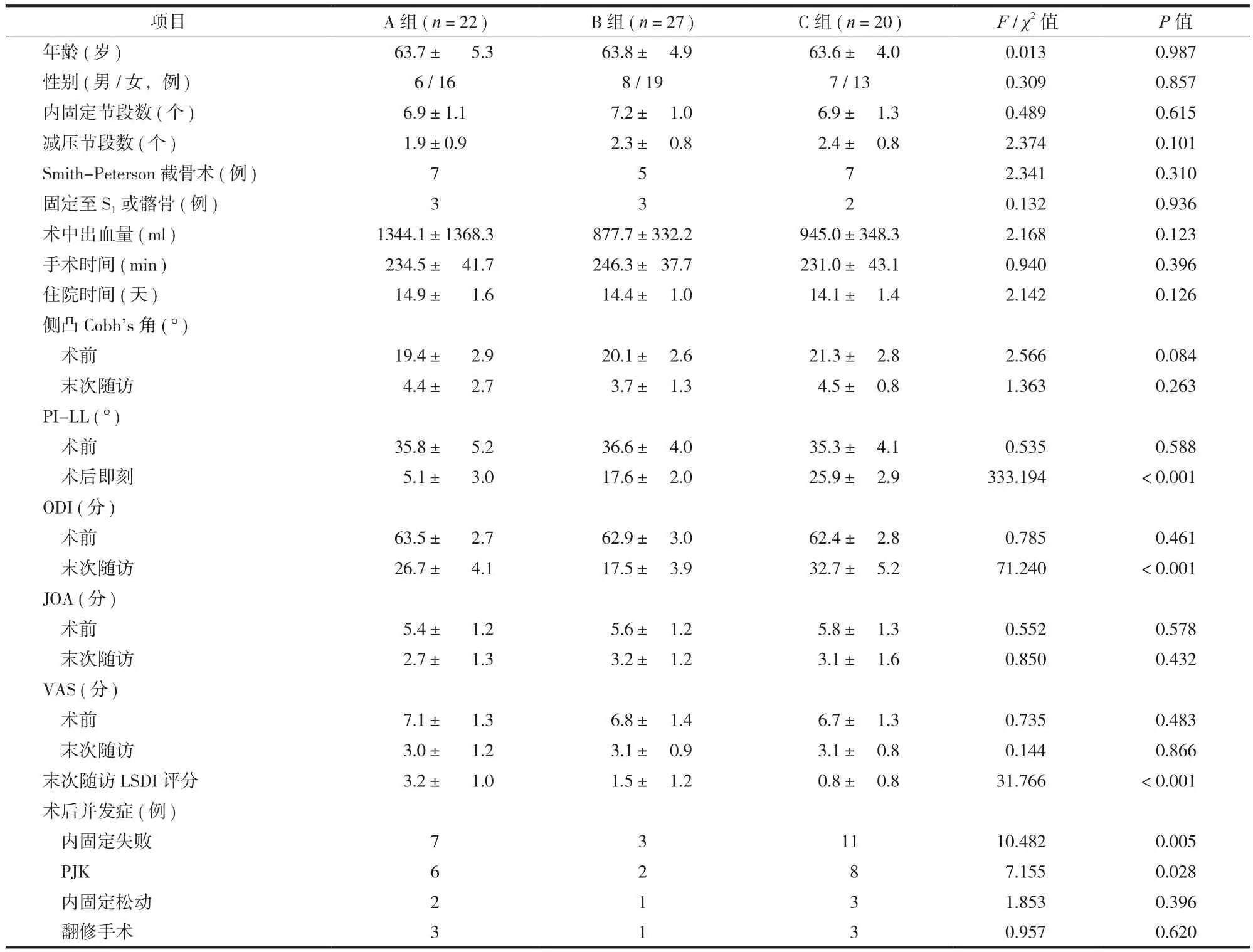

目的评估术后即刻骨盆投射角与腰椎前凸角匹配程度 ( the mismatch between pelvic incidence and lumbar lordosis,PI-LL ) 矫正至不同范围与术后脊柱侧凸矫正度、生活质量及内固定失败的关系。方法回顾性研究 2010 年 1 月至 2014 年 1 月,我院行后路长节段椎弓根螺钉内固定植骨融合治疗的 69 例成人退变性脊柱侧凸 ( adult degenerative scoliosis,ADS ) 患者,其中男 21 例,女 48 例,平均年龄 ( 63.7±4.7 ) 岁,随访时间均>2 年,平均 ( 3.2±0.7 ) 年。将患者进一步分为 A 组 ( PI-LL≤10° )、B 组 ( PI-LL>10°~≤20° )、C 组 ( PI-LL>20° )。测量术前、术后及末次随访时患者矢状位影像学参数并计算 PI-LL,评估术前及末次随访时患者的生活质量 [ 日本骨科协会评分 ( Japanese Orthopaedic Association,JOA )、Oswestry 功能障碍指数 ( oswestry disability index,ODI )、疼痛视觉模拟评分 ( visual analogue scale,VAS )、腰椎僵硬功能障碍指数( lumbar stiffness disability index,LSDI ) ],并进行统计学分析比较。曲线分析比较术后 PI-LL 与临床疗效以及影像学参数的相互关系。结果A 组术前脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角 ( 19.4±2.9 ) °、PI-LL ( 35.8±5.2 ) °、ODI 评分( 63.5±2.7 ) 分、JOA 评分 ( 5.4±1.2 ) 分、VAS 评分 ( 7.1±1.3 ) 分,术后即刻 PI-LL ( 5.1±3.0 ) °,末次随访脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角 ( 4.4±2.7 ) °、ODI 评分 ( 26.7±4.1 ) 分、JOA 评分 ( 2.7±1.3 ) 分、VAS 评分 ( 3.0± 1.2 ) 分、LSDI 评分 ( 3.2±1.0 ) 分。B 组术前脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角 ( 20.1±2.6 ) °、PI-LL ( 36.6±4.0 ) °、ODI 评分 ( 62.9±3.0 ) 分、JOA 评分 ( 5.6±1.2 ) 分、VAS 评分 ( 6.8±1.4 ) 分,术后即刻 PI-LL ( 17.6±2.0 ) °,末次随访脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角 ( 3.7±1.3 ) °、ODI 评分 ( 17.5±3.9 ) 分、JOA 评分 ( 3.2±1.2 ) 分、VAS 评分 ( 3.1± 0.9 ) 分、LSDI 评分 ( 1.5±1.2 ) 分。C 组术前脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角 ( 21.3±2.8 ) °、PI-LL ( 35.3±4.1 ) °、ODI 评分 ( 62.4±2.8 ) 分、JOA 评分 ( 5.8±1.3 ) 分、VAS 评分 ( 6.7±1.3 ) 分,术后即刻 PI-LL ( 25.9±2.9 ) °,末次随访脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角 ( 4.5±0.8 ) °、ODI 评分 ( 32.7±5.2 ) 分、JOA 评分 ( 3.1±1.6 ) 分、VAS 评分 ( 3.1± 0.8 ) 分、LSDI 评分 ( 0.8±0.8 ) 分。