Efficacy and factors in fluencing treatment with peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C

2012-06-11

Harbin,China

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is a serious global health concern.In China,hepatitis C virus(HCV) infection is characterized by an increasing prevalence during ageing.The burden of CHC in elderly persons is expected to increase significantly during the next 2 decades.Most of the older adults with chronic HCV infection acquire the disease earlier in life and have a significantly longer duration of infection than younger patients.In cohort studies of patients with chronic HCV infection,the rate offibrosis and cirrhosis development is higher among those infected at an older age.[1]Preexisting chronic disease such as hypertension,coronary artery disease,and diabetes may contribute to the increase of side effects associated with ageing in HCV-infected patients treated with antiviral drugs.[2]The rate of interferon(IFN) α discontinuation or dose reductions due to a higher incidence of side effects in elderly patients is high.The incidence of hemolytic anemia due to ribavirin increases with age[3]and dose reduction or ribavirin discontinuation have been reported to be more frequent in patients of 55 years or older.[4]Older patients have poorer adherence to the standard-of-care regimen.Thus,treating older patients with a ribavirin-based antiviral therapy may be more difficult.Despite higher rates of side effects,dose modification,and discontinuation of treatment,adherence to the therapy is crucial to achieve a virologic response in older patients.Current guidelines recommend the use of response-guided therapy to predict sustained virologic response (SVR) rates in patients with different HCV genotypes,and the independent factor associated with SVR is the presence of rapid virologic response (RVR).The role of RVR in predicting SVR in elderly patients has not been fully clarified.The value of RVR in predicting SVR is worth studying.

Data from meta-analysis and large,randomized,clinical trials of combination therapy with IFN-α or peginterferon alpha plus ribavirin have shown that age older than 40 years is an independent predictor of reduced SVR.[5,6]Clinical trials generally exclude patients >65 years of age,and data on the efficacy of treatment with peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin among older patients are scarce.A tendency toward a lower SVR rate was observed among older patients who received combination therapy with conventional IFN plus ribavirin in some studies.[7]Nevertheless,only a few studies with limited case numbers,most of which were retrospective,reported the efficacy and safety of peginterferon and ribavirin in older patients with CHC.[8]Honda et al[9]found that the SVR rate was lower in elderly patients than in younger patients,and that in elderly patients combination therapy was most beneficial for genotype 1 patients,male patients with HCV RNA concentrations <2×106IU/mL,and patients with genotype 2.However,the efficacy and tolerability of peginterferon and ribavirin combination therapy in elderly patients according to gender have not been fully elucidated.

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of 417 CHC patients treated with peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin,evaluated the efficacy of combination therapy in elderly patients,and studied the factors related to SVR.

Methods

Study population and study design

CHC patients were diagnosed by HCV-positive serum antibodies and detectable serum HCV RNA and compensated liver disease.Patients were excluded if they had hepatitis A,B,D,E or HIV infection.Further exclusion criteria included autoimmune disease,psychiatric disease,uncontrolled diabetes mellitus,symptomatic cardiac or cardiovascular diseases,alcohol intake >20 g daily and drug abuse.Patients were ineligible if they had received IFN and/or ribavirin previously.Neutrophil count had to be at least 1.5×109/L,platelet count >100×109/L,hemoglobin level >120 g/L in women and 130 g/L in men,and serum creatinine level <1.5 times the upper limit of normal.Decompensated liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in all patients were excluded by CT and/or MRI and/or elevated alpha-fetoprotein.

Five hundred andfifty-seven consecutive patients were treated with peginterferon and ribavirin at the Department of Infectious Diseases in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University between 2004 and 2009.One hundred and forty patients could not be evaluated because of incomplete data.Four hundred and seventeen who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled in this study.These patients were divided into two groups according to age:patients aged ≥65 years (n=140) and patients aged <65 years (n=277).The study was approved by the Ethics Committee according to the Declaration of Helsinki.All patients gave written informed consent before treatment.

Treatment regimen and dose modifications

Dosage reduction of peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin was advised for managing neutropenia,thrombocytopenia and anemia.The peginterferon dose was modified by a 45 μg stepwise decrease to enhance adherence.When the patient's absolute neutrophil count fell below 0.75×109/L,the dose of peginterferon alpha-2a was reduced to 135 or 90 μg per week; when the count fell below 0.5×109/L,peginterferon alpha-2a was discontinued temporarily.When the patient's platelet count fell below 50×109/L,the dose of peginterferon alpha-2a was reduced to 90 μg per week; when the count fell below 25×109/L,peginterferon alpha-2a was discontinued temporarily.The dose of ribavirin was reduced by 200 mg/day when the patient's hemoglobin concentration fell below 100 g/L.[10]Ribavirin was discontinued when the patient's hemoglobin concentration fell below 85 g/L.Patients received peginterferon alpha-2a alone if ribavirin was stopped.Restoration of the treatment was permitted if laboratory abnormality improved.The use of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor was permitted to manage adverse hematologic events.

