德国西宁根与中国灵井的骨器比较

2024-06-30王华李占扬ThijsvanKOLFSCHOTEN

王华 李占扬 Thijs van KOLFSCHOTEN

摘要:相似性在人类体质、文化和技术等方面的演化过程中扮演着非常重要的角色。本文涉及到的两个遗址,位于德国的旧石器时代早期遗址西宁根13 地点II-4 层和位于中国北方地区的旧石器时代中期灵井遗址10-11 层,出土的考古遗存具有极大的相似性。两个遗址保存状况都非常好,且均出土有大量的石器和动物化石。最为引人注意的是,两个遗址出土的动物遗存特点以及骨器相关的遗存也表现出多个方面的相似性。经鉴定,两个遗址均出土有多个种属的食肉动物、一种象,两种犀牛属动物、两种马科动物,多种鹿类以及牛科动物。两个遗址均出土有修整石器所用的骨质软锤,以及利用食草动物的掌跖骨制作的用于砸骨吸髓的骨锤。这些锤子的远端具有特定的破裂形态。考虑到两个遗址之间的距离以及年代差异,这些相似性非常值得关注,但我们不认为两个遗址的相似性代表的是文化上的联系。相反,我们认为这种相似性反映的是人类在相似的环境中采取了相似的行为模式,同时相似的埋藏条件也起到一定的作用。

关键词:旧石器时代;露天遗址;骨器;中国;欧洲

Comparison of bone artifacts from the Sch?ningen site in Germany and the Lingjing site in China

Abstract: Similarities play an important role in the reconstruction of human physical, culturaland technological evolution. The two sites presented in this paper, the Middle Palaeolithic siteLingjing in China Layer 10 and 11 and the Lower Palaeolithic site Sch?ningen 13 II-4, the socalledSch?ningen Spear Horizon in Germany, show striking similarities. The archaeologicalrecord of both sites includes lithic artifacts as well as a very large assemblage of fossil bones.The preservation of the material at both sites is excellent and the faunas encountered at bothsites show many similarities. The faunal lists of both sites include a diverse carnivore guild, anelephant species, two different rhinoceros species, two different equids, different cervids andlarge bovids. Both sites also yielded bone retouchers as well as a unique record of bone hammersthat show identical, unusual flaking and percussion damage

These similarities are remarkable if one takes into account the difference in age (ca 200 kaBP)and the geographical distance between the two sites of ca 8000 km. Therefore, we do not assumea close cultural link between the hominin populations active at both sites. The authors assumethat the observed similarities show more or less identical, opportunistic hominin behaviour atboth sites located in a comparable environment with more or less similar taphonomic conditions.

Keywords: Palaeolithic; open-air sites; bone tools; Asia; Europe

1 Introduction

The archaeological record shows that the history of humans extends back over 3 MaBP. Arecord that is very diverse as well as fragmented; major elements of the “jigsaw puzzle” are therelatively small amount of hominin remains and a large amount of artificially modified stones andbones. But also other proxies such as living structures or the accumulation of prime-adult preyanimals that indicate human interference, offer insight into the evolutionary history of humansand their cultural development[1-4].

The morphological features of the human remains, combined with chronostratigraphicalevidence, and since a few decades, also in combination with fossil biomolecular (genetic)information, form the base of the tree that shows the human evolutionary history[5]. The largenumber of Palaeolithic sites provides insight into the early dispersal of hominins within Africa,as well as, after leaving Africa about 1.8 MaBP, beyond the continent. The geographical spreadof Humans over the globe is rather well known despite the relatively low number of sites, thefragmented record from which shows many stratigraphical hiatuses. However, specific detailsconcerning hominin dispersal, such as the routes they took entering Europe, remain unclear.

The study of human behavioural evolution is mainly focused on the stone and bone toolsencountered at archaeological sites. They are the only record of our technological heritage thatindicates humans capacity for innovation and hence, tools are very important for the decipheringof our cultural development[6]. The use of (artificially modified) stone tools most probablyextends back more than 3 MaBP[7]. The Palaeolithic stone tool record shows progressive changesfrom simple stone flakes and hammer stones, followed by the addition of handaxes succeeded bya wide array of technological and cultural traditions[5].

Compared to stone tools, bone tools are less common in the archaeological record. SouthAfrican sites yielded the oldest bone tools (elongated bone fragments with wear patterns that have been interpreted as digging tools) dated to between 2 MaBP and 1.4 MaBP[8,9]. At around 0.5 MaBP,hominins began to use antlers and large mammal limb bones to manufacture and maintain lithic tools[10].

The ultimate challenge of Palaeolithic research is to complete the picture that shows us ourphysical and cultural history, by linking the isolated pieces. When we are able to link specificjigsaw puzzle pieces and add an age component, we might be able to decipher for examplemigration patterns and we might get a clue to our regional cultural evolution. Similarities play animportant role in that process. The Palaeolithic record of the sites at the Sch?ningen in Germanyis characterised by an unique set of bone hammers[10,11] and it was a big surprise to encounter inthe bones collection from the Lingjing site in China with modification features that are almostidentical to those observed at the Sch?ningen bone hammers. This remarkable because bonehammers are rare in the archaeological record. It is even more remarkable if one takes intoaccount the large geographical distance between the two sites, located virtually at the oppositeedges of the Eurasian continent, and the major difference in age of the record. In order tounderstand the observed similarities a more detailed comparative study has been initiated and theresults of this study are presented in this paper. The sites and the archaeological record of bothsites are briefly presented and the unique bone culture, encountered at both sites, is highlighted,compared and discussed.

