错误记忆的可植入性

2015-02-01刘振亮刘田田韩佳慧沐守宽

刘振亮 刘田田 韩佳慧 沐守宽

(闽南师范大学教育科学学院, 漳州 363000)

错误记忆分为自发性错误记忆和植入性错误记忆(Brainerd & Reyna, 2005)。自发性错误记忆是指凭借个体内部加工过程而导致的错误记忆, 而植入性错误记忆是指通过某种方法使人们形成的错误记忆。二者的区别在于, 前者是内部加工, 后者是外部加工。本文的重点在于植入性错误记忆。在某些情况下, 植入性错误记忆还伴随着一些感觉、情感以及细节特征, 使得杜撰事件变得更加真实(Loftus & Bernstein, 2005)。植入性错误记忆的研究起源于回忆真实性对司法公正的影响。人类记忆存在的大量错误会严重影响司法系统的公正性(Belli, 2012; Clancy, 2009a; Davis & Loftus,2007)。例如, Loftus (1975)的碎玻璃实验曾对回忆的真实性进行了检验。

近年来, 错误记忆的研究逐渐从可植入性过渡到对个体的思想、态度和行为的影响及其植入机制。本文首先阐述植入错误记忆的可能性、植入范式以及植入标准等基本问题; 然后讨论植入性错误记忆的影响、与真实记忆的辨别、心理机制以及存在的问题等; 最后, 提出该研究未来可能的发展方向。

1 错误记忆的可植入性

1.1 植入的可能性

错误记忆的研究证实了记忆的不稳定性、重构性以及可塑性(Davis & Loftus, 2007; Loftus,2005)。错误信息可以通过某种方法植入到记忆系统中。研究表明, 可以诱导人们相信小时候在一个商场里迷路(Loftus & Pickrell, 1995), 或在婚礼上把酒洒在了新郎的父母身上(Hyman, Husband,& Billings, 1995)。但在植入过程中, 被诱导事件是否真实发生过不得而知。换句话说, 是诱发真实记忆, 还是植入错误记忆?为解决这个问题,研究者植入了不可能或没有发生的事件(Clancy,2009b)。研究表明, 实验操作使被试相信小时候经历了恶魔附体(Mazzoni, Loftus, & Kirsch, 2001)或在手术中从他们的手指上切取一块皮肤, 而事实上, 这件事情根本没有发生过(Mazzoni & Memon,2003)。总之, 错误记忆具有可植入性。不过, 可植入性会受到诸多因素影响, 如引导问题或其他人的报告(Foster, Huthwaite, Yesberg, Garry, &Loftus, 2012; Loftus & Palmer, 1974)、与他人的交流(Gabbert, Memon, Allan, & Wright, 2004; Peterson,Kaasa, & Loftus, 2009; Wright, Self, & Justice,2000)、自我或其他人的期望(Foster & Garry, 2012;Schacter, 2002)、有意的暗示(Davis & Loftus, 2007;Takarangi, Parker, & Garry, 2006)、问题的措辞(Loftus,1975)、态度的一致性(Frenda, Knowles, Saletan, &Loftus, 2013)以及事件记忆的性质等(Morgan,Southwick, Steffian, Hazlett, & Loftus, 2013)。

1.2 植入范式

植入错误记忆的最初范式是 Loftus (1997)使用的商场迷失技术(Lost in the Mall Technique),在此基础上逐渐发展出错误反馈技术、想象膨胀范式、照片修改范式以及盛情—欺骗范式, 这些范式的主要程序是暗示被试在小时候或过去经历过某个并未真实发生的关键事件, 由于时间问题,被试遗忘了关键事件。研究者通过错误反馈和诱导性提问等方式让被试不断想象关键事件, 使被试逐渐相信其确实发生过。

1.2.1 错误反馈技术

错误反馈技术(False-Feedback Technique)主要是指研究者收集被试的基本信息, 然后对这些信息重新编排, 进而植入错误的关键信息(虚假信息) (Spanos, Burgess, Burgess, Samuels, & Blois,1999)。在研究中, 首先通过问卷、量表或访谈等方式收集植入错误记忆的相关信息。然后, 声称这些信息将输入计算机, 分析他们童年或过去经历(许多经历已经被遗忘), 并输出相应的信息清单(信息清单是为实验需要而编制)。为使反馈更加真实, 在信息清单中, 除需要植入的关键信息外,还包括许多真实信息。最后, 让被试花一定的时间熟悉信息清单的内容。错误反馈技术采用前后测实验设计, 被试需要完成两次同样的问题清单(反馈后, 间隔一定时间), 前后两次的差异作为植入效果。研究发现, 错误反馈技术能有效降低被试对特定食物的偏好以及产生相应的行为回避倾向(Bernstein, Laney, Morris, & Loftus, 2005a)。此外, 与普遍性反馈技术(他人经历的关键事件)相比, 个性化反馈技术(被试经历的关键事件)能够引起更多的错误记忆以及更加具体的行为结果(Scoboria, Mazzoni, Jarry, & Bernstein, 2012)。

