Elderly acute pulmonary thromboembolism initially presenting as syncope: a case report

2012-04-24金博,于凯,王春雷等

Elderly acute pulmonary thromboembolism initially presenting as syncope: a case report

(Department of Geriatrics, First Hospital, China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, China)

Case presentation

Yao, 80-year-old female, was admitted to the hospital due to the reduplicated disturbance of consciousness. One day before admission, the patient suddenly collapsed and lost consciousness for approximately 1 minute after oral hypotensor and micturition, without tic, incontinence, or bite injury of tongue. She came to Emergency Department of our hospital after her consciousness recovered spontaneously, as she felt weakness, diaphoretic and short of breath. Electrocardiogram (ECG) (emergency) and cardiac enzymes of serum were found normal. The patient refused to stay in Emergency Department for further observation before finishing intravenous nitroglycerine. The similar episode attacked 5 times after she went home.

Past medical history: the patient had hypertension and chest oppression for 30 years. The highest blood pressure was 17-180/80-90mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa), and she is using Valsartan to keep blood pressure between 130-140/70-80mmHg. She also had phlebeurysma of lower extremities for about 50 years.

Physical examination: T, 35.8℃, HR, 72 beats/min, BP: 80/0 mmHg. The patient’s consciousness was clear, the face and palpehra coniunetiva was pale, with cold extremities syndromes. There were no obvious rales. The superficial veins of lower shanks were bulgy. An ECG (Figure 1) showed ST segment in lead V1-V3lower 0.05 mV. cTnI: 1.22mg/L. Initial diagnosis: acute non-ST elevated myocardial infarction Killip I, cardiac syncope.

Providing rescue therapy such as oxygen, dilatation, elevating blood pressure, anticoagulant (subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin 4000IU once a day, total 7 days), antiplatelet (oral asprin 100mg once a day, oral clopidogrel 75mg once a day), stabilizing plaque (statin), protecting gastric mucosa and anti-inflammatory,, the patient’s life signs were recovered gradually.

Figure 1 ECG on 23rdJun

Sinus rhythm, HR: 75beats/min, Axis:-26°, ST segment in lead V1-V3lower 0.05mV, T waves in lead Ⅱ, Ⅲ, AVF and V1-V3were inverted 0.1-0.3 mV

On the 12th day of hospitalization, the patient suddenly felt chest oppression, shortness of breath and pericardial discomfort when she changed position. BP: 63/34mmHg, and ECG indicated multifocal atrial tachycardia (the most fast heart rate was 160 beats/min). Arterial blood gas: PaO2: 61.1mmHg, PaCO2: 36.3mmHg, PH: 7.373; D-D:>20mg/L; cTnI: 0.22ng/ml; CK: 82U/L, CK-MB: 26U/L, LDH: 1085U/L. It was considered to be acute pulmonary thromboembolism. Except for haemodynamic and respiratory support, the patient was asked to lie in bed, and anticoagulant was strengthened (oral warfarin 2.5mg once a day+subcutaneous low-molecular- weight heparin 4000IU once a day). Seventeen days later, the administration of low-molecular-weight heparin was stopped, and warfarin was modulated by 0.125mg to keep INR between 1.6-2.4.

