“冷”/“热”执行功能缺陷影响ADHD儿童核心症状的作用机制*

2023-11-04王雪珂冯廷勇

王雪珂 冯廷勇

“冷”/“热”执行功能缺陷影响ADHD儿童核心症状的作用机制*

王雪珂 冯廷勇

(西南大学心理学部, 重庆 400715)

注意缺陷多动障碍(ADHD)是一种以注意缺陷和(或)多动、冲动为核心症状的神经发育障碍, 与前额叶发育异常所致的执行功能缺陷密切相关。基于此, 从神经−认知−行为的发展途径提出执行功能缺陷可能是认知层面上导致ADHD核心症状的发病机理, 其中与背侧前额叶相关的“冷”执行功能缺陷可能是导致注意缺陷核心症状的主导因素, 而与腹内侧前额叶相关的“热”执行功能缺陷可能是导致多动、冲动核心症状的主导因素。一方面, “冷”执行功能缺陷主要引起工作记忆表征维持失败、抑制控制能力不足、认知转换困难等方面, 这些缺陷进一步导致了个体在注意持续、注意选择和注意转移上受到限制; 另一方面, “热”执行功能缺陷则带来厌恶延迟、奖赏加工异常、动机失调等问题, 使得个体行为抑制失败, 更容易做出冲动性选择, 从而表现出多动、冲动等核心症状。未来研究应进一步检验和完善“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷影响ADHD核心症状的理论模型以及从认知神经层面上提供更多的实证证据, 同时还需从生态层面考察“冷”和“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD核心症状的交互影响, 并基于执行功能开发对ADHD核心症状具有个性化、精准化、长效化的干预方案。

注意缺陷多动障碍, 执行功能缺陷, 核心症状, 前额叶皮层, 作用机制

1 引言

注意缺陷多动障碍(Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, ADHD)是源于儿童期的一种神经发育障碍, 其主要特征是与发育水平不相称的注意缺陷和(或)冲动多动, 并伴有学习或社交等单一或多个功能损害(American Psychiatric Association, 2013)。全球儿童患病率高达7.2% (Sayal et al., 2018; Wolraich et al., 2019), 而我国最新ADHD患病率为6.4% (Li et al., 2022), 其中50.9%的ADHD儿童症状可持续至成年期(Agnew-Blais et al., 2016; Franke et al., 2018; 李廷玉等, 2020; Sibley et al., 2016), 所带来的危害涉及生命全周期(Faraone et al., 2015; Forte et al., 2019; Nigg et al., 2020; Retz et al., 2021)。执行功能缺陷被看作是ADHD的主要认知缺陷 (Kofler et al., 2019; Silverstein et al., 2020), 它不仅是预测疾病发展、评估诊断和干预治疗的敏感指标, 也是阻碍ADHD儿童学习能力和社会适应的主要因素。ADHD的病因与发病机制至今尚不明确, 但越来越多研究指出ADHD核心症状与其脑结构/ 功能连接异常密切相关(Faraone et al., 2021; Hoogman et al., 2017)。然而神经异常导致ADHD儿童核心症状背后的潜在心理机制尚不清楚(Hinshaw, 2018; Mueller et al., 2017; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2022), 尤其是与前额叶异常发育有关的执行功能缺陷作为ADHD的基本认知缺陷和内表型, 是如何影响ADHD不同核心症状产生的。因此, 从执行功能缺陷的角度探究ADHD儿童发病机理, 并试图搭建ADHD儿童神经发育异常与核心症状之间的认知桥梁, 对于该疾病的早期识别、诊断及如何有效地临床干预具有重要的科学价值和实践意义。

基于大脑前额叶功能差异, 执行功能可分为“冷”、“热”两个不同成分(Zelazo & Carlson, 2012; Zelazo & Müller, 2012)。其中, “冷”执行功能主要涉及背外侧前额叶、腹外侧前额叶等脑区功能, 以相对抽象、去情境化的纯认知加工为主, 包括工作记忆、抑制控制、认知灵活性等子成分; “热”执行功能则指在高度情感/动机卷入下的认知加工, 包括延迟满足、情感决策等能力, 与腹内侧前额叶、眶额叶等脑区活动有关(Antonini et al., 2015; Crone & Steinbeis, 2017; Zelazo & Carlson, 2012)。ADHD的双通道模型理论(The Dual-Pathway Model)提出了导致ADHD病因的两条独立通道, 包括与多巴胺系统的中央−皮层分支相关的认知控制通道, 以及与奖赏回路的中央−边缘多巴胺分支相关的动机发展通道(Sonuga-Barke, 2002; Sonuga-Barke, 2003; Shen et al., 2020)。虽然该理论尚未明确表述执行功能缺陷与ADHD不同核心症状之间的关系, 但它为从“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷角度思考ADHD两大核心症状的发病机理提供了很好的启示。并且进一步研究证据发现, ADHD儿童的注意缺陷核心症状更多源于“冷”执行功能缺陷, 多动冲动则主要与“热”执行功能缺陷有关(Castellanos & Aoki, 2016; Shakehnia et al., 2021)。也就是说, “冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷可能是导致ADHD两大核心症状的独立途径, 并带来不同的行为表现和发展结果(Landis et al., 2021; Mueller et al., 2017; Pauli-Pott et al., 2019)。此外, 从发展性精神病理学(The Developmental Psychopathology)视角来看, ADHD是一种神经发育障碍, 在遗传与环境的相互作用下其早期神经发育进程受阻, 从而导致个体认知能力存在缺陷或不足, 这些缺陷或不足又会进一步增加ADHD儿童患病风险, 包括出现核心症状等异常行为表现(McLaughlin, 2016; Zelazo, 2020)。可见, 执行功能缺陷可能是神经发育异常导致ADHD核心症状背后的认知机制。因此, 有必要从神经−认知−行为多层面的视角出发, 深入探索“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD儿童两大核心症状的影响及其作用机制, 以进一步探明ADHD的本质和发病机理, 为个性化精准干预提供循证依据。

近年来, 执行功能缺陷与ADHD核心症状之间相关性的研究已取得迅速发展(Groves et al., 2022; Karalunas et al., 2021; Kofler et al., 2019; Shakehnia et al., 2021; Silverstein et al., 2020)。然而, 关于执行功能缺陷影响ADHD不同核心症状的具体作用机制目前仍缺乏全面和深入的分析与讨论。基于此, 本文以“冷”、“热”执行功能为主线, 首先试图解释执行功能缺陷可能是认知层面上导致ADHD核心症状的发病机理; 其次, 围绕执行功能缺陷为何影响ADHD儿童两大核心症状展开讨论; 然后, 重点阐述了“冷”、“热”执行功能各子成分缺陷影响ADHD儿童两大核心症状可能存在的作用机制; 最后, 对执行功能缺陷与ADHD核心症状之间关系的未来研究方向进行了展望。

2 执行功能缺陷是ADHD儿童的行为特点还是发病机理?

执行功能指的是自上而下地协调和控制个体思想、行为和情绪, 以实现目标导向的一系列高级认知过程(Diamond, 2013; Zelazo, 2015)。有力证据表明, 执行功能缺陷在ADHD群体中普遍存在着, 且可作为临床诊断标准之一(Barkley, 1997; Faraone et al., 2015; Kofler et al., 2019; Nigg et al., 2020)。目前关于ADHD执行功能缺陷的研究大都聚焦于行为特点或发展规律, 或将执行功能缺陷看作是ADHD核心症状的外在行为表现, 而忽视了执行功能缺陷在ADHD发育进程中的关键作用。尤其是在解释ADHD核心症状出现时, 执行功能缺陷是ADHD儿童的行为特点还是发病机理目前仍不清楚。美国国立心理健康研究所倡议的RDoC (Research Domain Criteria, 研究领域标准), 通过整合多个学科领域(如遗传学、神经科学和心理行为等), 试图提供一个更全面的框架来理解精神类疾病在心理或神经生物学系统(而不仅基于行为症状)中的发病机理。因此, 想要全面系统地解释ADHD核心症状及探索其发病机理时, 理应考虑到RDoC框架, 并结合神经、认知和行为等多个层面。

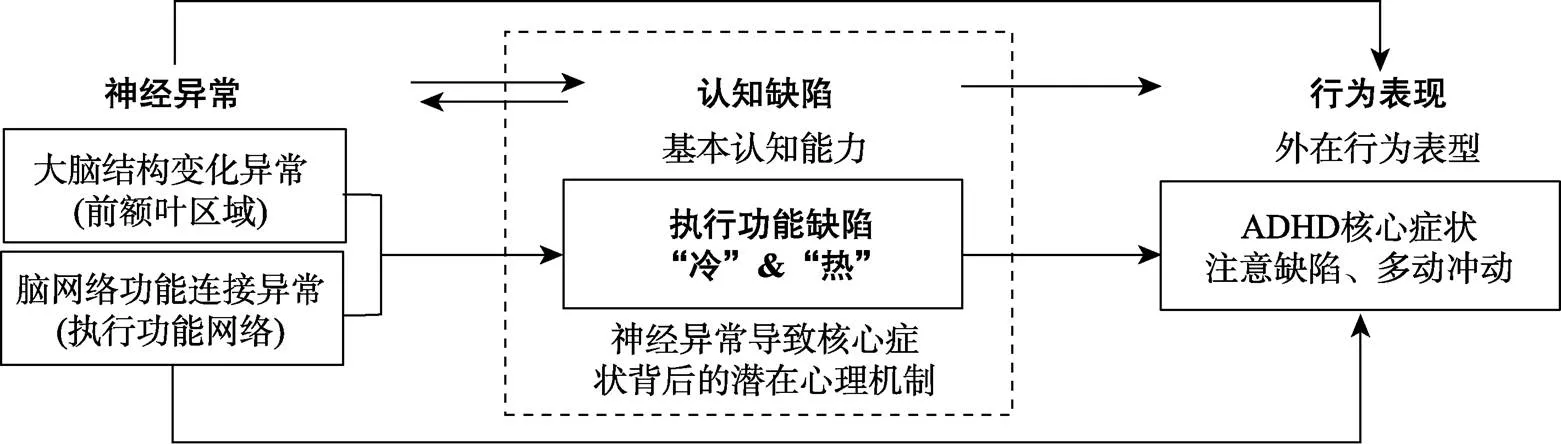

具体而言, 《精神疾病诊断与统计手册》第五版(The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, DSM-5)中明确指出ADHD是一种神经发育性疾病, 且在大脑结构和功能连接上均存在异常(Cortese et al., 2021; Hoogman et al., 2019; Hoogman, 2020; Thapar et al., 2017)。尤其是ADHD儿童在前额叶皮层上的发育延迟或不足, 不仅是导致核心症状出现的生理基础, 还与执行功能缺陷密切相关(Shaw et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2013; Yasumura et al., 2019)。元分析研究发现, ADHD患者在执行功能任务下(包括Stop-Signal、Go/No-Go、Stroop和N-back等任务范式)的额叶区域均表现出持续的异常激活状态(Hart et al., 2013; Lukito et al., 2020; Norman et al., 2016)。除了前额叶的脑结构与功能异常外, 脑网络功能异常也是ADHD儿童核心症状的一个强有力的影响因素(Cai et al., 2018; Sripada et al., 2014)。其中, 以前额叶为中心的执行控制网络以及其功能连接在ADHD患者中总体呈现减弱的特征, 并与注意不集中等核心症状的严重程度显著相关(Cai et al., 2021; Ryan et al., 2022)。从神经基础层面来看, ADHD儿童核心症状是由大脑结构和功能的异常变化所引起的, 尤其是与执行功能相关的前额叶皮层和执行控制网络功能的异常。同时, 执行功能作为一种底层认知能力, 自上而下地参与、指导或协调其他认知过程, 并在未来的学业表现、有意行为和社会适应等方面均起到决定性的作用(Spiegel et al., 2021; Zelazo, 2015)。执行功能的发展不足或缺陷, 不仅直接导致个体在日常生活中的异常表现, 带来注意不集中、过度活动、冲动等异常行为的出现; 若不加以干预, 这种不足或缺陷还会随着成长反过来影响个体的大脑结构发育与功能可塑性, 从而强化神经层面的异常, 进一步加剧ADHD儿童核心症状等异常行为的表现。因此, 这些神经和认知层面上的证据表明, ADHD是一种神经发育障碍, 尤其表现在与执行功能相关的前额叶皮层发育延迟和执行控制网络的功能连接异常, 这使得个体在执行功能上发展不足(认知缺陷), 进而导致注意缺陷和(或)多动冲动核心症状等异常行为表现的出现。

结合图1来看, 从神经异常到认知缺陷再到行为特点这一发展途径的视角可得, 执行功能缺陷可能是神经异常导致ADHD核心症状背后的认知机制, 并在神经发育异常与核心症状之间起到认知桥梁作用。总之, 本文遵循RDoC框架并结合发展性精神病理学的发展途径推断出, 执行功能缺陷不仅是ADHD儿童的行为特点, 更重要的可能是认知层面上导致ADHD核心症状出现的发病机理。那么为什么执行功能缺陷能够影响ADHD核心症状, 以及“冷”、“热”执行功能成分是否影响不同的核心症状呢?下面将围绕执行功能缺陷如何影响ADHD儿童不同核心症状展开讨论。

