Disease spectrum and use of cholecystolithotomy in gallstone ileus

2012-06-11

Sydney,Australia

Introduction

The ideal management of acute gallstone ileus is debated.[1-4]Initial definitive biliary surgery is often avoided because of concerns regarding technical difficulty,increased perioperative risk or because it is deemed unnecessary.[1,2]Here we present three cases to highlight some of the pertinent issues,and propose a management scheme to minimize recurrent disease and postoperative complications.

Case reports

Case 1

A 69-year-old man with a background of alcoholic pancreatitis presented with a four-day history of epigastric and right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain,nausea,vomiting and obstipation.On examination,he was febrile with abdominal distension and RUQ tenderness.Blood tests revealed a white cell count of 12.4×109cells/L and lipase of 747 U/L.Liver function test values were elevated with a picture of obstructive jaundice (bilirubin:66 μmol/L; ALP:254 U/L; GGT:732 U/L).Trans-abdominal ultrasound demonstrated two gallstones measuring 20 mm and 30 mm within a thick-walled gallbladder with pericholecystic fluid.Overlying bowel gas made further sonographic interpretation of the biliary tree difficult.A diagnosis of cholecystitis with gallstone pancreatitis and secondary ileus was made and he was initially managed non-operatively.

However,shortly after admission he became increasingly septic with ongoing fever,tachycardia and rigors.Clinical deterioration was investigated with a computed tomography (CT) scan which demonstrated a small bowel obstruction due to a third,30-mm calculus within an ileal loop (Fig.1).There was evidence of extensive pericholecystic in flammation and a probable persistent cholecysto-duodenalfistula.

At laparotomy,the bowel wall surrounding the calculus had become ischemic and a partial small bowel resection was performed with removal of the calculus.The RUQ was not explored.His post-operative course was complicated by a superficial wound infection and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia.He was discharged on day 10 with a plan for elective cholecystectomy in six weeks.

Ten days later,the patient re-presented with a second similar episode.Previously obstructive liver function tests had resolved and an abdominal X-ray showed evidence of small bowel obstruction,pneumobilia and a radio-opaque gallstone in the RUQ (Fig.2).Repeated CT confirmed recurrent gallstone ileus (with a 30-mm calculus in the mid-jejunum) and a single remaining 20-mm gallbladder calculus.The cholecysto-duodenalfistula appeared persistent and there was no evidence of anastomotic breakdown at the site of previous bowel resection.

Fig.1.Coronal CT demonstrating gallstones within small bowel and gallbladder (case 1,arrows identify gallstones).

Fig.2.Plain X-ray showing a classical picture of small bowel obstruction,pneumobilia and opaque gallstone (case 1,second presentation; arrows identify gallstone and pneumobilia).

The patient underwent a second laparotomy,with enterolithotomy and cholecystolithotomy to remove thefinal gallbladder calculus.The thick gallbladder wall was closed primarily without a cholecystostomy drain and thefistula was again left undisturbed.His post-operative course was complicated by pulmonary embolism managed with therapeutic enoxaparin.He was discharged well on day 30.

Case 2

A 71-year-old man with a history of symptomatic cholelithiasis presented with a short history of worsening abdominal discomfort,nausea and profuse vomiting.He was febrile with abdominal distension and a clinically tender RUQ.He had an elevated white cell count of 17×109cells/L and unremarkable liver function test values.An abdominal X-ray demonstrated a calcified density in the RUQ (consistent with either a large gallstone or porcelain gallbladder) and a dilated stomach.Transabdominal ultrasound showed thickening of the gallbladder wall and a large non-mobile calculus within the gallbladder neck.Subsequent CT scanning confirmed gastric outlet obstruction due to a second large calculus in the third part of the duodenum.

At laparotomy,a widefistula from the gallbladder to the second part of the duodenum was found.A large calculus had broken in half (Fig.3),with the proximal part remaining in the gallbladder and the distal part impacted at the D3/4 junction.A subtotal cholecystectomy was performed leaving a small cuff of gallbladder around thefistula tract.A cholangiogram was unable to be performed secondary to in flammatory obliteration of Calot's triangle.The impacted fragment was milked back through the D2fistula tract,which was then closed primarily and reinforced with an omental patch.He had an unremarkable post-operative course and was discharged home on post-operative day 7.

