Governance of protected areas: Kara Kara National Park, Victoria

2015-12-12GAOYunXUPengDAIWenbinWENXueru

GAO Yun, XU Peng, DAI Wen-bin, WEN Xue-ru*

1Institute of Hydrogeology and Environmental Geology, Shijiazhuang 050061, China

2School of Land and Food, Department of Environmental Study and Geography, Tasmania University, Tasmania 7005, Australia.

Abstract: This study explains various modes that can be applied for protected area. It analyses the requirements for good governance of protected area. A study area (Kara Kara National Park) is selected for identifying key challenges for implementing good governance of protected area. The challenges of good governance of protected area were investigated in this paper. The last part is based on the results from the third section and explores the strategies for addressing these challenges.

Keywords: Protected area; Implementation of challenges; Legislative support; Financing support; Local communities; Stakeholders

Introduction

Governance refers to the interactions among structures, processes and traditions that determine how power and responsibilities are exercised, how decisions are made and how the views of citizens or stakeholders are incorporated in decisionmaking (Graham P H and Vance C P, 2003).Governance is now also considered as a critical aspect for protected areas. Through the decades,the expectation for good governance of protected areas around the world has grown and been improved by substantial changes.

The case study area

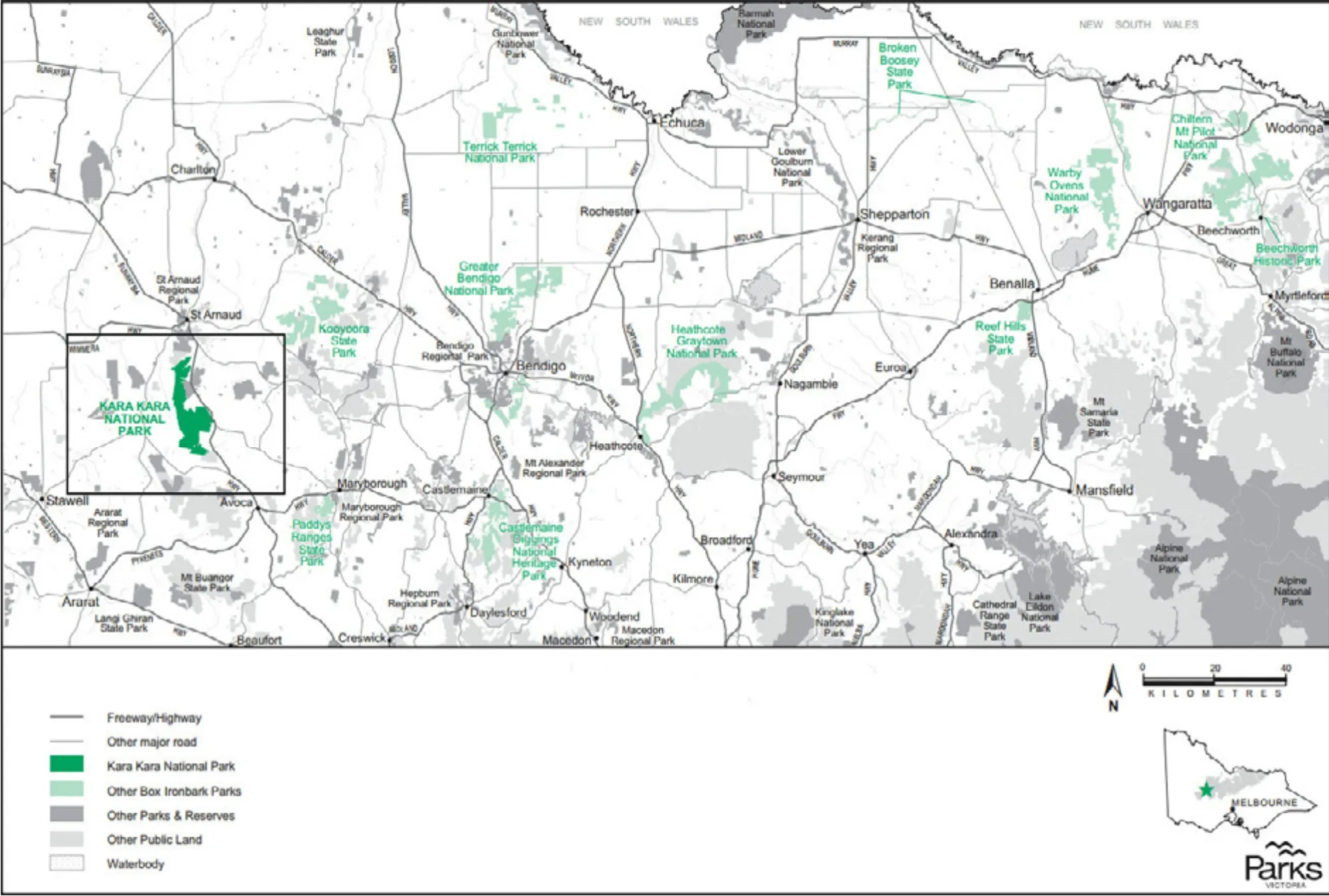

This paper selects Kara Kara National Park(see Fig. 1) as the study area through which we investigate the challenges of good governance of protected area. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a protected area as a “clearly defined geographical space,recognised, dedicated and managed, by legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” (Borrini-Feyerabend G et al. 2013). According to the IUCN classification system for protected areas, Kara Kara National Park is a Category II protected area and located in approximately 190 km north-west of Melbourne, west of the Sunraysia Highway. It holds conservation significance for its protection of the largest, relatively intact area of Box-Ironbark forest and woodland in Victoria(Parks Victoria, 2013). Furthermore, Kara Kara has positive impacts for local communities in terms of the indigenous value protected within the park. On a regional scale, Kara Kara National Park contributes to the protection of natural assets and the maintenance of sustainable woodland. Our paper identifies the key challenges in implementing good governance of Kara Kara and recommends strategies for further improvement.

Fig.1 Kara Kara National Park (Parks Victoria, 2013)