Serum HCV RNA and HCV genotyping

Serum antibodies to HCV were detected by a third-generation HCV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay(Ortho Diagnostic Systems,Raritan,NJ).Serum HCV RNA level was measured by a quantitative RT-PCR assay(Cobas Amplicor HCV Monitor 2.0; Roche Diagnostic Systems,Branchburg,NJ) at baseline and weeks 4,12,and every 12 weeks thereafter during treatment,at the end of treatment,and at 24 weeks of follow-up.The lower detection limit of the qualitative assay was 100 copies/mL.The HCV genotype was determined by restriction fragment length polymorphism of sequences amplified in the 5' non-coding region.

Liver histology

Pretreatment liver biopsy specimens were analyzed forfibrosis on a scale of F0-F4 (F0,nofibrosis; F1,portalfibrosis without septa; F2,portalfibrosis with few septa;F3,numerous septa without cirrhosis; and F4,cirrhosis),and for necroin flammatory activity on a scale of A0-A3(A0,no histological activity; A1,mild; A2,moderate;and A3,severe activity).Liver biopsy was performed in 70 patients (50.0%) aged ≥65 years and 125 (45.1%) aged<65 years.The other patients refused biopsy.

Observation indicators

Achievement of RVR,complete early virologic response (cEVR),partial early virologic response (pEVR),end-of-treatment virologic response (ETVR) and SVR of patients were recorded.RVR was defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA after 4 weeks of combination therapy.cEVR was defined as HCV RNA-negative at week 12,but no RVR.pEVR was defined as ≥2 log10drop in HCV RNA level from baseline at week 12,but no RVR or cEVR.Patients with undetectable virus at the end of treatment were considered to have achieved an ETVR.Relapse was defined as patients with undetectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment and detectable HCV RNA during follow-up.Only patients with undetectable virus at the end of treatment and again 24 weeks after completion of treatment were considered to have achieved a SVR.

The categories and severity of adverse events were registered.Reduction of drug was defined as reduction of peginterferon alpha-2a or ribavirin over 20% of the scheduled dosage and recorded.The rate of peginterferon alpha-2a reduction,the rate of ribavirin reduction or discontinuation,the cumulative exposure of peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin and virologic response rates (RVR,cEVR,pEVR,ETVR,SVR and relapse rate) of the two groups were compared.The effect of gender and HCV load on SVR was studied.

Statistical analysis

The clinical,biochemical and virologic characteristics of the patients were expressed as mean±SD.Student's t test was used when necessary for statistical comparison of quantitative data,whereas the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used when necessary for qualitative data.In all analyses,a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors related to SVR.In the multivariate logistic regression model,efficacy of combination antiviral therapy (coded as 1,SVR; or 0,without SVR)was defined as the dependent variable,and several factors (age,sex,HCV RNA level,ALT level,genotype,body weight,body mass index,hemoglobin level,white blood cell count,platelet count,histological activity,histologicalfibrosis,peginterferon alpha-2a reduction,ribavirin reduction or discontinuation and RVR) were defined as independent variables.Variables that achieved statistical significance in univariate analysis (P<0.05)were subsequently included in logistic regression analysis.Selection of variables was based on a stepwise regression analysis using the forward selection method.All analyses were performed using a statistical software package (SPSS,version 10.0; Chicago,IL,USA).

