恐惧情绪面孔和身体姿势加工的比较:事件相关电位研究*

2015-02-10张丹丹柳昀哲陈玉明

张丹丹 赵 婷 柳昀哲 陈玉明

(深圳大学情绪与社会认知科学研究所, 深圳 518060)

1 引言

在社会交往过程中, 情绪性信息可通过多种载体传递, 包括面孔、身体姿势、语音、文字、音乐等(Altarriba, 2012; Garrido-Vásquez, Jessen, & Kotz,2011)。其中, 面孔和身体姿势是日常交流互动中最重要的视觉性情绪载体。

对情绪性面孔的研究, 最早可追溯至达尔文的六种情绪类型, 时至今日, 科学家在面孔及面孔表情加工领域已积累了相当丰富的知识(Eimer &Holmes, 2007; Lindquist, Wager, Kober, Bliss-Moreau,& Barrett, 2012; Sabatinelli et al., 2011; Vuilleumier& Pourtois, 2007)。面孔加工的特异性脑区主要包括梭状回面孔区(fusiform face area, FFA) (Kanwisher,McDermott, & Chun, 1997)以及枕叶面孔区(occipital face area, OFA) (Gauthier et al., 2000)。事件相关电位(event-related potential, ERP)研究发现, N170是面孔加工的特异性成分, 其源定位结果位于 FFA(Schendan & Ganis, 2013)。加工情绪性面孔时, ERP的早期成分(如P1)早在刺激呈现后100 ms左右就出现对负性面孔特别是恐惧面孔的波幅增强, 有研究者认为这体现了P1 对负性面孔的低频空间信息(如睁大的双眼、张开的嘴)的高度敏感性(Pourtois,Dan, Grandjean, Sander, & Vuilleumier, 2005); 中期成分(如 N170、顶正成分(vertex positive potential,VPP))对面孔各个部件的细节以及整个面孔的构造进行初步加工, 但此阶段得到的信息仅可用于区分情绪性面孔和中性面孔, 即实现情绪与非情绪信息的分离(Eimer & Holmes, 2007; Jiang et al., 2009;Pourtois et al., 2005); 晚期成分(如P3)可进一步评估与面孔情绪效价有关的更细致的信息, 对不同情绪类型的面孔进行加工(Luo, Feng, He, Wang, &Luo, 2010; Zhang, Luo, & Luo, 2013a, 2013b)。

相比于情绪性面孔, 人们对情绪性身体姿势的研究起步较晚, 该领域还有大量科学问题尚待解决(de Gelder, Snyder, Greve, Gerar, & Hadjikhani,2004)。目前已知, 加工身体姿势的特异性脑区主要包括梭状回身体区(fusiform body area, FBA) (Peelen& Downing, 2005)以及外纹状皮层身体区(extrastriate body area, EBA) (Downing, Jiang, Shuman, &Kanwisher, 2001)。与情绪性面孔加工类似(Lindquist et al., 2012), 个体在加工不同情绪种类的身体姿势时, 激活的脑区不尽相同。例如, 虽然恐惧和愤怒的身体姿势均可激活杏仁核、颞叶皮层、前额叶皮层,但恐惧身体姿势还可激活右侧颞顶联合区, 而愤怒身体姿势还可激活前运动皮层(Pichon, de Gelder,& Grezes, 2009)。另外, 情绪性身体姿势也可在皮层诱发早(P1)、中(N170/VPP)、晚期(P3)的ERP成分(Gu, Mai, & Luo, 2013; Meeren, van Heijinsbergen,& de Gelder, 2005; Stekelenburg & de Gelder, 2004)。

加工身体姿势和加工面孔的脑区相邻(EBA与OFA相邻, FBA与FFA有部分重叠) (Schwarzlose,Baker, & Kanwisher, 2005), 且情绪性身体姿势和面孔可诱发相似的ERP成分。更重要的是, 面孔表情和身体姿势表情的加工在很大程度上存在相互影响(Aviezer et al., 2008; Aviezer, Trope, & Todorov,2012; Kret, Stekelenburg, Roelofs, & de Gelder, 2013;Meeren et al., 2005; Mondloch, Nelson, & Horner,2013; van den Stock, Righart, & de Gelder, 2007)。基于上述三点原因, 我们认为在研究中对比考察大脑对情绪性身体姿势和情绪性面孔的加工非常有必要(Peelen & Downing, 2007)。

