晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期影响因素的相关性分析

2013-06-09

复旦大学附属肿瘤医院综合治疗科,复旦大学上海医学院肿瘤学系,上海 200032

晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期影响因素的相关性分析

顾筱莉 成文武

复旦大学附属肿瘤医院综合治疗科,复旦大学上海医学院肿瘤学系,上海 200032

背景与目的:晚期恶性肿瘤的预后判断在肿瘤治疗领域中非常重要,预后判断准确可以帮助临床医师选择相关的治疗。本研究旨在探讨接受姑息治疗的晚期恶性肿瘤患者的生存期相关影响因素,以期更好的指导临床。方法:回顾性分析2007年3月—2012年3月复旦大学附属肿瘤医院姑息治疗科271例死亡患者临床资料。应用Kaplan-Meier计算生存期,Log-rank检验差异性,并行Cox模型多因素分析,建立预后指数方程。结果:单因素分析显示7个相关预后因素为:卡氏评分(P<0.001)、呼吸困难(P=0.037)、瞻望(P=0.015)、外周血白细胞计数>11×109/L(P=0.012)、淋巴细胞比例<12%(P=0.030)、乳酸脱氢酶>500 U/L(P<0.001)、血清白蛋白<30 g/L(P=0.001)。其中卡式评分<30、乳酸脱氢酶>500 U/L、血清白蛋白<30 g/L、瞻望为4个独立预后因素。结论:本研究揭示了晚期恶性肿瘤患者的生存期预后相关因素,有利于临床更准确地预测患者的生存期,并提供相关治疗。

晚期恶性肿瘤;危险因素;生存期

恶性肿瘤的预后判断在肿瘤治疗领域中非常重要,预后判断准确可以帮助临床医师选择相关的治疗[1]。对于接受姑息治疗的晚期恶性肿瘤患者,生存期的准确预测更是可以有效避免过度治疗及医疗资源的浪费,同时为医务人员及家属进行医疗决策提供科学依据[2]。

研究表明晚期恶性肿瘤的生存期判断,很大程度上取决于患者的一般状态、主要的临床症状和主要的血液学指标[3]。许多国家不仅通过科学的研究,筛选出了具有独立预后因素的指标,并且已建立了用于判断姑息治疗晚期肿瘤患者生存期的方法[4-6],包括姑息预后评分(palliative prognostic score,PaP)[7]、姑息状态指数(palliative performance index,PPI)[8]及癌症预后评分(cancer prognostic score,CPS)[9]等。这些方法虽然在一定程度上提高了临床医师对于患者生存期预测的准确性,但各种方法受其研究人群和所适用患者的生存期长短不一的影响,使用上存在较大限制[10-12]。因而,目前在晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期方面尚未建立统一的标准[13-15]。

本研究旨在分析影响晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期的多种因素,寻找对生存期具有明显影响的因素。同时筛选出具有独立显著意义的预后因素,以更好地指导临床决策。

1 资料和方法

1.1 临床资料

自2007年3月—2012年3月复旦大学附属肿瘤医院姑息治疗科共收治776例晚期恶性肿瘤患者,其中资料完整的271例死亡患者列入本研究。271例患者均为无法耐受手术、放疗和化疗等相关抗肿瘤治疗的晚期恶性肿瘤患者,入院接受最佳支持治疗。

271例死亡患者的平均年龄为63岁(24~93岁)。51.7%(140例)的患者为男性。81.2%的患者获得明确的病理诊断,其他患者均为经治的临床诊断Ⅳ期晚期肿瘤患者。肺癌患者48例(16.4%),乳腺癌患者28例(9.6%),消化系统肿瘤117例(43.2%),妇科肿瘤27例(9.2%),泌尿系统肿瘤18例(6.2%),其他部位肿瘤33例(12.2%)。75.2%的患者明确有远处脏器的转移,其中128例(43.8%)有多于两个部位的远处转移。最常见转移部位为肝脏(102例)和骨(100例)。145例(49.7%)既往接受过手术治疗,108例(37.0%)接受过放疗,160例(54.8%)接受过化疗。

