Laparoscopic liver resection for benign and malignant liver tumors

2011-07-07AshishSinghalYiHuangandVivekKohli

Ashish Singhal, Yi Huang and Vivek Kohli

Oklahoma, USA

Original Article / Liver

Laparoscopic liver resection for benign and malignant liver tumors

Ashish Singhal, Yi Huang and Vivek Kohli

Oklahoma, USA

BACKGROUND:Laparoscopic liver resection is one of the most complex procedures in hepatobiliary surgery. In the last two decades, laparoscopic liver surgery has emerged as an option at major academic institutions. The purpose of this study is to describe the initial experience of minimally invasive liver resections at a non-academic institution.

METHODS:We retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients undergoing laparoscopic liver resections between June 2006 and December 2009 at our center. Indications, technical aspects, and outcomes of these patients are described.

RESULTS:Laparoscopic liver resection was attempted in 28 patients. Of these, 27 patients underwent laparoscopic liver resection (22 total laparoscopic and 5 hand assisted) and one needed conversion to open surgery. Twenty patients had a benign lesion and 8 had malignant lesions. Three patients had multiple lesions in different segments requiring separate resections. The lesions were located in segments II-III (n=18), IV (n=3), V-VI (n=9), and VII (n=1). Tumor size ranged from 1.5 cm to 8.5 cm. The surgical procedures included left lateral sectionectomy (n=17), left hepatectomy (n=2), sectionectomy (n=8), and local resections (n=4). Median operative time was 110 minutes (range 55-210 minutes), and the median length of hospital stay was 2.5 days (range 1-7 days). There was no perioperative mortality. One patient developed hernia at the site of tumor extraction requiring repair at 3 months.

CONCLUSIONS:Laparoscopic liver resections can be safely performed in selected patients with benign and malignant liver tumors. With increasing experience, laparoscopic liver resections are likely to become a favorable alternative to open resection.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 38-42)

hepatectomy; liver neoplasm; liver surgery

Introduction

The first successful laparoscopic partial hepatectomy was performed by Gagner et al[1]in 1992 for a patient with focal nodular hyperplasia. Four years later, Azagra et al[2]reported the first anatomical laparoscopic left lateral segmentectomy. Over the past 15 years, liver resections were introduced into clinical practice based on case series, which demonstrated the usual benefits of minimally invasive procedures, without loss of efficacy of the operations. However, the feasibility of laparoscopic liver surgery was better acknowledged following a prospective study by Cherqui et al.[3]Since this initial report, several centers have reported larger laparoscopic series containing many hemihepatectomies for primary and secondary tumors in both cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic livers, including right lobe liver resection for adult-to-adult living-related donation for transplantation.[4]However, laparoscopic liver resections are still on the early part of the adoption curve.

Between June 2006 and December 2009, we performed laparoscopic liver resections in 28 patients with liver neoplasm, the results of which were encouraging. The purpose of this study is to report our experience and outcomes of laparoscopic liver resections.

Methods

Between June 2006 and December 2009, laparoscopic liver resection was attempted in 28 patients. Indications for liver resection include malignant tumor, benign tumor with malignant potential, symptomatic benign tumor, and growing tumor with unclear radiological diagnosis. The patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery for cystic liver lesions (unroofing or resection) and radiofrequency ablation were excluded from this study. The institutionalreview board at the INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center, Oklahoma City approved this study.

Institutional organizational structure

The Nazih Zuhdi Transplant Institute (NZTI) is part of a 508-bed non-academic, tertiary care facility (INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center), offering a comprehensive multi-organ transplant program for both thoracic and abdominal organs. As transplantation requires a multidisciplinary care, the NZTI has been successfully practicing an integrated organizational structure since 1992. The institutional structure was modeled on the principles of a pyramid consisting of a core component, a multidisciplinary full-time component, and an outsourced component.[5]Since the inception of a transplant program for each organ, 2378 solid organ transplants have been done until December 2008. At various time-points, the patient and graft survival rates were higher than the respective US national averages.

