Uncoupling protein 2 in the glial response to stress: implications for neuroprotection

2016-12-01DanielHassColinBarnstableDepartmentofNeuralandBehavioralSciencesThePennsylvaniaStateUniversityCollegeofMedicineHersheyPAUSA

Daniel T. Hass, Colin J. BarnstableDepartment of Neural and Behavioral Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA

INVITED REVIEW

Uncoupling protein 2 in the glial response to stress: implications for neuroprotection

Daniel T. Hass, Colin J. Barnstable*

Department of Neural and Behavioral Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA

How to cite this article: Hass DT, Barnstable CJ (2016) Uncoupling protein 2 in the glial response to stress∶ implications for neuroprotection. Neural Regen Res 11(8)∶1197-1200.

orcid:

0000-0002-7011-4068

(Colin J. Barnstable)

Accepted: 2016-08-10

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are free radicals thought to mediate the neurotoxic effects of several neurodegenerative disorders. In the central nervous system, ROS can also trigger a phenotypic switch in both astrocytes and microglia that further aggravates neurodegeneration, termed reactive gliosis. Negative regulators of ROS, such as mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) are neuroprotective factors that decrease neuron loss in models of stroke, epilepsy, and parkinsonism. However, it is unclear whether UCP2 acts purely to prevent ROS production, or also to prevent gliosis. In this review article, we discuss published evidence supporting the hypothesis that UCP2 is a neuroprotective factor both through its direct effects in decreasing mitochondrial ROS and through its effects in astrocytes and microglia. A major effect of UCP2 activation in glia is a change in the spectrum of secreted cytokines towards a more anti-inflammatory spectrum. There are multiple mechanisms that can control the level or activity of UCP2, including a variety of metabolites and microRNAs. Understanding these mechanisms will be key to exploitingthe protective effects of UCP2 in therapies for multiple neurodegenerative conditions.

neuroprotection; astrocytes; microglia; reactive oxygen species; oxidative stress; mitochondrial uncoupling proteins; cytokines; neurodegeneration

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are free radicals that can damage DNA, lipids, and proteins. In neurons, elevations in ROS in neurons are associated with cell death and degeneration, while increases in glial ROS can stimulate a phenotypic change known as reactive gliosis, characterized by several alterations in homeostatic function (Sofroniew, 2009; Choi et al., 2012). While in some circumstances gliosis creates a supportive environment in the central nervous system (CNS), during neurodegeneration it more frequently inhibits neuronal survival and regeneration (Sofroniew, 2009; Tang and Le, 2016). ROS-induced cellular damage and gliosis are both pathogenic mechanisms implicated in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and stroke (Sofroniew, 2009; Tang and Le, 2016).

Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) is a solute carrier protein in the inner mitochondrial membrane that regulates proton leak and consequently the production of mitochondrial ROS (Krauss et al., 2005). UCP2 activity is protective against ROS-induced cell death in the CNS (Mattiasson et al., 2003; Barnstable et al., 2016). While UCP2 can be protective by acting directly in neurons, the main objective of this article is to provide support for the hypothesis that a component of UCP2’s neuroprotective effect originates in glia, and works by reducing the inflammatory response of glia to oxidative stress. We initiated a Medline search for “UCP2 AND (astrocytes OR microglia)”, and found several key publications that support this hypothesis. We detail these findings in Table 1 and below.

ROS and Disorders of the CNS

ROS, such as O-2, H2O2, HO-2are anobligatory result of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and are normally detoxified by endogenous antioxidant proteins such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione. When ROS levels exceed the protective buffer of these antioxidant defenses, cells become oxidatively stressed. Persistent oxidative stress can cause cell dysfunction and eventually death. While oxidative stress in the CNS may directly cause neuronal death, it also triggers several morphological and functional changes in astrocytes and microglia in a process known as reactive gliosis (Choi et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2014). While reactive gliosis is frequently supportive of neuronal survival after an acute injury or stroke, persistent glial reactivity is thought to contribute to neuronal death by disrupting the homeostasis of metabolism and cell signaling (Sofroniew, 2009). Although these phenomena are only reactions to an initial insult that causes neurodegeneration, both oxidative stress and reactive gliosis are hallmarks and potential therapeutic targets in several neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, ALS, and stroke (Sofroniew, 2009; Choi et al., 2012; Tang and Le, 2016).

