多能干细胞治疗视网膜退行性疾病:从实验室到临床转化的现状与挑战

2024-03-24郭艳鲍莉纪猛吴月红

郭艳 鲍莉 纪猛 吴月红

摘要: 视网膜色素上皮细胞(Retinal pigment epithelial cells, RPE)是位于视网膜底部致密的细胞层,其损伤导致年龄相关性黄斑变性(Age-related macular degeneration, AMD)、Stargardt病(Stargardt macular dystrophy, STGD)和色素性视网膜炎(Retinitis pigmentosa, RP)等视网膜疾病,RPE移植已成为治疗RPE损伤性疾病的有效方案。来源于人多能干细胞(Human pluripotent stem cells, hPSC)的视网膜色素上皮细胞,具有与人原代RPE相似的功能和容易制备等优点,已成为RPE移植的最主要细胞来源之一。文章对hPSC-RPE治疗视网膜退行性疾病的临床试验进展进行了总结和归纳,并阐述了目前面临的挑战与风险。

关键词: 人多能干细胞;视网膜色素上皮细胞;年龄相关性黄斑变性;Stargardt病;色素性视网膜炎;细胞治疗

中图分类号: Q291

文献标志码: A

文章编号: 1673-3851 (2024) 01-0130-15

引文格式:郭艳,鲍莉,纪猛,等. 多能干细胞治疗视网膜退行性疾病:从实验室到临床转化的现状与挑战[J]. 浙江理工大学学报(自然科学),2024,51(1):130-144.

Reference Format: GUO Yan,BAO Li,JI Meng, et al. Pluripotent stem cells in the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases: Current situation and challenges from bench to bedside[J]. Journal of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University,2024,51(1):130-144.

Pluripotent stem cells in the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases: Current situation and challenges from bench to bedside

GUO Yan1,BAO Li1,JI Meng2,WU Yuehong1

(1.College of Life Science and Medicine, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou 310018, China;

2.Asia Stem Cell Therapeutics Co., Ltd., Hangzhou 310018, China)

Abstract: Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells are located in a dense layer of cells at the bottom of the retina, and their damage can result in age-related macular degeneration (AMD), Stargardt macular dystrophy (STGD), Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and other retinal degenerative diseases. RPE transplantation has become an effective treatment for such diseases at present. RPE cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSC), namely hPSC-RPE, have become the main source of RPE transplantation because of their similar function and easy preparation to human primary RPE. This article summarizes the clinical trials of hPSC-RPE in the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases, and expounds the challenges and risks we are facing at present.

Key words: human pluripotent stem cells; retinal pigment epithelium; age-related macular degeneration; stargardt macular dystrophy; retinitis pigmentosa; cell therapy

0引言

年齡相关性黄斑变性(Age-related macular degeneration, AMD)、色素性视网膜炎(Retinitis pigmentosa,RP)和Stargardt病(Stargardt macular dystrophy, STGD)[1-3]为常见的视网膜退行性疾病,是近些年导致失明的主要眼部疾病。AMD、RP和STGD是由视网膜感光细胞或视网膜色素上皮细胞(Retinal pigment epithelial cells, RPE)的退化和死亡引起[4],目前尚未有根治的方法。变性或死亡的RPE很难修复和再生[5];细胞治疗可以替代受损的RPE来恢复视觉功能,相关治疗方法已有大量报道[6-8]。人多能干细胞(Human pluripotent stem cells, hPSC)为细胞治疗提供新的细胞来源,目前的临床数据表明,来源于人多能干细胞的视网膜色素上皮细胞(Human pluripotent stem cells derived retinal pigment epithelial cells, hPSC-RPE)安全有效[6-8],但干细胞疗法仍面临很多风险与挑战。

本文对hPSC-RPE治疗视网膜退行性疾病的临床试验进展及目前面临的风险和挑战进行综述。概述视网膜退行性疾病的发生及目前的治疗方案,总结RPE细胞治疗的研究进展,归纳 hPSC-RPE治疗的现状以及面临的风险和挑战等。

1视网膜退行性疾病

RPE为致密的单层细胞,位于光感受器和脉络膜之间,呈“鹅卵石”形状,富含色素颗粒,对于支持光感受器细胞的营养、结构和代谢不可或缺[9]。RPE在维持视网膜功能方面具有重要作用,包括与感光细胞接触并为其提供营养、代谢废物的吞噬等,且参与构成血-视网膜屏障防止物质从脉络膜非特异性扩散等功能[10-11]。RPE细胞的损伤和缺失会引起继发性视网膜感光细胞耗竭,从而导致视网膜退行性病变[4]。

1.1年龄相关性黄斑变性

AMD又称为老年性黄斑变性,是欧美国家老年人群中引起失明的主要眼部疾病[12]。目前全球超过2.00亿人患AMD,预计在2040年将增加到2.88亿人,并且约有10%的人处于疾病晚期[13]。年龄是导致AMD发生的主要因素,在欧洲人群中85岁以上的患病率约为30%[14];吸烟和饮食等生活方式也是导致AMD发生的因素[15];基因突变也与AMD患病率的增加相关[16-18]。晚期AMD包括干性AMD和湿性AMD。干性AMD是由于Bruch膜上脂褐素的过度积累和慢性炎症导致RPE以及感光细胞氧化损伤以及退化,使得视力急剧下降甚至失明[19];湿性AMD是因为脉络膜血管过度增殖到视网膜中,导致视力急剧下降,严重时也会导致失明[20]。目前湿性AMD的治疗可以通过注射抗血管内皮生长因子(Vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF)衍生药物缓解视力衰退,在临床上常用治疗药物为雷珠单抗、贝伐单抗和阿柏西普等[21],但这些药物不能完全阻止视网膜内持续的血液和液体渗漏,从而导致慢性视网膜下间隙的纤维化,最终引起黄斑萎缩[22]。AMD患者中超过80%患有干性AMD,目前临床上还没有针对干性AMD的有效治疗方法,也未见获批的治疗药物。通过补体抑制、神经保护和抗炎因子等多种靶点来治疗AMD的研究已见报道,但均未获得较好的治疗效果[23-24]。