Results

Characteristics of patients at baseline

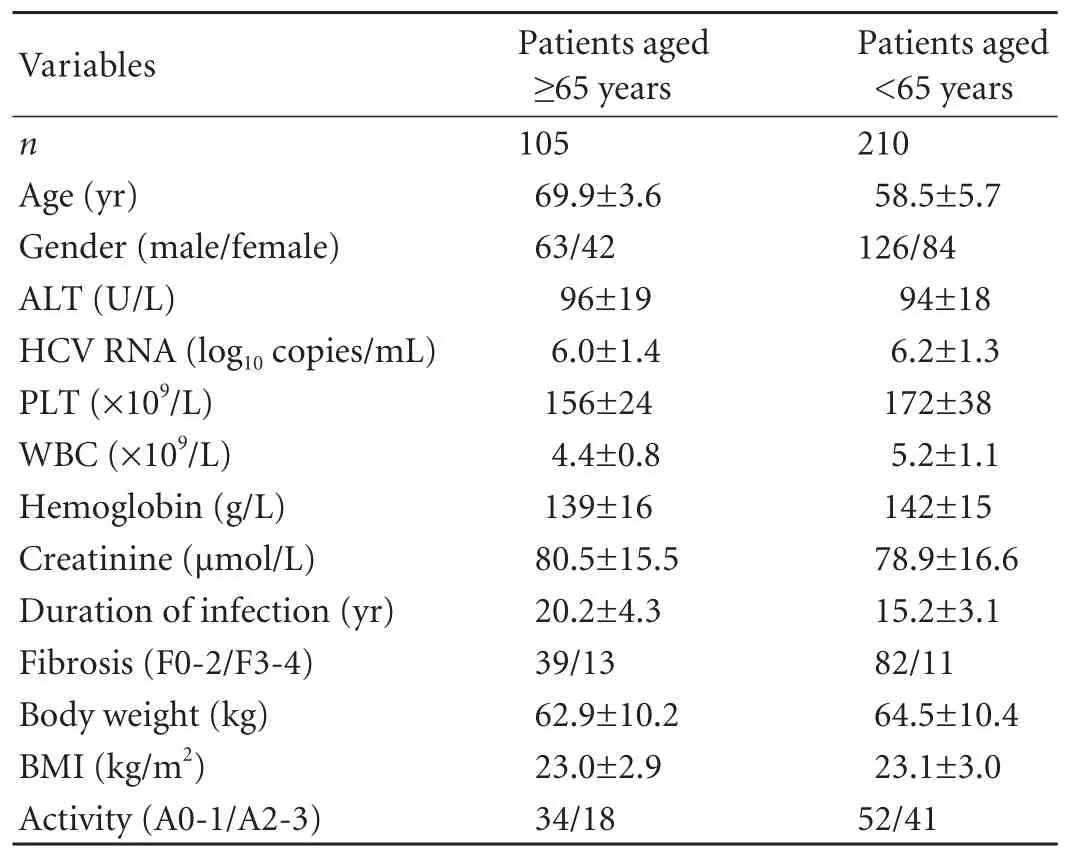

Patients aged ≥65 years had significantly lower mean white blood cell counts and mean platelet counts than those aged <65.Patients aged ≥65 had a longer duration of HCV infection than those aged <65.Liverfibrosis was more advanced in patients aged ≥65 than in those aged <65.No significant difference was found between patients aged ≥65 and those aged <65 in gender,distribution of HCV genotype,HCV RNA concentration and serum ALT level (Tables 1 and 2).

Side effects and dose modifications

There was no serious adverse event during the treatment with peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin.Side effects and dose modifications of the two groups are presented in Table 3.Patients aged ≥65 had a higher incidence of side effects than those aged <65 (72.1%,101/140 vs 48.4%,134/277; χ2=21.358,P<0.001).

Comparison of the rate of drug dose modifications

The rate of peginterferon alpha-2a reduction was 30.0% (42/140) in patients aged ≥65 and 26.7% (74/277)in those aged <65,showing no significant difference(χ2=0.500,P=0.480).Similar results were seen in patients with genotype 1 (31.4%,33/105 vs 23.8%,50/210; χ2=2.094,P=0.148) and with genotype 2 (25.7%,9/35 vs 35.8%,24/67; χ2=1.073,P=0.300).

Ribavirin reduction or discontinuation was more frequent in patients aged ≥65 than in those aged <65(37.1%,52/140 vs 20.2%,56/277; χ2=13.883,P<0.001).Similar results were seen in patients with genotype 1(41.0%,43/105 vs 22.9%,48/210; χ2=11.157,P=0.001).For genotype 2,there was no significant difference in the rate of ribavirin reduction or discontinuation between the two groups (25.7%,9/35 vs 11.9%,8/67; χ2=3.040,P=0.076).

Cumulative exposure of peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin

For genotype 1,the average cumulative exposure of peginterferon alpha-2a was 8180±400 μg in patients aged ≥65 and 8250±450 μg in those aged <65,showing no significant difference (t=1.403,P>0.05); the average cumulative exposure of ribavirin was lower in patientsaged ≥65 than those aged <65 (283±30 g vs 315±25 g;t=9.417,P<0.01).

Table 1.Characteristics of 315 CHC genotype 1 patients at baseline

For genotype 2,the average cumulative exposure of peginterferon alpha-2a was 3949±250 μg in patients aged ≥65 and 4001±200 μg in those aged <65,showing no significant difference (t=1.065,P>0.05); the average cumulative exposure of ribavirin was 151±30 g in patients aged ≥65 and 161±31 g in those aged <65,showing no significant difference (t=1.482,P>0.05).

Mean value of serum HCV RNA after treatment

For genotype 1,the mean serum HCV RNA level of patients aged ≥65 at weeks 4,12,24,36,48,and 72 after treatment was 4.5±1.0,3.2±0.5,2.4±0.6,2.3±0.5,2.2±0.4,and 3.2±0.7 log10copies/mL,and the mean change in log10copies/mL from baseline was -1.5,-2.8,-3.6,-3.7,-3.8,and -2.8,respectively.The mean serum HCV RNA level of patients aged <65 at weeks 4,12,24,36,48,and 72 after treatment was 4.2±0.9,2.8±0.5,2.4±0.5,2.2±0.4,2.1±0.4,and 2.8±0.6 log10copies/mL,and the mean change from baseline was -2.0,-3.4,-3.8,-4.0,-4.1,and -3.4,respectively.