1.2 研究方法

临床资料包括患者的一般信息、主要的临床症状和血液学指标。一般信息及临床症状为入院时采集,血液学指标为入院第2天早上采集。一般信息包括:年龄、性别、诊断、原发恶性肿瘤部位、转移灶数目及部位、既往治疗方式和入院卡氏评分(Karnofsky performance status,KPS);临床症状包括疼痛、恶心呕吐、呼吸困难、咳嗽、纳差、腹胀、便秘、腹泻、失眠、瞻望、出血、恶液质、发热及体重下降。主要的血液学指标包括:外周血白细胞总数(white blood cell,WBC)、血红蛋白(hemoglobin,Hb)、淋巴细胞比例(lymphocyte percentage,Lym%)、中性粒细胞比例(neutrophil percentage,Neu%)、血小板计数(platelet,PLT)、血总胆红素(total bilirubin,TBIL)、碱性磷酸酶(alkaline phosphatase,ALP)、谷丙转氨酶(glutamicpyruvic transaminase,GPT)、谷草转氨酶(glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase,GOT)、乳酸脱氢酶(lactate dehydrogenase,LDH)、白蛋白(albumin,ALB)、血钾、血钠及血钙。生存期定义为入院至死亡的时间(精确到天)。

1.3 统计学处理

数据应用SPSS 16.0统计软件处理,应用Kaplan-Meier法计算生存期,对相关因素进行生存期的单因素分析,采用Log-rank方法检验。通过应用Cox回归模型对单因素分析有意义的因素进行多因素分析,筛选出有独立显著意义的预后因素。建立预后指数方程。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 晚期恶性肿瘤患者总体生存

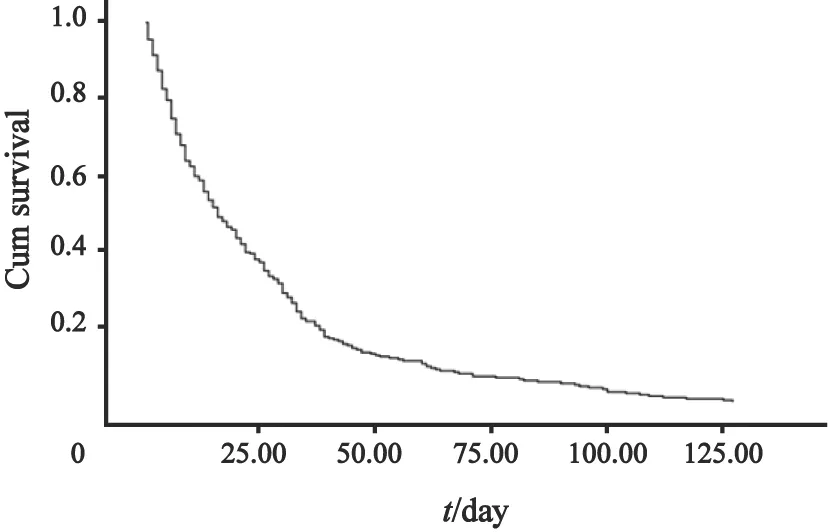

271例死亡患者的平均生存时间为25 d(1~127 d,95%CI:22~28),中位生存时间为16 d(95%CI:13~19)。14例患者在入院1 d内死亡,1周的生存率为70.11%,2周的生存率为52.76%,4周的生存率为32.10%(图1)。