1 Modes for governance of protected areas

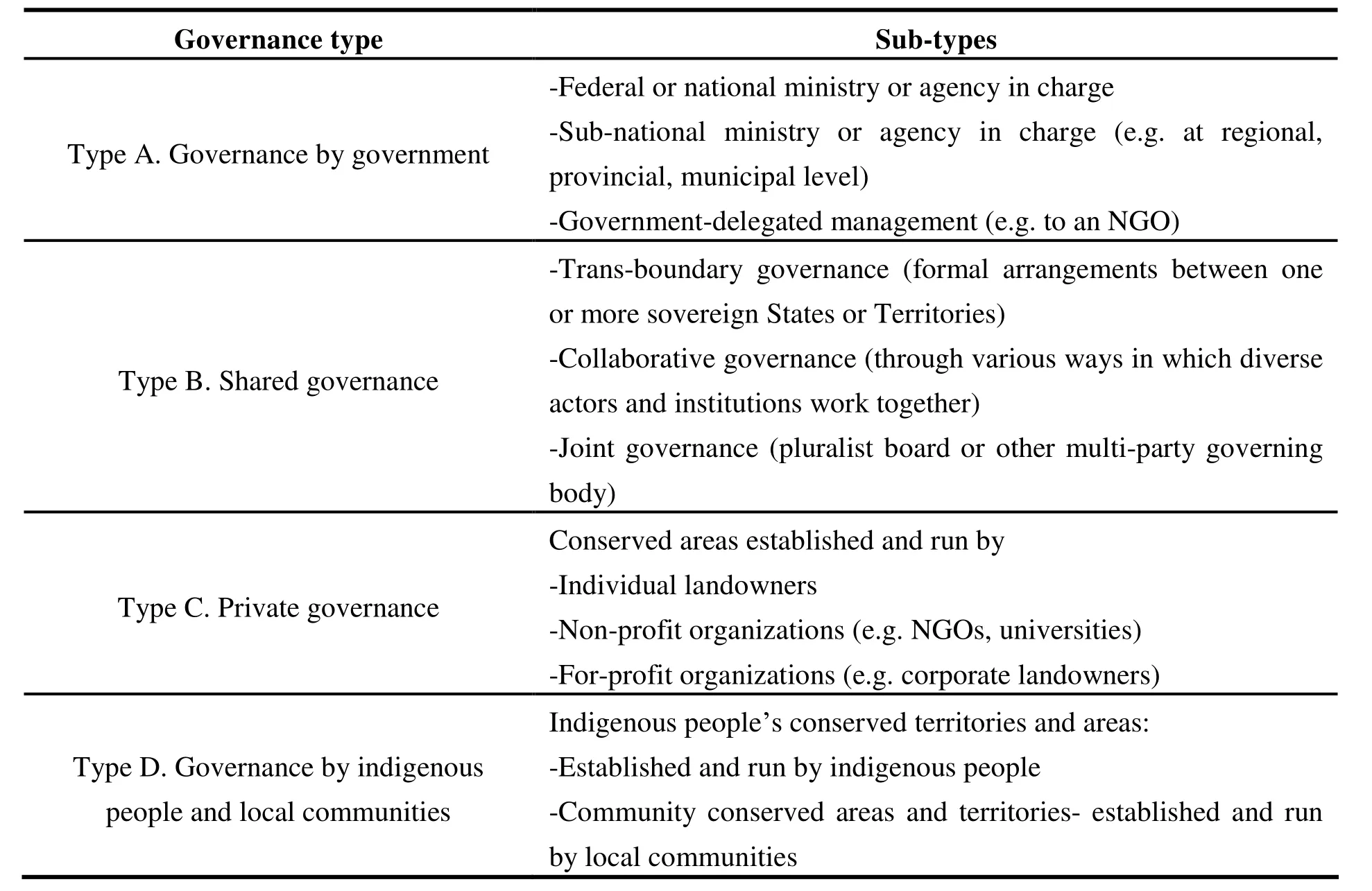

Different types of governance can be applied to various protected areas. Protected areas in Australia are generally held both important natural values and indigenous values for local communities. Since the 19thcentury, the designation of protected area has been predominantly determined by the government(Borrini-Feyerabend G et al. 2013). The responsibility for governance of Australian protected areas over time has been via a combination of national laws, policies, agencies,sub-national institutions, and community-based and private initiatives. Recently, the IUCN and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)acknowledged that governance of protected areas can be categorised into four different types(Dudley N, 2008). Table 1 details these four governance types for protected areas (IUCN,2004).

1.1 Governance by government

Government agencies at various levels (federal,state and local) make and enforce decisions for the governance of protected area. People are familiar with this type of governance because most protected areas are owned by national governments and directly managed by local or state authorities.The government has the responsibility to decide the management objectives for the specific protected area and is accountable for its conservation goals. In most cases, governments also own the natural assets within protected areas.Kara Kara National Park, for example, is managed under the National Park Act and administrated by Parks Victoria. It is known for its natural, cultural,recreational and tourism values. The national government has full ownership and control and oversight for the protected area under this type of governance (Borrini-Feyerabend G et al. 2013).

Table 1 IUCN Governance types for protected areas (IUCN, 2004)

1.2 Shared governance

Protected areas under shared governance are based on institutional mechanisms and process which formally and/or informally share authority and responsibility among several actors. This model is widely used, and many countries have been experimenting with it, sometimes adopting specific laws, policies and administrative arrangements to ensure the success of shared governance (Locke H and Dearden P, 2005).Shared governance is not specific to protected areas, but is also used in many other fields and settings (Borrini-Feyerabend G et al. 2002).Shared governance is a good way to strengthen the quality of decision-making processes and achieves better agreement on management of protected areas. Eagles (2008) demonstrated seven typical models of protected area governance and apply these models into different combinations of land ownership, management and income source.Although Kara Kara does not employ shared governance, long settled landscapes and farmed areas benefits could be achieved if the Kara Kara Park management utilised a variety of actors.