Table 2.Characteristics of 102 CHC genotype 2 patients at baseline

Table 3.Comparison of side effects and dose modifications of two groups

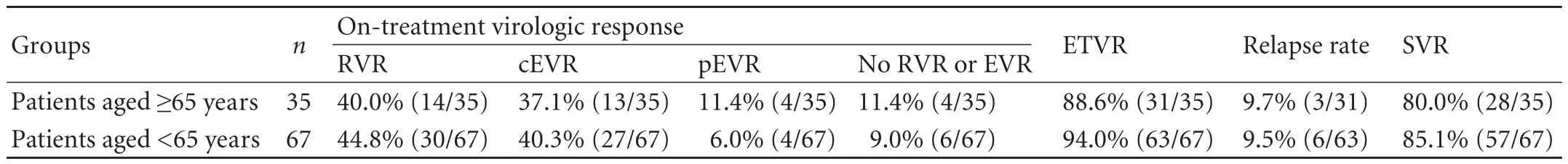

Table 4.Comparison of virologic response rates between two groups for genotype 2

For genotype 2,the mean serum HCV RNA level of patients aged ≥65 at weeks 4,12,24,and 48 after treatment was 3.5±0.8,2.5±0.6,2.2±0.2,and 2.4±0.6 log10copies/mL,and the mean change in log10copies/mL from baseline was -2.4,-3.4,-3.7,and -3.5,respectively.The mean serum HCV RNA level of patients aged <65 at weeks 4,12,24,and 48 after treatment was 3.4±0.7,2.4±0.6,2.1±0.4,and 2.3±0.5 log10copies/mL,and the mean change from baseline was -2.7,-3.7,-4.0,and -3.8,respectively.

Virologic response rates

There was a significant difference in on-treatment virologic response between the two groups for genotype 1 (χ2=14.812,P=0.002).For genotype 1,patients aged≥65 had a lower cEVR rate than those aged <65 (30.5%,32/105 vs 48.1%,101/210; χ2=8.908,P=0.003); patients aged ≥65 had a higher pEVR rate than those aged <65(33.3%,35/105 vs 16.7%,35/210; χ2=11.250,P=0.001).The ETVR rate of patients aged ≥65 was 80.0% (84/105)and 84.8% (178/210) in patients aged <65; patients aged≥65 had a lower SVR rate than those aged <65 (40.0%,42/105 vs 60.0%,126/210; χ2=11.250,P=0.001); patients aged ≥65 had a higher relapse rate than those aged <65(50.0%,42/84 vs 29.2%,52/178; χ2=10.718,P=0.001).

There were no significant differences in virologic response rates (RVR,cEVR,pEVR,ETVR,SVR and relapse rate) between the two groups in patients with genotype 2 (Table 4).

Effect of gender on SVR

For genotype 1,in patients aged ≥65,the SVR rate of females was lower than that of males (28.6%,12/42 vs 47.6%,30/63; χ2=8.150,P=0.004); in patients aged <65,the SVR rate was 65.5% (55/84) in females and 56.3%(71/126) in males,showing no significant difference(χ2=1.749,P=0.186).For genotype 2,in patients aged ≥65,the SVR rate was 85.7% (12/14) in females and 76.2%(16/21) in males,showing no significant difference(χ2=0.476,P=0.490); in patients aged <65,the SVR ratewas 88.9% (24/27) in females and 82.5% (33/40) in males,showing no significant difference (χ2=0.518,P=0.472).

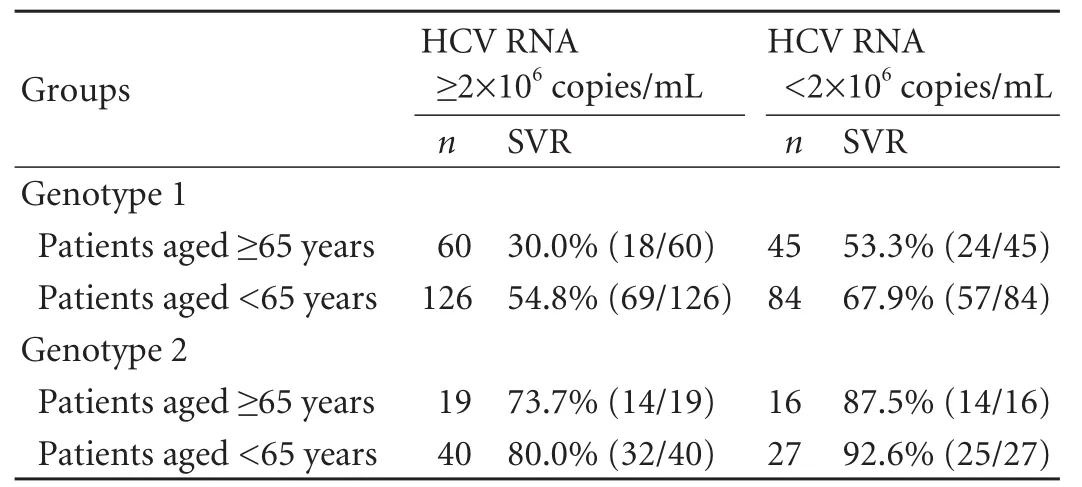

Table 5.Effect of HCV load on SVR

Effect of baseline viral load on SVR

For genotype 1,in the high viral load group,patients aged ≥65 had a lower SVR rate than those aged <65(χ2=10.010,P=0.002); in the low viral load group,there was no significant difference in SVR rate between patients aged ≥65 and those aged <65.For genotype 2,there were no significant differences in SVR rate between patients aged ≥65 and those aged <65 regardless of viral load (Table 5).

