肺癌患者唾液中细菌构成分析

2015-03-09俞小卫杨明夏郑建洲高瑞辰

俞小卫, 杨明夏, 郑建洲, 高瑞辰,

贺 琛1, 鄢新民2, 庞 胜2

(1. 江苏省常州市第二人民医院 呼吸科, 江苏 常州, 213003; 2. 美国加州大学洛杉矶分校医学院)

肺癌患者唾液中细菌构成分析

俞小卫1, 杨明夏1, 郑建洲1, 高瑞辰1,

贺琛1, 鄢新民2, 庞胜2

(1. 江苏省常州市第二人民医院 呼吸科, 江苏 常州, 213003; 2. 美国加州大学洛杉矶分校医学院)

摘要:目的探讨唾液中细菌构成与肺癌的关系。方法收集鳞癌和腺癌以及非肿瘤对照组唾液标本,每组10例。对唾液中大量的16 s rDNA进行测序分析。结果经定量PCR(qPCR)证实,5个细菌集群在癌症和对照组样本间有显著差异。结论16 s测序和PCR相结合的研究显示,有两个细菌属(二氧化碳噬纤维菌属和韦永氏球菌属)水平癌症组要显著高于非癌症组。

关键词:肺癌; 16 s rDNA测序; 二氧化碳噬纤维菌属; 韦永氏球菌属; 唾液微生物群

肺癌5年存活率约11%[1],在北美和全球范围是癌症相关死亡最常见原因[2-3]。吸烟被认为是肺癌的一个重要病因,原因是烟草中含有可能会诱发细胞转换的致癌物质[4]。然而,有报告表明肺癌涉及免疫应答[5]、病毒性感染[6]以及其他与烟草不相关的因素[6-7]。最近的研究[8-13]报告唾液菌群与几种癌症有关。先前的报道[14-15]表明衣原体感染与肺癌有关。大多数唾液细菌来自口腔,有些也可能来自食道和上呼吸道。口腔里的细菌生存和发展依赖于口腔环境,而口腔环境可以受到饮食、蛋白质或唾液中其他营养物质、痰液的成分以及习惯譬如吸烟的影响。这些因素与肺癌的发生和发展有关。基于这些考虑,以及之前报道的细菌参与肺癌中肿瘤发生[14-16], 作者调查了肺癌患者的唾液细菌水平。作者使用Illumina公司HiSeq 2000, 通过测序16 s rDNA的V3和V6来量化肺癌和对照组唾液样本中菌群组成。这种方法可以识别超过500种流行的人类细菌种类和高达每样本100 000细菌序列。这种高灵敏度和综合分析提供一种新的方法来研究肺癌和细菌组成之间的关系。

非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)在肺癌中所占比例超过80%,其中绝大多数是鳞状细胞癌(SCC, 30%~35%)或腺癌(AC~50%)。在第一轮的研究中,作者选择鳞癌或腺癌患者和非肿瘤对照组,每组10个样本,确定了能证明肺癌患者和非肿瘤对照组之间存在显著差异的细菌纲/属。随后作者使用qPCR量化丰富的细菌群证实了这些结果。在第二轮的研究中,所选的细菌集群被用来研究新的一群患者样本,进一步评估这些细菌集群和肺癌之间的关系。

