Homeopathic prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections following spinal cord injury: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial

2016-04-10rgenPannekSusannePannekRademacherMohinderJusrgKrebs

Jürgen Pannek, Susanne Pannek-Rademacher, Mohinder S. Jus, Jörg Krebs

1 Neuro-Urology, Swiss Paraplegic Centre, Nottwil, Switzerland

2 Homöopathie-pannek, Basel, Switzerland

3 SHI homöopathische Praxis, Zug, Switzerland

4 Clinical Trial Unit, Swiss Paraplegic Centre, Nottwil, Switzerland

INTRODUCTION

In the clinic, almost all patients with spinal cord injury (SCI)suffer from a neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction(NLUTD). The most severe consequence of NLUTD is renal dysfunction, which is the most common cause of death in this group of patients if untreated (Hackler, 1977). Standard treatment is the suppression of neurogenic detrusor overactivity(NDO), e.g., by antimuscarinic drugs, bladder evacuation,and intermittent catheterization (Groen et al., 2016).

Since the risk for renal damage could be substantially decreased by adequate urologic diagnostics and treatment(Groen et al., 2016), urologic care of SCI patients focuses on other urologic consequences of SCI, e.g., UTI. Symptomatic urinary tract infections (UTI) are one of the major and most common urologic problems in SCI patients. UTI occur in approximately 60% of the SCI patients after discharge from primary rehabilitation (Unsal-Delialioglu et al., 2010). They are the most common cause of septicemia and are associated with a significantly increased mortality (Biering-Sorensen et al., 1999; Esclarin De Ruz et al., 2000). In addition, they drastically impair the quality of life of the affected patients(Pannek, 2011).

The guidelines of the urologic and paraplegiologic associations agree that only symptomatic UTI should be treated(Everaert el al., 2009; Groen et al., 2016). Unfortunately,UTI recur frequently in SCI patients, and the bacteria are getting more resistive to antibiotics (Hinkel et al., 2004).If no morphologic or functional changes for recurrent UTI can be detected, UTI prophylaxis relies on medical treatment. Low-dose long-term antibiotics used frequently for the treatment of UTI have been demonstrated not to be effective, but to increase the risk of multi-resistive bacterial strains (Naber et al., 2001; Morton et al., 2002; Garcia Leoni and Esclarin De Ruz, 2003). As an alternative, a weekly oral cyclic antibiotic (WOCA) program is discussed, and initial results are promising, but data are sparse (Salomon et al., 2006).

The most popular non-antibiotic alternative is cranberry products for the treatment of UTI, but their usefulness in SCI patients has not been proven (Lee et al., 2007; Hess et al., 2008). No evidence regarding the efficacy of other plant extracts and bladder irrigation for urine acidification after SCI exists (Trautner and Darouiche, 2002; Pannek,2012). A small study gave a hint that oral immunotherapy with E.coli extracts may be effective in NLUTD patients following SCI (Hachen, 1990).

Recurrent UTI severely impairs the quality of life in the affected patients, but prophylaxis remains a try-and-error approach, because no evidence-based prophylaxis exists.Based on clinical experience, cranberries, urine acidification, long-term antibiotics and oral immunotherapy are the most frequently applied measures and are therefore regarded as the current standard (Pannek, 2012).

Homeopathy is a medical treatment with potentized drugs,which are chosen based on the law of similarity due to the individual signs and symptoms of the patient. Homeopathy relies on the concept of “vital force”. Disturbance of the vital force leads to symptoms. The appropriate remedy is found through analysis of the individual symptoms of the affected patients. Thus, the choice of the remedy is based on the patient’s complaints but not on a clinical diagnosis.Therefore, a specific remedy for diagnosis of UTI does not exist. The efficacy of homeopathy in treating UTI is well documented in several case series (Sparenborg-Nolte and Nolte, 2008; Pannek, 2014). However, no prospective study evaluating the use of homeopathy for prophylaxis of UTI in SCI patients has been performed.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study is to test the hypothesis that an adjunctive treatment with classical homeopathy (Hahnemann, 2005) leads to a reduction in the rate of recurrent UTI in SCI patients and to assess if homeopathic treatment will significantly improve patient’s satisfaction and quality of life.

