Purification of a Diatom and Its Identification to Cylindrotheca closterium

2015-04-05WANGSongZHANGLinYANGGuanpinZHUBaohuaandPANKehou

WANG Song, ZHANG Lin, YANG Guanpin, ZHU Baohua, and PAN Kehou,

1)Laboratory of Applied Microalgae Biology,Key Laboratory of Mariculture of Ministry of Education of China,Ocean University of China,Qingdao266003,P. R. China

2)College of Marine Life Sciences,Ocean University of China,Qingdao266003,P. R. China

Purification of a Diatom and Its Identification to Cylindrotheca closterium

WANG Song1), ZHANG Lin1), YANG Guanpin2), ZHU Baohua1), and PAN Kehou1),*

1)Laboratory of Applied Microalgae Biology,Key Laboratory of Mariculture of Ministry of Education of China,Ocean University of China,Qingdao266003,P. R. China

2)College of Marine Life Sciences,Ocean University of China,Qingdao266003,P. R. China

A diatom was purified with colony selection and continuous dilution methods. It was identified toCylindrotheca closteriumaccording to its morphological characteristics andrbcLand 18s rRNA gene sequences. The alga was not sensitive to ampicillin and neomycin, but sensitive to chloramphenicol which inhibited its growth at concentrations ranging from 50 to 150 μg mL-1. The purified alga was easy to culture and its specific growth rate was 0.207 ± 0.002 (d-1). It was resistant to pollution and could be harvested in an easy way. It was relatively high in lipid content (20.08% ± 0.67% of dry weight) and the combined amount of its 16:0 and 16:1 (n-7), the most suitable resource of biodiesel, was as high as 64% of the total fatty acids, while the amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids reached 19.96%-20% of the total fatty acids. Thus the purifiedC. closteriumcan be cultured as a biodiesel producer or a nutrition supplement producer.

Cylindrotheca closterium; antibiotics sensitivity; fatty acid composition; total lipid content

1 Introduction

Diatoms are a main group of microalgae, and are highly diverse. More than 200 genera and 100000 species have been recorded in this group (Mann, 1989). Diatoms are widely distributed in seawater, fresh water, soil and moist surface. Although diatoms often aggregate into communities, they are unicellular and diverse in shapes with sizes varying from a few to hundreds of micrometers. These algae are the main primary producers in seawater and play a crucial role in global carbon cycle (Trégueret al., 1995; Fieldet al., 2003). The most prominent feature of diatoms is their silicic shells which enable them to sink to the bottom under some conditions. This performance makes their harvest easy, which are highly appreciated by algal culturing community. Diatoms have been cultured for a long time as the feed of aquaculture animals (Lebeau and Robert, 2003; Xuet al., 2012), the tester of estuary sediment toxicity (Ignacioet al., 2007) and PUFA producers (Wang and Zeng, 2007). In recent years, diatoms have drawn more and more attentions as they may serve as biodiesel producers. Aquatic Species Program has chosen 50 diatom species from 3000 species as the candidates of biodiesel producers in 1998, considering the characteristics like fast growth, rich in lipidcontent, tolerance to stress condition and well performance in large-scale cultivation. The wholegenome sequence ofThalassiosira pseudonanaandPhaeodactylum tricornutumare available at present, and several more will be sequenced soon (Armbrustet al., 2004; Bowleret al., 2008; Courchesneet al., 2009).

Eurythermal and euryhalineCylindrotheca closterium(Caiet al., 2007) belongs to family Bacillariaceae, order Bacillariales, class Bacillariophyceae and phylum Bacillariophyta. It mainly distributes in the intertidal flats, can be cultured and harvested easily and resists to pollution (Lianget al., 2000), and is rich in PUFA (Lianget al., 1999; Lanet al., 2012). It is worthy to purify this diatom (Lin, 2000) and culture it axenically (Linet al., 2000). In this study, we purified a strain of this alga and cultured it axenically, aiming to offer an applicable strain for future large scale culture.