Fig.3.Broken gallstone in case 2.

Fig.4.Duodenotomy and removal of gallstone in case 3.A:CT with duodenal stone; B,C:stone removal; D:an 8-cm gallstone.

Case 3

An 84-year-old woman presented with a twoday history of progressive epigastric abdominal pain and vomiting.Her medical history was significant for mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with good exercise tolerance.Clinically,her abdomen was distended but soft with mild epigastric tenderness.Full blood count,liver function tests and lipase were essentially normal.Ongoing vomiting and a plain X-ray consistent with gastric outlet obstruction prompted a CT scan.This revealed a large calculus within D1 and a closely adherent gallbladder suspicious of a cholecystoduodenalfistula (Fig.4A).

At operation,exploration revealed two separate biliary-entericfistulae; not only between the gallbladder and adjacent D1,but also between the gallbladder and the proximal transverse colon.Bothfistulae were divided and the D1 enterotomy was extended proximally through the pylorus to extract the calculus (Fig.4 B-D).A distal gastrectomy was thus required to resect the extended enterotomy,given inability to close transversely and the risk of enteric leak and/or stenosis following primary closure.Cholecystectomy was completed.Marked in flammatory changes in the region of the colonicfistula necessitated a right hemicolectomy with primary anastomosis,and intestinal continuity was restored with a Billroth II gastrojejunostomy.The patient made a steady recovery and was discharged well on day 17.

Discussion

Gallstone ileus is a rare surgical condition accounting for 1%-4% of all small bowel obstructions.[1,2]However,in patients over the age of 65 it is responsible for up to 25% of small bowel obstructions.[2]It occurs when a large calculus erodes through the gallbladder or bile duct wall typically into the adjacent duodenum,creating a biliary-entericfistula.Stones are most commonly impacted in the terminal ileum (Barnard's syndrome)but also rarely impact in the duodenum causing gastric outlet obstruction (Bouveret's syndrome).[5,6]Bouveret's syndrome is responsible for only 3% of all cases of gallstone ileus.[1]The mortality rate of gallstone ileus has decreased substantially in recent decades but remains significant,with estimates ranging from 11% to 18%.[1,7]

Clinical presentation is typically non-specific,and often with intermittent symptoms of nausea,vomiting,abdominal distension and pain.Only a minority of patients experience biliary symptoms prior to obstruction.Historically,the diagnosis was reliant on the identification of Rigler's triad (dilated small bowel loops,pneumobilia and an aberrant gallstone) on plain X-ray (Fig.2).Whilst these findings are pathognomonic for gallstone ileus,they are present in less than 20% of all cases.[8]The diagnosis is now made more readily by CT.

Until now,management options for gallstone ileus have been divided into two basic approaches.The first,a one-stage procedure,involves a combination of both enterolithotomy to relieve the obstruction and definitive biliary surgery with cholecystectomy andfistula repair.The second option is to perform enterolithotomy only,with or without delayed cholecystectomy.

The one-stage approach eliminates the risk of recurrent gallstone ileus or biliary sepsis.In the presence of residual stones,estimated rates of recurrence range from 5% to 17%[1,9]and over half of these recurrences occur within six months of the index presentation.[1]It would therefore follow that a one-stage procedure is preferable in the presence of known residual stones,either on imaging or because the intestinal stone is faceted,implying the presence of additional stones and thus the risk of recurrence.

Definitive surgery may also eliminate the theoretical risk of patentfistula re flux and resulting biliary malignancy,the precise magnitude of which is difficult to quantify.Retrospective cohort and literature reviews of gallstone ileus report a 2%-6% incidence of biliary malignancy,with the diagnosis frequently only identified incidentally upon histopathological examination.[10,11]Definitive surgery at the index presentation may reduce this long-term risk with a total or subtotal cholecystectomy combined with excision and primary closure of thefistula where possible.

