循环肿瘤DNA在临床应用中的研究进展

2016-11-18李妙竹林健振赵海涛

李妙竹,林健振,赵海涛

1美国杜克大学人群衰老健康研究所,北卡罗来纳州 277052 中国医学科学院 北京协和医学院 北京协和医院肝脏外科,北京 100730

·综 述·

循环肿瘤DNA在临床应用中的研究进展

李妙竹1,林健振2,赵海涛2

1美国杜克大学人群衰老健康研究所,北卡罗来纳州 277052中国医学科学院 北京协和医学院 北京协和医院肝脏外科,北京 100730

分子诊断检测肿瘤相关突变正越来越多的被应用于癌症患者的临床护理和管理。含有肿瘤突变的循环肿瘤DNA(ctDNA)可以在疾病进程中被多次采集,是一种简单有效的非侵入性“液体活检”技术。作为一种潜在的肿瘤标志物,ctDNA检测有望在肿瘤治疗中对疾病预后判断、动态监测、用药指导和异质评估发挥重要的临床应用价值。但ctDNA检测技术需要进一步规范检测流程,提高检测的可重复性和准确性,才能更好服务于精准医疗。

循环肿瘤DNA;肿瘤;基因突变;动态监测;异质性

ActaAcadMedSin,2016,38(5):594-600

癌症是世界范围发病率和死亡率最高的疾病之一,2012年全球新发病例1410万例,死亡820万例。预计到2035年,全球癌症总数将超过2400万例,1460万人死于癌症[1]。癌症发生的过程中存在各种基因突变和结构改变,检测肿瘤组织中存在的突变类型有助于了解肿瘤的发病机制,如果将肿瘤特异性分子标记用于诊断、评估和预测,可以获得良好的治疗效果[2]。MIT Technology Review 公布的2015年度十大突破技术之一——液体活检,以其简单易行、灵敏特异、无创或微创,给传统癌症治疗带来了颠覆性变革。其中,外周血中游离的核酸小片段DNA,循环肿瘤DNA (circulating tumor DNA,ctDNA)作为一种潜在的肿瘤标志物近来备受关注。

ctDNA的发现史和生物学特性

1948年,Mandel等[3]从正常人血液中检测到游离的DNA 片段(cell-free DNA,cfDNA),但他们的先驱工作并未得到足够重视。1977年,Leon等[4]发现肿瘤患者体内cfDNA含量明显高于健康个体,而晚期肿瘤患者含量更高。随着研究不断深入,1989年,Stroun[5]发现在肿瘤患者的血浆和血清cfDNA中存在与肿瘤基因改变相同的DNA片段,科学家将其命名为ctDNA[6]。血液中循环DNA主要来源于细胞的凋亡、坏死和分泌[7],通常cfDNA会被实时清除并保持极低含量,每毫升血浆中只有大约十几纳克(ng)的cfDNA。例如常规科研实践采集10 ml的血液里,有约2万细胞的cfDNA。但在肿瘤组织中细胞代谢旺盛导致大量凋亡和坏死,增加释放游离核酸cfDNA。因此,碎片化、低含量的ctDNA有以下独有特征:(1)片段短小,约150~200 bp[8];(2)半衰期短:15 min至数小时(平均约2 h);(3)ctDNA占cfDNA比例0.01%~90.00%不等;(4)ctDNA水平与肿瘤类型、肿瘤负荷和肿瘤进展等相关[9]。