Preoperative assessment was carried out with history and physical evaluation, liver function test, contrast enhanced CT scan or contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. The selection for laparoscopic approach was based on: 1) the characteristics of tumor (peripheral and located in anterior sectors), 2) the number and size of lesions (solitary tumor and <10 cm), and 3) the experience of the surgical team. All resections were performed by single primary surgeon (Kohli V). Contraindications for laparoscopic liver resection were general contraindications for laparoscopic approach and underlying cirrhosis. The following parameters were evaluated: age, sex, preoperative and postoperative diagnosis, indication for resection, number, size and location of tumors, type of resection performed, parenchymal transection technique, operative time, conversion rate, length of stay, morbidity, mortality, and long-term outcomes.

The approach was defined as "total laparoscopic" if the resection was completed without conversion to "hand assisted" or open surgery. When a hand was introduced through a hand port, the approach was defined as "hand assisted laparoscopic". Selection of approach was based on tumor characteristics (number, size, and location) and intraoperative findings.

Surgical procedure

All resections were performed with the patient in the supine position under general endotracheal anesthesia. For right lobe lesions, the surgeon stood on the left side of the patient, the first assistant and the camera assistant on the right side. For left sided lesions the positions were reversed. Pneumoperitoneum was created through the umbilicus using Hasson technique and controlled at a constant intrabdominal pressure of 12 mmHg. A 10-mm 30° laparoscope was placed through the umbilical port for abdominal exploration. Additional 5 or 12 mm trocars were placed at sites depending on the location of the liver lesion. For right-sided lesions, a hand port (GelPort, Applied Medical Resources Corp, CA, USA) was positioned via a subcostal incision. Mobilization of the liver was achieved by dividing the ligamentous attachments as necessary for the respective resections. It was not necessary to achieve full mobilization for lesions located at the edge of the liver. Laparoscopic ultrasound with a 7.5 MHz transducer (Aloka Prosound, Wallingford, CT, USA) was used in all cases to help localize the tumors, demarcation of vascular structures, demonstration of satellite nodules (if any), and demarcation of an adequate tumor-free margin.

Transection of liver parenchyma was done using an ultrasonic based energy device in the first five resections. Subsequent resections were done using EnSeal, a radiofrequency energy based device (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc, Cincinnati, OH, USA). This permitted sealing of vessels and biliary channels up to 7 mm in diameter. Larger vascular structures encountered were divided using an endoscopic linear stapler (Covidien Autosuture, Mansfield, MA, USA). Hemostasis on the divided liver surface was achieved by coagulation using a laparoscopic argon beam coagulator, Bioglue, a fibrin glue sealant (CryoLife, Inc, Kennesaw, GA, USA), and suturing whenever necessary. The resected specimen was placed inside a large plastic bag and subsequently removed through the enlarged umbilical incision or through the incision for the hand-assisted device.

Surgical complications, blood loss, length of hospital stay, and time to return to work were recorded. No patient was lost at follow-up.