2 Methods

2.1 Algal Purification and Identification

A mixture of diatoms was obtained from The Microalgae Library of Ocean University of China. The mixture was cultured inf/2seawater medium at (22 ± 1)℃, salinity 30 and 70 μmol photons s-1m-2with a rhythm of 12 h light and 12 h dark. The diatom was isolated with algal colony selection and continuous dilution methods as described early (Mcmanus and Katz, 2009). Morphological images were created under an optical microscope (Nikon E 50i)and a scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-840). Universal primers, 18S rRNA (5’-AAC CCC TGG TTG ATC CTG CCA GT-3’ and 5’-GAT CCT TCC GCA GGT TCA CCT AC-3’, andrbcLgene, 5’-TCA GAA CGG ACT CGA ATA AA-3’ and 5’-CCA ATA GTA CCA CCA AAT-3’, were used to amplifying the genomic DNA of the diatom with expected products of about 1200 bp and 1070 bp in length, respectively. PCR was carried out in a volume of 50 μL containing 2.0 UTaqDNA polymerase, 10 nmol dNTP (each), 1nmol primer each, 1×buffer and 2.5 ng template DNA. The nested PCR was performed by denaturing at 94℃ for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturing at 94℃ for 30 s, annealing at 55℃ for 30 s, and extending at 72℃ for 2 min. The PCR product was sequenced commercially with ABI3730 sequencer. The sequences were also deposited into NCBI databank with accession number KC899347 and KC899348. The sequences were aligned with those retrieved from GenBank with ClustalX 1.81 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), and the phylogenetic trees were constructed with MEGA4 (http://www.megasoftware.net/).

2.2 Determination of Antibiotics Sensitivity

Ampicillin, neomycin and chloramphenicol were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Co., Ltd. with their stock solutions prepared following standard protocol (Sambrooket al., 1987). Fifty milliliters off/2medium containing different concentrations of ampicillin (0, 300, 500, 800, 1000 μg mL-1each) or neomycin (0, 50, 100, 300, 500 μg mL-1each) or chloramphenicol (0, 10, 50, 100, 150 μg mL-1each) were used to culture the diatom (initial cell density 106cells mL-1) to either plateau growth phase (ampicillin and neomycin ) or exponential growth phase (chloramphenicol) with OD680value read every 2 days (starting from day 1).

2.3 Determination of Growth, Total Lipid Content and Fatty Acid Composition

The algal cells at the end of exponential growth phase were collected with centrifugation at 6000 g and 20℃, dried with a vacuum freeze drier at 0.03 atm and -50℃for 12 h, and then were accurately weighed to determine the biomass. The specific growth rate was calculated to measure the growth of algal cells at exponential growth phase (Jiaoet al., 2011). About 50 mg of algal biomass was used to determine the total lipid content with gravimetric method (Bligh and Dyer, 1959). Then lipid productivity was calculated from the biomass and total lipid content (Su and Yu, 2013). About 30 mg of dry algae were used to extract fatty acids with the method described early (Volkmanet al., 1989) and the fatty acids content was analyzed with gas chromatography (HP5890E).

3 Results

3.1 Algal Purification and Identification

Algal colonies appeared on solidf/2medium in about 25 days. A colony was inoculated into a well of a 96-well plate with cells in this well diluted step by step by removing 1 μL medium from one well to the other. In about two weeks, pure diatom cultures were obtained from the last dilution with growing alga. Among colonies purified, one was further morphologically characterized and phylogenetically analyzed.

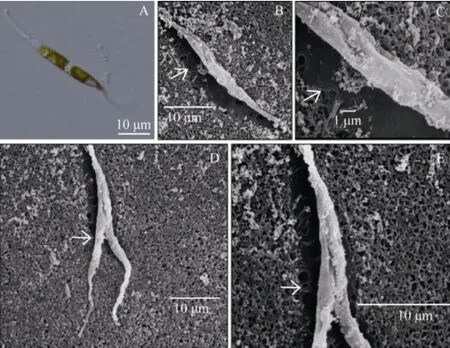

The purified alga was about 50 μm in length, needlelike and thin in shape. Two ends of the cell extended far from the center of the cell (Fig.1A). The chromatophore of the purified alga was in the middle of the cell. Under scanning electric microscope, the cell was found to be wrapped by the raphe canal of valves (Figs.1B and C), which is a typical characteristic ofCylindrotheca closterium. The algal cell moved around when water streamed through the raphe canal, and divided longitudinally along the raphe canal (Figs.1D, E). Thus, the purified alga may be identified toCylindrothecasp. morphologically.