3 “冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD不同核心症状的影响

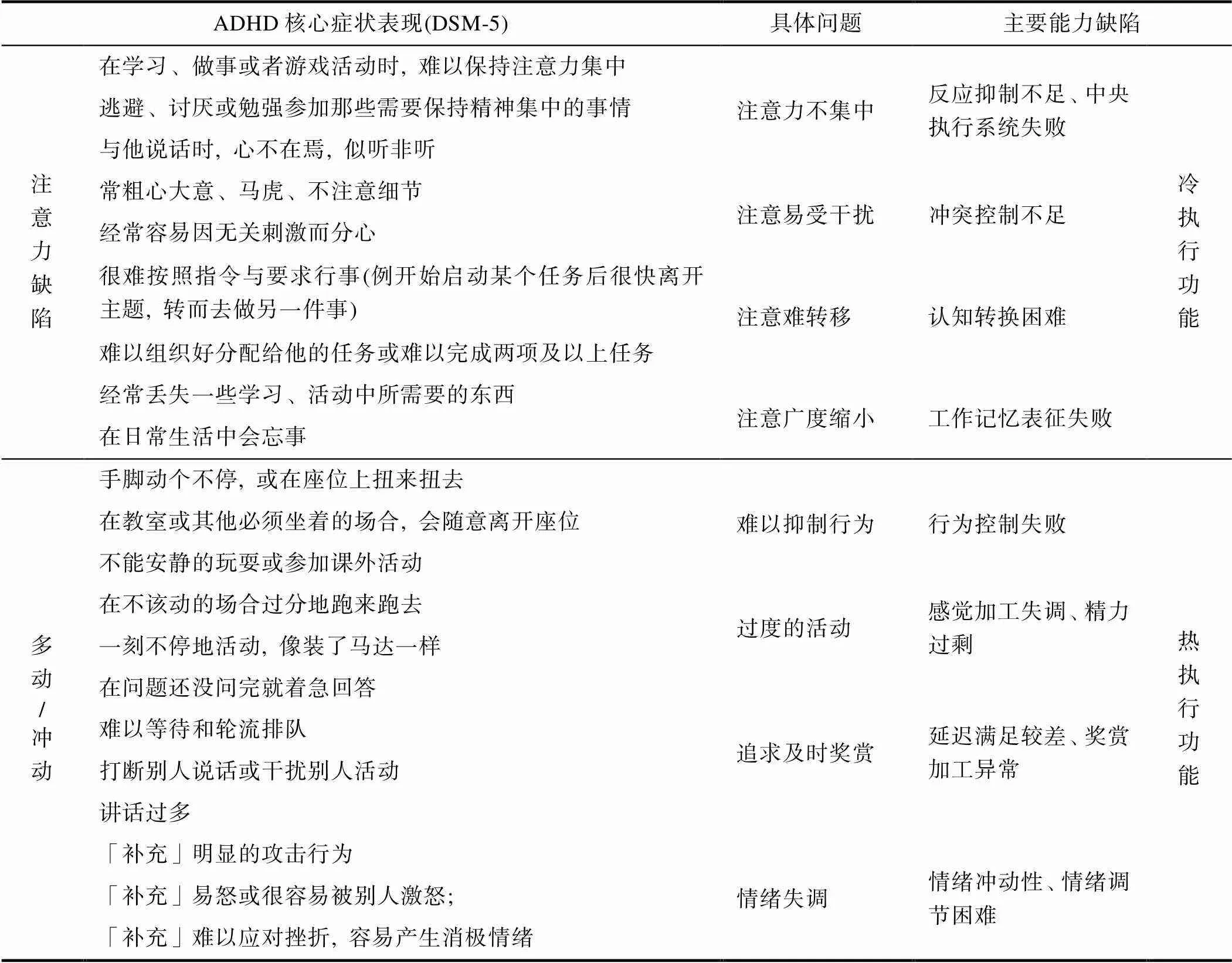

ADHD儿童的主要核心症状包括注意缺陷和多动冲动(DSM-5, APA, 2013)。其中, 注意缺陷的异常行为表现通常为难以保持注意集中、粗心大意、行为涣散、缺乏组织性等, 具体体现在注意不集中、注意易受干扰、注意难以转移、注意广度缩小等注意问题上; 多动冲动的异常行为表现通常为坐立不安、一刻不停地活动、难以等待、干涉他人活动等, 具体体现在难以抑制行为、过度的活动、追求及时奖赏、情绪失调等行为和情绪问题上(见表1)。为解释ADHD儿童所存在的这些异常行为表现, 双通道模型理论提出了导致ADHD病因的两条独立通路, 包括认知控制通路和动机发展通路(Sonuga-Barke, 2002)。一方面, 与前额叶皮层−纹状体等背侧执行回路相关的抑制控制不足导致ADHD儿童在认知和行为上的失调; 另一方面, 与眶额皮质−纹状体等腹侧奖赏回路相关的延迟满足能力的缺陷使得ADHD儿童存在动机上的失调(Shen et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2018)。尽管双通道模型理论尚未明确表述执行功能缺陷与ADHD不同核心症状之间的关系, 但后续研究者普遍认为双通道模型的两条通路与执行功能的“冷”、“热”不同成分缺陷密切相关, 且具有一定对应性。其中“冷”执行功能缺陷对应的是认知控制通路, “热”执行功能缺陷则对应的是动机发展通路(Geurts et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2018; 张微等, 2010)。由此, ADHD儿童异常行为表现的出现暗示了其相关认知能力的受损, 尤其是“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷。

图1 影响ADHD核心症状的神经−认知−行为发展途径图

表1 ADHD儿童不同核心症状的异常行为表现及主要执行功能缺陷

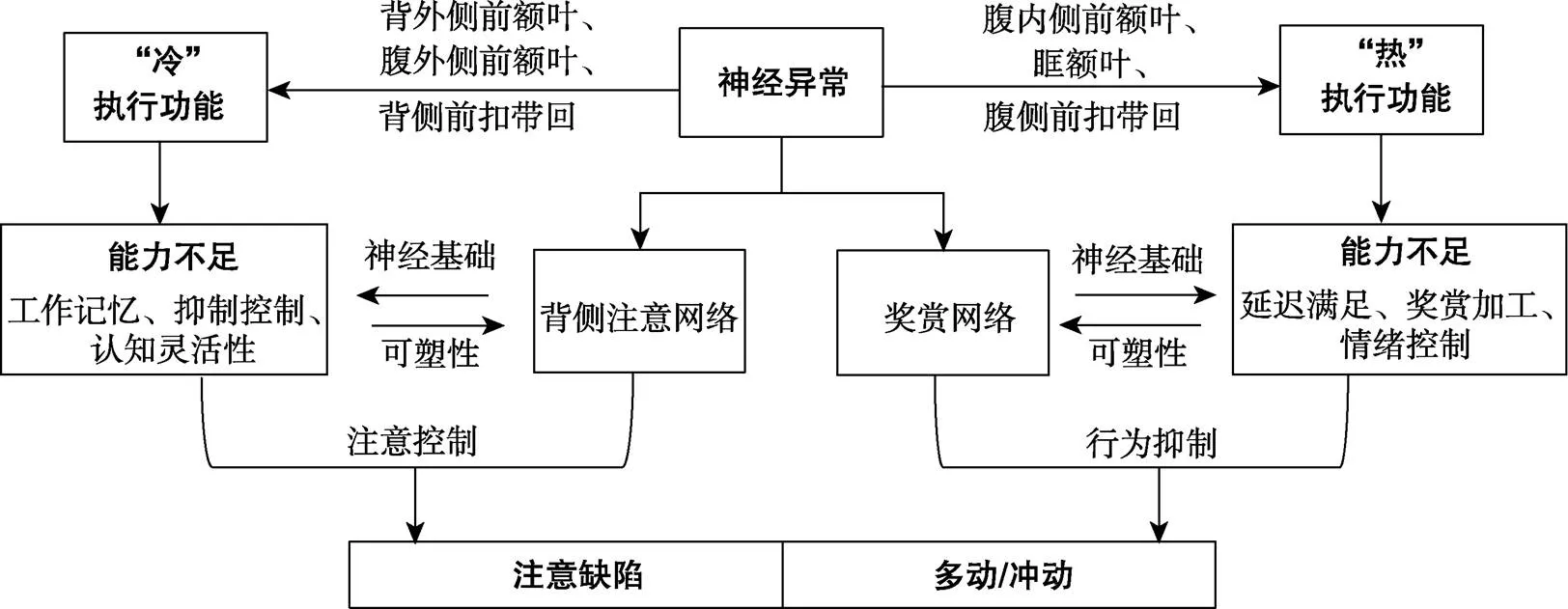

那么为什么执行功能缺陷能够影响ADHD不同核心症状呢?为解答这个问题, 可以从神经基础和认知层面分析“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD不同核心症状的影响。首先, “冷”执行功能涉及的脑区包括背外侧前额叶、腹外侧前额叶、背侧前扣带回等区域, 进行自上而下的认知控制过程; “热”执行功能与腹内侧前额叶、眶额叶、腹侧前扣带回等脑区活动有关, 主要涉及动机或情感成分卷入下的认知加工过程(Crone & Steinbeis, 2017; Moriguchi, 2021; Zelazo & Carlson, 2012)。大量研究表明, ADHD儿童存在“冷”执行功能缺陷(Barkley, 1997; Kofler et al., 2019; Pievsky & McGrath, 2018)。“冷”执行功能的各个子成分, 如工作记忆、抑制控制和认知灵活性等都已被证明与ADHD核心症状相关(Kofler, Harmon et al., 2018; Mueller et al., 2017)。并且, 研究发现“冷”执行功能缺陷对ADHD注意缺陷核心症状的影响更大(Irwin et al., 2021; Shakehnia et al., 2021; Silverstein et al., 2020)。例如工作记忆不足会导致粗心大意, 容易健忘; 抑制控制失败可能带来分心, 注意力不集中; 认知灵活性缺陷可能导致缺乏组织性, 注意难以转移等。此外, “冷”执行功能所涉及的关键脑区也是背侧注意网络的核心节点(如背外侧前额叶等), 参与个体的有意注意加工过程(Lemire-Rodger et al., 2019; Petersen & Posner, 2012)。除“冷”执行功能缺陷外, 注意网络的异常也会进一步加剧ADHD注意不集中等核心症状的出现。因此可知, “冷”执行功能缺陷所带来的能力不足及其异常的神经基础(背侧注意网络)共同影响ADHD注意缺陷核心症状的出现。其次, ADHD儿童也存在显著的“热”执行功能缺陷。“热”执行功能指的是在情感或动机高度卷入下进行灵活评估和风险决策的能力, 其缺陷往往被认为与ADHD儿童多动冲动的核心症状相关(Colonna et al., 2022; Dekkers et al., 2016; Shakehnia et al., 2021; Tegelbeckers et al., 2018)。例如, ADHD儿童难以抑制自己的行为, 追求及时奖赏, 并在日常生活中表现出情绪失调等异常行为表现, 很可能就是“热”执行功能缺陷所导致的(Bunford et al., 2022; Colonna et al., 2022; Petrovic & Castellanos, 2016)。与“热”执行功能相关的大脑区域也是奖赏网络的关键脑区(如眶额叶、腹内侧前额叶等), 参与个体的奖赏加工和自我情绪调控过程(Cubillo et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2019)。并且研究发现, ADHD儿童奖赏网络与其他脑区连接不平衡, 尤其是与执行控制网络以及相关脑区的功能连通性下降, 这种异常可能是多动冲动核心症状背后的神经机制(Dias et al., 2015; von Rhein et al., 2017)。因此, ADHD多动冲动核心症状可能是由于“热”执行功能缺陷所表现出的能力不足及其异常神经基础共同导致的。

综上所述, 结合理论和实证研究, 本文指出“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷可能是导致ADHD不同核心症状的两条认知途径。具体来看, 与背外侧额叶异常相关的“冷”执行功能缺陷, 会导致个体在面对任务时表现出能力不足(如难以对抗干扰, 难以维持记忆表征等), 进而出现注意控制失败; 与腹内侧额叶异常相关的“热”执行功能缺陷, 则会带来厌恶延迟、奖赏异常等能力上的问题, 进而表现出行为抑制失败和动机失调; 同时, 执行功能缺陷的异常神经基础也是核心脑网络(如背侧注意网络、奖赏网络)的关键节点或区域, 参与注意加工和奖赏处理等过程。这些脑网络的异常进一步影响个体的注意控制和行为抑制能力, 共同导致ADHD注意缺陷、多动冲动不同核心症状的出现(如图2所示)。

4 “冷”/“热”执行功能缺陷影响ADHD不同核心症状的作用机制

前文已提出“冷”、“热”执行功能可能是导致ADHD不同核心症状的两条认知途径, 并带来不同的行为表现和发展结果。其中与背外侧额叶相关的“冷”执行功能缺陷可能是ADHD儿童注意缺陷核心症状的主导因素, 与腹内侧额叶相关的“热”执行功能缺陷可能是导致ADHD儿童多动冲动核心症状的主要因素。接下来将重点阐述“冷”、“热”执行功能各子成分缺陷如何影响ADHD不同核心症状的出现及其具体的作用机制。

4.1 “冷”执行功能各子成分缺陷影响ADHD注意缺陷核心症状的作用机制

“冷”执行功能通过相应的能力调节注意以控制行为, 使行为在解决问题时更具适应性、计划性和专注性(Zelazo, 2020)。若“冷”执行功能存在缺陷, 则导致目标导向以及注意控制的失败, 具体表现在注意持续、选择、分配等方面上。通常“冷”执行功能包括三个核心子成分, 包括工作记忆、抑制控制和认知灵活性(Diamond, 2013; Miyake et al., 2000)。下面将围绕这三个子成分展开讨论影响ADHD注意缺陷核心症状的具体作用机制。