Results

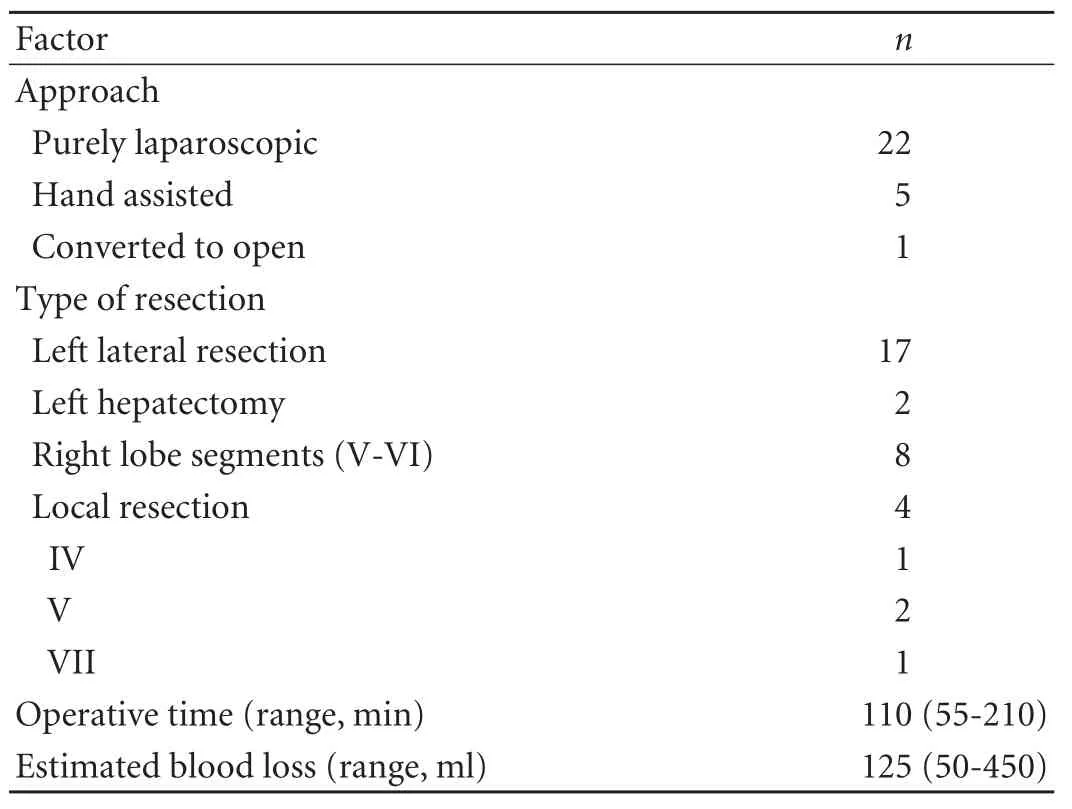

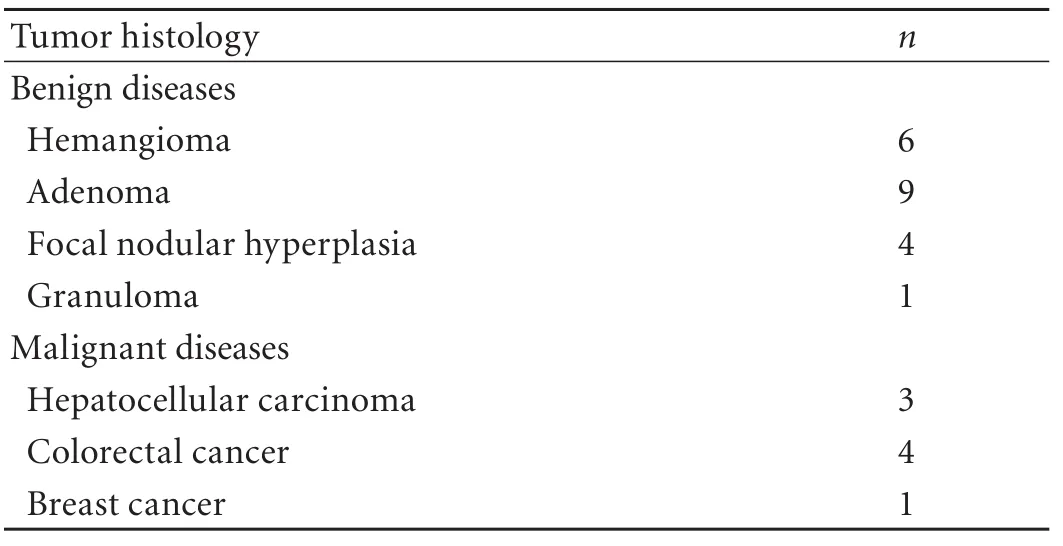

Laparoscopic liver resection was attempted in 28 patients (10 men and 18 women) with a median age of 36 years (range 19-72 years). Preoperative liver functions classified all patients as Child's A.[6]The median size of the lesions was 5 cm (range 1.5-8.5 cm)(Fig. 1). Patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Thirty-one lesions were resected among the 28 patients. Three patients had multiple lesions. The types of resections included left lateral sectionectomy in 17 patients, left hepatectomy in 2, sectionectomy in 8, and local resections in 4. Details of types of laparoscopic hepatectomy are illustrated in Table 2. A total laparoscopic resection was done in 22 patients(78.6%), hand assisted in 5 (17.9%), and conversion to open surgery in 1. The specimen was removed through an enlarged umbilical incision in 22 patients and through the incision for the hand port in 5. The median operative time was 110 minutes (range 55-210 minutes). The median estimated blood loss was 125 ml (range 50-450 ml); none of the patients received blood transfusion. Twenty patients (71.4%) had benign disease and 8 patients (28.6%) had malignant disease. Details of histological results are summarized in Table 3. In all patients with malignant lesion (primary or metastatic), a R0 resection was made.

Table 1. Patient and tumor characteristics

Table 2. Operative details

Table 3. Histological details

Fig. 1. A: CT scan showing a large adenoma in right lobe of liver; B: Laparoscopic view of large adenoma involving right lobe of liver (inferior surface).

Fig. 2. A: Laparoscopic transection of right lobe tumor; B: Postresection laparoscopic view.

One patient developed intraoperative pneumothorax during mobilization of the right lobe requiring chest tube placement and diaphragmatic repair. There were no perioperative deaths. None of the patients received perioperative transfusions. No biliary leaks were noted. Liver function returned to normal within 1 week. The median postoperative hospital stay was 2.5 days (range 1-7 days). At the first postoperative visit at 1 month, all patients had resumed normal activities and 20 (71.4%) patients returned to full-time work. The median followup was 26 months (range 3-42 months). No port site metastasis or recurrence was noted during follow-up in patients who had hepatectomy for malignant lesions (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Initially, laparoscopic liver resection was viewed with skepticism because of concerns regarding parenchymal transection, bleeding control, bile leakage, and incomplete resection, and removal of resected specimens.[7-9]However, nowadays, with the adequate technology and appropriate surgical skills, nonvoluminous malignant or benign lesions located in the left lateral (II, III) and the anterio-inferior liver sectors (IVB, V, and VI) constitute ideal cases for the laparoscopic approach.[3,4,7,8-16]In the present series, 97% of the lesions were located in these sectors. However, resections of tumoral lesions for the posterior and superior sectors (I, IVa, VII, and VIII) have also been described.[8,16]