Neuroprotection by Uncoupling

Given the interplay between oxidative stress, reactive gliosis, and neurodegeneration, we propose a therapeutic strategy that protects against neurodegeneration by decreasing ROS levels and preventing pathogenic glial activation. The majority of cellular ROS are produced in mitochondria,and ROS production is higher at greater transmembrane proton gradients (Korshunov et al., 1997). Our approach to decreasing ROS is to utilize the endogenous function of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs). UCPs are proton transporters situated in the inner mitochondrial membrane, and are involved in diminishing the transmembrane proton gradient (Krauss et al., 2005). This activity reduces the drive for ROS production and consequently decreases cell death (Lapp et al., 2014). Mitochondrial uncoupling has been best exhibited as a neuroprotective strategy in studies of uncoupling protein 2 the activity and overexpression of which can dramatically decrease CNS cell death due to oxidative damage in vitro, as well as in mouse models of pilocarpine-induced seizures, middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced stroke, parkinsonism induced by the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced retinal excitotoxicity (Mattiasson et al., 2003; Lapp et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2014; Barnstable et al., 2016). Although UCP2 overexpression in mice is a well-validated strategy for protection against ROS-induced cell death, it is unclear whether this activity is the entire mechanism of UCP2-mediated neuroprotection. While many previous studies have assumed that the primary site of UCP2’s action is within neurons, we propose that mitochondrial uncoupling has an equally important effect on glial cells of the CNS. The studies we review suggest that in addition to its directly effects which protect against ROS-induced cell death, UCP2 is also able to regulate the response of astrocytes and microglia to cellular stress.