1材料与方法

1.1 唾液样本收集

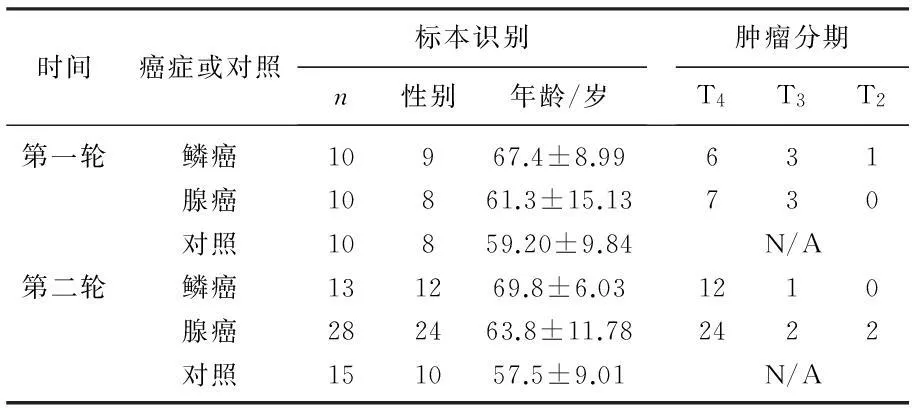

唾液样本收集是根据常州第二人民医院(CSPH)伦理委员会批准的协议。所有对象的招募皆来自常州市第二人民医院。因为吸烟可能影响口腔里细菌的增长,只有有着10年以上吸烟史的受试者被选择。唾液样本采集是在癌症诊断之后和治疗之前。没有一个对象,包括病人和对照者,证明有与唾液细菌相关的其他疾病,譬如糖尿病、免疫功能紊乱、疱疹病毒感染、口腔黏膜溃疡。患者信息见表1。

表1 肺癌和非癌症对照组唾液样本比较

年龄在两癌症组间及每癌症组与对照组间无显著差异。

1.2 唾液样本菌群的测序分析

唾液中DNA含量通过SDS溶菌、苯酚萃取去除唾液中蛋白质后被分离。乙醇沉淀恢复样本中的DNA,其含量通过PCR扩增,正如前面所描述的[17]。作者利用IlluminaHiSeq2000对扩增的样本进行测序,并对16 s rDNA的V3和V6 进行分析。为确保高质量的数据,作者采用严格的条件来处理样本序列,并因此能够产生有效的结果。按以下操作步骤进行: ① 所有读数通过允许一个不匹配的样本条形码和两个不匹配相邻PCR引物被分配给对应的样本; ② 读数随后通过PyroNoise算法消除干扰[18]; ③ 读数包含模糊的核苷酸或一个被移除超过8个碱基对(bp)的均聚物,是序列短于200个bp或超过1 000个bp; ④ 这些读数使用最近的空间终止对齐方式对齐(NAST),基于序列同步自定义,基于席尔瓦对齐参考[19], 并将没有预期的对齐参考比对区域的序列丢弃; ⑤ 通过UCHIME算法确定的嵌合序列被移除[20]; ⑥ 读数通过贝叶斯分类法和核糖体数据库项目(RDP)进行分类。线粒体序列或未知(这些数据不能在国家级水平上分类)被移除。最后,所有有效的读数聚集到操作分类单位(OTUs),基于97%序列相似性,使用MOTHUR程序[21]。样本在不同分类水平的分类分析(门、纲、目、科、属)通过使用QIIME被创建[22]。任何指定的纲/属的水平被算作序列获得总额的百分比。