表情加工研究的热点之一在于个体对负性情绪的关注, 即“负性偏向(negativity bias)” (Cacioppo& Gardner, 1999)。功能磁共振成像研究发现, 与中性身体姿势相比, 恐惧身体姿势在 EBA产生了更大激活(van den Stock, Vandenbulcke, Sinke, & de Gelder, 2012)。ERP研究发现, 无论是面孔还是身体姿势, 恐惧表情均比中性表情在早期阶段得到了更多的加工, 表现为早期的 P1成分在恐惧条件下的波幅更大(Luo et al., 2010; Gu et al., 2013)。在恐惧身体姿势及面孔加工的中期阶段, Stekelenburg和de Gelder (2004)发现, 与身体姿势相比, 面孔诱发的N170幅度增大, 潜伏期延长, 而VPP在身体姿势与面孔两个条件间无显著差异(但有类似于N170的趋势)。另外, VPP可区分中性与恐惧的身体姿势, 而N170能区分中性与恐惧的面孔。

目前在恐惧情绪面孔和身体姿势的加工方面还存在以下问题:1) 在早期阶段(P1阶段), 情绪载体是否会影响恐惧情绪的加工?即恐惧性身体姿势和面孔的 P1幅度是否存在差别?在一项以愤怒和恐惧的身体姿势及面孔为实验材料的研究中(Meeren et al., 2005), 作者发现与身体姿势相比,面孔诱发的 P1幅度增大, 潜伏期延长。但当前缺乏以中性表情为基线的、对恐惧性身体姿势和面孔P1成分的比较研究。2) 在加工的中期阶段, 情绪载体对N170和VPP的影响还有待进一步澄清。目前已发现面孔诱发的N170比身体姿势诱发的N170具有更大的幅度和更长的潜伏期(情绪载体效应)(Meeren et al., 2005; Stekelenburg & de Gelder,2004), 但VPP仅表现出类似于N170的情绪载体差异的趋势(Stekelenburg & de Gelder, 2004)。另外,该N170结果与另一项非情绪性的研究相反(后者发现身体姿势诱发的 N170潜伏期更长) (Thierry,Pegna, Dodds, Roberts, Basan, & Downing, 2006)。此外, Stekelenburg和de Gelder (2004)发现VPP不能区分中性与恐惧的面孔, 这与情绪面孔研究的主流观点不符(Campanella, Quinet, Bruyer, Crommelinck,& Guerit, 2002; Eimer & Holmes, 2007; Luo et al.,2010; Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b)。我们推测该VPP的两项结果是由于Stekelenburg和de Gelder (2004)研究的被试量太少造成的假阴性(仅 12名)。3) 在相关研究中未发现对晚期阶段(P3成分)的考察。

本文在Stekelenburg和de Gelder (2004)研究的基础上, 扩大被试量, 以中性表情为基线, 对比考察恐惧/中性的面孔和身体姿势诱发的早(P1)、中(N170和VPP)、晚(P3)三个时期的ERP成分。根据已有文献提供的证据, 本文作者对实验结果提出以下预期:1) 在身体姿势和面孔加工的早期阶段, P1成分不但存在“负性偏向”, 还会表现出情绪载体效应; 2) 中期阶段的N170和VPP可能具有相似的表现, 即面孔条件下的幅度更大、潜伏期更长, 且在恐惧和中性条件间表现出幅度差异 3) 晚期阶段的P3成分体现了大脑对情绪性刺激的深入加工(Luo et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b), 因此很可能同时受到情绪效应(恐惧与中性相比)和情绪载体效应的影响。与Stekelenburg和de Gelder (2004)的研究相比, 本研究可获得情绪性面孔和身体姿势加工的更可靠的神经电生理证据, 从而加深我们对情绪性身体姿势加工脑机制的了解, 为情绪认知障碍的诊断提供更多的生物标记物。

2 方法

2.1 被试

共40名(男女各20名)年龄分布在19~24岁的健康成年被试参加了实验。被试均为右利手, 视力或矫正视力正常。实验前均被告知了实验目的, 并签署了知情同意书。本实验已经深圳大学伦理委员会批准。