图 1 271例晚期癌症患者总体生存曲线Fig. 1 Total survival curve for 271 advanced cancer patients

2.2 晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期影响因素单因素分析

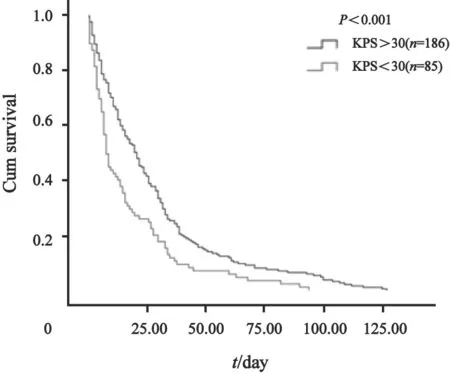

271例患者的中位KPS为30。29.1%的患者KPS<30。本研究中KPS<30组患者同KPS≥30组患者的生存时间差异有统计学意义(P<0.001,图2)。

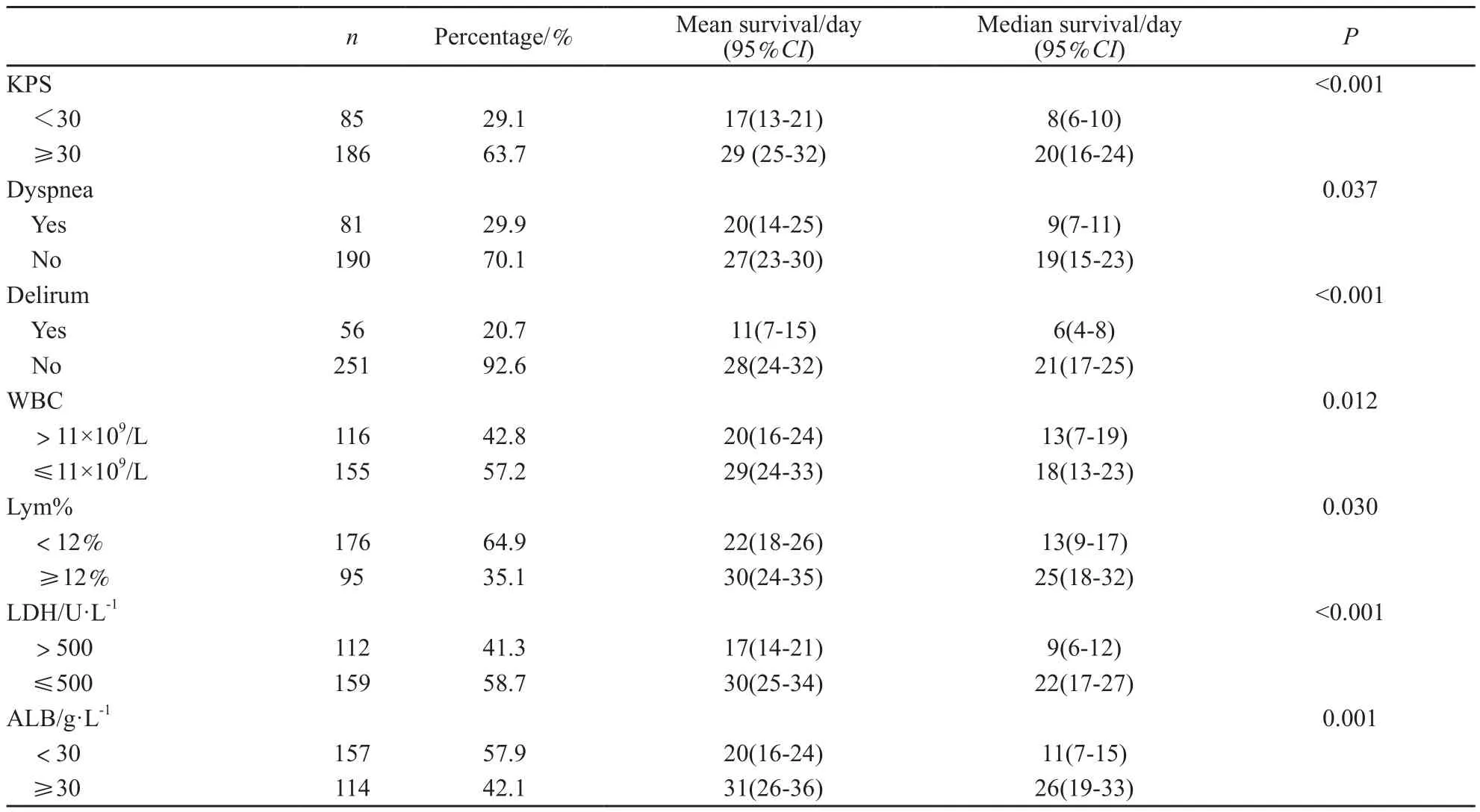

控制晚期肿瘤患者的临床症状是姑息治疗的主要目标,本研究采集了晚期恶性肿瘤患者常见的临床症状。其中,呼吸困难、瞻望与患者的生存期具有明显相关性(P<0.05)。实验室血液学指标比KPS和临床症状具有更好的客观性和可操作性。本研究中,WBC>11×109/L、Lym%<12%、LDH>500 U/L及ALB<30 g/L与生存期有明显的相关性(P<0.05,表1)。