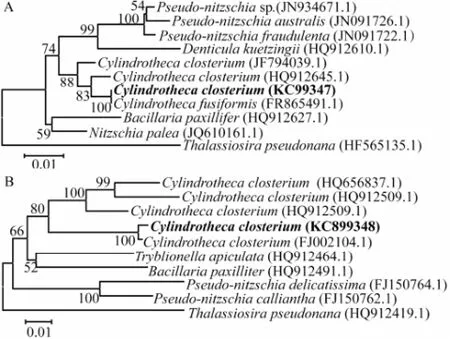

The phylogenetic tree of 18S rRNA andrbcLgene amplified from the purified alga showed that it was closer toC. closteriumthan to other species; it was 99% and 100%similar toC. closteriumin 18S rRNA andrbcLgene sequence (Figs.2A and B), respectively. Therefore, the strain was identified toC. closterium.

Fig.1 Morphological characteristics of the diatom purified in this study. A, under optical microscope; B and C, under scanning electric microscope, white arrow points to raphe canal running through the whole cell; D and E, under scanning electric microscope, white arrow points to the dividing position.

Fig.2 Phylogenetic tree of 18S rRNA (A) andrbcL(B) gene of diatom constructed with neighbor-joining method.

3.2 Antibiotics Sensitivity ofC. closterium

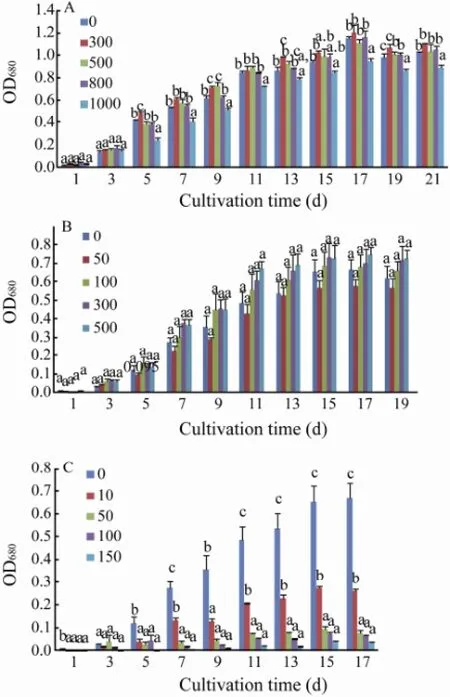

Fig.3 Effect of ampicillin (A), neomycin (B) and chloramphenicol (C) on the growth ofC. closterium.

As showed in Fig.3, ampicillin at a concentration range from 300 to 800 μg mL-1enhanced the growth ofC. closterium. Ampicillin at 1000 μg mL-1significantly affected the growth ofC. closterium. Little effect of neomycin on the growth ofC. closteriumwas observed. Chloramphenicol at concentrations higher than 10 μg mL-1significantly inhibited the growth ofC. closterium. When the concentration of chloramphenicol was higher than 50 μg mL-1, the growth ofC. closteriumwas completely inhibited. So the purified alga was resistant to ampicillin and neomycin but sensitive to chloramphenicol.