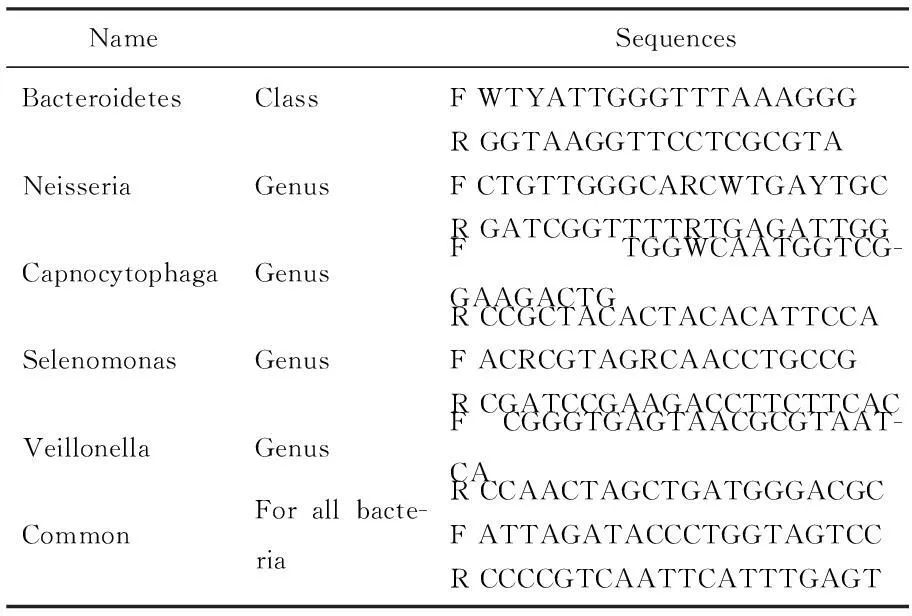

定量聚合酶链反应:从发现阶段细菌测序所确定细菌集群将被qPCR进一步检测。具体检测16 s rDNA PCR引物的设计(表2)。引物是选择从先前出版的文献[23]或通过搜索RDP数据库。

表2 16S rDNA定量PCR引物

用于qPCR寡核苷酸引物: F, forward PCR primers;

R, reverse PCR primers。

1.3 统计血分析

根据已发表的文献[24-29],作者使用接收机操作特征(ROC)曲线分析,这是MedCalc提供的软件包(MedCalc Software, Acacialaan 22, B-8400 Ostend, Belgium)。为了更好的呈现数据,线的颜色和厚度和字体的大小修改。

2结果

2.1 肺癌患者与非肿瘤对照组间不同唾液微生物剖面图

基于作者的测序结果,一个类杆菌纲和4个细菌属(奈瑟氏菌属, 二氧化碳噬纤维菌属, 月形单胞菌属和韦永氏球菌属)在肿瘤和非肿瘤病人之间具有显著差异(P<0.05)。类杆菌属和奈瑟氏菌属在癌症患者的水平低于非肿瘤对照组,而二氧化碳噬纤维菌属, 月形单胞菌属和韦永氏球菌属水平高于非肿瘤对照组。

2.2 细菌定量PCR检测

作者采用qPCR来量化所选择细菌纲/属的水平。利用可以扩增大多数细菌16 s rDNA 一对PCR引物标准化癌症和对照组rDNA水平。qPCR结果与测序结果比较,癌症样本的qPCR显示二氧化碳噬纤维菌属和韦永氏球菌属的水平显著增高,而类杆菌属和奈瑟氏菌属水平较低, 支持使用qPCR量化所选择细菌集群水平的可行性。月形单胞菌属的水平在一些标本中没有被检测到,所以作者从进一步qPCR研究剔除了这个细菌生物标志物。qPCR的总体结果跟测序研究结果类似。

经16 s rDNA定量PCR而确定。因此, 作者反复qPCR来评估实验之间的变化,每组包含20个数据点(样标100倍)

2.3 利用所选择细菌生物标志物对标本量化

评估选择的细菌集群,作者使用qPCR量化附加的样本,包括41个癌症样本(13 SCC,28 AC)和15个非肿瘤对照。作者使用qPCR量化类杆菌属和奈瑟氏菌属、二氧化碳噬纤维菌属、韦永氏球菌属水平。这些附加的样本的结果表明二氧化碳噬纤维菌属和韦永氏球菌属癌症患者的鳞癌和腺癌亚型水平显著增高,与作者先前30例样本分析一致。

然而,类杆菌属和奈瑟氏菌属 并没有象在第一轮研究中 那么显著增高。虽然在非癌症对照组中奈瑟氏菌属的水平明显高于那些腺癌患者,ROC曲线下面积(AUC)值为0.77, 但非肿瘤对照组跟鳞癌比较没有显著差异,AUC低于0.70。对于类杆菌属,通过比较鳞状细胞癌、腺癌患者与非肿瘤患者样本所获得的AUC值小于0.70, 提示二氧化碳噬纤维菌属和韦永氏球菌属与肺癌有关,而类杆菌属和奈瑟氏菌属可能需要更多的研究来说明这两个细菌集群是否与肺癌有关。