1.3 Private governance

Private nature reserves created by NGOs are increasing in number and extent around the world,thereby becoming a potential major contributor to biodiversity goals at a global scale. Private governance comprises protected areas under individual, NGO or corporate control and/or ownership, which are often referred to as “private protected areas”. Sometimes, a lot of biodiversity can be found on these private lands managed by private owners. Private governance of these areas can be conducted by various kinds of stakeholders,including individuals, corporations and nongovernmental organizations (Borrini-Feyerabend G et al. 2008). These stakeholders are all capable of owning responsibility for protection of the private land and in maintaining its ecological values. As with other types of governance, the most important factor in determining the scope and direction of private governance is the legal and social environment in which they operate (Borrini-Feyerabend G et al. 2008). In order to encourage the private sector to engage in conservation, to be accountable and innovative, and to adopt sustainable economic practices, protected area management goals should be based on a conservation ethic and include a sound framework for natural resource governance at local and national levels.

1.4 Governance by indigenous people and local communities

There are two main categorical subsets under the umbrella of indigenous and community governance. One is the indigenous areas and territories conserved by indigenous people, and the second is community conserved areas established and run by local communities (Worboys G L et al.2015). The term ‘Indigenous People and Community Conserved Territories and Areas’(ICCAs) is now being used to describe “natural and/or modified ecosystems, containing significant biodiversity values, ecological benefits and cultural values, voluntarily conserved by indigenous people and local communities, both sedentary and mobile, through customary laws or other effective means” (Borrini-Feyerabend G et al.2004). According to Borrini-Feyerabend’s article,approximately 22% of the earth’s terrestrial surface is conserved as indigenous territories and comprises 80% of planet’s biodiversity. Kothari et al. (2012) also presents data showing that ICCAs may outnumber the officially designated protected areas but these authors claim only 13% of earth’s surface is covered by ICCAs. Nevertheless, the data on all sides is significant to impress the importance of identifying potential opportunities within these indigenous territories and understanding the mechanisms for governance by non-indigenous local communities.

2 Requirements for good governance of protected area

The four modes for protected area governance previously outlined are via national and state governments, shared partnerships, and private ownership and through indigenous people and local communities. In order to maintain the quality of each model, it is necessary to identify the potential requirements for good governance of protected areas. Lockwood (2010) has listed seven principles in relation to protected areas which we will analyse according to the four governance modes and best practice for good governance of protected areas.

2.1 Requirements for legislative support

As previously discussed, most protected areas are governed directly by governments at a national,state or local level. However, legislative standards must be clearly defined in order for government officials to conduct management goals, notify the administrative authorities and instruct managers for the particular protected areas. Therefore, good legislation and sound management policies are the primary requirements for good governance of protected areas by the government.

It is well known that legislations provide people with standards to adhere to and follow. For legislation to have effect, it is necessary to recognize ramifications for individuals, groups or other organizations that break the legislative rules,which usually entail punishment by the law or the relevant policy. The state or federal government are under serious obligation to develop a comprehensive law system to support the governance of protected areas (Borrini-Feyerabend G, 1996). Furthermore, responsible governments should construct specific departments dedicated to the governing of protected areas and a relevant authority or representative needs to be in place so that communities who have links to a given protected area can interact with and report up to the state and national government on matters relating to their protected area.

2.2 Requirements for financial support

Requirements for financial support in protected areas are mainly relevant to private governance of private protected areas. People who are interested in the protected area are responsible for protecting the natural value of the area. However, the power of individuals is limited. Good protected area governance needs a comprehensive supply chain to provide funds to the projects, recreational activities,infrastructure and indigenous developments for local communities. It is significant to ensure that the financing chain is secured and the flow of funds is consistent. The role of private governance needs to be better supported and understood by the wider community, as these outside organizations and interested individuals are responsible for protecting wild biodiversity, and spiritual support alone is not enough to provide them with the long-term financial security they need (Locke H and Dearden P, 2005). Private governance is the most desirable type of governance for financing support from people or organizations with interest in the protected area.