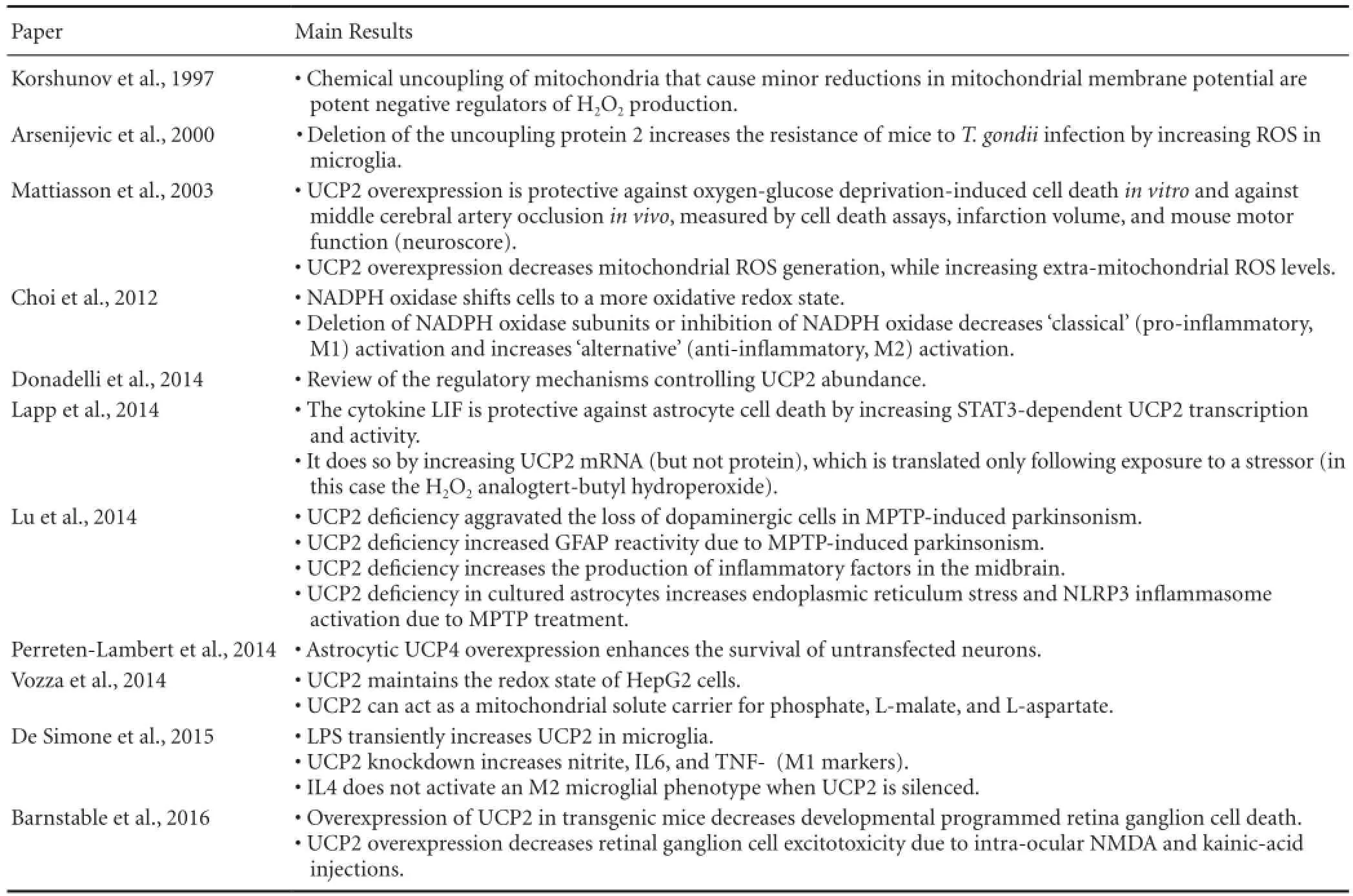

Table 1 Relevant findings of discussed literature

The Effects of UCP2 Activity in Astrocytes

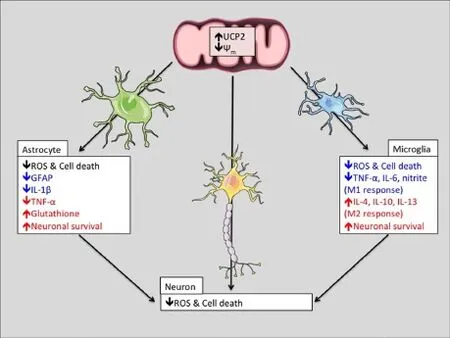

Astrocytes are the most abundant cell type in the CNS. They promote neuronal survival by regulating the levels of neurotransmitter, metabolites, and antioxidants in the extracellular environment (Sofroniew, 2009). In disorders of the CNS, astrocytes can adopt a reactive, pro-inflammatory phenotype, characterized by the upregulation of the intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a reduction in neurotransmitter uptake, metabolic changes, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Sofroniew, 2009). Although at rest UCP2 is found primarily in neurons, our recent data indicate that UCP2 is dynamically regulated and that protein levels in astrocytes rapidly increase in response to cellular stress (Lapp et al., 2014). Findings by Lu et al. suggest that UCP2 plays an important role in glial reactivity. They found that compared to control mice treated with theneurotoxin MPTP, the brains of MPTP-treated UCP2-deficient mice had greater GFAP immunoreactivity and an enhanced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin 1β (IL-1β) (Lu et al., 2014). Similarly, UCP2 deficiency or inhibition in primary astrocyte cultures increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation, IL-1β production, and cell death in response to oxidative stress (Lapp et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2014). These data show that UCP2 can influence the reactive phenotype of stressed astrocytes. In addition to this role, astrocytic UCP2 may also modulate brain oxidative status through its effects on the supply of one of the most potent free-radical scavengers in the CNS, glutathione. Once produced in the brain, ROS can be detoxified either directly by glutathione in astrocytes or from neuron-derived glutathione, which is synthesized using astrocyte-supplied cysteine. UCP2 levels are positively correlated with glutathione content in several tissues (Vozza et al., 2014), suggesting that in the CNS, the activity of astrocytic UCP2 may be important for the preservation of other endogenous antioxidant systems. Functional evidence supporting the hypothesis that mitochondrial uncoupling in astrocytes increases neuronal survival comes from recent studies of the other brain uncoupling proteins. When overexpressed in primary astrocytes, the UCP family members UCP4 and UCP5 decrease basal H2O2release and increase the survival of untransfected neuronal co-cultures (Perreten Lambert et al., 2014). This neuroprotective effect of other uncoupling proteins in glia strongly implies that increases in astrocytic uncoupling proteins, such as UCP2, will similarly increase neuronal survival (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Scheme of hypothetical changes to the function of neurons, astrocytes, and microglia due to uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) activity.