3讨论

作者集中的测序证明类杆菌属和四个菌属(奈瑟氏菌属, 二氧化碳噬纤维菌属, 月形单胞菌属和韦永氏球菌属)水平肺癌和非肿瘤对照样本中显著不同。基于这些结果,作者进行第二轮的研究,这些结果表明,至少五个细菌集群中有二个, 二氧化碳噬纤维菌属和韦永氏球菌属,其水平癌症患者的唾液样本显著高于非癌症的对照组。

唾液微生物群与肺癌之间的内在关系正处在调查中。细菌产生的毒素可以干扰细胞周期,从而改变细胞生长[15, 30-31]。这是由于改变的基因控制正常细胞分裂和凋亡[32-33]。对肺癌特定细菌群水平较高的另一种解释是与肺癌相关的饮食可能会偏爱一些细菌,而抑制一些其他细菌。因此,唾液中细菌组成的模式可能间接与肺癌有关。正如前面报道的,大豆和茶抑制肺癌的风险[34-36]和癌症进展[37], 而红肉会增加肺癌的风险[38], 提示饮食与肺癌的发生有关。

由于饮食也与口腔细菌组成有关[39],菌群在一定程度上可能反映肺癌的风险。唾液微生物群也可能通过诱导长期免疫反应影响肺部细胞。众所周知,肠道微生物群由于免疫耐受的破坏参与炎症性肠病(IBD)的发病机制[40]。

作者注意到鳞癌和腺癌之间有着不同。鳞癌样本中韦永氏球菌属水平要高于腺癌样本中(图1 e、2 d、3 d),当与非癌症对照组样本比较,证明存在显著的差异。小韦荣氏球菌是从肺癌患者下呼吸道分离出来的细菌,提示这一属跟肺癌有关[41]。然而,这一属在肺癌发生发展的发生中精确的作用还不清楚。

二氧化碳噬纤维菌种通常在口咽道发现,该菌种已报道参与肺癌,因为他们已经被证明参与肺脓肿形成[42]和下呼吸道感染[43],表明癌症增长偏爱这些细菌的生长。Neisseria在癌症患者被发现其水平显著低于二氧化碳噬纤维菌属和韦永氏球菌属。胰腺癌样本中也发现了相似的结果[12],表明奈瑟氏菌属可以抑制癌细胞。一个众所周知的例子是使用卡介苗(BCG)对膀胱癌治疗[44]。

关于吸烟,所有的受试者在这项研究中已经抽了10年了。尽管患者集中的一个城市,超过一半的人从许多不同的地方搬到常州。因此,作者认为在此描述的细菌集群是全球分布的。然而,正如前面所报道的,唾液细菌也与饮食有关[39], 因为来自不同地区的人有着不同的饮食,有必要扩大研究来说明不同种族,宗教,或饮食限制中饮食所产生的影响。

参考文献

[1]Verdecchia A, Francisci S, Brenner H, et al. Recent cancer survival in Europe: a 2000-02 period analysis of EUROCARE-4 data[J]. The lancet oncology, 2007, 8(9): 784.

[2]Jemal A, Bray F, Center M M, et al. Global cancer statistics[J]. A cancer journal for clinicians, 2011, 61(2): 69.

[3]Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths[J]. A cancer journal for clinicians, 2011, 61(4): 212.

[4]Hecht S S. Lung carcinogenesis by tobacco smoke[J]. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer, 2012, 131(12): 2724.

[5]Pine S R, Mechanic L E, Enewold L, et al. Increased levels of circulating interleukin 6, interleukin 8, C-reactive protein, and risk of lung cancer[J]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2011, 103(14): 1112.

