The effect of urbanization and exposure to multiple environmental factors on life-history traits and breeding success of Barn Swallows(Hirundo rustica)across China

2022-10-03YnynZoEmilioPniYuLiuXioyinXinZiqinZnGunjiPnLutinSonXinLiZuoyZouYnqiuCnDonliLiYnLiuRbccSrn

Ynyn Zo ,Emilio Pni-Núñz ,Yu Liu ,Xioyin Xin ,Ziqin Zn ,Gunji Pn ,Lutin Son,Xin Li,Zuoy Zou,Ynqiu Cn,Donli Li,Yn Liu,Rbcc J.Srn

a State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol,School of Ecology,Sun Yat-sen University,Guangzhou,510006,China

b Institute of Eco-Environmental Research,Guangxi Academy of Sciences,Nanning,530007,China

c Department of Health and Environmental Sciences,Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University,Suzhou,215028,China

d Key Laboratory for Biodiversity Science and Ecological Engineering,Ministry of Education,College of Life Sciences,Beijing Normal University,Beijing,100091,China

e College of Wildlife and Protected Area,Northeast Forestry University,Harbin,150006,China

f Institute of Wildlife Conservation,Central South University of Forestry and Technology,Changsha,410004,China

g College of Life Science,Liaoning University,Shenyang,110036,China

h Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology,University of Colorado,Boulder,USA

Keywords:Fitness Heat-island effect Latitude Light pollution Noise pollution Parental investment

ABSTRACT In addition to landscape changes,urbanization also brings about changes in environmental factors that can affect wildlife.Despite the common referral in the published literature to multiple environmental factors such as light and noise pollution,there is a gap in knowledge about their combined impact.We developed a multidimensional environmental framework to assess the effect of urbanization and multiple environmental factors (light,noise,and temperature) on life-history traits and breeding success of Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) across rural to urban gradients in four locations spanning over 2500 km from North to South China.Over a single breeding season,we measured these environmental factors nearby nests and quantified landscape urbanization over a 1 km2 radius.We then analysed the relationships between these multiple environmental factors through a principal component analysis and conducted spatially explicit linear-mixed effects models to assess their effect on lifehistory traits and breeding success.We were particularly interested in understanding whether and how Barn Swallows were able to adapt to such environmental conditions associated with urbanization.The results show that there is significant variation in the exposure to environmental conditions experienced by Barn Swallows breeding across urbanization gradients in China.These changes and their effects are complex due to the behavioural responses ameliorating potential negative effects by selecting nesting sites that minimize exposure to environmental factors.However,significant relationships between landscape urbanization,exposure to environmental factors,and life-history traits such as laying date and clutch size were pervasive.Still,the impact on breeding success was,at least in our sample,negligible,suggesting that Barn Swallows are extremely adaptable to a wide range of environmental features.

1.Introduction

Three environmental factors-artificial light at night,environmental noise,and the heat-island effect-are commonly invoked in the literature as drivers of reduced fitness of vertebrates inhabiting urban environments.Artificial light at night disrupts key traits such as orientation during migration,energy expenditure and sleep(Dominoni et al.,2013;Da Silva et al.,2014;Ouyang et al.,2017;Welbers et al.,2017),driving potentially harmful behavioural and physiological changes(Gaston,2018).Noise pollution impairs communication and negatively affects the immune and hormonal systems(Barber et al.,2010;Kight and Swaddle,2011;Shannon et al.,2016).These two environmental factors have been linked to reduced nest success,yet the effects of the latter seem particularly pervasive (Senzaki et al.,2020).Finally,the heat-island effect-the rise of average temperatures of urban areas-drives body size shifts (Brans et al.,2017;Merckx et al.,2018) and has been linked to changes in species' breeding phenology (Møller et al.,2015).High temperatures typical of extreme environments can constrain breeding success (Stoleson and Beissinger,1999),which may be reinforced in urban areas within hot climates.However,there is a paucity of knowledge on the impact that increased exposure to these multiple environmental factors can have on vertebrates’breeding success across urban gradients.

Exposure to multiple environmental factors can result in particularly challenging conditions for organisms,an issue that has been particularly well studied in marine and wetland ecosystems (Crain et al.,2008;Ramírez et al.,2018;Sievers et al.,2018).In terrestrial ecosystems,birds are often used as a model taxon to investigate the consequences of urbanization.Environmental factors,such as temperature,noise or light,covary across urban gradients and can potentially be linked to variation in life-history traits and fitness(Sprau et al.,2017).Among these factors,environmental noise has been often linked to reduced fitness (Halfwerk et al.,2011;Kight et al.,2012;Schroeder et al.,2012;Injaian et al.,2018).Other studies examining the combined impact of multiple environmental factors in urban environments investigated response variables others than fitness including oxidative stress (Casasole et al.,2017),species composition (Ciach and Fröhlich,2017),and singing behaviour(Da Silva et al.,2014).A single study assessing the combined impact of artificial light,noise,humidity and temperature on Great Tits (Parus major)found that differences in fitness were attributable to urbanizationper serather than these environmental factors (Sprau et al.,2017).Moreover,previous research using birds as models have focused on cavity nesters,such as the Tree Swallow(Tachycineta bicolor),the Great Tit or the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus),breeding in temperate regions within Europe and the United States of America(e.g.,Senzaki et al.,2020).Thus,there is a need for studies 1) examining the impact of multiple environmental factors on reproductive fitness,2)particularly in species building open nests,which likely are more exposed to the detrimental effects of urbanization than cavity nesters whose nesting environment is insulated from direct exposure to light and noise,and 3)across latitudinal gradients encompassing different climates.