2.3 Requirements for local communities

Local community requirements for protected area governance mainly relate to those such as indigenous communities and traditional landowners. A major portion of protected areas are held by indigenous people who live in or around them and who tend to maintain their viability. As previously discussed in previous sections of this paper, many protected areas are surrounded by indigenous communities and aboriginal residents.The cultural value and historical significance of protected areas to these indigenous communities needs to be protected by good governance. Good governance of the protected areas the indigenous people rely on is not only important in order to improve the quality of life in their respective communities, but it is also important to maintain the number and quality of aboriginal places and historical sites for others (Borrini-Feyerabend G and Lassen B, 2010). As well as ensuring good governance, engagement with local communities needs to be enhanced by providing them with greater opportunities to manage their lands. Public awareness about the role local communities can play in protected area management is still at a low level. Furthermore, relevant authorities can benefit from traditional knowledge, by harnessing historical and contextual information from traditional landowners and noting their aspirations for the future of the protected area. In addition, it is vital for good governance at a local scale, that indigenous communities are involved with the management of protected areas (Borrini-Feyerabend G et al. 2002).

2.4 Requirements for stakeholders

Shared governance specifically involves requirements for stakeholders. Given that shared governance can include many and various stakeholders, requirements for meaningful engagement of effective stakeholders should also be valued as a part of good governance of protected areas.

In the first place, the stakeholders must have a strong sense of the values and threats related to their particular protected area and take the responsibility for its protection. To ensure stakeholders are aware of these values and threats,educational programs, training projects and educational tours of protected areas can be organised. Secondly, the visitors’ experiences can also be improved by inclusion in such programs.Increased visitation to protected areas may be encouraged by including visitors in these educational tours and providing them with qualitative services. Finally, relevant authorities and stakeholders must work towards the same goal to improve governance in their protected area.

3 Key challenges for implementation of good governance of Kara Kara National Park

The five main requirements for protected area governance discussed above are vital alone or in combination to good governance given protected area which cannot meet one or all of these requirements, indicates the area has numerous challenges to the delivery of good governance.This report chooses Kara Kara National Park as a study area to demonstrate the challenges of implementing good governance of protected areas.Kara Kara National Park has been recognized as the most valuable place for protecting Victoria’s viable, comprehensive, and adequate representative samples of the natural environment. It provides visitors with valuable opportunities to experience outstanding natural scenes and dynamic cultural resources (Parks Victoria, 2013).Nevertheless, there exists are a number of challenges for implementing protected area governance. The key challenges are identified in the following four categories.

3.1 Challenges for the conservation of natural values

According to the Kara Kara Management Plan,the main challenges to the conservation of natural values of the National Park are:

(1) The near-natural age class distribution,structure, disturbed areas and floristic diversity that still exist throughout most of the park are preserved;

(2) The populations of threatened flora and fauna species are maintained;

(3) The quality of fauna refuges, large old trees and woody debris on the ground are maintained;

(4) Resourcing an integrated response to extensive or emerging threats at a landscape scale;

(5) Human interference to the Mount Separation Reference Area is kept to a minimum;

(6) The links between community partners and local government are enhanced to protect and restore native vegetation links and reduce habitat fragmentation;

(7) The impact of works and infrastructure on natural values are reduced;

(8) The role of fire in meeting the requirements of floristic communities in the park are researched and monitored.

3.2 Challenges for the conservation of cultural values

Kara Kara National Park is a valuable resource for the local area in terms of exposure to indigenous culture, with strong associations to aboriginal places and objects as well as historical places. The main challenges for implementing good governance in this respect are:

(1) Protection of aboriginal places and objects from interference or damaging activities;

(2) Promotion and interpretation of traditional knowledge with respect to the views of traditional owners;

(3) Protection of historical sites from interference or inappropriate activities;

(4) To avoid the impact of any works and infrastructure on the park’s cultural values;

(5) To encourage and support research into the aboriginal and historic culture heritage of the park and consult with traditional owners and other interested communities.