1.2Stargardt病

STGD是儿童和青少年常见的致盲性眼病,平均每8000~10000人中有1人患病[25]。STGD是一种常染色体隐性遗传病,由ABCA4突变引起[26-27]。ABCA4基因编码的ABCA4蛋白在视网膜感光细胞和视网膜色素上皮细胞中特异性表达,ABCA4的突变会导致有毒的N-视黄醛-N-视黄乙醇胺(A2E)在视网膜底部积聚,使得RPE萎缩和视网膜感光细胞死亡[28]。STGD患者通常经历快速的双眼中央视力丧失,并伴有视功能障碍和中央暗点。目前对于STGD的治疗策略是修复或替换ABCA4,基于腺病毒的基因替换治疗已经成功地应用于一些眼部疾病,但因ABCA4基因较大无法用腺病毒载体递送[28]。

1.3色素性视网膜炎

RP是一种罕见的遗传性视网膜退行性疾病,发病率约为1/4000,通常发生在青少年中[29]。RP通常是遗传类眼部疾病,包括X连锁隐性遗传(5%~15%)、常染色体显性遗传(30%~40%)和常染色体隐性遗传(40%~60%)。光转导级联、纤毛运输和纤毛结构的80多个基因的突变导致视网膜感光细胞的功能障碍和死亡,使得RPE细胞的功能紊乱和在视网膜内迁移,从而导致RR的发生[30]。RP患者多见于20~30岁,出现夜盲和进行性视野丧失,晚期为完全失明。治疗RP可通过对常染色体隐性和X连锁隐性RP患者的基因补充以及对常染色体显性RP患者进行基因组编辑,但该技术只能对黄斑没有明显光感受器丢失和已确定致病突变基因的患者有效[31-32]。

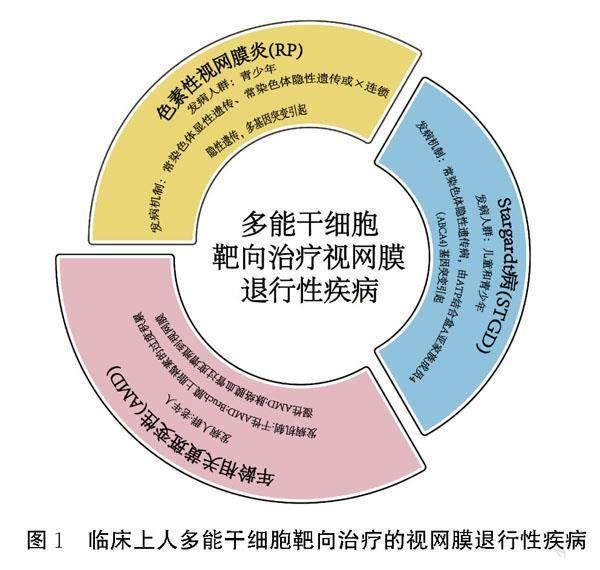

综上可知,AMD、RP和STGD均未获得有效治疗方案,细胞治疗可以替代受损的RPE。hPSC-RPE为细胞治疗提供了充足的细胞来源,目前hPSC-RPE治疗AMD、RP和STGD已进入临床试验阶段[33-35](见图1)。

2RPE细胞治疗研究进展

目前应用于细胞治疗的RPE来源主要为人自体或异体RPE、胎儿RPE和来源人多能干细胞的RPE(见表1)。1991年首次进行了人RPE临床移

植试验,第一位AMD患者在切除黄斑下的增生组织后进行了自体RPE细胞移植,移植后部分患者视力有所提高;第二位AMD患者进行同种异体RPE移植,但结果未显示对视力有所改善[36]。湿性AMD患者在脉络膜新生血管膜(Choroidal neovascularization, CNV)移除后移植人胎儿RPE细胞片层,术后患者发生了免疫排斥反应[37]。Weisz等[38]尝试将胎儿RPE细胞悬浮液注射在干性AMD患者视网膜底部,发现患者视力无明显改善,并且观察到移植区域有进行性视网膜下纤维化。Del Priore等[39]将湿性AMD患者的CNV膜摘除后移植了同种异体来源的RPE细胞,但视力并没有得到很好的改善。使用同种异体RPE移植的湿性AMD患者,由于CNV膜去除导致血-视网膜屏障受损,均表现出免疫排斥反應和视力下降;2012年首次公布了hPSC-RPE细胞的临床试验结果[40],证明了hPSC-RPE移植的安全性与可行性,随之hPSC-RPE移植在多个临床Ⅰ/Ⅱ期应用研究相继展开。

3hPSC-RPE

3.1hPSC

hPSC是可以无限增殖的具有分化能力的多能性细胞,分为人胚胎干细胞(Human embryonic stem cells, hESC)和人诱导多能干细胞(Human induced pluripotent stem cells, hiPSC)。1998年Thomson等[45]从人受精囊胚内的细胞团中分离并建立了hESC,发现hESC能够分化成所有类型的细胞和组织。2006年Takahashi等[46]通过逆转录病毒介导的转基因技术,将4个转录因子Oct3/4、Sox2、c-Myc及Klf4导入小鼠胚胎成纤维细胞(Mousee mbryonic fibroblast, MEF),获得了与hESC形态相似、分化能力相当的细胞,命名为诱导性多能干细胞。Takahashi等[47]和Yu等[48]进一步获得了来源于人成纤维细胞(Human fibroblast, HF)的hiPSC细胞。目前研究已证实,由hPSC诱导分化的视网膜细胞,包括RPE[49]、视网膜神经节细胞(Retinal ganglion cell, RGC)[50]和视网膜感光细胞[51],可为AMD、STGD和RP等视网膜疾病的治疗提供新的细胞来源。