Using a multidimensional environmental framework,we investigated the impact that multiple environmental factors combined (diurnal and nocturnal light intensity,environmental noise,and air temperature)have on different life-history traits (laying date,clutch size and breeding success measured as the ratio between number of fledglings and clutch size during a single breeding attempt)of Barn Swallows(Hirundo rustica)breeding across urban gradients over a single breeding season (2018).This relatively small migratory passerine is a highly suitable model species to investigate the consequences of urbanization and exposure to environmental factors.It is found in both urban and rural areas thereby enabling a natural comparative experiment.Moreover,it is well-adapted to thrive in human-dominated environments(Zink et al.,2006;Dor et al.,2010).We conducted this study in China,a country that is experiencing one of the fastest urbanization rates in the world(Seto et al.,2011),over a large geographical area encompassing 22°of latitude and 9°of longitude.Most previous studies have investigated the impact of single environmental factors on fitness at the city level.For instance,environmental noise drives a reduction in clutch size of domestic Atlantic Canaries(Serinus canaria)(Huet des Aunay et al.,2017),and in breeding success of Tree Swallows (Injaian et al.,2018).Birds breeding in urban areas sometimes lay earlier and smaller clutches than those in rural areas,as e.g.,Great Tits (Caizergues et al.,2018),yet the relative importance of landscape changes and the myriad associated environmental factors have in shaping such patterns remains unclear.

In this study,we provide a comprehensive study of the consequences for life-history traits and fitness by examining the interactions between landscape changes and exposure to environmental factors across a wide geographical area.We aimed to determine whether breeding Barn Swallows were able to adapt to such different environmental conditions.Also,we were interested in determining what behavioural responses were elicited by multiple environmental factors and urbanization at their nests.After controlling for the effect of longitude and latitude using a linear correlation structure in our models,we were interested in discerning the effects that landscape urbanization and multiple environmental factors have on laying date,clutch size,and breeding success of Barn Swallows.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Study area and field methods

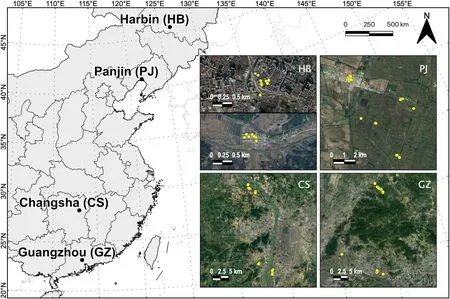

We performed this study over a single breeding season in 2018 in four locations across a large geographical area of 22°of latitude and 9°of longitude(Fig.1).These locations,from south to north,were Guangzhou(Guangdong,South China),Changsha (Hunan,South-Central China),Panjin(Liaoning,Northeast China)and Harbin(Heilongjiang,Northeast China)(Appendix Table S1).We worked in urban and rural areas at each location (Fig.2).We quantified built land cover around the nests using ArcGIS 10.1 with data extracted from http://www.earthenv.org following a standard protocol (Tuanmu and Jetz,2014).Built areas refer to the proportion of land surface within a 1-km pixel grid covered by any artificial constructions,which can be used to measure the urbanization level(Guo et al.,2016).

We searched for Barn Swallow nests under construction in suitable areas across our sampling locations as soon as Barn Swallows appeared in the early spring,to make sure we obtained data from first breeding attempts.Due to the wide latitudinal gradient considered in this study,the onset and duration of the breeding season varied considerably among our study locations.From south to north,laying dates ranged between March 17th and May 30th in Guangzhou,between April 20th and May 25th in Changsha,between May 13th and June 17th in Panjin,and between May 17th and June 13th in Harbin.Once an active nest was found,we assigned it a unique nest identification code and checked it regularly every three to four days to determine laying date(i.e.,date in which the first egg was laid),clutch size (number of eggs) and breeding success(ratio of nestlings that fledged vs clutch size).Sample size was slightly smaller for breeding success because we could not access some nests after determining clutch size(e.g.,because property owners were absent)(n=120 vs.n=103).We assumed that nestlings had successfully fledged if they were still present in the last visit (12-15 days),less than a week before all the nestlings left the nest (Grüebler et al.,2010).Since breeding Barn Swallows may respond negatively to human disturbance associated with direct nest checking,we recorded our data on environmental factors during the late incubation period to minimize the chances of nest desertion and to avoid interfering with nestling rearing.We assumed that exposure to environmental factors would be relatively constant across the entire breeding attempt and certainly less variable than differences between nests and locations.Finally,we only used data from first breeding attempts,as data from second breeding attempts were not systematically recorded,and to avoid pseudo-replication because we were unable to band,and thus uniquely identify,the parents in all locations.