The size, number, and location of lesions determine the suitability for a laparoscopic approach. The majority of patients (89%) had single lesions. Overall, the median size of the lesions was 5 cm (range 1.5-8.5 cm). A neoplasm less than 6 cm in size is thought to be preferred.[17]We performed laparoscopic resection in 2 patients with neoplasms more than 8 cm in size in the left liver lobe without invasion of vascular structures. In our cohort, only one patient needed conversion to laparotomy because of technical difficulties in detecting additional lesion in segment VII-VIII area.

One of the main concerns during hepatectomy is minimization of intraoperative blood loss and thereby avoiding use of blood products. In our experience, laparoscopic surgery provided better visualization of deep vascular structures and more precise and accurate surgery. The median estimated blood loss was 125 ml and no patient required blood transfusion. To avoid injury to the hepatic veins, caution should be taken during manipulation and dissection of these structures. The hepatic veins should be transected in the parenchyma using clips or an endoscopic linear stapler. Control of the hepatic veins is probably the moment of greatest risk in laparoscopic liver surgery. Injury of the hepatic veins has been reported as an important cause of conversion.[18]Parenchymal transection represents another major challenge to advance in these resections. Earlier bleeding during parenchymal transection due to a lack of effective devices was an important cause of blood loss, but there are now numerous excellent devices for dividing the parenchyma, including ultrasonic scalpel, microwave tissue coagulator, water jet dissector, LigaSure, cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA), argon beam coagulator, Peng's Multifunction Operative Dissector, and TissueLink. Based on our experience, using an ultrasonic scalpel and Enseal to transect the liver facilitates good hemostasis, clear anatomy, less effusion, and minimal damage to residual liver tissue. Simultaneously, we emphasize the importance of keeping the central vein pressure below 5 mmHg to minimize bleeding during the hepatic parenchymal transection. Gas embolism caused by pneumoperitoneum during hepatic vein division is another potential risk.[19]Although this complication appears to be rare, we utilize several precautions to avoid embolic events, including careful dissection of the hepatic vein, a low-pressure pneumoperitoneum (10-12 mmHg), and use of the endovascular stapler to transect the hepatic veins.