术后与术前相比,脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角、PI-LL、JOA、ODI、VAS 均明显改善,差异有统计学意义 ( P<0.001 )。各组间术后即刻 PI-LL 差异有统计学意义 ( P<0.001 ),其它影像学指标差异无统计学意义。在患者生活质量比较方面,除末次随访 ODI 和 LSDI 差异有统计学意义以外 ( P<0.001 ),其它指标差异均无统计学意义。B 组内固定失败发生率较 A 组和 C 组低 ( P=0.005 ),翻修率差异无统计学意义 ( P=0.620 )。S 方程符合 PI-LL 与术后 Cobb’s 角的相关性 ( R2=0.416,P<0.001 ),三次方程符合 PI-LL 与末次随访 ODI ( R2=0.370,P<0.001 )、末次随访 LSDI 的相关性 ( R2=0.720,P<0.001 ),而 PI-LL 与其它指标之间的相关性无统计学意义 ( P>0.05 )。结论在后路长节段内固定融合术治疗 ADS 后,将术后 PI-LL 矫正到 10°~20° 之间,临床疗效最好,并且能够明显降低术后内固定相关并发症的发生率。过多矫正 LL 使PI-LL 过低,可能会增加术后腰椎僵硬程度。

脊柱侧凸;骨盆参数;生活质量;脊柱融合术

成人退变性脊柱侧凸 ( adult degenerative scoliosis,ADS ) 被定义为骨骼发育成熟而之前未出现脊柱侧凸病史者出现脊柱冠状位侧凸,角度>10°[1]。年龄>50 岁者多发,据报道其患病率高达 60%[2]。通常伴有腰背部疼痛、神经功能障碍,以及运动功能障碍,从而严重影响患者的生活质量[3]。因此,对冠状位侧凸的矫正成为治疗的主要目的[4]。在治疗过程中,通常优先考虑保守治疗,然而保守治疗效果往往较差[5]。在合理评估手术风险之后,采用后路长节段固定融合的方法治疗 ADS 较为安全有效[6]。

近来有研究指出,在制订治疗计划方面,矢状位失平衡的指标比冠状面失平衡更有意义,因此退变性脊柱侧凸的矢状位脊柱骨盆参数的评估得到了广泛关注[7-8]。其中骨盆投射角与腰椎前凸角匹配程度 ( the mismatch between pelvic incidence and lumbar lordosis,PI-LL ) 是较为理想的参考指标,这是因为在骨骼发育成熟以后,骨盆投射角 ( pelvic incidence,PI ) 为相对恒定的解剖参数,因此在治疗过程中只需调整腰椎前凸角 ( lumbar lordosis,LL ) 与 PI 进行匹配即可达到理想的平衡状态[9-10]。Schwab 等[11-12]指出,成人脊柱畸形理想的 PI-LL 应当为 -10°~10°。然而,Yamada 等[13]在其研究中指出,即使不矫正 PI-LL,有 23% 的患者也能获得很好的临床疗效。本回顾性研究基于 SRS-Schwab 分型 ( Scoliosis Research Society-Schwab )[12],对 2010 年1 月至 2014 年 1 月,于我院行后路长节段椎弓根螺钉内固定植骨融合治疗的 ADS 患者进行分类比较,旨在通过多组比较及曲线分析,对术后 PI-LL 大小与各临床疗效指标的相关性进行进一步探索。