图2 “冷”、“热”执行功能影响ADHD不同核心症状的路径图

(1)工作记忆影响ADHD注意缺陷核心症状

工作记忆是指个体在执行认知任务过程中, 对信息进行暂时存储与加工的资源有限的记忆系统(Baddeley, 2012)。它不仅包括负责暂存和整合记忆表征信息的情景缓冲器, 还包括负责抑制无关信息、引导注意目标信息的中央执行系统, 这与选择性注意密切相关(Ahmed & de Fockert, 2012; Luck & Vogel, 2013)。一方面, 在工作记忆中的信息表征会自上而下地捕获目标刺激, 从而引导注意选择过程; 另一方面, 中央执行系统有助于忽视或抑制无关信息, 选择性地将资源分配到目标相关的刺激上, 有利于注意选择(Gazzaley & Nobre, 2012; Greene et al., 2015)。此外, 额顶网络是工作记忆系统中的关键区域, 它的激活可以促进目标信息的保持和加工(Lamichhane et al., 2020; Soto et al., 2013)。研究发现, 额顶网络既与工作记忆的表征维持有关, 还参与注意控制过程(Bahmani et al., 2019; Wallis et al., 2015), 尤其是背外侧前额叶的激活与工作记忆中的注意选择过程有关(Panichello & Buschman, 2021; Quentin et al., 2019)。因此, 有理由推断出ADHD儿童工作记忆的缺陷会通过工作记忆表征和中央执行系统影响个体的注意选择过程。事实上, 研究已表明工作记忆缺陷是ADHD儿童较为显著的认知缺陷, 且对注意缺陷核心症状的预测力度最大(Fosco et al., 2020; Irwin et al., 2021; Ramos et al., 2020)。具体来看, ADHD儿童缺乏信息存储以及在一定时间内维持记忆信息表征的能力, 因此导致其更容易丢失完成任务所需的关键信息, 无法选择正确的目标信息; 中央执行系统的缺陷则使得ADHD儿童难以抑制无关信息, 增加认知控制的负荷, 自上而下的注意控制受到限制(Jacobson et al., 2011; Kofler, Soto et al., 2020; Re et al., 2016)。在这种情况下, 课堂中的ADHD儿童很容易将注意力转移到与课堂内容无关的内部想法或者外部刺激上, 并表现出与选择性注意相关的缺陷(Rapport et al., 2009)。神经影像的研究也发现, 工作记忆任务中ADHD儿童激活异常的脑区集中于背外侧前额叶、内侧额下回、扣带回、顶叶等区域, 这些脑区也参与注意选择和控制过程(Ko et al., 2013; Samea et al., 2019)。Luo等人(2019)采用视觉工作记忆范式引出经典的注意过程(包括注意选择−维持−匹配阶段), 并以N2pc (posterior contralateral N2)和CDA (contralateral delay activity)成分作为指标, 通过脑电行为同步分析有效区分出注意选择过程和工作记忆维持过程。结果发现ADHD患者选择性注意与工作记忆缺陷密切相关, 即当记忆负荷增加时, ADHD患者的工作记忆难以维持并导致任务中注意选择效率降低(Luo et al., 2019)。总体而言, ADHD儿童工作记忆不足影响注意缺陷核心症状的作用机制, 主要表现在难以维持工作记忆表征, 以及中央执行系统自上而下的控制失败, 从而不利于注意选择过程, 出现注意易受干扰、注意不集中等异常行为表现。

(2) 抑制控制影响ADHD注意缺陷核心症状

抑制控制是个体有意抑制那些强烈的内/外在干扰信息, 以至于对目标做出正确反应的能力(Aron et al., 2004)。根据干扰刺激的不同, 可分为反应抑制(即行为层面的抑制能力)和冲突控制(干扰抑制, 即认知层面的抑制能力) (Diamond, 2013)。其中, 反应抑制指的是抑制住对外界干扰信息的不恰当行为反应, 并将注意保持在目标信息上; 冲突控制能力又称为干扰抑制能力, 主要指的是抑制大脑中出现的冲突信息, 依然坚持正确反应(Hung et al., 2018)。也就是说, 如果抑制控制存在缺陷, 个体将难以抑制对无关刺激(如外在干扰物、内在无关想法)的注意或行为反应, 导致注意的持续性受到限制。多数研究已发现ADHD儿童在抑制控制能力上存在困难。例如, 在Stop-Signal、Go/No-Go等反应抑制任务中, ADHD儿童反应时更长、错误率较高(Fosco et al., 2019; Hart et al., 2013); 在Stroop、Simon等干扰控制任务中, ADHD儿童在不一致试次下表现出更差的反应时和正确率(Borella et al., 2013; Mullane et al., 2009)。抑制控制与ADHD儿童注意缺陷核心症状之间的密切关系得到普遍认可(Janssen et al., 2018; Mueller et al., 2017)。行为研究发现, ADHD在儿童时期表现出的反应抑制不足能够预测其在青少年期注意不集中症状的发展, 并且抑制不足使得注意缺陷随年龄改善的幅度较小(DeRonda et al., 2021)。从神经影像的视角来看, ADHD患者在反应抑制任务下右侧额下回、顶叶、纹状体等脑区的激活存在异常(Thornton et al., 2018; van Rooij et al., 2015)。其中, 额下回不仅参与抑制信号的启动和处理, 也与腹侧注意网络和颞顶联合区相关, 负责维持注意控制; 顶叶区域则主要参与反应抑制期间的注意重新定向和任务目标维持(Cai & Leung, 2011; Fabio & Urso, 2014)。此外, ADHD患者在反应抑制网络之间也表现出较低的连通性, 且与ADHD核心症状严重程度显著相关(van Rooij et al., 2015)。Cai等人(2021)发现Go/No-GO任务诱发的背侧前扣带回与腹外侧前额叶之间的有效连通性不仅与反应抑制能力呈显著正相关, 还能预测ADHD儿童注意不集中缺陷的严重程度。这为进一步解释反应抑制如何影响ADHD注意缺陷提供神经层面的证据。总之, 反应抑制不足所带来的行为抑制能力差以及相关的注意网络受损可以更好地解释ADHD儿童存在的注意难以维持、不集中等问题。

然而, 值得注意的是, 目前研究仅以“抑制”或“反应抑制”等概念统一代表抑制控制, 尚未区分反应抑制和冲突控制(干扰抑制)在抑制能力中的不同, 这对于解释ADHD儿童抑制控制缺陷具体如何影响核心症状是不够全面的, 也不够精确。冲突控制(干扰抑制)作为认知层面的主动控制能力, 在处理大脑中不合理信息, 尤其是战胜认知冲突中起到重要作用。部分研究表明ADHD儿童具有较弱的冲突控制能力, 这使得他们在面对潜意识或有意识诱发的认知冲突时无法维持和保护任务目标免受干扰(Borella et al., 2013; Mueller et al., 2017)。换言之, 由于缺乏对认知冲突的控制能力, ADHD儿童在执行任务中更容易受到内在分心想法的干扰, 难以维持注意力。冲突控制主要激活的脑区包括背侧前扣带回、背外侧前额叶、顶叶区以及背外侧额叶控制系统(Hung et al., 2018)。其中, 背外侧前额叶主要参与维持和操纵任务相关信息的过程, 背侧前扣带回则在调节行为适应和持续性中发挥着更大的作用(Kolling et al., 2016; Sheth et al., 2012)。因此, 冲突控制可能也是维持注意持续性的关键因素。鉴于冲突控制在抑制能力中的独特作用, 对冲突控制不足如何影响ADHD儿童注意缺陷核心症状的探讨应得到更多关注。未来研究应区分抑制控制的不同类型, 对ADHD儿童注意缺陷中的不同抑制能力受损进行更细致的探讨。

(3)认知灵活性影响ADHD注意缺陷核心症状

认知灵活性又称为转换(shifting), 指的是快速有效地在不同心理情景之间来回转换的能力(Diamond, 2013)。认知灵活性本质上体现个体抑制控制和认知转移的能力, 抑制占优势地位的无效线索, 高效地重新配置资源, 参与儿童注意转移能力的发展(Dajani & Uddin, 2015; Filippetti & Krumm, 2020)。作为执行功能的核心成分之一, ADHD儿童存在认知灵活性缺陷, 并且在认知灵活性任务中, 伴有左侧额下回、前额叶、双侧前脑岛的激活降低(Roshani et al., 2020; Rubia et al., 2010)。在汇总ADHD受损的认知领域时, 研究者将认知灵活性划分到与注意缺陷受损相关的认知领域中, 并提出认知灵活性缺陷可能导致ADHD患者目标选择与认知控制受损, 进而出现注意缺陷的核心症状(Mueller et al., 2017)。Luna- Rodriguez等人(2018)探讨了ADHD患者在转换任务下的注意转移能力, 结果发现转换成本的增加可能会导致ADHD在任务中对不同刺激的注意转移与分配不足。但目前关于认知灵活性和ADHD儿童注意缺陷核心症状之间关系的实证研究比较有限。从定义来看, 认知灵活性更多指的是根据任务需求灵活转换认知模式的能力, 若发展不足, 个体很难从一项任务转移到另一项任务中, 注意转移的有效性受到挑战, 表现出注意难以分配与转移等问题行为(Wendt et al., 2018)。因此, ADHD儿童认知灵活性缺陷可通过影响注意的转移与分配, 进而影响其注意缺陷核心症状的出现。此外, 考虑到认知灵活性建立在工作记忆和抑制控制发展的基础上, 采用更敏感的工具或范式评估认知灵活性, 并将其与其他执行功能成分区分开, 对于解释认知灵活性如何影响注意缺陷十分重要。

(4)从因果操纵视角验证“冷”执行功能影响ADHD核心症状的作用机制

前文分别从认知和神经两条主线初步阐释了“冷”执行功能如何影响ADHD儿童注意缺陷的核心症状, 但缺乏因果操纵的视角来支持和完善其作用机制。下面将从认知干预和神经调控的因果(或近因果)视角, 进一步提供实证证据来验证“冷”执行功能影响注意缺陷核心症状的具体作用机制。

认知干预主要是通过直接训练“冷”执行功能的不同成分, 以提高ADHD儿童的注意表现。其中, 工作记忆训练已被证实是改善ADHD儿童注意缺陷和学业困难的一个很有潜力的干预措施(Kofler, Wells et al., 2020; Wiest et al., 2022)。CET (Central executive training, 中央执行训练)是一种针对ADHD儿童工作记忆缺陷各成分的计算机干预训练, 研究发现CET训练不仅能够显著提高个体工作记忆和抑制控制得分, 还能持久改善个体学习成绩。进一步分析发现, 学习成绩的改善主要是通过提高课堂中的注意行为来实现的(Kofler, Sarver et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2022)。研究者还采用CWMT (Central working memory training, 中央工作记忆训练)对ADHD儿童的工作记忆进行干预训练, 结果发现, 接受CWMT训练的ADHD表现出工作记忆的改善, 注意持续性和选择性的提升, 以及学习成绩的提高(Ackermann et al., 2018; Gray et al., 2012)。此外, 抑制控制和认知灵活性相关的执行功能训练也能显著提升ADHD的注意表现。例如, Kofler等人(2020)对8~12岁的ADHD儿童展开基于Go/No-Go计算机化的认知训练, 持续4周后发现ADHD儿童注意能力在干预后得到持续改善。AKL-T01 (Akili Interactive Labs-T01)是一种基于游戏界面的自适应数字化干预程序, 主要由抑制控制、认知灵活性任务两种任务形式改编, 并且ADHD儿童通过4周AKL-T10的认知干预后, 家长报告和客观行为指标的注意力均得到显著提高(N. Davis et al., 2018; Kollins et al., 2020)。总之, 认知干预通过操纵工作记忆、抑制控制和认知灵活性等不同执行功能成分, 并考察干预前后ADHD儿童注意能力的变化, 从而提供了因果(或近因果)的证据来支持并验证“冷”执行功能对ADHD儿童注意缺陷核心症状影响的作用机理。

神经调控则是通过刺激与“冷”执行功能相关的背外侧前额叶(dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, DLPFC)区域来调节皮层兴奋性, 使大脑功能发生改变, 进而提高ADHD患者的执行功能和改善其注意缺陷核心症状。最新一项大规模的随机双盲实验发现, 采用经颅直流电刺激(transcranial direct current stimulation, tDCS)阳极刺激右侧DLPFC和阴极刺激左侧DLPFC, 持续4周以上可显著改善ADHD成人注意不集中的症状(Leffa et al., 2022)。Nejati等人(2021)单次阳极刺激9~10岁ADHD儿童的右侧DLPFC, 并在刺激前后完成Flanker、Go/No-Go等任务, 结果发现激活右侧DLPFC有助于改善抑制控制能力, 且刺激效果与ADHD的严重程度呈正相关(Nejati et al., 2021)。此外, 一项对62名ADHD成人进行为期3周(共15次)的经颅磁刺激(Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, TMS)研究发现, 刺激右侧PFC能够显著改善个体注意不集中和工作记忆, 且干预后个体在工作记忆任务下的注意力相关脑区的激活增强。也就是说, 刺激右侧PFC能够增强注意相关脑区活动以及改善注意行为表现(Bleich-Cohen et al., 2021)。此外, 研究还发现持续6周对7~12岁ADHD儿童的右侧DLPFC施加高频刺激后, 有助于改善其注意缺陷和多动冲动核心症状(Cao et al., 2019)。综上所述, 采用神经调控技术刺激ADHD患者的DLPFC等区域, 能够提高其“冷”执行功能的任务表现, 进而有效改善注意缺陷的临床症状。这进一步从因果操纵的视角为执行功能缺陷影响注意缺陷的作用机制提供神经层面上的证据。目前神经调控技术应用于治疗ADHD患者正处于快速发展阶段, 但其刺激脑区部位、治疗参数(频率/强度)及刺激时间仍没有统一标准, 临床效果存在很大的差异(Westwood et al., 2021)。大多数研究已发现神经调控技术刺激DLPFC对ADHD患者“冷”执行功能的显著影响, 但对于“冷”执行功能的提高又如何改善其注意缺陷的关注仍较少。值得注意的是, TMS或tDCS还可以通过直接刺激结构或功能连接的核心节点脑区引起“下游”区域的神经活动变化, 包括皮质和皮下脑网络功能连接(Sydnor et al., 2022)。也就是说, 刺激个体的DLPFC, 还会不同程度地激活或抑制其他大脑皮质或皮下脑网络, 共同影响个体的行为表现。从这个视角出发可进一步揭示刺激“冷”执行功能相关脑区进而改善个体注意力的认知神经机制。