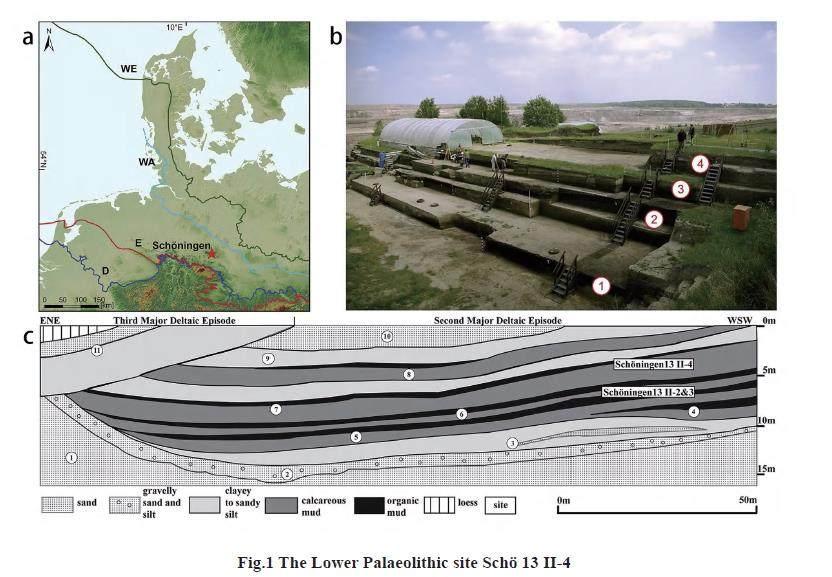

2 Sch?ningen in Germany

Sch?ningen (52o08'N, 10o57'E) is a small town located in northern Germany, north of thefoothills of the Harz mountains and at the edge of a region with remnants of huge open-castlignite quarries. In order to access the Tertiary lignite, the overlying succession of late Quaternarydeposits has been removed. The base of the Quaternary deposits, exposed in the Sch?ningenopen-cast mine, is formed by a till, deposited during the Elsterian Stage glaciation. A successionof lacustrine deposits with a thickness of up to 7.5 m, separates the Elsterian and the overlyingSaalian-age tills[12,13]. These lacustrine deposits have yielded a sequence of 5-6 stratigraphicallysuperimposed horizons and a large number of spatially distributed archaeological sites withPalaeolithic artifacts and botanical as well as faunal remains. At least 20 Lower Palaeolithic siteshave been excavated so far[14]. The majority of the sites date from the locally defined late MiddlePleistocene Reinsdorf Interglacial which is equated to Marine Isotope Stage 9 (MIS 9), a periodfrom 320 kaBP to 300 kaBP[15,16].

The Sch?ningen lower Palaeolithic site (Sch? 13 II-4 also known as the ‘Spear Horizon)(Fig.1) is most famous because of the discovery of wooden spears by Dr. Hartmut Thieme in1995[17]. The site has an excavated surface of 3783 m2 and has yielded over 15,000 recordedlarger finds[14]). The archaeological assemblage from the site Sch? 13 II-4 includes among theca 740 wooden objects[14] at least nine spears/spear fragments, one lance, one double pointed rod (also known as a wooden throwing stick[18]) and one burnt worked wooden stick[19]. The ca1,500 stone artifacts, mainly flakes and debris, are made of local, high quality flint. Handaxes arelacking as well as the evidence for Levallois technology. Intensely retouched scrapers, as well asdenticulates, notched pieces and points on thick flakes, are most abundant[20].

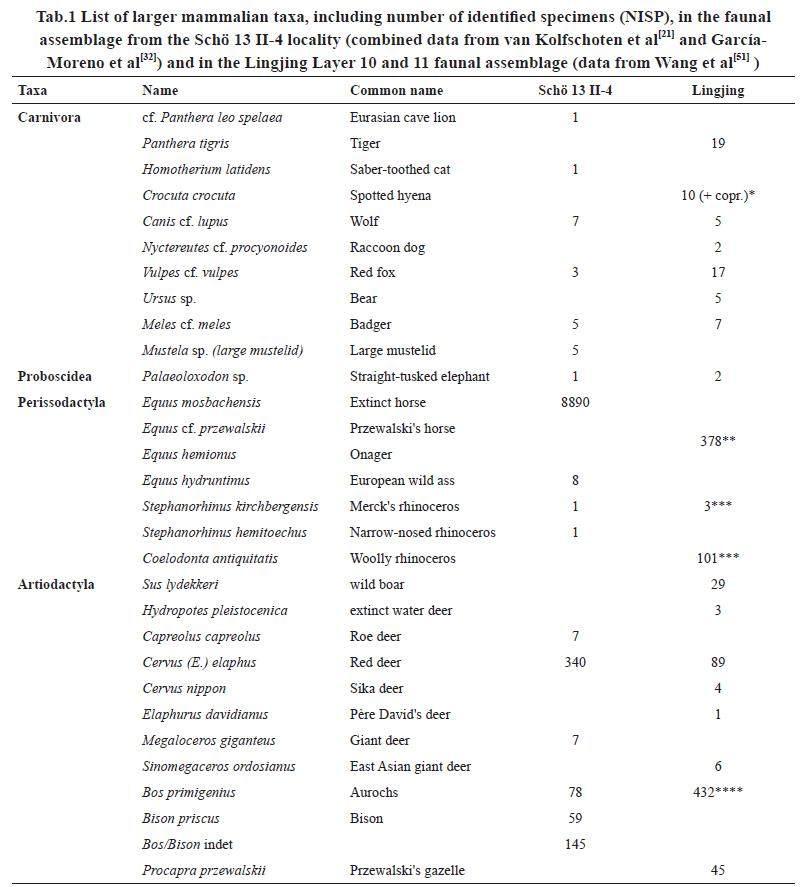

The larger mammal vertebrate record is extensive and very diverse[21] (Tab.1). The fossilcarnivore guild of the ‘Spear Horizon faunal assemblage includes saber-toothed cat, fox, andwolf. Herbivores are represented by one elephant species, two equid species, two rhinocerosspecies, two cervid species, and two large bovid species. The excavated archaeologicalassemblage from Sch? 13 II-4 is, with roughly 15,000 bones and bone fragments[21,22], is largelydominated by the Middle Pleistocene horse (Equus mosbachensis). Remains of other species suchas aurochs (Bos primigenius), bison (Bison priscus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus) are commonbut significantly less frequent.