[6]Samet J M, Avila-Tang E, Boffetta P, et al. Lung cancer in never smokers: clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors[J]. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 2009, 15(18): 5626.

[7]Yang P. Lung cancer in never smokers[J]. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine, 2011, 32(1): 10.

[8]Gorugantula L M, Rees T, Plemons J, et al. Salivary basic fibroblast growth factor in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma or oral lichen planus[J]. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology, 2012, 114(2): 215.

[9]Elashoff D, Zhou H, Reiss J, et al. Prevalidation of salivary biomarkers for oral cancer detection[J]. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2012, 21(4): 664.

[10]Turner D O, Williams-Cocks S J, Bullen R, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) screening and detection in healthy patient saliva samples: a pilot study[J]. BMC oral health, 2011, 11: 28.

[11]Zhang L, Xiao H, Zhou H, et al. Development of transcriptomic biomarker signature in human saliva to detect lung cancer[J]. Cellular and molecular life sciences, 2012, 69(19): 3341.

[12]Farrell J J, Zhang L, Zhou H, et al. Variations of oral microbiota are associated with pancreatic diseases including pancreatic cancer[J]. Gut, 2012, 61(4): 582.

[13]Byakodi R, Krishnappa R, Keluskar V, et al. The microbial flora associated with oral carcinomas[J]. Quintessence Int, 2011, 42(9): e118.

[14]Laurila A L, Anttila T, Laara E, et al. Serological evidence of an association between Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and lung cancer[J]. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer, 1997, 74(1): 31.

[15]Littman A J, White E, Jackson L A, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and risk of lung cancer[J]. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2004, 13(10): 1624.

[16]Moghaddam S J, Ochoa C E, Sethi S, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer[J]. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2011, 6: 113.

[17]Paster B J, Boches S K, Galvin J L, et al. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque[J]. Journal of bacteriology, 2001, 183(12): 3770.

[18]Quince C, Lanzen A, Curtis TP, et al. Accurate determination of microbial diversity from 454 pyrosequencing data[J]. Nature methods, 2009, 6(9): 639.

[19]Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB[J]. Nucleic acids research, 2007, 35(21): 7188.

[20]Edgar R C, Haas B J, Clemente J C, et al. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection[J]. Bioinformatics, 2011, 27(16): 2194.

[21]Schloss P D, Westcott S L, Ryabin T, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities[J]. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2009, 75(23): 7537.

[22]Caporaso J G, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data[J]. Nature methods, 2010, 7(5): 335.

[23]Muhling M, Woolven-Allen J, Murrell J C. Joint I: Improved group-specific PCR primers for denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of the genetic diversity of complex microbial communities[J]. The ISME journal, 2008, 2(4): 379.

[24]DeLong E R, DeLong D M, Clarke-Pearson D L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach[J]. Biometrics, 1988, 44(3): 837.

[25]Griner P F, Mayewski R J, Mushlin A I, et al. Selection and interpretation of diagnostic tests and procedures. Principles and applications[J]. Annals of internal medicine, 1981, 94(4 Pt 2): 557.

[26]Hanley J A, Hajian-Tilaki K O. Sampling variability of nonparametric estimates of the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves: an update[J]. Academic radiology, 1997, 4(1): 49.

[27]Hilgers R A. Distribution-free confidence bounds for ROC curves[J]. Methods of information in medicine, 1991, 30(2): 96.

[28]Metz C E. Basic principles of ROC analysis[J]. Seminars in nuclear medicine, 1978, 8(4): 283.

[29]Zweig M H, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine[J]. Clinical chemistry, 1993, 39(4): 561.

[30]Koyi H, Branden E, Gnarpe J, et al. An association between chronic infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae and lung cancer. A prospective 2-year study[J]. APMIS: acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica, 2001, 109(9): 572.

[31]Kocazeybek B. Chronic Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection in lung cancer, a risk factor: a case-control study[J]. Journal of medical microbiology, 2003, 52(Pt 8): 721.

