千岛湖片段化生境中木本植物种子雨基本特征及其影响因子

2023-11-01包明慧方中平胡来庭南歌徐高福于明坚

包明慧 方中平 胡来庭 南歌 徐高福 于明坚

摘 要:為探究片段化生境中木本植物种子雨的基本特征,该研究根据2015—2020年(研究期间)在千岛湖样岛上的植物群落长期监测样地内每月收集的种子雨数据,采用Kruskal-Wallis检验对木本植物的种子雨密度进行年际差异分析,对不同传播方式物种的种子雨密度进行月份间差异性分析,并利用线性混合效应模型,探究岛屿空间特征(岛屿面积、距最近岛屿的距离、距大陆的距离)以及气候因子(0 ℃以上积温、降水量)对木本植物以及不同传播方式物种的种子雨密度的影响。结果表明:(1)2015—2020年6年间,在29个样岛用240个收集器共收集到877 178粒木本植物的成熟种子,属于26科40属52种。(2)动物传播是木本植物主要的种子传播方式,不同传播方式物种的种子雨时间动态存在较大差异。(3)木本植物的种子雨年密度与岛屿面积和年积温呈显著正相关,与年降水量呈显著负相关。(4)自主传播物种的种子雨月密度与距最近岛屿的距离呈显著正相关,而动物传播物种的种子雨月密度则与距大陆的距离呈显著正相关,风力传播物种的种子雨月密度与月积温呈极显著正相关。综上表明,生境片段化通过岛屿空间特征影响了木本植物种子雨的时间动态。

关键词: 种子雨, 传播方式, 生境片段化, 时间动态, 木本植物

中图分类号:Q948

文献标识码:A

文章编号:1000-3142(2023)09-1600-11

收稿日期:2022-05-02

基金项目:国家自然科学基金 (31930073, 31870401); 国家重点研发计划政府间国际科技创新合作专项 (2018YFE0112800); 浙江省自然科学基金重大项目(LD19C030001)。

第一作者: 包明慧(1997-),硕士研究生,从事植物生态学研究,(E-mail)yuannnbao@163.com。

*通信作者:于明坚,博士,教授,研究方向为植物生态学和生物多样性,(E-mail)fishmj@zju.edu.cn。

Basic characteristics and influencing factors of seed

rain of woody plant in fragmented habitats

in the Thousand Island Lake

BAO Minghui1, FANG Zhongping2, HU Laiting3, NAN Ge4, XU Gaofu2, YU Mingjian1*

( 1. College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China; 2. Xin’an Jiang Ecological Development Group Co.,

LTD of Chun’an, Chun’an 311700, Zhejiang, China; 3. Chun’an County Forestry Bureau, Chun’an 311700,

Zhejiang, China; 4. Weinan Junior High School, Weinan 714000, Shaanxi, China )

Abstract:Seed rain can affect species composition, forest community diversity, and plant population and community renewal. Studying the characteristics of seed rain is of great significance for in-depth research on regeneration strategies and restoration of plant population. In order to explore the basic characteristics of seed rain in fragmented habitats, this study used monthly seed rain data collected from 2015 to 2020, and used the Kruskal-Wallis test to analyze the annual difference of the seed rain density of woody plant, and to analyze the monthly difference of the seed rain density of species with different dispersal syndromes. Then we used linear mixed-effect models to test the relationships among island spatial attributes (i. e., island area, the distance to the mainland, and the distance to the nearest island), climatic factors (i. e., accumulated temperature above 0 degrees, precipitation) and seed rain density of woody plant and species with different dispersal syndromes. The results were as follows: (1) During the six years of 2015-2020, a total of 877 178 mature seeds of woody plant were collected from 240 seed traps in 29 study islands, belonging to 26 families, 40 genera and 52 species. (2) Zoochory was the major dispersal syndrome in the Thousand Island Lake,there were great differences in the temporal dynamics of seed rain in different dispersal syndromes. (3) The annual density of seed rain of woody plant was significantly positively correlated with island area and annual accumulated temperature, and significantly negatively correlated with annual precipitation. (4) The monthly density of seed rain of autochory was significantly positively correlated with the distance to the nearest island, while that of zoochory was significantly positively correlated with the distance to the mainland, and that of anemochory was significantly positively correlated with the monthly accumulated temperature. In conclusion, habitat fragmentation affect the temporal dynamics of the seed rain of woody plant through island spatial attributes.

Key words: seed rain, dispersal syndrome, habitat fragmentation, temporal dynamic, woody plant

种子雨是指种子植物的种子或果实从母树向地表散落的过程(杜彦君和马克平,2012a)。种子雨是森林种群和群落更新的关键因子之一(Perini et al., 2019)。种子雨的时间动态是种子雨的基本特征之一,主要表现为群落、种群和个体水平上的季节动态和年际变化(于顺利等,2007; Wang et al., 2017)。由于种子受环境中生物因子和非生物因子的影响,这些因子包括温度和降水等非生物因子以及物种自身生物学-生态学特征如种子传播方式等,因此种子雨可作为种群和群落动态的指标(Rahbek, 2005; Barrett, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013)。del Cacho等(2013)发现,温度升高、年降雨量增加提升了多花欧石楠(Erica multiflora)的种子雨产量。Muller-Landau等(2008)对BCI(Barro Colorado Island)50 hm2 森林动态监测样地中41个树种的研究发现,种子传播方式相同的不同物种,其种子越重传播距离越近。

种子传播方式可分为自主传播和借物传播。其中,借物传播又可分为水力传播、风力传播和动物传播三大类;自主传播是指种子通过本身的构造机能,经由重力、弹跳或旋钻等方式离开母体甚或入土。种子因动物的携带而传播到他处称为动物传播。靠风力传播的传播方式称为风力传播(郭华仁,2019)。种子雨的季节性动态由不同的种子传播策略驱动(Li et al., 2012)。风力传播的物种倾向于在干季果实成熟传播,动物传播的物种倾向于在雨季果实成熟传播,这一结论已在多项研究中得到验证,如厄多瓜尔的季节性干旱热带森林(Jara-Guerrero et al., 2020)、巴西卡廷加旱生热带林(Griz & Machado, 2001)。种子传播对维持种群和群落结构等功能至关重要,但在片段化生境中,它是被破坏最严重的过程之一(Burns, 2005; McConkey et al., 2012; Emer et al., 2018)。