3.2hPSC-RPE

2004年首次提出将hESC自发分化为RPE细胞[52],随后建立多种分化方案,并通过添加细胞因子和小分子化合物,如Nicotinamide、Activin A、CHIR99021、Noggin和SB431542等,来缩短分化时间和提高分化效率[53-55]。目前进入临床试验所用的分化方法有拟胚体和单层分化法两种,Hirami等[56]将hiPSC在含有Dkk-1 (100 ng/mL)和Lefty A (500 ng/mL)的无血清培养基进行拟胚体悬浮培养,第20天将拟胚体接种在涂有多聚D-赖氨酸、层粘连蛋白和纤维连接蛋白的载玻片上,第40天可见到典型的RPE形态;Lu等[57]利用hESC系MA01和MA09进行分化,在含有B-27补充剂的培养液中拟胚体悬浮培养7 d,接种在明胶包被的培养板中培养直到出现RPE;Liu等[58]利用Q-CTS-hESC-2细胞系单层自发向RPE分化,以上分化获得的RPE已进入人的临床试验[56-58],其他临床级别的分化方案已见报道 [59-60]。

3.3hPSC-RPE治疗视网膜退行性疾病

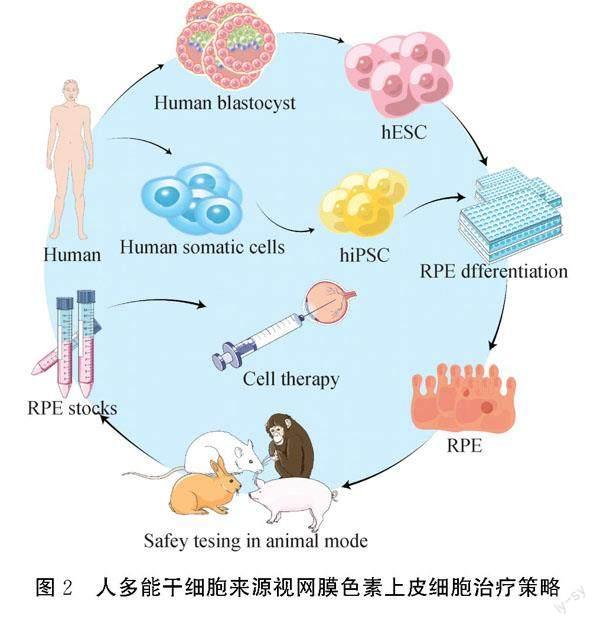

hPSC-RPE具有与人原代RPE细胞相似的功能,且比原代培养的RPE细胞更容易制备等优势,已成为视网膜退行性疾病细胞治疗的主要来源,hPSC-RPE治疗视网膜退行性疾病的策略(见图2)。已证实hPSC-RPE在视网膜下间隙发挥免疫调节作用:抑制T细胞激活,增加T细胞凋亡,并促进某些抗炎细胞因子的分泌[61]。hPSC-RPE细胞具有以下特点,更适合临床应用[34]:a)具有所需的功能;b)能够提供足够数量的移植细胞;c)可以达到临床级别质量认证和临床纯度标准。因此,多能干细胞,尤其是hPSC-RPE细胞,在眼科领域的临床应用中已显示出巨大潜力。

