The changing landscape of mangroves in Bangladesh compared to four other countries in tropical regions

2014-04-19MijanUddinRafiqulHoqueSaifulArifAbdullah

S.M.Mijan Uddin • A.T.M.Rafiqul Hoque • Saiful Arif Abdullah

Introduction

The transformation and degradation of tropical forests is thought to be one of the major components of the carbon cycle.It has profound implications with detrimental consequences for the natural resources (including biological resources) of the landscape (Sánchez-Azofeifa et al.2003; Viña et al.2004).Here, landscape refers to a mosaic of heterogeneous vegetation types, shapes and land use (Jorge 1997).The management of landscapes for biological conservation and ecologically sustainable natural resource use are crucial global issues (Lindenmayer et al.2008).Landscape change through forest loss and fragmentation increases atmospheric CO2and other trace gases (Skole and Tucker 1993; Houghton 2003; Cayuela et al.2006).

Mangroves are the inter-tidal wetlands of the tropical and sub-tropical coastlines.Though they occupy small area, they are highly productive ecosystems.Unfortunately the protective, productive, and ecological roles of these mangroves are not duly acknowledged.The Sundarbans and Chakaria Sundarbans represent natural mangroves in Bangladesh.The Sundarbans spreading over the southern part of Bangladesh and Pashchim Banga (formerly known as West Bengal state of India) is the largest single continuous patch of productive mangrove forest of the world.Malaysia is one of the 14 major deforesting countries with over 250,000 ha lost annually (McMorrow and Talip 2001).By 2005, about 16.2% of the total mangrove of Malaysia was gone over the last 25 years (FAO 2007).

Extensive aquaculture production has led to widespread mangrove destruction in all tropical regions of the world (Páez-Osuna 2001).The impacts of aquaculture on mangrove forests are estimated to be considerable, especially in Asia, where an estimated 1 million ha of coastal lowlands have been converted for shrimp aquaculture (Páez-Osuna 2001).Though shrimp ponds in Malaysia dominate the coastal aquaculture, the rate of increase in fish cage farming is nearly six times faster than the growth of shrimp ponds (Alongi et al.2003).Alonso-Perez (2003) reported that, the development of shrimp aquaculture had changed the coastal landscape covering 3,190 ha in less than 15 years.

Conversion of mangroves to other land uses can increase shoreline erosion and adversely affect biogeochemical and hydrological cycles that regulate water quality, offer flood protection and moderate climate (Ismail 1995; Seto and Fragkias 2007).These trends have been widely covered in the national and international press but precise and appropriate research based on scientific data does not receive much coverage.The present study is an effort to investigate the changing mangrove forests in Bangladesh and to compare our findings with four other countries, India, Myanmar, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

Materials and methods

To gain a global perspective of mangrove distribution (Figs 1 and 2), the research team examined collections of secondary information and visited several libraries, including Chittagong University, University of the Ryukyus Japan, National University of Malaysia, Bangladesh Forest Department (Bon Bhobon, Dhaka), Bangladesh Forest Research Institute.Information was also gleaned from refereed journals, books, and publications.

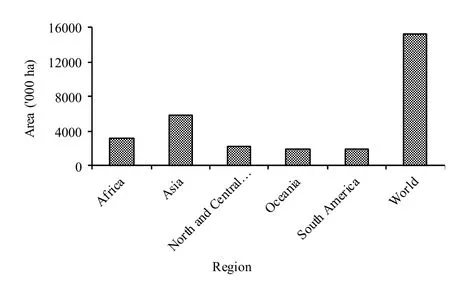

Fig.1: Most recent estimates of mangrove in different regions of the world

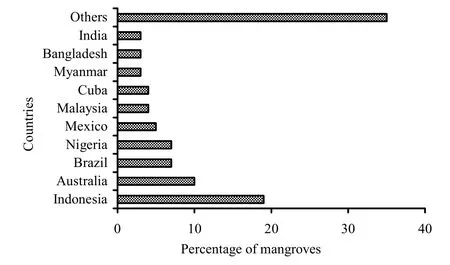

Fig.2: Percentage of world mangrove in top ten countries

For the study, five major countries Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Malaysia and Indonesia were selected because they have the largest mangrove areas (Figs.3 and 4).Field visits were carried out in these countries, especially in Bangladesh and Malaysia.Information on mangroves in India, Myanmar and Indonesia were compiled from secondary sources (FAO 2007) and through informal interview from renowned scientists from those countries.