生境片段化是指连续的生境被分割成多个相互隔离的小斑块(片段)(Wilcove et al., 1986),及其带来的生境面积减小、生境隔离度增加和边缘效应增强等过程(Fischer, 2006)。生境片段化通常会导致生物同质化,从而导致群落以喜光和耐旱物种为主(Lobo et al., 2011),并加剧物种之间的竞争,减少了物种多样性(Bregman et al., 2015)。此外,生境片段化还会导致种子传播者的多度和丰富度的改变,尤其是大型种子扩散者的减少(Hagen et al., 2012),破坏了动物对种子的有效传播,减少了动物传播植物的补员率(Cordeiro & Howe, 2003; Lehouck et al., 2009),并导致植物灭绝概率最高可达10倍(Caughlin et al., 2014)。

在森林群落演替中,种子雨的动态是植物种群更新的限制因子(Barnes, 2001)。探究种子雨基本特征及其影响因子,对深入了解植物种群更新和群落演替趋势具有重要意义。目前,片段化生境中种子雨的研究主要集中在种子雨基本特征、种子雨的物种属性(如丰富度、生活型、扩散方式、演替状态和种子重量等),以及是否与片段化生境下斑块的空间特征(斑块的面积、数量以及边缘梯度)有关等(Burns, 2005; Jesus et al., 2012; Knorr & Gottsberger, 2012; McConkey et al., 2012; Freitas et al., 2013; Emer et al., 2018; Arreola et al., 2020; Camargo et al., 2020)。但是,從种子雨密度出发,探究生境片段化对不同传播方式物种的种子雨密度影响的研究仍然较少(San-Jose et al., 2020)。位于我国亚热带区域的千岛湖,其水库大坝建设形成了1 000多个相互隔离的陆桥岛屿,是研究生境片段化对植物种群更新和群落演替影响的理想平台。本文以千岛湖片段化生境为研究区域,利用2015—2020年间的种子雨数据,使用非参数检验以及线性混合模型等统计方法,拟探讨:(1)千岛湖岛屿上木本植物种子雨基本概况;(2)种子雨的时间动态;(3)气候因子以及生境片段化对种子雨的时间动态的影响。

1 材料与方法

1.1 研究区域概况

研究地点位于浙江省杭州市淳安县境内新安江水库(118°34′—119°15′ E、29°22′—29°50′ N),亦称千岛湖,是1959年新安江水电站建设蓄水形成的大型水库,水域面积约540 km2。该地区为典型的亚热带季风气候,温暖湿润,四季分明,雨热同期。年平均气温17 ℃,年最高气温41.8 ℃,年最低气温-7.6 ℃,年平均降水量1 430 mm(钟雨辰,2020)。水库大坝建设后岛上的原有森林基本被砍伐,同步开始次生演替,至今已有60余年(Liu et al., 2020)。森林覆盖率大于88.5%,主要为次生马尾松(Pinus massoniana)林。马尾松为建群种,林下以檵木(Loropetalum chinense)、短尾越橘(Vaccinium carlesii)和杜鹃(Rhododendron simsii)等小乔木和灌木为主(Liu et al., 2020)。

1.2 种子雨收集器的布置

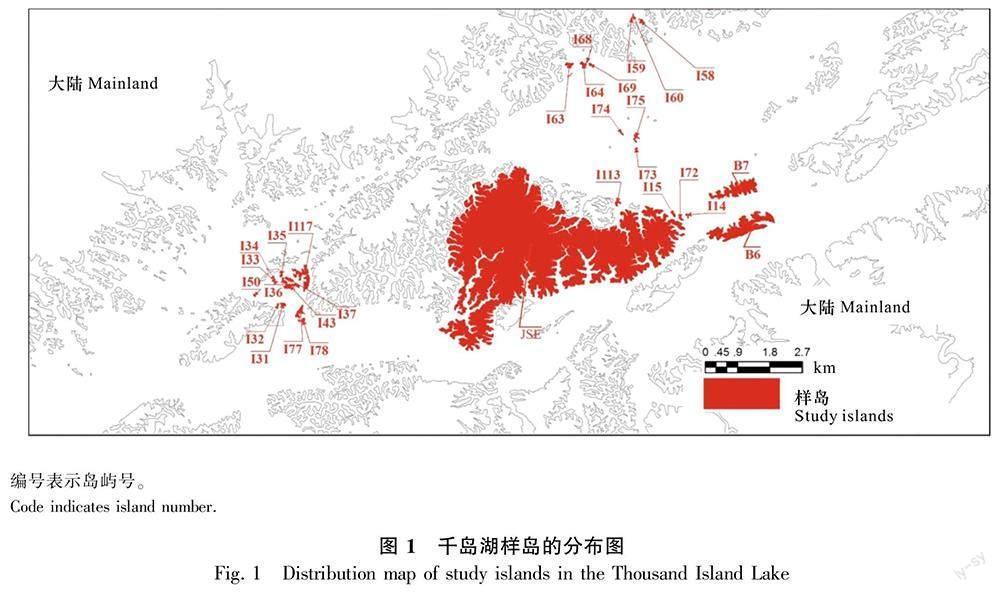

选取29个人为干扰较少且以马尾松林为主的岛屿作为植物群落样岛(图1)。2009—2010年,在样岛上建立了共12.7 hm2的植物群落长期监测样地,对样地内胸径 1 cm 以上的木本植物进行挂牌和调查,并于 2014—2015 年完成第一次复查工作。在29个岛屿的样地内,间距10~15 m的每个5 m × 5 m小样方中设置一个种子雨收集器。种子雨收集器由0.71 m × 0.71 m(0.5 m2)的PVC 框和 1 mm 网目的尼龙网组成,用4个高0.8 m的PVC管固定(南歌,2017)。29个样岛的样地内共设置240个种子雨收集器。2015年1月至2020年12月,每月对种子雨收集器内果实、种子进行一次收集,带回实验室用烘箱80 ℃烘48 h后,将收集物分成8类,分别为成熟果实、成熟种子、果皮果荚、碎片、未成熟的果实、花、动物咬过的果实、动物咬过的种子,对照花、果实、种子图谱进行物种识别,记数并称重(如果果实中含有1颗以上的种子,那么果实里的种子数要进行计数)(杜彦君和马克平,2012b)。成熟果实主要根据体积、形状、色泽等决定;若无法由外观决定,则可通过胚的形态和质地决定(杜彦君和马克平,2012a)。