ctDNA的检测技术

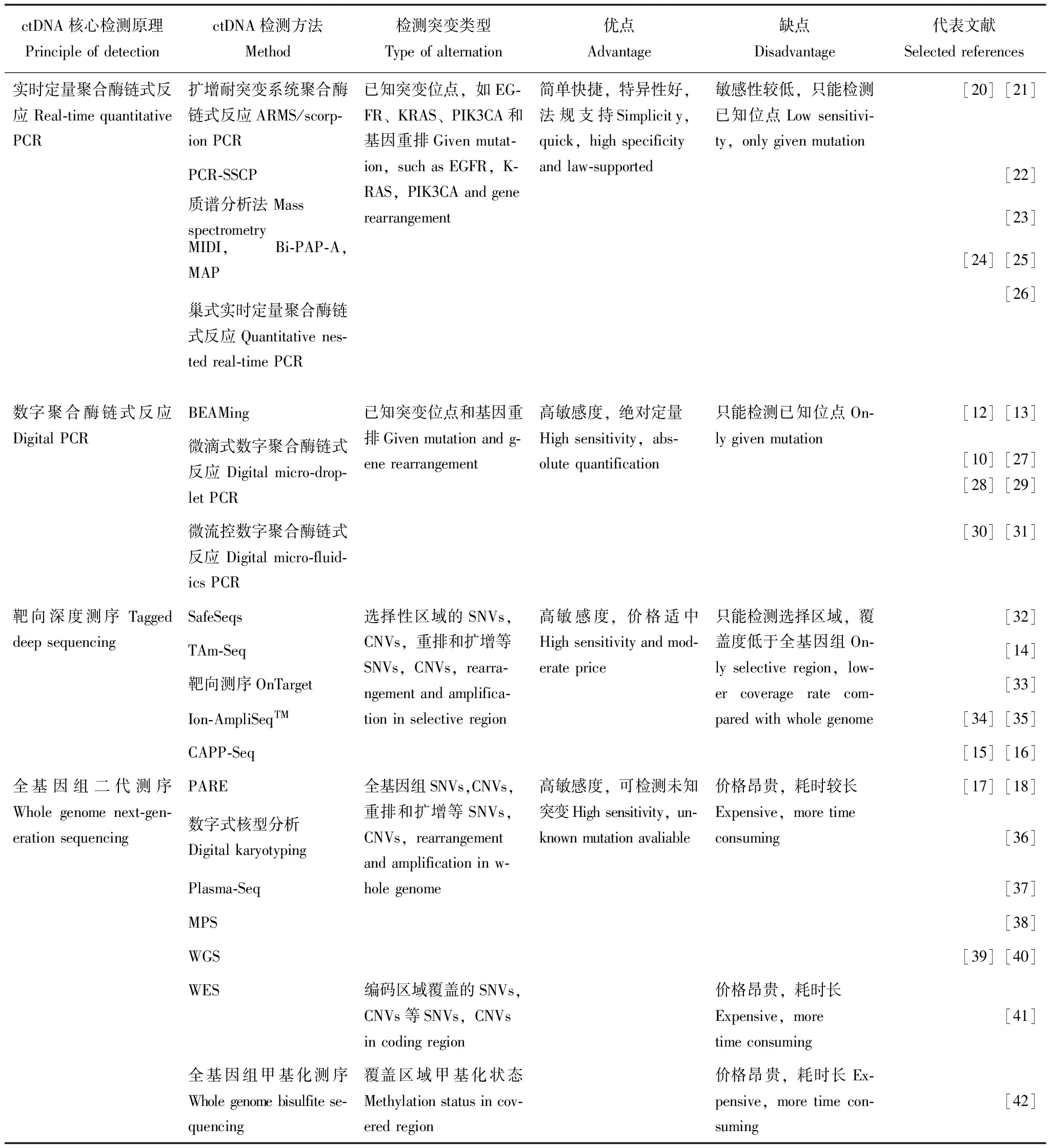

目前既可以对ctDNA浓度进行定量分析,也可以对ctDNA进行定性分析,包括检测基因突变、缺失、插入、融合、重排、拷贝数变异、甲基化、微卫星不稳定(microsatellite instability,MSI)和杂合性缺失(loss of heterozygosity,LOH)等。定量和定性两种方法均可以反映肿瘤的存在和严重程度。常见ctDNA突变和结构变化的检测方法大致分两种,一种以聚合酶链式反应(polymerase chain reaction,PCR)为基础扩增,另一种以新一代测序(next generation sequencing,NGS)为基础检测。PCR相关技术检测精度高,灵敏度也较高,但获得信息较为局限,可以用于微量核酸检测;NGS相关技术检测速度快,覆盖广,可以实现全基因组高通量检测,但假阳性比率有待进一步验证。科学家们在此基础上开发了以下一系列灵敏特异的ctDNA检测方法,包括:定量PCR(quantitative polymerase chain reaction,qPCR)、微滴数字式PCR(droplet digital PCR,ddPCR)[10],数字PCR结合流式技术(beads,emulsion,amplification,magnetics,BEAMing)[11- 13]、标记扩增深度测序法(Tagged-amplicon deep sequencing,TAm-seq)[14]、肿瘤个体化分析深度测序法(cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing,CAPP-Seq)[15- 16]、全基因组测序[17- 18]、全外显子测序,全基因组甲基化测序等[19]。表1列举了目前一些常见ctDNA的检测方法对比和应用。