1.2.2 想象膨胀范式

想象膨胀(Imagination Inflation)范式是由想象引发的信心膨胀。经典的想象膨胀范式主要包括三个步骤:第一, 要求被试完成一份包括多项童年生活事件的清单, 被试需要判定事件发生的可能性(采用等级评分)。第二, 间隔一段时间之后(至少两周), 重新召集被试, 要求其想象清单列举的事件。第三, 要求被试再次填写生活事件清单, 并同时判定事件发生的可能性, 但所填事件清单可以与第一次不同。想象膨胀范式主要评估被试在想象前后可能性评分的变化, 从而分析植入错误记忆的效果。Garry, Manning, Loftus和Sherman等(1996)发现, 与未想象过事件相比, 想象过事件的可能性评分显著提高。

1.2.3 照片修改范式

照片被视为童年或过去经历的权威证据。因为, 照片提供的信息很容易被判断为真实经历或事件(Wade, Garry, Read, & Lindsay, 2002)。在照片修改范式(Doctored Photographs Paradigm)中, 选用被试遗忘的童年或过去经历的照片作为实验材料, 照片分为真实照片(未修改)和虚假照片(修改后)。虚假照片是植入错误记忆的关键事件。此范式包括三个阶段(每阶段间隔 3-7天)。第一阶段,要求被试对呈现的每张照片尽可能多地回忆有关照片描绘的情节。当被试不能有效回忆时, 通过补充时间、情境恢复以及引导想象帮助被试回忆事件。访谈后要求被试每晚花一定时间想象有关照片遗忘的细节。第二阶段, 仅询问被试是否记得更多关于遗忘事件的细节, 接着重复情境恢复以及引导想象技术, 此阶段无需记录和评定可能性。第三阶段与第一阶段相似, 不同之处在于, 访谈人员告诉被试实验材料中有一张照片是虚构的,令其指出或猜测哪一个是关键事件。Wade等(2002)采用此范式发现, 通过修改照片能使被试回忆出更多有关关键事件的细节, 并提高事件发生的确信程度。此外, Sacchi, Agnoli和 Loftus(2007)发现, 通过修改历史事件的照片, 可以改变人们对过去事件的记忆、态度甚至行为倾向。

1.2.4 盛情—欺骗范式

近年来, Zhu, Chen, Loftus, Lin和Dong (2010)提出一种新的范式:盛情—欺骗范式(Treat-and-Trick Paradigm)。该范式分为两个阶段, 前一阶段是盛情阶段, 后一阶段是欺骗阶段。在盛情阶段,首先给被试以幻灯片的方式呈现故事, 对事件进行真实解释和说明; 然后对呈现的故事进行测验。在欺骗阶段, 重复上述过程, 但故事换为新故事, 且作误导解释与说明。研究发现, 与标准的三段植入范式(初始事件、信息植入和测验)相比, 盛情—欺骗范式引发更多的错误记忆。

1.3 植入标准

既然错误记忆具有可植入性, 那么, 如何界定是否成功地植入了错误记忆?如果以事件的可能性评分作为标准, 则显得武断, 因为无法推测有多少人是由于植入技术而提高了对关键事件的确信程度。因此, 实验者会采用相对保守且理性的标准, 即被试起初并不相信关键事件的发生或发生的可能性较低, 在植入技术的操作之后, 被试对关键事件的确信程度有所增加, 并报告关键事件以及相信关键事件发生(Morris, Laney, Bernstein,& Loftus, 2006)。此外, 成功植入的标准又可以进一步划分为植入错误记忆(相信关键事件发生, 并能详述细节)和植入错误信念(相信关键事件发生,但不能叙述详情) (Scoboria, Mazzoni, Kirsch, &Relyea, 2004)。

2 植入性错误记忆的影响

如前所述, 错误记忆具有可植入性, 不同植入范式均可引发错误记忆。那么, 植入性错误记忆会产生哪些影响呢?研究发现, 通过植入范式可以产生一些不可思议的错误记忆(Geraerts et al.,2007; Loftus & Davis, 2006), 如宗教仪式性侵害(Scott, 2001)、前世(Peters, Horselenberg, Jelicic, &Merckelbach, 2007)以及被外星人绑架(Clancy,2009b)等。虽然这类错误记忆是不真实的, 但仍能引起人们痛苦的情绪体验(McNally et al., 2004)。

Bernstein等(2005a)以及 Bernstein, Laney,Morris和Loftus (2005b)首次对植入性错误记忆的影响进行了验证。他们给被试植入与食物有关的错误记忆, 使被试相信小时候因为吃某种特定食物而生病, 并通过错误反馈的方法增加被试认定事件发生的确信程度。结果发现, 被试报告对关键食物的偏好降低, 且很少愿意再吃这种食物。这些研究证实了植入性错误记忆能够影响态度。