METHODS/DESIGN

Study design

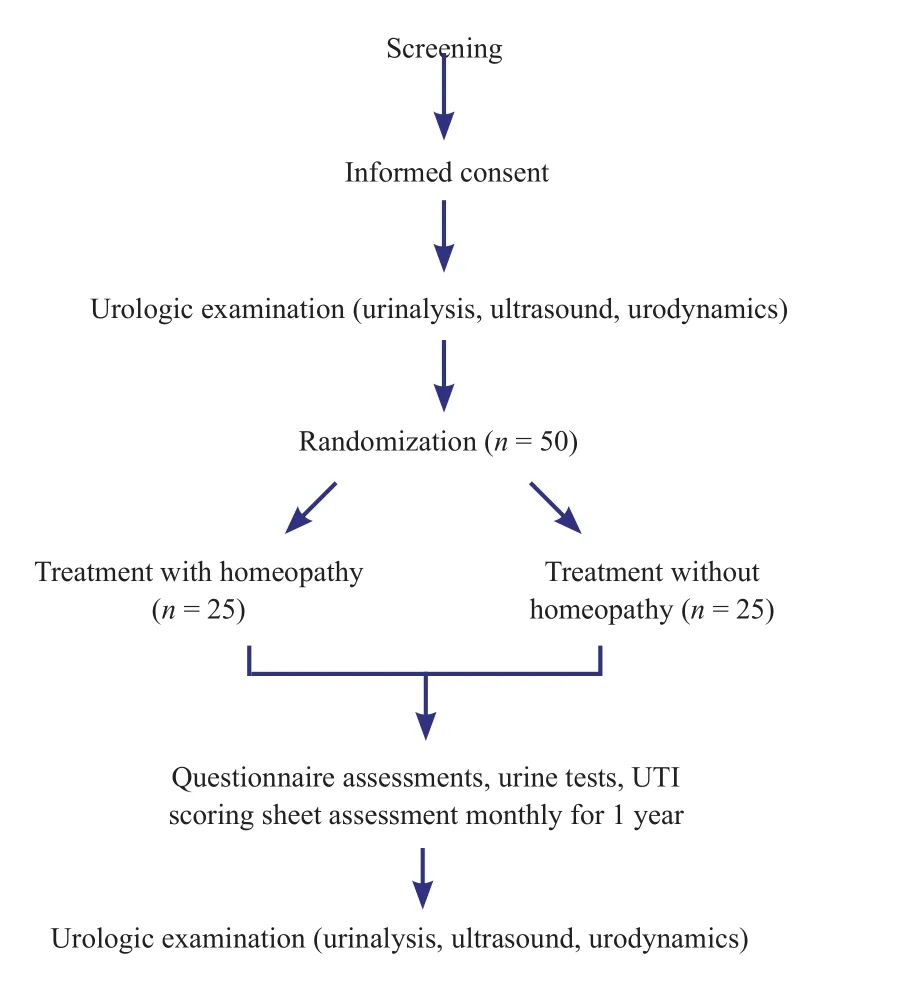

This is a prospective, single-center, randomized, parallel group controlled trial that will be held at the Swiss Paraplegic Centre in Nottwil, Switzerland. After having given written informed consent, the included SCI patients with recurrent UTI (n = 50) will be equally randomized to one of the two mentioned groups:

Group 1 (n = 25): Patients receiving standard care for prophylaxis (cranberries, urine acidification, long-term antibiotics and oral immunotherapy).

Group 2 (n = 25): Patients receiving standard care for prophylaxis as described above plus adjunctive classical homeopathy (Hahnemann, 2005).

This project is approved by Ethikkommission Nordwestund Zentralschweiz (EKNZ): PB_2016-00054XXX. The design is described in Figure 1.