1.3 数据分析和处理

本研究数据为2015年1月至2020年12月间收集的71次种子雨数据(2020年8—9月只收集1次数据)。根据果实类型、种子特征且结合野外实地观察及文献参考(杜彦君和马克平,2012b;Liu et al., 2019a),确定每个物种种子(果实)的传播方式。将物种分为动物传播、自主传播和风力传播三大类。种子雨密度用每平方米收集到的种子数量表达,即种子雨密度(seeds·m-2)=该物种在某岛屿上收集到的种子总粒数/对应岛屿的收集器总面积。气象数据为2015—2020年淳安县气象数据。由于种子雨密度不满足正态性和方差齐性,因此采用Kruskal-Wallis检验对木本植物的种子雨密度进行年际差异分析,对不同传播方式物种的种子雨密度进行月份间差异分析,并用线性混合效应模型,探究岛屿空间特征(岛屿面积、距最近岛屿的距离、距大陆的距离)和气候因子(0 ℃以上积温、降水量)对木本植物以及不同传播方式物种种子雨密度的影响。考虑到种子雨数据在不同月份和不同岛屿上的非独立性,在探究种子雨月密度变化的影响因子时将月份和岛屿编号作为随机截距项,而在探究种子雨年密度变化的影响因子时则将岛嶼编号作为随机截距项。以上非参数检验以及线性混合效应模型的分析,均对种子雨密度、岛屿面积进行了log对数转化。因为0 ℃以上积温与温度显著相关(Pearson相关性检验:r=0.99,P<0.001),故只选择了积温作为固定项进行分析。线性混合效应模型用lmer软件包完成,作图使用ggplot 2软件包完成,以上分析均在R 4.1.0软件(R Core Team, 2021)中完成。