Scoboria, Mazzoni和Jarry (2008)给被试植入小时候因为吃变质的桃子酸奶而生病的错误记忆,一周后, 被试被重新召集, 此时, 实验者给被试提供各种口味的酸奶(包括桃子酸奶)和饼干吃。结果发现, 与控制组相比, 被试很少食用桃子酸奶,但在饼干上不存在差异。Geraerts等(2008)也发现,给被试植入吃鸡蛋沙拉而生病的错误记忆后, 被试很少愿意去吃鸡蛋沙拉三明治, 而且在饮食行为上也是如此。可见, 植入性错误记忆不仅可以改变人们的态度, 也可以影响人们的行为(Geraerts et al., 2008; Scoboria et al., 2008)。

植入性错误记忆对态度和行为的影响不止仅表现在饮食方面。研究发现, 通过想象膨胀范式植入有关品牌观念或意识的错误记忆, 可以影响被试对品牌的态度以及消费行为(Berkowitz,Laney, Morris, Garry, & Loftus, 2008; Howard &Kerin, 2011; Mantonakis, Wudarzewski, Bernstein,Clifasefi, & Loftus, 2013)。此外, 通过植入错误记忆的方法还能够增加攻击意识, 诱发攻击行为(Laney & Takarangi, 2013)。不仅如此, 植入性错误记忆还能改变人们参加社会活动的意愿。研究发现, 修改过去公共事件的照片(和平示威变成暴力对抗), 可以减少被试将来参加抗议活动的意愿(Sacchi et al., 2007)。

3 植入性错误记忆与真实记忆的辨别

当错误记忆植入到经验中, 植入性错误记忆会与真实记忆产生混淆。如何有效区分植入性错误记忆与真实记忆就显得格外重要(Bernstein &Loftus, 2009a)。通常人们对真实记忆要比植入性错误记忆更加自信(Loftus & Pickrell, 1995; Wade et al., 2002)。但与真实记忆相比, 植入性错误记忆缺乏连贯性(Porter, Yuille, & Lehman, 1999)。以下尝试从影响、情绪、持续性以及生理机制四个角度对植入性错误记忆与真实记忆加以区分。

3.1 影响

在现实生活中, 真实记忆可以产生相应的行为结果, 如过去某个人侮辱了你, 你可能不会期待下次相遇。然而, 植入性错误记忆是否会产生相同的影响?大量研究表明, 植入性错误记忆与真实记忆一样, 会影响人们的思想、态度和行为(Bernstein et al., 2005a, 2005b; Berkowitz et al.,2008; Laney & Loftus, 2008; Laney, Morris, Bernstein,Wakefield, & Loftus, 2008)。所以, 从影响结果来看, 还不能对二者作出有效区分。

3.2 情绪

植入性错误记忆是否会像真实记忆一样, 产生相应的情绪感受?McNally等(2004)招募一些相信曾被外星人绑架的被试, 然后测量他们 “被绑架”记忆、情绪记忆及非情绪记忆的生理反应,发现“被绑架”者与其它经历真实生活创伤的被试一样, 均产生相应的情绪体验。Laney和 Loftus(2008)通过植入错误记忆的方法得出同样的结论,情绪测量不能有效区分植入性错误记忆与真实记忆。

3.3 持续性

研究发现, 植入性错误记忆及其结果能够持续至少数月之久(Geraerts et al., 2008); 也有研究发现, 错误记忆及其行为结果虽然可以持续很长时间, 但保持的质量会随着时间的推移而逐渐降低(Laney, Fowler, Nelson, Bernstein, & Loftus,2008; Laney & Loftus, 2008)。此外, 适度曝光误导信息引起的错误记忆持续时间可达 18个月之久,同时其记忆线索的强度与真实记忆相同(Zhu et al.,2012)。这些结果表明, 植入性错误记忆像真实记忆一样具有持续性。

3.4 生理机制

fMRI研究发现, 真实记忆与错误记忆有着相同的脑区, 包括前额叶(prefrontal)、顶叶(parietal)以及颞皮层内侧(medial temporal cortices)等(Gutchess& Schacter, 2012; Schacter & Slotnick, 2004; Straube,2012)。而且, 植入性错误记忆会像真实记忆一样导致神经重组(Schacter & Slotnick, 2004)。不过真实记忆更多地激活视觉皮层(visual cortex), 而错误记忆则更多地激活听觉皮层(auditory cortex)(Schacter & Loftus, 2013; Slotnick & Schacter,2004, 2006)。尽管二者激活的脑区不同, 但激活的脑区与真实记忆和植入性错误记忆的关系仍不明确(Stark, Okado, & Loftus, 2010)。

