体外扩增培养对兔脂肪来源干细胞的衰老及成骨分化能力的影响

2014-11-01张天媛于艳秋王晨超

张天媛, 郭 澍, 于艳秋, 王晨超, 孙 强

实验研究

体外扩增培养对兔脂肪来源干细胞的衰老及成骨分化能力的影响

张天媛, 郭 澍, 于艳秋, 王晨超, 孙 强

目的探讨体外扩增培养对兔脂肪来源干细胞的衰老及成骨分化能力的影响。方法分离提取兔脂肪来源干细胞,取第5、10、15代细胞进行成骨诱导,并采用茜素红染色法比较不同代数细胞的成骨能力,β-半乳糖苷酶染色法比较不同代数细胞的衰老程度。结果早期代数的细胞经成骨诱导后,出现矿化结节的时间较早,且在同一诱导时间下,与晚期代数的细胞相比,形成的结节数量最多、体积最大。随传代次数的增加,细胞外基质钙盐沉积量呈下降趋势,衰老细胞所占的比例呈上升趋势,差异具有统计学意义(P<0.05)。结论随体外扩增培养,兔脂肪来源干细胞成骨分化能力减弱,细胞发生衰老程度增强。

脂肪来源干细胞; 扩增; 衰老; 成骨

临床上因先天畸形、创伤及肿瘤等原因造成的颅颌面部骨性缺损,大大降低了患者的生活质量,骨缺损的重建是亟待解决的问题。骨组织工程的出现为骨缺损的修复开辟了一条新道路,其中脂肪来源干细胞(adipose-derived stem cells, ADSCs)作为新生的种子细胞,在组织工程的研究中得到了广泛的关注[1-4]。但是,有限的细胞数量需要体外扩增来培养一定量的细胞,供实验研究[5-6]。本实验于2013年9月,从兔的脂肪组织中提取出ADSCs,通过对其进行扩增培养,即长期传代,探讨体外扩增培养对兔ADSCs的衰老及成骨分化能力的影响,以期为基础研究提供理论支持,为临床应用提供优质的种子细胞。

1 材料与方法

1.1 标本来源

普通级健康4个月龄雌性新西兰大耳白兔6只,平均体质量4 kg,由中国医科大学动物部提供。

1.2 主要试剂和仪器

油红O染液、茜素红染液、氯化十六烷基吡啶(美国SIGMA公司);β-半乳糖苷酶染色试剂盒(武汉碧云天生物技术研究所);酶标仪(美国THEROMO公司)。

1.3 实验方法

1.3.1 兔ADSCs的分离提取、培养及实验分组 于兔臀部肌肉注射麻醉药后,在其颈背部行纵行切口,显露皮下脂肪,剪碎脂肪组织至糜状。将分离提取的ADSCs,接种于培养皿中,以1∶3传代,每2 d换液并观察细胞生长状态。实验分组: 将体外培养的ADSCs分成3组。A组:第5代ADSCs;B组:第10代ADSCs;C组:第15代ADSCs。每组实验重复6次。

1.3.2 ADSCs的多向诱导分化 成脂和成骨诱导组:当第3代的细胞达到80%~90%汇合后,分别更换成脂诱导液和成骨诱导液。成脂诱导3周,油红O染色鉴定其成脂分化能力[7]。成骨诱导4周,茜素红染色鉴定其成骨分化能力。成脂和成骨对照组:均常规培养[7]。

1.3.3 不同代数组ADSCs的成骨诱导分化 取第5、10、15代细胞,分别以相同密度接种于6孔板中,当细胞达到80%~90%汇合后,更换成骨诱导液。分别于成骨诱导的第1、2、3、4周,行茜素红染色及茜素红半定量分析[8]。

1.3.4 不同代数组ADSCs的衰老检测 取第5、10、15代的细胞,按照β-半乳糖苷酶原位染色试剂盒使用说明进行操作,分别检测不同代数组细胞的衰老程度,并随机选出500个细胞,倒置显微镜下观察并计算被染色的阳性细胞数,即为衰老细胞所占的百分数[9]。