2.2.Recording environmental factors

During the incubation stage,10-12 days after the laying date,we attached two data-loggers within a 50 cm radius below the nest to record light intensity (i.e.,illuminance) (lux),environmental noise (dBA) and air temperature(°C)at a total of 120 nests.Barn Swallows resumed their normal behaviour within 0.5 h after the installation of these devices.Data were recorded continuously every 2 min for 48 h to ensure continuous and complete diurnal cycles for both data-loggers.

Fig.1.Left:Study locations across 22° of latitude and 9° of longitude in the P.R.of China.Right:Satellite images of study locations in which nest sites are indicated with yellow points.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend,the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Air temperature and light intensity were recorded using a HOBO Pendant ® Temperature/Light 8K Data Logger-UA-002-08 (Onset,MA,USA).Measurement range is -20°to 70°C for temperature and 0 to 320,000 lux (i.e.,lumens per square foot) for light.Accuracy of temperature measurements was±0.53°C from 0°to 50°C.The light loggers measure light levels ranging from infrared to UV (175-1200 nm,including the 300-700 nm range visible to the bird eye (Håstad andÖdeen,2014)) and thus detect wavelength ranges visible to birds.The light sensor is designed to detect relative changes rather than absolute values,which was especially useful for our research objectives.Furthermore,this instrument is capable of measuring light at very low levels,which was particularly important to detect artificial light pollution at night.Light intensity in our sample ranges from 0 lux(no light)to several thousand lux(very bright light).Since environmental conditions were highly variable among habitats and locations,we used this information to determine dawn(light >0 lux)and dusk (light=0 lux)and,therefore,night duration.Thus,night duration,time during which a nest did not receive diurnal light,was a relative measure according to the particular environmental conditions at each nest,rather than actual dawn and dusk(Dominoni and Partecke,2015).We used night duration as an important environmental factor because it is commonly assumed that excessively short nights may lead to insufficient sleeping time,thus negatively affecting individual health(Cirelli and Tononi,2008).

Environmental noise was recorded using a CEM®Sound Level Data-Logger DT-173 (CEM,Shenzhen,China).Every 2 min,the data-logger measured 20 data points in dBA at 50 ms (millisecond) intervals and stored the average value in fast-response mode (125 ms).Accuracy was±1.4 dBA.Average environmental noise ranged between 35 and 65 dBA in our sample,often well above of the values described to have a negative impact on wildlife (Shannon et al.,2016).The maximum acceptable values for humans recommended by the World Health Organization(WHO)are 30-45 dB for sleeping,50-55 dB for outdoor living areas,and 70-85 dB to affect auditory capacity(World Health Organization,1999).

At each nest,we continuously computed night duration,diurnal and nocturnal light intensity,environmental noise,and air temperature during a 48-h sampling period,which we then averaged to characterize exposure to these multiple environmental factors.

2.3.Statistical analyses

To understand how these multiple environmental factors were related to each other,we ran a principal component analysis (PCA) using the seven dependent variables previously described (average diurnal and nocturnal light intensity [i.e.,daylight and artificial light pollution at night],average night duration,average diurnal and nocturnal environmental noise,and average diurnal and nocturnal temperature)from 120 nests of Barn Swallows.Our main objective was to assess the combined effects of these factors on fitness,and their correlation with latitude,urbanization,and life-history traits.Thus,we were particularly interested in obtaining components integrating variability of these multiple environmental factors.We performed a PCA of correlation matrix(i.e.a singular value decomposition of a column-centered and scaled matrix).Thus,our study variables were centered and scaled,subtracting mean variable values from each score and dividing these scores by the standard deviation.This procedure removed heterogeneity of variance associated with the different ranges of variation and measurement units among our environmental variables.

Additionally,we performed a Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling(NMDS) based on the Bray-Curtis distance of the same study variables.We applied a Wisconsin double standardization,in which variables(columns) are first standardized by its maximum value and then nests(lines) by the total line values.The first axis from the NMDS analysis showed similar scores to the first component of the PCA (r=0.8,P<0.01,Appendix Fig.S1).Moreover,the first ten axes from the NMDS analysis showed optimal stress scores (all <0.05) (Clarke,1993),suggesting that a single axis would be sufficient to satisfactorily explain data variability.This result,and the high similarity between the scores from both approaches,led us to retain the PCA approach,which is frequently used to reduce the dimensionality of multiple environmental variables(Badgley and Fox,2000;Pagani-Núñez et al.,2014).