资料与方法

一、入组与排除标准

1. 入组标准:( 1 ) 年龄>45 岁;( 2 ) 腰椎侧凸角≥10°;( 3 ) 进行 3 个运动单位以上的内固定融合手术,从胸椎固定至 L5或骶骨;( 4 ) 使用第三代全椎弓根螺钉内固定系统;( 5 ) 有完整的临床资料和术前、术后、末次随访的站立位脊柱全长正侧位X 线片;( 6 ) 随访时间>2 年。

2. 排除标准:( 1 ) 有其它腰部手术史;( 2 ) 存在其它类型的脊柱侧凸;( 3 ) 严重脊柱外伤史、脊柱肿瘤、强直性脊柱炎、脊柱结核等。

二、一般资料

本组共纳入 69 例 ADS 患者,其中男 21 例,女 48 例,平均年龄 ( 63.7±4.7 ) 岁,融合节段 4~10 个,平均 ( 7.0±1.1 ) 个。根据 SRS-Schwab 分型将患者被进一步分为 A 组 ( PI-LL≤10° )、B 组( PI-LL>10°~≤20° )、C 组 ( PI-LL>20° )。其中A 组 22 例,B 组 27 例,C 组 20 例。3 组一般情况差异无统计学意义 ( 表1 )。

三、研究方法

1. 影像学测量:对纳入研究的患者均拍摄术前、术后即刻以及末次随访脊柱全长正侧位 X 线片。测量的矢状位脊柱骨盆参数包括:( 1 ) 脊柱侧凸节段 Cobb’s 角;( 2 ) PI:S1上终板经中点垂线和S1上终板中点至股骨头中点连线的夹角;( 3 ) LL:L1上终板与 S1上终板间的 Cobb’s 角;( 4 ) PI-LL:骨盆投射角与腰椎前凸角之差。

2. 临床疗效评估:通过收集患者日本骨科协会评分 ( Japanese Orthopaedic Association,JOA )、Oswestry 功能障碍指数 ( oswestry disability index,ODI )、疼痛视觉模拟评分 ( visual analogue scale,VAS )、腰椎僵硬功能障碍指数 ( lumbar stiffness disability index,LSDI ) 以及住院时间,对患者的临床疗效进行评估比较。

3. 手术情况:对患者术中出血量、手术时间、并发症情况、融合节段数以及减压节段数量进行统计分析。

四、统计学处理

采用 SPSS 17.0 软件对数据进行统计学分析。计量资料使用±s 表示,计数资料用百分比表示。使用 Kolmogorov-Smirnov 检验连续性变量是否符合正态分布,符合正态分布的变量使用 F 检验进行多重比较,偏态分布变量采用 Kruskal-Walllist 检验进行分析。非连续变量使用 χ2检验进行比较。曲线分析用于比较术后 PI-LL 与临床疗效以及影像学参数的相互关系。P<0.05 为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

所有患者均采用第三代全椎弓根螺钉内固定系统。平均手术时间 ( 238.1±40.6 ) min,出血量( 1045.9±835.1 ) ml,住院时间 ( 14.5±1.4 ) 天 ( 表1 )。

术前统计所得相关指标:脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角( 20.2±2.8 ) °,PI-LL ( 36.0±4.4 ) °,JOA ( 5.6± 1.2 ) 分,ODI ( 62.9±2.8 ) 分,VAS ( 6.9±1.3 ) 分。术后所得相关指标:Cobb’s 角 ( 4.1±1.8 ) °,PI-LL ( 16.0±8.6 ) °,JOA ( 3.0±1.6 ) 分,ODI ( 24.8± 7.7 ) 分,VAS ( 3.1±1.0 ) 分。术后与术前相比,脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角、PI-LL、JOA、ODI、VAS 等影像学与功能指标均明显改善,差异有统计学意义( P<0.001 ),但是并非所有患者都达到理想 PI-LL ( PI-LL≤10° )[11]。

在术后影像学指标中,术后即刻 PI-LL 组间差异有统计学意义 ( P<0.001 ),其它影像学指标差异无统计学意义 ( 表1 )。在患者生活质量比较方面,除末次随访 ODI 和 LSDI 差异有统计学意义 ( P<0.001 ),其它指标差异均无统计意义 ( 表1 )。