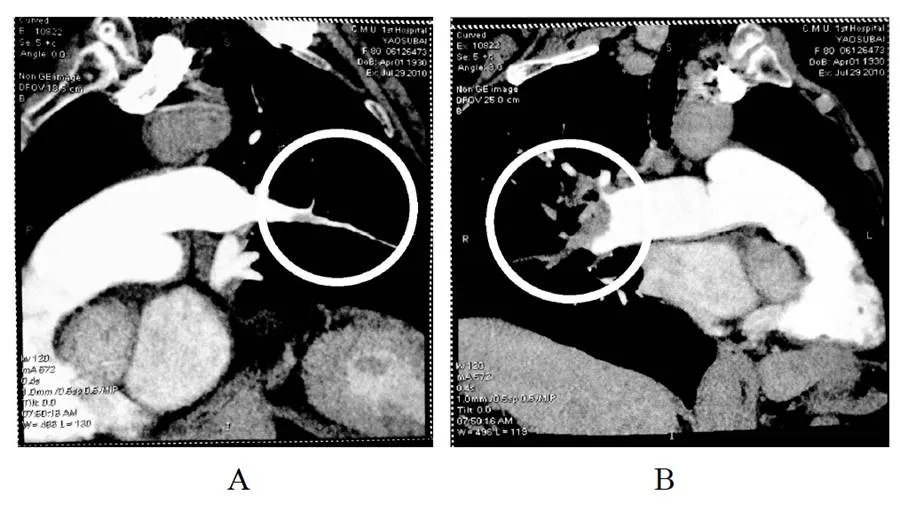

Thirty days after hospitalization, the patient’s condition was stable and auxiliary examinations were accomplished. Echocardiogram showed pulmonary arterial pressure elevated (60mmHg), echo of endocardium of left ventricular inferior wall enhanced, EF 57%. Color ultrasound of deep vein of both lower limbs showed plexus venosus leg muscle thrombosis. Pulmonary artery CT scan showed artery embolism of superior lobe, lobusmedius of right lung, and part branch arteries of superior lobe of left lung (Figure 2). Coronary artery CT showed no obvious abnormity in bilateral coronary arteries. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy was also performed: right pulmonary, developer of posterior segment of superior lobe and lobusmedius were deficient. Left pulmonary, developer of partial posterior segments of superior lobe apex, partial dorsal segments of inferior lobe, anterior basal segments were attenuated and filling-defect. Pulmonary blood ratio: left lung/total lung=59.10%, right lung/total lung=40.90% (Figure 3).

Figure 2 CTPA images on 29thJuly

A: Artery embolism of superior lobe, lobusmedius of left lung;B: part branch arteries of superior lobe of right lung

Figure 3 Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy on 9thAug

Right pulmonary: developer of posterior segment of superior lobe and lobusmedius were deficiency. Left pulmonary: developer of partial posterior segments of superior lobe apex, partial dorsal segments of inferior lobe, anterior basal segments were attenuated and filling-defect. Pulmonary blood ratio: Left lung/Total lung=59.10%, Right lung/Total lung= 40.90%

Sixty days after hospitalization, an intravenous filter was placed in the inferior vena cava to prevent further pulmonary thrombosis.

Definite diagnosis: (1) acute pulmonary embolism; (2) phlebeurysma of lower extremities (hibateral); (3) post-intravenous filter plantation; (4) hypertension degree 3 (extremely high risk).

Clinical Discussion

In this case, acute pulmonary thromboembolism initially presented as syncope, but not common dyspnoea, tachyphoea, or chest pain. Emergency ECG showed moving down of ST segment instead of right axis deviation or typical change of SⅠQⅢTⅢ. In addition, cardiac troponins and cardiac enzymes in serum were slightly elevated, which mislead to be acute cardiac infraction. Moreover, hypoxemia and plasma D-dimer could also be the result of cardiac infraction which makes initial differential diagnosis more difficult. The diagnosis was defined by pulmonary artery CT scan, coronary artery CT and color ultrasound of deep vein of both lower limbs after hospitalization. Although the indication for permanent inferior vena cava filter is classⅢ for patients with peripheral type of deep vein thrombosis who are undergoing antigoagulation therapy[1], color Doppler indicated her thrombosis was fresh enough to drop at anytime, associated with the history of reduplicated syncope and shock, permanent inferior vena cava filter was chosen.

This patient initially presented as syncope. Syncope is common in the general population, especially in the elderly who are over 65 years. The incidence of syncope shows a sharp rise after the age of 70 years, from 5.7 events per 1000 person-years to 11.1 events. Syncope in the elderly have its own specificities. (1) In the elderly, syncope occurring in the morning favors orthostatic hypotensor. (2) One-third of individuals over 65 years are taking three or more prescribed medications, which may cause or contribute to syncope. Withdrawal of these medications may reduce recurrences of syncope. (3) Cognitive impairment is present in 5% of 65 years old and 20% of 80 years old. This may attenuate the patients’ memory of syncope and falls. So, when the elderly were suspected to be cognitive impairment, the Mini-Mental State Examination should be performed except evaluation of neurological and locomotor systems[2].