2 结果与分析

2.1 种子雨概况

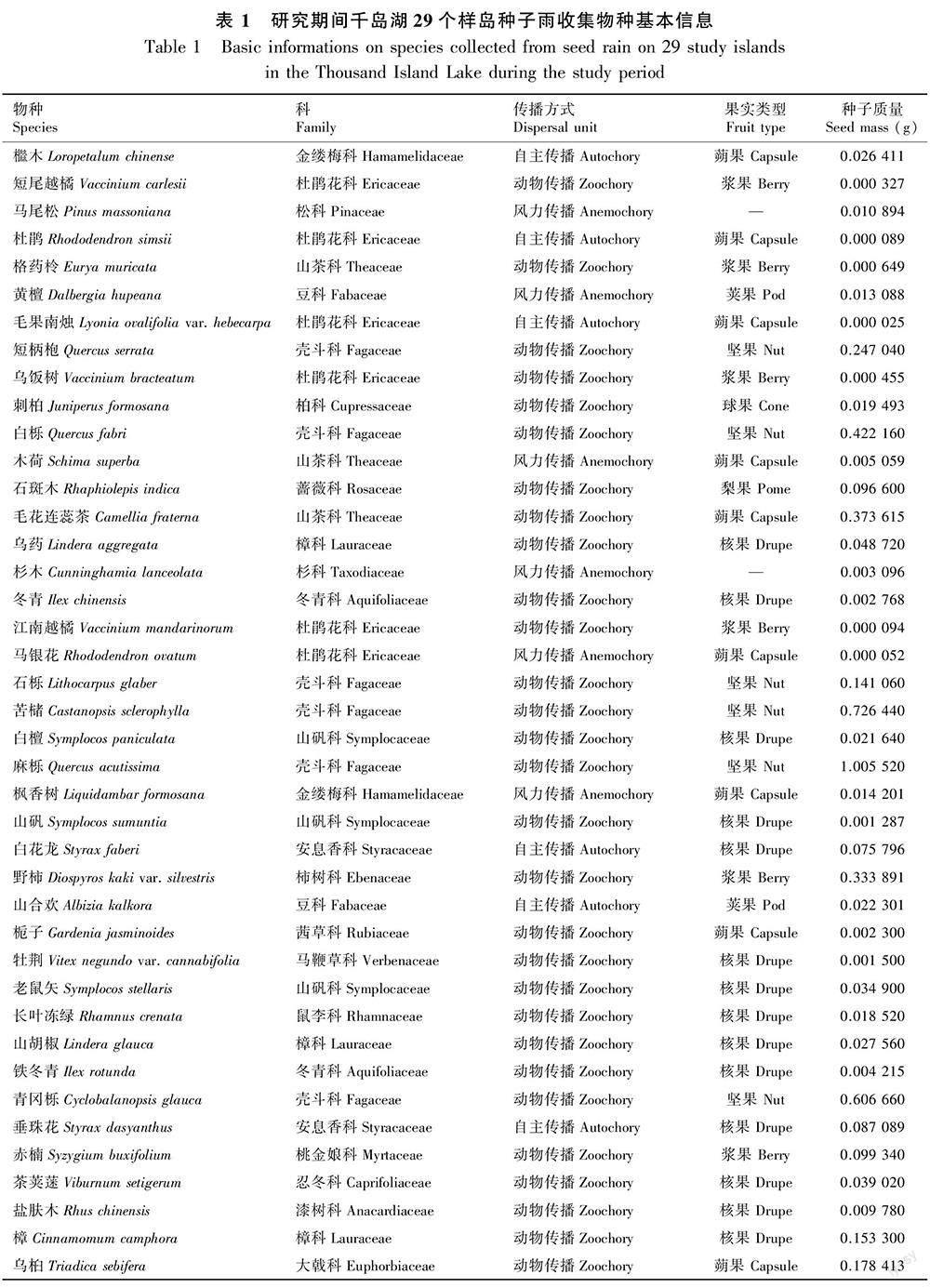

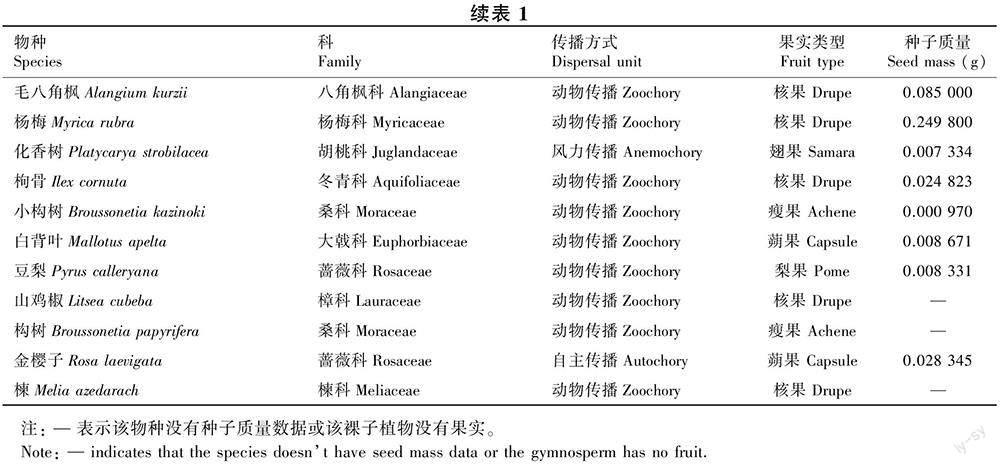

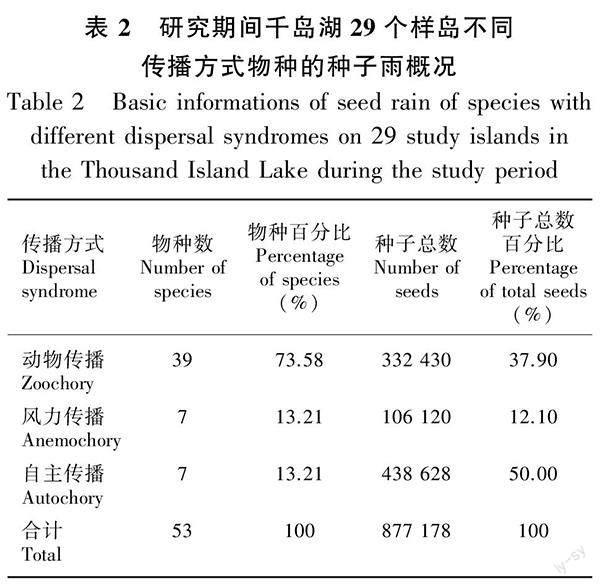

在2015—2020年的6年间,在29个岛屿用240个收集器共收集到877 178粒木本植物的成熟种子,属于26科40属52种 [其中,金樱子(Rosa laevigata)、楝(Melia azedarach)、构树(Broussonetia papyrifera)为样地调查没记录到的物种]。在2014—2015年样地复查中,在29个岛屿的样地内共记录到74种木本植物,其中共有25个物种没有收集到成熟种子。收集到种子数最多的10个物种分别为毛果南烛(Lyonia ovalifolia var. hebecarpa)、短尾越橘、格药柃(Eurya muricata)、马银花(Rhododendron ovatum)、马尾松、枫香树(Liquidambar formosana)、牡荆(Vitex negundo var. cannabifolia)、檵木、刺柏(Juniperus formosana)和木荷(Schima superba)。种子雨收集到的果实类型主要为核果和蒴果(表1)。从种子传播方式来看,动物传播的物种数量远高于风力传播与自主传播,分别占物种总数的73.58%、13.21%、13.21%(表2)。因此,动物传播是千岛湖马尾松林木本植物主要的种子传播方式。

2.2 种子雨时间动态

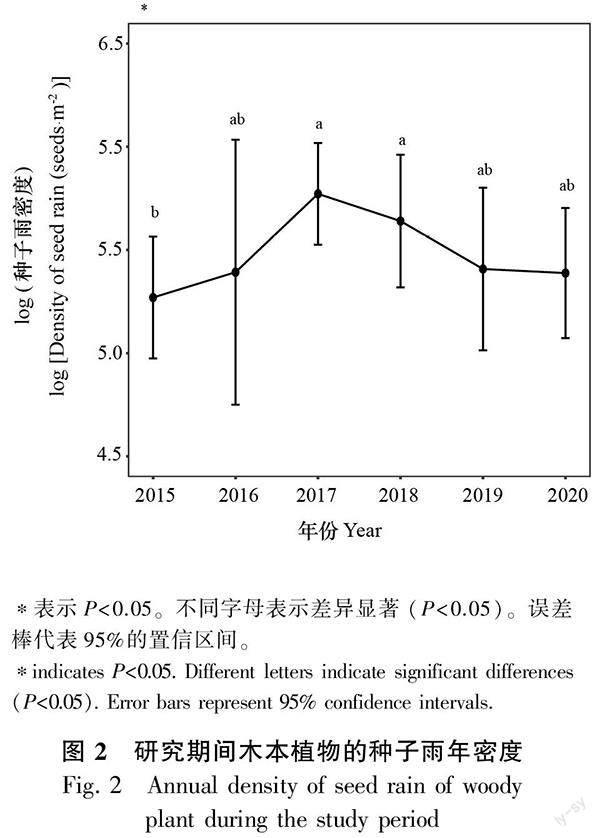

2.2.1 木本植物种子雨的年际变化 Kruskal-Wallis检验结果表明,2017年和2018年的种子雨密度均显著高于2015年的种子雨密度(P<0.05),其余年份之间差异不显著(图2)。

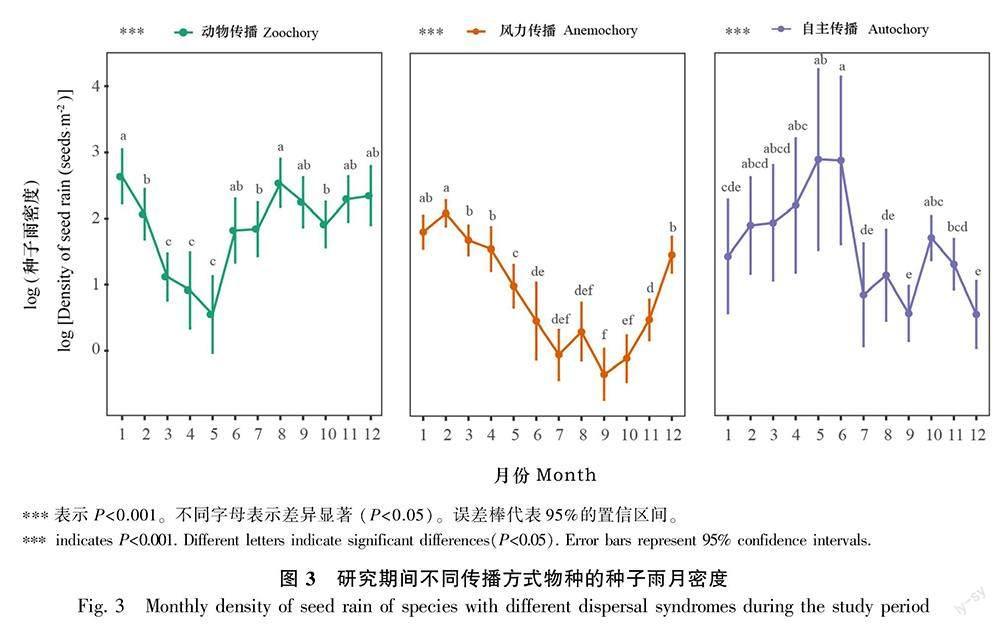

2.2.2 不同传播方式物种种子雨季节变化 不同传播方式物种的种子雨时间动态存在较大差异。动物传播物种的种子雨密度在8月至翌年1月期间达到高峰,在3—5月间到达低谷;风力传播的种子雨密度在1—2月间达到高峰,在6—8月间到达低谷;自主传播的种子雨密度在2—6月虽呈上升趋势,但相较于其他传播方式变异幅度较大,没有显著的高峰或低谷(图3)。