Study population and recruitment

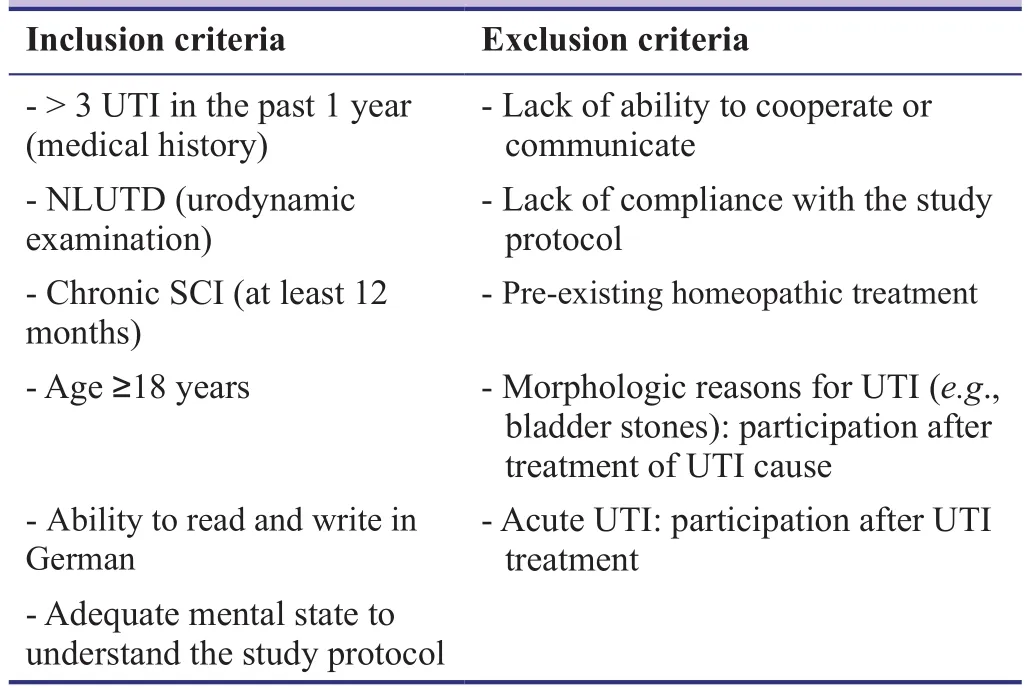

All consecutive SCI patients with NLUTD who present at the outpatient service of the neuro-urology of the Swiss Paraplegic Centre, are asked, as part of the medical history, about the number of UTI they suffered from in the past one year. All patients who reported at least 3 UTI/year were offered to be screened for the study. For inclusion and exclusion criteria, see Table 1.

Figure 1: Study flow chart.

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Sample size

Based on clinical experience and on our own data (Krebs et al., 2016), we assumed a UTI rate of 5 UTI/year and a reduction of the UTI rate of 25%. For equal allocation of the two groups, the total sample size required when considering a dropout rate of 10% is 50 participants. Given a standard deviation of 30%, 25 participants per group are needed (power= 80%, level of significance α = 0.05). Power analysis was done with R software environment (version 3.1.0, Copyright 2014, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Baseline evaluation

Bsaseline evaluation consisted of a detailed and standardized medical interview, including the method of bladder evacuation, the drugs used, and the number of UTI within the last year. To assess the state of the upper and lower urinary tract, a video-urodynamic test, and ultrasound of the bladder and the kidneys was performed. Urinalysis and serum cystatin C for renal function were assessed.

Randomization

Participants will be randomly allocated to either the group 1 or group 2 after the baseline assessment. The randomization is performed according to computer generated random allocation treatment codes. The randomization list is kept by an independent investigator not involving in the care or assessment of the participants, or in the data collection and analysis. Randomization was performed with the SPSS software (version 18.0.3, IBM, Somers, NY, USA).

Interventions

Patients receiving adjunctive homeopathic treatment will be treated by an experienced certified homeopath from the“SHI homeopathic centre” in Zug, Switzerland.

All participants will be educated about the possible signs and symptoms of a UTI. They receive a standardized document listing the typical symptoms of UTI in patients with SCI, which is based on the current definition of the ISCoS (International Spinal Cord Society) (Goetz et al.,2013). Whenever symptoms occur, participants fill out a documentation sheet and test the urine with a dipstick test(leucocytes and nitrite). Acute UTI that occur during the study period are treated as usual.