Fig.3: Mangrove dominated countries in Asia [Black rectangle represents countries with highest mangrove areas

Fig.4: Mangrove areas of five major dominant tropical countries in Asia

The changing trends in mangrove areas (the annual changing rate of mangrove forest), r was calculated using the compound interest rate due to its explicit biological implications (Puyravaud 2003).

where, A1and A2are the area under forest cover at time t1and t2。

Results and discussion

Distribution of mangroves around the world

Mangroves are distributed latitudinally within the tropics and subtropics reaching their maximum development between 25°N to 25°S.Climatic factors such as temperature and moisture affect mangrove distribution.In some areas, coastal processes like tidal mixing and coastal currents may also influence mangrove distribution.The richest mangrove communities occur in areas where the water temperature is greater than 24°C in the warmest month.Mangrove ecosystems are estimated to cover 181,000 km2worldwide (Spalding et al.1997).

Some 15.2 million hectares of mangroves are estimated to exist worldwide as of 2005, down from 18.8 million hectares in 1980 (FAO 2007).The most extensive mangrove area is found in Asia, followed by Africa and North and Central America (Fig.1).Five countries (Indonesia, Australia, Brazil, Nigeria, and Mexico) together account for 48 percent of the total global mangroves and 65 percent of the total mangrove area is found in just 10 countries (Fig.2).The remaining 35 percent is spread over 114 countries and areas, of which 60 have less than 10,000 ha of mangrove each (FAO 2007).

Drivers of change in particular to mangrove

The greatest concentration (41.5%) of the world’s 18 million hectares of mangroves exists in Asia, and Southeast Asia has the widest expanse (at least one million ha) of brackish water aquaculture ponds (Primavera 2000).Most of the mangrove areas in the region have been degraded and denuded at an unprecedented rate.Global and regional attention is required to conserve the remaining mangroves because of land-use changes accompanying economic growth and urban settlement expansion in coastal areas of the region (Samarakoon 2004).However, the causes of mangrove depletion vary from country to country (Siddiqi 2001).Proximate causes are human activities or immediate actions at the local level that originate from intended land use and directly impact forest cover (Lambin et al.2001).Different proximate and underlying driving forces are found responsible for tropical deforestation (Contreras-Hermosilla 2000; Geist and Lambin 2002).The most prominent drivers of mangrove destruction in the selected region are shrimp aquaculture, infrastructure extension, agricultural expansion, wood extraction, natural causes, and construction of dams (Table 1).

Table 1: Drivers of mangrove destruction

In many countries, large-scale conversion of mangroves was carried out for aquaculture facilities.In the southwest part of Bangladesh, one of the oldest mangrove forests of the subcontinent, the ‘Chakaria Sundarbans’ had an area of 6020 ha in 1972, which was completely destroyed in 1989 (Akhter 2011) as consequence of human intervention, including as salt production and shrimp aquaculture.The key objectives of the Bangladesh forestry sector are to bring forests under sustainable management.The construction of infrastructure in the mangrove forest could destroy the mangrove forest and make the area most vulnerable to natural disasters.

Shrimp aquaculture was found to be an important cause of the conversion of mangroves in India in the last decades (Hein 2000).Besides, large aquaculture schemes critically threaten the existing mangroves in Malaysia (Ong 1982).Furthermore, rapid industrial development and urbanization in the region during the past two decades have given rise to the increased quantity and diversity of toxic and hazardous wastes on coastal resources (Abdullah 1995; Oo 2002).In Thailand, 55% of the country’s mangroves were converted to aquaculture between 1961 and 1993 (Seto and Fragkias 2007).In the Philippines, approximately about 70% mangroves were lost from 1918 to 1987 to accommodate the aquaculture industry (Triño and Rodriguez 2002).