The most common causes of syncope in the elderly are orthostatic hypotension, reflex syncope (especially carotid sinus syncope), and cardiac syncope (such as arrhythmia, acute myocardiac infarction, pulmonary embolism). Moreover, different causes often co-exist in a patient. Though rigorous steps and methods for syncope were established, only 58% of syncope events’ causes can be determined[3]. The incidence of syncope is less than 20% in acute pulmonary thromboembolism; however, it cannot be ignored because it is the sign of illness getting worse. There are 3 possible mechanisms of syncope in the setting of pulmonary thromboembolism. First, massive pulmonary thromboembolism can cause acute right ventricular failure, impaired left ventricular filling, tachycardia, hypotension, and result in the reduced cerebral perfusion. In some cases, this situation progresses to cardiac arrest. However, one must distinguish between 2 possible causes for systemic hypotension. The impaction of an embolus in a major pulmonary artery may elicit a Bezold-Jarisch type of reflex with hypotension and, perhaps, bradycardia and slow respiratory rate. This syncope is transient, lasting no more than 15 minutes after the onset of a massive pulmonary embolism. Prognosis during that period is difficult to evaluate because of the reflex hypotension and the tendency to spontaneous recovery. If hypotension persists, it is more likely to be the result of mechanical occlusion of pulmonary artery system which is an extremely prognosis sign. Second, pulmonary thromboembolism causes rapid or slow arrhythmias which results in hemodynamic instability, and might be due to reduction of cardiac diastolic function caused by pulmonary thromboembolism. Third, the pulmonary thromboembolism can trigger a vasovagal reflex and lead to syncope on a neurogenic basis[3].These three mechanisms can exist independently, and can also play a role together.

Pulmonary thromboembolism is a relatively common cardiovascular emergency. The death rates of acute pulmonary thromboembolism were as high as 7%-11%. The mean age of patients with acute pulmonary embolism is 62 years old, and the incidence increases exponentially with age and there is similar case for both idiopathic and secondary pulmonary thromboembolism. The patients with shock and hypotension are thought to be high-risk, as the in-hospital or 30-day mortality is over 15%[4]. The principle of treatment of acute pulmonary embolism is initially promising haemodynamic and respiratory support until it allows to choose thrombolysis, surgical pulmonary embolectomy, percutaneous catheter embolectomy and fragmentation. No matter what other therapy will be combined, anticoagulant should be used as soon as possible for highly suspected or diagnosed acute pulmonary thromboembolism except for patients at high risk of bleeding or with severe renal dysfunction. Thrombolysis can significantly reduce death or recurrence of patients with high risk acute pulmonary thromboembolism. In patients with absolute contraindications to thrombolysis, surgical embolectomy is the second choice and catheter embolectomy or thrombus fragmentation is the following consideration, though the safety and efficacy of such interventions has not been adequately documented. Intravenous unfractionated heparin should be the preferred mode of initial anticoagulation in patients with acute pulmonary thromboembolism at high risk, as low molecular weight heparin and fondaparinux have not been tested in the setting of hypotension and shock. The patient with shock and hypotension in this case was at high risk, but safer low molecular weight heparin is better for her according to HAS-BLED risk scores: >65 years, hypertension, history with anticoagulation administration. Long-term follow-up is recommended to this patient for better management of chronic disease.

(Translator: JIN Bo)

以晕厥为首发症状的老年急性肺栓塞1例

1 病例摘要

姚某某, 女, 80岁, 因“反复发作意识障碍1天”入院, 入院前1天, 患者口服降压药并排尿后突发意识不清, 近1 min, 无抽搐、排尿、排便失禁及舌咬伤, 神志自行恢复。但自觉乏力、冷汗、胸闷气短, 遂就诊于我院急诊科。急诊心电图、心肌酶正常。予硝酸酯类药物治疗, 患者拒绝急诊留观。回家后上述症状再发5次。患者既往有高血压, 胸闷30年, 血压最高达170~180/80~90 mmHg(1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa), 平素应用缬沙坦维持血压于130~140/70~80 mmHg; 双下肢静脉曲张50余年。入院查体: 体温35.8℃, 心率72次/min,血压80/0 mmHg; 神志尚清, 面色及睑结膜苍白, 四肢发凉, 双肺未闻及干湿啰音, 双小腿浅表静脉突出于皮肤表面; 心电图: V1~V3导联ST段下移0.05 mV(图1); cTnI 1.22 µg/L。初步诊断: 急性非ST段抬高性心肌梗死Killip I级, 心源性休克。给予吸氧、扩容、升压、抗凝(低分子肝素4000 IU, 每日1次皮下注射, 疗程7 d)、抗血小板聚集(阿司匹林0.1 g, 每日1次口服, 氯吡格雷75 mg, 每日1次口服)、稳定斑块(他汀类药物)、抗炎、保护胃黏膜等抢救措施后, 患者各项生命指征平稳。