[32]Lara-Tejero M, Galan J E. A bacterial toxin that controls cell cycle progression as a deoxyribonuclease I-like protein[J]. Science, 2000, 290(5490): 354.

[33]Nougayrede J P, Taieb F, De Rycke J, et al. Cyclomodulins: bacterial effectors that modulate the eukaryotic cell cycle[J]. Trends in microbiology, 2005, 13(3): 103.

[34]Seow A, Poh W T, Teh M, et al. Diet, reproductive factors and lung cancer risk among Chinese women in Singapore: evidence for a protective effect of soy in nonsmokers[J]. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer, 2002, 97(3): 365.

[35]Matsuo K, Hiraki A, Ito H, et al. Soy consumption reduces the risk of non-small-cell lung cancers with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations among Japanese[J]. Cancer science, 2008, 99(6): 1202.

[36]Arts I C. A review of the epidemiological evidence on tea, flavonoids, and lung cancer[J]. The Journal of nutrition, 2008, 138(8): 1561S.

[37]Gallo D, Zannoni G F, De Stefano I, et al. Soy phytochemicals decrease nonsmall cell lung cancer growth in female athymic mice[J]. The Journal of nutrition, 2008, 138(7): 1360.

[38]Lam T K, Cross A J, Consonni D, et al. Intakes of red meat, processed meat, and meat mutagens increase lung cancer risk[J]. Cancer research, 2009, 69(3): 932.

[39]Adler C J, Dobney K, Weyrich L S, et al. Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions[J]. Nature genetics, 2013, 45(4): 450.

[40]Fava F, Danese S. Intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: friend of foe[J]. World journal of gastroenterology, 2011, 17(5): 557.

[41]Rybojad P, Los R, Sawicki M, et al. Anaerobic bacteria colonizing the lower airways in lung cancer patients[J]. Folia histochemica et cytobiologica/Polish Academy of Sciences, Polish Histochemical and Cytochemical Society, 2011, 49(2): 263.

[42]Thirumala R, Rappo U, Babady N E, et al. Capnocytophaga lung abscess in a patient with metastatic neuroendocrine tumor[J]. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2012, 50(1): 204.

[43]Forman M A, Johnson L R, Jang S, et al. Lower respiratory tract infection due to Capnocytophaga cynodegmi in a cat with pulmonary carcinoma[J]. Journal of feline medicine and surgery, 2005, 7(4): 227.

Analysis in saliva bacterial composition

in patients with lung cancer

YU Xiaowei1, YANG Mingxia1, ZHENG Jianzhou1, GAO Ruichen1,

HE Chen1, YAN Xinmin2, PANG Shen2

(1.DepartmentofRespiratory,ChangzhouSecondPeople′sHospital,Changzhou,Jiangsu, 213003;

2.DepartmentofOrthopaedicSurgeryandtheOrthopaedicHospitalResearchCenter,

DavidGeffenSchoolofMedicineatUniversityofCalifornia,LosAngeles,USA, 90095)

ABSTRACT:ObjectiveTo investigate the relationship between saliva bacteria composition and lung cancer. MethodsSalivary samples were collected in squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and normal people without tumors, 10 cases for each group. Extensive 16S rDNA sequencing was analyzed. ResultsBy quantitative PCR (qPCR), there were significant differences between five bacterial clusters and control samples. ConclusionThe combination of the 16S sequencing study and the PCR study reveal that the levels of two bacterial genera (capnocytophaga and veillonella) are significantly higher in the saliva samples than those in people without cancer.

KEYWORDS:lung cancer; 16S rDNA sequencing; capnocytophaga; veillonella; saliva microbiota

通信作者:庞胜, E-mail: spang@ucla.edu

基金项目:江苏省常州市中外合作科技基金(CZ20110021)

收稿日期:2014-12-16

中图分类号:R 734.2

文献标志码:A

文章编号:1672-2353(2015)15-029-05

DOI:10.7619/jcmp.201515009