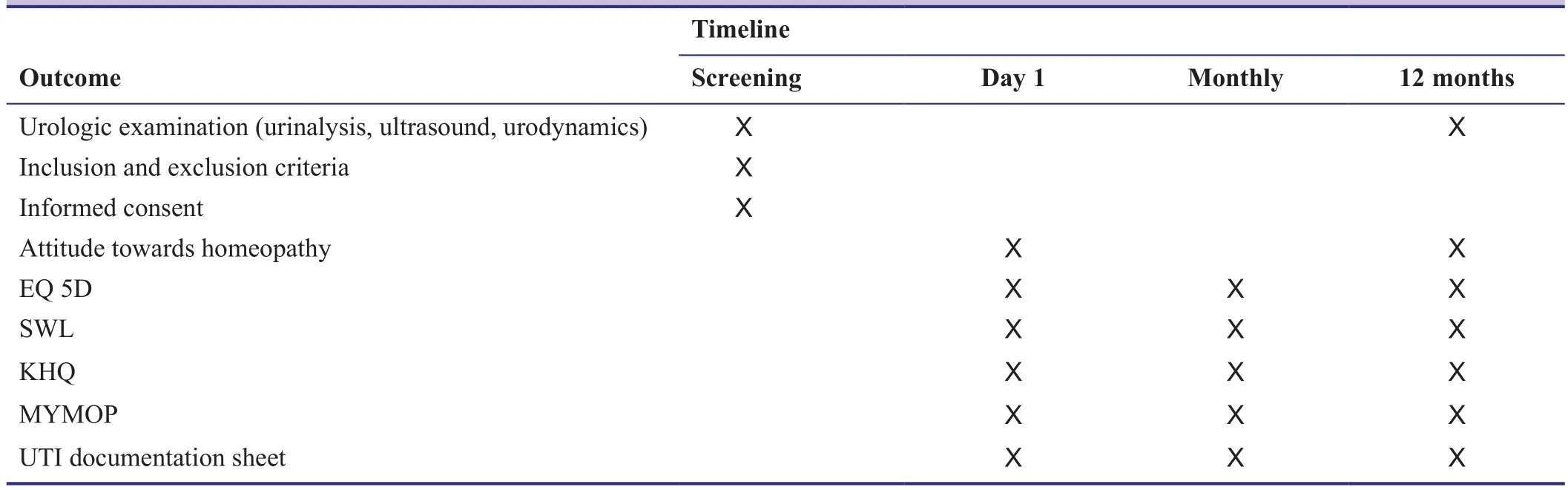

After a follow-up period of 1 year, with the monthly application of the urine tests and questionnaires listed below,a final evaluation and close-out visit will be performed. At that visit, the baseline examinations will be repeated, and the questionnaires mentioned below will be filled in.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure is the number of UTI per year.The number of UTI within the year before the study was assessed by medical history alone. The number of UTI during the study period was assessed by medical history(interview after 12 months) and, in addition, the UTI occurring during the study period are documented with the documentation sheet mentioned above. The sheets are collected by the patients and monthly sent to our center. If no UTI occur during a month, a documentation sheet stating this fact will be returned.

Secondary outcome measures are the satisfaction with the homeopathic treatment and the quality of life. Standardized, validated questionnaires are used to assess patients’satisfaction with the treatment (MYMOP [Measure yourself medical outcome profile] questionnaire (Paterson and Brit-ten, 2000)), urology-specific quality of life (King’s Health Questionnaire (Bjelic-Radisic et al., 2005)), and general quality of life (EuroQol EQ 5D (Rabin and de Charro,2001) and “Satisfaction with life scale (SWL)” (Diener et al., 1985)). The MYMOP, EQ5D, and SWL are filled in monthly, the King’ s Health Questionnaire at the beginning and at the end of the study. In addition, patients reported their attitude towards homeopathy at the beginning and at the end of the study, using a standardized questionnaire(Pannek-Rademacher, 2011) (Table 2).

Table 2: Time course of the study

Statistical analysis

The inter-group difference regarding the number of patients with UTI during the observation period will be analyzed by a chi-square test based on a 2 × 2 contingency table. The intergroup difference of the UTI rate within the observation period, group-specific patient satisfaction with homeopathy and the quality of life will be tested using the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametrical data. The changes in patients satisfaction and quality of life over the study period (comparison before-afterwards) will be analyzed using the Wilcoxon test.

DISCUSSION

Significance of this study

Recurrent UTI remain to be one of the most common problems in patients with NLUTD due to SCI. Despite multiple efforts, solid data about the efficacy and safety of prophylactic measures in this patient cohort are scarce. A plethora of different treatments are currently in use (Pannek, 2012), although no evidence-based proof of efficacy exists, and some of those are even associated with adverse long-term effects. As UTI are associated with significant mortality and an impaired quality of life (Biering-Sorensen et al., 1999; Pannek, 2011), the detection of an effective UTI prophylaxis for SCI patients would be of high relevance for the affected persons, leading to a significant improvement of their quality of life and reduction of morbidity.

Advantages and limitations of this study

Homeopathy has been demonstrated to be without serious long-term risks, there is a high demand by the patients (Pannek et al., 2015), and its possible usefulness has been demonstrated in case studies (Pannek et al., 2014). Homeopathy is not associated with significant side effects; therefore the drugs used in this study are safe for the participants. The results of the study will significantly add to our knowledge not only about UTI prevention, but the clinical value of homeopathy. As the number of persons with SCI living in Switzerland is comparatively small when compared to other diseases, the number of possible participants is limited.

Evidence for contribution to future studies

If homeopathy was an effective prophylaxis in SCI patients,suffering by definition from complicated UTI, it may also have a positive effect in persons with uncomplicated recurring UTI, which is a far larger group of patients. Thus,the results from our study may foster further research on recurrent UTI in other patient cohorts.

TRIAL STATUS

Recruiting is ongoing at the time of submission.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they will obtain all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) will give his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author contributions

JP, SPR, MSJ, and JK conceived and designed the study, acquired data, and drafted the manuscript. MSJ made substantial contributions and revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Plagiarism check

This paper was screened twice using CrossCheck to verify originality before publication.

Peer review

This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Biering-Sorensen F, Nielans HM, Dorflinger T, Sorensen B (1999)Urological situation five years after spinal cord injury. Scand J Urol Nephrol 33:157-161.

Bjelic-Radisic V, Dorfer M, Tamussino K, Greimel E (2005) Psychometric properties and validation of the German-language King's Health Questionnaire in women with stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 24:63-68.

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess 49:71-75.

Esclarin De Ruz A, Garcia Leoni E, Herruzo Cabrera R (2000) Epidemiology and risk factors for urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injury. J Urol 164:1285-1289.

Everaert K, Lumen N, Kerckhaert W, Willaert P, van Driel M (2009)Urinary tract infections in spinal cord injury: prevention and treatment guidelines. Acta Clin Belg 64:335-340.

Garcia Leoni ME, Esclarin De Ruz A (2003) Management of urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injuries. Clin Microbiol Infect 9:780-785.

Goetz LL, Cardenas DD, Kennelly M, Bonne Lee BS, Linsenmeyer T, Moser C, Pannek J, Wyndaele JJ, Biering-Sorensen F (2013)International Spinal Cord Injury Urinary Tract Infection Basic Data Set. Spinal Cord 51:700-704.

Groen J, Pannek J, Castro Diaz D, Del Popolo G, Gross T, Hamid R,Karsenty G, Kessler TM, Schneider M, 't Hoen L, Blok B (2016)Summary of European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines on Neuro-Urology. Eur Urol 69:324-333.

Hachen HJ (1990) Oral immunotherapy in paraplegic patients with chronic urinary tract infections: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Urol 143:759-762.

Hackler RH (1977) A 25-year prospective mortality study in the spinal cord injured patient: comparison with the long-term living paraplegic. J Urol 117:486-488.

Hahnemann S (2005) Organon der Heilkunst, 6. Auflage. Marix,Wiesbaden.

Hess MJ, Hess PE, Sullivan MR, Nee M, Yalla SV (2008) Evaluation of cranberry tablets for the prevention of urinary tract infections in spinal cord injured patients with neurogenic bladder.Spinal Cord 46:622-626.