2.3 影响种子雨时间动态的因子

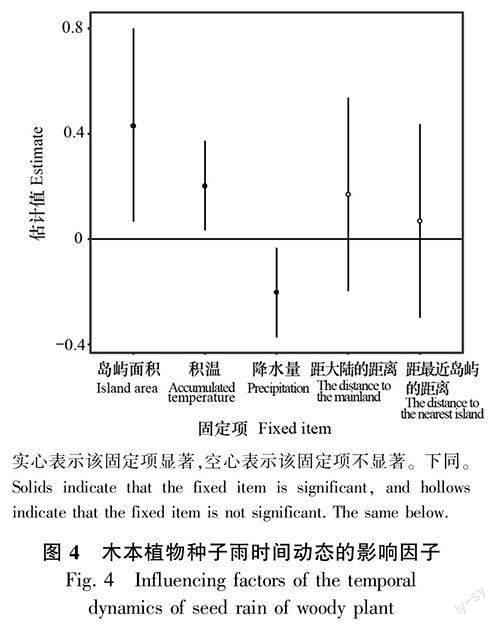

2.3.1 木本植物种子雨时间动态的影响因子 线性混合效应模型结果表明,木本植物的种子雨年密度与岛屿面积和年积温呈显著正相关(P<0.05),而与年降水量呈显著负相关(P<0.05)(图4)。

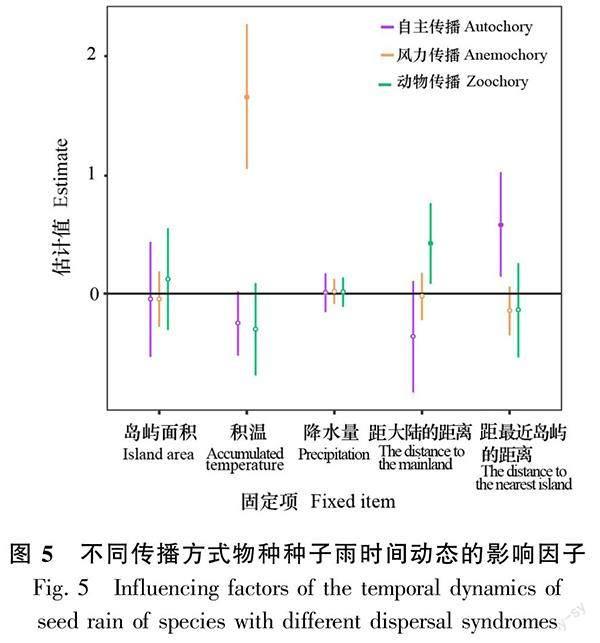

2.3.2 不同传播方式物种种子雨时间动态的影响因子 线性混合效应模型结果显示,不同传播方式物种的种子雨月密度对月积温、月降水量、岛屿面积、距最近岛屿的距离以及距大陆的距离均有不同程度的响应。自主传播物种的种子雨密度与距最近岛屿的距离呈显著正相关(P<0.05),风力传播物种的种子雨密度与月积温呈极显著正相关(P<0.001),动物传播物种的种子雨密度与距大陆的距离呈显著正相关(P<0.05)(图5)。

3 讨论

本研究在2015—2020年的6年间,通过种子雨共收集到52个木本物种的种子, 占千岛湖样地木本植物物种总数的67%。有33%的物种未收集到种子,其主要原因是存在种子限制(肖静等,2019),即扩散限制和源限制(Luo et al., 2013)。扩散限制是指种子不可能到达每个能支持萌发的地方;源限制是指因母树的种子产量低而影响幼苗的增补(Schupp et al., 2002)。这些未收到种子的物种,在样地中存在多度较低(仅占物种总多度的0.2%)、缺少母树、种子产量低的情况。同时,这些物种超过半数为灌木,树高较低(平均树高在1.7~3.3 m之间),种子的扩散距离有限,难以被收集。几年后,这些未收集到种子的物种更新会十分困难。

3.1 不同传播方式物种种子雨的季节动态

动物传播是千岛湖马尾松林木本植物主要的种子传播方式,这与其他亚热带森林种子雨研究结果一致(Du et al., 2009),也与热带森林种子雨研究结果一致(Frankie et al.,1974; Lieberman, 1982)。在千岛湖的马尾松林中,动物传播者主要是鸟类和啮齿类动物,并且鸟类传播物种数要大于哺乳动物传播物种数(Liu et al., 2019a)。这是因为鸟类通常是片段化森林中最重要的种子传播者,在森林恢复的早期参与种子传播(Pejchar et al., 2008; Garcia et al., 2010; Carlo & Morales, 2016; Martinez & Garcia, 2017)。例如,墨西哥的一项研究表明,在实验性次生林中增补物种大多数是鸟类或蝙蝠扩散的物种(de la Pena-Domene et al., 2014)。

植物往往倾向于在对其传播有利的时候进入繁殖期,以此最大幅度地提高种子扩散率和幼苗萌发率。本研究结果显示,风力传播与动物传播的物种均在秋冬季节达到种子雨密度的高峰。这种在秋冬季节出现结实高峰的现象,可以通过幼苗的建立来解释。例如,秋冬季风力更强,可使种翅充分展开,有利于翅果的传播(Sharpe & Fields, 1982)。如果亚热带森林中大部分种子在雨水较为充沛的夏季传播,那么种子将会很快发芽,幼苗也将经历漫长的冬季,这不利于幼苗的建立。在秋冬扩散的种子,因受水分与温度的限制而无法立刻萌发。到了翌年的3—4月,种子获得足够的水分和适宜的温度而萌发,接着经历几个月的生长,幼苗变得足够强壮,能抵挡翌年冬天的干旱和低温(杜彦君和马克平,2012b),这与华南地区香港灌丛繁殖物候的研究结果相似(Corlett & Richard, 1993)。同时,种子经过冬天的低温层积,可打破种子的休眠,从而增加种子的萌发率。