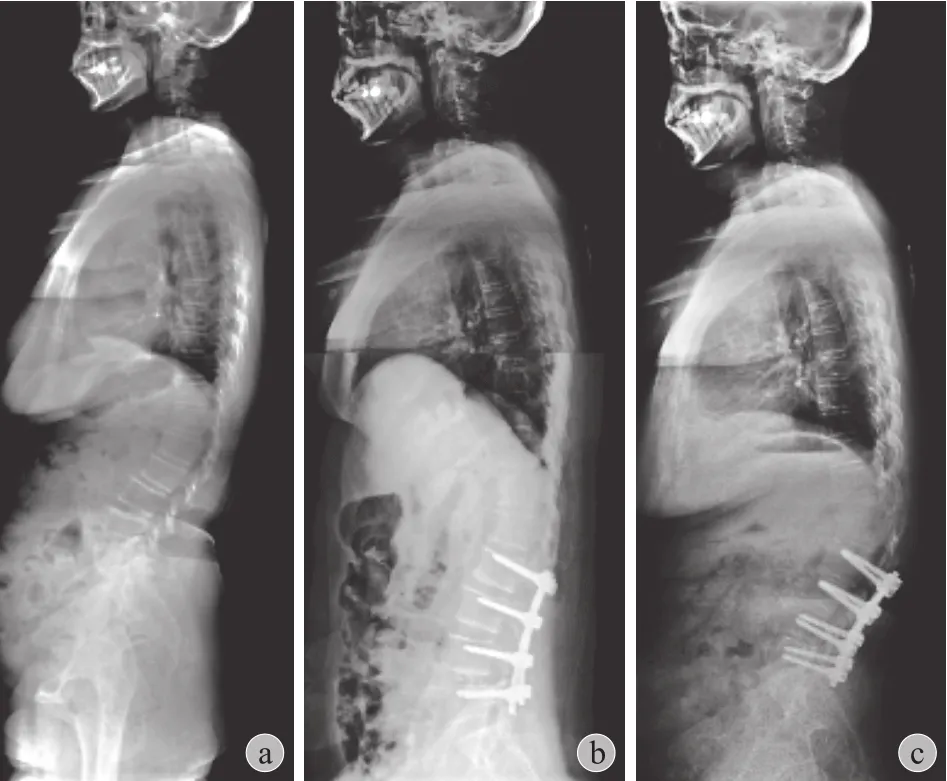

此外,本研究对手术并发症患者的信息进行了收集整理,包括近端交界性后凸 ( proximal iunctional kyphosis,PJK ) 形成 16 例 ( 23.2% ) ( 图 1 ),内固定松动 6 例 ( 8.7% );PJK 患者中 4 例因后凸角度较大,有明显的下腰痛及下肢症状而进行了翻修手术;内固定松动患者中 3 例因明显局部疼痛而进行了翻修手术。B 组内固定失败发生率较 A 组和 C 组低 ( P=0.005 ),其中 PJK 发生率的差异有统计学意义 ( P=0.028 ),而内固定松动的发生率差异无统计学意义 ( P=0.396 ),翻修率差异无统计学意义 ( P=0.620 ) ( 表1 )。

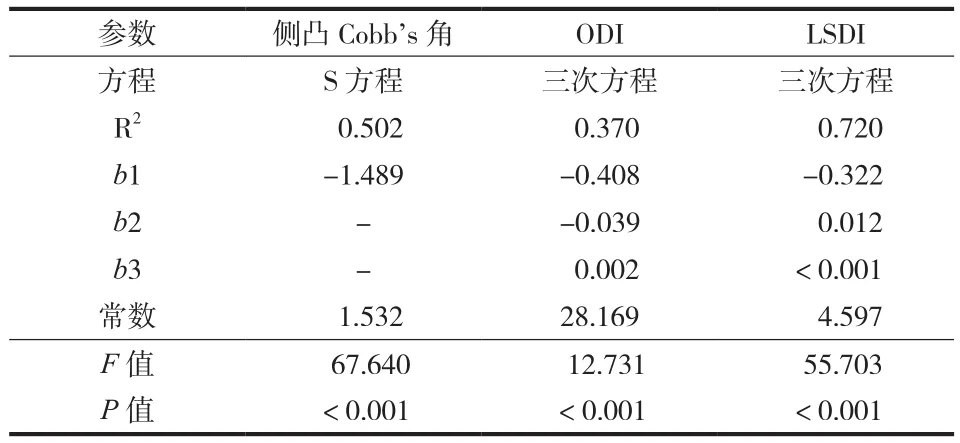

以 PI-LL 为自变量,末次随访脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s角、ODI、JOA、VAS、LSDI 为因变量分别进行曲线分析,结果提示 S 方程符合 PI-LL 与术后 Cobb’s 角( R2=0.416,P<0.001 ) 的关系,三次方程符合 PI-LL与末次随访 ODI ( R2=0.370,P<0.001 ) 、末次随访LSDI 的关系 ( R2=0.720,P<0.001 ),而 PI-LL 与其它指标之间的相关性均较低 ( P<0.05 ) ( 表2 )。

表1 3 组患者一般情况及临床资料比较 (±s)Tab.1 Comparison of patients’ demographic and clinical parameters among the 3 groups (±s)

表1 3 组患者一般情况及临床资料比较 (±s)Tab.1 Comparison of patients’ demographic and clinical parameters among the 3 groups (±s)

注:ODI:Oswestry 功能障碍指数;JOA:日本骨科协会评分;VAS:视觉模拟评分;LSDI:腰椎僵硬功能障碍指数Notice: ODI: Oswestry disability index; JOA: Japanese Orthopaedic Association; VAS: visual analogue scale; LSDI: lumbar stiffness disability index