However,as case 3 demonstrates,this approach is potentially technically demanding in the presence of extensive sub-hepatic in flammation and the surgeon must be prepared for a resection if thefistula cannot be repaired primarily.Furthermore,there is evidence to suggest that performing definitive biliary surgery increases morbidity and mortality rates when compared with enterolithotomy alone.[1,2,7]A review by Reisner and Cohen of 1001 gallstone ileus cases reported a 16.9%mortality rate for patients undergoing definitive surgery as compared with 11.7% when enterolithotomy was performed in isolation.[1]Doko et al[7]also found urgentfistula repair to be the only significant predictor of postoperative complications in their case series.Suchfigures have been reinforced by similar findings reported more recently in a review by Ravikumar and Williams.[2]They go on to suggest that enterolithotomy alone may reduce the morbidity of combined biliary surgery and definitive,one-stage intervention should only be considered in lowrisk patients.[2]

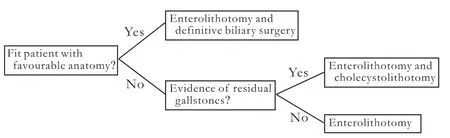

In keeping with this,we only advocate the onestage approach in relativelyfit patients with known residual stones and favorable anatomy.Severe sepsis with hemodynamic and/or end organ compromise,significant pre-existing comorbidity,extensive previous upper abdominal surgery,or excessive radiological pericholecystic in flammation are examples of our contraindications to definitive biliary surgery (case 1).

Clearly,a technique that reduces the risk of gallstone ileus recurrence without the risk of definitive biliary surgery would be ideal in this circumstance.While cholecystolithotomy has previously been promoted as a technique useful for management of gallstone disease in patients at too high risk for surgery,or in whom preservation of an intact functioning gallbladder is desirable,[12]it has not previously been reported as a management option for gallstone ileus.This involves open cholecystotomy with removal of stone(s) and primary closure of the thickened gallbladder wall at the time of enterolithotomy.Whilst rates of gallstone recurrence following cholecystolithotomy approach 40% at ten years,[12]this approach significantly reduces the risk of recurrent gallstone ileus without exposing the patient to the increased morbidity of formal resection andfistula closure.Had this approach been taken initially in case 1 for example,an unplanned readmission with return to theatre and a further month in hospital may have been avoided.Fig.5 illustrates an algorithm we propose for the initial approach to Barnard's syndrome.

Fig.5.Proposed flowchart for initial management of Barnard's syndrome.

Cholecystotomy and primary closure may be combined with placement of a cholecystostomy drain to maintain gallbladder decompression.While we have not found this to be routinely necessary,decompression may assist in closure of a patentfistula.Cholecystography is performed via the drain at six weeks to ensure adequate biliary drainage prior to removal.This study also provides valuable anatomical information about the biliary tree and potentialfistula persistence,which aids in planning of any future definitive surgery.

Cases of Bouveret's syndrome can create diagnostic doubt and are technically challenging owing to duodenal inaccessibility.The diagnostic role of endoscopy has been advocated[6,13]and some consider this the"mainstay" of diagnosis.[13]However,a review of 128 cases by Cappell and Davis reported that the diagnosis was identified endoscopically in <70% of cases.[6]In addition,endoscopic stone retrieval was successful in only 10% of cases and is not useful in management of the existing biliary-entericfistula or associated sepsis.

Despite this,more recent studies highlight the utility of endoscopic intervention in selected cases,citing the low morbidity and mortality associated with such an approach.[14]A range of endoscopic approaches beyond simple stone retrieval are now possible.Mechanical,electrohydraulic and laser lithotripsy in addition to argon plasma coagulation are all forms of non-operative endoscopic treatment that may be employed where local resources and expertise allow.Fancellu et al[14]argue that such non-operative approaches are gaining importance given the ability of high-risk patients to tolerate endoscopic intervention with low morbidity and"insignificant mortality".

Irrespective of advancements in non-operative management,>90% of Bouveret's cases still require urgent surgery.[13]Retrieval of a stone that can be manipulated at operation may require gastrotomy or duodenotomy[6]and is often combined with definitive resection of thefistula tract and gallbladder.Case 3 is an example of an unexpectedly complexfistula that required multivisceral resection and reinforces the need for caution when approaching such pathology.Elderly,compromised patients do not tolerate such aggressive intervention.Thus,the initial dissection and definition of anatomical structures must be cautious so as to avoid potentially irreversible "point of no return" steps in favor of more conservative solutions to duodenal obstruction.It may be preferable to avoid the RUQ completely if possible,milking a mobile stone into a more favorable position for enterolithotomy.As previously discussed,management of the biliary tree may then follow.