综上所述, 影响、情绪、持续性均不足以有效地区分植入性错误记忆和真实记忆, 从神经生理机制角度区分或许是一个不错的选择。

4 植入性错误记忆的心理机制

目前, 有关植入性错误记忆心理机制的解释主要有两种理论, 即联结观和多阶段模型。

4.1 联结观

联结观认为, 错误反馈技术可能改变了具体记忆与行为的联结。例如, 人们想象一个与草莓冰淇淋有关的不愉快的经历时, 可能产生一种记忆线索——草莓冰淇淋不好。这种联结也会使人们打消现在或将来想吃草莓冰淇淋的想法, 进而影响到与吃草莓冰淇淋有关的行为结果(Bernstein et al., 2005b)。像植入错误记忆的范式一样, 错误反馈技术通过创建一个条件刺激(不愉快)与非条件刺激(吃草莓冰淇淋)的联结使被试产生对某种食物的态度转变或回避行为。但有研究发现, 被试接受对关键食物与积极或消极词汇的联结训练之后, 植入性错误记忆并不能改变被试对关键食物的偏好(Mantonakis, Bernstein, & Loftus, 2011)。这表明, 联结观对植入性错误记忆的解释有待于进一步验证。

4.2 多阶段模型

为了解释植入性错误记忆的形成, Mazzoni等(2001)提出了三阶段模型(three-step model), 认为错误记忆的形成包括三个阶段:可信性(plausibility, 植入的关键事件在当时的情境是可能发生的)、错误信念(false belief, 植入的关键事件曾经发生)和错误记忆(false memory, 形成植入关键事件的错误记忆)。Scoboria等(2004)完善了此模型, 对可信性进行补充, 加入了个人可信性,即植入的关键事件除在当时情境可能发生外, 对被植入者也是可能发生的。

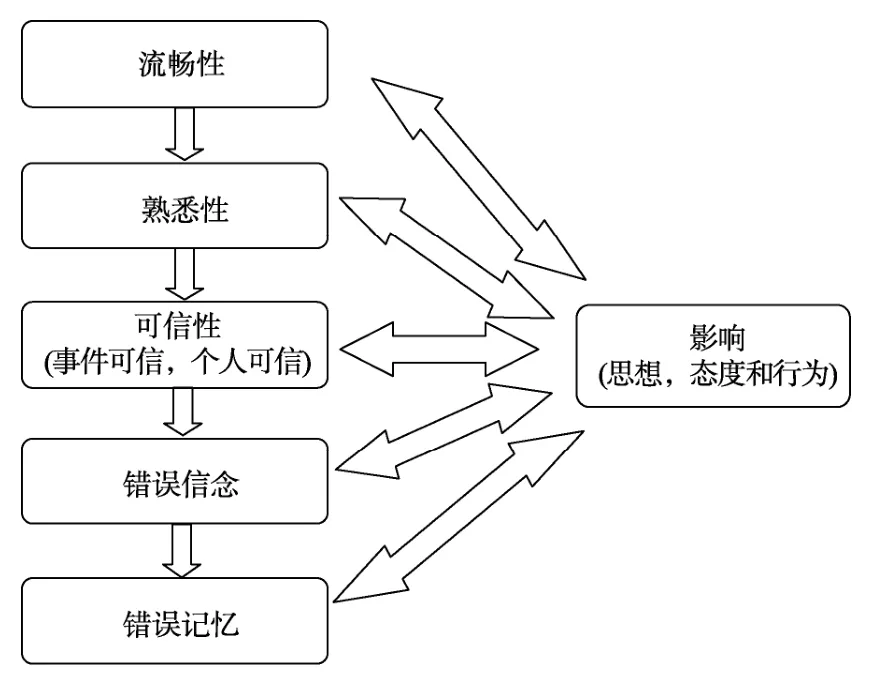

Markman, Klein和Suhr (2009)进一步扩展模型, 形成多阶段模型(multi-step model) (如图1)。此模型加入了植入性错误记忆的后续影响, 使其对植入性错误记忆做出了更加详细的诠释。他们认为, 个体相信植入的关键事件是可信的, 这依赖于人们对过去事件的加工速度, 即流畅性(fluency)。流畅性是对过去感知信息的一种整合连贯的良好形式。流畅性会受到刺激的重复性、清晰度以及呈现时间的影响。同时, 当人们无法意识到流畅性的来源时, 会把流畅性错误地归结于, 植入的关键事件是熟悉的。熟悉性(familiarity)能使人们错误地相信过去的某段虚假经历。而且,熟悉性会把植入性错误记忆归属于过去经历, 而不是错误反馈的结果(Bernstein, Whittlesea, &Loftus, 2002)。已往研究也证实, 熟悉性确实能引起被试对特定食物的态度及行为发生改变。Markman等(2009)认为, 在植入错误记忆的过程中, 流畅性与熟悉性先于可信性。而且, 当排除错误信念或记忆与行为之间的联系时, 单纯增加关键事件的可信性也能引起态度转变和行为结果(Scoboria et al., 2008)。

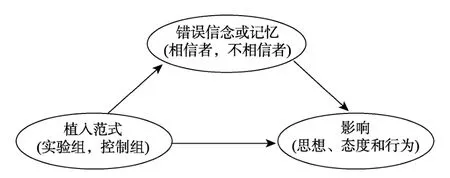

如果把植入范式、错误信念或记忆以及影响作为植入性错误记忆的三个变量, 可以构建出植入性错误记忆产生的中介模型(Bernstein, Pernat, & Loftus,2011) (图2)。不过, 这个模型的有效性尚需验证。

图1 植入性错误记忆形成的多阶段模型

图2 植入性错误记忆的中介模型

5 问题与回顾

5.1 要求特征

从已往研究可以看出, 植入的错误记忆可以影响人们的偏好、态度甚至行为。但被试是否会猜测实验目的, 并做出相应的行为来验证假设呢?即要求特征。例如, 被试表示出对特定食物的偏好及相应的行为改变, 只是为了做一名“好被试”。如果植入性错误记忆产生的行为是要求特征的结果, 那么植入的所有错误记忆都应该是有效的, 但对于普通食物而言, 植入错误记忆的效果却很小。没有证据显示, 社会赞许性以及受暗示性高的人更容易接受错误记忆。有研究者修改了实验程序, 采用“红鲱鱼”范式(转移注意力的话题), 隐藏了实验目的, 结果表明, 植入性错误记忆的行为结果并非是要求特征引起的(Laney,Kaasa et al., 2008)。

5.2 认知反应

既然错误记忆以及行为结果并不是要求特征的作用引起的, 那么, 它是一种认知反应, 还是一种直觉反应, 抑或是二者的结合?如果是一种认知反应, 被试进行偏好报告或产生行为时会仔细考虑目标食物并能回想错误信念或记忆。如果是一种直觉反应, 被试则会不假思索地作出反应。现有研究倾向认为, 错误记忆及其行为结果是认知反应的产物。

5.3 范式选取

植入范式会影响到植入效果。错误反馈技术和想象膨胀可以改变个体对新颖食物的态度以及行为倾向, 而对于普通食物的植入影响却很小。照片修改范式却能达到很好的效果(Wade et al.,2002)。对比研究发现, 照片修改范式并不比错误反馈技术和想象膨胀更有效, 但在特定事物上突显优势(Garry & Wade, 2005)。而想象与详细描述要比联结技术更有效(Baillie, Bernstein, &Greenwald, 2007)。可见, 不同范式的植入效果是不同的。因此, 如何有效选取研究范式仍然是一个值得考虑的问题。

5.4 实验伦理

错误记忆一旦被植入, 会影响人们的思想、态度以及行为, 并具有一定的持续性。实际上也很难把植入性错误记忆与真实记忆加以区分。因此, 当把植入性错误记忆的研究成果应用于实际生活时, 会面临很多实验伦理问题。例如, 不能公开宣称进行错误记忆的植入, 无疑会引起人们的抵触或防范。同时, 在不告之的情况, 以个人目的私自对他人植入错误记忆, 这也不符合实验伦理的要求。因此, 一种折中的办法是植入积极的错误记忆, 且在不影响植入效果的情况下, 给予被试一定的知情同意权(Bernstein & Loftus, 2009b)。

6 展望

植入性错误记忆的研究成果已经扩展到社会生活的许多方面, 如饮食调理、消费行为以及攻击行为等。可见, 植入性错误记忆未来研究的重点可能会倾向于解释植入性错误记忆如何影响我们的生活。但植入性错误记忆的研究还有许多不足和需要完善的地方, 今后研究应在以下几个方面进一步关注。

首先, 植入性错误记忆范式的有效性。从已往研究不难看出, 错误反馈技术或想象膨胀范式的成功植入率不足 30%, 照片修改范式的成功植入率也只有50%左右。Wade和Garry (2005)研究发现, 10个植入错误记忆研究的平均成功率大约是37%。因此, 在今后研究中, 应该在研究方法上有所改善, 或提出新的有效的植入错误记忆的范式, 以提高被试的利用率和成功植入率。

其次, 个体特征与植入性错误记忆的匹配。除研究方法外, 能否成功植入错误记忆还受到个体差异的影响, 如年龄(Otgaar, Candel, Merchelbach,& Wade, 2009)、性格(Porter, Birt, Yuille, & Lehman,2000; Takarangi, Polaschek, Hignett, & Garry, 2008;Vannucci, Nocentini, Mazzoni, & Menesini, 2012)及易感性(周楚, 2005)等。研究发现, 高分离经验、低消极评价、恐惧回避、高协调性、奖励依赖以及自主能力的个体会增加植入性错误记忆的敏感性(Hyman & Billings, 1998; Platt, Lacey, Jobs, &Finkelman, 1998; Wilson & French, 2006; Zhu et al.,2010a)。而高智力分数、高认知能力、高工作记忆容量以及高面孔再认表现的被试能有效地抵制错误记忆的植入(Gerrie & Garry, 2007; Zhu et al.,2010b)。可见, 不同个体对植入错误记忆的易感性是存在差异的。但个体特征对错误记忆的影响机制尚不清楚。