4hPSC-RPE的临床应用研究进展

4.1hESC-RPE的临床应用研究进展

2012年Schwartz等[40]公布了首个hESC-RPE临床试验结果,将hESC来源的RPE细胞产品MA09-hRPE移植到1名干性AMD患者(注册号:NCT01344993)和1名STGD患者(注册号:NCT01345006)的视网膜下腔,每只眼睛注射50000个细胞。在随后的4个月观察中两位患者未出现过度增殖、致瘤性、异位组织形成或明显排斥的现象,STGD患者的最佳矫正视力(Best-corrected visual acuity, BCVA)有所提高,干性AMD患者的视力也有所改善[40]。2015年Schwartz等[62]又对9名干性AMD患者(年龄>55岁)(注册号:NCT01344993)和9名STGD患者(年龄>18岁)(注册号:NCT01345006)进行了2项前瞻性的临床Ⅰ/Ⅱ期研究,将MA09-hRPE分别以50000、100000个和150000个细胞的剂量注射到患者的视网膜腔下进行22个月随访检查。在18名患者中,1名患者术后4 d出现了严重的玻璃体炎症,通过在玻璃体内注射抗生素、抗生素滴眼液和停用免疫抑制剂2个月后炎症消失;在观察期内所有患者均未发生不良增殖、注射部位移植组织生长畸胎瘤、异位组织或其他与hESC-RPE相关的明显眼部不良安全事件;患者也没有发生视网膜脱离、增殖性玻璃体视网膜病变或微血管阻塞;所有患者中10名患者BCVA提高,7名患者BCVA有微弱的提高或者保持不变,1名患者BCVA有所下降[62]。2018年Mehat等[63]针对hESC-RPE移植区域视网膜结构和功能检测开启了另一项临床Ⅰ/Ⅱ期试验(注册号:NCT01469832),将hESC-RPE悬液移植到12名晚期STGD病患者,全身免疫抑制治療13周,12名患者随访1年内均未出现移植不良反应,视力均保持稳定。AIRM有1项hESC-RPE临床试验被撤回,注册号为NCT02563782,原因是改变研究设计与细胞系;Ocata Therapeutics公司有1项临床试验被撤回,注册号为NCT02122159,原因是研究待修订、未来计划待定(https://clinicaltrials.gov/)。Song等[64]将hESC-RPE细胞悬液分别注射到2名干性AMD患者(注册号:NCT01674829)和2名Stargardt病患者(注册号:NCT01625559)的视网膜下,每只眼睛注射40000个细胞,随访1年未发现与移植细胞相关的严重安全问题例如不良增殖、致瘤性、异位组织形成等,患者在随访期间出现的其他身体问题经专家鉴定均与手术无关;3名患者BCVA提高,1名患者BCVA保持稳定,进一步证明了hESC来源的细胞可以作为一种潜在的安全的再生医学新的细胞来源。Youngje等[65]公布了针对3名Stargardt病患者的临床Ⅰ期试验结果(注册号:NCT01625559),将50000个hESC-RPE细胞悬液注射到患者眼中,随访3年未观察到任何严重的全身不良事件以及与hESC-RPE细胞相关的严重眼部不良事件,也未发现畸胎瘤形成等异常增生以及严重的眼部炎症或明显的免疫排斥症状;有1名患者术后19周发生了视网膜脱落,但经鉴定认为与hESC-RPE细胞移植无关,1名患者BCVA提高,而其他患者BCVA保持稳定。Liu等[58]报道hESC-RPE移植的临床研究(注册号:NCT02749734),3名湿性AMD患者先进行脉络膜新生血管切除,视网膜底部注射hESC-RPE悬液,术后9个月出现了白内障等不良反应事件;在术后12个月的随访期间没有观察到病变区域有任何新的渗出性新血管生成、血管渗漏或持续的局部视网膜炎症,视觉功能有所改善,实验数据为使用hESC-RPE细胞缓解早期湿性AMD的策略提供了支撑。为了确定移植细胞的长期存活能力和视觉功能的进一步发展变化,Li等[66]针对NCT02749734临床试验将hESC-RPE细胞治疗扩展到7名早期STGD患者,患者随访5年以评价hESC-RPE治疗的远期安全性和有效性,发现除1名患者术后出现短暂性高眼压外,其余患者均无全身性或局部不良反应,7只手术眼在移植后1至4个月均有短暂的视觉功能增加或稳定。

2018年Moorfields Eye HospitalMoorfields眼科医院公布了hESC-RPE贴片PF-05206388(注册号为:NCT01691261)植入2名急性湿性AMD和近期快速视力下降患者的安全性和可行性的临床Ⅰ期研究结果[67],该研究发生了3起严重的不良事件,包括用于免疫抑制的氟松龙植入物的缝合线暴露、视网膜脱离以及口服强的松龙后糖尿病的恶化,但与hESC-RPE贴片移植无关;移植后12个月,2名患者的BCVA均有15个字母以上的改善。随后该临床试验又招募10位患者,正在进行中(https://clinicaltrials.gov/)。2018年Regenerative Patch Technologiesg公布的一项Ⅰ/Ⅱa期临床研究结果显示:使用由在微聚苯乙烯膜上培养的单层hESC-RPE细胞组成的复合植入物CPCB-RPE1(注册号:NCT02590692)治疗5名年龄在69~85岁之间患有晚期干性AMD和GA的患者,其中,有4名患者接受了CPCB-RPE1的移植,1名患者因为术中视网膜下间隙中存在纤维蛋白碎片没有接受移植;对4名患者进行120~365 d随访,发现CPCB-RPE1的整体外观包括色素沉着、位置和大小没有变化,位置稳定未发生移位;所有患者均未出现与移植、手术或免疫抑制相关的意外严重不良事件,接受移植的患者视力均保持稳定,没有恶化,其中1名患者BCVA改善了17个字母[68]。2021年该团队又对16名患者进行移植CPCB-RPE1治疗并长达一年随访观察[69],结果显示,其中15名患者接受了复合体移植,有4名患者出现严重的眼部不良事件,包括视网膜下出血、水肿、局灶性视网膜脱离或RPE脱离,出血原因为在手术中和术后从视网膜切开部位漏出,通过修改手术方案这些症状得到缓解;15名患者接受移植后一年没有发生与移植、手术或免疫抑制相关的意外严重不良事件,也没有发生移植物迁移的迹象;5名患者BCVA提高了5个字母以上。2022年该团队为了检测CPCB-RPE1移植后是否产生免疫反应,在移植2年后进行了一系列检测[70],发现移植时经过短期的免疫抑制药物治疗可以避免视网膜炎、玻璃体炎、血管炎、脉络膜炎等免疫反应临床症状的发生。2023年Federal University of So Paulo公布了临床Ⅰ期研究结果(注册号:NCT02903576)[71],该研究将hESC-RPE悬液移植到12名晚期STGD患者中。术后未发生眼部炎症、眼内炎、视网膜脱离、眼出血、眼压升高、角膜水肿等手术相关不良事件。在1年的随访中未发生与hES-RPE移植相关的不良反应,即异常增生、排斥反应或严重的眼部或全身安全问题,所有患者手术眼的BCVA均无明显改善,可能与该疾病是晚期有关。2014年Lineage Cell Therapeutics进行了一项Ⅰ/Ⅱa期临床试验(注册号:NCT02286089),将制备的hESC-RPE产品OpRegen治疗24名干性AMD患者以评估其移植的安全性和耐受性(https://clinicaltrials.gov/)。Allen等[72]公布临床结果,所有患者中有9名患者在最后一次随访时BCVA保持稳定,目前的临床数据说明OpRegen具有良好的耐受性,长达5年的随访正在进行。2021年12月,Lineage Cell Therapeutics和Hoffmann-La Roche(OTCQX:RHHBY)的子公司Genentech达成了独家全球合作和许可协议,用于开发和商业化OpRegen用于治疗眼部疾病,交易金额高达6.7亿美元。根据协议,Lineage Cell Therapeutics将继续负责RG6501(OpRegen)的生产,Genentech将负责进一步临床开发和商业化,目前正在开展GA晚期干性AMD患者临床试验(注册号:NCT05626114)。