项目 A 组 ( n=22 ) B 组 ( n=27 ) C 组 ( n=20 ) F / χ2值 P 值年龄 ( 岁 ) 63.7± 5.3 63.8± 4.9 63.6± 4.0 0.013 0.987性别 ( 男 / 女,例 ) 6 / 16 8 / 19 7 / 13 0.309 0.857内固定节段数 ( 个 ) 6.9±1.1 7.2± 1.0 6.9± 1.3 0.489 0.615减压节段数 ( 个 ) 1.9±0.9 2.3± 0.8 2.4± 0.8 2.374 0.101 Smith-Peterson 截骨术 ( 例 ) 7 5 7 2.341 0.310固定至 S1或髂骨 ( 例 ) 3 3 2 0.132 0.936术中出血量 ( ml ) 1344.1±1368.3 877.7±332.2 945.0±348.3 2.168 0.123手术时间 ( min ) 234.5± 41.7 246.3± 37.7 231.0± 43.1 0.940 0.396住院时间 ( 天 ) 14.9± 1.6 14.4± 1.0 14.1± 1.4 2.142 0.126侧凸 Cobb’s 角 ( ° )术前 19.4± 2.9 20.1± 2.6 21.3± 2.8 2.566 0.084末次随访 4.4± 2.7 3.7± 1.3 4.5± 0.8 1.363 0.263 PI-LL ( ° )术前 35.8± 5.2 36.6± 4.0 35.3± 4.1 0.535 0.588术后即刻 5.1± 3.0 17.6± 2.0 25.9± 2.9 333.194 <0.001 ODI ( 分 )术前 63.5± 2.7 62.9± 3.0 62.4± 2.8 0.785 0.461末次随访 26.7± 4.1 17.5± 3.9 32.7± 5.2 71.240 <0.001 JOA ( 分 )术前 5.4± 1.2 5.6± 1.2 5.8± 1.3 0.552 0.578末次随访 2.7± 1.3 3.2± 1.2 3.1± 1.6 0.850 0.432 VAS ( 分 )术前 7.1± 1.3 6.8± 1.4 6.7± 1.3 0.735 0.483末次随访 3.0± 1.2 3.1± 0.9 3.1± 0.8 0.144 0.866末次随访 LSDI 评分 3.2± 1.0 1.5± 1.2 0.8± 0.8 31.766 <0.001术后并发症 ( 例 )内固定失败 7 3 11 10.482 0.005 PJK 6 2 8 7.155 0.028内固定松动 2 1 3 1.853 0.396翻修手术 3 1 3 0.957 0.620

图1 患者,女,62 岁,ADS 畸形,矢状位 X 线片 a:术前存在胸腰段退变性后凸;b:术后即刻 PI-LL 为 23°;c:随访 2年,矢状位 PJK 形成,为 28°Fig.1 This was a 62-year-old woman with ADS, and these were sagittal X-ray films a: Thoracolumbar kyphosis was noticed before the operation; b: Immediate postoperative PI-LL was 23°; c: PJK was 28° at 2 years’ follow-up

讨 论

尽管以往研究表明了 PI-LL 对于指导手术治疗的重要性[14-16],但是仍有很多研究对最佳 PI-LL的选择提出质疑[13,17]。目前,尚缺乏适用于国人的PI-LL 矫形金标准,因此本研究基于 SRS-Schwab 分型中的 PI-LL 矢状位矫正分类[12]对后路长节段固定融合术治疗 ADS 患者进行分组,对其术后 PI-LL与临床疗效的相关性进行比较。在比较影像学参数的过程中发现,末次随访脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角虽然在3 组中差异无统计学意义 ( P=0.263 ),但是各组末次随访脊柱侧凸 Cobb’s 角仍然<10°,表明其在冠状面的矫形是有效的。Schwab 等[18]将退变性脊柱侧凸患者分为手术组及非手术组进行研究,并将两者的矢状位参数进行比较,发现其 PI-LL 差异有统计学意义,并指出 PI-LL>11° 与 ODI 评分>40 分之间有相关性。与以往研究结论不同,本研究发现术后 PI-LL 大小为 10°~20° 的患者相比其他患者ODI 评分更低,而 JOA 评分以及 VAS 评分相对而言无明显差异,表明其能达到理想的临床疗效。关于PI-LL 的理想矫正度方面尚无定论,有研究指出应当将 PI-LL 矫正至 11° 以下[18];然而关于脊柱骨盆矢状位重建的研究指出,ASD 患者术后影像学参数应当符合 LL=PI±9°[11]。因此,本研究所得结论与经典的矢状重建理论并不一致。Schwab 等[18]在其研究中纳入患者平均年龄为 51.9 岁,而本研究纳入患者平均年龄为 63.7 岁,整体年龄相对较大。Xu等[19]对 296 名中国成人的脊柱骨盆参数进行了前瞻性研究,通过进行线性回归分析发现 LL 与 PI 和年龄相关。Lafage 等[20]研究发现,脊柱骨盆参数随着年龄的增加会发生变化,并指出年龄<35 岁的患者最佳 PI-LL 为 -10.5°,而年龄>75 岁者,其最佳PI-LL 为 16.7°。Zhu 等[21]对 260 名汉族成人进行了脊柱骨盆参数的研究,指出脊柱骨盆参数受年龄、体重、性别的影响,种族不同,脊柱骨盆参数也会有较大差异。Banno 等[22]研究发现,女性 PI-LL 较男性大,并且会随着年龄的增加而增大。Inami 等[17]指出 PI-LL 与预期的临床疗效有时出现偏差,这可能与 PI 的个体化差异有关。因此,本研究结果与既往研究不同可能为本研究纳入患者平均年龄较高,纳入患者女性比例较大,与既往研究纳入患者的种族差异所致。

表2 患者术后 PI-LL 与术后临床疗效曲线分析Tab.2 Curve estimation in evaluating the relationship between postoperative PI-LL and Cobb angle, ODI and LSDI