3.3 Challenges for visitor management

Due to the geographical advantage of the park in close proximity to and easily accessed by the large city of Melbourne, Kara Kara attracts many visitors each year for recreational activities and natural experiences. Unique and picturesque niches hold special significance for visitors who have previously explored the park. Furthermore, the Rocky ridges provide people with vantage points for landscape viewing and the opportunity to experience solitude within the vast expanse of the park (Parks Victoria, 2013). Challenges for Kara Kara’s visitor management are:

(1) Enhancement of visitors and local community’s understanding and appreciation of the park’s natural and cultural values by a range of information services, and interpretation and education programs;

(2) Enhancement of the opportunity for ready access to the park and enjoyment of solitude in the natural forest and grassy woodland settings;

(3) Promotion of the park as a regional destination and a unique Box-Ironbark experience;

(4) Enhancement of the visitors and local community’s enjoyment through recreational activities;

(5) Maintenance of a range of recreational activities (such as walking, bike riding, horse riding, kayaking, bird watching) at a sustainable level;

(6) Encourage visitors to adapt minimal-impact techniques and to adhere to standards developed by outdoor recreational industries.

3.4 Challenges for community awareness and involvement

Kara Kara National Park is surrounded by nearby towns of Avoca, Maryborough and St Arnaud and attracts visitors from near and a far along the Sunraysia Highway to view the park’s natural assets. It is important for the future of Kara Kara that it continues to attract visitors and improve engagement with stakeholders in the surrounding region through increasing public awareness of the park’s natural and cultural values.The following challenges are outlined and indicate the difficulty of improving community awareness and involvement.

(1) Development of a strong collaborative partnership with traditional owners and relevant registered aboriginal organisations to facilitate reflection and recording of indigenous knowledge,interests, and aspirations for the planning and management of Kara Kara;

(2) To encourage wider community to gain awareness of the park’s values and an appreciation of the knowledge and aspirations of traditional owners and indigenous communities;

(3) To encourage local communities and visitors to develop a sense of custodianship for Kara Kara National Park through joining volunteer working and social groups focusing on park activities and/or becoming involved in park management;

(4) To improve opportunities for communities,individuals, groups and relevant agencies to share their interest and raise concerns relating to the park and its management( this could be for example, via a combination of engagement modes such as surveys, audits, public meetings, forums, and newsletters).