截至目前hESC-RPE的临床数据表明,hESC-RPE移植是安全,未发生移植细胞产生的严重不良事件,且大部分患者视力保持稳定或提高。hESC-RPE在RP患者中也开始临床试验,2019年Centre D'etude Des Cellules Souches启动临床Ⅰ/Ⅱ期研究(注册号:NCT03963154),在RP患者视网膜下移植hESC-RPE贴片以评估安全性与耐受性、贴片位置是否移动、视觉功能的改善等(https://clinicaltrials.gov/)。2020年中国北京同仁医院启动临床Ⅰ期研究(注册号:NCT03944239),在10名RP患者(18~80岁)视网下注射150000个hESC-RPE,为期1年随访以评估不良事件的发生和视觉功能的改善(https://clinicaltrials.gov/)。其他临床试验正在进行,目前所有hESC-RPE的临床试验共有23项(见表2)。

4.2hiPSC-RPE的临床应用研究进展

Souied等[43]首次将患者皮肤成纤维细胞来源的hiPSC分化为RPE,hiPSC-RPE细胞片层移植到2名晚期湿性AMD患者视网膜底部(临床备案号:UMIN000011929);77岁女性患者术后1年的观察中未发现免疫排斥反应以及其他不良反应,视力没有得到很大改善但也没有恶化,初次证明了hiPSC-RPE治疗的安全性,68岁男性患者因为检测到hiPSC-RPE的3个基因缺失突变,没有接受手术治疗;2019年Takagi等[73]针对UMIN000011929临床试验公布了77岁女性患者的术后4年随访结果,移植眼的hiPSC-RPE在4年后仍存活,没有发生任何不良事件及免疫排斥反应,视力保持稳定,没有显著改善可能是术前感光层严重受损,并含有纤维化瘢痕,使视力恢复的潜力有限。同时Takagi等也通過彩色眼底摄影、OCT、荧光素血管造影、吲哚青绿血管造影等评估77岁女性患者移植部位hiPSC-RPE的功能,发现具备支持脉络膜生长等功能。

2023年Maeda等[44]针对UMIN000011929这一临床试验公布77岁女性患者5年随访结果,术后5年hiPSC-RPE存活,未观察到术中并发症、肿瘤发生、移植失败、排斥反应或其他移植细胞严重并发症等。相比于自体移植,异体移植可以减少制备时间和降低成本。2020年,Sugita等[42]从hiPSC库中制备人类白细胞抗原(Human leukocyte Antigens, HLA)纯合子同种异体的hiPSC-RPE移植到具有相同HLA单倍型特征的5名湿性AMD患者(临床备案号:UMIN000026003),建立了两个评估和管理异体RPE移植免疫排斥反应的测试系统,即淋巴细胞移植物免疫反应(LGIR)测试和血清中RPE特异性抗体检测(RSA试验)。通过LGIR测试和RSA试验,发现在随访观察的1年内仅1/5患者表现出轻微免疫排斥症状,在联合使用局部类固醇药物后症状缓解。移植的hiPSC-RPE在1年观察期内是存活的,但部分患者观察到息肉样病变,而且由于移植的位置没有控制好,无法判断该治疗方法的疗效。

美国国家眼科研究所(National Eye Institute, NEI)正在进行一项Ⅰ/Ⅱa期试验(注册号:NCT04339764)(https://clinicaltrials.gov/),将患者的血细胞来源hiPSC分化为RPE,hiPSC-RPE细胞片层移植到AMD患者视网膜底部以评估安全性。2022年8月第一例干性AMD患者已完成移植(https://www.nei.nih.gov)。EyestemResearch是一家印度细胞治疗公司,异体hiPSC-RPE移植在动物模型中证明是安全的,并已首次开始人干性AMD患者临床试验(https://eyestem.com/)。法国TreeFrogTherapeutics(https://treefrog.fr/)和日本HealiosK.K.(https://www.healios.co.jp/en/)公司也開始尝试hiPSC-RPE治疗干性AMD患者。

截至目前hiPSC-RPE临床试验数据表明,hiPSC-RPE自体或异体移植是安全和可行的,没有移植hiPSC-RPE带来严重事件,且患者视力有所提高。其他hiPSC-RPE临床试验正在进行,目前hiPSC-RPE临床试验共有9项(见表3)。