入院第12 d, 患者被动改变体位时突发胸闷气短、心前区不适, 血压63/34 mmHg, 心电图示紊乱性房性心律失常(最高心率160次/min)。急检动脉血气: PaO261.1 mmHg, PaCO236.3 mmHg, pH 7.373; D-二聚体>20 mg/L; cTnI 0.22 µg/L; CK 82 U/L, CK-MB 26 U/L, LDH 1085 U/L, 考虑为急性肺栓塞, 除给予呼吸道和血流动力学支持外, 嘱患者绝对卧床, 并加强抗凝治疗(华法林2.5 mg, 每日1次口服+低分子肝素4000 IU, 每日1次皮下注射)。17d后停用低分子肝素, 以0.125 mg为单位调整华法林的剂量, 维持国际标准化比值于1.6~2.4。

入院30 d后, 患者病情平稳, 开始进行相关检查。经胸超声心动图示: 肺动脉压力升高(60 mmHg), 左室下壁心内膜回声增强, 射血分数57%; 双下肢深静脉彩超示: 双小腿肌间静脉可见血栓形成; 肺动脉CT血管造影示: 右肺上叶、中叶肺动脉栓塞, 左肺上叶肺动脉局部分支栓塞(图2); 冠脉CT示: 两侧冠状动脉未见明显异常; 肺通气-血流灌注显像示: 右肺上叶后段、中叶见显像剂分布缺损, 左肺部分上叶尖后段、部分下叶背段、前底段见显像剂分布稀疏缺损区, 肺血流比异常, 左肺/全肺= 59.10%, 右肺/全肺= 40.90%(图3)。

入院60 d后, 为防止再次发生肺栓塞, 患者接受了下腔静脉滤器植入术。

出院诊断:(1)急性肺栓塞;(2)下肢静脉曲张(双侧), 深静脉血栓(双小腿肌间静脉);(3)下腔静脉滤器植入术后;(4)高血压病3级(极高危险组)。

2 临床病例讨论

金博住院医师: 本例急性肺血栓栓塞症的临床表现并非常见的胸痛、气促、呼吸困难, 而表现为晕厥, 心电图无电轴右偏、SIQⅢTⅢ的典型改变, 而表现为ST段下移, 同时血清肌钙蛋白和心肌酶轻度升高, 极易与心肌梗死混淆, 而低氧血症、血浆D-二聚体升高也可由心肌梗死造成, 更使二者的初步鉴别异常艰难。入院后完善肺动脉CT血管造影、冠状动脉CT、双下肢深静脉彩超等检查才明确诊断。需指出, 下肢远端静脉血栓植入永久性下腔静脉滤器为Ⅲ类推荐[1], 但超声显示该患者的下肢血栓较为新鲜, 随时有脱落的可能, 结合患者有反复晕厥及休克的病史, 遂为患者植入了永久性下腔静脉滤器。

于凯主治医师: 该患者以晕厥为首发症状。晕厥在人群中, 特别是在65岁以上的老年人中发生很普遍, 当年龄超过70岁时, 晕厥的发生率会从每年的5.7‰上升至11.1‰, 而且老年人的晕厥具有自身的特点:(1)在老年人中, 发生于清晨的晕厥多为直立性低血压型; (2)在65岁以上的老年人中, 有超过1/3的患者应用3种或3种以上的处方药, 暂停这些药物可能会减少晕厥的发生; (3)有5%>65岁老年人和20%>80岁老年人存在认知功能障碍, 有时他们并不能区分晕厥和跌倒。因此对于老年人, 除了评价神经、运动系统外, 对怀疑有认知障碍者, 应进行简易精神状态检查[2]。