4.2 “热”执行功能各子成分缺陷影响ADHD多动冲动核心症状的作用机制

“热”执行功能指个体在高度情感或动机卷入下进行灵活评估和风险决策的能力, 包括延迟满足、奖赏加工和情感调节等。若“热”执行功能存在缺陷, 则导致个体在情感或社会背景下的行为控制失败和动机失调, 具体表现在厌恶延迟、追求及时奖赏、动机失调等方面上。研究者逐渐认识到“热”执行功能缺陷可能是ADHD儿童多动冲动核心症状的主导因素。下面将具体讨论“热”执行功能不同子成分的异常如何影响ADHD儿童多动冲动的核心症状。

(1)延迟满足影响ADHD多动冲动核心症状

延迟满足能力是指一种甘愿为更有价值的长远目标而主动放弃即时满足的抉择取向, 以及在等待过程中展示出自我控制的能力(Mischel et al., 1989)。从时间维度来看, 延迟满足至少包括“做出选择”并“坚持选择”两个阶段(任天虹等, 2015)。前者涉及到个体对所面临的选项进行价值评估、做出选择的过程, 后者则涉及到抵制诱惑、对意图行为的执行过程。著名的“棉花糖实验”用来测量儿童的延迟满足能力(Mischel et al., 1989)。在这类实验中, 儿童可以选择立即得到奖励(如棉花糖), 也可以选择等待一段时间以获得双倍奖励。延迟满足能力可以帮助儿童对眼前利益和未来利益之间进行左右权衡, 做出最有利的选择, 并在选择之后, 坚持行为与选择保持一致, 以期获得最大的利益。ADHD儿童表现出较差的延迟满足能力, 而这种能力缺陷往往被认为与其冲动性的异常行为表现密切相关(Sonuga-Barke et al., 2010; van Dessel et al., 2019)。结合延迟满足的两个阶段来看, ADHD儿童在“做出选择”阶段, 往往对未来利益赋予较低的价值, 对于等待时间表现出明显的厌恶情绪, 做出更冲动、不计后果的选择; 即使做了有利的选择, ADHD儿童在“坚持选择”阶段, 常常不能抵制眼前诱惑, 行为抑制失败, 出现“中途反悔”等冲动行为。延迟满足在日常生活中比比皆是, 如排队等待、先写作业后玩耍等等, 然而由于ADHD儿童延迟满足能力的不足, 使得他们在日常情景中表现出难以等待、厌恶延迟等冲动选择的行为表现(Utsumi et al., 2016; van Dessel et al., 2019)。

已有相关证据支持上述观点。一项汇总22项研究的元分析发现, 在延迟折扣任务中, ADHD儿童和青少年总体表现出较高的延迟折扣(Patros et al., 2016), ADHD儿童更倾向于选择立即满足, 表现出更强的冲动性行为(Martinelli et al., 2017)。此外, 研究者发现在延迟等待过程中ADHD往往体验到更多的主观负面情绪, 具有明显的厌恶延迟(Rosch & Mostofsky, 2016)。神经影像的研究进一步发现, 延迟厌恶表现为与负面情绪处理加工相关的脑区(如杏仁核)的过度激活相关, 随着延迟时间增长反应更强烈(van Dessel et al., 2018; van Dessel et al., 2020)。除杏仁核过度激活之外, ADHD儿童在等待期间还表现出过度的自发神经活动(低频振荡), 且这种过度活动与冲动决策的行为特征相关(Hsu et al., 2015)。在延迟满足的“坚持”阶段更多体现的是个体对有目标行为进行自我控制的能力, 这涉及到背外侧前额叶、腹外侧前额叶和后侧顶叶等脑区的参与, 而这些脑区也与冲动性行为有关(Dalley & Ersche, 2019)。ADHD儿童自我控制的失败, 不仅影响其能否坚持下去, 还会带来更多外化的问题行为。总之, 较差的延迟满足能力导致ADHD儿童在“做出选择”阶段倾向于立即满足, 且厌恶延迟; 在“坚持选择”阶段无法抑制当下诱惑带来的冲突, 行为控制失败。这两者共同作用, 影响ADHD冲动性行为的出现。

(2)奖赏加工影响ADHD多动冲动核心症状

越来越多研究者认为, 奖赏加工异常也是影响ADHD儿童多动冲动核心症状的重要因素之一(Bunford et al., 2022; Kallweit et al., 2021; Tegelbeckers et al., 2018)。奖赏加工可以分为两个阶段:奖赏预期阶段和结果反应阶段(Rademacher et al., 2010)。一方面, 奖赏预期是指个体对将要来临的、可能获得的奖赏持有的一种等待和渴望状态。在生活中, 一旦个体注意到可产生奖赏的刺激线索, 即会赋予刺激更高的预期结果价值以及促使目标导向行为的出现。个体冲动性行为的出现往往受到强烈的奖赏预期所驱动, 这类个体具有较高奖赏敏感性(Dawe et al., 2004; 熊素红, 孙洪杰, 2017)。尤其是, ADHD儿童对某些刺激(如金钱等)的奖赏敏感性更高(Fosco et al., 2015; Tripp & Wickens, 2012), 在面对这类奖赏预期时, 个体更容易忽视威胁线索和不利后果, 无法抑制由奖赏预期造成的驱动, 而产生冲动性行为。另一方面, 结果反应阶段是指对已获得的奖赏进行评价、并监控行为是否达到任务目标的过程。在这个阶段, 个体根据感知到的奖赏反馈来建立对奖赏线索的行为联结(杨玲等, 2015)。但ADHD儿童对奖赏结果的反应往往存在异常。例如, ADHD患者认为金钱、权利等具有“凸显性”的奖赏物拥有更高的价值, 反而对其他“回报”较低的奖赏物(如笑脸、美景等)失去兴趣(Demurie et al., 2011; Gonzalez-Gadea et al., 2016)。这种奖赏反应的失调使个体依赖于“畸形”奖赏联结, 一旦“凸显性”的奖赏线索出现, ADHD则表现出更急迫的寻求反应(即冲动性)。久而久之, 大多数的奖赏反应都被弱化, 只有“更高价值”的奖赏刺激才能产生足够的信号。如果不加以干预, 这种奖赏异常的加工机制会导致ADHD个体不断追求更刺激的冒险活动(如飙车、赌博等), 同时也是物质滥用和成瘾过程发展和维持的关键 (Grimm et al., 2021)。因此, ADHD儿童常常表现出奖赏预期驱动的动机失调和奖赏线索−行为的联结失败, 使得儿童不断寻求更频繁的外在刺激, 这也可以用来解释为什么ADHD儿童比同龄人更多动、冲动。

目前大量研究表明, ADHD的奖赏加工存在异常具有神经学的基础, 即大脑奖赏环路的结构与功能异常(von Rhein et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018)。先前研究较为一致的发现, 在金钱奖赏加工任务中, ADHD患者在奖赏预期过程的腹侧纹状体(Ventral struatum)激活不足(Plichta & Scheres, 2014; Scheres et al., 2007; van Hulst et al., 2017), 且这种对奖赏线索的预期降低, 导致ADHD更倾向于选择立即奖赏。研究还发现ADHD患者的眶额叶在奖赏预期中过度激活, 且激活程度与ADHD多动冲动核心症状呈显著正相关。进而推测出, 由于眶额叶过度激活导致ADHD个体无法正确编码预期的结果价值, 从而出现更多的非适应性行为(Tegelbeckers et al., 2018)。此外, ADHD儿童的奖赏异常最常见的是延迟折扣的增加, 即倾向于选择较小的即时奖赏, 而非大的延迟奖赏(Jackson & MacKillop, 2016; Marx et al., 2021; Yu & Sonuga-Barke, 2020)。在延迟折扣任务下, 研究发现ADHD儿童奖赏网络与额顶网络之间的功能连接异常(失衡), 这种不平衡会影响冲动行为的出现, 可能也是ADHD儿童多动冲动核心症状背后的神经机制(Dias et al., 2015)。ADHD对延迟奖赏还会表现出强烈的负性情绪, 较高的延迟折扣与延迟厌恶(负性情绪)共同作用, 加剧了个体的冲动行为表现(van Dessel et al., 2018)。基于上述认知和神经的证据, 可以推断出奖赏加工的异常主要通过较高的奖赏预期驱动和失调的奖赏结果反应, 进而影响 ADHD 个体的多动冲动水平。

(3)情绪失调影响ADHD多动冲动核心症状

情绪失调在ADHD儿童的日常生活中普遍且持续存在着, 且被视为重要的临床特征和潜在的治疗目标(Barkley, 2015; Graziano & Garcia, 2016)。Faraone等人(2019)在专家共识中明确提出, ADHD的情绪失调主要表现在情绪冲动(emotional impulsivity, EI)和情绪调节困难(deficient emotional self-regulation, DESR)两个方面。其中, 情绪冲动性是指个体面对情绪刺激表现出异常高的反应性, 这导致对刺激的情绪反应快速上升, 达到受损水平; 情绪调节困难则指由于难以管理情绪体验, 控制行为表现, 导致激活的异常情绪反应回到基线水平的速度明显变慢(Barkley, 2015; Faraone et al., 2019)。一些研究者将情绪失调看作是ADHD的核心症状和功能损害, 但作为“热”执行功能的一部分, 情绪失调更可能影响ADHD儿童多动冲动行为的出现。具体来看, ADHD儿童具有强烈的情绪反应性, 常常表现为易怒、易产生消极情绪等现象(Colonna et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019)。值得注意的是, 在面对情绪刺激时, 除表现出较强的情绪冲动性之外, ADHD个体的生理唤醒出现大幅度持续上升。测量自主神经指标的研究发现, ADHD儿童在负性情绪诱发状态下表现出更大的交感神经失调(即皮电指数增强), 情绪调节过程中存在更大的副交感神经失调(即呼吸窦性心律失常增强) (Morris et al., 2020; Musser et al., 2011)。这种情绪迅速变化的过程中可能存在更多的能量积累, 不仅出现更多的冲动性行为, 还需要“更多的行为”发泄多余的能量。情绪反应最直观的行为表现即为冲动行为, 目前研究往往将情绪反应和冲动行为看作一体或混为一谈(Faraone et al., 2019), 尚未详细探讨情绪反应尤其是情绪高冲动性具体如何影响ADHD多动冲动核心症状的出现。同时, 生理指标能够为ADHD儿童的情绪反应提供更可靠、生态的数据, 可应用于未来研究以探究情绪失调与ADHD儿童多动冲动的关系及作用机制。

ADHD的情绪调节困难被认为是由杏仁核、腹侧纹状体和眶额叶皮质功能异常引起的, 并自下而上影响其他认知加工过程(Christiansen et al., 2019; Shaw et al., 2014)。例如, 情绪调节困难使得ADHD个体在面对延迟奖励时难以调节延迟带来的负面情绪, 还会放大情绪体验, 进而表现得更冲动。Lugo-Candelas等人(2017)还发现ADHD儿童在情绪背景下对注意力的分配和认知控制方面不如同龄人有效, 情绪调节的失败可能会加剧ADHD儿童的注意缺陷和多动冲动的核心症状表现。因此, 情绪失调的ADHD儿童通常表现出较高的情绪反应和较差的情绪调节能力, 这使得他们在日常生活中或面对情绪事件时更容易出现非适应行为。较为重要的是, 情绪失调更多存在于日常生活中, 实验室诱发的情绪反应和调节具有片面性。已有研究者采用生态瞬时评估法捕捉ADHD儿童在日常生活中的情绪波动变化, 发现ADHD儿童具有更高的情绪变异性(即情绪波动且强烈), 并且这种变异性带来更严重的功能损害(Rosen et al., 2015; Walerius et al., 2018)。但目前仍缺少从生态视角探究ADHD儿童自发的情绪波动状态与核心症状之间动态关系的研究。

(4)从因果操纵视角验证“热”执行功能影响ADHD核心症状的作用机制

前文已提到对于影响ADHD儿童多动、冲动核心症状出现的“热”执行功能缺陷, 主要有以下解释:(a)与自我控制的延迟满足能力较差, 导致儿童倾向于立即满足并难以坚持等待; (b)由大脑奖赏网络异常激活导致的奖赏加工异常, 并带来的动机失调和线索−行为联结失败; (c)情绪失调表现出的情绪冲动性和情绪调节困难所产生的负面影响。下面从因果(或近因果)操纵的视角进一步提供实证证据来支持和验证“热”执行功能影响多动冲动缺陷核心症状的具体作用机制。

近年来, 正念练习被认为是一种训练“热”执行功能的有效方式, 主要强调个体以不评判的态度对当下身心状态进行有意识的体验与觉知(Kabat-Zinn, 1994)。正念结合了专注训练(如将注意力放下)和情绪调节训练(如认知、重新评价、接纳消极情绪等), 通过降低个体的压力和负性情绪觉知水平, 以及促进良性奖赏机制的重塑, 来提高个体的“热”执行功能(J. Davis et al., 2018; Garland, 2021; Tang et al., 2015)。更本质的是, 经过正念训练可以显著改善个体的冲动性行为, 其作用机制也是降低个体由情绪或动机卷入带来的冲动驱力, 进而增强自我控制能力(杨珍芝, 曾红, 2023)。此外, 正念训练还可以提高觉察和专注水平, 通过自上而下的控制系统和情绪调节, 减弱个体动作冲动性(即不合时宜或无益外显的动作行为) (Franco et al., 2016; Ron-Grajales et al., 2021)。可得出结论, 经过正念训练可以改善与“热”执行功能相关的能力水平, 进而有助于降低ADHD患者的多动、冲动行为。一项元分析系统回顾了正念训练对ADHD 的干预效果, 结果发现以正念为基础的干预训练能够显著降低ADHD个体的多动冲动等临床症状, 同时对注意缺陷的改善也比较明显(Cairncross & Miller, 2020)。研究者对11~15岁的ADHD儿童及其父母进行为期八周的正念干预后发现, 父母评估的儿童多动、冲动水平显著下降, 且效果持续至少八周(van der Oord et al., 2012)。针对ADHD成人的干预研究也发现, 正念冥想能够改善个体的情绪调节策略和冲动控制水平(Mitchell et al., 2017)。值得注意的是, 正念训练还能够引起大脑激活模式变化和功能改变(Tang et al., 2015)。例如, 正念训练使得个体在进行负性情绪图片加工时杏仁核激活程度减弱, 但杏仁核与腹内侧额叶皮层之间的功能连接增强, 这意味着情绪唤醒降低且情绪控制能力增强(Kral et al., 2018); 经过正念训练后, 个体在面对成瘾奖赏线索时参与奖赏预期加工的大脑区域激活也显著减弱(Kirk et al., 2019), 降低个体的冲动选择。上述神经影像的证据表明, 正念训练可通过改善与“热”执行功能相关的脑区激活和功能连接异常, 进而改善个体多动、冲动的异常行为水平。这为验证“热”执行功能影响ADHD多动、冲动核心症状提供了近因果操纵的实验证据。