综上所述,基于hiPSC-RPE的细胞移植治疗视网膜退行性疾病安全可行,但其治疗的有效性、长期性尚需有更多的临床试验数据支持。

5hPSC-RPE治疗的风险及挑战

hPSC-RPE为视网膜退行性疾病的治疗提供了新的思路,并初步显示出一定的发展前景,hPSC-RPE已经用于开展临床试验研究,但治疗的有效性和长期安全性的数据还远远不够,并且仍存在风险和挑战。

a)为了确保移植的hPSC-RPE安全,需要对hPSC-RPE进行临床前的验证,包括细胞纯度、基因组稳定性和致瘤性的评估。移植前必须确认参与多能性、早期发育和非上皮相关基因表达情况及没有细胞增殖标志物;在体外检测hPSC-RPE是否具有成熟RPE的正常功能[74]。至目前的临床研究数据,还未出现受试者眼睛中形成畸胎瘤、移植的hPSC-RPE细胞增殖和迁移到其他器官,也未发生因移植hPSC-RPE产生眼部严重不良事件。

b)移植后要确保hPSC-RPE细胞的存活率并具备完整功能,目前hPSC-RPE的细胞悬液移植和细胞片层移植均在临床上取得重大进展,RPE片层的制备比细胞悬液更复杂、成本更高,但RPE片层是一种成熟的、具有良好特性的细胞产品,具有体内RPE固有的形态和特性[75]。

c)手术本身带来的不良反应也是hPSC-RPE视网膜下移植安全评估的挑战。手术操作会给眼部带来创伤,如增殖性玻璃体视网膜病变,导致视力丧失的严重并发症包括视网膜脱离、眼内炎症和脉络膜上出血,轻微并发症包括脉络膜脱离、玻璃体出血、黄斑水肿、青光眼和视网膜裂孔等[76]。由于RPE贴片移植前手术侵入性更大,切口更大,RPE贴片移植手术并发症的风险一般高于RPE悬液移植,目前已有几例与手术相关的不良事件的报道[43,67-69]。

d)移植后免疫排斥的发生也是该治疗方法所面临的挑战。hESC细胞本身组织相容性复合体Ⅰ(Major histocompatibility complex Ⅰ, MHC Ⅰ)表达很低,但在体外分化阶段MHC Ⅰ表达会升高,移植到视网膜下腔在炎症微环境的影响下hESC-RPE的MHC Ⅰ表达也会升高[77]。hiPSC-RPE自体移植后虽然表现出较小的免疫反应,但在逆转录病毒介导重编程过程中可能会带来免疫排斥风险[78]。目前的临床试验中大多数移植采用免疫抑制剂药物避免免疫排斥的发生,但这会对老年人的身体产生一定的负担。MHC配型为hPSC-RPE细胞移植在解决免疫排斥问题方面提供了新思路[42],但仍需要很长的路要走。

参考文献:

[1]Thomas C J, Mirza R G, Gill M K. Age-related macular degeneration[J]. The Medical Clinics of North America, 2021, 105(3): 473-491.

[2]Lang M, Harris A, Ciulla T A, et al. Vascular dysfunction in retinitis pigmentosa[J]. Acta Ophthalmologica, 2019, 97(7): 660-664.

[3]Heath Jeffery R C, Chen F K. Stargardt disease: Multimodal imaging: A review[J]. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, 2021, 49(5): 498-515.

[4]Yip Henry K. Retinal stem cells and regeneration of vision system[J]. Anatomical Record, 2014, 297(1): 137-160.

[5]Chichagova V, Hallam D, Collin J, et al. Cellular regeneration strategies for macular degeneration: Past, present and future[J]. Eye, 2018, 32(5):946-971.

[6]Rohowetz Landon J, Peter K. Stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium cell therapy: Past and future directions[J]. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2023, 11:1098406.

[7]Akiba R, Takahashi M, Baba T, et al. Progress of iPS cell-based transplantation therapy for retinal diseases[J]. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology, 2023, 67(2):119-128.

[8]Devika B, Davide O, Mitra F, et al. Considerations for developing an autologous induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) replacement therapy [J].Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2023, 13(8): a041295.

[9]Lakkaraju A, Umapathy A, Tan L X, et al. The cell biology of the retinal pigment epithelium[J]. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 2020, 78: 100846.

[10]Lehmann G L, Benedicto I, Philp N J, et al. Plasma membrane protein polarity and trafficking in RPE cells: Past, present and future[J]. Experimental Eye Research_, 2014, 126: 5-15.

[11]Rudraraju M, Narayanan S P, Somanath P R. Regulation of blood-retinal barrier cell-junctions in diabetic retinopathy[J]. Pharmacological Research, 2020, 161: 105115.

[12]Rein D B, Wittenborn J S, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019[J]. JAMA Ophthalmology, 2022, 140(12): 1202-1208.

[13]Wong W L, Su X Y, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. The Lancet Global Health, 2014, 2(2): e106-e116.

[14]Li J Q, Welchowski T, Schmid M, et al. Prevalence and incidence of age-related macular degeneration in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. The British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2020, 104(8): 1077-1084.

[15]Somasundaran S, Constable I J, Mellough C B, et al. Retinal pigment epithelium and age-related macular degeneration: A review of major disease mechanisms[J]. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, 2020, 48(8): 1043-1056.

[16]Fritsche L G, Igl W, Bailey J N C, et al. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants[J]. Nature Genetics, 2016, 48(2): 134-143.

[17]Kanda A, Chen W, Othman M, et al. A variant of mitochondrial protein LOC387715/ARMS2, not HTRA1, is strongly associated with age-related macular degeneration[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104(41): 16227-16232.

[18]Fritsche L G, Loenhardt T, Janssen A, et al. Age-related macular degeneration is associated with an unstable ARMS2 (LOC387715) mRNA[J]. Nature Genetics, 2008, 40(7): 892-896.

[19]Ambati J, Fowler B J. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration[J]. Neuron, 2012, 75(1): 26-39.

[20]Sharma R, Bose D, Maminishkis A, et al. Retinal pigment epithelium replacement therapy for age-related macular degeneration: Are we there yet?[J]. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 2020, 60: 553-572.