图 2 不同KPS组患者生存曲线Fig. 2 Survival curves for different KPS patients

表 1 晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期影响因素单因素分析Tab. 1 Seven factors related with the survival time according to univariate analysis

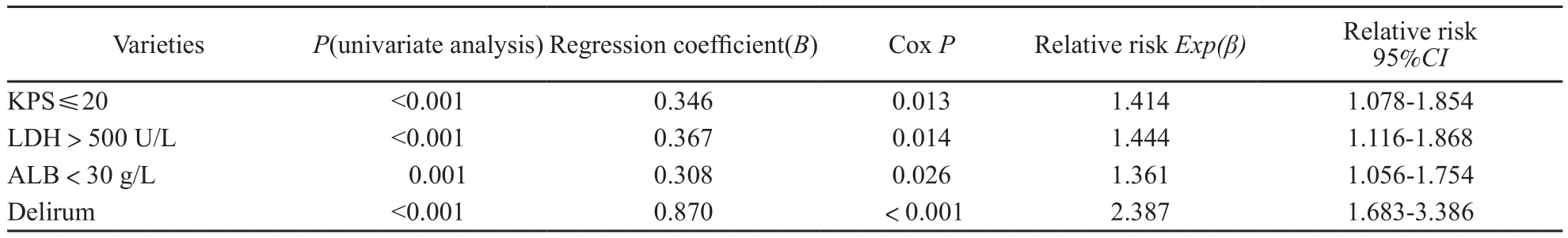

2.3 晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期影响因素多因素分析及Cox回归模型

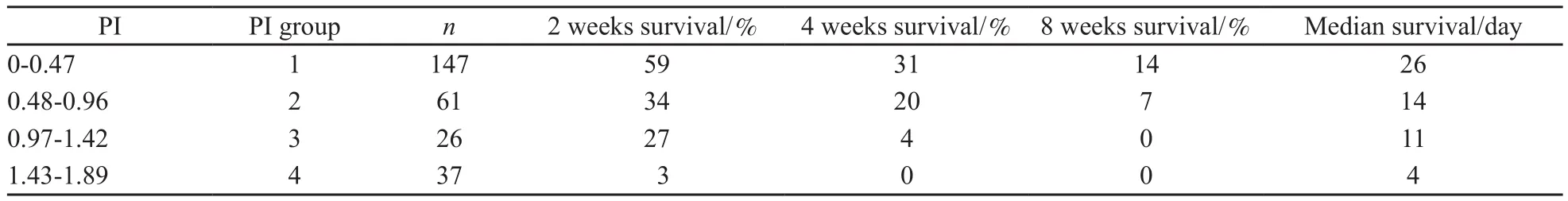

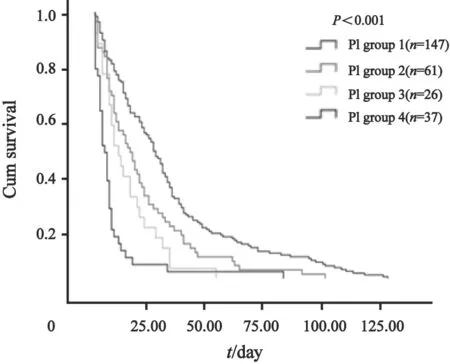

将单因素分析得出的7个因素纳入Cox入选变量,进行Cox回归模型多因素分析,得出KPS<30、瞻望、LDH>500 U/L及ALB<30 g/L为生存期独立影响因素。各因子的相对危险度分别为1.414、1.444、1.364、2.387(表2)。建立最终的生存预后模型为:h(t·x)=h0(t)exp(0.346X1+0.367X2+0.308X3+0.0.870X4),将所有患者的临床因素代入预后指数(PI)方程(是为1,否为0):PI=0.346X1+0.367X2+0.308X3+0.870X4,计算每例患者的PI值,271例数据中PI中位值为0.61(0~1.89)。根据其数值大小分成4个不同的预后组,计算每组相应的中位生存期与生存率(表3),随PI的升高,患者的中位生存期及2、4、8周生存率均呈下降趋势(P<0.001)。不同PI组的生存曲线差异有统计学意义(P<0.001,图3)。