The underlying forces are fundamental social processes that underpin the proximate causes and either operate at the local level or have an indirect impact from the national or global level (Geist and Lambin 2002).Overlapping bureaucracy and conflicting policies were found to be the dominant underlying social driving forces in the selected countries (Lambin et al. 2001).In Myanmar, mangrove forests have been rapidly denuded and deforested due to population pressure and political instability that caused environmental and economic damage and threatened recovery (Oo 2002).Lack of awareness or public education (Sarkar and Bhattacharya 2003) and good governance to implement sustainable resource conservation and environmental protection activities at grass root level could exacerbate all other driving forces of mangrove destruction (Hsiang 2000; Kumar 2000).

The adoption of Bangladesh’s Coastal Zone Policy of 2005 has brought about successful integrated coastal zone management (Iftekhar 2006).The adopted management measures not only contribute to forestry resource management but also to the social, environmental and economic wellbeing of the coastal communities.These efforts are, at present, being integrated into an integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) project (Iftekhar and Islam 2004a, b).

Forest decline in Sabah, Malaysia has resulted from state policies operating within the federal context.Commercial estate agriculture, especially oil palm, is now the major cause of forest loss, aided by Sabah's land-tenure code and the ethnic equality and modernization agendas of national and state agriculture policy (McMorrow and Talip 2001).The alternative mangrove land uses should only be judged after taking into account the environmental subsidies involved and possible losses through land-use changes (Marshal 1994).To arrest the continued degradation allowed by conventional forest management flaws, adaptive co-management could be recommended to conserve this ecosystem in a more equitable way (Iftekhar and Takama 2008).