Apart from the archaeological finds excavated at the Sch? 13 II-4 site, a huge amount of fossilpalaeobotanical (macro) remains[23,24], molluscs[25], insects, pisces, reptiles, amphibians[26], birds[11,21]and small mammal remains[27] have been collected from the excavated sediments. The extensivefossil record, combined with the carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios in the fossil remains ofdifferent herbivore species indicates that the environment, during hominin occupation of the Sch?13 II-4 site, consisted of a mosaic landscape with a mixture of forested areas and open grasslands[28].

The majority of the Sch? 13 II-4 vertebrate remains is very well preserved, not onlyat a macroscopic level but also at a molecular level; 47 of the 50 investigated bone samplesyielded good quality collagen[28]. The explanation for the excellent conservation is that, untilvery recently, the groundwater table was above the find horizon and the finds were located inanaerobic, waterlogged sediments The groundwater that originates from springs located at theneighbouring foothills of the Harz Mountains was, in addition, rich in calcium carbonate[29].

The Sch? 13 II-4 site is located at the edge of a former lake[13,16]. Most of archaeological findsare concentrated (with up to 150 specimens per square metre) in a north-south oriented, 10 m widestrip which runs parallel to the former lake shore. No habitation structures and no hearts have beenencountered[20]. Detailed taphonomical investigations indicate that most of the archaeological findswere recovered in primary position. There is no evidence for high-energy taphonomic and postdepositionalprocesses that would have had an impact on the spatial distribution of the assemblage[30].

The origin of the ‘Spear Horizon archaeological assemblage is regarded as natural as wellas the result of hominin hunting and butchering activities; the assemblage is composed of overtwenty almost complete horses, among others, butchered by hominins[20]. However, the assumptionis that not all the finds have been accumulated by hominins; for example, bones that displaymore intense signs of weathering are regarded to represent the natural background fauna[21].

2.1 Hominin interference

large number of larger mammal finds, horse bones in particular, show well-preserved featuresthat indicate hominin interference[10,11,21,31]. One group of artificial marks on the bones are related tobutchering activities such as skinning, defleshing and marrow extraction. A second group of artificialinduced features are visible on bones that are used as knapping tools and/or as bone hammer[10].

2.2 Butchering

The Sch? 13 II-4 site has yielded ca 25 more or less complete horse carcasses as well asisolated remnants of ca 25 additional individuals[21]. Detailed investigation of the horse bones[21,31]indicated that skinning of the carcasses was one of the major butchering activities and most of thehorse carcasses have also been taken apart. Numerous short marks that resulted from cutting jointligaments during the process of dismembering or disarticulation, are observed on the mandible,atlas, axis, scapula and on the postcranial long bones (humerus, ulna-radius, metacarpus, pelvis,femur, tibia, tarsal bones, and metatarsus)[21]. By far most of the encountered butchery traceson the horse remains point to defleshing or to filleting. The marrow-bearing skeletal elementsin particular (humerus, radius, femur and tibia) show a high percentage of filleting/defleshingmarks[31]. The high degree of fragmentation of the long bones, combined with the large numberof impact notches, indicate intensive marrow procurement. A large number of bone fragmentsexhibit conchoidal flake scars and some bones show impact depressions of the cortical surface.Impact notches are also visible along the lower rim of several horse mandibles. Breakage of themandible, most probably to gain access to the marrow located in the ventral part of the mandible,resulted, in some cases, in a horizontal breakage of the (pre)molars[21].

2.3 Bone tools - Retouchers

During the archaeozoological analyses of the larger mammal fossil assemblage from the site Sch?13 II-4, an extraordinary assemblage of 143 bone tools, bones and bone fragments used as percussors toretouch flint tools, have been encountered[10,32]. The bone tools show traces, e.g. pits and scores, producedduring the use of the bones to knap lithic tools. A notable feature of the knapping percussors from Sch?ningenis the relatively high incidence of knapping areas with flint chips embedded in the surface of the bone.

Of particular interest is the presence of scrape marks that invariably accompany knappingdamage found on retouchers made on both dry and fresh bones. Scraping was carried out before thetool was used for knapping, which suggests that the scraping was undertaken to prepare the bonesfor use as knapping tools by removing adhering soft tissue (such as periosteum) from the surfaceof the bone. By removing the ‘elastic periosteum the percussive properties of the knapping areaare modified and a harder surface suitable for efficient knapping is created[10]. The scraped surfacesare characterised by well-defined bands of parallel superficial striations, which are usually orientedparallel to the long axis of the bone. These marks are produced by a longitudinal scraping action whenthe edge of a stone tool is dragged or pushed across the bone surface. Some of the scrape marks areexceptionally long (Fig.2).

Horse carcasses providedthe main source of knappingtools and in addition, bones fromother taxa (sabre-toothed cat,red deer, large bovids) (Fig.3)appear to have been selectedfrom the background scatterof bones that might have beenbrought to the site from otherlocations. Of particular interestin this respect, is the presenceof knapping tools made on ‘drybones (possibly from naturaldeaths), some of which showsigns indicating that these boneshad been gnawed by carnivoresand weathered before they wereused as knapping tools. Themajority of the knapping toolswere made on fresh bones andthis group includes exampleswith cut marks indicating that they were procured during butchery. Detailed examination of the breakage patterns of thesebones indicates that many (if not all) of them were complete when used as knapping tool andbroken to extract marrow after they had been used as percussors[10]. This is in clear contrast toMousterian knapping techniques, as diaphysis splinters were preferentially used as retouchers[e.g. 33].