表 2 晚期恶性肿瘤患者生存期影响因素多因素分析Tab. 2 Four independent factors related with the survival time according to multivariate analysis

表 3 不同预后指数组的生存情况Tab. 3 Different survival rate according to different PI group

图 3 不同PI组生存曲线Fig. 3 Survival curves for different PI groups

3 讨 论

本文研究对象为271例接受姑息治疗的晚期恶性肿瘤患者,原发肿瘤部位多样,转移部位、数目和既往病程均不同。研究共得出4个影响患者生存预后的独立因素,与既往该领域研究的一些结果相同,也得出了具有新的值得重视的研究结果。

KPS是临床上评价肿瘤患者一般情况的指标,不仅作为选择治疗方式的参考指标,也是疗效的重要评价标准。对于晚期恶性肿瘤患者,KPS已被多次证实同生存期具有明显相关性[16-17]。值得注意的是KPS评分过程无法排除临床医师的主观印象。而主观印象的获得又同较多临床相关因素有关。然而,这并不影响KPS对于预后判断的价值。

呼吸困难是晚期恶性肿瘤患者常见症状之一,常由多种原因造成[18]。频繁发作且难以控制的呼吸困难也是晚期恶性肿瘤患者最被重视的临床症状,证实与晚期患者的生存预后具有明显的相关性[19]。本研究中,29.9%(81例)的患者主诉呼吸困难,这部分患者的生存期明显短于无该症状的患者。已有研究证实,呼吸困难的出现及程度与Hb降低具有相关性[20]。但本研究并未证实Hb降低为预后因素。两者的相关性及其与生存期的关系值得进一步研究。

瞻望可被认为是晚期癌症患者常见的意识下降综合征[21]。本研究中,20.7%的患者入院时即表现有瞻望症状,与国外报道的26.0%~44.0%相近[22]。目前研究认为,瞻望的出现是临床多因素作用的结果,包括药物、电解质紊乱、内分泌紊乱、低氧血症、感染、副瘤综合征、颅内转移及脱水等[23]。尽管研究报道通过适当的干预,近50%的晚期癌症患者的瞻望是可逆的[24]。但瞻望症状的出现仍是影响晚期癌症患者生存预测的一个重要因素。相关研究根据患者是否有瞻望症状,对已有生存预测模型进行了进一步的优化。瞻望症状的正确评估和临床干预值得进一步探讨。

实验室指标相对临床症状及KPS,具有更好的方便性、客观性及可操作性。WBC>11× 109/L及Lym%<12%均是既往预测模型中的重要组成因素。既往研究认为,WBC升高是独立的预后因素[25]。Ventafridda等[26]报道,在临终15 d内,近40.0%的患者有WBC升高的表现,且WBC升高预示生存期较短,而相对较高的Lym则预示生存期相对乐观。在本研究中,42.8%的患者入院时外周血常规提示WBC计数升高,64.9%的患者Lym%低于12%。WBC升高为预后因素(P=0.012),但多因素分析并不支持其为独立预后因素。Lym%<12%为与生存期相关的独立预后因素。Lym%降低预示机体免疫力下降,而其与厌食(恶液质)、体重下降及C反应蛋白等炎性因子的关系值得进一步的研究。

外周血ALB是评估蛋白功能的简易指标,营养不足及炎性反应均可以抑制白蛋白的合成。通常,正常ALB定义为35~50 g/L。低ALB和Lym%降低都是患者营养不良的表现,而对于生存期<2个月的患者,低ALB起到了更重要的作用[27]。而其作为生存预后因素,已经在多种恶性肿瘤中证实[28]。本研究证实了ALB<30 g/L为独立预后因素。而其与体重下降、水肿和胸腹水的关系值得进一步研究。

高LDH值也已被多次证实为与生存期具有明显相关性的实验室指标,其高表达可能反映了肿瘤的高负荷[29]。Brown等[30]针对乳腺癌骨转移患者生存预后因素的分析提示,LDH>500 U/L的患者其死亡风险为LDH正常患者的6倍。在肺癌、前列腺癌、肠癌及恶性黑色素瘤等多种肿瘤中,LDH值的升高均与患者的不良预后有关[31-33]。

本研究的样本数略显不足,对于建立中国晚期癌症患者生存预测模型尚有一定差距。但已能初步筛选出与生存期相关的诸多因素及相关程度。由于本研究为回顾性研究,某些可能对生存有影响的因素,如心理社会因素、精神因素等并未纳入研究,将在以后的研究中应进行修正。

[1] WEEKS J C, COOK E F, O’DAY S J, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences [J]. JAMA, 2000, 283(2): 203.