Trends and changes of mangroves in Bangladesh comparing other countries

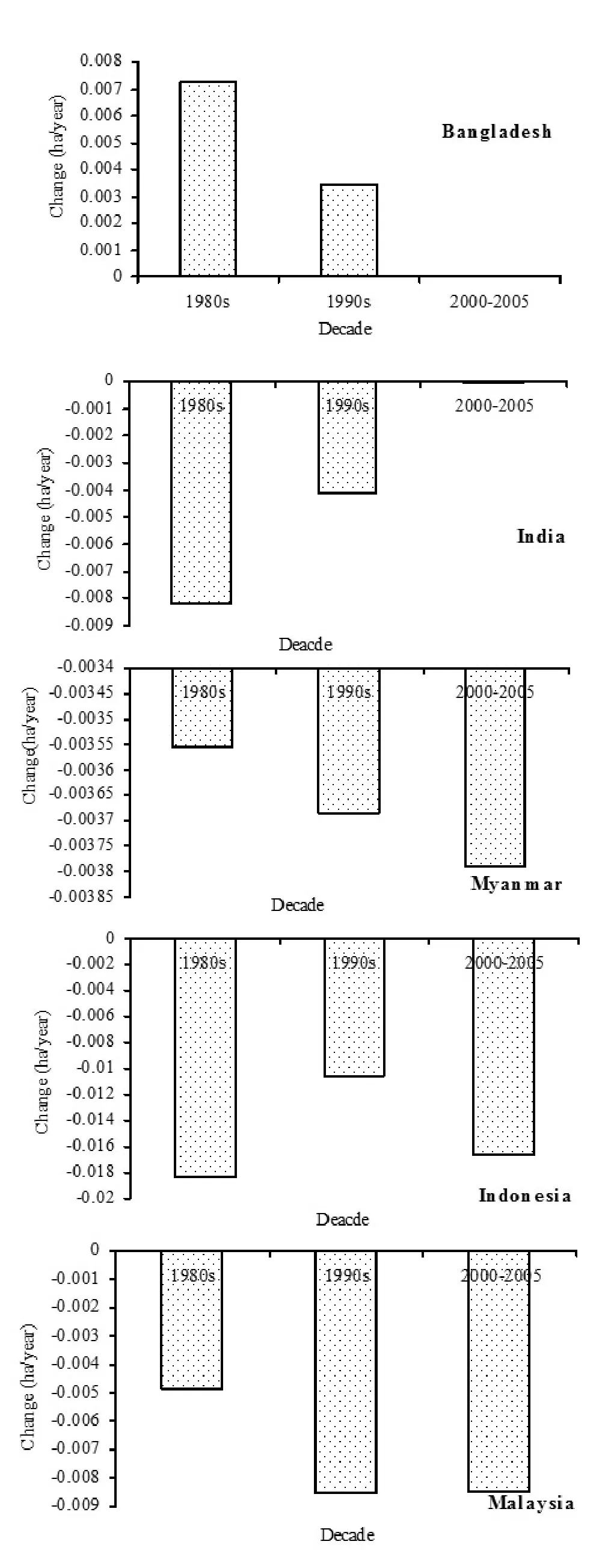

The rate of change as well as its trends in the study area is shown in Figs.5 and 6.The rate of mangrove landscape change in Bangladesh has decreased compared to earlier decades.Mangrove areas are decreasing, in particular the Chakaria Sundarbans and the Sundarbans mangrove forest (Iftekhar and Islam 2004b; Akhter et al.2009).However the study did not consider the rate of accretion in the coastal region that obviously lead to the increase of the mangrove landscape as a whole.Hence the area of mangroves was increased due to its higher accretion rate.In India, the rate of mangrove loss was decreased.The major reason for this trend is probably be the absence of agricultural expansion as a driver of mangrove change and present good governance (Table 1).

The rate of mangrove loss in Malaysia in the 1990s (-0.008 ha·a-1) was higher than that of the 1980s (-0.004 ha·a-1).In Malaysia, palm oil expansion as an agricultural activity was one of the major drivers behind the higher losses in recent decades.The rate was higher in 1980s (-0.018 ha·a-1) than that in 1990s (-0.010 ha·a-1) in Indonesia, whereas, in Myanmar the rate of mangrove loss gradually accelerated and aquaculture is the main reason.Coastal encroachment and weak governance are other important driving forces for mangrove landscape destruction.

Fig.5: Rate of change from 1981-2005: Changing landscape of mangrove areas (ha·a-1)

Fig.6: Trends of changes of mangrove areas (ha) from 1980 to 2005

Major reasons for mangrove area increase in Bangladesh

The degradation of the Sundarbans has been raised in recent decades (Karim 1994, 1995; IUCN Bangladesh 2001; Siddiqi 2001).Iftekhar and Islam (2004b) mentioned reduction in the extent of forest cover as one of the reasons of degradation.Prior to 1870, reliable estimates of the aerial extent of the Sundarbans forest are not available.Available literature supports that during 1873–1933 the forest has been reduced from 7,500 km2to 6,000 km2(Curtis 1933; Blasco 1977).Until then the boundary of the forest remained almost unchanged (Iftekhar and Islam 2004b).Vegetation inventories of the forest show that the aerial extent of the tree coverage has been reduced by 0.04% per year during the period 1926/28–1995.

However, data on all the measured vegetation characteristics are not directly comparable due to methodological differences in the vegetation inventories (Canonizado and Hossain 1998; FAO 1998).Besides, Akhter et.al.(2009) reported that the Chakaria Sundarbans mangrove forest areas have been shrinking in Bangladesh.They found that the natural mangrove of Chakaria Sundarbans was covering an area of 6,020 ha.in 1972, which was completely destroyed in 1989, except for a few patches of mangrove plantations in the newly accreted lands where the Bangladesh Forest Department had initiated plantation programs to rehabilitate the mangrove ecosystem along the coastal belts.Field investigations in 1999 showed only about 20 percent of the total plantations were remnants of the newly accreted lands (Akhter et.al.2009).

Knowledge on how fluvial and marine sediments behave and are retained in the area is important for the long-term development of the coastal area.Huge amounts of sediments carried by the flow are deposited in the channels and on the tidal mud flats, mangroves, and salt marshes, compensated by quite similar eroded amounts from the banks of channels where sediments are being picked up and further transported (Islam 2004).

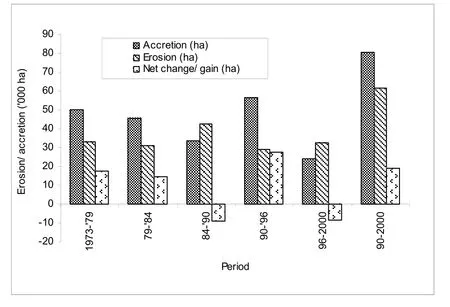

Land erosion and accretion are common natural phenomena in the coastal zone.Excluding intertidal erosion and accretion, the overall land gain for the Meghna estuary system was 50,800 ha (Fig.7).The average annual gain for the entire study period was 1880 ha·a-1(Islam 2004).Bangladesh has one of the largest mangrove plantation programs in the world.Over the last four decades, the Forest Department has successfully implemented several massive projects and has established more than 148,000 hectares of mangrove plantations scattered over on and offshore areas, mostly along the central part of the coast.So, besides the huge land gain from accretion of coastal areas, government initiative for plantations is the major reason for increasing mangrove areas in Bangladesh.