1.4 统计学分析

2 结果

2.1 倒置显微镜下观察兔ADSCs的形态特征

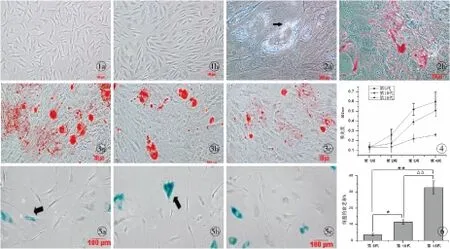

ADSCs培养24 h后,镜下可见大部分细胞已贴壁生长且呈宽大成纤维样,原代细胞培养至7 d左右,细胞达80%~90%汇合,此时进行传代培养。细胞传至第3代时,形态呈均一的长梭形,漩涡状生长(图1)。

2.2 ADSCs的多向诱导分化

成脂诱导组:细胞在成脂诱导液的作用下形成脂肪空泡,空泡被油红O染成红色(图2)。成骨诱导组:细胞在成骨诱导液的作用下形成矿化结节,矿化结节被茜素红染成橘红色。成脂和成骨对照组:无脂肪空泡及矿化结节形成。

2.3 不同代数组ADSCs的成骨诱导分化

茜素红染色:第5代的ADSCs经成骨诱导2周,便可出现矿化结节,当成骨诱导至第4周时,随传代次数的增加,形成的矿化结节不仅数量逐渐减少,且体积相应变小,其中第5代细胞形成的矿化结节数量最多,体积最大(图3)。

茜素红半定量分析:成骨诱导第1周时,第5、10、15代细胞的细胞外基质钙盐沉积量无统计学意义(P>0.05);诱导至第2周,第5代成骨诱导组的钙盐沉积量大于第10、15代诱导组,而第10代和第15代之间无统计学意义(P>0.05);诱导至第3、4周,两两组间比较均有统计学意义(P<0.05,图4)。

2.4 不同代数组ADSCs的衰老检测

随体外连续传代,细胞由典型的长梭形发展成不规则形态,体积变大、变扁,胞质中出现颗粒,细胞碎片增多,经β-半乳糖苷酶染色,衰老的细胞被染成蓝色。随传代次数的增加,被染色的衰老细胞增多(图5),镜下计数细胞衰老率升高(图6)。

3 讨论

ADSCs在组织工程的研究中越来越受到重视,若想成为理想的种子细胞,需要在保持其多向分化能力的情况下,经过体外的扩增培养,以供实验及临床需要[5-6]。Zuk等[10]认为,第15代之前的ADSCs,仍能保持其多向分化能力。Kang等[11]则持不同观点,认为12代之后的ADSCs其多向分化能力是逐渐下降的。而Wall等[12]却通过实验证实,10代之内的ADSCs在传代的后期其成骨分化能力开始逐渐增强 。目前,关于体外扩增培养是否会对干细胞的成骨分化能力产生影响,并未达成共识[10-15]。本实验从分子水平上研究体外扩增培养即长期传代对ADSCs成骨分化能力的影响,并且进一步探究细胞衰老与成骨分化能力之间可能存在的关系。

在成骨诱导实验中我们发现,不同代数组的细胞经过成骨诱导后,刚开始产生矿化结节的时间不同。第5代的ADSCs出现矿化结节的时间最早,成骨诱导2周就可有矿化结节出现,而第15代的细胞在诱导至第3周时才于细胞密集区看到少量的矿化结节。在相同的诱导时间下,随传代次数的增加,细胞形成矿化结节的数量逐渐减少,且体积相应变小。茜素红半定量检测细胞外基质钙盐沉积,成骨诱导1周后,第5、10、15代的ADSCs细胞外基质钙盐沉积量无统计学意义(P>0.05),当诱导至第2周,第5代成骨诱导组细胞的钙盐沉积量大于第10、15代诱导组,而第10代和第15代之间无统计学意义(P>0.05)。诱导至第3、4周,两两组间比较,均有统计学意义(P<0.05)。染色实验结合定量分析的结果表明,随着传代次数的增加,ADSCs成骨分化的能力减弱。学者们认为,体外扩增易导致细胞分子水平发生变化,而这种变化引起细胞增殖和分化能力的降低[16]。

图1 兔ADSCs的形态(倒置显微镜 ×100) a.原代ADSCs培养第7天 b.第3代ADSCs培养第5天图2 成脂诱导3周油红O染色结果(倒置显微镜 ×200) a.成脂诱导组形成的脂肪空泡(→) b.脂肪空泡被油红O染色图3 成骨诱导4周茜素红染色结果(倒置显微镜 ×100) a.第5代组 b.第10代组 c.第15代组图4 茜素红半定量检测细胞外基质钙盐沉积图5 β-半乳糖苷酶染色检测细胞衰老(→,倒置显微镜 ×100) a.第5代组 b.第10代组 c.第15代组图6 兔ADSCs衰老率检测*P<0.05,**P<0.01 第15代:第5代;ΔΔP<0.01 第15代:第10代