3.2 影响种子雨时间变化的因子

本研究表明,木本植物种子雨的年密度与岛屿面积呈显著正相关。Liu等(2019b)對千岛湖植物分布的研究表明,耐阴种的生物量与岛屿面积呈显著正相关,而非耐阴种则没有这种变化趋势。本研究中,耐阴植物种子数占种子雨总产量的40%,而树木的生物量在一定范围内与种子产量呈正比(Greene & Johnson, 1994)。由于耐阴种的生物量随着岛屿面积增加而增加,提高了耐阴种的种子产量,因此木本植物的种子雨密度随着面积增加而增加。同时,受边缘效应的影响,面积较小的岛屿更容易受到周围环境或基质干扰的影响,如水土流失严重(邬建国,2000),进而导致面积较小的岛屿种子产量下降。

种子产量与开花期有关(del Cacho et al., 2013)。影响开花期3个主要气候因子是温度、光周期和降水量,温度和降水量会因气候变化而显著改变(Rathcke & Lacey, 1985),从而导致开花物候的变化,进而使种子产量受到影响(Penuelas et al., 2002; Llorens & Penuelas, 2005; Ogaya & Penuelas, 2004, 2007)。千岛湖木本植物的种子雨年密度与年降水量呈显著负相关。Niklas(1985)的研究表明,空气湿度增加可以降低花粉的传播能力,从而影响种子产量。因此,降水量的增加会影响植物传粉,进而对种子雨密度产生负效应。千岛湖木本植物的种子雨年密度与年积温之间呈显著正相关,可从温度对植物的性能产生影响这一角度来解释。一方面,温度升高可以缓解开花期较低的温度对植物的负面影响,以此来提高植物繁殖能力(del Cacho et al., 2013)。另一方面,实验性地升高温度会促进植物的营养生长(Penuelas et al., 2004; Penuelas et al., 2007)。因此,在开花期提高温度会促进植物的营养生长和繁殖能力,从而提高种子的产量(del Cacho et al., 2013)。

本研究表明,动物传播物种的种子雨月密度与距大陆的距离呈显著正相关,即岛屿离大陆距离越近,岛屿上动物传播物种的种子雨密度越低,这可根据岛屿生物地理学中的“距离效应”来解释,即岛屿距离大陆越近,则物种的迁入率越高,反之越低(Macarthur & Wilson, 1963; MacArthur et al., 1967)。迁入率越高则意味着有更多的植物和动物迁入岛屿,越多的哺乳动物迁入岛屿,导致越多的动物传播物种的种子被哺乳动物取食或散播(García & Chinea, 2014),而我们设立的种子雨收集器收集到的大多是直接从树上掉落的果实和种子以及一部分鸟类取食果实后排出的种子。因此,哺乳动物取食或散播种子越多,种子雨收集器收集到的种子数量越低。

本研究发现,自主传播物种的种子雨月密度与距最近岛屿的距离成正比。Liu等(2020)的研究表明,在千岛湖片段化生境中,同种个体的空间作用强度,即它们之间的负相互作用随着距最近岛屿距离的增加而增加。这是因为在片段化生境中,植物及其天敌具有较高的扩散限制,因此导致宿主-天敌之间的相互作用或种内竞争更加激烈(Adler & Muller-Landau, 2005)。自主传播的扩散限制较强(雷霄,2014),在这种激烈的相互作用与种内竞争背景下,植物会通过增加种子产量、降低种子质量等方式来提高物种的存活率(Leslie et al., 2017)。因此,自主传播物种的种子雨月密度与距最近岛屿的距离成正比。

千岛湖风力传播物种的种子雨月密度与月积温呈极显著正相关,而积温对自主传播和动物传播产生负效应。种子产量的变化是因温度、降水等环境因子的改变而产生的一种进化策略(Walter & Johannes, 2000),不同生存策略的植物在种子数量变化上有不同体现:大种子植物往往会选择产出质量更大、数量更少的种子,而小种子植物则往往会选择产出质量更小、数量更多的种子(Leishman et al., 1995; Moles & Westoby, 2004)。风力传播物种种子平均质量最小,动物传播物种种子平均质量最大。因此,温度增加时,风力传播植物会选择产生更多更小的种子,而对动物传播植物来说,会产生更少更大的种子,自主传播植物的种子平均质量介于二者之间,可能选择的是产生更少更大的种子。本研究中,动物传播与自主传播的种子雨密度分别与距大陆的距离和距最近岛屿的距离呈显著正相关,从而导致积温对动物传播与自主传播的种子雨密度的负效应不显著。

4 结论

动物传播为千岛湖地区木本植物主要的种子传播方式;木本植物以及不同传播方式物种的种子雨密度对气候因子和岛屿空间特征的响应程度不同,生境片段化通过岛屿空间特征影响了种子雨的时间动态。本研究仅使用了6年的种子雨监测数据,后期可继续对千岛湖种子雨进行监测,同时将种子雨与后续生活史阶段进行比较研究,进一步探究片段化生境中植物群落的更新机制。

致謝 感谢浙江省淳安县新安江生态开发集团有限公司和淳安县林业局对本项目实施提供的支持;感谢巫东豪、阮振,千岛湖当地姜成仙、严建春、姜泉桂、周国娥以及童丽英等村民对种子雨收集和分类做出的贡献;感谢刘娟、韦博良、仲磊和刘金亮等对文章的撰写提出的宝贵意见。

参考文献:

ADLER FR, MULLER-LANDAU HC, 2005. When do localized natural enemies increase species richness?[J]. Ecol Lett, 8(4): 438-447.

ARREOLA FC, QUINTANA-ASCENCIO PF, RAMIREZ-MARCIAL N, et al., 2020. Seed rain and establishment in successional forests in Chiapas, Mexico[J]. Acta Bot Mex, 127(3): e1618.

BARRETT SCH, 2013. The evolution of plant reproductive systems: how often are transitions irreversible?[J]. Proc Roy Soc B-Biol Sci, 280(1765): 20130913.

BARNES ME, 2001. Seed predation, germination and seedling establishment of Acacia erioloba in northern Botswana[J]. J Arid Environ, 49(3): 541-554.

BREGMAN TP, LEES AC, SEDDON N, et al., 2015. Species interactions regulate the collapse of biodiversity and ecosystem function in tropical forest fragments[J]. Ecology, 96(10): 2692-2704.

BURNS KC, 2005. A multi-scale test for dispersal filters in an island plant community[J]. Ecography, 28(4): 552-560.

CAMARGO P, PIZO MA, BRANCALION PHS, et al., 2020. Fruit traits of pioneer trees structure seed dispersal across distances on tropical deforested landscapes: Implications for restoration[J]. J Appl Ecol, 57(12): 2329-2339.

CARLO TA, MORALES JM, 2016. Generalist birds promote tropical forest regeneration and increase plant diversity via rare-biased seed dispersal[J]. Ecology, 97(7): 1819-1831.