ctDNA检测的临床应用

传统癌症治疗中,医生通过手术或穿刺针取出肿瘤样本,在显微镜下观察病理组织切片并进行遗传学分析,做出诊断指导治疗。这种方法具有侵入性和一定风险,而且比较昂贵。对于肿瘤演化产生的异质性和抗药性,以及转移期患者体内存在多个肿瘤病灶,单次原位活检存在很大局限。ctDNA检测则具有以下多方面优势:(1)低创无创,最大程度减少患者痛苦;(2)灵敏特异,检测准确率高;(3)取样容易,多次采集实时监控;(4)全面广泛,适合肿瘤转移扩散的患者。因此,在临床医学上有多方面应用。

早期诊断 采用ctDNA检测技术对早期患者的诊断依然处于科研探索阶段,特别对Ⅰ期患者的检测敏感性在50%左右[15,43]。Beaver 等[28]采用灵敏的ddPCR检测,对29例早期(Ⅰ~Ⅲ期)乳腺癌患者在术前同时对组织和血浆热点突变PIK3CA进行检测,15例在肿瘤组织中、14例在循环血液中检测到突变。ctDNA检测敏感性93.3%,特异性100%。术前10例血浆检测到ctDNA的患者中,5例术后血浆中依然能检测到微量PIK3CA突变。对于早期患者,检测血液ctDNA做诊断目前处于科研探索阶段,可以作为一些热点突变的初筛和肿瘤组织检测的补充。

术后判断 通过检测ctDNA水平评估手术效果,判断肿瘤是否已经切除干净。手术和化疗可以明显影响ctDNA的含量,ctDNA浓度与患者生存率显著相关,浓度越高患者生存率越低[13]。Sausen等[44]收集了101例Ⅱ期胰腺癌患者的肿瘤标本和血液样本,进行全外显子组测序。结果发现,在接受肿瘤切除的早期胰腺癌患者中,如果检测不到ctDNA,说明手术成功预后较好;如果检测到ctDNA,可能有残留组织预后较差,更容易复发,两组患者存在显著差异。同时,与标准CT影像学相比,ctDNA可以提前6.5个月检测到肿瘤复发。

表 1 常见血液循环肿瘤DNA检测方法对比

PCR:聚合酶链式反应;ARMS:扩增耐突变系统;SSCP:单链构象多态性;Bi-PAP-A:双向焦磷酸解活性聚合等位基因特异性扩增;MAP:MIDI活化的焦磷酸盐溶解;BEAMing:小珠、乳浊液、扩增、磁性;SafeSeq:安全测序系统;Tam-Seq:靶向扩增子深度测序;CAPP-Seq:肿瘤的个体化深度分析;PARE:重排末端的个体化分析;MPS:大量平行测序;WGS:全基因组测序;WES:全外显子组测序;KRAS:Kirsten鼠肉瘤病毒癌基因同源;EGFR:表皮生长因子受体;PIK3CA:磷脂酰环己六醇- 4,5-磷酸氢盐- 3激酶的α催化亚基;SNVs:单核苷酸多态性;CNVs:拷贝数变异

PCR:polymerase chain reaction;ARMS:amplified refractory mutation system;SSCP:single-strand conformation polymorphism;Bi-PAP-A:bidirectional pyrophosphorolysis-activated polymerization allele-specific amplification;MAP:MIDI-Activated pyrophosphorolysis;BEAMing:beads,emulsion,amplification,and magnetics;SafeSeq:safe sequencing system;Tam-Seq:tagged amplicon deep sequencing;CAPP-Seq:cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing;PARE:personalized analysis of rearranged ends;MPS:massively parallel sequencing;WGS:whole-genome sequencing;WES:whole-exome sequencing;KRAS:Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog;EGFR:epidermal growth factor receptor;PIK3CA:phosphatidylinositol- 4,5-biphosphate 3-kinase,catalytic subunit alpha;SNVs:single-nucleotide variants;CNVs:copy number variations