[2] MALTONI M, CARACENI A, BRUNELLI C, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: evidence-based clinical recommendations-a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2005, 23(25): 6240-6248.

[3] GLARE P, VIRIK K, JONES M, et al. A systematic review of physicians’ survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients [J]. BMJ, 2003, 327(7408): 195-198.

[4] MORITA T, TSUNODA J, INOUE S, et al. The palliative prognostic index: a scoring system for survival prediction of terminally ill cancer patients [J]. Support Care Cancer, 1999, 7(3): 128-133.

[5] LOPEZ A R , MATEO R M, DEL POZO R R, et al. Validation of a survival prognostic score based on biological parameters in terminal cancer patients assisted by a Home Care Support Team[J]. Medicina Paliativa, 2012, 20(1): 3-9.

[6] GLARE P, VIRIK K. Independent prospective validation of the PaP Score in terminally ill patients referred to a hospitalbased palliative medicine consultation service[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2001, 22(5): 891-898.

[7] GLARE P A, EYCHMUELLER S, MCMAHON P. Diagnostic accuracy of the palliative prognostic score in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer[J].J Clin Oncol, 2004, 22(23): 4823-4828.

[8] STONE C A, TIERNAN E, DOOLEY B A. Prospective validation of the palliative prognostic index in patients with cancer[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2008, 35(6): 617-622.

[9] CHUANG R B, HU W Y, CHIU T Y, et al. Prediction of survival in terminal patients in Taiwan: constructing a prognostic scale[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2004, 28(2): 115-122.

[10] HO F, LAU F, DOWNING M G, et al. A reliability and validity study of the Palliative Performance Scale[J]. BMC Palliat Care, 2008, 7(4): 10.

[11] STIEL S, BERTRAM L, NEUHAUS S, et al. Evaluation and comparison of two prognostic scores and the physicians’estimate of survival in terminally ill patients [J]. Support Care Cancer, 2010, 18(1): 43-49.

[12] OHDE S ,HAYASHI A, TAKAHASI O, et al. A 2-week prognostic prediction model for terminal cancer patients in a palliative care unit at a Japanese general hospital [J]. Palliat Med, 2010, 25(2): 170-176.

[13] GLARE P, SINCLAIR C, DOWNING M, et al. Predicting survival in patients with advanced disease[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2008, 44(8): 1146-1156.

[14] MALTONI M, SCARPI E, PITTURERI C, et al. Prospective comparison of prognostic scores in palliative care cancer populations[J]. Oncologist, 2012, 17(3): 446-454.

[15] SELBY D, CHAKRABORTY A, LILIEN T, et al. Clinician accuracy when estimating survival duration: the role of the patient’s performance status and time-based prognostic categories[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2011, 42(4): 578-588.

[16] CHEUNG W Y, BARMALA N, ZARINEHBAF S, et al. The association of physical and psychological symptom burden with time to death among palliative cancer outpatients[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2009, 37(3): 297-304.

[17] KAO Y H, CHEN C N ,CHIANG J K, et al. Predicting factors in the last week of survival in elderly patients with terminal cancer: a prospective study in southern Taiwan [J]. J Formos Med Assoc, 2009, 108(3): 231-239.

[18] CONILL C, VERGER E, HENRIQUEZ I, et al. Symptom prevalence in the last week of life[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 1997, 14(6): 328-331.

[19] CUERVO PINNA M A, MOTA VARGAS R, REDONDO MORALO M J, et al. Dyspnea-a bad prognosis symptom at the end of life[J]. Am J Hosp Palliat Med, 2009, 26(2): 89-97.