矢状位脊柱骨盆参数与生活质量的关系一直存在争议。Chaleat-Valayer 等[23]对 198 例慢性下腰痛患者与 709 名无症状成人进行回顾性研究,指出慢性下腰痛与较小的 PI、骶骨倾斜角 ( sacral slope,SS )、LL 有关,而与骨盆倾斜角 ( pelvic tilt,PT ) 无关。Mac-Thiong 等[24]研究表明,ADS 患者 ODI 评分与其 SVA ( C7铅垂线与骶骨后上角之间的距离 )有相关性。Schwab 等[11]指出 ADS 患者术后 PI-LL处于 -10°~10° 时,ODI 评分明显优于不在此范围的患者。然而,既往常用的评分系统无法较好地体现脊柱僵硬对功能的影响。Hart 等[25]通过使用 LSDI评分对 32 例腰椎融合术后患者进行随访研究,并指出 LSDI 评分对腰椎融合术后患者的腰部僵硬和功能受限有较高的价值。Deniels 等[26]将 LSDI 评分应用于 ADS 患者的研究中,通过对多中心 176 名健康志愿者及 693 例患者的研究,发现脊柱僵硬引起的功能障碍与疼痛引起的功能障碍有相关性。Sciubba等[27]对 134 例 ADS 患者进行回顾性研究,使用LSDI 评分进行术后功能评估,发现固定融合至上胸椎的患者在进行清洁下身、穿裤等动作时明显受限,而是否融合至髂骨对 LSDI 结果影响较小。本研究曲线分析的结果表明 PI-LL 与 LSDI 成负相关,而PI 为固定值[18],则可说明术中矫正 LL 使之过大,可能会使术后腰椎僵硬程度增加。

针对 ADS 患者术后内固定松动及假关节形成对临床疗效影响的研究较少,但是既往针对内固定失败方面的研究表明,内固定松动对临床疗效无严重影响[28]。本研究中同样有患者出现内固定松动,根据患者相应临床表现,选择是否进行翻修手术治疗。Cho 等[29]认为,PI、SVA 较大,LL 矫正不佳的患者,在 ADS 后路长节段内固定术后出现内固定失败发生率较高。PKJ 在 ADS 手术治疗的并发症中并不少见[30]。Kim 等[31]对 206 例进行回顾性研究,随访 2 年,PJK 发生率高达 34%;其研究表明 LL 矫正较多,矢状位平衡变化较大的患者更易在术后出现 PJK。相关研究表明,PI-LL>10° 会使邻近节段病变发生以及再手术的发生率增加 10 倍左右[32]。而本研究中 B 组并发症总体发生率较 A 组和 C 组低,内固定失败发生率较低,明显减低 PJK 发生率。因此,在 ADS 的矫形中将 PI-LL 调整在 10°~20° 能够降低内固定失败的风险,降低再手术的发生率。

综上所述,目前适合国人的 PI-LL 范围尚有争议,并且有相关研究指出 PI 值大小有种族差异[17,21-22]。因此,既往研究按照 PI-LL≤10° 及PI-LL>10° 对患者进行分组研究并不完全适用于国人体质[11,18]。本研究表明,在后路长节段内固定融合术治疗 ADS 后,将术后 PI-LL 矫正到 10°~20° 之间,临床疗效最好,并且能够明显降低术后内固定相关并发症的发生率。PI-LL 与 LSDI 呈负相关,过度矫正使 LL 过大,PI-LL 过小可能加重术后腰椎僵硬程度,而 PI-LL 与其它指标之间的线性相关性均较低。然而,本研究尚存在不足:首先,本研究为回顾性研究,存在选择偏倚;其次,样本量较少。因此,为了进一步明确国人 PI-LL 的最佳大小以及PI-LL 与临床疗效的关系,仍然需要进行大样本前瞻性研究。

[1] Glassman SD, Berven S, Bridwell K, et al. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis[J]. Spine, 2005, 30(6):682-688.

[2] Hosogane N, Watanabe K, Tsuji T, et al. Serum cartilage metabolites as biomarkers of degenerative lumbar scoliosis[J]. J Orthop Res, 2012, 30(8):1249-1253.

[3] Pellise F, Vila-Casademunt A, Ferrer M, et al. Impact on health related quality of life of adult spinal deformity (ASD) compared with other chronic conditions[J]. Eur Spine J, 2015, 24(1):3-11.

[4] Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, et al. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity[J]. Spine, 2005, 30(18):2024-2029.

[5] Transfeldt EE, Topp R, Mehbod AA, et al. Surgical outcomes of decompression, decompression with limited fusion, and decompression with full curve fusion for degenerative scoliosis with radiculopathy[J]. Spine, 2010, 35(20):1872-1875.

[6] Cho KJ, Kim YT, Shin SH, et al. Surgical treatment of adult degenerative scoliosis[J]. Asian Spine J, 2014, 8(3):371-381.

[7] Nishimura Y, Hara M, Nakajima Y, et al. Outcomes and complications following posterior long lumbar fusions exceeding three levels[J]. Neurol Med Chir, 2014, 54(9): 707-715.

[8] Barrey C, Roussouly P, Perrin G, et al. Sagittal balance disorders in severe degenerative spine. Can we identify the compensatory mechanisms[J]? Eur Spine J, 2011, 20(Suppl 5): 626-633.

[9] Legaye J, Duval-Beaupere G, Hecquet J, et al. Pelvic incidence: a fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves[J]. Eur Spine J, 1998, 7(2):99-103.