2.2 实验材料及程序

身体姿势图片40张, 男女演员各半, 选自中国身体姿势表情图片库(Gu et al., 2013), 该库的建立参考了西方国家的身体姿势表情图片库(de Gelder& van den Stock, 2011)。面孔图片40张, 男女演员各半, 选自中国面孔表情图片库(龚栩, 黄宇霞, 王妍, 罗跃嘉, 2011)。以上材料包含数量均等的恐惧和中性图片(各20张)。所有的材料以相同的对比度和亮度呈现在灰色背景上(中央呈现, 3.0° × 3.5°)。

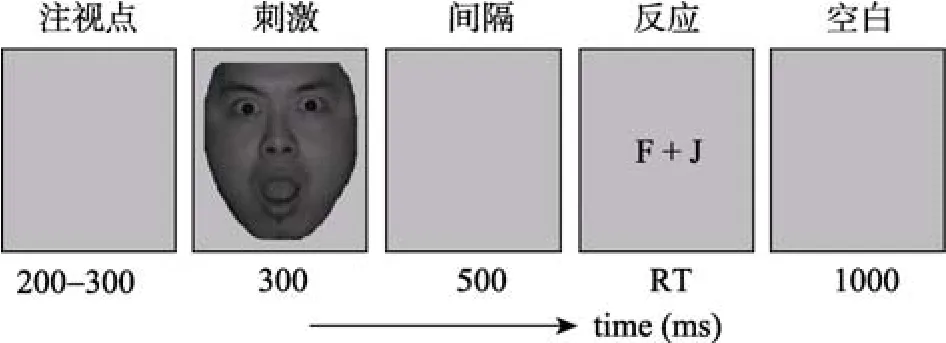

实验程序如图1所示。面孔或身体姿势图片呈现300 ms。被试的任务是又快又准地判断图片的情绪类型, 恐惧和中性分别对应F键和J键(左右手食指按键, F键和J键对应的情绪类型在被试间平衡)。实验依据情绪载体(面孔或身体姿势)分两个 block进行, block的顺序在被试间平衡。每个block内恐惧和中性图片随机出现。每张图片重复呈现 3次,即每个条件60个试次。实验共60 × 2 (情绪类型) ×2 (情绪载体) = 240个试次。

图1 实验程序示意图

2.3 数据采集及分析

使用64导脑电放大器(Brain Products, Gilching,德国)采集脑电和眼电数据, 电极的阻抗低于5 kΩ。参考电极置于左侧乳突, 离线转为双侧乳突平均参考。脑电中的水平和垂直眼电利用Neuroscan软件(Scan 4.3)内置的回归程序去除。

数据分析采用 Matlab R2011a (MathWorks,Natick, 美国)。脑电数据依次经过以下处理:滤波(0.01~30 Hz, 零相位延迟)、分段(–200 至 800 ms)、基线矫正(–200至0 ms)、叠加平均(仅选用行为反应正确的试次进行叠加)。

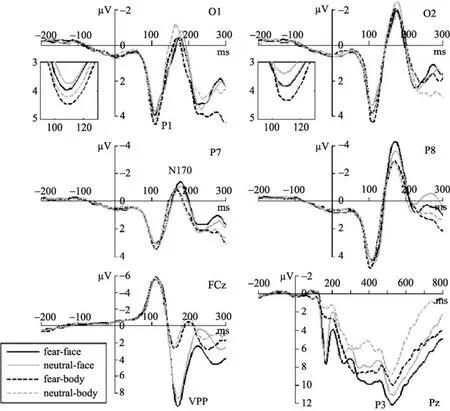

本文分析的 ERP成分包括枕区的 P1, 颞枕区的N170, 中央–额区的VPP, 以及顶区的P3。由于早期和中期的 ERP成分具有较尖锐的峰值, 故对P1、N170、VPP采用基线–峰值进行度量; 而晚期的成分波形较钝, 故对P3采用平均波幅进行度量。为了获得可靠的高信噪比的 ERP结果, 每个 ERP成分由该成分波幅最大的2~3个电极点的平均值计算而得。根据脑电地形图、ERP波形图、以及已有的相关文献选取电极点的位置和 ERP成分的分析时间窗(Liu, Zhang, & Luo, 2014; Luck, 2005; Zhang,Liu, Wang, Chen, & Luo, 2014)。具体而言, P1成分的分析电极点为O1, O2, PO3, PO4 (数据分别取左右半球的均值), 峰值检测窗口为90~130 ms。N170成分的分析电极点为P7, P8, PO7, PO8(数据分别取左右半球的均值), 峰值检测窗口为 150~200 ms。VPP成分的分析电极点为FCz, FC1, FC2(数据取均值), 峰值检测窗口为150~200 ms。P3成分的分析电极点为Pz, P1, P2(数据取均值), 平均幅度计算窗口为450~600 ms。