Fig.2.Typical nest sites of Barn Swallows in our study locations.In southern China,Barn Swallows(Hirundo rustica)usually nest outside of the first floor of buildings,which are often low and sparse in rural areas(A),while tall and dense in urban areas(B).In some rural areas,they may also nest in the open main room on the ground floor(e.g.,Changsha).In northern China,Barn Swallow nests in rural areas are usually located in open yards,and these houses are usually low,with only one floor in both Harbin and Panjin (C).Sometimes,in urban areas,Barn Swallows may nest inside old buildings and enter and exit through the windows of stairwells (D).

Using the PCA approach,we extracted three relevant components with eigenvalues higher than 1.We determined the relative importance of the different study variables for a component according to their principal coordinates(i.e.,correlation coefficients between variables and components >0.70).We report correlations among our study variables in Appendix Table S2,and descriptive statistics for all our study variables by location in Appendix Table S3.

We first ascertained the relationships between the three PCA components and built land cover (built area within 1 km2of the nest)using a linear mixed-effect models fit by restricted maximum likelihood(REML).We ran three models sequentially using each of the three PCA components as dependent variable and landscape urbanization as independent variable.Since variability in artificial light pollution at night was not captured with any component,we ran an additional model including this environmental factor as dependent variable.These were spatially explicit models (Dormann et al.,2013);we included latitude and longitude as correlation structure and location as random factor (Changsha,Guangzhou,Harbin or Panjin).When two nests had the same coordinates we added a decimal point,which represented a negligible distance,as the difference between two points cannot be zero using this approach.We also assessed differences among study locations for these three components through an analysis of variance and Tukey multiple comparisons of means.

We then ran a model following the same procedure but using laying date(date on which the first egg was laid measured asNdayssince March 1st),as a dependent variable and landscape urbanization and the three PCA components and artificial light pollution at night as independent variables.We did the same alternatively using clutch size (Neggs) and breeding success (Nfledglings/Neggs) as dependent variables and adding laying date as independent variable.We applied model selection and averaging procedures to these models based on Akaike Information Criterion corrected by sample size(AICc),and retained results of conditional averages of the selected models (ΔAICc <2) (Symonds and Moussalli,2011).When performing model averaging,we fit the models by maximum likelihood,which is the appropriate approach for model comparisons(Zuur et al.,2009).When only one model was retained,we reran the model using a REML fit and provide these results.We also computed variation inflation factors of all models including several independent variables to assess multicollinearity.All variables gave scores lower than 3,which suggests absence of multicollinearity (Henseler et al.,2009).Finally,we retained the residuals accounting for fixed factors’effects from the models using clutch size and breeding success as dependent variables.Using these residuals,we assessed differences in these variables between study locations through an analysis of variance and Tukey multiple comparisons of means.All variables were scaled by subtracting the mean variable values from each score and diving these scores by the standard deviation,to reduce heteroscedasticity and approximate normal distributions.In the case of laying date,we performed this scaling procedure by subtracting the mean per location and dividing by overall standard deviation.In doing so,we obtained normalized values that enabled us performing meaningful comparisons between locations(labeled“normalized laying date”).

We carried out all the analyses in R software 4.0.5 (R Core Team,2021),and used the packages FactoMineR v1.41(Lê et al.,2008),vegan v2.5-7 (Oksanen et al.,2007),MuMIn v1.43.17 (Bartoń,2022),car v3.0-11 (Fox et al.,2012),and nlme v3.1-152 (Pinheiro et al.,2007) to run these analyses.