眶额叶(orbitofrontal cortex, OFC)是“热”执行功能的重要脑区, 由于位于大脑皮层区域, 往往被看作是情绪调节、风险决策等神经调控刺激的关键靶点之一。眶额叶参与复杂的决策过程, 如奖赏加工和风险感知等, 并在负性情绪调节中起到重要作用(Ernst et al., 2002; Stalnaker et al., 2015)。部分研究者采用tDCS或TMS技术对OFC进行神经调控后发现, 刺激OFC可改善个体的情绪体验与风险决策行为(Howard et al., 2020; Ouellet et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017)。一项研究对24名正常个体的DLPFC和OFC进行tDCS单次刺激, 结果发现刺激OFC显著降低了个体的冒险行为和风险决策, 即改善了个体的“热”执行功能(Nejati et al., 2018)。尽管OFC在ADHD患者的“热”执行功能缺陷中起到重要作用, 但目前针对OFC进行神经调控的研究仍较有限。一项采用tDCS阴极刺激DLPFC和阳极刺激OFC的研究发现, 刺激后对ADHD儿童认知灵活性的改善效果最明显(Nejati et al., 2020)。该研究尚未直接探讨刺激OFC是否能够改善ADHD儿童的“热”执行功能表现, 更没有考虑刺激OFC对ADHD多动冲动核心症状的影响。基于已有研究和理论基础可以推测, 刺激ADHD患者的OFC等“热”执行功能相关的脑区, 不仅能够提高其“热”执行功能的任务表现, 还能有效改善多动、冲动的临床症状。此外, “热”执行功能相关脑区位于腹内侧区域, 且与边缘系统、奖赏网络连接密切, 但“热”执行功能缺陷如何通过脑网络和功能连接异常进而影响ADHD儿童异常行为表现的目前仍不清楚。考虑到神经调控技术可以通过刺激皮层的结构和功能连接引起大脑其他区域或脑网络的变化, 未来研究可进一步采用神经调控技术操纵“热”执行功能, 为影响ADHD多动冲动核心症状的作用机制提供神经层面的因果证据。

4.3 “冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD核心症状的交互影响

随着执行功能研究的深入, 近年来逐渐呈现出对“冷”和“热”执行功能之间相互性的关注趋势(Zelazo, 2020)。研究者发现“冷”和“热”执行功能不是独立存在的, 两者之间存在自上而下(皮质−边缘)和自下而上(边缘−皮质)的动态交互作用(Moriguchi, 2021; Nejati et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018)。一方面, “冷”执行功能可以调节个体在面对奖赏预期时对奖赏的感知价值, 还可以在结果反馈阶段控制个体的情绪反应以及建立正确的行为联结, 起到自上而下认知控制的关键作用(Kryza-Lacombe et al., 2022; Luna, 2009)。例如, 更强的“冷”执行功能可以保护儿童青少年在充满诱惑和威胁的环境中, 控制情绪反应和动机驱动, 做出正确选择, 减少环境带来的伤害。另一方面, “热”执行功能参与价值评估与风险决策, 这直接影响以目标为导向的“冷”执行功能表现, 起到自下而上情绪诱发的作用。“热”执行功能发展较好, 可以帮助个体合理价值评估, 规避风险, 增强自我控制能力。例如, 儿童青少年在奖励和动机驱动背景下, “冷”执行功能任务表现得更好(Ma et al., 2016)。可见, 个体某些行为的出现是“冷”执行功能和“热”执行功能交互协调的结果。

然而, ADHD儿童在 “冷”和“热”执行功能上均呈现出异常, 可能存在交互作用共同影响核心症状的出现。从行为表现来看, “热”执行功能缺陷所带来的奖赏异常、情绪失调等, 是ADHD儿童冲动、多动等异常行为得以发生和持续的重要因素。但这种缺陷是否能直接引发冲动、多动行为, 还要取决于“冷”执行功能的参与。也就是说, ADHD儿童“冷”执行功能存在不足, 使其无法控制“热”执行功能缺陷带来的异常情绪反应和不合理的奖赏预期(动机倾向), 因此出现更多的冲动、多动行为。例如, ADHD儿童本身延迟满足能力较差, 更倾向于立即满足, 若加上抑制控制不足, 则无法抵制当下诱惑带来的冲突, 表现出更冲动的行为, 而这往往也是日常生活中常常出现的场景。此外, 注意控制过程需要“冷”执行功能参与和消耗大量的认知资源, 而由于“热”执行功能发展的不足, ADHD儿童更容易受到自动化情绪因素的强大驱动, 这会使得个体的注意力更容易转移到外界刺激。即使个体的“冷”执行功能发展良好, 若“热”执行功能存在缺陷, 个体仍难以控制强大的情绪驱动力量, 以及难以抑制自动化的加工, 因而注意控制出现问题。例如, 在需要注意集中的情景(课堂)下, ADHD儿童不仅由于“冷”执行功能缺陷导致其注意力难以集中, 还可能因为“热”执行功能缺陷更容易受到动机或情绪等线索的驱动, 难以抵抗有诱惑的分心物, 注意受到干扰。从神经基础的角度来看, “冷”和“热”执行功能相关脑区间的发展不平衡或受损也可能导致ADHD儿童核心症状等异常行为的出现。例如, 用来解释个体冲动性的双系统理论(The Dual Systems Model)指出, 大脑认知控制系统(以背外侧前额叶、前扣带回为主)和社会情绪系统(以眶额叶、杏仁核为主)之间发展的不失衡导致会导致青少年冲动性行为的发生(Shulman et al., 2016; Steinberg et al., 2008)。而ADHD患者在上述两个系统中均表现出不足(Capri et al., 2020), 并且研究也发现ADHD儿童前额叶皮层与杏仁核或纹状体网络之间存在不平衡的异常功能连接, 这可能是ADHD 非适应性行为和冲动性出现的原因(Dias et al., 2015)。

总之, ADHD儿童“冷”和“热”执行功能之间的交互作用共同影响注意缺陷、多动冲动核心症状的出现。具体而言, “冷”执行功能缺陷不仅直接影响ADHD儿童注意加工过程, 自上而下的“失控”还使得个体难以控制情绪反应和抑制不合理行为, 从而表现出更多的冲动、多动行为; 而“热”执行功能缺陷不仅导致动机失调和奖赏异常, 自下而上的“失调”还会带来更多的错误目标导向和自动化加工, 进而影响个体的注意加工过程。

5 未来研究展望

ADHD是一种神经发育障碍, 与前额叶异常相关的执行功能缺陷可能是导致ADHD儿童核心症状背后的认知机制。尽管这一问题得到研究者的广泛关注, 但现阶段尚未真正探明执行功能缺陷为何以及如何影响ADHD核心症状产生的机制。本文在已有理论和实证研究基础上, 基于神经−认知−行为的发展途径解释了为什么“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷能够影响ADHD不同核心症状, 并试图搭建ADHD儿童神经发育异常与其核心症状之间的认知缺陷桥梁。此外, 还提出“冷”、“热”执行功能可能是导致ADHD不同核心症状的两条认知途径, 其中“冷”执行功能是注意缺陷核心症状的主导因素, “热”执行功能是多动冲动核心症状的主导因素。更重要的是, 本文重点阐述了“冷”、“热”执行功能各子成分缺陷影响ADHD不同核心症状的作用机制及具体途径, 为探究导致ADHD核心症状的认知神经机制提供了研究思路。但目前仍有有一些问题亟待考察, 未来研究可以进一步考察以下四个方面:

首先, “冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷影响ADHD不同核心症状的作用机制理论有待进一步检验和完善。以往对ADHD儿童的发病机理尚不明了, 基于“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷视角探究导致ADHD不同核心症状的认知神经机制, 使得从认知层面上阐释ADHD发病机理成为可能。尽管先前研究在执行功能缺陷和ADHD核心症状之间的相关性进行了一些探索, 但目前仍缺乏一个整合性的理论模型解释执行功能缺陷影响ADHD不同核心症状的认知神经机制。前文系统探讨了“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD不同核心症状的影响及其可能存在的认知机制, 其机制的有效性仍有待实证研究的支持。以认知机制来看, ADHD注意缺陷, 多动冲动核心症状的产生主要是由于执行功能发展缺陷或不足所导致的, 并且“冷”“热”执行功能的各个子成分在影响ADHD核心症状的途径中具有独特且重要的作用。因此, 未来研究应将执行功能缺陷纳入到ADHD大规模流行病调查中去, 系统探讨“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对不同ADHD亚型的影响比重如何, 以及执行功能各子成分对注意缺陷、多动冲动不同核心症状的解释率多少, 并在此基础上构建影响ADHD核心症状的执行功能缺陷认知模型, 为ADHD儿童早期筛查与诊断提供科学标准。此外, 从儿童发展角度考察执行功能发展变化对ADHD核心症状的影响也是非常重要。现有的横断研究难以解释ADHD核心症状的出现或随年龄改善是否与执行功能的发展相关, 尤其是“冷”、“热”执行功能在儿童时期的发展轨迹不同, 可能给ADHD核心症状带来不同的影响(O'Toole et al., 2018)。因此, 未来研究还可以结合纵向追踪设计揭示执行功能的发展变化是否能够预测或影响ADHD儿童核心症状的严重程度, 从发展视角检验和完善执行功能缺陷影响ADHD核心症状的认知机制。

再次, 进一步探明“冷”、“热”执行功能影响ADHD核心症状的神经基础和认知神经机制。从神经层面来看, ADHD儿童核心症状主要与前额叶皮层的结构和功能异常变化密切相关, 但这种异常神经基础背后的认知缺陷及其作用机制目前正处于探索阶段。与“冷”、“热”执行功能相关的脑区的结构变化或功能连接是否与ADHD核心症状存在关联, 以及相关的异常神经基础是否能预测ADHD核心症状的严重程度仍有待去解决。值得关注的是, 前额叶并不是独立工作的, 它与皮下组织结构以及其他脑网络之间存在着密切的功能连接。例如, 前额叶皮层的锥体神经元将信号投射到纹状体, 然后再到丘脑, 最后再次返回到皮层, 形成皮层−纹状体−丘脑−皮层的环路结构, 发挥整体功能(Jiang et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2016)。因此, 以前额叶皮层为主的神经环路结构异常可能为理解执行功能缺陷对ADHD不同核心症状的影响搭建桥梁(Zhu et al., 2018)。此外, “冷”、“热”执行功能所涉及的相关脑区, 同时也是注意网络和奖赏网络等神经网络的核心节点。若上述脑区存在不足, 不仅使得执行功能发展受限, 还会通过功能连接引起相关脑网络的激活异常, 两者共同作用于ADHD核心症状的出现。未来研究可以进一步探索在不同执行功能任务下ADHD儿童激活的特异脑区以及与其他脑网络之间的功能连接是否异常, 力图探明“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷影响ADHD不同核心症状的神经基础和神经网络模型。同时, 领域内关于ADHD神经基础的研究大都基于记录和关联视角, 缺乏因果(或近因果)操纵的实证证据来支持“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD不同核心症状产生的影响及其认知神经机制。鉴于神经调控技术可以通过刺激皮层引起“下游”脑结构和网络功能连接的间接变化, 未来研究也可将神经调控技术结合到脑影像的研究中, 从因果操纵的视角验证执行功能缺陷影响ADHD核心症状的认知神经模型。

再次, 从生态层面考察“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD儿童核心症状的影响。研究发现ADHD儿童执行功能缺陷存在明显的个体异质性(Bunger et al., 2021; Kofler et al., 2019)。具体来看, ADHD儿童的执行功能得分在基于任务的实验室测试和父母/教师量表评分上存在显著的结果差异, 仅有约52%的ADHD儿童在实验室任务上显示有执行功能缺陷, 而父母/教师则报告有超过90%的ADHD儿童具有执行功能缺陷(Sjöwall & Thorell, 2019)。并且临床医生进行诊断时更多地依赖于父母/教师报告的量表得分, 因为它更多反映了ADHD儿童在生活中的临床表现(DSM-IV, 2013)。这也说明目前实验室任务的生态效度不足, 很难真实反映个体在日常生活中的异常表现(Barkley & Murphy, 2011; Bunger et al., 2021)。尤其是现有实验室任务大多集中于“冷”执行功能, 较少关注大量情绪或动机卷入下的“热”执行功能是如何影响ADHD核心症状出现的。同时, 日常生活中动机和情绪等驱动线索随处可见, 不仅需要“热”执行功能的参与, 更多涉及到“冷”和“热”执行功能之间的相互作用(Zelazo, 2020)。如难以对抗分心物是ADHD经历了抑制控制与诱惑驱动之间斗争的结果, 当具有诱惑力的分心物战胜了控制能力, 个体才会打断注意持续性, 表现出注意力不集中。也就是说, 即使个体“冷”执行功能发展良好, 若“热”执行功能存在不足, 动机驱动力量过大, 异常的行为表现也是难以避免的(杨珍芝, 曾红, 2023)。然而ADHD儿童“冷”、“热”执行功能均存在异常, 两者交互将促使ADHD儿童在日常生活中表现出更多执行功能缺陷相关的异常行为表现。现有研究很大程度忽略了上述观点, 较为片面地看待ADHD儿童执行功能缺陷及其与核心症状之间的关系。因此, 未来研究应从生态视角探讨ADHD儿童“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷之间的交互作用如何影响日常生活中核心症状的出现, 并试图回答ADHD儿童执行功能缺陷存在个体异质性的问题。