[10] Diebo BG, Henry J, Lafage V, et al. Sagittal deformities of the spine: factors infuencing the outcomes and complications[J]. Eur Spine J, 2015, 24(Suppl 1):S3-15.

[11] Schwab F, Patel A, Ungar B, et al. Adult spinal deformitypostoperative standing imbalance: how much can you tolerate? An overview of key parameters in assessing alignment and planning corrective surgery[J]. Spine, 2010, 35(25):2224-2231.

[12] Schwab F, Ungar B, Blondel B, et al. Scoliosis Research Society-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: a validation study[J]. Spine, 2012, 37(12):1077-1082.

[13] Yamada K, Abe Y, Yanagibashi Y, et al. Mid- and long-term clinical outcomes of corrective fusion surgery which did not achieve suffcient pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis value for adult spinal deformity[J]. Scoliosis, 2015, 10(Suppl 2):S17. [14] Smith JS, Klineberg E, Schwab F, et al. Change in classifcation grade by the SRS-Schwab Adult Spinal Deformity Classification predicts impact on health-related quality of life measures: prospective analysis of operative and nonoperative treatment[J]. Spine, 2013, 38(19):1663-1671.

[15] Aoki Y, Nakajima A, Takahashi H, et al. Influence of pelvic incidence-lumbar lordosis mismatch on surgical outcomes of short-segment transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion[J]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2015, 16:213.

[16] Ha KY, Jang WH, Kim YH, et al. Clinical relevance of the SRS-Schwab classifcation for degenerative lumbar scoliosis[J]. Spine, 2016, 41(5):E282-288.

[17] Inami S, Moridaira H, Takeuchi D, et al. Optimum pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis value can be determined by individual pelvic incidence[J]. Eur Spine J, 2016, 25(11): 3638-3643.

[18] Schwab FJ, Blondel B, Bess S, et al. Radiographical spinopelvic parameters and disability in the setting of adult spinal deformity: a prospective multicenter analysis[J]. Spine, 2013, 38(13):E803-812.

[19] Xu L, Qin X, Zhang W, et al. Estimation of the ideal lumbar lordosis to be restored from spinal fusion surgery: a predictive formula for Chinese population[J]. Spine, 2015, 40(13): 1001-1005.

[20] Lafage R, Schwab F, Challier V, et al. Defining spino-pelvic alignment thresholds: should operative goals in adult spinal deformity surgery account for age[J]? Spine, 2016, 41(1): 62-68.

[21] Zhu Z, Xu L, Zhu F, et al. Sagittal alignment of spine and pelvis in asymptomatic adults: norms in Chinese populations[J]. Spine, 2014, 39(1):E1-6.

[22] Banno T, Togawa D, Arima H, et al. The cohort study for the determination of reference values for spinopelvic parameters (T1 pelvic angle and global tilt) in elderly volunteers[J]. Eur Spine J, 2016, 25(11):3687-3693.

[23] Chaleat-Valayer E, Mac-Thiong J M, Paquet J, et al. Sagittal spino-pelvic alignment in chronic low back pain[J]. Eur Spine J, 2011, 20(Suppl 5):634-640.

[24] Mac-Thiong JM, Transfeldt EE, Mehbod AA, et al. Can c7plumbline and gravity line predict health related quality of life in adult scoliosis[J]? Spine, 2009, 34(15):E519-527.

[25] Hart RA, Gundle KR, Pro SL, et al. Lumbar stiffness disability index: pilot testing of consistency, reliability, and validity[J]. Spine J, 2013, 13(2):157-161.

[26] Daniels AH, Smith JS, Hiratzka J, et al. Functional limitations due to lumbar stiffness in adults with and without spinal deformity[J]. Spine, 2015, 40(20):1599-1604.

[27] Sciubba DM, Scheer JK, Smith JS, et al. Which daily functions are most affected by stiffness following total lumbar fusion: comparison of upper thoracic and thoracolumbar proximal endpoints[J]. Spine, 2015, 40(17):1338-1344.

[28] Abul-Kasim K, Ohlin A. Evaluation of implant loosening following segmental pedicle screw fixation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a 2 year follow-up with low-dose CT[J]. Scoliosis, 2014, 9:13.

[29] Cho W, Mason JR, Smith JS, et al. Failure of lumbopelvic fixation after long construct fusions in patients with adult spinal deformity: clinical and radiographic risk factors: clinical article[J]. J Neurosurg Spine, 2013, 19(4):445-453.

[30] Berven SH. Clinical incidence of PJK/ASD in adult deformity surgery: a comparison of rigid fxation and semirigid fxationrigid[J]. Spine, 2016, 41(Suppl 7):S35-36.

[31] Kim HJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Patients with proximal junctional kyphosis requiring revision surgery have higher postoperative lumbar lordosis and larger sagittal balance corrections[J]. Spine, 2014, 39(9):E576-580.

[32] Rothenfluh DA, Mueller DA, Rothenfluh E, et al. Pelvic incidence-lumbar lordosis mismatch predisposes to adjacent segment disease after lumbar spinal fusion[J]. Eur Spine J, 2015, 24(6):1251-1258.