4 Recommended strategies for good governance of Kara Kara National Park

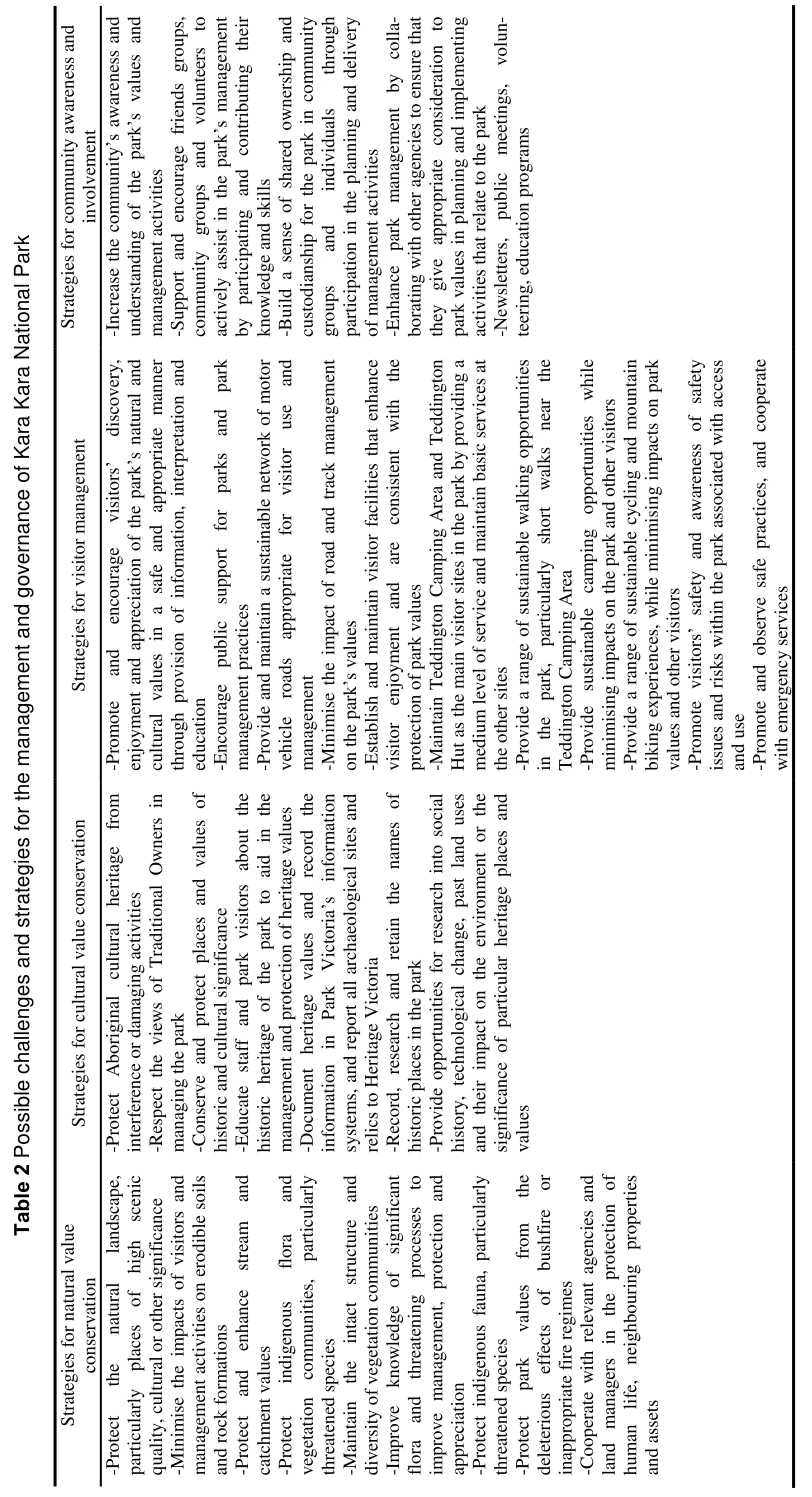

There are four key challenges for implementing good governance in Kara Kara National Park: (1)conservation of natural values, (2) conservation of cultural values, (3) visitor management, (4)community awareness and engagement. To ensure good governance, a set of strategies must be developed to address these challenges. Table 2 outlines the potential strategies that could be employed to overcome the governance challenges identified for Kara Kara National Park.

5 Conclusions

Over the last decade, there has been a strong pursuit for good governance of protected areas around the world. For this pursuit to be fruitful, it is important for people to understand the meaning of different governance models for protected areas.This report has summarized the essential requirements for good governance of protected area. In order to gain further understanding of the challenges and strategies behind the implementation of good governance, this report has explored the study area Kara Kara National Park. The main concerns for implementation of good governance in the study area are associated with the site’s specific natural and cultural significance. Four key challenges to the implementation of good governance of Kara Kara National Park have been brought to light in this report: (1) conservation of natural values, (2)conservation of cultural values, (3) visitor management, (4) community awareness and engagement. Relevant strategies have been proposed to address these challenges and provide guidance for good governance of protected area into the future. Overall, the necessity of good governance of protected area should be valued in all dimensions and relevant authorities and communities should build a good governance plan based on realistic and site-specific goals.

杂志排行

地下水科学与工程(英文版)的其它文章

- Analysis of the negative effects of groundwater exploitation on geological environment in Asia

- Specific yield of phreatic variation zone in karst aquifer with the method of water level analysis

- Application of remote sensing technique to mapping of the map series of karst geology in China and Southeast Asia

- Compilation of Groundwater Quality Map and study of hydrogeochemical characteristics of groundwater in Asia

- Evaluation on water resources carrying capacity of Changchun-Jilin Region

- Comparison of 1,2,3-Trichloropropane reduction and oxidation by nanoscale zero-valent iron, zinc and activated persulfate