最后, 基于“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷, 开发对ADHD儿童核心症状具有长效作用的心理干预和神经调控方案。理论上, 针对执行功能缺陷的干预具有十分重要的临床价值, 不仅会改善ADHD核心症状和社会功能, 还可能存在持久的改善效果(Karr et al., 2018)。但目前现有的执行功能干预方案对ADHD相关核心症状的改善效果并不显著, 或者难以使ADHD儿童的问题行为“正常化”。这种低效性的原因可能是这些干预目标只关注能力本身, 而没有考虑执行功能各子成分缺陷与ADHD异常行为表现之间的关系如何, 使得干预的远迁移效果大大下降(Kofler, Wells et al., 2020)。前文所提出的认知神经机制已明确“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷对ADHD不同核心症状的影响, 并提示未来研究可以从认知干预入手, 通过操纵ADHD儿童的“冷”执行功能以改善注意缺陷的核心症状, 或者训练“热”执行功能相关的能力以减少ADHD儿童多动冲动的症状表现。同时, 未来研究还可以采用神经调控技术, 探究单次或多次TMS/tDCS刺激DLPFC是否通过提高“冷”执行功能来减少注意不集中等异常行为的出现, 或者刺激OFC等脑区是否能够通过提升“热”执行功能来增加对行为和情绪的控制能力。值得注意的是, ADHD儿童执行功能各子成分缺陷具有很强的个体差异性。以注意不集中的症状表现为例, 一部分ADHD儿童可能是由于工作记忆表征困难, 无法正确选择目标信息所导致的, 另一部分ADHD儿童则与抑制控制不足, 难以对抗外界干扰刺激有关。若不从个体层面进行区分, 干预目标很难与个体能力缺陷和发展水平相匹配, 使得改善其核心症状的有效性和长期性受到很大限制。因此, 在探明ADHD儿童发病机理的基础上, 未来研究应基于“冷”、“热”执行功能缺陷, 从认知干预和神经调控两条主线实现对ADHD儿童核心症状的个性化干预与精准治疗, 力图实现干预效果的远迁移。

李廷玉, 陈立, 李斐, 杨莉, 曹爱华, 张劲松, 邹小兵. (2020). 注意缺陷多动障碍早期识别、规范诊断和治疗的儿科专家共识.,(3), 188−193.

任天虹, 胡志善, 孙红月, 刘扬, 李纾. (2015). 选择与坚持: 跨期选择与延迟满足之比较.,(2), 303−315.

熊素红, 孙洪杰. (2017). 奖赏敏感性在冲动性饮食行为中的作用.,(2), 429−435.

杨玲, 苏波波, 张建勋, 柳斌, 卫晓芸, 赵鑫. (2015). 物质成瘾人群金钱奖赏加工的异常机制及可恢复性.,(9), 1617−1626.

杨珍芝, 曾红. (2023). 正念训练对冲动性不同要素的影响: 基于双加工理论.,(2), 274−287.

张微, 徐精敏, 宋红艳. (2010). 儿童注意缺陷多动障碍(ADHD)的“冷”“热”执行功能.(1), 55−64.

Ackermann, S., Halfon, O., Fornari, E., Urben, S., & Bader, M. (2018). Cognitive Working Memory Training (CWMT) in adolescents suffering from Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A controlled trial taking into account concomitant medication effects.,, 79−85.

Agnew-Blais, J. C., Polanczyk, G. V., Danese, A., Wertz, J., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2016). Evaluation of the persistence, remission, and emergence of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in young adulthood.,(7), 713−720.

Ahmed, L., & de Fockert, J. W. (2012). Working memory load can both improve and impair selective attention: Evidence from the Navon paradigm.,(7), 1397−1405.

Antonini, T. N., Becker, S. P., Tamm, L., & Epstein, J. N. (2015). Hot and cool executive functions in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid oppositional defiant disorder.,(8), 584−595.

Aron, A. R., Robbins, T. W., & Poldrack, R. A. (2004). Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex.,(4), 170−177.

Baddeley, A. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies.(1), 1−29.

Bahmani, Z., Clark, K., Merrikhi, Y., Mueller, A., Pettine, W., Isabel Vanegas, M., … Noudoost, B. (2019). Prefrontal contributions to attention and working memory.(9), 129−153.

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD.,(1), 65−94.

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Emotional dysregulation is a core component of ADHD. In R. A. Barkley (Ed.),(pp. 81−115). The Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2011). The nature of executive function (EF) deficits in daily life activities in adults with ADHD and their relationship to performance on EF tests.,(2), 137−158.

Bleich-Cohen, M., Gurevitch, G., Carmi, N., Medvedovsky, M., Bregman, N., Nevler, N., … Ash, E. L. (2021). A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of prefrontal cortex deep transcranial magnetic stimulation efficacy in adults with attention deficit/hyperactive disorder: A double blind, randomized clinical trial.,(4). e102670

Borella, E., de Ribaupierre, A., Cornoldi, C., & Chicherio, C. (2013). Beyond interference control impairment in ADHD: Evidence from increased intraindividual variability in the color-stroop test.,(5), 495−515.

Bunford, N., Kujawa, A., Dyson, M., Olino, T., & Klein, D. N. (2022). Examination of developmental pathways from preschool temperament to early adolescent ADHD symptoms through initial responsiveness to reward.,(3), 841−853.

Bunger, A., Urfer-Maurer, N., & Grob, A. (2021). Multimethod assessment of attention, executive functions, and motor skills in children with and without ADHD: Children's performance and parents' perceptions.,(4), 596−606.

Cai, W. D., Chen, T. W., Szegletes, L., Supekar, K., & Menon, V. (2018). Aberrant time-varying cross-network interactions in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the relation to attention deficits.,(3), 263−273.

Cai, W. D., Griffiths, K., Korgaonkar, M. S., Williams, L. M., & Menon, V. (2021). Inhibition-related modulation of salience and frontoparietal networks predicts cognitive control ability and inattention symptoms in children with ADHD.,(8), 4016−4025.

Cai, W. D., & Leung, H. C. (2011). Rule-guided executive control of response inhibition: Functional topography of the inferior frontal cortex.,(6), e20840.

Cairncross, M., & Miller, C. J. (2020). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies for ADHD: A meta-analytic review.,(5), 627−643.

Cao, P. F., Wang, L. X., Cheng, Q., Sun, X. J., Kang, Q., Dai, L. B., … Song, Z. X. (2019). Changes in serum miRNA-let-7 level in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder treated by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or atomoxetine: An exploratory trial.,(4), 189−194.

Capri, T., Santoddi, E., & Fabio, R. A. (2020). Multi-source interference task paradigm to enhance automatic and controlled processes in ADHD.,(2), 103542.

Castellanos, F. X., & Aoki, Y. (2016). Intrinsic functional connectivity in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: A science in development.,(3), 253−261.

Christiansen, H., Hirsch, O., Albrecht, B., & Chavanon, M. (2019). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and emotion regulation over the life span.,(3), 1−17.

Colonna, S., Eyre, O., Agha, S. S., Thapar, A., van Goozen, S., & Langley, K. (2022). Investigating the associations between irritability and hot and cool executive functioning in those with ADHD.,(1), 166−176.

Cortese, S., Aoki, Y. Y., Itahashi, T., Castellanos, F. X., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2021). Systematic review and meta- analysis: Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(1), 61−75.

Crone, E. A., & Steinbeis, N. (2017). Neural perspectives on cognitive control development during childhood and adolescence.,(3), 205− 215.

Cubillo, A., Halari, R., Smith, A., Taylor, E., & Rubia, K. (2012). A review of fronto-striatal and fronto-cortical brain abnormalities in children and adults with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder and new evidence for dysfunction in adults with ADHD during motivation and attention.,(2), 194−215.

Dajani, D. R., & Uddin, L. Q. (2015). Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience.,(9), 571−578.

Dalley, J. W., & Ersche, K. D. (2019). Neural circuitry and mechanisms of waiting impulsivity: Relevance to addiction.,(1766), e20180145.

Davis, J. P., Berry, D., Dumas, T. M., Ritter, E., Smith, D. C., Menard, C., & Roberts, B. W. (2018). Substance use outcomes for mindfulness based relapse prevention are partially mediated by reductions in stress: Results from a randomized trial.,(971), 37−48.

Davis, N. O., Bower, J., & Kollins, S. H. (2018). Proof-of-concept study of an at-home, engaging, digital intervention for pediatric ADHD.,(1), e0189749.

Dawe, S., Gullo, M. J., & Loxton, N. J. (2004). Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: Implications for substance misuse.,(7), 1389−1405.

Dekkers, T. J., Popma, A., van Rentergem, J. A. A., Bexkens, A., & Huizenga, H. M. (2016). Risky decision making in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-regression analysis.,(1), 1−16.

Demurie, E., Roeyers, H., Baeyens, D., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2011). Common alterations in sensitivity to type but not amount of reward in ADHD and autism spectrum disorders.,(11), 1164−1173.

DeRonda, A., Zhao, Y., Seymour, K. E., Mostofsky, S. H., & Rosch, K. S. (2021). Distinct patterns of impaired cognitive control among boys and girls with ADHD across development.,(7), 835−848.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions.(17), 135−168.

Dias, T. G. C., Iyer, S. P., Carpenter, S. D., Cary, R. P., Wilson, V. B., Mitchell, S. H., … Fair, D. A. (2015). Characterizing heterogeneity in children with and without ADHD based on reward system connectivity.,(2), 155−174.

Ernst, M., Bolla, K., Mouratidis, M., Contoreggi, C., Matochik, J. A., Kurian, V., … London, E. D. (2002). Decision-making in a risk-taking task: A PET study.,(5), 682−691.

Fabio, R. A., & Urso, M. F. (2014). The analysis of attention network in ADHD, attention problems and typically developing subjects.,(2), 199−221.

Faraone, S. V., Asherson, P., Banaschewski, T., Biederman, J., Buitelaar, J. K., Ramos-Quiroga, J. A., … Franke, B. (2015). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(1), 1−23.

Faraone, S. V., Banaschewski, T., Coghill, D., Zheng, Y., Biederman, J., Bellgrove, M. A., … Wang, Y. (2021). The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder.,(9), 789−818.

Faraone, S. V., Rostain, A. L., Blader, J., Busch, B., Childress, A. C., Connor, D. F., & Newcorn, J. H. (2019). Practitioner review: Emotional dysregulation in attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder--Implications for clinical recognition and intervention.,(2), 133−150.

Filippetti, V. A., & Krumm, G. (2020). A hierarchical model of cognitive flexibility in children: Extending the relationship between flexibility, creativity and academic achievement.,(6), 770−800.

Forte, A., Orri, M., Galera, C., Pompili, M., Turecki, G., Boivin, M., … Côté, S. M. (2019). Developmental trajectories of childhood symptoms of hyperactivity/ inattention and suicidal behavior during adolescence.,(2), 145−151.

Fosco, W. D., Hawk, L. W., Rosch, K. S., & Bubnik, M. G. (2015). Evaluating cognitive and motivational accounts of greater reinforcement effects among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(1), 20.

Fosco, W. D., Kofler, M. J., Alderson, R. M., Tarle, S. J., Raiker, J. S., & Sarver, D. E. (2019). Inhibitory control and information processing in ADHD: Comparing the dual task and performance adjustment hypotheses.,(6), 961−974.

Fosco, W. D., Kofler, M. J., Groves, N. B., Chan, E. S., & Raiker, J. S. (2020). Which ‘working’ components of working memory aren’t working in youth with ADHD?,(5), 647−660.

Franco, C., Amutio, A., López-González, L., Oriol, X., & Martínez-Taboada, C. (2016). Effect of a mindfulness training program on the impulsivity and aggression levels of adolescents with behavioral problems in the classroom.,, 1385−1396.

Franke, B., Michelini, G., Asherson, P., Banaschewski, T., Bilbow, A., Buitelaar, J. K., … Haavik, J. (2018). Live fast, die young? A review on the developmental trajectories of ADHD across the lifespan.,(10), 1059−1088.

Garland, E. L. (2021). Mindful positive emotion regulation as a treatment for addiction: From hedonic pleasure to self-transcendent meaning.,(7), 168−177.

Gazzaley, A., & Nobre, A. C. (2012). Top-down modulation: Bridging selective attention and working memory.,(2), 129−135.

Geurts, H. M., van der Oord, S., & Crone, E. A. (2006). Hot and cool aspects of cognitive control in children with ADHD: Decision-making and inhibition.,(6), 813−824.

Gonzalez-Gadea, M. L., Sigman, M., Rattazzi, A., Lavin, C., Rivera-Rei, A., Marino, J., … Ibanez, A. (2016). Neural markers of social and monetary rewards in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder.,(1), 1−11.

Gray, S., Chaban, P., Martinussen, R., Goldberg, R., Gotlieb, H., Kronitz, R., … Tannock, R. (2012). Effects of a computerized working memory training program on working memory, attention, and academics in adolescents with severe LD and comorbid ADHD: A randomized controlled trial.,(12), 1277−1284.

Graziano, P. A., & Garcia, A. (2016). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and children's emotion dysregulation: A meta-analysis.,(7), 106−123.

Greene, C. M., Kennedy, K., & Soto, D. (2015). Dynamic states in working memory modulate guidance of visual attention: Evidence from an n-back paradigm.,(5), 546−560.

Grimm, O., van Rooij, D., Hoogman, M., Klein, M., Buitelaar, J., Franke, B., … Plichta, M. M. (2021). Transdiagnostic neuroimaging of reward system phenotypes in ADHD and comorbid disorders.,(9), 165−181.