Role of RVR in predicting SVR

The relationship between the decline of the levels of serum HCV RNA and SVR was assessed at week 4(achieving RVR).For all patients,the SVR rates of those who had achieved RVR (82.7%,86/104) were significantly higher than those who had not (53.4%,167/313;χ2=28.158,P<0.001).Similar results were seen in patients aged ≥65 (81.3%,26/32 vs without RVR 40.7%,44/108;χ2=16.204,P<0.001) and those aged <65 (83.3%,60/72 vs without RVR 60.0%,123/205; χ2=12.940,P<0.001).

Predictive factors associated with SVR of CHC patients

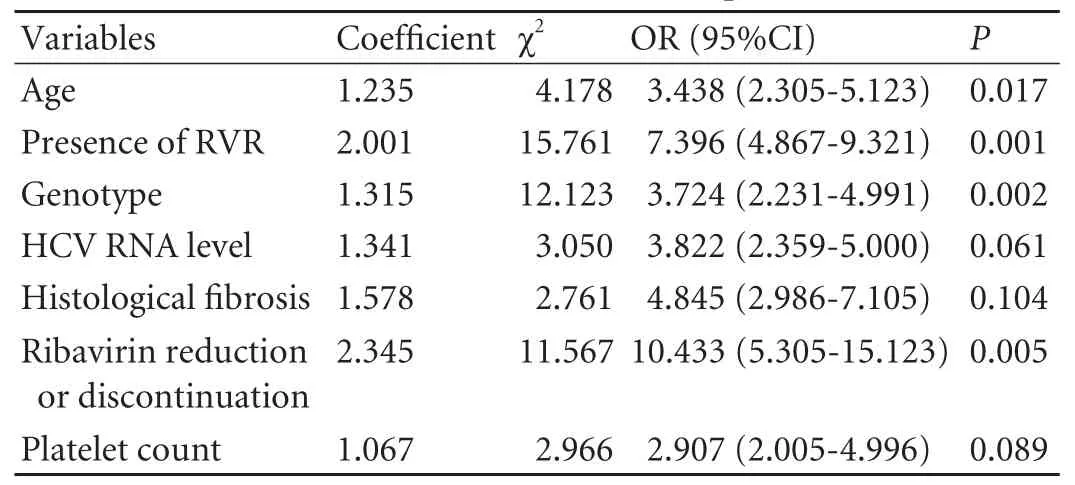

In univariate analysis,age,HCV RNA level,genotype,platelet count,histologicalfibrosis,ribavirin reduction or discontinuation and presence of RVR were associated with SVR (Table 6).Whereas in multivariate logistic regression analysis,the independent factors associated with SVR were age,genotype,ribavirin reduction or discontinuation and presence of RVR (Table 7).

Predictive factors associated with SVR of patients aged ≥65 years

Table 6.Univariate analysis of association between SVR and in fluential factors in CHC patients

Table 7.Multivariate logistic regression analysis of association between SVR and in fluential factors in CHC patients