[20] MALTONI M, PIROVANO M, SCARPI E, et al. Prediction of survival of patients terminally ill with cancer. Results of an Italian prospective multicentric study[J]. Cancer, 1995, 75(10): 2613-2622.

[21] SCARPI E, MALTONI M, MICELI R, et al. Survival prediction for terminally ill cancer patients: revision of the palliative prognostic score with incorporation of delirium[J]. Oncologist, 2011, 16(12): 1793-1799.

[22] CENTENO C, SANZ A, BRUERA E. Delirium in advanced cancer patients[J]. Palliat Med, 2004, 18(3): 184-194.

[23] BUSH S H, BRUERA E. The assessment and management of delirium in cancer patients[J]. Oncologist, 2009, 14(10): 1039-1049.

[24] LAWLOR P G, GAGNON B, MANCINI I L, et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective study[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2000, 160(6): 786-794.

[25] TIBALDI C, VASILE E, BERNARDINI I, et al. Baseline elevated leukocyte count in peripheral blood is associated with poor survival in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a prognostic model[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2008, 134(10): 1143-1149

[26] VENTAFRIDDA V, DE CONNO F, SAITA L, et al. Leukocyte-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic indicator of survival in cachectic cancer patients[J]. Ann Oncol, 1991, 2(3): 196.

[27] VIGANO A, BRUERA E, JHANGRI G S, et al. Clinical survival predictors in patients with advanced cancer[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2000, 160(6): 861-868.

[28] GUPTA D , LIS C G. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature[J]. Nutr J, 2010, 9: 69.

[29] HANNAN J L, RADWANY S M, ALBANESE T, et al. Inhospital mortality in patients older than 60 years with very low albumin levels[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2012, 43(3): 631-637.

[30] BROWN J E, COOK R J, LIPTON A, et al. Serum lactate dehydrogenase is prognostic for survival in patients with bone metastases from breast cancer: a retrospective analysis in bisphosphonate-treated patients[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2012, 18(22): 6348-6355.

[31] SMALETZ O, SCHER H I, SMALL E J, et al. Nomogram for overall survival of patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer after castration[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2002, 20(19): 3972-3982.

[32] EGBERTS F, KOTTHOFF E M, GERDES S, et al. Comparative study of YKL-40, S-100B and LDH as monitoring tools for Stage Ⅳ melanoma[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2012, 48(5): 695-702.

[33] CHIBAUDEL B, BONNETAIN F, SHI Q, et al. Alternative end points to evaluate a therapeutic strategy in advanced colorectal cancer: evaluation of progression-free survival, duration of disease control, and time to failure of strategyan Aide et Recherche en Cancerologie Digestive Group Study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(31): 4199-4204.

Factors influencing survival time of advanced cancer patients who

palliative care

GU Xiaoli, CHENG Wen-wu (Department of Palliative Care, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China)

CHENG Wen-wu E-mail: cwwxmm@sina.com

Background and purpose: How to predict the survival length for terminally cancer patients is very important, it will help families and physicians to make decisions. This study aimed to reveal the factors related to the survival time of terminally ill cancer patients who received palliative care in our hospital. Methods: The clinical data of 271 dead patients treated in the Department of Palliative Care, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center from Mar. 2007 to Mar. 2012 were analyzed. The Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test were used to determine the corresponding factors with survival. Cox regression model was used to examine the independent prognostic factors. Different survival length of groups divided by different prognostic indexes was compared by log-rank test. Results: Seven factors were found to be related with the survival according to univariate analysis. The related factors were Karnofsky performance score (P<0.001), dyspnea (P=0.037), delirium (P=0.015), high white blood cell count (P=0.012), low lymphocyte percentage (P=0.030), high lactate dehydrogenase (P<0.001) and low serum albumin (P=0.001). The multivariate analysis selected four independent factors: Karnofsky performance score<30, high lactate dehydrogenase, low serum albumin and delirium.Conclusion: The study shows the clinical survival prognostics with Chinese characteristics. The combination of the seven factors may be useful but more studies in this area deserve further investigated.

Advanced cancer; Risk factors; Survival time

10.3969/j.issn.1007-3969.2013.09.011

R730.5

:A

:1007-3639(2013)09-0759-06

2012-12-28

2013-04-16 )

成文武 E-mail:cwwxmm@sina.com