( 本文编辑:王萌 )

Correlation between pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis mismatch after surgery for degenerative scoliosis and clinical outcomes

SUN Xiang-yao, ZHANG Xi-nuo, HAI Yong. Department of Orthopedics, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, 100020, China Corresponding author: Hai Yong, Email: spinesurgeon@163.com

ObjectiveTo explore the correlation between pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis ( PI-LL ) mismatch after the surgery for adult degenerative scoliosis ( ADS ) and correction of scoliosis, quality of life and failure of internal fixation.MethodsThe clinical data of 69 patients with ADS who underwent long posteriorinstrumentation and fusion from January 2010 to January 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. There were 21 males and 48 females, whose mean age was ( 63.7 ± 4.7 ) years old. They were followed up for an average period of ( 3.2 ± 0.7 ) years. The patients were divided into 3 groups: group A ( PI-LL≤10° ), group B ( 10° < PI-LL≤20° ) and group C ( PI-LL > 20° ). The radiographic sagittal parameters were measured before and after the operation and at the latest follow-up. The patients’ quality of life was evaluated after the operation and at the latest follow-up according to the Japanese Orthopaedic Association ( JOA ) score, Oswestry disability index ( ODI ), visual analogue scale ( VAS ) and lumbar stiffness disability index ( LSDI ), and these parameters were statistically analyzed. Then, PI-LL could be worked out. Univariate linear regression equation was performed to investigate the relative infuence of postoperative PI-LL on radiographic parameters and clinical outcomes.ResultsIn group A, the preoperative Cobb’s angle of scoliosis, preoperative PI-LL, preoperative ODI, preoperative JOA, preoperative VAS, Cobb’s angle of scoliosis at the latest follow-up, immediate postoperative PI-LL, ODI at the latest follow-up, JOA at the latest follow-up, VAS at the latest follow-up and LSDI at the latest follow-up were ( 19.4 ± 2.9 ) °, ( 35.8 ± 5.2 ) °, 63.5 ± 2.7, 5.4 ± 1.2, 7.1 ± 1.3, ( 4.4 ± 2.7 ) °, ( 5.1 ± 3.0 ) °, 26.7 ± 4.1, 2.7 ± 1.3, 3.0 ± 1.2 and 3.2 ± 1.0 respectively. In group B, the preoperative Cobb’s angle of scoliosis, preoperative PI-LL, preoperative ODI, preoperative JOA, preoperative VAS, Cobb’s angle of scoliosis at the latest follow-up, immediate postoperative PI-LL, ODI at the latest follow-up, JOA at the latest followup, VAS at the latest follow-up and LSDI at the latest follow-up were ( 20.1 ± 2.6 ) °, ( 36.6 ± 4.0 ) °, 62.9 ± 3.0, 5.6 ± 1.2, 6.8 ± 1.4, ( 3.7 ± 1.3 ) °, ( 17.6 ± 2.0 ) °, 17.5 ± 3.9, 3.2 ± 1.2, 3.1 ± 0.9 and 1.5 ± 1.2 respectively. In group C, the preoperative Cobb’s angle of scoliosis, preoperative PI-LL, preoperative ODI, preoperative JOA, preoperative VAS, Cobb’s angle of scoliosis at the latest follow-up, immediate postoperative PI-LL, ODI at the latest follow-up, JOA at the latest follow-up, VAS at the latest follow-up and LSDI at the latest follow-up were ( 21.3 ± 2.8 ) °, ( 35.3 ± 4.1 )°, 62.4 ± 2.8, 5.8 ± 1.3, 6.7 ± 1.3, ( 4.5 ± 0.8 ) °, ( 25.9 ± 2.9 ) °, 32.7 ± 5.2, 3.1 ± 1.6, 3.1 ± 0.8 and 0.8 ± 0.8 respectively. The postoperative Cobb’s angle of scoliosis, PI-LL, JOA, ODI and VAS were signifcantly improved, compared with the preoperative data ( P < 0.001 ). There were statistically signifcant differences in immediate postoperative PI-LL among the 3 groups ( P < 0.001 ). However, there were no statistically signifcant differences in other radiographic parameters among the 3 groups. There were statistically signifcant differences in ODI and LSDI at the latest followup among the 3 groups ( P < 0.001 ). However, there were no statistically signifcant differences in other life quality indexes. The internal fxation failure rate was lower in group B than the other groups ( P = 0.005 ). There were no statistically signifcant differences in the reoperation rate ( P = 0.620 ). Curve estimation showed that stroke equation ftted the relationship between postoperative PI-LL and Cobb’s angle ( R2= 0.416, P < 0.001 ). Cubic equation ftted the relationship between postoperative PI-LL and ODI ( R2= 0.370, P < 0.001 ) or LSDI at the latest follow-up ( R2= 0.720, P < 0.001 ). However, there was a low correlation between postoperative PI-LL and other indexes ( P < 0.05 ). Conclusions The optimal PI-LL may be between 10° and 20° in ADS patients after long posterior instrumentation and fusion for better clinical outcomes and lower complication rates related to postoperative internal fixation. The overcorrection of LL will result in lower PI-LL, and then may lead to more serious postoperative lumbar stiffness.

Scoliosis; Pelvic parameter; Quality of life; Spinal fusion

10.3969/j.issn.2095-252X.2017.01.005

R682, R687.3

100020 北京,首都医科大学附属北京朝阳医院骨科

海涌,Email: spinesurgeon@163.com

2016-09-21 )