2.4 Bone tools - Bone hammers

The Sch?ningen Lower Palaeolithic record is unique because of the occurrence of theso-called ‘metapodial hammers qualified as such and presented by Van Kolfschoten et al[10].Fourteen horse metapodials and one bovid metacarpal with flaked and battered epiphyseshave been identified from the Sch?ningen 13 II-4 record. The crushing, chipping and flakingdamage are mainly concentrated on the medial and/or lateral margins of the distal condyles ofthe metapodia[10,22,31]. Five of the 14 horse metapodials and the bovid metacarpal bone show, inaddition, clear knapping marks. It shows that the tools are used for multiple tasks, an unparalleledphenomenon in the Eurasian Lower Palaeolithic record[10].

For a detailed description of the ‘Spear Horizon knapping tools and bone hammers, thereader is referred to van Kolfschoten et al(Fig.4)[10].

The archaeological record, encountered at the Sch? 13 II-4/‘Spear Horizon site indicatesthe presence of Lower Palaeolithic hominins on the shore of a lake and the elaborate exploitationof the Middle Pleistocene fauna. Hominins hunted and butchered several horse carcasses usingflint tools. Knapping bone tools were used to curate the flint tools and bones hammers were usedto smash in particular the long bones to get access to the bone marrow.

3 Lingjing in China

The Chinese site Xuchang-Lingjing is located in Henan Province (34o04'N, 113o41'E) at thesouthern edge of the North China Plain, between the eastern foot of the Songshan Mountains andthe Huang-Huai Plain, about 120 km south of the Yellow River (Fig.5)[34]. The open-air site wasdiscovered in 1965, when microblades and microcores, as well as mammalian fossils were collectedon the surface[35]. In 2005, researchers from the Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics andArchaeology started to excavate the site and during 2005 to 2017, over 550 m2 were excavated,most of the area to a depth of ca 9 m. Eleven geological strata have been identified (Fig.5) (Li et al,2017a) and three archaeological horizons were discovered. Layers 1-4 yielded cultural materials representing the Neolithic to the Shang-Zhou Bronze Age. Layer 5, dated to ca 13,500±406 BP,contains microblade technology, microcores, bone artifacts, perforated ostrich eggshells, ochre, faunalremains, and the first evidence of pottery appearing in the region[36,37]. Layer 5 yielded, in addition,a Palaeolithic bird figurine, an exceptionally well-preserved miniature carving of a standing bird[38].Layers 6-9 are sterile; they do not yield stone artifacts nor bone material. Layers 10 and 11 with anOptical Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) age of between 96±6 kaBP and 102±2 kaBP (Layer 10),respectively and between 105 kaBP and 125 kaBP (Layer 11)[39], yielded Middle Palaeolithic lithicartifacts and fossils animal remains.

A relatively small number of lithic artifacts, animal bones and small pebbles are fromthe base of layer 10. The largest archaeological assemblage, with more than 50,000 (lithicand archaeozoological) finds, originate from Layer 11. The lithic assemblage, with > 15,400artifacts, includes cores, flakes, and tools (i.e., scrapers, notches, denticulates, borers, points,choppers, etc.) predominately (>99%) made of quartz and quartzite dominate; chert is with<1% only marginally represented[40,41]. The lithic assemblages shows characteristics (e.g. thediscoidal core preparation) that allows the attribution to the Chinese Middle Palaeolithic[40,42,43].The abundance of debitage flakes and evidence for use wear on lithic artifacts suggests that themanufacture, use, re-sharpening and discard of lithic tools occurred at the site[40,43,44].

Among the most spectacular finds from Lingjing Layer 11 are the two fragmented, incompletehuman skulls (Xuchang 1 and Xuchang 2) excavated in situ in 2007 and 2014. The Xuchang Manskulls derive from young adults; they are considered as eastern Eurasian late archaic homininsbecause of their low and broad neurocrania with the inferior maximum breadth[34,45]. Taking intoaccount the stratigraphical age of the skulls as well as the geographical position of the site, theymight be attributed to Denisovan skulls as suggested by Martinón-Torres et al[46]. This propositionneeds to be confirmed by the results of further studies.

The more than 40,000 faunal remains from the lower part of Level 10 and from Level 11represent a variety of mammalian species[47,48,49,50,51](Tab.1). The carnivore guild from Lingjingincludes 7 different species, diverse and includes larger carnivores such as a bear Ursus sp.,a tiger Panthera cf. tigris and a hyena Crocuta cf. crocuta. Herbivores dominate the faunalassemblage; the aurochs Bos primigenius is by far the best-represented species. Dental aswell as postcranial remains of the equids Equus cf. przewalskii and Equus hemionus are alsoabundant. Other taxa, e.g. the woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis, the suid Sus lydekkeri,the red deer Cervus (E.) elaphus and the gazelle Procapra przewalskii, are well representedbut less abundant(Tab.1). The Lingjing fauna indicates a grassland-dominated palaeoecologicalenvironment, with a mosaic of scattered forest and mixed forest vegetation[47].

The faunal remains excavated from Layers 10 and 11 show a high degree of fragmentation.The 2017 Lingjing excavation of Layers 10 and 11 yielded respectively 976 and 1260 finds: 85 %of the finds from Layer 10 and 70% of the finds from Layer 11 are less than 5 cm long[43]. Manybone elements are heavily affected by weathering: Layer 10, 58.6% of the finds; Layer 11, 29.0% of the excavated elements. Concretion deposits are present on 51.2% of the finds from Layer 10and on 67.9% of the finds from Layer 11. Additional natural modifications include manganesestaining and root-etching. Modifications by carnivores are with <1% very rare[43].

The site Lingjing is an open-air site that is located within a lowland depression, at the edgeof a shore of a former pool, presumably fed from a nearby spring[34]. There are no indicationsof habitation structures or hearts. Zhang et al[52,53] concluded, based on the analyses of the 2005and 2006 record, that the Lingjing site was a kill-butchery site rather than a home base for earlyhumans. The taphonomic and zooarchaeological characteristics of the animal remains, i.e. speciesrichness, mortality patterns, skeletal element profiles and bone surface-modifications support thisconclusion. The authors also concluded that the natural component in the accumulation of thefaunal material is, most probably, very limited.

Based on a variety of sedimentary and archaeological indicators, Li et al[54] concluded thatthe disturbance is limited and the assemblage integrity at the Lingjing site is high, which impliesthat human behavioural information is well preserved. They also concluded that the uninterruptedvertical distribution (up to >1 m) of the remains throughout the Layer 10 and 11 sequence, alongwith the large number of faunal remains representing different taxa, demonstrates that the sitewas occupied by humans repeatedly over a relatively long period[54].

3.1 Hominin interference

It is obvious that hominins played an important role in the accumulation of the Lingjingfaunal assemblage from both Layer 11 and the base of Layer 10. The mortality profiles of the twodominant prey species, i.e., the Onager Equus hemionus and the Aurochs Bos primigenius, showa domination of prime-adult individuals[48,50,52,53]. This feature demonstrates the focussed huntingstrategy of Xuchang Man. However, a natural component in the accumulation of the assemblageshould not be excluded. The woolly rhinoceros assemblage is, for example, dominated by youngindividuals, which suggests a natural accumulation.

Cut marks are abundant in particular on the upper and lower limb bones. Zhang et al[52]investigated the hominin modification of the >10,000 faunal remains from an area of ca 300 m2,excavated in 2005 and 2006, and discovered that ca 13% of the finds show cutmarks, predominantly(98.5%) on the midshafts of long bones[52,53]. The morphological characteristics of the marks aswell as their location and orientation, indicate disarticulation and meat exploitation. Scraping marksare very rare which, according to Zhang et al[52], indicates a non-intensive processing technique.

Lingjing, Layer 11 yielded, in addition, two bone fragments bearing each 10 and 13 subparallellines incised, with a sharp object, on weathered bone[55]. Residue analyses demonstratedthe presence of ochre within the incised lines on one specimen; a discovery that represents theoldest known ochred engravings for non-utilitarian, symbolic purposes in East Asia[55].

The number of complete bones in the Lingjing assemblage is very low. The vast majority ofthe bones are fragmented suggesting hominin exploitation of marrow. The breakage pattern shows that we are dealing with green- as well as dry-bone fractures. However, it is well-known thathyaenas, represented in the associated fauna, also have the capacity to break bones. Future analysesshould clarify the role of the large carnivores in the fragmentation of the Lingjing bone assemblage.

3.2 Bone tools

Three different type of bone tools have been encountered in the Lingjing Layer 10 and 11archaeological assemblage: retouchers, metapodial bone hammers and deliberately knapped longbonefragments.

3.2.1 Retouchers

So far, a few dozen bone retouchers have been encountered in the Lingjing Layer 10 and11 archaeological assemblage[56]; 10 specimens are described in detail by Doyon et al[42,43]. Themodification of the bone surface indicates that the bone fragments were used in passive andactive pressure flaking activities. The majority (85%) of the retouchers consists of fragments withfeatures that indicate a single retouching event to curate or sharpen stone tools. A second categoryof retouchers consists of intentionally modified, weathered, elongated fragments of cervidsmetapodials that show recurrent use. The fossil assemblage contains, in addition, an antlerfragment with impact scars as well as linear scores that indicate the use as soft hammer[42,43].

3.2.2 Bone hammers

An additional set of bone tools in the Lingjing Layer 10 and 11 assemblage are thebone hammers recovered. Numerous bones/bone fragments show modification features thatare regarded as battering damage indicating that the bones were used as bone hammers. Theencountered crushing, chipping and flaking damage is located on, and so far restricted to, themedial and/or lateral margins of the distal condyles of metapodials of large herbivores (equids,cervids and bovids). The most severe form of damage of the metapodial hammers are diaphysealand/or distal fractures. All the distal epiphyses and the diaphyses of the metacarpal and metatarsalbones identified as being used as hammer, are fused which indicates that only bones of adultindividuals are used. The Lingjing bone hammers are still under investigation; therefore, onlypreliminary results are presented in this paper.

About half of the 40 equid metapodials show modifications that are the result of hammeringactivities. The distal metacarpal as well as metatarsal bones of both equid species (Equus cf. przewalskiiand Equus hemionus) show damages that ranges from incipient crushing damage at the lateral and/ormedial side and the medial ridge to the absence of big flakes and major crushing and chipping damageat the lateral and medial edges of the epiphyse (Fig.6). The only two complete metatarsals, both assignedto E. hemionus, do not show any damage that could be related to the use of the bone as hammer.

Only two metapodial bones in the Lingjing Layer 10 and 11 fossil assemblage, assigned to alarge cervid, show damages that is the result of hammering activities. The features are identical to thoseencountered at the bovid metapodial bones/bone fragments assigned to the aurochs Bos primigenius.The number of aurochs metapodials is with more than 150 specimens very large and based on the largevariation is size, it is concluded that both aurochs males and females are represented in the assemblage.

The aurochs bone hammer assemblage shows a variety of battering damage ranging fromno obvious damage, incipient damage, minor damage to major damage. Major damage, apartfrom crushing, includes chipping and flaking damage, transverse breaks just above the distalepiphyses (Fig.7). Fractures that often results in the absence of one, or in a number of specimens,both distal epiphyses. This explains the large number (ca 70) of isolated epicondyles; many ofwhich show crushing and chipping damage.

3.2.3 Long bone fragments

Doyon et al[56] describe the occurrence of 56 long bone fragments with more than six,intentional removed, flake scares that are arranged contiguously or in interspersed series.Experiments showed that fragmentation of long bones to exploit the marrow seldom results inbone fragments with a high number of flake scares. It is therefore concluded by the authors thatthe bone fragments were deliberately knapped to be used as tools.

4 Sch?ningen and Lingjing compared

Sch?ningen and Lingjing are both localities with a succession of strata and multiplearchaeological horizons; the oldest horizon at Sch?ningen is late Lower Palaeolithic in age, theoldest at Lingjing are Middle Palaeolithic in age. The Lower Palaeolithic Sch?ningen depositsconsist of organic-rich silt and fine-grained sand, peat and gyttja[13] and the Sch? 13 II-4 site,presented above, is from a bed that is very rich in organic silt and plant remains. The MiddlePalaeolithic Lingjing sequence consists of greyish green silt at the base (Layer 11) with on topgreyish yellow silt (Layer 10); the organic component in both lacustrine deposits is very low.

The Sch? 13 II-4 site is rich in botanical remains and it yielded numerous wooden artifacts,a category that has not been encountered at Lingjing. Both sites also differ in the occurrence offossil molluscs and small vertebrates. The Sch?ningen deposits are extremely rich in remains ofthese two categories whereas molluscs are missing from the Lingjing deposits and the number ofsmall vertebrates is very low. Another important difference between the sites is the presence ofhominin remains in the archaeological assemblage. The site Lingjing yielded skull fragments oftwo hominin; the site Sch? 13 II-4, did not yield so far, despite of the detailed investigation of theseveral thousand fossil remains, a single fragment that could be assigned to a hominin.

However, the Sch?ningen 13 II-4 and Lingjing Layer 10 and 11 also show severalsimilarities:

1) both localities are open-air sites.

2) they are located at the edge of a lake or a pool.

3) they occur in a mosaic landscape with a mixture of forested areas and open grasslands.

4) the large mammal fauna from both sites is very diverse.

5) the very large amount of well-preserved finds.

6) preserved under an-aerobe conditions.

7) in calcium-carbonate-rich groundwater that originated from a nearby spring.

8) both sites are kill-butchery sites.

9) both include stone tools as well as bone tools (retouchers and bone hammers).

The most striking similarity, from an archaeological point of view, is the presence of bone tools,and in particular the presence of bone hammers that have several characteristic features in common.

5 Discussion and conclusion

Part of the similarities listed above have almost certainly, arise from natural conditions. Thepresence of open water made both sites, Sch? 13 II-4 and Lingjing Layer 10 and 11, attractivefor hominins as well as animals. The palaeo-environmental proxies determined indicate thatthe natural conditions during the time of hominin occupation at both sites are rather similarand the location of both sites in a mosaic palaeo-landscape explains the presence of a diverselarger mammal fauna, comparable in composition. It is unambiguous whether the calciumcarbonate-rich groundwater, originated from a spring in the vicinity, played an important rolein the preservation of the fossil material at both sites. This is especially true for the Sch?ningenfinds that are embedded in deposits rich in organic silt and plant remains; normally not the bestenvironment for the preservation of skeletal materials.

The hominin activities at both sites are apparently also rather similar. Both sites have beenclassified as kill-butchery sites. The fossil record at both sites show an overrepresentation ofspecific species. For the Sch? 13 II-4, the horse Equus mosbachensis, is by far the dominantanimal whereas in the Lingjing Layer 10 and 11 assemblage the Aurochs Bos primigenius andthe Onager Equus hemionus, almost exclusively represented by prime-adult individuals, are bestrepresented. It clearly shows that hominins played a significant role in the accumulation of thefossil assemblage. However, at both sites there is almost certainly also a natural component in theaccumulation that explains the occurrence of isolated remains of a variety of other species.

The accumulated carcasses at both sites, show a large number of cut marks, in particularon the upper and lower limb bones; features that indicate hominin butchering activities(disarticulation and meat exploitation). The fragmented nature of the bone assemblages fromboth sites underlines the importance of marrow exploitation in hominin subsistence.

Stone tools play an important role in the butchering activities. The Sch? 13 II-4 stone toolswere made of flint whereas the Lingjing Layers 10 and 11 stone tools were predominantly made ofquartz and quartzite. Bone retouchers, used to curate the stone tools, are present in the assemblagesof both sites. However, the bone retouchers from both sites differ in the occurrence of clear longscrape marks. The Sch? 13 II-4 record includes many knapping tools with scraped surfaces and it isobvious that scraping was carried out before the tool was used as retoucher. These results highlightthe advanced knowledge in the use of bones as tools during the Lower Palaeolithic[10]. Bones withidentical features have, so far, not been encountered in the Lingjing Layers 10 and 11 assemblage.

The discovery of a number of metapodial bones with modifications that indicated theirpossible use as bone hammers, in the Sch? 13 II-4 assemblage was rather spectacular. In line withethnographic observations by Binford[57], who described how the Nunamiut use reindeer metapodiato fracture other limb bones for their bone marrow, van Kolfschoten et al[10] hypothesised that thebattered metapodia from Sch?ningen were used to break both limb bones and mandibles instead of knapping percussors to curate stone artifacts, as suggested by Voormolen[31]. Experimentswith fresh horse bones verified that horse metapodia were effective tools for breaking open otherlimb bones and that the metapodia sustained the characteristic battering damage that is observedin the fossil record of Sch?ningen[22,58]. Sch?ningen was until recently, the only site that hadyielded clear examples of Palaeolithic bone hammers. Detailed analyses of the Lingjing MiddlePalaeolithic assemblage, however, resulted in a second site with a large number of bone hammers.These bone hammer assemblages from both sites have in common that bones of different speciesare represented. However, the Sch? 13 II-4 bone hammer assemblage is dominated by horsemetapodials whereas large bovid metapodial form the majority in the Lingjing assemblage. Thebone modification features, visible at the bone hammers from both sites, are extremely similarindicating strong similarities in the use of the bone tools. It is assumed that the bone hammerswere used at both sites to smash other bones in order to get access to the bone marrow.

It is obvious that we are looking at two important sites, one in Europe and one in Asia, bothwith an unique record of bone hammers. However, despite the fact that both sites show many(unique) similarities, we cannot assume a (cultural) link between the hominin populations activeat both localities. This is because of the geographical distance between the two sites of > 8,000km and even more important, a difference in age of ca 200 kaBP. We assume that the observedsimilarities have partly a natural basis, and are partly the result of opportunistic homininbehaviour. Aspects that should be excluded when cultural links are assumed.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of ActaAnthropologica Sinica John W. Olson for the invitation to submit a manuscript to be includedin an upcoming Special Issue entitled “Pleistocene Human Migrations and Dispersals.” We alsowould like to thank Phil L. Gibbard for the linguistic improvements of the text.

Reference

[1] Iakovleva L. The architecture of mammoth bone circular dwellings of the Upper Palaeolithic settlements in Central and Eastern Europe and their socio-symbolic meanings. Quaternary International, 2015, 359-360: 324-334

[2] Kuhn SL, Stiner MC.Hearth and home in the Middle Pleistocene. J. Anthropol. Res., 2019, 75: 305-327-

[3] Stiner MC. Honor Among Thieves: A Zooarchaeological Study of Neandertal Ecology. Princeton: NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994

[4] Bunn HT, Gurtov AN. Prey mortality profiles indicate that Early Pleistocene Homo at Olduvai was an ambush predator. Quaternary International, 2013, 322-323: 44-53

[5] Stringer C, Andrews P. The Complete World of Human Evolution. London: Thames & Hudson, 2005

[6] Hutson JM, Villaluenga A, García-Moreno A, et al. On the use of metapodials as tools at Sch?ningen 13II-4. In: Hutson JM, García Moreno A, Noack ES, et al.(eds.). The Origins of Bone Tool Technologies: “Retouching the Palaeolithic: Becoming Human and the Origins of Bone Tool Technology”. Mainz: RGZM, 2018

[7] Harmand S, Lewis J, Feibel C, et al. 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature, 2015, 521: 310-315

[8] Brain CK, Shipman P. Swartkrans chapter - The Swartkrans Bone Tools. In: Brain CK ed. Swartkrans. A Caves Chronicle of Early Man. Pretoria: Transvaal Mus Monograph, 1993, 8: 195-221

[9] Backwell LR, DErrico F. Early hominid bone tools from Drimolen, South Africa. Journal of Archaeological Sciences, 2008, 35: 2880-2894

[10] van Kolfschoten T, Parfitt SA, Serangeli J, et al. Lower Paleolithic bone tools from the "Spear Horizon" at Sch?ningen (Germany).Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 226-263

[11] Hutson JM, Villaluenga A, García-Moreno A, et al. A zooarchaeological and taphonomic perspective of hominin behaviour from the Sch?ningen 13 II-4 “Spear Horizon”. In: García-Moreno A, Hutson JM, Smith GM, et al.(eds.). Human behavioural adaptations to interglacial lakeshore environments. Mainz: RGZM, 2020: 43-66

[12] Lang J, Winsemann J, Steinmetz D, et al. The Pleistocene of Sch?ningen, Germany: a complex tunnel valley fill revealed from 3D subsurface modelling and shear wave seismics. Quaternary Science Review, 2012, 39: 1-20

[13] Lang J, B?hner U, Polom U. The Middle Pleistocene tunnel valley at Sch?ningen as a Paleolithic archive. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 18-26

[14] Serangeli J, B?hner U, van Kolfschoten T, et al. Overview and new results from large-scale excavations in Sch?ningen. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 27-45

[15] Richter D, Krbetschek M. The age of the Lower Palaeolithic occupation at Sch?ningen. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 46-56

[16] Tucci M, Krahn KJ, Richter D, et al. Evidence for the age and timing of environmental change associated with a Lower Palaeolithic site within the Middle Pleistocene Reinsdorf sequence of the Sch?ningen coal mine, Germany. Palaeogeography,Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2021, 569, 110309

[17] Thieme H. Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany. Nature, 1997, 385: 807-810

[18] Conard NJ, Serangeli J, Bigga G, et al. A 300,000-year-old throwing stick from Sch?ningen, northern Germany, documents the evolution of human hunting. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2020, 4: 690-693

[19] Schoch WH, Bigga G, B?hner U, et al. New insights on the wooden weapons from the Paleolithic site of Sch?ningen. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 214-225

[20] Serangeli J, Rodríguez-?lvarez B, Tucci M, et al. The Project Sch?ningen from an ecological and cultural perspective. Quaternary Science Review, 2018, 198: 140-155

[21] van Kolfschoten T, Buhrs E, Verheijen I. The larger mammal fauna from the Lower Paleolithic Sch?ningen Spear site and its contribution to hominin subsistence. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 138-153

[22] Hutson JM, García-Moreno A, Noack ES, et al. The origins of bone tool technologies: an introduction. In: Hutson JM, García Moreno A, Noack ES, et al.(eds.). The Origins of Bone Tool Technologies: “Retouching the Palaeolithic: Becoming Human and the Origins of Bone Tool Technology”. Mainz: RGZM, 2018: 53-91

[23] Urban B, Sierralta M, Frechen, M. New evidence for vegetation development and timing of Upper Middle Pleistocene interglacials in Northern Germany and tentative correlations. Quaternary International, 2011, 241: 125-142

[24] Bigga G, Schoch WH, Urban B. Paleoenvironment and possibilities of plant exploitation in the Middle Pleistocene of Sch?ningen(Germany). Insights from botanical macro-remains and pollen. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 92-104

[25] Mania D. Die fossilen Weichtiere (Mollusken) aus den Beckensedimenten des Zyklus Sch?ningen II (Reinsdorf-Warmzeit). In:Thieme H (ed.). Die Sch?ninger Speere - Mensch und Jagd vor 400.000 Jahren. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 2007: 99-104

[26] B?hme G. Fische, amphibien und reptilien aus dem Mittelpleistoz?an (Reinsdorf-Interglazial) von Sch?ningen (II) bei Helmstedt (Niedersachsen).In: Terberger T, Winghart S(eds.). Die Geologie der pal?olithischen Fundstellen von Sch?ningen. Mainz: RGZM, 2015. 203-265

[27] van Kolfschoten T. The Palaeolithic locality Sch?ningen (Germany): A review of the mammalian record. Quaternary International,2014, 326-327: 469-480

[28] Kuitems M, van der Plicht J, Drucker DG, et al. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes of well-preserved Middle Pleistocene bone collagen from Sch?ningen (Germany) and their paleoecological implications. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 105-113

[29] Serangeli J, Bigga G, B?hner U, et al. Ein Fenster ins Altpal?olithikum. Arch?ologie in Deutschland, 2012, 4: 6-12

[30] Peters CAE, van Kolfschoten T, 2020. The site formation history of Sch?ningen 13II-4 (Germany): Testing different models of site formation by means of spatial analysis, spatial statistics and orientation analysis. Journal of Archaeological Sciences, 2020, 114: 105067

[31] Voormolen B. Ancient hunters, modern butchers: Scho?ningen 13 II-4, a kill-butchery site dating from the northwest European Lower Palaeolithic. Dissertation Leiden University, 2008: 1-145

[32] García-Moreno A, Hutson J M, Villaluenga A, et al. A detailed analysis of the spatial distribution of Sch?ningen 13II-4 ‘Spear Horizon remains. Journal of Human Evolution, 2021, 152: 102947

[33] Abrams G, Bello SM, Di Modica K, et al. When Neanderthals used cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) remains: Bone retouchers from unit 5 of Scladina Cave (Belgium). Quaternary International, 2014, 326-327: 274-287

[34] Li Z, Wu X, Zhou L, et al. Late Pleistocene archaic human crania from Xuchang, China. Science, 2017, 355: 969-972

[35] Zhou GX. Stone age remains from Lingjing, Xuchang of Henan province. Kaogu, 1974, 2: 91-108

[36] Li Z, Ma H. Techno-typological analysis of the microlithic assemblage at the Xuchang Man site, Lingjing, central China.Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 120-129

[37] Li Z, Kunikita D, Kato S. Early pottery from the Lingjing site and the emergence of pottery in northern China. Quaternary International, 2017, 441: 49-61

[38] Li Z, Doyon L, Fang H, et al. A Paleolithic bird figurine from the Lingjing site, Henan, China. PLoS ONE, 2020, 15(6): e0233370

[39] Nian XM, Zhou LP, Qin JT. Comparisons of equivalent dose values obtained with different protocols using a lacustrine sediment sample from Xuchang, China. Radiat Meas, 2009, 44: 512-516

[40] Li H, Li Z, Gao X, et al. Technological behavior of the early Late Pleistocene archaic humans at Lingjing (Xuchang, China).Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2019, 11: 3477-3490

[41] Zhao, Q, Ma H, Bae C J. New discoveries from the early Late Pleistocene Lingjing site (Xuchang). Quaternary International, 2020, 563: 87-95

[42] Doyon L, Li Z, Li H, et al. Discovery of circa 115,000-year-old bone retouchers at Lingjing, Henan, China. PLoS ONE, 2018, 13: e0194318

[43] Doyon L, Li H, Li Z, et al.. Further evidence of organic soft hammer percussion and pressure retouch from Lingjing (Xuchang,Henan, China). Lithic Technology, 2019, 44: 100-117

[44] Li Z. A primary study on the stone artifacts of Lingjing site excavated in 2005. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2007, 26: 138-154

[45] Trinkhaus E, Wu X-J. External auditory exostoses in the Xuchang and Xujiayao human remains: Patterns and implications among eastern Eurasian Middle and Late Pleistocene crania. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12: e0189390

[46] Martinón-Torres M, Wu X, Bermúdez de Castro JM, et al. Homo sapiens in the Eastern Asian Late Pleistocene. Current Anthropology, 2017, 58: 434-448

[47] Li Z, Dong W. Mammalian fauna from the Lingjing Paleolithic site in Xuchang, Henan Province. Acta Anthropologica Sinica,2007, 26: 345-360

[48] Zhang SQ. Taphonomic study of the faunal remains from the Lingjing Site, Xuchang, Henan Province (in Chinese). Dissertation Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2009: 1-216

[49] Wang W, Li Z, Song G, et al. A study of possible hyaena coprolites from the Lingjing site, Central China. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2015, 34: 117-125

[50] van Kolfschoten T, Li Z, Wang H, et al. The Middle Palaeolithic site of Lingjing (Xuchang, Henan, China): Preliminary new results. In: Klinkenberg V, van Oosten R, van Driel-Murray C(eds.). A Human Environment Studies in honour of 20 years Analecta editorship by prof dr Corrie Bakels. Analecta Praehistoria Leidensia, 2020, 50: 21-28

[51] Wang H, Li Z, Tong H, et al. Hominin paleoenvironment in East Asia: The Middle Paleolithic Xuchang-Lingjing (China)mammalian evidence. Quaternary International, 2021: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.11.024

[52] Zhang S, Li Z, Zhang Y, et al. Cultural Modifications on the Animal Bones from the Lingjing Site, Henan Province. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2011, 30: 313-326

[53] Zhang S, Gao X, Zhang Y, et al. Taphonomic analysis of the Lingjing fauna and the first report of a Middle Paleolithic kill-butchery site in North China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2011, 56: 3213-3219

[54] Li H, Li Z, Lotter MG, et al. Formation processes at the early Late Pleistocene archaic human site of Lingjing, China. J Archaeol Sci, 2018, 96: 73-84

[55] Li Z, Doyon L, Li H, et al. Engraved bones from the archaic hominin site of Lingjing, Henan Province. Antiquity, 2019, 93: 886-900

[56] Doyon L, Li Z, Wang H, et al. A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China. PLoS ONE, 2021, 16(5): e0250156

[57] Binford LR. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology. New York, Academic press, 1978

[58] Bonhof WJ, van Kolfschoten T. The metapodial hammers from the Lower Palaeolithic site of Sch?ningen 13 II-4 (Germany): The results of experimental research. Journal of Archaeological Sciences: Reports, 2021, 35: 102685

[59] Stahlschmidt MC, Miller CE, Ligouis B, et al. On the evidence for human use and control of fire at Sch?ningen. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 89: 71-91

基金项目:国家社会科学基金一般项目(20BKG036)/Supported by National Social Science Funding(20BKG036)