再次, 植入性错误记忆行为结果的测量。传统研究对行为结果的测量只是局限于行为倾向,而不是发生的具体行为。这很可能混淆了二者的区别(Greenwald et al., 2002)。虽然, 有研究已用具体行为代替行为倾向测验, 但其可行性还存在局限。因此, 未来对行为结果的研究应以具体的行为指标来进行测量。

最后, 植入性错误记忆的实际应用。错误记忆的植入性研究起初是围绕有关食物记忆的偏好与选择而展开, 因此, 可以通过植入错误记忆来改善饮食健康。调整饮食主要有两种方式:一种是增加对特定食物的偏好, 一种是增加对特定食物的厌恶。例如, 通过植入错误记忆的方法可以强化人们对芦笋的偏好(Laney, Morris et al., 2008)和酒精的厌恶(Clifasefi, Bernstein, Mantonakis, & Loftus,2013), 进而影响实际饮食行为。但需注意的是, 只有新颖食物才能有效植入错误记忆, 而普通食物植入错误记忆的效果并不明显(Bernstein, 2005b)。

总之, 通过适当的方法可以植入特定的错误记忆, 进而影响到人们的生活。关于植入性错误记忆的研究仍有许多值得深入探讨的问题, 但其学术价值和应用价值毋庸置疑。

周楚. (2005).错误记忆的理论和实验(博士学位论文). 华东师范大学, 上海.

Baillie, D. A., Bernstein, D. M., & Greenwald, A. G. (2007,May).The Food IAT: Examining food preference within the context of implicit association. Poster presented at Northwest Cognition and Memory, Vancouver, Canada.

Belli, R. F. (2012). Introduction: In the aftermath of the so-called memory wars. InTrue and false recovered memories(pp. 1–13). New York: Springer.

Berkowitz, S. R., Laney, C., Morris, E. K., Garry, M., &Loftus, E. F. (2008). Pluto behaving badly: False beliefs and their consequences.The American Journal of Psychology,121(4), 643–660.

Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F. (2009a). How to tell if a particular memory is true or false.Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(4), 370–374.

Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F. (2009b). The consequences of false memories for food preferences and choices.Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 135–139.

Bernstein, D. M., Laney, C., Morris, E. K., & Loftus, E. F.(2005a). False memories about food can lead to food avoidance.Social Cognition, 23(1), 11–34.

Bernstein, D. M., Laney, C., Morris, E. K., & Loftus, E. F.(2005b). False beliefs about fattening foods can have healthy consequences.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(39),13724–13731.

Bernstein, D. M., Pernat, N. L., & Loftus, E. F. (2011). The false memory diet: False Memories alter food preferences.InHandbook of behavior, food and nutrition(pp.1645–1663). New York: Springer.

Bernstein, D. M., Whittlesea, B. W., & Loftus, E. F. (2002).Increasing confidence in remote autobiographical memory and general knowledge: Extensions of the revelation effect.Memory & Cognition, 30(3), 432–438.

Brainerd, C. J., & Reyna, V. F. (2005).The science of false memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clancy, S. A. (2009a).The trauma myth: The truth about the

sexual abuse of children--and its aftermath. Basic Books.

Clancy, S. A. (2009b).Abducted: How people come to

believe they were kidnapped by aliens. Harvard University Press.

Clifasefi, S. L., Bernstein, D. M., Mantonakis, A., & Loftus,E. F. (2013). “Queasy does it”: False alcohol beliefs and memories may lead to diminished alcohol preferences.Acta Psychologica, 143(1), 14–19.

Davis, D., & Loftus, E. F. (2007). Internal and external sources of misinformation in adult witness memory. In M.P. Toglia, J. D. Read, D. F. Ross, & R. C. L. Lindsay (Ed.),The handbook of eyewitness psychology: Memory for events(pp. 195–237). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Foster, J. L., & Garry, M. (2012). Building false memories without suggestions.The American Journal of Psychology,125(2), 225–232.

Foster, J. L., Huthwaite, T., Yesberg, J. A., Garry, M., &Loftus, E. F. (2012). Repetition, not number of sources,increases both susceptibility to misinformation and confidence in the accuracy of eyewitnesses.Acta Psychologica, 139(2), 320–326.

Frenda, S. J., Knowles, E. D., Saletan, W., & Loftus, E. F.(2013). False memories of fabricated political events.Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(2), 280–286.

Gabbert, F., Memon, A., Allan, K., & Wright, D. B. (2004).Say it to my face: Examining the effects of socially encountered misinformation.Legal and Criminological Psychology, 9(2), 215–227.

Garry, M., & Wade, K. A. (2005). Actually, a picture is worth less than 45 words: Narratives produce more false memories than photographs do.Psychonomic Bulletin &Review, 12(2), 359–366.

Garry, M., Manning, C. G., Loftus, E. F., & Sherman, S. J.(1996). Imagination inflation: Imagining a childhood event inflates confidence that it occurred.Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3(2), 208–214.