3.Results

3.1.Relationships among environmental factors

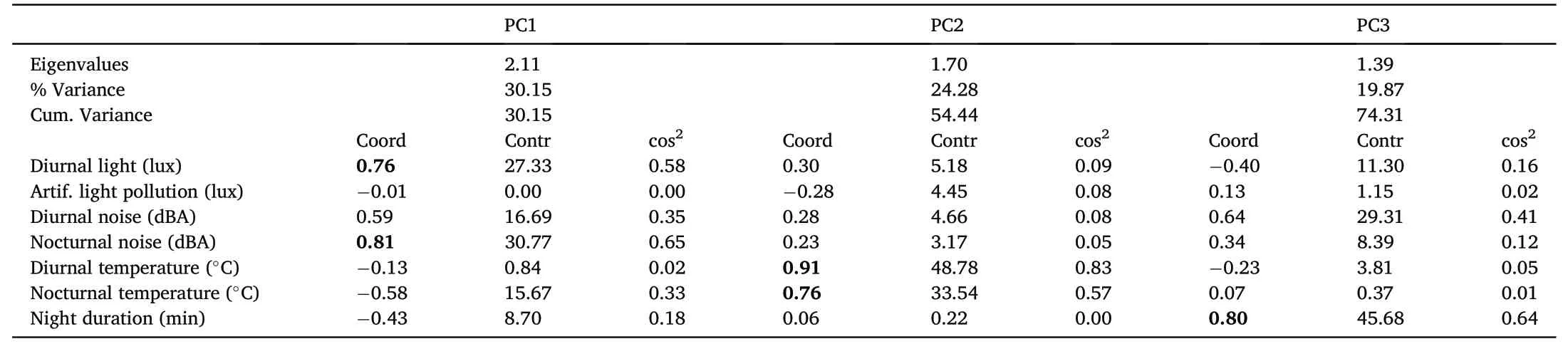

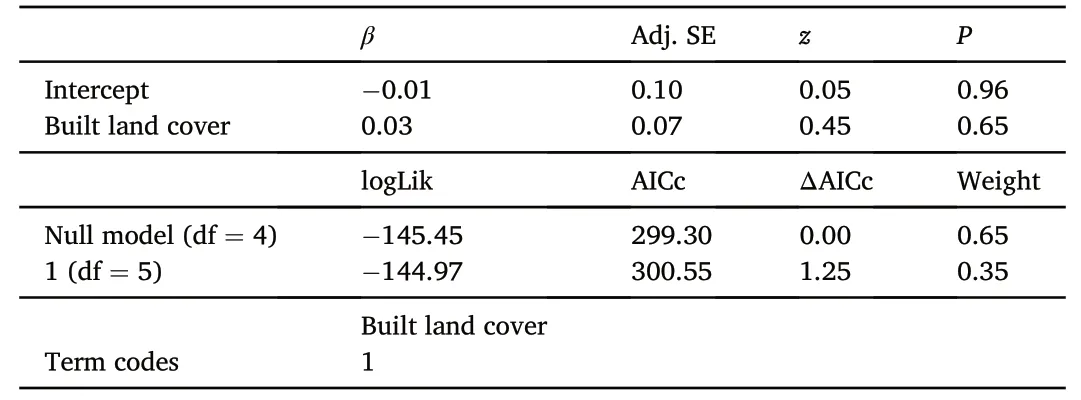

We obtained three components with eigenvalues higher than 1(Table 1).PC1 correlated positively with nocturnal noise(r=0.81)and diurnal light (r=0.76).PC1 explained 30.15% of variance.PC2 correlated positively with diurnal (r=0.91) and nocturnal temperature (r=0.76) and explained 24.28% of variance.PC3 correlated positively with night duration(r=0.80)and explained 19.87% of variance.These three components explained a total of 74.30% of variance.Based on these scores,we characterized these components as “nest exposure” (PC1),“nest temperature” (PC2),and“night duration” (PC3).

3.2.Relationships between environmental factors and landscape urbanization

Spatially explicit linear-mixed effects models accounting for variation in latitude and longitude showed that landscape urbanization did not correlate with PC1(β±SE=-0.15±0.10,t115=-1.51,P=0.13),PC2(β±SE=0.10±0.10,t115=1.02,P=0.31),or artificial light pollution at night(β±SE=-0.09±0.15,t115=-0.61,P=0.54),but correlated positively with PC3 (β ± SE=0.36 ± 0.07,t115=4.98,P<0.01)(Fig.3A).Locations showed significant differences in PC1(F3,116=4.83,P<0.01),yet only Panjin showed significantly higher PC1 scores than Changsha(P=0.02,95%CI=0.10-1.53)and Harbin(P=0.03,95%CI=0.05-1.40)(Fig.3B).Locations showed significant differences in PC2(F3,116=4.43,P=0.01),yet only Changsha displayed significantly higher values than Panjin(P=0.04,95%CI=0.04-1.48)and Harbin(P=0.04,95% CI=0.02-1.72) (Fig.3B and C).Locations also showed multiple significant differences in PC3 (F3,116=29.63,P<0.01),with Guangzhou showing significantly higher values than all the other cities(allP<0.04) and Changsha showing higher values than Panjin and Harbin (allP<0.02) (Fig.3C).Locations did not show significant differences in artificial light pollution at night (F3,116=0.92,P=0.43).