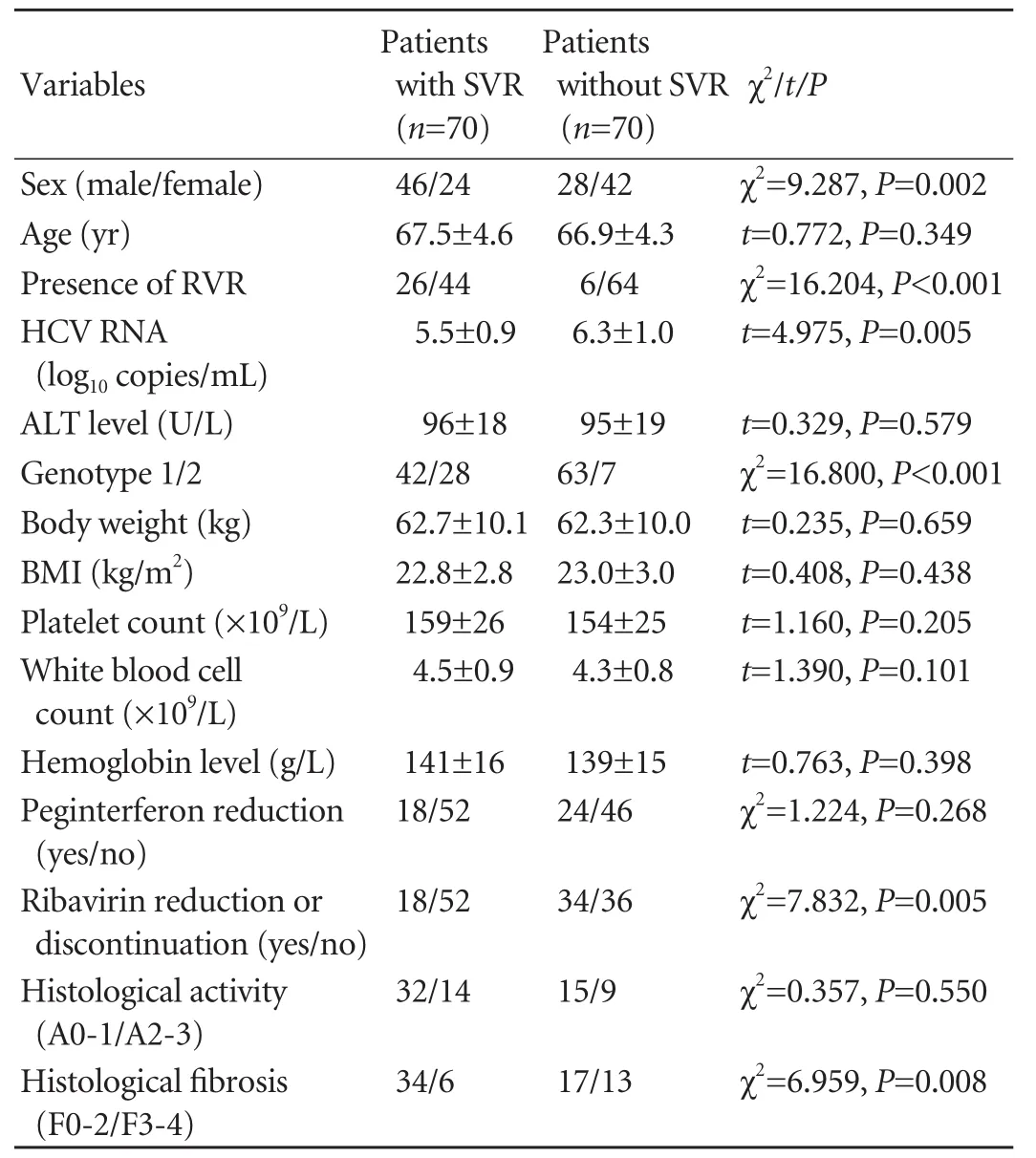

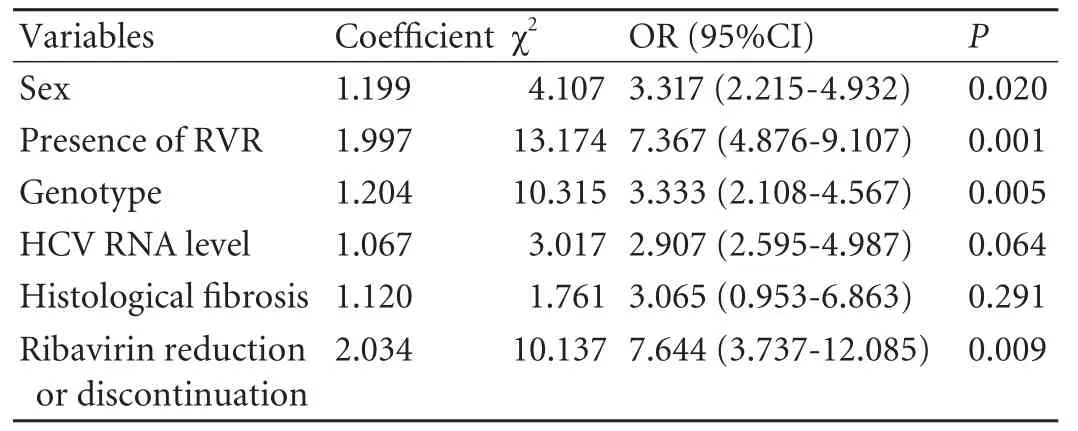

To identify elderly patients who may particularly benefit from combination therapy,we determined the factors associated with SVR.In univariate analysis,sex,HCV RNA level,genotype,histologicalfibrosis,ribavirin reduction or discontinuation and presence of RVR were associated with SVR (Table 8).Whereas in multivariate logistic regression analysis,the independent factors associated with SVR of patients aged ≥65 years were sex,genotype,ribavirin reduction or discontinuation and presence of RVR (Table 9).