王春雷副主任医师: 老年人晕厥的病因多为体位性低血压、反射性晕厥(尤其是颈动脉窦综合征)和心源性晕厥(如心律失常、急性心肌梗死、肺栓塞等), 而且同一个患者可能同时存在几种病因。虽然人们为晕厥制定了严谨的评价步骤和方法, 但仅有58%的晕厥事件能够找到确切的病因[3]。晕厥在肺栓塞中的发生率不足20%, 但其预示着病情的危重, 在明确病因时不可忽视。肺栓塞导致晕厥的机制有以下3点: (1)大块肺动脉栓塞引起急性右心衰竭、左室充盈减少、心动过速、血压下降, 从而导致脑供血不足。在某些病例中, 这种情况可出现心脏停搏。在这种机制中包含两种导致系统性低血压的原因: 肺动脉主干被栓子压迫引起Bezold- Jarisch反射和肺动脉系统闭塞。Bezold-Jarisch反射导致低血压, 可伴有心动过缓和呼吸节律缓慢, 此类晕厥是短暂的, 持续时间不超过发生大块肺栓塞后的15 min, 在这期间很难判断患者的预后, 因为此时的低血压为反射性的, 并有自主恢复的趋势; 如果低血压状态持续存在, 则更像是肺动脉系统闭塞所致。(2)肺动脉栓子引起快速型或缓慢型心律失常, 导致血流动力学不稳定, 这种情况被认为是由肺动脉栓子降低了心脏的舒张性所致。(3)肺动脉的栓子引起了某种血管反射, 从而导致了神经源性晕厥[3]。3种机制可以单独存在, 也可以联合发挥作用。

白小涓主任医师: 肺栓塞是一种相对高发的心血管急症。急性肺栓塞的病死率高达7%~11%, 发病的平均年龄为62岁, 而且随着年龄的增长, 原发性和继发性肺栓塞的发病率均呈指数级上升。伴有休克和低血压的肺栓塞患者, 危险分层为高危组, 即在住院期间或30 d内因肺栓塞死亡的概率大于15%[4]。急性肺栓塞的治疗原则是在提供呼吸和血流动力学支持的基础上, 选择溶栓、外科栓子清除术、经皮导管栓子清除和碎裂术。对于高度怀疑或确诊的急性肺栓塞患者, 无论是否合并其他治疗策略, 都应立即进行抗凝治疗, 除非患者是出血的高危人群或存在严重的肾功能不全。溶栓术可明显减少高危患者的死亡率和栓塞再发率, 当存在溶栓的绝对禁忌时, 依次选择外科栓子清除术和经皮导管栓子清除和碎裂术, 但后者的安全性和有效性还缺乏足够的文献证实。因为尚缺乏低分子肝素和磺达肝癸钠在此类人群中的实验数据, 高危患者的抗凝推荐使用普通肝素。本例急性肺栓塞患者, 伴有休克和低血压, 危险分层为高危组, 但其年龄>65岁, 有高血压病史, 有抗凝药使用史, 根据HAS-BLED出血风险评分[5], 为出血的高危人群, 因此使用出血风险低的低分子肝素单纯抗凝更适合该患者。建议对该患者进行长期随访, 做好慢病管理。

[1] Yamada N, Nakamura M, Ito M,.Currentstatus and trends in the treatment of acutepulmonary thromboembolism[J]. Circ J, 2011, 75(12): 2731-2738.

[2] Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F,Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009)[J]. Eur Heart J, 2009, 30(21): 2631-2671.

[3] Koutkia P, Wachtel TJ. Pulmonary embolism presenting as syncope: case report and review of the literature[J]. Heart Lung, 1999, 28(5): 342-347.

[4] Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S,Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)[J]. Eur Heart J, 2008, 29(18): 2276-2315.

[5] Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY,. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)[J]. Eur Heart J, 2010, 31(19): 2369-3429.

(参与讨论医师: 金 博, 于 凯, 王春雷, 白小涓)

(金 博整理)

(编辑: 任开环)

2011-11-03;

2012-01-14

白小涓, Tel: 024-83282770, E-mail: xjuanbai@hotmail.com

R543.2

A

10.3724/SP.J.1264.2012.00058