[21]Selcuk S, Ebru E, Puren I, et al. Comparison of intravitreal injections of Ranibizumab and Aflibercept in neovascular age related macular degeneration[J]. Clinical & Experimental Optometry, 2021, 105(1): 55-60.

[22]Ricci F, Bandello F, Navarra P, et al. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration: therapeutic management and new-upcoming approaches[J].International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020, 21(21): 8242.

[23]Fabre M, Mateo L, Lamaa D, et al. Recent advances in age-related macular degeneration therapies[J]. Molecules, 2022, 27(16): 5089.

[24]Mania H, Sajjad M, Aslam Tariq M. Macular atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration: What is the link? Part I: A review of disease characterization and morphological associations[J].Ophthalmology and Therapy, 2019, 8(2): 235-249.

[25]Piotter E, McClements M E, MacLaren R E. Therapy approaches for stargardt disease[J]. Biomolecules, 2021, 11(8): 1179.

[26]Molday Robert S, Garces Fabian A, Fernandes S J, et al. Structure and function of ABCA4 and its role in the visual cycle and Stargardt macular degeneration[J]. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 2021, 89: 101036.

[27]Lenis T L, Hu J, Ng S Y, et al. Expression of ABCA4 in the retinal pigment epithelium and its implications for Stargardt macular degeneration[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2018, 115(47): E11120-E11127.

[28]Hu F Y, Gao F J, Li J K, et al. Novel variants of ABCA4 in Han Chinese families with Stargardt disease[J]. BMC Medical Genetics, 2020, 21(1): 213.

[29]Verbakel S K, van Huet R A C, Boon C J F, et al. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa[J]. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 2018, 66: 157-186.

[30]Daiger S P, Sullivan L S, Bowne S J. Genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa[J]. Clinical Genetics, 2013, 84(2): 132-141.

[31]Cehajic-Kapetanovic J, Xue K M, Martinez-Fernandez de la Camara C, et al. Initial results from a first-in-human gene therapy trial on X-linked retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in RPGR[J]. Nature Medicine, 2020, 26(3): 354-359.

[32]DiCarlo James E, Mahajan Vinit B, Tsang Stephen H. Gene therapy and genome surgery in the retina[J]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2018, 128(6): 2177-2188.

[33]Hinkle J W, Mahmoudzadeh R, Kuriyan A E. Cell-based therapies for retinal diseases: A review of clinical trials and direct to consumer cell therapy clinics[J]. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2021, 12(1): 538.

[34]Ahmed I, Johnston R J Jr, Singh M S. Pluripotent stem cell therapy for retinal diseases[J]. Annals of Translational Medicine, 2021, 9(15): 1279.

[35]Voisin A, Pnaguin A, Gaillard A, et al. Stem cell therapy in retinal diseases[J]. Neural Regeneration Research, 2023, 18(7): 1478.

[36]Peyman G A, Blinder K J, Paris C L, et al. A technique for retinal pigment epithelium transplantation for age-related macular degeneration secondary to extensive subfoveal scarring[J]. Ophthalmic surgery, 1991, 22(2): 102-108.

[37]Algvere P V, Berglin L, Gouras P, et al. Transplantation of RPE in age-related macular degeneration: Observations in disciform lesions and dry RPE atrophy[J]. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 1997, 235(3): 149-158.

[38]Weisz J M, Humayun M S, De Juan E Jr, et al. Allogenic fetal retinal pigment epithelial cell transplant in a patient with geographic atrophy[J]. Retina, 1999, 19(6): 540-545.

[39]Del Priore L V, Kaplan H J, Tezel T H, et al. Retinal pigment epithelial cell transplantation after subfoveal membranectomy in age-related macular degeneration: Clinicopathologic correlation[J]. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 2001, 131(4): 472-480.

[40]Schwartz S D, Hubschman J P, Heilwell G, et al. Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: a preliminary report[J]. Lancet, 2012, 379(9817): 713-720.

[41]Jin Z B, Gao M L, Deng W L, et al. Stemming retinal regeneration with pluripotent stem cells[J]. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 2019, 69: 38-56.

[42]Sugita S, Mandai M, Hirami Y, et al. HLA-matched allogeneic iPS cells-derived RPE transplantation for macular degeneration[J]. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2020, 9(7): 2217.

[43]Souied E, Pulido J, Staurenghi G. Autologous induced stem-cell-derived retinal cells for macular degeneration[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2017, 377(8): 792.

[44]Maeda T, Takahashi M. IPSC-RPE in retinal degeneration: Recent advancements and future perspectives[J]. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2023,13(8):a041308.

[45]Thomson J A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro S S, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts[J]. Science, 1998, 282(5391):1145-1147.

[46]Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors[J]. Cell, 2006, 126(4): 663-676.

[47]Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors[J]. Cell, 2007, 131(5): 861-872.

[48]Yu J Y, Vodyanik M A, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells[J]. Science, 2007, 318(5858): 1917-1920.

[49]Plaza Reyes A, Petrus-Reurer S, Antonsson L, et al. Xeno-Free and defined human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells functionally integrate in a large-eyed preclinical model[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2016, 6(1): 9-17.

[50]Tanaka T, Yokoi T, Tamalu F, et al. Generation of retinal ganglion cells with functional axons from human induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 8344.

[51]Mellough Carla B, Evelyne S, Inmaculada M G, et al. Efficient stage-specific differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells toward retinal photoreceptor cells[J]. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio), 2012, 30(4): 673-686.

[52]Klimanskaya I, Hipp J, Rezai K A, et al. Derivation and comparative assessment of retinal pigment epithelium from human embryonic stem cells using transcriptomics[J]. Cloning and Stem Cells, 2004, 6(3): 217-245.