Achievement of a tumor-free margin while resecting a malignant neoplasm is an important concern for the limited use of laparoscopic liver resection. Mala et al[20]reported the same rate of negative surgical margins after laparoscopic and open liver resections. A European multicenter study showed that there was no evidence that the use of a laparoscopic technique increases the risk of local recurrence or port-site metastases.[13]We believe that a 1-cm tumor-free surgical margin can be obtained with laparoscopic resection. Further, routine use of intraoperative laparoscopic ultrasound helps to demarcate the line of resections and compensates for the loss of tactile sensation. Intraoperative ultrasonography is mandatory for tumor identification and margin control. It should be used at the beginning of the procedure to confirm and precisely locate the tumors, to exclude undetected tumors, and to map the vascular and biliary anatomy. In the present series no patient had positive margins, and all patients undergoing resections for malignant tumors remain disease free.

Recent studies have shown that laparoscopic liver surgery offers the same benefits over open surgery as other forms of minimally invasive surgery.[18,21,22]These benefits include less pain, better cosmesis, shorter length of hospital stay, and rapid recovery. Laparoscopic resection has the advantage of minimal scarring and fewer adhesions, thereby increasing the ease and feasibility of repeat liver resection when needed. Furthermore, the morbidity and mortality for laparoscopic surgery are equivalent to large case series of open major liver resection and the oncologic goals of such resections are maintained.[18,21,22]Twenty (71.4%) of 28 patients in our study cohort returned to full-time work by the first postoperative visit at one month. There was only one complication that might be directly attributable to laparoscopic surgical technique--intraoperative pneumothorax.

Lastly, we advocate laparoscopic liver resection as a complex procedure that requires experience and skills different from those of open surgery. However, skills for open liver resection remain an essential component. Therefore, in contrast to small, asymptomatic focal nodular hyperplasia, hemangioma, and granulomas, which usually do not require resection, laparoscopic liver resection remains a good option in appropriately selected patients with large, symptomatic, and growing tumors with unclear radiological or histological diagnosis.

In conclusion, laparoscopic liver resections for benign and malignant hepatic tumors, performedby surgeons with adequate training and in selected patients are safe and effective. It is associated with a low morbidity and mortality. Combined with the use of intraoperative laparoscopic ultrasound, an R0 resection is achievable. Long-term survival after laparoscopic resection is comparable to that after open resection.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:KV proposed the study. SA wrote the first draft. SA and KV analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. KV is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Gagner M, Rheault M, Dubuc J. Laparoscopic partial hepatectomy for liver tumor. Surg Endosc 1992;6:97-98.

2 Azagra JS, Goergen M, Gilbart E, Jacobs D. Laparoscopic anatomical (hepatic) left lateral segmentectomy-technical aspects. Surg Endosc 1996;10:758-761.

3 Cherqui D, Husson E, Hammoud R, Malassagne B, Stéphan F, Bensaid S, et al. Laparoscopic liver resections: a feasibility study in 30 patients. Ann Surg 2000;232:753-762.

4 Koffron AJ, Auffenberg G, Kung R, Abecassis M. Evaluation of 300 minimally invasive liver resections at a single institution: less is more. Ann Surg 2007;246:385-394.

5 Jabbour N, Singhal A, Ghuloom AE, Monlux RD, Bag R, Dugan R, et al. Multiorgan transplant program in a nonacademic center: organizational structure and outcomes. Prog Transplant 2010;20:234-238.