2.4 统计

统计分析采用SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM, Somers,美国)。描述性统计量表示为均值±标准误。行为正确率、反应时以及VPP和P3的潜伏期/幅度采用双因素重复测量方差分析, 被试内因素为情绪类型(恐惧、中性)和情绪载体(身体姿势、面孔)。P1和N170的潜伏期及幅度采用三因素重复测量方差分析, 被试内因素为情绪类型、情绪载体、大脑半球(左半球、右半球)。

3 结果

3.1 行为

3.1.1 正确率

3.1.2 反应时

3.2 ERP

3.2.1 P1成分

图2 实验的ERP结果

3.2.2 N170成分

3.2.3 VPP成分

3.2.4 P3成分

4 讨论

本文研究了大脑对面孔和身体姿势在恐惧和中性两种条件下的加工。行为结果发现, 与中性条件相比, 恐惧条件下的正确率更高, 反应时更短。该结果表明, 与情绪性面孔相似, 情绪性身体姿势的加工也符合“负性偏向”理论。另外, 结果显示身体姿势图片对应的正确率高于面孔图片对应的正确率, 这可能是因为恐惧与中性的身体姿势在形态上的差异较大(中性条件下双臂更多地贴于躯干两旁, 恐惧的身体姿势双臂往往与躯干分离, 参见身体姿势表情图片库(de Gelder & van den Stock, 2011)),因此更容易准确区分。

本研究发现, ERP早期成分P1幅度在情绪类型和情绪载体两个因素上都存在显著的主效应。首先,恐惧比中性条件诱发更大的 P1, 符合“负性偏向”理论。其次, 身体姿势比面孔诱发更大的P1, 此结果与 Meeren等(2005)的研究不符(后者认为面孔诱发的 P1幅度更大)。两个研究在P1结果上的差异可能源于二者的情绪类别不同:本研究要求被试区分恐惧与中性情绪, 而Meeren等(2005)的研究要求被试区分恐惧与愤怒情绪。已知恐惧与中性的身体姿势在整体轮廓(即图片的低频信息)方面差异较大,而恐惧与愤怒的面孔在轮廓方面差异较小(参见身体姿势表情图片库(de Gelder & van den Stock,2011))。而我们在引言中已提到, ERP的早期成分(如P1)对图片的低频空间信息敏感, 而大脑对图片的高频信息(即细节)的加工可能发生在中期及晚期ERP成分的时间窗(Pourtois et al., 2005)。因此在本研究中, 身体姿势比面孔条件诱发更大的 P1很可能是该成分对恐惧与中性身体姿势更大的低频信息差异(与恐惧与中性面孔的低频信息差异相比)进行加工的表现。

我们发现, ERP中期成分N170和VPP在实验中具有相同的趋势:1) 能区分恐惧和中性的面孔(恐惧面孔的幅度更大), 但不能区分恐惧和中性的身体姿势; 2) 情绪载体的主效应显著, 与面孔图片相比, 身体图片诱发的 ERP幅度更小, 潜伏期更短。不少学者认为N170和VPP是由位于梭状回的同一个偶极子产生的一对共轭的ERP成分(Itier &Taylor, 2002; Jemel et al., 2003; Rossion, Joyce,Cottrell, & Tarr, 2003; Williams, Palmer, Liddell,Song, & Gordon, 2006), 另外 Stekelenburg等(Stekelenburg & de Gelder, 2004)也指出, 面孔和身体姿势诱发的 N170/VPP的头皮分布相似。N170和 VPP在本实验中表现出的相似结果, 支持这一观点。其实de Gelder小组的两项研究(Meeren et al.,2005; Stekelenburg & de Gelder, 2004)也与本文有类似结果, 只是可能由于他们的被试量太少, 造成了部分结果的假阳性或假阴性。本文的结果提示,由于大脑在情绪性身体姿势加工初期(即P1的时间窗内)已快速完成了对恐惧和中性身体姿势的初步辨识, 因此在此后的N170和VPP时期, 大脑给身体姿势图片的加工分配了较面孔加工更少的认知资源, 表现为身体姿势图片对应的 N170/VPP幅度较小, 潜伏期较短。

在情绪性面孔和身体姿势加工的晚期, ERP的P3成分在情绪类型和情绪载体两个因素上均表现出了主效应, 说明 P3可区分身体与面孔以及恐惧表情和中性表情, P3幅度在两个主效应上出现了较大的效应量, 体现了大脑在 P3阶段对情绪性信息的更深入的加工。先前对面孔表情的研究已指出,大脑在情绪加工的晚期阶段可进一步评估与效价有关的更细致的信息, P3成分能将不同情绪种类的图片区分开(Campanella et al., 2002; Krolak-Salmon,Fischer, Vighetto, & Mauguière, 2001; Williams et al.,2006)。遗憾的是本研究仅选用了恐惧和中性的情绪材料, 无法明确 P3在身体姿势加工中是否能区分开不同种类的情绪信息。

综上所述, 本文在de Gelder等人的基础上, 以较大的被试样本进一步考察了大脑对恐惧和中性身体姿势及面孔的加工时程, 回答了引言中提出的三个问题。我们的研究结果说明, 与情绪性面孔加工类似, 大脑对情绪性身体姿势的加工也是快速的,早在 P1阶段即可将恐惧和中性的身体姿势区分开来, 并且身体姿势图片诱发的 P1幅度大于面孔图片; 在加工的中期阶段, 与情绪性面孔相比, 情绪性身体姿势诱发出的N170和VPP幅度较小, 潜伏期较短, 说明此阶段大脑在身体姿势加工方面的优势不如在面孔加工方面的优势大; 在加工的晚期阶段, P3可区分情绪载体和情绪类别。本文对情绪性面孔和身体姿势的结合研究将有助于深入了解情绪脑的工作机制, 同时找到更多的情绪相关的生物标记物以帮助临床诊断具有情绪认知障碍的精神病患者的脑功能缺损。例如, 已发现自闭症患者和精神分裂症患者在面孔情绪和身体姿势情绪加工方面均存在缺陷(Grèzes, Wicker, Berthoz, & de Gelder, 2014; Hadjikhani et al., 2009; Hubert et al.,2007; Kohler, Bilker, Hagendoorn, Gur, & Gur, 2000;van den Stock, de Jong, Hodiamont, & de Gelder,2011)。下一步还可从以下几个方面对情绪性身体姿势的加工进行研究:1) 选用多种情绪类别的身体姿势材料; 2) 考察情绪性身体姿势加工的跨文化差异; 3) 对比男性和女性被试在加工男性及女性演员表演的身体姿势图片时的行为及神经表现的差异。

Altarriba, J. (2012). Emotion and mood: Over 120 years of contemplation and exploration in the American Journal of Psychology. American Journal of Psychology, 125(4),409–422.

Aviezer, H., Hassin, R. R., Ryan, J., Grady, C., Susskind, J.,Anderson, A., … Bentin, S. (2008). Angry, disgusted, or afraid? Studies on the malleability of emotion perception.Psychological Science, 19(7), 724–732.

Aviezer, H., Trope, Y., & Todorov, A. (2012). Body cues, not facial expressions, discriminate between intense positive and negative emotions. Science, 338(6111), 1225–1229.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Gardner, W. L. (1999). Emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 191–214.

Campanella, S., Quinet, P., Bruyer, R., Crommelinck, M., &Guerit, J. M. (2002). Categorical perception of happiness and fear facial expressions: An ERP study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14(2), 210–227.

de Gelder, B., Snyder, J., Greve, D., Gerard, G., & Hadjikhani,N. (2004). Fear fosters flight: A mechanism for fear contagion when perceiving emotion expressed by a whole body. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(47), 16701–16706.

de Gelder, B., & van den Stock, J. (2011). The bodily expressive action stimulus test (BEAST). Construction and validation of a stimulus basis for measuring perception of whole body expression of emotions. Frontiers in Psychology,2, 181. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00181

Downing, P. E., Jiang, Y., Shuman, M., & Kanwisher, N.(2001). A cortical area selective for visual processing of the human body. Science, 293(5539), 2470–2473.