3.3 Growth, Total Lipid Content and Fatty Acid Composition

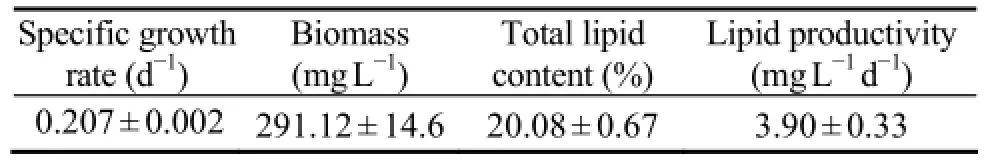

The specific growth rate ofC. closteriumwas 0.207 ± 0.002 (d-1), reaching a biomass density of 291.12 ± 14.6 mg L-1. Its total lipid accounted for 20.08% ± 0.67% of dry weight (Table 1). Saturated fatty acids accounted for 40.9%-42.3% of the total fatty acid. The amount of 16:0 was the most abundant, reaching 29.90% ± 0.33% of the total fatty acids. Monounsaturated fatty acids accounted for 37.17%-38.37% of the total. The most abundant fatty acid was 16:1 (n-7), which accounted for 34.28% ± 0.48% of the total. Polyunsaturated fatty acids consisted of 19.96%-20% of the total fatty acids and the most abundant two were EPA and arachidonic acid. The combined amount of 16:0 and 16:1 (n-7) was as high as 64% of the total, indicating that the alga was suitable for biodiesel production (Table 2). EPA and arachidonic acid are excellent antioxidants and nutrition additives. The purified alga may serve as EPA and arachidonic acid producer as well.

Table 1 Growth, lipid content and lipid productivity ofC. closterium

Table 2 Fatty acid composition ofC. closterium

4 Discussion

The dominating fatty acids of diatoms are 14:0, 16:0, 16:1 (n-7) and EPA, which all together account for 68.7% of the total fatty acid (Dunstanet al., 1993). In this study, we found that the combined amount of 16:0 and 16:1 (n-7)ofC. closteriumwas as high as 64% of the total.C. closteriumwas obviously different fromC. fusiformisin morphology; however, it was only a single base different fromC. fusiformisin 18s rRNA gene. Under a similar condition, the specific growth rate of the alga was much higher than that ofPhaeodactylum tricornutum(Liuet al., 2008); however, its lipid content and lipid productivity were lower than most of the biodiesel producing candidates (Konget al., 2010; Yanget al., 2011). Fortunately, chemical and physical mutation (Nečas, 1975; Niwaet al., 2009) and genetic modification may modify this alga to a highly efficient lipid producer. TheC. closteriumpurified and characterized in this study was insensitive to ampicillin and neomycin but sensitive to chloramphenicol; thus ampicillin and neomycin may be applied to its axenical culture while chloramphenicol may serve as the selection marker in its genetic modification. We found thatC. closteriumsinks to the bottom of flask in only a few minutes without aeration. All these characteristics make this alga a biodiesel-producing candidate.

Growth rate, lipid content and fatty acid composition can be greatly influenced by culturing conditions. For example, nitrogen starvation has been widely applied in increasing lipid content and TAG production in a wide range of microalgal species (Widjajaet al., 2009). In addition, temperature and salinity may influence algal fatty acid composition. Eurythermal and euryhalineC. closteriummainly inhabits intertidal zone and is often directly exposed to sunlight, implying its high tolerance to high irradiation, temperature and salinity. It has been found thatC. closteriumremains metabolic activity with no statistically significant change in sensitivity to copper when illumination and temperature drastically change (Araujoet al., 2008). Therefore,C. closteriummay be genetically improved to become a desirable oil producer.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (2011CB200901) and National Technical Supporting Project Foundation (2011BAD14B01) and Energy Project from State Bureau of Oceanic Administration (Grant No. GHME2011SW03).

Araujo, C. V. M., Diz, F. R., Moreno-Garrido, I., Lubian, L. M., and Blasco, J., 2008. Effects of cold-dark storage on growth ofCylindrotheca closteriumand its sensitivity to copper.Chemosphere, 72 (9): 1366-1372.

Armbrust, E. V., Berges, J. A., Bowler, C., Green, B. R., Martinez, D., Putnam, N. H., Zhou, S. G., Allen, A. E., Apt, K. E., Bechner, M., Brzezinski, M. A., Chaal, B. K., Chiovitti, A., Davis, A. K., Demarest, M. S., Detter, J. C., Glavina, T., Goodstein, D., Hadi, M. Z., Hellsten, U., Hildebrand, M., Jenkins, B. D., Jurka, J., Kapitonov, V. V., Kröger, N., Laul, W. W. Y., Lane, T. W., Larimer, F. W., Lippmeier, J. C., Lucas, S., Medina, M., Montsant, A., Obornik, M., Parker, M. S., Palenik, B., Pazour, G. J., Richardson, P. M., Rynearson, T. A., Saito, M. A., Schwartz, D. C., Thamatrakoln, K., Valentin, K., Vardi, A., Wilkerson, F. P., and Rokhsar, D. S., 2004. The genome of the diatomThalassiosira pseudonana: Ecology, evolution and metabolism.Science, 306 (5693): 79-86.