Geraerts, E., Bernstien, D. B., Merckelbach, H., Linders, C.,Raymaekers, L., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Lasting false beliefs and their behavioral consequences.Psychological Science, 19(8), 749–753.

Gerrie, M. P., & Garry, M. (2007). Individual differences in working memory capacity affect false memories for missing aspects of events.Memory, 15(5), 561–571.

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Rudman, L. A., Farnham, S.D., Nosek, B. A., & Mellott, D. S. (2002). A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept.Psychological Review, 109(1), 3–25.

Gutchess, A. H., & Schacter, D. L. (2012). The neural correlates of gist-based true and false recognition.Neuroimage,59(4), 3418–3426.

Howard, D. J., & Kerin, R. A. (2011). Changing your mind about seeing a brand that you never saw: Implications for brand attitudes.Psychology & Marketing, 28(2), 168–187.

Hyman, I. E., Husband, T. H., & Billings, F. J. (1995). False memories of childhood experiences.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 9(3), 181–197.

Hyman, I. E., Jr., & Billings, F. J. (1998). Individual differences and the creating of false childhood memories.Memory, 6(1), 1–20.

Laney, C., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Emotional content of true and false memories.Memory, 16(5), 500–516.

Laney, C., & Takarangi, M. K. (2013). False memories for aggressive acts.Acta Psychologica, 143(2), 227–234.

Laney, C., Fowler, N. B., Nelson, K. J., Bernstein, D. M., &Loftus, E. F. (2008). The persistence of false beliefs.Acta Psychologica, 129(1), 190–197.

Laney, C., Kaasa, S. O., Morris, E. K., Berkowitz, S. R.,Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). The Red Herring technique: A methodological response to the problem of demand characteristics.Psychological Research, 72(4),362–375.

Laney, C., Morris, E. K., Bernstein, D. M., Wakefield, B. M.,& Loftus, E. F. (2008). Asparagus, a love story: Healthier eating could be just a false memory away.Experimental Psychology, 55(5), 291–300.

Loftus, E. F. (1975). Leading questions and the eyewitness report.Cognitive Psychology, 7(4), 560–572.

Loftus, E. F. (1997). Creating childhood memories.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 11(7), S75–S86.

Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory.Learning & Memory, 12(4), 361–366.

Loftus, E. F., & Bernstein, D. M. (2005). Rich false memories: The royal road to success. In A. F. Healy (Ed.),Experimental cognitive psychology and its applications(pp. 101–113). Washington DC: American psychological Association Press.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory.Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13(5), 585–589.

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories.Psychiatric Annals, 25(12), 720–725.

Loftus, E. F., & Davis, D. (2006). Recovered memories.Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 469–498.

Mantonakis, A., Bernstein, D. M. y Loftus, E. F. (2011).Attributions of fluency: Familiarity, preference, and the senses. En P. A. Higham J. P. Leboe (Eds.),Constructions of remembering and metacognition. Essays in honour of Bruce Whittlesea(pp. 40–50). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mantonakis, A., Wudarzewski, A., Bernstein, D. M.,Clifasefi, S. L., & Loftus, E. F. (2013). False beliefs can shape current consumption.Psychology, 4(3), 302–308.

Markman, K. D., Klein, W. M. P., & Suhr, J. A. (Eds.),(2009).The handbook of imagination and mental simulation(pp. 89–112). New York: Psychology Press.

Mazzoni, G. A., Loftus, E. F., & Kirsch, I. (2001). Changing beliefs about implausible autobiographical events: A little plausibility goes a long way.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 7(1), 51–59.

Mazzoni, G., & Memon, A. (2003). Imagination can create false autobiographical memories.Psychological Science,14(2), 186–188.

McNally, R. J., Lasko, N. B., Clancy, S. A., Maclin, M. L.,Pitman, R. K., & Orr, S. P. (2004). Psychophysiological responding during script-driven imagery in people reporting abduction by space aliens.Psychological Science, 15(7), 493–497.

Morgan III, C. A., Southwick, S., Steffian, G., Hazlett, G. A.,& Loftus, E. F. (2013). Misinformation can influence memory for recently experienced, highly stressful events.International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36(1), 11–17.

Morris, E. K., Laney, C., Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F.(2006). Susceptibility to memory distortion: How do we decide it has occurred?.The American Journal of Psychology,119(2), 255–274.

Otgaar, H., Candel, I., Merckelbach, H., & Wade, K. A.(2009). Abducted by a UFO: Prevalence information affects young children's false memories for an implausible event.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(1), 115–125.

Peters, M. J., Horselenberg, R., Jelicic, M., & Merckelbach,H. (2007). The false fame illusion in people with memories about a previous life.Consciousness and Cognition, 16(1),162–169.

Peterson, T., Kaasa, S. O., & Loftus, E. F. (2009). Me too!Social modeling influences on early autobiographical memories.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(2), 267–277.