Conclusion

Mangroves are disappearing worldwide by 1 to 2 percent per year, a rate greater than or equal to declines in adjacent coral reefs or tropical rainforests (FAO 2003; Stone 2007).In developing countries, the losses are occurring at an alarming rate.Over the last quarter century, mangrove losses range consistently between 35 and 86% (Duke et al.2007).The number of plant species is sometimes directly correlated with forest size (Duke et al.1998; Ellison 2002).Loss of mangroves has been associated with prominent global issues, including loss of biodiversity, deterioration of habitat integrity, climatic changes through alteration in the rate of evapo-transpiration, the amount of carbon sequestration and the resulting sea-level rise.Obviously destruction of mangroves will decrease of species richness and result in declining forest services.Species extinction will be followed by the reduction of a huge carbon sink.Both terrestrial and aquatic food webs will be destroyed.People’s dependence on forest would be deprived of the resources they have been enjoying in particular environmental protections from strong wind and tidal surges.

Fig.7: Summery of erosion and accretion in the Meghna Estuary During 1973- 2000 (MES, 2001)

Restoration of mangrove forests must be done to combat the growing pressures of urban and industrial developments along coastlines, combined with climate change and sea-level rise.We need to reverse the trend of mangrove loss and ensure that future generations enjoy the ecosystem services provided by such valuable natural resources.Good governance and wise policy decisions will be necessary to halt massive mangrove destruction.At the same time, a systematic evaluation of environmental impacts throughout the mangrove region is the prerequisite for reaching sustainable mangrove management.

Acknowledgement

This study was partially funded by the research grant number UKM-GUP-ASPL-08-06-212.The authors are grateful to Forest Research Institute of Malaysia (FRIM) for providing much-needed information.Special thanks go to Dr.Analuddin, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Haluoleo University, Kendari, Indonesia and Mr.S.Sharma, a former research fellow, ISRO, Ahmedabad, India, for providing necessary information regarding mangroves in Indonesia and India respectively.

Abdullah AR.1995.Environmental pollution in Malaysia: trends and prospects.Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 14(5): 191−198.

Akhter M, Alam MJ, Hossain M.2009.Identification of Forest Cover Change (1972-1999) of Chakaria Sundarbans, Bangladesh using Landsat imagery.Asian Journal of Geoinformatics, 9(3): 11−14.

Alongi DM, Chong VC, Dixon P, Sasekumar A, Tirendi F.2003.The influence of fish cage aquaculture on pelagic carbon flow and water chemistry in tidally dominated mangrove estuaries of peninsular Malaysia.Marine Environmental Research, 55: 313−333.

Alonso-Perez F, Ruiz-Luna A, Turner J, Berlanga-Robles CA, Mitchelson-Jacob G.2003.ALand cover changes and impact of shrimp aquaculture on the landscape in the Ceuta coastal lagoon system, Sinaloa, Mexico.Ocean and Coastal Management, 46: 583−600.

Billah AHMM.2003.Green accounting- tropical experience.Dhaka: Palok publishers, p.357.

Blasco F.1977.Outlines of ecology, botany and forestry of the mangals of the Indian subcontinent.In: VJ Chapman (ed.), Wet coastal ecosystems, ecosystems of the world, 1.Amsterdam: Elsevier Scientific Publishing, pp 241−260.

Canonizado JA, Hossain MA.1998.Integrated forest management plan for the Sundarbans reserved forest.Mandala Agricultural Development Corporation and Forest Department and Ministry of Environment and Forest, Bangladesh.

Cayuela L, Benayas JMR, Echeverría C.2006.Clearance and fragmentation of tropical montane forests in the Highlands of Chipas, Mexico (1975-2000).Forest Ecology and Management, 226: 208−218.

Contreras-Hermosilla A.2000.The underlying causes of forest decline.CIFOR Occasional Paper No.30.Center for International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia.

Curtis SJ.1933.Working plan for the forests of the Sundarbans division (April 1931 to March 1951).Calcutta: Bengal Government Press.