Bligh, E. G., and Dyer, W. J., 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification.Canada Journal of Biochemistry Physiology, 37: 911-917.

Bowler, C., Allen, A. E., Badger, J. H., Grimwood, J., Jabbari, K., Kuo, A., Maheswari, U., Martens, C., Maumus, F., Otillar, R. P., Rayko, E., Salamov, A., Vandepoele, K., Beszteri, B., Gruber, A., Heijde, M., Katinka, M., Mock, T., Valentin, K., Verret, F., Berges, J. A., Brownlee, C., Cadoret, J. P., Chiovitti, A., Choi, C. J., Coesel, S., De Martino, A., Detter, J. C., Durkin, C., Falciatore, A., Fournet, J., Haruta, M., Huysman, M. J., Jenkins, B. D., Jiroutova, K., Jorgensen, R. E., Joubert, Y., Kaplan, A., Kröger, N., Kroth, P. G., La Roche, J., Lindquist, E., Lommer, M., Martin-Jézéquel, V., Lopez, P. J., Lucas, S., Mangogna, M., McGinnis, K., Medlin, L. K., Montsant, A., Oudot-Le Secq, M. P., Napoli, C., Obornik, M., Parker, M. S., Petit, J. L., Porcel, B. M., Poulsen, N., Robison, M., Rychlewski, L., Rynearson, T. A., Schmutz, J., Shapiro, H., Siaut, M., Stanley, M., Sussman, M. R., Taylor, A. R., Vardi, A., von Dassow, P., Vyverman, W., Willis, A., Wyrwicz, L. S., Rokhsar, D. S., Weissenbach, J., Armbrust, E. V., Green, B. R., Van de Peer, Y., and Grigoriev, I. V., 2008. ThePhaeodactylumgenome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes.Nature, 456 (7219): 239-244.

Cai, Q. Y., Du, Q., Qian, X. M., and Xu, C. Y., 2007. Comprehensive evaluation on marine ecological environment of Sansha Bay in Fujian, China.Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 29 (2): 156-160 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Courchesne, N. M. D., Parisien, A., Wang, B., and Lan, C. Q., 2009. Enhancement of lipid production using biochemical, genetic and transcription factor engineering approaches.Journal of Biotechnology, 142 (1-2): 31-41.

Dunstan, G. A., Volkman, J. K., Barrett, S. M., Leroi, J. M., and Jeffrey, S. W., 1993. Essential polyunsaturated fatty acids from 14 species of diatom (Bacillariaceae).Phytochemishtry, 35 (1): 155-161.

Field, C. B., Behrenfeld, M. J., Randerson, J. T., and Falkowski, P., 2003. Primary production of the biosphere, integrating terrestrial and oceanic components.Science, 281 (5374): 237-240.

Green, M, R., and Sambrook, J., 2012.Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, N.Y., 2028pp.

Ignacio, M. G., Lubián, L. M., Jiménez, B., Soares, A. M. V. M., and Blasco, J., 2007. Estuarine sediment toxicity tests on diatoms: Sensitivity comparison for three species.Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 71 (1-2): 278-286.

Jiao, Y. Y., Yu, J. Z., and Pan, K. H., 2011. Effects of indole-3-acetic acid the growth and fatty acid composition ofNannochloropsis oculata.Journal of Ocean University of China. 41 (4): 57-60 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Kong, W. B., Hua, S. F., Song, H., and Xia, C. G., 2010. Production on biodiesel using microalgae.China Oils and Fats, 35 (8): 51-55 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Lan, L., Wang, Q. A., He, Y., Liu, Y., and Gong, Q. L., 2012. Analysis of nutritional components ofCylindrotheca fusiformisunder fed-batch-continuous culture.Journal of Ocean University of China, 42 (6): 68-71 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Lebeau, T., and Robert, J. M., 2003. Diatom cultivation and biotechnologically relevant products. Part 1: Cultivation at various scales.Applied Microbiology Biotechnology, 60 (6):624-632.