If the gallbladder is preserved at initial operation,the issue of delayed cholecystectomy must be addressed.In the absence of retained stones,biliary obstruction and sepsis,the biliary-entericfistula is reported to close spontaneously in a high proportion of cases.[1]However,5% of the patients who have undergone an enterolithotomy alone go on to develop biliary symptoms and 10% require an unplanned reoperation.[1]A recent review of over 200 cholecystocolonicfistulas also reported a 2% risk of biliary malignancy,[11]reinforcing the ever-present,albeit low risk of malignant transformation.Thus,we advocate offering delayed cholecystectomy,with a planned laparoscopic approach,to all relativelyfit patients in whom the predicted peri-operative morbidity is low.Given the potential for complex biliary surgery in this setting,patients should be managed in dedicated hepato-biliary surgical units.

In conclusion,gallstone ileus is a highly morbid condition and residual stones should not be left in situ given the potential for recurrence.Following enterolithotomy,definitive one-stage surgery in typically compromised elderly patients must be weighed against the risk of recurrence.We suggest a safer and simpler approach involving open cholecystolithotomy for the removal of residual gallstones when the patient is not suitable for definitive biliary surgery.Acute or interval definitive biliary surgery should be undertaken in specialized hepato-biliary units.

Contributors:All authors drafted the manuscript.WNE,RS,and SJS were involved in the clinical care of patients.WNE,GJS,and RS collected clinical data.All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.SJS is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Reisner RM,Cohen JR.Gallstone ileus:a review of 1001 reported cases.Am Surg 1994;60:441-446.

2 Ravikumar R,Williams JG.The operative management of gallstone ileus.Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279-281.

3 Hussain Z,Ahmed MS,Alexander DJ,Miller GV,Chintapatla S.Recurrent recurrent gallstone ileus.Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:W4-6.

4 Webb LH,Ott MM,Gunter OL.Once bitten,twice incised:recurrent gallstone ileus.Am J Surg 2010;200:e72-74.

5 Bouveret L.Stenose du pylore adherent a la vesicule.Rev Med(Paris) 1896;16:1-16.

6 Cappell MS,Davis M.Characterization of Bouveret's syndrome:a comprehensive review of 128 cases.Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2139-2146.

7 Doko M,Zovak M,Kopljar M,Glavan E,Ljubicic N,Hochstädter H.Comparison of surgical treatments of gallstone ileus:preliminary report.World J Surg 2003;27:400-404.

8 Lassandro F,Gagliardi N,Scuderi M,Pinto A,Gatta G,Mazzeo R.Gallstone ileus analysis of radiological findings in 27 patients.Eur J Radiol 2004;50:23-29.

9 Clavien PA,Richon J,Burgan S,Rohner A.Gallstone ileus.Br J Surg 1990;77:737-742.

10 Day EA,Marks C.Gallstone ileus.Review of the literature and presentation of thirty-four new cases.Am J Surg 1975;129:552-558.

11 Costi R,Randone B,Violi V,Scatton O,Sarli L,Soubrane O,et al.Cholecystocolonicfistula:facts and myths.A review ofthe 231 published cases.J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009;16:8-18.

12 Zou YP,Du JD,Li WM,Xiao YQ,Xu HB,Zheng F,et al.Gallstone recurrence after successful percutaneous cholecystolithotomy:a 10-year follow-up of 439 cases.Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2007;6:199-203.

13 Lowe AS,Stephenson S,Kay CL,May J.Duodenal obstruction by gallstones (Bouveret's syndrome):a review of the literature.Endoscopy 2005;37:82-87.

14 Fancellu A,Niolu P,Scanu AM,Feo CF,Ginesu GC,Barmina ML.A rare variant of gallstone ileus:Bouveret's syndrome.J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:753-755.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking gallbladder cancer and causing obstructive cholestasis

- Liver transplantation in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type I disease

- High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation as a bridging therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients awaiting liver transplantation

- Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy:spleen-preservation does not increase morbidity

- Expression of HBx protein in hepatitis B virusinfected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- Effect of endogenous hypergastrinemia on gallbladder volume and ejection fraction in patients with autoimmune gastritis