Fig1 Morphologies of rabbit ADSCs (Inverted microscope ×100) a. ADSCs of primary culture at 7 days. b. ADSCs of the third passage at 5 days.Fig2 Results of oil red O staining after adipogenic induction at 3 weeks (Inverted microscope,×200) a. formation of lipid vesicles in the adipogenic induction group (→). b. lipid vesicles stained by oil red O.Fig3 Results of alizarin red staining after osteogenic induction at 4 weeks (Inverted microscope ×100) a. the 5th passage group. b. the 10th passage group. c. the 15th passage group.Fig4 Extracellular matrix calcium mineralization detected by semiquantitative analysis of alizarin red.Fig5 Cell senescence detected by β-galactosidase stain (Inverted microscope ×100). a. the 5th passage group. b. the 10th passage group. c. the 15th passage group.Fig6 Detection of rabbit adipose-derived stem cells senescent rate.*P<0.05,**P<0.01 the 15th passage∶ the 5th passage;ΔΔP<0.01 the 15th passage∶ the 10th passage.

在细胞衰老的检测实验中,我们发现,随着体外传代扩增,细胞的形态由典型的长梭形发展成大而扁平的不规则形态,相同视野下被β-半乳糖苷酶染色的衰老细胞所占的比例逐渐升高,说明经过长期传代,兔ADSCs发生衰老的程度增强。探究细胞发生衰老的原因,学者们认为,主要和端粒长度、氧化应激和一些衰老相关基因的表达有关[17]。因此,衰老相关基因的高表达,可能在细胞的体外复制衰老中起到不可忽视的作用。

一项最新的研究结果表明,间充质干细胞发生衰老的过程不仅影响获得细胞的数量,同时也改变它们自我更新和多向分化的能力[18]。在骨髓间充质干细胞(bone marrow-derived stem cells, BMSCs)的研究中学者们发现,衰老的BMSCs其成骨和成脂的分化能力均是降低的[19-21]。随后,研究者们通过实验证实,正是由于基因表达的改变,才导致了衰老BMSCs的分化能力发生变化[22]。虽然ADSCs与BMSCs具有相似的生物学特性,但是目前关于衰老ADSCs多向分化能力的研究却鲜有报道。我们在实验中发现,随体外细胞大量传代扩增,兔脂肪干细胞成骨分化的能力下降,发生衰老的程度加大,但ADSCs成骨分化能力的下降与细胞复制衰老之间的相关性及机制有待我们更深入地研究。

[1] Tobita M, Orbay H, Mizuno H. Adipose-derived stem cells: current findings and future perspectives[J]. Discov Med, 2011,11(57):160-170.

[2] Buehrer BM, Cheatham B. Isolation and characterization of human adipose-derived stem cells for use in tissue engineering[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2013,1001:1-11.

[3] Declercq HA, De Caluwé T, Krysko O, et al. Bone grafts engineered from human adipose-derived stem cells in dynamic 3D-environments[J]. Biomaterials, 2013,34(4):1004-1017.

[4] Chen DC, Chen LY, Ling QD, et al. Purification of human adipose-derived stem cells from fat tissues using PLGA/silk screen hybrid membranes[J]. Biomaterials, 2014,35(14):4278-4287.

[5] Dao LT, Park EY, Hwang OK, et al. Differentiation potential and profile of nuclear receptor expression during expanded culture of Human adipose tissue-derived stem cells reveals PPARγ as an important regulator of Oct4 expression[J]. Stem Cells Dev, 2014,23(1):24-33.

[6] Mizuno H, Tobita M, Uysal AC. Concise review: adipose-derived stem cells as a novel tool for future regenerative medicine[J]. Stem Cells, 2012,30(5):804-810.

[7] Cheng NC, Wang S, Young TH. The influence of spheroid formation of human adipose-derived stem cells on chitosan films on stemness and differentiation capabilities[J]. Biomaterials, 2012,33(6):1748-1758.

[8] 李宇琳, 周 恒, 刘广鹏, 等. 茜素红半定量测定细胞基质钙含量的实验研究[J]. 组织工程与重建外科, 2008,4(2):61-64.