Duke NC, Ball MC, Ellison JC.1998.Factors influencing in mangroves.Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters, 7: 27-47.

Duke NC, Meynecke JO, Dittmann S, Ellison AM, Anger K, Berger U, Cannicci S, Diele K, Ewel KC, Field CD, Koedam N, Lee SY, Marchand C, Nordhaus I, Dahdouh-Guebas F.2007.A world without mangroves? Science, 317: 41−42.

Ellison AM.2002.Macroecology of mangroves: large-scale patterns and processes in tropical coastal forests.Trees Structure and Function, 16: 181−194.

FAO.1998.Summary of the integrated resources management plan of the Sundarbans Reserved Forest.Project BGD/84/ 056, Integrated Resource Development of the Sundarbans Reserved Forest, Forest Department, Khulna, Bangladesh and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO.2003.Status and trends in mangrove area extent worldwide.Paris: Forest Resources Division, The Food and Agriculture Organization.

FAO.2007.The world’s mangroves 1980-2005.FAO Forestry Paper 153, Rome, p.77.

Geist HJ, Lambin EF.2002.Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation.BioScience, 55(2): 143−150.

Hein L.2000.Impact of shrimp farming on mangroves along India’s East Coast.Unasylva, 51(203): 48−54.

Houghton RA.2003.Revised estimates of the annual net flux of carbon to the atmosphere from changes in land use and land management 1850-2000.Tellus, 55B(2): 378−390.

Hsiang LL.2000.Mangrove conservation in Singapore: a physical or psychological impossibility? Biodiversity and Conservation 9: 309−332.

Iftekhar MS, Islam MR.2004a.Managing mangroves in Bangladesh: A strategy analysis.Journal of Coastal Conservation, 10: 139-146.

Iftekhar MS, Islam MR.2004b.Degeneration of Bangladesh’s Sundarbans mangroves: a management issue.International Forestry Review, 6(2): 123−135.

Iftekhar MS, Takama T.2008.Perceptions of biodiversity, environmental services, and conservation of planted mangroves: A case study on Nijhum Dwip Island, Bangladesh.Wetlands Ecology and Management, 16: 119−137.

Iftekhar MS.2006.Conservation and management of the Bangladesh coastal ecosystem: Overview of an integrated approach.Natural Resources Forum, 30: 230–237

Islam MR (ed).2004.Where land meets the sea? A profile of the coastal zone of Bangladesh.Dhaka: The University Press Limited, p.192.

Islam MS, Wahab MA.2005.A review on the present status and management of mangrove wetland habitat resources in Bangladesh with emphasis on mangrove fisheries and aquaculture.Hydrobiologia, 542: 165−190.

Ismail R.1995.An economic evaluation of carbon emission and carbon sequestration for the forestry sector in Malaysia.Biomass and Bioenergy, 8(5): 285−292.

IUCN-Bangladesh.2001.The Bangladesh Sundarbans: A photoreal sojourn.Dhaka, Bangladesh: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office.

Jorge LAB.1997.A study of habitat fragmentation in Southern Brazil using remote sensing and geographic information systems (GIS).Forest Ecology and Management, 98: 35−47.

Karim A.1994.Vegetation.In: Hussain Z, Acharya G.(eds.), Mangroves of the Sundarbans, Volume Two: Bangladesh.IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand.

Karim A.1995.Report on mangrove siliviculture, volume 1.Integrated Resource Development of the Sundarbans Reserved Forest, FAO/UNDP Project BGD/84/056, United Nations Development Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Kathiresan K.2000.A review of studies on Pichavaram mangrove, southeast India.Hydrobiologia, 430: 185−205.

Kumar R.2000.Conservation and management of mangroves in India, with special reference to the State of Goa and the Middle Andaman Islands.Unasylva, 203(51): 41−47.

Lambin EF, Turner BL, Geist HJ, Agbola SB, Angelsend A, Bruce JW, Coomes OT, Dirzo R, Fischer G, Folke C, George PS, Homewood K, Imbernon J, Leemans R, Li X, Moran EF, Mortimore M, Ramakrishnan PS, Richards JF, Skånes H, Steffen W, Stone GD, Svedin U, Veldkamp TA, Vogel C, Xu J.2001.The causes of land-use and land-cover change: moving beyond the myths.Global Environmental Change, 11: 261–269.