Eimer, M., & Holmes, A. (2007). Event-related brain potential correlates of emotional face processing. Neuropsychologia,45(1), 15–31.

Garrido-Vásquez, P., Jessen, S., & Kotz, S. A. (2011).Perception of emotion in psychiatric disorders: On the possible role of task, dynamics, and multimodality. Social Neuroscience, 6(5-6), 515–536.

Gauthier, I., Tarr, M. J., Moylan, J., Skudlarski, P., Gore, J. C.,& Anderson, A. W. (2000). The fusiform "face area" is part of a network that processes faces at the individual level.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12(3), 495–504.

Grèzes, J., Wicker, B., Berthoz, S., & de Gelder, B. (2014). A failure to grasp the affective meaning of actions in autism spectrum disorder subjects. Neuropsychologia, 47(8-9),1816–1825.

Gong, X., Huang, Y. X., Wang, Y., & Luo, Y. J. (2011).Revision of the Chinese facial affective picture system.Chinese Mental Health Journal, 25(1), 40–46.

[龚栩, 黄宇霞, 王妍, 罗跃嘉. (2011). 中国面孔表情图片系统的修订. 中国心理卫生杂志, 25(1), 40–46.]

Gu, Y. Y., Mai, X. Q., & Luo, Y. J. (2013). Do bodily expressions compete with facial expressions? Time course of integration of emotional signals from the face and the body. PLoS One, 8(7), e66762.

Hadjikhani, N., Joseph, R. M., Manoach, D. S., Naik, P.,Snyder, J., Dominick, K., … de Gelder, B. (2009). Body expressions of emotion do not trigger fear contagion in autism spectrum disorder. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4(1), 70–78.

Hubert, B., Wicker, B., Moore, D. G., Monfardini, E.,Duverger, H., Da Fonséca, D., & Deruelle, C. (2007). Brief report: Recognition of emotional and non-emotional biological motion in individuals with autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,37(7), 1386–1392.

Itier, R. J., & Taylor, M. J. (2002). Inversion and contrast polarity reversal affect both encoding and recognition processes of unfamiliar faces: A repetition study using ERPs. NeuroImage, 15(2), 353–372.

Jiang, Y., Shannon, R. W., Vizueta, N., Bernat, E. M., Patrick,C. J., & He, S. (2009). Dynamics of processing invisible faces in the brain: Automatic neural encoding of facial expression information. NeuroImage, 44(3), 1171–1177.

Jemel, B., Schuller, A. M., Cheref-Khan, Y., Goffaux, V.,Crommelinck, M., & Bruyer, R. (2003). Stepwise emergence of the face-sensitive N170 event-related potential component. Neuroreport, 14(16), 2035–2039.

Kanwisher, N., McDermott, J., & Chun, M. M. (1997). The fusiform face area: A module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. The Journal of Neuroscience,17(11), 4302–4311.

Kohler, C. G., Bilker, W., Hagendoorn, M., Gur, R. E., & Gur,R. C. (2000). Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia:Association with symptomatology and cognition. Biological Psychiatry, 48(2), 127–136.

Kret, M. E., Stekelenburg, J. J., Roelofs, K., & de Gelder, B.(2013). Perception of face and body expressions using electromyography, pupillometry and gaze measures. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 28. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00028

Krolak-Salmon, P., Fischer, C., Vighetto, A., & Mauguière, F.(2001). Processing of facial emotional expression: Spatiotemporal data as assessed by scalp event-related potentials.European Journal of Neuroscience, 13(5), 987–994.

Lindquist, K. A., Wager, T. D., Kober, H., Bliss-Moreau, E., &Barrett, L. F. (2012). The brain basis of emotion: A metaanalytic review. Behavioral Brain Science, 35(3), 121–143.

Liu, Y. Z., Zhang, D. D., & Luo, Y. J. (2014). How disgust facilitates avoidance: An ERP study on attention modulation by threats. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10,598–604.

Luck, S. J. (2005). An introduction to the Event-related potential technique. London: The MIT Press.

Luo, W. B., Feng, W. F., He, W. Q., Wang, N. Y., & Luo, Y. J.(2010). Three stages of facial expression processing: ERP study with rapid serial visual presentation. NeuroImage,49(2), 1857–1867.