Table 8.Univariate analysis of association between SVR and in fluential factors in patients aged ≥65 years

Table 9.Multivariate logistic regression analysis of association between SVR and in fluential factors in patients aged ≥65 years

Discussion

A combination of IFN or peginterferon plus ribavirin is the recommended form of therapy for patients with CHC.Older patients may have negative prognostic factors such as advancedfibrosis or cirrhosis resulting from the longer duration of the disease.[11]Older patients have decreased cardiovascular and pulmonary function and are thus less resistant to the anemia induced by ribavirin.Moreover,impaired renal function results in increased blood levels of ribavirin,which may also lead to more frequent adverse events.[12]In addition,higher levels of drug intolerance,particularly to ribavirin,have been reported in older patients,resulting in reduced adherence to therapy.[8]This leads to reduced drug exposure and,consequently,lower rates of SVR.[13]Because randomized controlled trials generally exclude patients aged 65 years and older,few data are available concerning the efficacy and tolerance of this treatment in older patients.Several reports on the efficacy and safety of peginterferon combined with ribavirin for the treatment of older CHC patients suggest that more frequent dose modifications of ribavirin in those >50 years likely contribute to the observed higher relapse rates and lower SVR rates.[14,15]Different virus- and host-related baseline parameters are known to predict the probability of SVR including HCV genotype,HCV viral load,age,gender and liverfibrosis.But response to treatment in patients with CHC,with reference to age and gender,has not been examined fully.To address this question,we retrospectively evaluated the effect of age and gender on the treatment of CHC.

We found that patients aged ≥65 years had significantly lower mean white blood cell counts and mean platelet counts than patients aged <65 and thefibrosis stage was more advanced in patients aged ≥65 than in patients aged <65.The high incidence of side effects in patients aged ≥65 could be partly responsible for this.There were hematologic adverse events(neutropenia,thrombocytopenia and anemia),but no serious adverse events in our study.So combination treatment with peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin may be safely extended to elderly patients with no major contraindications.Caution should be taken when treating older patients because of higher rates of side effects.

Honda et al[16]examined CHC patients with similar backgrounds,except for age,and found that combination therapy was comparably effective in patients aged ≥60 and those aged <60,although the ribavirin discontinuation rate was higher among older patients.The results suggest that the in fluence of age on the virological response may be due to the higher reduction rate,not the age itself.We found that patients aged ≥65 with genotype 1 had a higher relapse rate and a lower SVR rate than those aged <65.The higher rate of ribavirin discontinuation or reductions and lower cumulative drug exposure to ribavirin due to a higher incidence of hemolytic anemia in elderly patients may first explain the higher relapse rate and lower SVR rate.Increasing rates of bridgingfibrosis with age may also play a role in reducing the sustained response to combination therapy.Several reports describe a gradual decline in the ability of the immune system to protect the host from pathogens and tumors with aging.The agerelated immune dysfunction may result from a decrease in the number and function of naive T cells.[17]It is worth studying whether age-specific differences in the immune response lead to different rates of response to treatment in different age groups.

We found that compared with patients aged <65 years,the pEVR and relapse rate of those aged ≥65 with HCV genotype 1 were high.For HCV genotype 1 elderly patients with pEVR,48-week combination treatment was not enough to clear HCV.The patients with pEVR might benefit from prolongation of therapy from 48 to 72 weeks.This benefit could derive from a lower relapse rate after the extension of the plasma HCV RNA-free period in slower responders.In a previous retrospective study of older patients,treatment inferiority in elderly patients was observed only among those infected with HCV-1 and not among those infected with HCV-2/3.[8]Our study showed that age had no impact on the rates of virological responses for patients with genotype 2.All patients with genotype 2 should be considered for treatment regardless of age.

In the older population,the gender associated with an SVR changes from male to female.The in fluence of gender and age on treatment with peginterferon and ribavirin was evaluated in this study.We found no difference in SVR rate between females and males aged <65,but in patients ≥65 years old,the SVR rate of females was significantly lower than that of males.Our results are consistent with Sezaki and colleagues,[18]who reported that females had a poorer response to peginterferon and ribavirin combination therapy than males among patients aged >50.The low tolerance to peginterferon and ribavirin and low estrogen levels in older women could be responsible for their impaired response.

The assessment of virological response at treatment week 4 is a simple and reliable tool for identifying patients most likely to achieve an SVR.[19]In this study,patients aged ≥65 who had achieved an RVR were more likely to get SVR (>80%) compared with those who had not.We found that RVR predicted SVR in a similar way in both patients aged ≥65 and those aged <65.Attainment of an RVR is the most powerful predictor of SVR,irrespective of age group and viral genotype.

To identify patients ≥65 (hard-to-treat population)who could particularly benefit from combination therapy,we studied the factors in fluencing SVR by multiple logistic regression analysis.We found some independent factors associated with SVR of patients aged ≥65,such as sex,genotype,ribavirin reduction or discontinuation and presence of RVR.Despite lower SVR rates in older patients,certain sub-groups,such as genotype 2 patients and genotype 1 patients with a low baseline viral load or achieving RVR or male,had high SVR rates (80.0%,53.0%,81.3%,and 47.6%,respectively).The strength of our findings may be enough to persuade some clinicians to offer antiviral therapy to these older patients,albeit with close monitoring.

In conclusion,compared with patients aged <65 years,the rate of ribavirin reduction or discontinuation and relapse rate of those aged ≥65 with genotype 1 are high,and the SVR rate is low.Age has no impact on virological response rates for genotype 2.We speculate that among patients ≥65,genotype 2 patients and genotype 1 patients with a low baseline viral load or achieving RVR or male may benefit from combination therapy.