6 Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646-649.

7 Morino M, Morra I, Rosso E, Miglietta C, Garrone C. Laparoscopic vs open hepatic resection: a comparative study. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1914-1918.

8 Vibert E, Perniceni T, Levard H, Denet C, Shahri NK, Gayet B. Laparoscopic liver resection. Br J Surg 2006;93:67-72.

9 Buell JF, Thomas MJ, Doty TC, Gersin KS, Merchen TD, Gupta M, et al. An initial experience and evolution of laparoscopic hepatic resectional surgery. Surgery 2004;136: 804-811.

10 Buell JF, Koffron AJ, Thomas MJ, Rudich S, Abecassis M, Woodle ES. Laparoscopic liver resection. J Am Coll Surg 2005;200:472-480.

11 Dagher I, Proske JM, Carloni A, Richa H, Tranchart H, Franco D. Laparoscopic liver resection: results for 70 patients. Surg Endosc 2007;21:619-624.

12 Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Stabilini C, Berticelli J, Mahajna A. Laparoscopic liver resections: a single center experience. Surg Endosc 2005;19:886-891.

13 Gigot JF, Glineur D, Santiago Azagra J, Goergen M, Ceuterick M, Morino M, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection for malignant liver tumors: preliminary results of a multicenter European study. Ann Surg 2002;236:90-97.

14 Kaneko H. Laparoscopic hepatectomy: indications and outcomes. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2005;12:438-443.

15 Katkhouda N, Hurwitz M, Gugenheim J, Mavor E, Mason RJ, Waldrep DJ, et al. Laparoscopic management of benign solid and cystic lesions of the liver. Ann Surg 1999;229:460-466.

16 Vibert E, Kouider A, Gayet B. Laparoscopic anatomic liver resection. HPB (Oxford) 2004;6:222-229.

17 Kaneko H, Takagi S, Otsuka Y, Tsuchiya M, Tamura A, Katagiri T, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Surg 2005;189:190-194.

18 Clariá RS, Ardiles V, Palavecino ME, Mazza OM, Salceda JA, Bregante ML, et al. Laparoscopic resection for liver tumors: initial experience in a single center. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2009;19:388-391.

19 Takagi S. Hepatic and portal vein blood flow during carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic hepatectomy. Surg Endosc 1998;12:427-431.

20 Mala T, Edwin B, Gladhaug I, Fosse E, S?reide O, Bergan A, et al. A comparative study of the short-term outcome following open and laparoscopic liver resection of colorectal metastases. Surg Endosc 2002;16:1059-1063.

21 Zhang L, Chen YJ, Shang CZ, Zhang HW, Huang ZJ. Total laparoscopic liver resection in 78 patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:5727-5731.

22 Kazaryan AM, Pavlik Marangos I, Rosseland AR, R?sok BI, Mala T, Villanger O, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection for malignant and benign lesions: ten-year Norwegian singlecenter experience. Arch Surg 2010;145:34-40.

September 29, 2010

Accepted after revision December 19, 2010

Author Affiliations: Nazih Zuhdi Transplant Institute, INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center, 3300 NW Expressway, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73112, USA (Singhal A, Huang Y and Kohli V)

Vivek Kohli, MD, Nazih Zuhdi Transplant Institute, INTEGRIS Baptist Medical Center, 3300 NW Expressway, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73112, USA (Tel: 001-405-949-3349; Fax: 001-405-945-5844; Email: Vivek.Kohli@integrisok.com)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Expression oflamino acid transport system 1 and analysis of iodine-123-methyltyrosine tumor uptake in a pancreatic xenotransplantation model using fused high-resolution-micro-SPECT-MRI

- Assessment of tumor vascularization with functional computed tomography perfusion imaging in patients with cirrhotic liver disease

- Monday blues of deceased-donor liver transplantation

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Roles of sulfonylurea receptor 1 and multidrug resistance protein 1 in modulating insulin secretion in human insulinoma

- Atypical focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver