Living Longer, Dying Differently

2015-03-01ByPeterNowak

By Peter Nowak

To a caveman, modern humans might appear not unlike Lestat and his vampire kin.1We don’t necessarily consume blood to live, nor can we transform into bats, wolves, or mist, but we do have a host of seemingly superhuman powers.2Chief among those, to the primitive3human, would be our ability to live long lives.

If a caveman were exceptionally lucky, he might have made it to his 40s, but he more than likely would have succumbed to pneumonia, starvation, or injury before his early 20s—if he survived infancy in the first place, that is.4Life expectancy5for humans more than 10,000 years ago was short and didn’t improve much for a long time. In ancient Rome, the average citizen lived to only about age 24. But most counted themselves fortunate to6get even that far; more than a third of children died before their first birthday. A thousand years later, expectations looked much the

Over the course of the next 800 years, people in the more advanced parts of the world added only 15 years to their life expectancy. An average American in 1820 could expect to see 39. Lifespans started to pick up in the early 19th century—around the same time that vampire myths were proliferating in Europe—and really sped up in the 20th thanks to a decline in infant mortality and improvements to health in general.7By 2010, the average U.S. life expectancy had nearly doubled from two centuries prior, at 78 years, with similar results in other developed countries. To a caveman, or an average Roman, that would seem like an eternity8.

One question that inevitably arises when talking about living longer is, are we living better? A person might live to 100 today, but what’s the quality of those later years?

The question can’t be answered empirically9unless we consider what used to make us sick and kill us. The top three killers of Americans in 1900—pneumonia or influenza, tuberculosis, and gastrointestinal infections—don’t appear on the 2010 list, banished to manageability along with historic illnesses such as smallpox, scurvy, and rubella.10Today’s top three—heart disease, cancer, and noninfectious airways disease11—stand apart. Unlike their predecessors, they’re not infectious; instead they’re environmental, self-inflicted, or genetic.12Some doctors believe that makes them eminently13more treatable. Others think we’re entering a technologydriven healthcare revolution that not only will beat back some of the worst killers but also greatly improve the quality of life after illness.

“远古时期,人类的寿命最多只有四十几岁;而如今人类的寿命已能够达到一百岁以上。但是,寿命的延长有没有伴随着生命质量的提升?生命的价值又将如何体现?一个人的生命,若不知自惜,任寿命再长,也毫无意义。”

《夜访吸血鬼》剧照

Health gadgets and apps are proliferating quickly and comprehensively.14With inexpensive heart-rate monitoring and stepcounting wristbands such as the Nike Fuelband and the Fitbit becoming a hit with consumers in recent years,15inventors and entrepreneurs are flooding the market with all manner of self-tracking tools. Sensoria’s Fitness Socks gauge how well you walk, your individual footfalls and gait, then give you an overall sense of your foot health.16The HapiFork tracks how quickly you eat and chew, and buzzes if you’re going too fast.17No human function activity can’t be tracked, measured, and corrected.

Whether we’re living better is one of the most subjective questions we can ask ourselves since so many factors come into play. Age and era are the biggest. If you had asked a 30-year-old in the 18th century to rate her quality of life, her answer would have differed widely from a similarly aged person living in the developed world right now. Yet a 90-yearold today might feel the same as that 30-year-old three centuries prior. Neither person would have the necessary context to consider the other’s life.

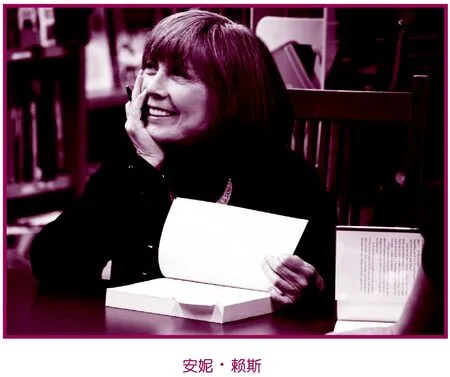

“We’re seeing death in a new way,” says Anne Rice18, the author of Interview with the Vampire. “Instead of taking it for granted, the people I know see it as a personal catastrophe19. I get emails from people who are actually surprised that someone has died. They regard it as an injustice. I understand their feelings, I get it, but this is a fairly new perspective20on death. Nobody in the 1900s would have regarded death as a personal catastrophe. They would have mourned and might have been griefstricken,21but they saw death all around them.”

In that sense, death as an event is increasing in its importance, which conversely22means that the value of human life is also rising. In economics, a commodity is more valuable the rarer it is, which is why a finite resource such as oil can fetch top dollar.23Human life, measured as time on Earth, works the same way—but it also doesn’t. If we can expect to live a long time, we may not treasure individual years as much. We might even waste time by indulging in extraneous pursuits, such as sailing around the world or mastering the ukulele.24On the other hand, if we live for many years, the value we have to other people, such as friends and family members, tends to increase.

Life differs from most commodities in the value it has for the person possessing it. If an individual has some oil but doesn’t like it, he or she can sell it for a nice profit because other people or entities25do value it. An individual’s life, however, doesn’t have the same transferable value. Relatives and loved ones may treasure your life, but ultimately it isn’t worth much if you don’t yourself, which is where quality comes in.

At the beginning of Interview with the Vampire, Lestat is a confident and happy undead monster in late 19th-century New Orleans. He creates a vampire family of sorts by siring an aristocrat named Louis and then a young girl named Claudia.26They live together happily for a while, but eventually his proteges turn on him and flee.27Near the end of the book, in modern times, Lestat is living in squalor28, barely alive. Despite his immortality and the automatic fulfillment of his biological baseline—as long as he drinks blood—he’s miserable after years of being alone with the memory of his family’s rejection.29The message is clear: It’s not enough to simply exist.

Most vampire fiction falls firmly within the realm30of horror, but Rice’s books read more like psychological case studies; the vampire characters comment on the human effects of technology and progress. With technology extending our lives and improving our health, the analogy fits better today than ever before: Humans may not be vicious psychopaths who drink the blood of innocents, but we are becoming more akin to vampires in that way.31Age affects Rice’s characters in different ways: Some become wise and contented while others grow vain and egotistical32. Which path are we treading as we inch toward immortality?33

1. caveman: 穴居人,史前时代居住在洞穴里的人;Lestat: 吸血鬼莱斯塔特,美国作家安妮·赖斯的奇幻小说《夜访吸血鬼》(Interview with the Vampire)中的主角之一;vampire: 吸血鬼;kin: [总称]家人,亲属。

2. transform into: 转变成;bat: 蝙蝠;mist: 薄雾;a host of: 许多,大量。

3. primitive: 原始的,远古的。

4. 原始穴居人如果格外幸运的话,也许会活到四十来岁,但他们更有可能会在20岁之前就因肺炎、饥饿或者受伤而死亡——而且前提是不能在幼儿期夭折。exceptionally: 不寻常地,极其;succumb to: 患重病,死于……;pneumonia: 肺炎;infancy: 婴儿期,幼年。

5. life expectancy: 平均(预期)寿命。

6. count oneself fortunate to: 因做……而认为自己很幸运。

7. lifespan: 寿命;pick up: 好转,改善;proliferate: 激增;infant mortality: 婴儿死亡率。

8. eternity: 永世,永恒。

9. empirically: 经验主义地,单凭经验地。

10. 1900年美国三大死亡率最高的疾病——肺炎或流感、肺结核、肠胃感染——没有出现在2010年的健康杀手名单中,而是与天花、坏血病和风疹这些历史上曾经的疑难杂症一样,被归到易治疾病行列中去了。influenza: 流感;tuberculosis: 肺结核; gastrointestinal: 肠胃的; banish to: 把……放逐到……,文中指归为;manageability: 易处理,易办;smallpox: 天花;scurvy: 坏血病;rubella: 风疹。

11. airways disease: 呼吸道疾病。

12. predecessor: 前任,(被取代的)原有事物;self-inflicted: 自己造成的。

13. eminently: 非常,极其。

14. gadget: 小工具;comprehensively: 全面地,综合地。

15. monitoring: 监控;wristband: 腕带;Nike Fuelband: 耐克智能健身腕带;Fitbit: 指美国Fitbit公司推出的健身腕带,能帮助用户记录自己的运动和健康数据;hit: n. 轰动,成功而风靡一时的事物。

16. Sensoria’s Fitness Sock: 一款智能袜子,能记录用户的跑步速度、路程和步伐;gauge: 测量;footfall: 脚步;gait: 步态,步法。

17. HapiFork: 一款智能餐叉,能够提醒人们减慢进食速度,养成更健康的饮食习惯;buzz: 发出嗡嗡声。

18. Anne Rice: 安妮·赖斯,美国当代著名的小说家,有“吸血鬼之母”之称,主要作品有12部,总称为《吸血鬼编年史》,《夜访吸血鬼》是其一。

19. catastrophe: 大灾难。

20. perspective: 观点。

21. mourn: 哀悼;grief-stricken: 极度悲伤的。

22. conversely: 相反地。

23. finite resource: 有限资源;fetch: 卖得……价格。

24. indulge in: 沉湎于;extraneous: 无关的,不必要的;ukulele: 尤克里里琴(夏威夷的四弦琴)。

25. entity: 实体,存在。

26. sire: 原意指“成为……的父亲”,此处指吸血鬼用自己的血创造出另一个吸血鬼;aristocrat: 贵族。

27. protege: 被保护者,门徒;turn on: 突然袭击。

28. squalor: 肮脏,邋遢。

29. 尽管莱斯塔特可以长生不老,并且只要吸血就能随时自动延长寿命,但多少年来他独自生活,只能与被家人抛弃的记忆为伴,终究还是悲惨的。immortality: 不朽,永生;baseline:(尤指医学或科学中的)基线,准线 。

30. realm: 领域。

31. analogy: 相似,类似;vicious: 恶毒的;psychopath: 精神病患者;akin to: 类似于。

32. egotistical: 自我为中心的。

33. tread: 踩,踏,此处指走向;inch: v. 缓慢移动。