[53]Regent F, Morizur L, Lesueur L, et al. Automation of human pluripotent stem cell differentiation toward retinal pigment epithelial cells for large-scale productions [J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 10646.

[54]Fabio M, Aishwarya B, Nickolas T, et al. Rapid generation of purified human RPE from pluripotent stem cells using 2D cultures and lipoprotein uptake-based sorting [J].Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2020, 11(1): 47.

[55]Zahabi A, Shahbazi E, Ahmadieh H, et al. A new efficient protocol for directed differentiation of retinal pigmented epithelial cells from normal and retinal disease induced pluripotent stem cells [J].Stem Cells and Development, 2012, 21(12): 2262-2272.

[56]Hirami Y, Osakada F, Takahashi K, et al. Generation of retinal cells from mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells [J]. Neuroscience Letters, 2009, 458(3): 126-131.

[57]Lu B, Malcuit C, Wang S M, et al. Long-term safety and function of RPE from human embryonic stem cells in preclinical models of macular degeneration[J]. Stem Cell, 2009, 27(9): 2126-2135.

[58]Liu Y, Xu H W, Wang L, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium transplants as a potential treatment for wet age-related macular degeneration[J]. Cell Discovery, 2018, 4: 50.

[59]Limnios Ioannis J, Qian C Y, Skabo Stuart J, et al. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to retinal pigment epithelium under defined conditions[J]. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2021, 12(1):248.

[60]Petrus-Reurer S, Lederer A R, Baqu-Vidal L, et al. Molecular profiling of stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelial cell differentiation established for clinical translation[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2022, 17(6): 1458-1475.

[61]Idelson M, Alper R, Obolensky A, et al. Immunological properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2018, 11(3): 681-695.

[62]Schwartz S D, Regillo C D, Lam B L, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in patients with age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt's macular dystrophy: Follow-up of two open-label phase 1/2 studies[J]. Lancet, 2015, 385(9967): 509-516.

[63]Mehat M S, Sundaram V, Ripamonti C, et al. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells in macular degeneration[J]. Ophthalmology, 2018, 125(11): 1765-1775.

[64]Song W, Park K M, Kim H J, et al. Treatment of macular degeneration using embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium: Preliminary results in Asian patients[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2015, 4(5): 860-872.

[65]Youngje S, Ji L, Jinjung C, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of subretinal transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in Asian Stargardt disease patients[J]. The British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2020, 105(6): 829-837.

[66]Li S Y, Liu Y, Wang L, et al. A phase I clinical trial of human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells for early-stage Stargardt macular degeneration: 5-years' follow-up[J]. Cell Proliferation, 2021, 54(9): e13100.

[67]da Cruz L, Fynes K, Georgiadis O, et al. Phase 1 clinical study of an embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium patch in age-related macular degeneration[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2018, 36(4):328-337.

[68]Kashani A H, Lebkowski J S, Rahhal F M, et al. A bioengineered retinal pigment epithelial monolayer for advanced, dry age-related macular degeneration[J]. Science Translational Medicine, 2018, 10(435): eaao4097.

[69]Kashani A H, Lebkowski J S, Rahhal F M, et al. One-year follow-up in a phase 1/2a clinical trial of an allogeneic RPE cell bioengineered implant for advanced dry age-related macular degeneration[J]. Translational Vision Science & Technology, 2021, 10(10): 13.

[70]Kashani A H, Lebkowski J S, Hinton D R, et al. Survival of an HLA-mismatched, bioengineered RPE implant in dry age-related macular degeneration[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2022, 17(3):448-458.

[71]Brant Fernandes M Rodrigo A, Lojudice Fernando H, Zago R L, et al. Transplantation of subretinal stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium for stargardts disease: A phase I clinical trial[J]. Retina, 2023, 43(2): 263-274.

[72]Allen C Ho, Eyal Banin, Adiel Barak, et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Phase 1/2a Clinical Trial of Transplanted Allogeneic Retinal Pigmented Epithelium (RPE, OpRegen) Cells in Advanced Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) [J]. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2022, 63(7):1862.

[73]Takagi S, Mandai M, Gocho K, et al. Evaluation of transplanted autologous induced pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in exudative age-related macular degeneration[J]. Ophthalmology Retina, 2019, 3(10): 850-859.

[74]纳涛,王磊,郝捷,等.人胚胎干细胞来源的视网膜色素上皮細胞质量控制研究[J]. 生命科学, 2018, 30(3): 248-260.

[75]Rajendran Nair Deepthi S, Zhu D H, Ruchi S, et al. Long-term transplant effects of iPSC-RPE monolayer in immunodeficient RCS rats[J]. Cells, 2021, 10(11): 2951.

[76]Shields R A, Ludwig C A, Powers M A, et al. Surgical timing and presence of a vitreoretinal fellow on postoperative adverse events following pars plana vitrectomy[J]. European Journal of Ophthalmology, 2020, 30(1): 81-87.

[77]Drukker M, Katz G, Urbach A, et al. Characterization of the expression of MHC proteins in human embryonic stem cells[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2002, 99(15): 9864-9869.

[78]Araki R, Uda M, Hoki Y, et al. Negligible immunogenicity of terminally differentiated cells derived from induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cells[J]. Nature, 2013, 494(7435): 100-104.

(责任编辑:张会巍)

收稿日期:2023-06-18中文收稿日期网络出版日期:2023-11-02网络出版日期

基金项目:企业委托研发项目(21040400-J) 中文基金项目

作者简介:郭艳(1998—),女,甘肃通渭人,硕士研究生,主要从事多能干细胞方面的研究。

中文作者简介

通信作者:吴月红,E-mail:wuyuehong2003@163.com中文通信作者