The Effects of UCP2 Activity in Microglia

Microglia are the resident immune cells of the CNS that scavenge the neural environment in order to sense infection or damage. In response to various stimuli, microglia can adopt cytotoxic (M1), or protective (M2) phenotypes. Stimulation of microglia by factors such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and ROS can induce an M1 state characterized by phagocytic activity, the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, nitric oxide, TNF-α, and the generation of ROS (Choi et al., 2012; Tang and Le, 2016). Alternatively, anti-inflammatory signals such as IL-4 can bias microglia towards an M2 state, characterized by the secretion of other anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-13 (Choi et al., 2012; Tang and Le, 2016). In many neurodegenerative disorders, microglia are persistently activated in the M1 state, which may either be the cause or consequence of high ROS levels (Choi et al., 2012). UCP2 is expressed in microglia and dynamically modulates the production of ROS in response to an infection, suggesting that it may also control microglial activation. This is best exemplified in UCP2 deficient mice, which are immune to toxoplasmosis infection due the ability of their microglia to generate excessive levels of ROS and IL-1β (Arsenijevic et al., 2000). More recent findings also support the hypothesis that UCP2 controls the activation state of microglia. De Simone et al. (2015) demonstrated that microglial UCP2 deficiency increases the LPS-stimulated secretion of the M1 markers nitrite, TNF-α, and IL-6. The same study also found a correlative relationship between levels of IL-4, which stimulates an M2 phenotype and the transcription of UCP2 (De Simone et al., 2015). Due to the causal relationship between microglial ROS and cellular phenotype (Choi et al., 2012; De Simone et al., 2015), increases in UCP2 activity may prejudice microglia towards an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, which may be neuroprotective in disorders characterized by persistent glial reactivity (Figure 1). However, it is important to note that the activity of UCP2 is only beneficial under certain circumstances, and based on the literature presented above, UCP2 overexpression could handicap the innate immune response to brain infection. Together, the known effects of UCP2 on astrocytic and microglial phenotypes denote asignificant role for UCP2 in the glial response to cellular stress, and imply that increases in UCP2 will be neuroprotective by reversing the secretion of inflammatory factors and increasing or preserving the supply of endogenous antioxidants.

韩愈在他的《伯夷颂》中,盛赞伯夷“特立独行”“信道笃而自知明”。伯夷的事有些争议,且不提他。但李斯的事,还是值得一说的。秦王朝建立以后,丞相王绾提出以分封制治国,没有人提出疑义,独李斯区区一个廷尉,敢当众站出来反对,并提出了一个新的制度,即郡县制。重要的是,他舌战群儒,最终使得秦始皇采纳了他的意见。郡县制奠定了中国两千多年封建社会政治制度的基本格局,也为现代的行政区划分提供了重要的历史参考。

Mitochondrial Uncoupling is Highly Regulated

In order to exploit the protective effect of UCP2 in glia or any other cell type, we must understand the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational mechanisms that control its activity and protein levels. Astrocytic UCP2 is transcriptionally regulated by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), sirtuins, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α/β (PGC1α/β), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), thyroid hormone receptors, and SMAD4 (Donadelli et al., 2014; Lapp et al., 2014). These factors are each endpoints of multiple cellular pathways that respond to a wide range of stimuli, implying that UCP2 transcription is a response to many different cellular conditions. However, as several groups have demonstrated, UCP2 transcription does not always correlate with protein expression (Lapp et al., 2014). Instead, UCP2 is regulated post-transcriptionally by several factors, including LPS, superoxide, and glutamine (Donadelli et al., 2014). These factors are thought to work through a number of ways. One is inhibition of translation through a constitutively active upstream open reading frame (uORF) in exon 2 of the UCP2 transcript (Donadelli et al., 2014). Specific microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins can also regulate UCP2 mRNA stability. For example, transcript degradation by mmu-miR-30e or has-miR-15a in kidney epithelium and colorectal cancer cells, translational inhibition mmu-miR-133a in muscle tissue, and translational enhancement by the RNA-binding protein hnRNP-K in heart tissue have all been described (Donadelli et al., 2014). The cell-type specific nature of microRNAs and other factors mentioned above may eventually allow for microRNA-based therapeutics, which can inhibit the negative regulation of UCP2 in select cell types such as microglia or astrocytes. In addition to the numerous factors that control UCP2 mRNA and protein levels, the proton transport activity of UCP2 is also dynamically regulated. The proton conductance of UCP2 is stimulated by coenzyme Q, fatty acids, and superoxides in the mitochondrial matrix, and inhibited by glutathione via a reversible covalent modification (Donadelli et al., 2014). The complexity of these regulatory mechanisms implies multiple points of intervention to manipulate UCP2 levels, especially through non-invasive molecules such as glutathione, fatty acids, glutamine, and coenzyme Q. The modulation of these molecules in the diet may be a simple way by which to increase uncoupling activity and potentially stimulate the protective effects of UCP2 in the CNS.