3.3.Factors shaping life-history traits and breeding success of Barn Swallows

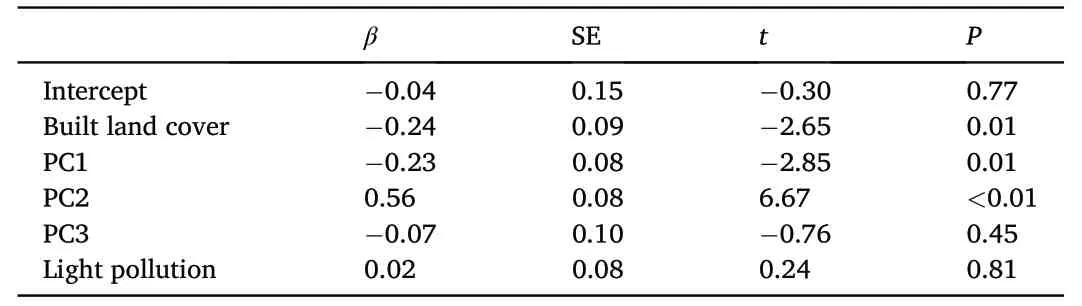

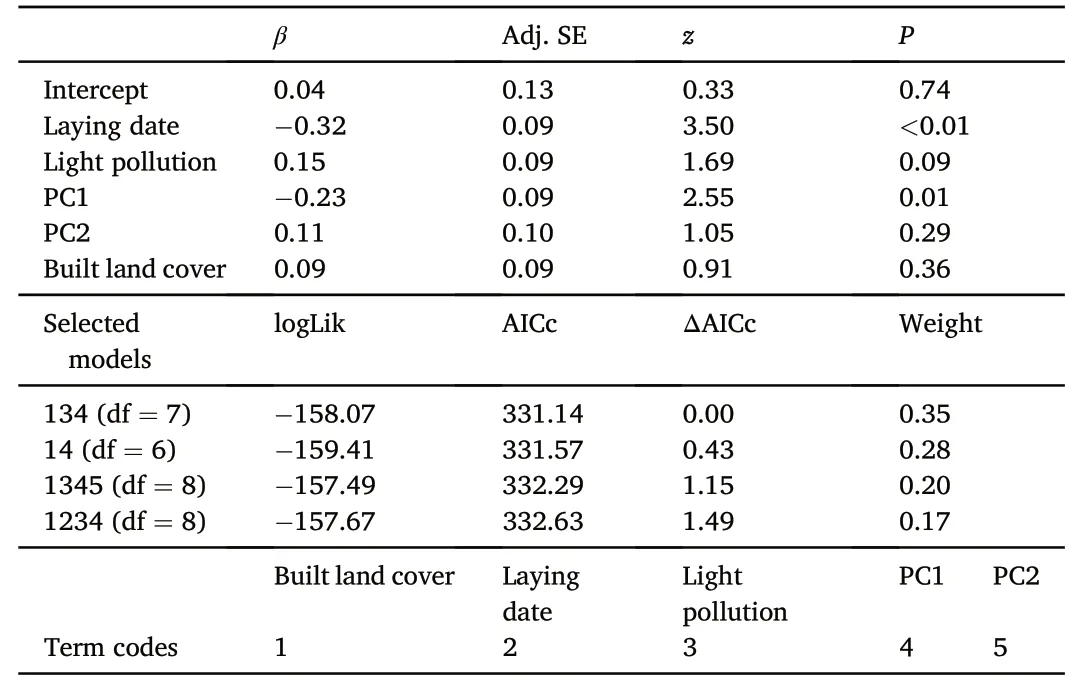

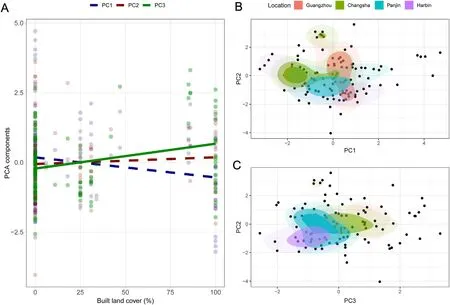

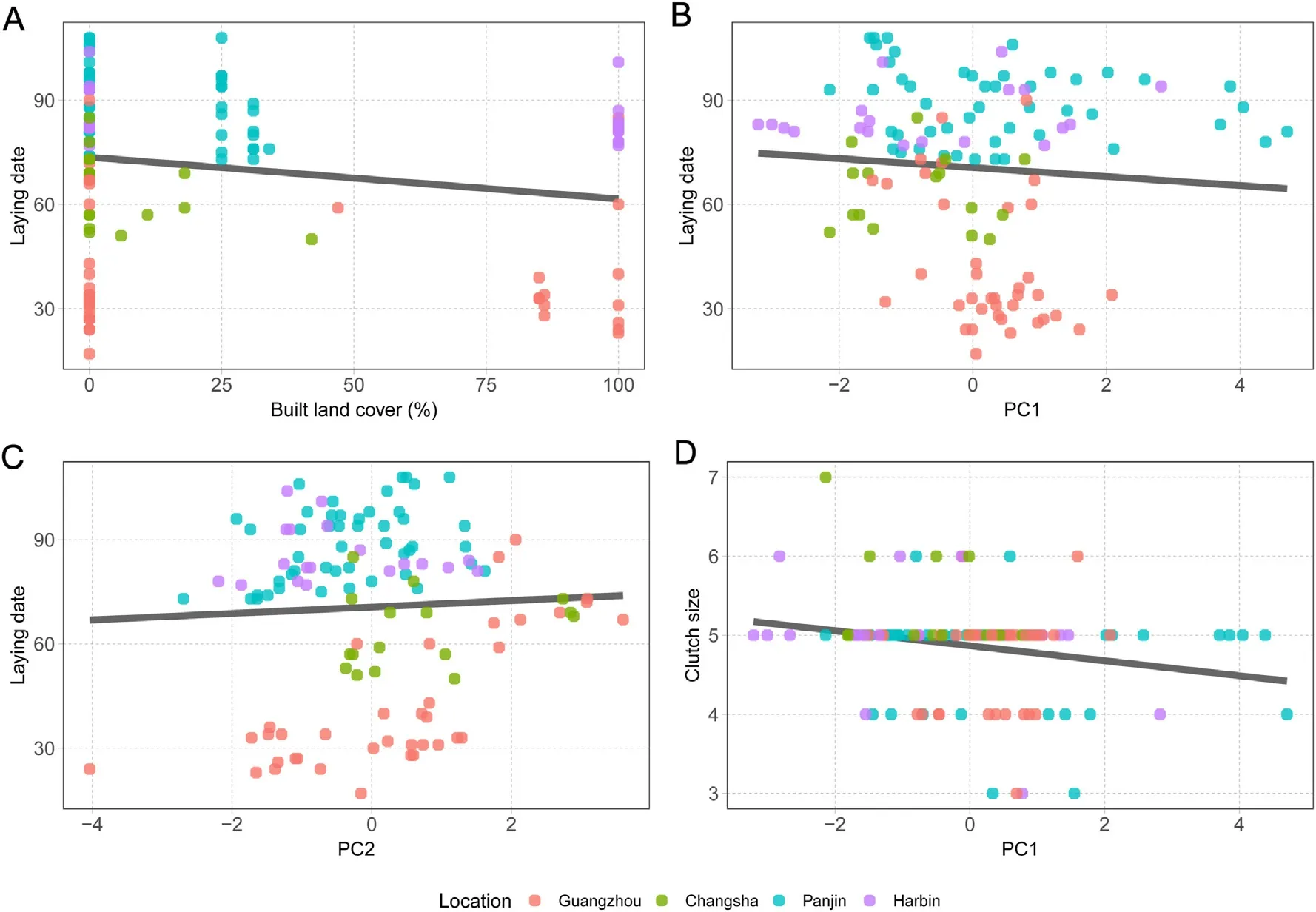

After accounting for variability in latitude and longitude by employing a linear correlation structure based on these variables,normalized laying date correlated negatively with landscape urbanization and PC1 and positively with PC2,while it did not correlate with PC3 or artificial light pollution at night(Table 2;Fig.4A-C).After accounting for these fixed effects,locations showed significant differences in normalized laying dates (F3,116=2.92,P=0.04),yet only birds in Harbin started breeding significantly later than in Changsha (P=0.03,95% CI=0.05-1.47).Following the same procedure,clutch size correlated negatively with laying date and PC1 in the averaged model and showed a non-significant positive relationship with artificial lightpollution at night,yet it did not correlate significantly with landscape urbanization,PC2 or PC3 (Table 3;Fig.4D).After accounting for these fixed effects,locations showed significant differences in clutch size(F3,116=3.51,P=0.02),yet only Barn Swallows from Changsha showing significantly larger clutch sizes than birds from Guangzhou (P<0.01,95% CI=0.17-1.54).Finally,the averaged model for breeding success only retained landscape urbanization,yet the relationship was nonsignificant (Table 4).Locations showed no significant differences in breeding success(F3,116=0.56,P=0.65).

Table 1 Principal Component Analysis(PCA)on a correlation matrix using seven environmental factors recorded in 120 nests of Barn Swallows(Hirundo rustica)during 2018 as dependent variables.

Table 2 Linear Mixed-Effects model fit by Restricted Maximum Likelihood using normalized laying date(date on which first egg was laid measured as Ndays since March 1st) as dependent variable and built land cover (built area within 1 km2 around nests),the three components from our PCA,and artificial light pollution at night as independent variables.

Table 3 Conditional averaged model based on Akaike Information Criterion corrected by sample size(AICc) after retaining results of conditional averages of the selected models (ΔAICc <2).

Table 4 Conditional averaged model based on Akaike Information Criterion corrected by sample size(AICc)after retaining results of conditional averages of the selected models (ΔAICc <2).