[9] Debacq-Chainiaux F, Erusalimsky JD, Campisi J, et al. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase(SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo[J]. Nat Protoc, 2009,4(12):1798-1806.

[10] Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies[J]. Tissue Eng, 2001,7(2):211-228.

[11] Kang SK, Putnam L, Dufour J, et al. Expression of telomerase extends the lifespan and enhances osteogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells[J]. Stem Cells, 2004,22(7):1356-1372.

[12] Wall ME, Bernacki SH, Loboa EG. Effects of serial passaging on the adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation potential of adipose-derived human mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Tissue Eng, 2007,13(6):1291-1298.

[13] Baer PC, Griesche N, Luttmann W, et al. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro: evaluation of an optimal expansion medium preserving stemness[J]. Cytotherapy, 2010,12(1):96-106.

[14] Park E, Patel AN. Changes in the expression pattern of mesenchymal and pluripotent markers in human adipose-derived stem cells[J]. Cell Biol Int, 2010,34(10):979-984.

[15] Safwani W, Zaman WK, Makpol S, et al. The changes of stemness biomarkers expression in human adipose-derived stem cells during long-term manipulation[J]. Biotechnolo Appl Biochem, 2011,58(4):261-270.

[16] Gimble JM, Guilak F, Bunnell BA. Clinical and preclinical translation of cell-based therapies using adipose tissue-derived cells[J]. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2010,1(2):19.

[17] Aran D, Toperoff G, Rosenberg M, et al. Replication timing-related and gene body-specific methylation of active human gen-es[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2011,20(4):670-680.

[18] Alt EU, Senst C, Murthy SN, et al. Aging alters tissue resident mesenchymal stem cell properties[J]. Stem Cell Res, 2012,8(2):215-225.

[19] Dar A, Domev H, Ben-Yosef O, et al. Multipotent vasculogenic pericytes from human pluripotent stem cells promote recovery of murine ischemic limb[J]. Circulation, 2012,125(1):87-99.

[20] Wagner W, Horn P, Castoldi M, et al. Replicative senescence of mesenchymal stem cells: a continuous and organized proce-ss[J]. Plos One, 2008,3(5):e2213.

[21] Wagner W, Ho AD, Zenke M. Different facets of aging in human mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Tissue Eng Part B Rev, 2010,16(4):445-453.

[22] Cheng H, Qiu L, Ma J, et al. Replicative senescence of human bone marrow and umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation to adipocytes and osteoblasts[J]. Mol Biol Rep, 2011,38(8):5161-5168.

Effectofamplifiablecultivationinvitroonsenescenceandosteogenesisofrabbitadipose-derivedstemcells

ZHANGTian-yuan,GUOShu,YUYan-qiu,etal.

(DepartmentofPlasticSurgery,FirstAffiliatedHospitalofChineseMedicalUniversity,Shenyang110001,China)

ObjectiveTo study the effect of amplifiable cultivation in vitro on senescence and osteogenesis of rabbit adipose-derived stem cells.MethodsRabbit adipose-derived stem cells were isolated from rabbits. The 5th, 10th and 15th passage of cells were harvested for the Alizarin red stained and β-galactosidase stained to compare the osteogenesis and cell senescence among different passage cells, respectively.ResultsThose cells of early passages had mineralized nodules earlier, which the nodules were the most and largest than the late passages cells. The extracellular matrix calcium mineralization decreased and the senescent cells accounted for an increasing proportion with the increase of cell passages,and the differences were statistically significant (P<0.05).ConclusionWith the amplification in vitro, the abilities to induce osteogenic differentiation are reduced and the degree of senescence increase in the rabbit adipose-derived stem cells.

Adipose-derived stem cells; Amplification; Senescence; Osteogenesis

国家自然科学基金资助项目(51272286),辽宁省自然科学基金资助项目(20102296)

110001 辽宁 沈阳,中国医科大学附属第一医院 整形外科(张天媛,郭 澍,王晨超,孙 强);中国医科大学基础医学院 病理生理教研室(于艳秋)

张天媛(1985-),女,黑龙江齐齐哈尔人,硕士研究生.

郭 澍,110001,中国医科大学附属第一医院 整形外科,电子信箱:guoshu67@sohu.com

10.3969/j.issn.1673-7040.2014.08.016

R-322;R318

A

1673-7040(2014)08-0492-04

2014-05-10)