英国癌症研究所肿瘤分子研究团队Garcia-Murillas等[45]研究了55例早期乳腺癌患者手术前后血液ctDNA的变化情况,患者均先后接受手术和化疗。利用ddPCR和原发性肿瘤体细胞突变标识,研究人员发现治疗后血液样本ctDNA与乳腺癌高风险复发相关。在15例复发患者中,12例(80%)在变异追踪中检测到ctDNA;而对于没有出现复发的患者,有96%在突变追踪都未能发现ctDNA。治疗后血液ctDNA呈阳性的患者癌症复发概率比ctDNA呈阴性的患者高12倍。血液中的ctDNA可提前7.9个月发现乳腺癌复发。

动态监测 以ctDNA作为肿瘤标志物,多次取样定性定量检测肿瘤负荷,监控疾病复发;同时还可以追踪药物对患者肿瘤的响应程度,通过药物疗效信息及时采取调整或治疗措施。当靶向药有效时,ctDNA中药物敏感的肿瘤特异突变减少,一旦产生耐药,ctDNA中耐药突变增加。目前在肝癌[46]、乳腺癌[41,45]、胰腺癌[47]、结直肠癌[43]、非小细胞肺癌[41]等多种癌症中都有报道。最经典的案例之一是来自剑桥大学的研究人员对1例乳腺癌患者长达3年的追踪研究。Murtaza等[48]对1例肿瘤扩散至身体其他部位的乳腺癌患者,分别采集肿瘤样本和血液样本,并仔细对比了同一时间点采集的ctDNA和活体组织切片。结果显示,血液样本中的ctDNA与活体肿瘤样本测序结果相匹配,反映了当肿瘤进展和响应药物治疗时的相同模式和遗传变化。结合患者采取的治疗方案,治疗过程中做了一系列血浆ctDNA突变分析:(1)深度测序观察PIK3CA突变动态变化,PIK3CA突变可能与他莫昔芬和曲妥珠单抗使用过程中瘤体大小有关;(2)深度测序观察ERBB4突变动态变化,ERBB4可能是导致拉帕替尼耐药性突变位点。说明ctDNA可以实时监控疾病情况,辅助调整治疗方案。

用药指导 通过对ctDNA中肿瘤特异的突变检测,能够有效反映患者对治疗的响应。取治疗前后的血浆样本,对ctDNA测序鉴定药物治疗过程中产生的耐药突变。Newman 等[15]采用新研发的高敏感ctDNA检测方法CAPP-Seq,分别对早、晚期非小细胞肺癌(non-small cell lung cancer,NSCLC)患者进行检测。结果显示,1例Ⅵ期NSCLC患者在接受3个月化疗后通过影像学检查发现肿瘤缩小,同时ctDNA水平有所下降。但8个月后,患者ctDNA水平呈现升高,提示隐匿微小肿瘤病灶出现进展。通过对ctDNA检测发现患者存在ALK融合基因,随即使用 ALK融合基因靶向药物克唑替尼进行治疗,患者病情得到很大改善,ctDNA水平也再次降低。在NSCLC治疗中,检测表皮生长因子受体(epithelial growth factor receptor,EGFR)对决定用药治疗方案非常重要。通过血浆ctDNA检测可以发现当新的T790M位点突变产生后,患者出现对吉非替尼[41]、厄洛替尼或厄洛替尼和帕妥珠单抗联用药物耐受[49]。一旦出现T790M位点突变会出现EGFR-酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor,EGFR-TKI)抵抗[50],需要调整治疗方案,尝试新一代不可逆EGFR-TKI抑制剂、化疗等其他临床选择[51]。

出现KRAS和BRAF基因突变是转移性结直肠癌三线治疗原发抵抗的主要原因,Diaz等[52]检测了28例接受帕尼单抗治疗结肠癌患者的ctDNA,发现只有40%的野生型KRAS患者对EGFR阻断治疗敏感,原发性及治疗过程中获得性KRAS突变是出现EGFR阻断治疗不敏感的原因,联合治疗可能是更长期缓解的最有效方法[53]。对晚期结肠癌血液ctDNA检测可以有效指导临床用药[54]。

异质评估 癌症在患者体内不断分裂产生新的基因变异,进化发生药物抗性使癌细胞继续存活并增殖。ctDNA可以作为有效标记物,评估肿瘤异质性。英国癌症研究院的Garcia-Murillas等[45]对55例以手术和化疗为根治性治疗的早期乳腺癌患者进行ctDNA追踪,结果发现,在不同个体中,检测到ctDNA的突变可能只出现在原发瘤或只出现在转移瘤,也可能同时出现于两类肿瘤组织。

Murtaza等[48]用贝叶斯聚类方法PyClone对已发现的207个功能性突变进行聚类,探索出以下3组主要肿瘤异种:(1)突变主要发生在癌症进化早期;(2)突变在所有转移性肿瘤样本中存在高丰度,但在原发肿瘤中不易发现;(3)突变具有相对多样性,分散在不同时期的肿瘤活检样本中。血液样本中ctDNA含有的随机突变反映了肿瘤单克隆群的不同大小和活性,揭示出肿瘤异质性变化的顺序。

其他应用 除了研究血液中的ctDNA,科学家也在积极探索脑脊液ctDNA作为脑肿瘤液体活检标志物克服血脑屏障影响[55],另有最新报道肺癌患者唾液中ctDNA呈现与血液ctDNA相近的检测效果[56]。美国Trovagene公司则坚持多年钻研样本源丰富的尿液ctDNA标记物。ctDNA检测目前已获得一些临床和相关机构认可,欧盟和中国先后于2014、2015年批准阿斯利康易瑞沙(Iressa)血液ctDNA伴随诊断,用于筛查肿瘤组织不可评估的患者人群[57]。

结 语

尽管潜力巨大,目前ctDNA还无法成为临床上的主要诊疗手段,原因如下:(1)早期癌症ctDNA检测难度大[58]。ctDNA检测技术CAPP-Seq可以实现1万个血液DNA检测1个肿瘤DNA,但即使采用超敏感的CAPP-Seq,ctDNA在Ⅱ~Ⅳ期的NSCLC患者中检测敏感性100%,而Ⅰ期NSCLC中敏感性仅为50%[15]。与之类似,在近10种640例癌症患者中的研究也报道,47%的Ⅰ期癌症患者、55%的Ⅱ期癌症患者、69%的Ⅲ期癌症患者及82%的Ⅳ期癌症患者可检测到血液中的ctDNA[43]。(2)不同肿瘤组织ctDNA的含量差异很大。Bettegowda等[43]研究发现,只有不到50%的髓母细胞瘤、转移性肾癌、前列腺癌或甲状腺癌,以及不到10%的胶质瘤患者可以检测到ctDNA;而在超过75%的晚期胰腺癌、卵巢癌、结直肠癌、膀胱癌、胃癌、乳腺癌、黑色素瘤、肝癌以及头颈癌可以检测到ctDNA。(3)检测结果参差不齐。ctDNA检测需要加强流程规范,包括前期血液处理过程和提取cfDNA方法标准化,提高检测的可重复性。(4)临床成本比较昂贵。特别是更为有效和全面的二代测序技术,ctDNA的检测价格依然有待进一步降低,才可能在临床实践中逐渐普及。

综上,对血液ctDNA进行检测具有低创无创、灵敏特异、实时多次、广泛全面等临床优势,其临床应用包括术后判断、动态监测、用药指导、异质评估等。尽管ctDNA检验技术还尚未成熟,需要尽快建立统一的临床标准,但随着ctDNA检测技术基础实验、临床研究和研发应用在深度广度上的日益拓展,利用敏感特异的无创液体活检监控癌症进展、跟踪抗性突变、及时指导用药方案、将癌症从一种致命疾病转变为一种慢性病、基于每个患者定制模式的精准医疗将不再是遥远的梦想。

[1]Ferlay J,Soerjomataram I,Dikshit R,et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide:sources,methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012[J]. Int J Cancer,2015,136(5):E359- E386.

[2]Bates S. Progress towards personalized medicine[J]. Drug Discov Today,2010,15(3- 4):115- 120.

[3]Mandel P,Metais P. Les acides nucléiques du plasma sanguin chez l’homme[J]. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil,1948,142(3- 4):241- 243.

[4]Leon SA,Shapiro B,Sklaroff DM,et al. Free DNA in the serum of cancer patients and the effect of therapy[J]. Cancer Res,1977,37(3):646- 650.

[5]Stroun M,Anker P,Maurice P,et al. Neoplastic characteristics of the DNA found in the plasma of cancer patients[J]. Oncology,1989,46(5):318- 322.

[6]Haber DA,Velculescu VE. Blood-based analyses of cancer:circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA[J]. Cancer Discov,2014,4(6):650- 661.

[7]Schwarzenbach H,Hoon DS,Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients[J]. Nat Rev Cancer,2011,11(6):426- 437.

[8]Jiang P,Chan CW,Chan KC,et al. Lengthening and shortening of plasma DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2015,112(11):E1317- E1325.

[9]Diaz LJ,Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies:genotyping circulating tumor DNA[J]. J Clin Oncol,2014,32(6):579- 586.

[10]Sacher AG,Paweletz C,Dahlberg SE,et al. Prospective validation of rapid plasma genotyping for the detection of EGFR and KRAS mutations in advanced lung cancer[J]. JAMA Oncol,2016,2(8):1014- 1022.

[11]Li M,Diehl F,Dressman D,et al. BEAMing up for detection and quantification of rare sequence variants[J]. Nat Methods,2006,3(2):95- 97.

[12]Dressman D,Yan H,Traverso G,et al. Transforming single DNA molecules into fluorescent magnetic particles for detection and enumeration of genetic variations[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2003,100(15):8817- 8822.

[13]Diehl F,Schmidt K,Choti MA,et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics[J]. Nat Med,2008,14(9):985- 990.

[14]Forshew T,Murtaza M,Parkinson C,et al. Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA[J]. Sci Transl Med,2012,4(136):136r- 168r.

[15]Newman AM,Bratman SV,To J,et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage[J]. Nat Med,2014,20(5):548- 554.

[16]Newman AM,Lovejoy AF,Klass DM,et al. Integrated digital error suppression for improved detection of circulating tumor DNA[J]. Nat Biotechnol,2016,20(5):548- 554.

[17]Leary RJ,Kinde I,Diehl F,et al. Development of personalized tumor biomarkers using massively parallel sequencing[J]. Sci Transl Med,2010,2(20):14r- 20r.

[18]Leary RJ,Sausen M,Kinde I,et al. Detection of chromosomal alterations in the circulation of cancer patients with whole-genome sequencing[J]. Sci Transl Med,2012,4(162):154r- 162r.

[19]Heitzer E,Ulz P,Geigl JB. Circulating tumor DNA as a liquid biopsy for cancer[J]. Clin Chem,2015,61(1):112- 123.

[20]Board RE,Wardley AM,Dixon JM,et al. Detection of PIK3CA mutations in circulating free DNA in patients with breast cancer[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat,2010,120(2):461- 467.

[21]Spindler KL,Pallisgaard N,Vogelius I,et al. Quantitative cell-free DNA,KRAS,and BRAF mutations in plasma from patients with metastatic colorectal cancer during treatment with cetuximab and irinotecan[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2012,18(4):1177- 1185.

[22]Wang JY,Hsieh JS,Chang MY,et al. Molecular detection of APC,K-ras,and p53 mutations in the serum of colorectal cancer patients as circulating biomarkers[J]. World J Surg,2004,28(7):721- 726.

[23]Perkins G,Yap TA,Pope L,et al. Multi-purpose utility of circulating plasma DNA testing in patients with advanced cancers[J]. PLoS One,2012,7(11):e47020.

[24]Shi J,Liu Q,Sommer SS. Detection of ultrarare somatic mutation in the human TP53 gene by bidirectional pyrophosphorolysis-activated polymerization allele-specific amplification[J]. Hum Mutat,2007,28(2):131- 136.

[25]Chen Z,Feng J,Buzin CH,et al. Analysis of cancer mutation signatures in blood by a novel ultra-sensitive assay:monitoring of therapy or recurrence in non-metastatic breast cancer[J]. PLoS One,2009,4(9):e7220.

[26]Mcbride DJ,Orpana AK,Sotiriou C,et al. Use of cancer-specific genomic rearrangements to quantify disease burden in plasma from patients with solid tumors[J]. Genes Chromosomes Cancer,2010,49(11):1062- 1069.

[27]Pekin D,Skhiri Y,Baret JC,et al. Quantitative and sensitive detection of rare mutations using droplet-based microfluidics[J]. Lab Chip,2011,11(13):2156- 2166.

[28]Beaver JA,Jelovac D,Balukrishna S,et al. Detection of cancer DNA in plasma of patients with early-stage breast cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2014,20(10):2643- 2650.

[29]Higgins MJ,Jelovac D,Barnathan E,et al. Detection of tumor PIK3CA status in metastatic breast cancer using peripheral blood[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2012,18(12):3462- 3469.

[30]Dawson SJ,Tsui DW,Murtaza M,et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer[J]. N Engl J Med,2013,368(13):1199- 1209.

[31]Yung TK,Chan KC,Mok TS,et al. Single-molecule detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in plasma by microfluidics digital PCR in non-small cell lung cancer patients[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2009,15(6):2076- 2084.

[32]Kinde I,Wu J,Papadopoulos N,et al. Detection and quantification of rare mutations with massively parallel sequencing[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2011,108(23):9530- 9535.

[33]Thompson JD,Shibahara G,Rajan S,et al. Winnowing DNA for rare sequences:highly specific sequence and methylation based enrichment[J]. PLoS One,2012,7(2):e31597.

[34]Rothe F,Laes JF,Lambrechts D,et al. Plasma circulating tumor DNA as an alternative to metastatic biopsies for mutational analysis in breast cancer[J]. Ann Oncol,2014,25(10):1959- 1965.

[35]Carreira S,Romanel A,Goodall J,et al. Tumor clone dynamics in lethal prostate cancer[J]. Sci Transl Med,2014,6(254):125r- 254r.

[36]Wang TL,Maierhofer C,Speicher MR,et al. Digital karyotyping[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2002,99(25):16156- 16161.

[37]Heitzer E,Ulz P,Belic J,et al. Tumor-associated copy number changes in the circulation of patients with prostate cancer identified through whole-genome sequencing[J]. Genome Med,2013,5(4):30.

[38]Chan KC,Jiang P,Zheng YW,et al. Cancer genome scanning in plasma:detection of tumor-associated copy number aberrations,single-nucleotide variants,and tumoral heterogeneity by massively parallel sequencing[J]. Clin Chem,2013,59(1):211- 224.

[39]Paweletz CP,Sacher AG,Raymond CK,et al. Bias-corrected targeted next-generation sequencing for rapid,multiplexed detection of actionable alterations in cell-free DNA from advanced lung cancer patients[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2016,22(4):915- 922.

[40]Shaw JA,Page K,Blighe K,et al. Genomic analysis of circulating cell-free DNA infers breast cancer dormancy[J]. Genome Res,2012,22(2):220- 231.

[41]Murtaza M,Dawson SJ,Tsui DW,et al. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA[J]. Nature,2013,497(7447):108- 112.

[42]Chan KC,Jiang P,Chan CW,et al. Noninvasive detection of cancer-associated genome-wide hypomethylation and copy number aberrations by plasma DNA bisulfite sequencing[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2013,110(47):18761- 18768.

[43]Bettegowda C,Sausen M,Leary RJ,et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early-and late-stage human malignancies[J]. Sci Transl Med,2014,6(224):224r.

[44]Sausen M,Phallen J,Adleff V,et al. Clinical implications of genomic alterations in the tumour and circulation of pancreatic cancer patients[J]. Nat Commun,2015,6:7686.

[45]Garcia-Murillas I,Schiavon G,Weigelt B,et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer[J]. Sci Transl Med,2015,7(302):133r- 302r.

[46]Gall TM,Frampton AE,Krell J,et al. Cell-free DNA for the detection of pancreatic,liver and upper gastrointestinal cancers:has progress been made[J]. Future Oncol,2013,9(12):1861- 1869.

[47]Takai E,Totoki Y,Nakamura H,et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA for molecular assessment in pancreatic cancer[J]. Sci Rep,2015,16(5):18425.

[48]Murtaza M,Dawson SJ,Pogrebniak K,et al. Multifocal clonal evolution characterized using circulating tumour DNA in a case of metastatic breast cancer[J]. Nat Commun,2015,6:8760.

[49]Punnoose EA,Atwal S,Liu W,et al. Evaluation of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA in non-small cell lung cancer:association with clinical endpoints in a phase Ⅱ clinical trial of pertuzumab and erlotinib[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2012,18(8):2391- 2401.

[50]Zheng D,Ye X,Zhang MZ,et al. Plasma EGFR T790M ctDNA status is associated with clinical outcome in advanced NSCLC patients with acquired EGFR-TKI resistance[J]. Sci Rep,2016,6:20913.

[51]Francis G,Stein S. Circulating cell free tumour DNA in the management of cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci,2015,16(6):14122- 14142.

[52]Diaz LJ,Williams RT,Wu J,et al. The molecular evolution of acquired resistance to targeted EGFR blockade in colorectal cancers[J]. Nature,2012,486(7404):537- 540.

[53]Bertotti A,Papp E,Jones S,et al. The genomic landscape of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer[J]. Nature,2015,526(7572):263- 267.

[54]Spindler KL,Pallisgaard N,Andersen RF,et al. Changes in mutational status during third-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer-results of consecutive measurement of cell free DNA,KRAS and BRAF in the plasma[J]. Int J Cancer,2014,135(9):2215- 2222.

[55]De Mattos-Arruda L,Mayor R,Ng CK,et al. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma[J]. Nat Commun,2015,6:8839.

[56]Wei F,Lin CC,Joon A,et al. Noninvasive saliva-based EGFR gene mutation detection in patients with lung cancer[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med,2014,190(10):1117- 1126.

[57]Tsui DW,Berger MF. Profiling non-small cell lung cancer:from tumor to blood[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2016,22(4):790- 792.

[58]Crowley E,Di Nicolantonio F,Loupakis F,et al. Liquid biopsy:monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol,2013,10(8):472- 484.

Circulating Tumor DNA in Cancer Management

LI Miao-zhu1,LIN Jian-zhen2,ZHAO Hai-tao2

1Center for Population Health and Aging,Duke University,NC 27705,US2Department of Liver Surgery,PUMC Hospital,CAMS and PUMC,Beijing 100730,China

LI Miao-zhu Tel:1- 919- 813- 8269,E-mail:duke.dcssa.v@gmail.com;ZHAO Hai-tao Tel:13901246374,E-mail:zhaoht@pumch.cn

Molecular techniques can be very useful in detecting a patient’s tumor to guide treatment decisions is increasingly been applied in the care and management of cancer patients. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) containing mutations can be identified in the plasma of cancer patients during the course of the disease. As a non-invasive “liquid biopsies”,ctDNA is a potential surrogate for the entire tumor genome. The use of ctDNA might help to determine the disease prognosis,monitor disease progression,monitor the molecular resistance and monitor the tumor heterogeneity. Future developments will need to provide clinical standards to validate the ctDNA as a clinical biomarker and improve the reproducibility and accuracy,in order to be better exploited for personalized medicine.

circulating tumor DNA; tumour; gene mutation; dynamic monitor; heterogeneity

国际科技合作与交流项目(2015DFA30650)、公益性行业科研专项(201402015)、首都临床特色应用研究项目(Z151100004015170)和首都卫生发展科研专项(2014- 2- 4012)Supported by the Key Program for International S&T Cooperation Projects of China (2015DFA30650),the Special Scientific Research Fund (201402015),the Capital Clinical Research and Application of Special (Z151100004015170),and the Capital Health Research and Development of Special (2014- 2- 4012)

李妙竹 电话:1- 919- 813- 8269,电子邮件:duke.dcssa.v@gmail.com;赵海涛 电话:13901246374,电子邮件:zhaoht@pumch.cn

[R34]

A

1000- 503X(2016)05- 0594- 07

10.3881/j.issn.1000- 503X.2016.05.019

2016- 03- 10)