Liang, Y., Mai, K. S., Sun, S. C., and Zhan, D. M., 1999. Fatty acid composition and total lipid content of 33 strains in the genusCylindrotheca.Journal of Ocean University of Qingdao, 29: 457-462 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liang, Y., Mai, K. S., Sun, S. C., Zhou, H. C., and Pan, J. H., 2000. Effects of different media on the growth and the composition of fatty acids ofCylindrotheca fusiformis.Transactions of Oceanology and Limnology, 1: 60-67 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Lin, W., 2000. Axenization of several marine microalga cultures.Experiment and Technology, 24 (10): 3-5 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Lin, W., Chen, D., and Liu, X., 2000. Marine microalgal axenation and comparison of growth characteristics between natural and axenic marine microalgae.Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 31 (6): 647-652 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, X. J., Duan, S. S., and Li, A. F., 2008. Effects of organic carbon source on growth, biochemical components and fatty acid composition ofPhaeodactylum tricornutum. Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 24 (1): 147-152 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Mann, D. G., 1989. The species concept in diatoms: Evidence morphologically distinct sympatric gamodemes in four epipelic species.Plant Systematics and Evolution, 164 (1-4): 215-237.

Mcmanus, G. B., and Katz, L. A., 2009. Molecular and morphological methods for identifying plankton: What makes a successful marriage?Journal of Plankton Research, 31 (10):1119-1129.

Nečas, J., 1975. Physiological and mutagenic effects of N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in populations of chlorococcal algae.Biologia Plantarum, 17 (2): 130-138.

Niwa, K., Hayashi, Y., Abe, T., and Aruga, Y., 2009. Induction and isolation of pigmentation mutants ofPorphyra yezoensis(Bangiales, Rhodophyta) by heavy-ion beam irradiationpre.Phycological Research, 57 (3): 194-202.

Su, Z. L., and Yu, Y., 2013. Recent study on increasing oil production yield of biodiesel.Shandong Chemical Industry, 42 (1): 33-35 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Tréguer, P., Nelson, D. M., van Bennekom, A. J., DeMaster, D. J., Leynaert, A., and Queguiner, B., 1995. The silica balance in the world ocean: A reestimate.Science, 268 (5209): 375-379.

Volkman, J. K., Jeffrey, S. W., Nichols, P. D., Rogers, G. I., and Garland, C. D., 1989. Fatty acid and lipid composition of 10 species of microalgae used in mariculture.Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 128 (3): 219-240.

Wang, H. Y., and Zeng, X. B., 2007. Composition of polyunsaturated fatty acids produced by three strains of diatoms.China Oils and Fats, 32 (7): 76-78 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Widjaja, A., Chien, C. C., and Ju, Y. H., 2009. Study of increasing lipid production from fresh water microalgaeChlorella vulgaris.Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 40 (1): 13-20.

Xu, J., Wang, G. Z., and Wu, L. S., 2012. Effects of planktonic diatoms on the survival, development and reproduction of a benthic copepod Tigriopusjaponicus.Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 51 (5): 939-943 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yang, J., Jiang, J. C., and Zhang, N., 2011. Oil productivity capabilities of several microalgae strains in different cultivation methods.Biomass Chemical Engineering, 45 (2): 15-19 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(Edited by Qiu Yantao)

(Received May 21, 2013; revised September 30, 2013; accepted December 23, 2014)

© Ocean University of China, Science Press and Spring-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015

* Corresponding author. Tel: 0086-532-82031939 E-mail: khpan@ouc.edu.cn

杂志排行

Journal of Ocean University of China的其它文章

- Impacts of the Two Types of El Niño on Pacific Tropical Cyclone Activity

- Numerical Simulation of Typhoon Muifa (2011) Using a Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere-Wave-Sediment Transport (COAWST) Modeling System

- Estimating the Turbulence Characteristics in the Bottom Boundary Layer of Monterey Canyon

- Composition and Origin of Ferromanganese Crusts from Equatorial Western Pacific Seamounts

- Hydroelastic Analysis of a Very Large Floating Structure Edged with a Pair of Submerged Horizontal Plates

- A Storm Surge Intensity Classification Based on Extreme Water Level and Concomitant Wave Height