Groves, N. B., Wells, E. L., Soto, E. F., Marsh, C. L., Jaisle, E. M., Harvey, T. K., & Kofler, M. J. (2022). Executive functioning and emotion regulation in children with and without ADHD.,(6), 721−735.

Hart, H., Radua, J., Nakao, T., Mataix-Cols, D., & Rubia, K. (2013). Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects.,(2), 185−198.

Hinshaw, S. P. (2018). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Controversy, developmental mechanisms, and multiple levels of analysis.(14)291−316.

Hoogman, M. (2020). Structural connectivity in ADHD: Evidence from 2500 individuals from the ENIGMA- ADHD collaboration.,(9), 87−87.

Hoogman, M., Bralten, J., Hibar, D. P., Mennes, M., Zwiers, M. P., Schweren, L. S., … Franke, B. (2017). Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: A cross-sectional mega-analysis.,(4), 310−319.

Hoogman, M., Muetzel, R., Buitelaar, J., Thompson, P. M., Faraone, S., Shaw, P., … Collaboration, E. A. (2019). Brain imaging of ADHD across the lifespan: Results of the largest study worldwide from the enigma ADHD working group.,(10), 6−7.

Howard, J. D., Reynolds, R., Smith, D. E., Voss, J. L., Schoenbaum, G., & Kahnt, T. (2020). Targeted stimulation of human orbitofrontal networks disrupts outcome-guided behavior.,(3), 490−498.

Hsu, C. -F., Benikos, N., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2015). Spontaneous activity in the waiting brain: A marker of impulsive choice in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder?,(1), 114−122.

Hung, Y., Gaillard, S. L., Yarmak, P., & Arsalidou, M. (2018). Dissociations of cognitive inhibition, response inhibition, and emotional interference: Voxelwise ALE meta-analyses of fMRI studies.,(10), 4065− 4082.

Irwin, L. N., Soto, E. F., Chan, E. S. M., Miller, C. E., Carrington-Forde, S., Groves, N. B., & Kofler, M. J. (2021). Activities of daily living and working memory in pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).,(4), 468−490.

Jackson, J. N., & MacKillop, J. (2016). Attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder and monetary delay discounting: A meta-analysis of case-control studies.,(4), 316−325.

Jacobson, L. A., Ryan, M., Martin, R. B., Ewen, J., Mostofsky, S. H., Denckla, M. B., & Mahone, E. M. (2011). Working memory influences processing speed and reading fluency in ADHD.,(3), 209−224.

Janssen, T. W. P., Heslenfeld, D. J., van Mourik, R., Gelade, K., Maras, A., & Oosterlaan, J. (2018). Alterations in the ventral attention network during the stop-signal task in children with ADHD: An event-related potential source imaging study.,(7), 639−650.

Jiang, X. X., Liu, L., Ji, H. F., & Zhu, Y. C. (2018). Association of affected neurocircuitry with deficit of response inhibition and delayed gratification in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A narrative review.,(10), 506−516.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994).New York, NY: Hachette Book.

Kallweit, C., Paucke, M., Strauß, M., & Exner, C. (2021). Adult ADHD: Influence of physical activation, stimulation, and reward on cognitive performance and symptoms.,(6), 809−819.

Karalunas, S. L., Antovich, D., Goh, P. K., Martel, M. M., Tipsord, J., Nousen, E. K., & Nigg, J. T. (2021). Longitudinal network model of the co-development of temperament, executive functioning, and psychopathology symptoms in youth with and without ADHD.,(5), 1803−1820.

Karr, J. E., Areshenkoff, C. N., Rast, P., Hofer, S. M., Iverson, G. L., & Garcia-Barrera, M. A. (2018). The unity and diversity of executive functions: A systematic review and re-analysis of latent variable studies.,(11), 1147−1185.

Kirk, U., Pagnoni, G., Hétu, S., & Montague, R. (2019). Short-term mindfulness practice attenuates reward prediction errors signals in the brain.,(1), 6964.

Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Yen, C. F., Chen, C. S., Lin, W. C., Wang, P. W., & Liu, G. C. (2013). Brain activation deficit in increased-load working memory tasks among adults with ADHD using fMRI.,(7), 561−573.

Kofler, M. J., Harmon, S. L., Aduen, P. A., Day, T. N., Austin, K. E., Spiegel, J. A., … Sarver, D. E. (2018). Neurocognitive and behavioral predictors of social problems in ADHD: A bayesian framework.,(3), 344−355.

Kofler, M. J., Irwin, L. N., Soto, E. F., Groves, N. B., Harmon, S. L., & Sarver, D. E. (2019). Executive functioning heterogeneity in pediatric ADHD.,(2), 273−286.

Kofler, M. J., Sarver, D. E., Austin, K. E., Schaefer, H. S., Holland, E., Aduen, P. A., …Lonigan, C. (2018). Can working memory training work for ADHD? Development of central executive training and comparison with behavioral parent training.,(12), 964−979.

Kofler, M. J., Soto, E. F., Fosco, W. D., Irwin, L. N., Wells, E. L., & Sarver, D. E. (2020). Working memory and information processing in ADHD: Evidence for directionality of effects.,(2), 127− 143.

Kofler, M. J., Wells, E. L., Singh, L. J., Soto, E. F., Irwin, L. N., Groves, N. B., … Lonigan, C. J. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of central executive training (CET) versus inhibitory control training (ICT) for ADHD.,(8), 738−756.

Kolling, N., Wittmann, M. K., Behrens, T. E. J., Boorman, E. D., Mars, R. B., & Rushworth, M. F. S. (2016). Value, search, persistence and model updating in anterior cingulate cortex.,(10), 1280−1285.

Kollins, S. H., DeLoss, D. J., Canadas, E., Lutz, J., Findling, R. L., Keefe, R. S. E., … Faraone, S. V. (2020). A novel digital intervention for actively reducing severity of paediatric ADHD (STARS-ADHD): A randomised controlled trial.,(4), 168−178.

Kral, T. R., Schuyler, B. S., Mumford, J. A., Rosenkranz, M. A., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Impact of short-and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli.,(9), 301−313.

Kryza-Lacombe, M., Palumbo, D., Wakschlag, L. S., Dougherty, L. R., & Wiggins, J. L. (2022). Executive functioning moderates neural mechanisms of irritability during reward processing in youth.,(5), e111483.

Lamichhane, B., Westbrook, A., Cole, M. W., & Braver, T. S. (2020). Exploring brain-behavior relationships in the N-back task.,(2), e116683.

Landis, T. D., Garcia, A. M., Hart, K. C., & Graziano, P. A. (2021). Differentiating symptoms of ADHD in preschoolers: The role of emotion regulation and executive function.,(9), 1260−1271.

Leffa, D. T., Grevet, E. H., Bau, C. H. D., Schneider, M., Ferrazza, C. P., da Silva, R. F., … Rohde, L. A. (2022). Transcranial direct current stimulation vs sham for the treatment of inattention in adults with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder the TUNED randomized clinical trial.,(9), 847−856.

Lemire-Rodger, S., Lam, J., Viviano, J. D., Stevens, W. D., Spreng, R. N., & Turner, G. R. (2019). Inhibit, switch, and update: A within-subject fMRI investigation of executive control.,(9), e107134.

Li, F., Cui, Y., Li, Y., Guo, L., Ke, X., Liu, J., … Leckman, J. F. (2022). Prevalence of mental disorders in school children and adolescents in China: Diagnostic data from detailed clinical assessments of 17, 524 individuals.,(1), 34−46.

Liu, L., Chen, W., Vitoratou, S., Sun, L., Yu, X., Hagger- Johnson, G., … Wang, Y. (2019). Is emotional lability distinct from “angry/irritable mood,” “negative affect,” or other subdimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in children with ADHD?,(8), 859−868.

Luck, S. J., & Vogel, E. K. (2013). Visual working memory capacity: From psychophysics and neurobiology to individual differences.,(8), 391−400.

Lugo-Candelas, C., Flegenheimer, C., Harvey, E., & McDermott, J. M. (2017). Neural correlates of emotion reactivity and regulation in young children with ADHD symptoms.,(7), 1311−1324.

Lukito, S., Norman, L., Carlisi, C., Radua, J., Hart, H., Simonoff, E., & Rubia, K. (2020). Comparative meta- analyses of brain structural and functional abnormalities during cognitive control in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder.,(6), 894−919.

Luna, B. (2009). Developmental changes in cognitive control through adolescence.,(1), 233−278.

Luna-Rodriguez, A., Wendt, M., Koerner, J. K. A., Gawrilow, C., & Jacobsen, T. (2018). Selective impairment of attentional set shifting in adults with ADHD.,(1), 18−29.

Luo, X., Guo, J., Liu, L., Zhao, X., Li, D., Li, H., … Sun, L. (2019). The neural correlations of spatial attention and working memory deficits in adults with ADHD.,(2), e101728.

Ma, I., van Duijvenvoorde, A., & Scheres, A. (2016). The interaction between reinforcement and inhibitory control in ADHD: A review and research guidelines.,(3), 94−111.

Martinelli, M. K., Mostofsky, S. H., & Rosch, K. S. (2017). Investigating the impact of cognitive load and motivation on response control in relation to delay discounting in children with ADHD.,(7), 1339−1353.

Marx, I., Hacker, T., Yu, X., Cortese, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2021). ADHD and the choice of small immediate over larger delayed rewards: A comparative meta-analysis of performance on simple choice-delay and temporal discounting paradigms.,(2), 171−187.

McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Future directions in childhood adversity and youth psychopathology.,(3), 361−382.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children.,(4907), 933−938.

Mitchell, J. T., McIntyre, E. M., English, J. S., Dennis, M. F., Beckham, J. C., & Kollins, S. H. (2017). A pilot trial of mindfulness meditation training for ADHD in adulthood: Impact on core symptoms, executive functioning, and emotion dysregulation.,(13), 1105−1120.

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis.,(1), 49−100.

Moriguchi, Y. (2021). Relationship between cool and hot executive function in young children: A near-infrared spectroscopy study.,(2), e13165.

Morris, S. S., Musser, E. D., Tenenbaum, R. B., Ward, A. R., Martinez, J., Raiker, J. S., … Riopelle, C. (2020). Emotion regulation via the autonomic nervous system in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Replication and extension.,(3), 361−373.

Mueller, A., Hong, D. S., Shepard, S., & Moore, T. (2017). Linking ADHD to the neural circuitry of attention.,(6), 474−488.

Mullane, J. C., Corkum, P. V., Klein, R. M., & McLaughlin, E. (2009). Interference control in children with and without Adhd: A systematic review of flanker and simon task performance.,(4), 321−342.

Musser, E. D., Backs, R. W., Schmitt, C. F., Ablow, J. C., Measelle, J. R., & Nigg, J. T. (2011). Emotion regulation via the autonomic nervous system in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).,(6), 841−852.

Nejati, V., Alavi, M. M., & Nitsche, M. A. (2021). The impact of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder symptom severity on the effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on inhibitory control.,(7), 248−257.

Nejati, V., Salehinejad, M. A., & Nitsche, M. A. (2018). Interaction of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l-DLPFC) and right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) in hot and cold executive functions: Evidence from transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS).,(1), 109−123.

Nejati, V., Salehinejad, M. A., Nitsche, M. A., Najian, A., & Javadi, A. -H. (2020). Transcranial direct current stimulation improves executive dysfunctions in ADHD: Implications for inhibitory control, interference control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility.,(13), 1928−1943.

Nigg, J. T., Sibley, M. H., Thapar, A., & Karalunas, S. L. (2020). Development of ADHD: Etiology, heterogeneity, and early life course.,(1), 559−583.

Norman, L. J., Carlisi, C., Lukito, S., Hart, H., Mataix-Cols, D., Radua, J., & Rubia, K. (2016). Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Comparative Meta-analysis.(8), 815−825.

O'Toole, S., Monks, C. P., & Tsermentseli, S. (2018). Associations between and development of cool and hot executive functions across early childhood.,(1), 142−148.

Ouellet, J., McGirr, A., van den Eynde, F., Jollant, F., Lepage, M., & Berlim, M. T. (2015). Enhancing decision-making and cognitive impulse control with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) applied over the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC): A randomized and sham-controlled exploratory study.,(7), 27−34.

Panichello, M. F., & Buschman, T. J. (2021). Shared mechanisms underlie the control of working memory and attention.,(7855), 601−605.

Patros, C. H. G., Alderson, R. M., Kasper, L. J., Tarle, S. J., Lea, S. E., & Hudec, K. L. (2016). Choice-impulsivity in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A meta-analytic review.,(2), 162−174.

Pauli-Pott, U., Schloss, S., Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M., & Becker, K. (2019). Multiple causal pathways in attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Do emerging executive and motivational deviations precede symptom development?,(2), 179−197.

Petersen, S. E., & Posner, M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after.(5), 73−89.

Petrovic, P., & Castellanos, F. X. (2016). Top-down dysregulation-from ADHD to emotional instability.,(70), 1−25.

Pievsky, M. A., & McGrath, R. E. (2018). The neurocognitive profile of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review of meta-analyses.,(2), 143−157.

Plichta, M. M., & Scheres, A. (2014). Ventral−striatal responsiveness during reward anticipation in ADHD and its relation to trait impulsivity in the healthy population: A meta-analytic review of the fMRI literature.,(1), 125−134.

Quentin, R., King, J. R., Sallard, E., Fishman, N., Thompson, R., Buch, E. R., & Cohen, L. G. (2019). Differential brain mechanisms of selection and maintenance of information during working memory.,(19), 3728−3740.

Rademacher, L., Krach, S., Kohls, G., Irmak, A., Gründer, G., & Spreckelmeyer, K. N. (2010). Dissociation of neural networks for anticipation and consumption of monetary and social rewards.,(4), 3276−3285.

Ramos, A. A., Hamdan, A. C., & Machado, L. (2020). A meta-analysis on verbal working memory in children and adolescents with ADHD.,(5), 873−898.