Contributors:YJW and SLJ proposed the study.YJW wrote the first draft.SLJ analyzed the data.All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.SLJ is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Marcus EL,Tur-Kaspa R.Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in older adults.Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1606-1612.

2 Iwasaki Y,Ikeda H,Araki Y,Osawa T,Kita K,Ando M,et al.Limitation of combination therapy of interferon and ribavirin for older patients with chronic hepatitis C.Hepatology 2006;43:54-63.

3 Takaki S,Tsubota A,Hosaka T,Akuta N,Someya T,Kobayashi M,et al.Factors contributing to ribavirin dose reduction due to anemia during interferon alfa2b and ribavirin combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C.J Gastroenterol 2004;39:668-673.

4 Thabut D,Le Calvez S,Thibault V,Massard J,Munteanu M,Di Martino V,et al.Hepatitis C in 6865 patients 65 yr or older:a severe and neglected curable disease? Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1260-1267.

5 Manns MP,McHutchison JG,Gordon SC,Rustgi VK,Shiffman M,Reindollar R,et al.Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C:a randomised trial.Lancet 2001;358:958-965.

6 Fried MW,Shiffman ML,Reddy KR,Smith C,Marinos G,Gonçales FL Jr,et al.Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection.N Engl J Med 2002;347:975-982.

7 Koyama R,Arase Y,Ikeda K,Suzuki F,Suzuki Y,Saitoh S,et al.Efficacy of interferon therapy in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C.Intervirology 2006;49:121-126.

8 Antonucci G,Longo MA,Angeletti C,Vairo F,Oliva A,Comandini UV,et al.The effect of age on response to therapy with peginterferon alpha plus ribavirin in a cohort of patients with chronic HCV hepatitis including subjects older than 65 yr.Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1383-1391.

9 Honda T,Katano Y,Shimizu J,Ishizu Y,Doizaki M,Hayashi K,et al.Efficacy of peginterferon-alpha-2b plus ribavirin in patients aged 65 years and older with chronic hepatitis C.Liver Int 2010;30:527-537.

10 Reddy KR,Shiffman ML,Morgan TR,Zeuzem S,Hadziyannis S,Hamzeh FM,et al.Impact of ribavirin dose reductions in hepatitis C virus genotype 1 patients completing peginterferon alfa-2a/ribavirin treatment.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:124-129.

11 Foster GR,Fried MW,Hadziyannis SJ,Messinger D,Freivogel K,Weiland O.Prediction of sustained virological response in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a(40KD) and ribavirin.Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:247-255.

12 Bruchfeld A,Lindahl K,Schvarcz R,Stahle L.Dosage of ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C should be based on renal function:a population pharmacokinetic analysis.Ther Drug Monit 2002;24:701-708.

13 Snoeck E,Wade JR,Duff F,Lamb M,Jorga K.Predicting sustained virological response and anaemia in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD)plus ribavirin.Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:699-709.

14 Huang CF,Yang JF,Dai CY,Huang JF,Hou NJ,Hsieh MY,et al.Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon combined with ribavirin for the treatment of older patients with chronic hepatitis C.J Infect Dis 2010;201:751-759.

15 Reddy KR,Messinger D,Popescu M,Hadziyannis SJ.Peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kDa) and ribavirin:comparable rates of sustained virological response in sub-sets of older and younger HCV genotype 1 patients.J Viral Hepat 2009;16:724-731.

16 Honda T,Katano Y,Urano F,Murayama M,Hayashi K,Ishigami M,et al.Efficacy of ribavirin plus interferon-alpha in patients aged >or=60 years with chronic hepatitis C.J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:989-995.

17 Miller RA.Effect of aging on T lymphocyte activation.Vaccine 2000;18:1654-1660.

18 Sezaki H,Suzuki F,Kawamura Y,Yatsuji H,Hosaka T,Akuta N,et al.Poor response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin in older women infected with hepatitis C virus of genotype 1b in high viral loads.Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:1317-1324.

19 Yu JW,Wang GQ,Sun LJ,Li XG,Li SC.Predictive value of rapid virological response and early virological response on sustained virological response in HCV patients treated with pegylated interferon alpha-2a and ribavirin.J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:832-836.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Double inferior vena cava does not complicate para-aortic nodal dissection for the treatment of pancreatic carcinoma

- Cerebral protective effect of nicorandil premedication on patients undergoing liver transplantation

- Steroid elimination within 24 hours after orthotopic liver transplantation:effectiveness and tolerability

- Association of polymorphisms in non-classic MHC genes with susceptibility to autoimmune hepatitis

- Correlation of the occurrence of YMDD mutations with HBV genotypes,HBV-DNA levels,and HBeAg status in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B during lamivudine treatment

- Clinical outcome in patients with hilar malignant strictures type II Bismuth-Corlette treated by minimally invasive unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic biliary drainage