Meeren, H. K., van Heijnsbergen, C. C., & de Gelder, B.(2005). Rapid perceptual integration of facial expression and emotional body language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,102(45), 16518–16523.

Mondloch, C. J., Nelson, N. L., & Horner, M. (2013).Asymmetries of influence: Differential effects of body postures on perceptions of emotional facial expressions.PLoS One, 8(9), e73605.

Peelen, M. V., & Downing, P. E. (2005). Selectivity for the human body in the fusiform gyrus. Journal of Neurophysiology,93(1), 603–608.

Peelen, M. V., & Downing, P. E. (2007). The neural basis of visual body perception. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(8),636–648.

Pichon, S., de Gelder, B., & Grèzes, J. (2009). Two different faces of threat. Comparing the neural systems for recognizing fear and anger in dynamic body expressions.NeuroImage, 47(4), 1873–1883.

Pourtois, G., Dan, E. S., Grandjean, D., Sander, D., & Vuilleumier,P. (2005). Enhanced extrastriate visual response to bandpass spatial frequency filtered fearful faces: Time course and topographic evoked-potentials mapping. Human Brain Mapping, 26(1), 65–79.

Rossion, B., Joyce, C. A., Cottrell, G. W., & Tarr, M. J. (2003).Early lateralization and orientation tuning for face, word,and object processing in the visual cortex. NeuroImage,20(3), 1609–1624.

Sabatinelli, D., Fortune, E. E., Li, Q. Y., Siddiqui, A., Krafft,C., Oliver, W. T., … Jeffries, J. (2011). Emotional perception:Meta-analyses of face and natural scene processing.NeuroImage, 54(3), 2524–2533.

Schendan, H. E., & Ganis, G. (2013). Face-specificity is robust across diverse stimuli and individual people, even when interstimulus variance is zero. Psychophysiology, 50(3),287–291.

Schwarzlose, R. F., Baker, C. I., & Kanwisher, N. (2005).Separate face and body selectivity on the fusiform gyrus.The Journal of Neuroscience, 25(47), 11055–11059.

Stekelenburg, J. J., & de Gelder, B. (2004). The neural correlates of perceiving human bodies: An ERP study on the body-inversion effect. Neuroreport, 15(5), 777–780.

Thierry, G., Pegna, A. J., Dodds, C., Roberts, M., Basan, S., &Downing, P. (2006). An event-related potential component sensitive to images of the human body. NeuroImage, 32(2),871–879.

van den Stock, J., de Jong, S. J., Hodiamont, P. P. G., & de Gelder, B. (2011). Perceiving emotions from bodily expressions and multisensory integration of emotion cues in schizophrenia. Social Neuroscience, 6(5–6), 537–547.

van den Stock, J., Righart R., & de Gelder B. (2007). Body expressions influence recognition of emotions in the face and voice. Emotion, 7(3), 487–494.

van den Stock, J., Vandenbulcke, M., Sinke, C. B. A., & de Gelder, B. (2012). Affective scenes influence fear perception of individual body expressions. Human Brain Mapping,35(2), 492–502.

Vuilleumier, P., & Pourtois, G. (2007). Distributed and interactive brain mechanisms during emotion face perception: Evidence from functional neuroimaging. Neuropsychologia, 45(1),174–194.

Williams, L. M., Palmer, D., Liddell, B. J., Song, L., &Gordon, E. (2006). The ‘when’and ‘where’of perceiving signals of threat versus non-threat. NeuroImage, 31(1),458–467.

Zhang, D. D., Liu, Y. Z., Wang, X. C., Chen, Y. M., & Luo, Y.J. (2014). The duration of disgusted and fearful faces is judged longer and shorter than that of neutral faces:Tattention-related time distortions as revealed by behavioral and electrophysiological measurements. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 293. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00293

Zhang, D. D., Luo, W. B., & Luo, Y. J. (2013a). Single-trial ERP analysis reveals facial expression category in a three-stage scheme. Brain Research, 1512, 78–88.

Zhang, D. D., Luo, W. B., & Luo, Y. J. (2013b). Single-trial ERP evidence for the three-stage scheme of facial expression processing. Science China (Life Sciences), 56(9), 835–847.