Rapport, M. D., Kofler, M. J., Alderson, R. M., Timko Jr, T. M., & DuPaul, G. J. (2009). Variability of attention processes in ADHD: Observations from the classroom.,(6), 563−573.

Re, A. M., Lovero, F., Cornoldi, C., & Passolunghi, M. C. (2016). Difficulties of children with ADHD symptoms in solving mathematical problems when information must be updated.,(10), 186−193.

Retz, W., Ginsberg, Y., Turner, D., Barra, S., Retz-Junginger, P., Larsson, H., & Asherson, P. (2021). Attention- Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), antisociality and delinquent behavior over the lifespan.,(1), 236−248.

Ron-Grajales, A., Sanz-Martin, A., Castañeda-Torres, R. D., Esparza-López, M., Ramos-Loyo, J., & Inozemtseva, O. (2021). Effect of mindfulness training on inhibitory control in young offenders.,(7), 1822− 1838.

Rosch, K. S., & Mostofsky, S. H. (2016). Increased delay discounting on a novel real-time task among girls, but not boys, with ADHD.,(1), 12−23.

Rosen, P. J., Walerius, D. M., Fogleman, N. D., & Factor, P. I. (2015). The association of emotional lability and emotional and behavioral difficulties among children with and without ADHD.,(4), 281−294.

Roshani, F., Piri, R., Malek, A., Michel, T. M., & Vafaee, M. S. (2020). Comparison of cognitive flexibility, appropriate risk-taking and reaction time in individuals with and without adult ADHD.,(2), e112494.

Rubia, K., Halari, R., Cubillo, A., Mohammad, A. M., Scott, S., & Brammer, M. (2010). Disorder‐specific inferior prefrontal hypofunction in boys with pure attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared to boys with pure conduct disorder during cognitive flexibility.,(12), 1823−1833.

Ryan, N. P., Catroppa, C., Ward, S. C., Yeates, K. O., Crossley, L., Hollenkamp, M., … Anderson, V. A. (2022). Association of neurostructural biomarkers with secondary attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptom severity in children with traumatic brain injury: A prospective cohort study.(8), 1−10.

Samea, F., Soluki, S., Nejati, V., Zarei, M., Cortese, S., Eickhoff, S. B., … Eickhoff, C. R. (2019). Brain alterations in children/adolescents with ADHD revisited: A neuroimaging meta-analysis of 96 structural and functional studies.,(5), 1−8.

Sayal, K., Prasad, V., Daley, D., Ford, T., & Coghill, D. (2018). ADHD in children and young people: Prevalence, care pathways, and service provision.,(2), 175−186.

Scheres, A., Milham, M. P., Knutson, B., & Castellanos, F. X. (2007). Ventral striatal hyporesponsiveness during reward anticipation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(5), 720−724.

Shakehnia, F., Amiri, S., & Ghamarani, A. (2021). The comparison of cool and hot executive functions profiles in children with ADHD symptoms and normal children.,(1), e102483.

Shaw, P., Gilliam, M., Liverpool, M., Weddle, C., Malek, M., Sharp, W., … Giedd, J. (2011). Cortical development in typically developing children with symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity: Support for a dimensional view of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.,(2), 143−151.

Shaw, P., Malek, M., Watson, B., Greenstein, D., de Rossi, P., & Sharp, W. (2013). Trajectories of cerebral cortical development in childhood and adolescence and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(8), 599−606.

Shaw, P., Stringaris, A., Nigg, J., & Leibenluft, E. (2014). Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.,(3), 276−293.

Shen, C., Luo, Q., Jia, T. Y., Zhao, Q., Desrivieres, S., Quinlan, E. B., … Consortium, I. (2020). Neural correlates of the dual-pathway model for ADHD in adolescents.,(9), 844−854.

Sheth, S. A., Mian, M. K., Patel, S. R., Asaad, W. F., Williams, Z. M., Dougherty, D. D., … Eskandar, E. N. (2012). Human dorsal anterior cingulate cortex neurons mediate ongoing behavioural adaptation.,(7410), 218−221.

Shulman, E. P., Smith, A. R., Silva, K., Icenogle, G., Duell, N., Chein, J., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation.,(2), 103−117.

Sibley, M. H., Mitchell, J. T., & Becker, S. P. (2016). Method of adult diagnosis influences estimated persistence of childhood ADHD: A systematic review of longitudinal studies.,(12), 1157−1165.

Silverstein, M. J., Faraone, S. V., Leon, T. L., Biederman, J., Spencer, T. J., & Adler, L. A. (2020). The relationship between executive function deficits and DSM-5-defined ADHD symptoms.,(1), 41−51.

Singh, L. J., Gaye, F., Cole, A. M., Chan, E. S. M., & Kofler, M. J. (2022). Central executive training for ADHD: Effects on academic achievement, productivity, and success in the classroom.,(4), 330−345.

Sjöwall, D., & Thorell, L. B. (2019). A critical appraisal of the role of neuropsychological deficits in preschool ADHD.,(1), 60−80.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2002). Psychological heterogeneity in AD/HD — A dual pathway model of behaviour and cognition. Behavioural brain research, 130(1-2), 29−36.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2003). The dual pathway model of AD/HD: An elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics.,(7), 593−604.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Becker, S. P., Bolte, S., Castellanos, F. X., Franke, B., Newcorn, J. H., … Simonoff, E. (2022). Annual Research Review: Perspectives on progress in ADHD science from characterization to cause.(4), 506−532.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Bitsakou, P., & Thompson, M. (2010). Beyond the dual pathway model: Evidence for the dissociation of timing, inhibitory, and delay-related impairments in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(4), 345−355.

Soto, D., Rotshtein, P., & Kanai, R. (2013). Parietal structure and function explain human variation in working memory biases of visual attention.,(4), 289−296.

Spiegel, J. A., Goodrich, J. M., Morris, B. M., Osborne, C. M., & Lonigan, C. J. (2021). Relations between executive functions and academic outcomes in elementary school children: A meta-analysis.,(4), 329−351.

Sripada, C., Kessler, D., Fang, Y., Welsh, R. C., Kumar, K. P., & Angstadt, M. (2014). Disrupted network architecture of the resting brain in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(9), 4693−4705.

Stalnaker, T. A., Cooch, N. K., & Schoenbaum, G. (2015). What the orbitofrontal cortex does not do.,(5), 620−627.

Steinberg, L., Albert, D., Cauffman, E., Banich, M., Graham, S., & Woolard, J. (2008). Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model.,(6), 1764−1778.

Sydnor, V. J., Cieslak, M., Duprat, R., Deluisi, J., Flounders, M. W., Long, H., … Oathes, D. J. (2022). Cortical-subcortical structural connections support transcranial magnetic stimulation engagement of the amygdala.,(25), eabn5803.

Tang, Y. -Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation.,(4), 213−225.

Tegelbeckers, J., Kanowski, M., Krauel, K., Haynes, J. D., Breitling, C., Flechtner, H. H., & Kahnt, T. (2018). Orbitofrontal signaling of future reward is associated with hyperactivity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(30), 6779−6786.

Thapar, A., Cooper, M., & Rutter, M. (2017). Neurodevelopmental disorders.,(4), 339−346.

Thornton, S., Bray, S., Langevin, L. M., & Dewey, D. (2018). Functional brain correlates of motor response inhibition in children with developmental coordination disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(9), 134−142.

Tripp, G., & Wickens, J. (2012). Reinforcement, dopamine and rodent models in drug development for ADHD.,(3), 622−634.

Utsumi, D. A., Miranda, M. C., & Muszkat, M. (2016). Temporal discounting and emotional self-regulation in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.,(10), 730−737.

van der Oord, S., Bögels, S. M., & Peijnenburg, D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents.,(1), 139−147.

van Dessel, J., Morsink, S., van der Oord, S., Lemiere, J., Moerkerke, M., Grandelis, M., … Danckaerts, M. (2019). Waiting impulsivity: A distinctive feature of ADHD neuropsychology?,(1), 122−129.

van Dessel, J., Sonuga-Barke, E., Mies, G., Lemiere, J., van der Oord, S., Morsink, S., & Danckaerts, M. (2018). Delay aversion in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is mediated by amygdala and prefrontal cortex hyper- activation.,(8), 888−899.

van Dessel, J., Sonuga-Barke, E., Moerkerke, M., van der Oord, S., Lemiere, J., Morsink, S., & Danckaerts, M. (2020). The amygdala in adolescents with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Structural and functional correlates of delay aversion.,(9), 673−684.

van Hulst, B. M., De Zeeuw, P., Bos, D. J., Rijks, Y., Neggers, S. F., & Durston, S. (2017). Children with ADHD symptoms show decreased activity in ventral striatum during the anticipation of reward, irrespective of ADHD diagnosis.,(2), 206−214.

van Rooij, D., Hartman, C. A., Mennes, M., Oosterlaan, J., Franke, B., Rommelse, N., … Hoekstra, P. J. (2015). Altered neural connectivity during response inhibition in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected siblings.,(1), 325−335.

von Rhein, D., Beckmann, C. F., Franke, B., Oosterlaan, J., Heslenfeld, D. J., Hoekstra, P. J., … Mennes, M. (2017). Network-level assessment of reward-related activation in patients with ADHD and healthy individuals.,(5), 2359−2369.

Walerius, D. M., Reyes, R. A., Rosen, P. J., & Factor, P. I. (2018). Functional impairment variability in children with ADHD due to emotional impulsivity.,(8), 724−737.

Wallis, G., Stokes, M., Cousijn, H., Woolrich, M., & Nobre, A. C. (2015). Frontoparietal and cingulo-opercular networks play dissociable roles in control of working memory.,(10), 2019−2034.

Wendt, M., Luna-Rodriguez, A., & Jacobsen, T. (2018). Shifting the set of stimulus selection when switching between tasks.,(1), 134−145.

Westwood, S. J., Radua, J., & Rubia, K. (2021). Noninvasive brain stimulation in children and adults with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis.,(1), 14−33.

Wiest, G. M., Rosales, K. P., Looney, L., Wong, E. G. E. H., & Wiest, D. J. (2022). Utilizing cognitive training to improve working memory, attention, and impulsivity in school-aged children with ADHD and SLD.,(2), e141.

Wolraich, M. L., Hagan, J. F., Allan, C., Chan, E., Davison, D., Earls, M., … Frost, J. (2019). Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents.,(4), e20192528.

Yang, D. Y., Chi, M. H., Chu, C. L., Lin, C. Y., Hsu, S. E., Chen, K. C., … Yang, Y. K. (2019). Orbitofrontal dysfunction during the reward process in adults with ADHD: An fMRI study.,(5), 627−633.

Yang, X., Gao, M., Shi, J., Ye, H., & Chen, S. (2017). Modulating the activity of the DLPFC and OFC has distinct effects on risk and ambiguity decision-making: A tDCS study.,(1417), 1417.

Yasumura, A., Omori, M., Fukuda, A., Takahashi, J., Yasumura, Y., Nakagawa, E., … Inagaki, M. (2019). Age-related differences in frontal lobe function in children with ADHD.,(7), 577−586.

Yu, X., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2020). Childhood ADHD and delayed reinforcement: A direct comparison of performance on hypothetical and real-time delay tasks.,(5), 810−818.

Zelazo, P. D. (2015). Executive function: Reflection, iterative reprocessing, complexity, and the developing brain.,(10), 55−68.

Zelazo, P. D. (2020). Executive function and psychopathology: A neurodevelopmental perspective.(2), 431−454.

Zelazo, P. D., & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity.,(4), 354−360.

Zelazo, P. D., & Müller, U. (2012). Executive function in typical and atypical development. In U. Goswami (Ed.),(pp. 574−603). Wiley-Blackwell.

Zhu, Y., Yang, D., Ji, W., Huang, T., Xue, L., Jiang, X., … Wang, F. (2016). The relationship between neurocircuitry dysfunctions and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A review.,(1),e3821579.

Zhu, Y. C., Jiang, X. X., & Ji, W. D. (2018). The mechanism of cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical neurocircuitry in response inhibition and emotional responding in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with comorbid disruptive behavior disorder.,(3), 566−572.

The mechanism of “cool”/“hot” executive function deficit acting on the core symptoms of ADHD children

WANG Xueke, FENG Tingyong

(Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China)

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a persistent neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity, which is closely related to the executive function deficits resulting from the dysplastic of prefrontal cortex. Based on the neuro-cognitive-behavioral developmental path, it is proposed that executive function deficits may be the pathogenesis of the core symptoms of ADHD at the cognitive level, among which the “cool” one related with the dorsal prefrontal cortex might be the dominant factor affecting inattention, and the “hot” one linked to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex could play the main role in the manifestation of hyperactivity-impulsivity. On the one hand, deficits in “cool” executive function mainly result in failures in working memory representation, lack of inhibitory control, and difficulties in cognitive flexibility, and further lead to limitations in attention maintenance, selection, and switching. On the other hand, deficits in “hot” executive function bring problems like delay aversion, reward abnormality and motivation disorders, which make one fail to inhibit behavior and more likely to make impulsive decisions, thereby displaying more symptoms of hyperactivity- impulsivity. Future studies are expected to examine and improve theoretical models of “hot” and “cold” executive function deficits affecting the core symptoms of ADHD, and provide more empirical evidence at the cognitive neural level. Meanwhile, future studies need to examine the mechanism mentioned above in ecological backgrounds, and further develop intervention projects with personalization, precision and long-acting to alleviate the core symptoms of ADHD based on executive function.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, executive function deficit, core symptom, prefrontal cortex, mechanism

2023-03-06

* 国家重点研发计划项目(2022YFC2705201)、重庆市博士研究生科研创新项目(CYB22099)、国家自然科学基金面上项目(32271123, 31971026)、西南大学创新研究2035先导计划(SWUPilotPlan006)资助。

冯廷勇, E-mail: fengty0@swu.edu.cn

B845