Platt, R. D., Lacey, S. C., Jobs, A. D., & Finkelman, D.(1998). Absorption, dissociation, and fantasyproneness as predictors of memory distortion in autobiographical and laboratory-generated memories.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 12(7), 77–89.

Porter, S., Birt, A. R., Yuille, J. C., & Lehman, D. R. (2000).Negotiating false memories: Interviewer and rememberer characteristics relate to memory distortion.Psychological Science, 11(6), 507–510.

Porter, S., Yuille, J. C., & Lehman, D. R. (1999). The nature of real, implanted, and fabricated memories for emotional childhood events: Implications for the recovered memory debate.Law and Human Behavior, 23(5), 517–537.

Sacchi, D. L., Agnoli, F., & Loftus, E. F. (2007). Changing history: Doctored photographs affect memory for past public events.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(8), 1005–1022.

Schacter, D. L. (2002).The seven sins of memory: How the mind forgets and remembers. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Schacter, D. L., & Loftus, E. F. (2013). Memory and law:What can cognitive neuroscience contribute?.Nature Neuroscience, 16(2), 119–123.

Schacter, D. L., & Slotnick, S. D. (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of memory distortion.Neuron, 44(1), 149–160.

Scoboria, A., Mazzoni, G., & Jarry, J. L. (2008). Suggesting childhood food illness results in reduced eating behavior.Acta Psychologica, 128(2), 304–309.

Scoboria, A., Mazzoni, G., Jarry, J. L., & Bernstein, D. M.(2012). Personalized and not general suggestion produces false autobiographical memories and suggestion-consistent behavior.Acta Psychologica, 139(1), 225–232.

Scoboria, A., Mazzoni, G., Kirsch, I., & Relyea, M. (2004).Plausibility and belief in autobiographical memory.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18(7), 791–807.

Scott, S. (2001).The politics and experience of ritual abuse:Beyond disbelief. Open University Press.

Slotnick, S. D., & Schacter, D. L. (2004). A sensory signature that distinguishes true from false memories.Nature Neuroscience, 7(6), 664–672.

Slotnick, S. D., & Schacter, D. L. (2006). The nature of memory related activity in early visual areas.Neuropsychologia,44(14), 2874–2886.

Spanos, N. P., Burgess, C. A., Burgess, M. F., Samuels, C.,& Blois, W. O. (1999). Creating false memories of infancy with hypnotic and non-hypnotic procedures.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13(3), 201–218.

Stark, C. E., Okado, Y., & Loftus, E. F. (2010). Imaging the reconstruction of true and false memories using sensory reactivation and the misinformation paradigms.Learning& Memory, 17(10), 485–488.

Straube, B. (2012). An overview of the neuro-cognitive processes involved in the encoding, consolidation, and retrieval of true and false memories.Behavioral and Brain Functions, 8, 35.

Takarangi, M. K. T., Polaschek, D. L. L., Hignett, A., &Garry, M. (2008). Chronic and temporary aggression causes hostile false memories for ambiguous information.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22(1), 39–49.

Takarangi, M. K., Parker, S., & Garry, M. (2006).Modernising the misinformation effect: The development of a new stimulus set.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(5),583–590.

Vannucci, M., Nocentini, A., Mazzoni, G., & Menesini, E.(2012). Recalling unpresented hostile words: False memories predictors of traditional and cyberbullying.European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2), 182–194.

Wade, K. A., & Garry, M. (2005). Strategies for verifying false autobiographical memories.The American Journal of Psychology, 118(4), 587–602.

Wade, K. A., Garry, M., Read, J. D., & Lindsay, D. S. (2002).A picture is worth a thousand lies: Using false photographs to create false childhood memories.Psychonomic Bulletin &Review, 9(3), 597–603.

Wilson, K., & French, C. C. (2006). The relationship between susceptibility to false memories, dissociativity,and paranormal belief and experience.Personality and Individual Differences, 41(8), 1493–1502.

Wright, D. B., Self, G., & Justice, C. (2000). Memory conformity: Exploring misinformation effects when presented by another person.British Journal of Psychology,91(2), 189–202.

Zhu, B., Chen, C. S., Loftus, E. F., Lin, C. D., & Dong, Q.(2010). Treat and trick: A new way to increase false memory.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(9), 1199–1208.

Zhu, B., Chen, C. S., Loftus, E. F., He, Q. H., Chen, C. H.,Lei, X. M.,... Dong, Q. (2012). Brief exposure to misinformation can lead to long-term false memories.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(2), 301–307.

Zhu, B., Chen, C. S., Loftus, E. F., Lin, C. D., He, Q. H.,Chen, C. H.,... Dong, Q. (2010a). Individual differences in false memory from misinformation: Cognitive factors.Memory, 18(5), 543–555.

Zhu, B., Chen, C. S., Loftus, E. F., Lin, C. D., He, Q. H.,Chen, C. H., … Dong, Q. (2010b). Individual differences in false memory from misinformation: Personality characteristics and their interactions with cognitive abilities.Personality and Individual Differences, 48(8), 889–894.