Conclusions

Current therapeutic efforts directed at reducing oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders have yet to be successful in clinical trials, implying the need for more potent regulators of ROS levels. Despite substantial evidence implying that the modulation of oxidative stress by UCP2 will be protective across a wide spectrum of disorders, UCP2-based therapeutics have yet to be developed for humans. Given the many ways in which endogenous regulatory machinery can regulate the levels and activity of UCP2, we believe there are many opportunities to design therapeutic agents that can manipulate this machinery. Since the UCP2 plays a critical role in the response of astrocytes and microglia to damage, we propose that increasing glial UCP2 activity may be therapeutic by decreasing the secretion of inflammatory factors and increasing or preserving the supply of endogenous antioxidants to increase neuronal survival (Figure 1).

Author contributions: DTH and CJB each contributed to the preparation and editing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

Arsenijevic D, Onuma H, Pecqueur C, Raimbault S, Manning BS, Miroux B, Couplan E, Alves-Guerra MC, Goubern M, Surwit R, Bouillaud F, Richard D, Collins S, Ricquier D (2000) Disruption of the uncoupling protein-2 gene in mice reveals a role in immunity and reactive oxygen species production. Nat Genet 26:435-439.

Barnstable CJ, Reddy R, Li H, Horvath TL (2016) Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) regulates retinal ganglion cell number and survival. J Mol Neurosci 58:461-469.

Choi SH, Aid S, Kim HW, Jackson SH, Bosetti F (2012) Inhibition of NADPH oxidase promotes alternative and anti-inflammatory microglial activation during neuroinflammation. J Neurochem 120:292-301.

De Simone R, Ajmone-Cat MA, Pandolfi M, Bernardo A, De Nuccio C, Minghetti L, Visentin S (2015) The mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 is a master regulator of both M1 and M2 microglial responses. J Neurochem 135:147-156.

Donadelli M, Dando I, Fiorini C, Palmieri M (2014) UCP2, a mitochondrial protein regulated at multiple levels. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:1171-1190.

Korshunov SS, Skulachev VP, Starkov AA (1997) High protonic potential actuates a mechanism of production of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria. FEBS Lett 416:15-18.

Krauss S, Zhang CY, Lowell BB (2005) The mitochondrial uncoupling-protein homologues. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:248-261.

Lapp DW, Zhang SS, Barnstable CJ (2014) Stat3 mediates LIF-induced protection of astrocytes against toxic ROS by upregulating the UPC2 mRNA pool. Glia 62:159-170.

Lu M, Sun XL, Qiao C, Liu Y, Ding JH, Hu G (2014) Uncoupling protein 2 deficiency aggravates astrocytic endoplasmic reticulum stress and nod-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activation. Neurobiol Aging 35:421-430.

Mattiasson G, Shamloo M, Gido G, Mathi K, Tomasevic G, Yi S, Warden CH, Castilho RF, Melcher T, Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Nikolich K, Wieloch T (2003) Uncoupling protein-2 prevents neuronal death and diminishes brain dysfunction after stroke and brain trauma. Nat Med 9:1062-1068.

Perreten Lambert H, Zenger M, Azarias G, Chatton JY, Magistretti PJ, Lengacher S (2014) Control of mitochondrial pH by uncoupling protein 4 in astrocytes promotes neuronal survival. J Biol Chem 289:31014-31028.

Sofroniew MV (2009) Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci 32:638-647.

Tang Y, Le W (2016) Differential roles of M1 and M2 microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurobiol 53:1181-1194.

Vozza A, Parisi G, De Leonardis F, Lasorsa FM, Castegna A, Amorese D, Marmo R, Calcagnile VM, Palmieri L, Ricquier D, Paradies E, Scarcia P, Palmieri F, Bouillaud F, Fiermonte G (2014) UCP2 transports C4 metabolites out of mitochondria, regulating glucose and glutamine oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:960-965.

10.4103/1673-5374.189159

*Correspondence to: Colin J. Barnstable, D.Phil., cbarnstable@psu.edu.

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Secondary parkinsonism induced by hydrocephalus after subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage

- Volume transmission and receptor-receptor interactions in heteroreceptor complexes: understanding the role of new concepts for brain communication

- Selective neuronal PTEN deletion: can we take the brakes off of growth without losing control?

- TRPV1 may increase the effectiveness of estrogen therapy on neuroprotection and neuroregeneration

- Tamoxifen: an FDA approved drug with neuroprotective effects for spinal cord injury recovery

- Automatic counting of microglial cell activation and its applications