Lindenmayer D, Hobbs RJ, Montague-Drake R, Alexandra J, Bennett A, Burgman M, Cale P, Calhoun A, Cramer V, Cullen P, Driscoll D, Fahrig L, Fischer J, Franklin J, Haila Y, Hunter M, Gibbons P, Lake S, Luck G, MacGregor C, McIntyre S, Nally RM, Manning A, Miller J, Mooney H, Noss R, Possingham H, Saunders D, Schmiegelow F, Scott M, Simberloff D, Sisk T, Tabor G, Walker B, Wiens J, Woinarski J, Zavaleta E.2008.A checklist for ecological management of landscapes for conservation.Ecology Letters, 11: 78−91.

Marshall N.1994.Mangrove conservation in relation to overall environmental considerations.Hydrobiologia, 285: 303−309.

McMorrow J, Talip MA.2001.Decline of forest area in Sabah, Malaysia: relationship to state policies, land code and land capability.Global Environmental Change, 11: 217−230.

MES.2001.Hydromorphological dynamics of the Meghna estuary.Meghna Estuary Study Project, Bangladesh Water Development Board, Ministry of Water Resources of Bangladesh.Dhaka, June 2001

Ong JE.1982.Mangroves and aquaculture in Malaysia.Ambio, 11(5): 252−257.

Ong JE.2004.The ecology of mangrove conservation and management.Hydrobiologia, 295: 343−351.

Oo NW.2002.Present state and problems of mangrove management in Myanmar.Trees, 16: 218−223.

Páez-Osuna F.2001.The environmental impact of shrimp aquaculture: A global perspective.Environmental Pollution, 112: 229−231.

Primavera, JH.2000.The values of wetlands: landscape and institutional perspectives.Development and conservation of Philippine mangroves: institutional issues.Ecological Economics 35: 91−106.

Puyravaud JP.2003.Standardizing the calculation of the annual rate of deforestation.Forest Ecology and Management, 177: 593−596.

Samarakoon J.2004.Issues of livelihood, sustainable development and governance: Bay of Bengal.Ambio, 33: 34-44.

Sánchez-Azofeifa GA, Daily GC, Pfaff ASP, Busch C.2003.Integrity and isolation of Costa Rica’s national parks and biological reserves: examining the dynamics of land cover change.Biological Conservation, 109: 123−135.

Sarkar SK, Bhattacharya AK.2003.Conservation of biodiversity of the coastal resources of Sunderbans, Northeast India: an integrated approach through environmental education.Marine Pollution Bulletin, 47: 260−264.

Seto KC, Fragkias M.2007.Mangrove conversion and aquaculture development in Vietnam: A remote sensing-based approach for evaluating the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.Global Environmental Change, 17: 486−500.

Siddiqi NA.2001.Mangrove forestry in Bangladesh.Institute of forestry and Environmental Sciences, University of Chittagong.201 pp.

Skole D, Tucker C.1993.Tropical deforestation and habitat fragmentation in the Amazon: satellite data from 1978-1988.Science, 260: 1905−1910.Spalding MD, Blasco F, Field CD.1997.World Mangrove Atlas.Okinawa, Japan: The International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems, p.178.

Stone R.2007.A world without corals? Science, 316: 678−681.

Triño AT, Rodriguez EM.2002.Pen culture of mud crab Scylla serrata in tidal flats reforested with mangrove trees.Aquaculture, 211: 125−134.

Viña A, Echavarria FR, Rundquist DC.2004.Satellite change detection analysis of deforestation rates and patterns along the Colombia- Ecuador Border.Ambio, 33(3): 118−125.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Ethno-medicinal plants used by Bengali communities in Tripura, northeast India

- Litter production, decomposition and nutrient mineralization dynamics of Ochlandra setigera: A rare bamboo species of Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, India

- Temporal changes in nitrogen acquisition of Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii) associated with black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)

- Plant diversity at Chilapatta Reserve Forest of Terai Duars in subhumid tropical foothills of Indian Eastern Himalayas

- Floristic composition and management of cropland agroforest in southwestern Bangladesh

- The effect of fire disturbance on short-term soil respiration in typical forest of Greater Xing’an Range, China