CAUGHLIN TT, FERGUSON JM, LICHSTEIN JW, et al., 2014. Loss of animal seed dispersal increases extinction risk in a tropical tree species due to pervasive negative density dependence across life stages[J]. Proc Roy Soc B-Biol Sci Ser B, 282(1798): 20142095.

CORDEIRO NJ, HOWE HF, 2003. Forest fragmentation severs mutualism between seed dispersers and an endemic African tree[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 100(24): 14052-14056.

CORLETT RT, 1993. Reproductive phenology of Hong Kong shrubland[J]. J Trop Ecol, 9(4): 501.

DE LA PENA-DOMENE M, MARTINEZ-GARZA C, PALMAS-PEREZ S, et al., 2014. Roles of birds and bats in early tropical-forest restoration[J]. PLoS ONE, 9(8): 1-6.

DEL CACHO M, ESTIARTE M, PENUELAS J, et al., 2013. Inter-annual variability of seed rain and seedling establishment of two woody Mediterranean species under field-induced drought and warming[J]. Popul Ecol, 55(2): 277-289.

DU YJ, MI XC, LIU XJ, et al., 2009. Seed dispersal phenology and dispersal syndromes in a subtropical broad-leaved forest of China[J]. For Ecol Manag, 258(7): 1147-1152.

DU YJ, MA KP, 2012a. Advancements and prospects in forest seed rain studies[J]. Biodivers Sci, 20(1): 94-107.[杜彥君, 马克平, 2012a. 森林种子雨研究进展与展望[J]. 生物多样性, 20(1): 94-107.]

DU YJ, MA KP, 2012b. Temporal and spatial variation of seed rain in a broad-leaved evergreen forest in Gutianshan Nature Reserve of Zhejiang Province, China[J]. Chin J Plant Ecol , 36(8): 717-728.[杜彦君, 马克平, 2012b. 浙江古田山自然保护区常绿阔叶林种子雨的时空变异[J]. 植物生态学报, 36(8): 717-728.]

EMER C, GALETTI M, PIZO MA, et al., 2018. Seed-dispersal interactions in fragmented landscapes — a metanetwork approach[J]. Ecol Lett, 21(4): 484-493.

FISCHER J, 2006. Habitat fragmentation and landscape Change: An Ecological and Conservation Synthesis[M]. Washington, DC: Island Press: 89-120.

FRANKIE GW, BAKER HG, OPLER PA, 1974. Comparative phenological studies of trees in tropical wet and dry forests in the lowlands of Costa Rica[J]. J Ecol, 62(3): 881-919.

FREITAS CG, DAMBROS C, CAMARGO JLC, 2013. Changes in seed rain across Atlantic Forest fragments in Northeast Brazil [J]. Acta Oecol, 53(11): 49-55.

GARCA AA, CHINEA D, 2014. Seed rain under native and non-native tree species in the Cabo Rojo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico[J]. Rev Biol Trop, 62(3): 1129-1136.

GARCIA D, ZAMORA R, AMICO GC, 2010. Birds as suppliers of seed dispersal in temperate ecosystems: conservation guidelines from real-world landscapes[J]. Conserv Biol, 24(4): 1070-1079.

GUO HR, 2019. Seed biology[M]. Beijing: Beijing United Publishing Co., Ltd:176-181.[郭华仁, 2019. 种子学[M]. 北京: 北京联合出版公司: 176-181.]

GREENE DF, JOHNSON EA, 1994. Estimating the mean annual seed production of trees[J]. Ecology, 75(3): 642-647.

GRIZL MS, MACHADO ICS, 2001. Fruiting phenology and seed dispersal syndromes in caatinga, a tropical dry forest in the northeast of Brazil[J]. J Trop Ecol, 17(2): 303-321.

HAGEN M, KISSLING WD, RASMUSSEN C, et al., 2012. Biodiversity, species interactions and ecological networks in a fragmented world[M]. San Diego: Advances in Ecological Research: 89-210.

JARA-GUERREROA, ESPINOSA CI, MENDEZ M, et al., 2020. Dispersal syndrome influences the match between seed rain and soil seed bank of woody species in a Neotropical dry forest[J]. J Veg Sci, 31(6): 995-1005.

JESUS FM, PIVELLO VR, MEIRELLES ST, et al., 2012. The importance of landscape structure for seed dispersal in rain forest fragments[J]. J Veg Sci, 23(6): 1126-1136.

KNORR UC, GOTTSBERGER G, 2012. Differences in seed rain composition in small and large fragments in the northeast Brazilian Atlantic Forest[J]. Plant Biol, 14(5): 811-819.

LEHOUCK V, SPANHOVE T, COLSON L, et al., 2009. Habitat disturbance reduces seed dispersal of a forest interior tree in a fragmented African cloud forest[J]. Oikos, 118(7): 1023-1034.

LEISHMAN MR, WESTOBY M, JURADO E, 1995. Correlates of seed size variation: a comparison among five temperate floras[J]. J Ecol, 83(3): 517-529.

LEI X,2014. The temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of seed rain by different dispersal modes in an evergreen broad-leaved forest in Tiantong, Zhejiang Province, Eastern China[D]. Shanghai: East China Normal University: 1-62.[雷霄, 2014. 浙江天童常綠阔叶林不同传播方式物种种子雨时空分布特征[D]. 上海: 华东师范大学: 1-62.]

LESLIE AB, BEAULIEU JM, MATHEWS S, 2017. Variation in seed size is structured by dispersal syndrome and cone morphology in conifers and other nonflowering seed plants[J]. New Phytol, 216(2): 429-437.

LI BH, HAO ZQ, BIN Y, et al., 2012. Seed rain dynamics reveals strong dispersal limitation, different reproductive strategies and responses to climate in a temperate forest in northeast China[J]. J Veg Sci, 23(2): 271-279.

LIEBERMAN D,1982. Seasonality and phenology in a dry tropical forest in Ghana[J]. J Ecol, 70(3): 791-806.

LIU JL, MATTHEWS TJ, ZHONG L, et al., 2020. Environmental filtering underpins the island species-area relationship in a subtropical anthropogenic archipelago[J]. J Ecol, 108(2): 424-432.

LIU JJ, SLIK F, COOMES DA, et al., 2019a. The distribution of plants and seed dispersers in response to habitat fragmentation in an artificial island archipelago[J]. J Biogeogr, 46(6): 1152-1162.

LIU JJ, COOMES DA, HU G, et al., 2019b. Larger fragments have more late-successional species of woody plants than smaller fragments after 50 years of secondary succession[J]. J Ecol, 107(2): 582-594.