Hinkel A, Finke W, Bötel U, Gatermann SG, Pannek J (2004) Increasing resistance against antibiotics in bacteria isolated from the lower urinary tract of an outpatient population of spinal cord injury patients. Urol Int 73:143-148.

Krebs J, Wöllner J, Pannek J (2016) Risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infections in individuals with chronic neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Spinal Cord 54:682-686

Lee BB, Haran MJ, Hunt LM, Simpson JM, Marial O, Rutkowski SB, Middleton JW, Kotsiou G, Tudehope M, Cameron ID (2007)Spinal-injured neuropathic bladder antisepsis (SINBA) trial. Spinal Cord 45:542-550.

Morton SC, Shekelle PG, Adams JL, Bennett C, Dobkin BH, Montgomerie J, Vickrey BG (2002) Antimicrobial prophylaxis for urinary tract infection in persons with spinal cord dysfunction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 83:129-138.

Naber KG, Bergman B, Bishop MC, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, Botto H, Lobel B, Jinenez Cruz F, Selvaggi FP; Urinary Tract Infection(UTI) Working Group of the Health Care Office (HCO) of the European Association of Urology (EAU) (2001) EAU guidelines for the management of urinary and male genital tract infections.Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Working Group of the Health Care Office (HCO) of the European Association of Urology (EAU).Eur Urol 40:576-588.

Pannek J (2011) Treatment of urinary tract infection in persons with spinal cord injury – guidelines, evidence and clinical practice J Spinal Cord Med 34:11-15.

Pannek J (2012) Prophylaxis of urinary tract infections in subjects with spinal cord injury and bladder function disorders - current clinical practice. Aktuelle Urol 43:55-58.

Pannek J, Pannek-Rademacher S, Jus MC, Jus MS (2014) Usefulness of classical homoeopathy for the prevention of urinary tract infections in patients with neurogenic bladder dysfunction: A case series. Indian J Res Homoeopathy 8:31-36.

Pannek J, Pannek-Rademacher S, Wöllner J (2015) Use of complementary and alternative medicine in persons with spinal cord injury in Switzerland: a survey study. Spinal Cord 53:569-572.

Pannek-Rademacher S (2011) Sind Globuli und Intensivmedizin kompatibel? intensiv 19:232-235.

Paterson C, Britten N (2000) In pursuit of patient-centred outcomes:a qualitative evaluation of the 'Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile'. J Health Serv Res Policy 5:27-36.

Rabin R, de Charro F (2001) EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 33:337-343.

Salomon J, Denys P, Merle C, Chartier-Kastler E, Perronne C, Gaillard JL, Bernard L (2006) Prevention of urinary tract infection in spinal cord-injured patients: safety and efficacy of a weekly oral cyclic antibiotic (WOCA) programme with a 2 year followup--an observational prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother 57:784-788.

Sparenborg-Nolte A, Nolte S (2008) Homöopathie und Naturheilverfahren - eine sinnvolle Kombination am Beispiel des akuten Harnwegsinfektes. AHZ 253:224-228.

Trautner BW, Darouiche RO (2002) Prevention of urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 25:277-283.

Unsal-Delialioglu S, Kaya K, Sahin-Onat S, Kulakli F, Culha C,Ozel S (2010) Fever during rehabilitation in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury: analysis of 392 cases from a national rehabilitation hospital in Turkey. J Spinal Cord Med 33:243-248.

杂志排行

Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Trials:Nervous System Diseases的其它文章

- Utilization patterns of benzodiazepines in psychiatric patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital

- Effectiveness of cerebellar repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in essential tremor: study protocol for a randomized, sham-controlled trial

- Bispectral index-guided fast track anesthesia by sevoflurane infusion combined with dexmedetomidine for intracranial aneurysm embolization: study protocol for a multi-center parallel randomized controlled trial

- Cognitive function and biomarkers after traumatic brain injury:protocol for a prospective inception cohort study

- Electroencephalographic changes following trigeminal nerve stimulation for major depressive disorder: study protocol for a randomized sham-controlled trial

- Effect of intravenous acetaminophen on post-operative opioidrelated complications: study protocol for a randomized,placebo-controlled trial