LLORENS L, PENUELAS J, 2005. Experimental evidence of future drier and warmer conditions affecting flowering of two co-occurring Mediterranean shrubs[J]. Int J Plant Sci, 166(2): 235-245.

LOBO D, LEAO T, MELO FPL, et al., 2011. Forest fragmentation drives Atlantic forest of northeastern Brazil to biotic homogenization[J]. Divers Distrib, 17(2): 287-296.

LUO Y, HE F, YU SX, 2014. Recruitment limitation of dominant tree species with varying seed masses in a subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest[J]. Commun Ecol, 14(2): 189-195.

MACARTHUR RH, WILSON EO, 1963. Equilibrium-theory of insular zoogeography[J]. Evolution, 17(4): 373-387.

MACARTHUR RH, WILSON EO, MACARTHU RRH, et al., 1967. The theory of island biogeography[M]. New Jersey: Princeton University Press: 8-18.

MARTINEZ D, GARCIA D, 2017. Role of avian seed dispersers in tree recruitment in woodland pastures[J]. Ecosystems, 20(3): 616-629.

MCCONKEY KR, PRASAD S, CORLETT RT, et al., 2012. Seed dispersal in changing landscapes[J]. Biol Conserv, 146(1): 1-13.

MOLES AT, WESTOBY M, 2004. Seedling survival and seed size: a synthesis of the literature[J]. J Ecol, 92(3): 372-383.

MULLER-LANDAU HC, WRIGHT SJ, CALDERON O, et al., 2008. Interspecific variation in primary seed dispersal in a tropical forest[J]. J Ecol, 96(4): 653-667.

NAN G, 2017. Composition and dynamics of seed rain and soil seed bank in fragmented masson pine forests in the Thousand Island Lake region[D]. Jinhua: Zhejiang Normal University: 1-67.[南歌,2017. 千島湖库区马尾松林内种子雨和土壤种子库组成及动态[D]. 金华: 浙江师范大学: 1-67.]

NIKLAS KJ, 1985. The aerodynamics of wind pollination[J]. Bot Rev, 51(3): 328-386.

OGAYA R, PENUELAS J, 2004. Phenological patterns of Quercus ilex, Phillyrea latifolia, and Arbutus unedo growing under a field experimental drought[J]. Ecoscience, 11(3): 263-270.

OGAYA R, PENUELAS J, 2007. Species-specific drought effects on flower and fruit production in a Mediterranean holm oak forest[J]. Forestry, 80(3): 351-357.

PEJCHAR L, PRINGLE RM, RANGANATHAN J, et al., 2008. Birds as agents of seed dispersal in a human-dominated landscape in southern Costa Rica[J]. Biol Conserv, 141(2): 536-544.

PENUELAS J, FILELLA I, COMAS P, 2002. Changed plant and animal life cycles from 1952 to 2000 in the Mediterranean region[J]. Glob Change Biol, 8(6): 531-544.

PENUELAS J, FILELLA I, ZHANG XY, et al., 2004. Complex spatiotemporal phenological shifts as a response to rainfall changes[J]. New Phytol, 161(3): 837-846.

PENUELAS J, PRIETO P, BEIER C, et al., 2007. Response of plant species richness and primary productivity in shrublands along a north-south gradient in Europe to seven years of experimental warming and drought: reductions in primary productivity in the heat and drought year of 2003[J]. Glob Change Biol, 13(12): 2563-2581.

PERINI M, DIAS HM, KUNZ SH, 2019. The role of environmental heterogeneity in the seed rain pattern[J]. Floresta Ambiente, 26(1): 1-10.

RAHBEK C, 2005. The role of spatial scale and the perception of large-scale species-richness patterns[J]. Ecol Lett, 8(2): 224-239.

RATHCKE B, LACEY EP,1985. Phenological patterns of terrestrial plants[J]. Ann Rev Ecol Syst, 16(6): 179-214.

SAN-JOSE M, ARROYO-RODRIGUEZ V, MEAVE JA, 2020. Regional context and dispersal mode drive the impact of landscape structure on seed dispersal[J]. Ecol Appl, 30(2): 1-12.

SCHUPP EW, JORDANO P, GMEZ JM, 2010. Seed dispersal effectiveness revisited: a conceptual review[J]. New Phytol, 188(2): 333-353.

SHARPE DM, FIELDS DE, 1982. Integrating the effects of climate and seed fall velocities on seed dispersal by wind:A model and application[J]. Ecol Model, 17(3/4): 297-310.

WANG Y, ZHANG J, LAMONTAGNE JM, et al., 2017. Variation and synchrony of tree species mast seeding in an old-growth temperate forest[J]. J Veg Sci, 28(2): 413-423.

WALTER DK, JOHANNES MHK, 2000. Patterns of annual seed production by northern hemisphere trees: A global perspective[J]. Am Nat, 155(1): 59-69.

WU JG, 2000. Landscape ecology — concepts and theories[J]. Chin J Ecol, 19 (1): 42-52.[邬建国, 2000. 景观生态学——概念与理论[J]. 生态学杂志, 19(1): 42-52.]

WILCOVE DS, MCLELLAN CH, DOBSON AP, 1986. Habitat fragmentation in the temperate zone[M]. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates Inc: 237-256.

XIAO J, HUANG L, YANG C, et al., 2019. Composition and spatial-temporal variation of the seed rain in an evergreen broad-leaved forest on Jinyun Mountain[J]. Sci Silv Sin, 55(7): 163-169.[肖静, 黄力, 杨超, 等, 2019. 缙云山常绿阔叶林种子雨组成及其时空动态[J]. 林业科学, 55(7): 163-169.]

YU SL, LANG NJ, PENG MJ, et al., 2007. Research advances in seed rain[J]. Chin J Ecol, 26(10): 1646-1652.[于顺利, 郎南军, 彭明俊, 等, 2007. 种子雨研究进展[J]. 生态学杂志, 26(10): 1646-1652.]

ZHANG J, KISSLING WD, HE F, 2013. Local forest structure, climate and human disturbance determine regional distribution of boreal bird species richness in Alberta, Canada[J]. J Biogeogr, 40(6): 1131-1142.

ZHONG YC, 2020. Patterns and influencing factors of seed predation, dispersal and germination, and early-stage seedling establishment in a fragmented landscape, eastern China[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University: 1-73.[鐘雨辰, 2020. 片段化生境中种子捕食、扩散、萌发和幼苗早期建成模式及其影响因素[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学: 1-73.]

(责任编辑 蒋巧媛 王登惠)