Fig.3.(A) Linear relationships between landscape urbanization,measured as % of built land cover (built area within 1 km2 around nests),and three components(PC1,PC2 and PC3;see Table 1) with eigenvalues higher than 1 extracted from a principal component analysis on seven environmental factors in 120 nests of Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) collected during 2018.Dashed lines represent non-significant relationships.(B) Two-dimensional kernel density estimation based on PC1 and PC2 by study location.The shaded areas depict the inferred probability density function in the two-dimensional space with darker colors meaning a higher probability to find a nest within these component coordinates.(C) Following the same approach,two-dimensional kernel density estimation based on PC2 and PC3.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend,the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4.Discussion

4.1.Coping with detrimental effects of urbanization and related environmental factors

Across a wide geographical area spanning 22°of latitude and 9°of longitude in China,we recorded the degree of,and environmental differences associated with,landscape urbanization and how these influenced life-history traits,such as laying date and clutch size,of open cup nesting Barn Swallows.We found that urban nests were exposed to higher diurnal noise and longer times without receiving diurnal light than rural nests.The fact that we did not record differences in other environmental factors suggests that urban birds were selecting nesting sites concealed to a similar or a greater extent than rural birds,ameliorating potential negative effects of these factors.Behavioural adaptations to urban life have previously been reported across multiple taxa (Sol et al.,2013),including nest site choice.For instance,previous studies have reported changes associated with urbanization in nesting sites of European Greenfinches (Carduelis chloris) (Kosiński,2001) or Black-billed Magpies (Pica hudsonia) (Jokimäki et al.,2017;Xu et al.,2020).Our study expands on this issue by examining the relationships between urbanization and relevant environmental factors in Barn Swallow nests which have been shown to influence parental investment and fitness (Ambrosini et al.,2006;Ambrosini and Saino,2010;de Satgé et al.,2019).

Fig.4.Linear relationships between (A) built land cover (built area within 1 km2 around nests) and laying date (date on which first egg was laid measured as Ndays since March 1st),(B) PC1 and laying date,(C) PC2 and laying date,and (D) PC1 and clutch size (Neggs).Data collected from 120 nests of Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica)collected during 2018 at four locations in China(Guangzhou,Changsha,Panjin and Harbin),data points from each location are depicted with different colors.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend,the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

We found that birds experiencing high nocturnal noise and exposure to intense diurnal light (PC1),laid small clutches regardless of urbanization intensity.This result is in line with previous studies showing,for instance,the pervasive negative effects of single environmental factors such as noise pollution(Schroeder et al.,2012;Strasser and Heath,2013;Huet des Aunay et al.,2017).Conversely,our results show that landscape urbanization was only significantly related to earlier laying dates,while urban and rural birds showed similar clutch sizes and breeding success.In contrast to a previous study employing a similar approach(Sprau et al.,2017),this pattern suggests that exposure to these environmental factors-rather than landscape urbanizationper se-is linked to reduced investment in reproduction by females.In light of these results and previous studies(Møller,2010;Teglhøj,2017),Barn Swallows seemed able to adapt to increasingly urbanized environments.

4.2.The effect of urbanization and environmental factors on laying date

Similar to our results,previous research has recorded earlier laying dates in urban than in non-urban environments(e.g.Chamberlain et al.,2009;Caizergues et al.,2018;de Jong et al.,2018;Seress et al.,2018,2020;but see Huchler et al.,2020).We also recorded a negative relationship between laying date and nest exposure to nocturnal noise and diurnal light (PC1).This is,to our knowledge,a novel result as,for instance,studies focusing on noise pollution have recorded no effect(Halfwerk et al.,2011) or a positive relationship between noise and laying date (Injaian et al.,2018).Interestingly,we found a positive correlation between temperature around the nests(PC2)and laying date,although temperature differences were unrelated to landscape urbanization.This is quite surprising as there is evidence that global warming is producing earlier laying dates in multiple bird species at both national(Crick et al.,1997) and regional scales (Both et al.,2004).Overall,our findings suggest that,urbanization,exposure to environmental factors and increased temperatures,can exacerbate or counteract each other and simultaneously influence the onset of the breeding season in a complex fashion.If an early laying date is crucial for fitness,as is the case of Barn Swallows (Grüebler and Naef-Daenzer,2008;Raja-aho et al.,2017),urban areas in which temperature increases are particularly intense,e.g.,highly urbanized cities in temperate regions of the USA (Imhoff et al.,2010),or areas in which birds are more exposed to environmental factors,may thus act as an ecological trap.This risk would be particularly important for species that are relatively indifferent to urbanization,such as our study species,and are particularly sensitive to phenological changes,such as migratory birds (Møller et al.,2008;Jones and Cresswell,2010).

4.3.The effect of urbanization and environmental factors on clutch size and breeding success

We found that clutch size correlated negatively with laying date and exposure to environmental factors(PC1);larger clutch sizes were laid by early breeders in areas less exposed to the potential detrimental effects of noise and low nocturnal temperatures,and high insolation.Our results suggest that pairs breeding later in the season were more exposed to the detrimental effects of environmental factors and may have therefore invested less energy in reproduction.Seasonal declines in reproductive output have been observed in many bird species such as Barn Swallows(Ambrosini et al.,2006)and Blue Tits(Cyanistes caeruleus;García-Navas and Sanz,2011),and are attributed either to a seasonal decline in the phenotypic quality of parents or to a seasonal deterioration of environmental conditions(Verhulst and Nilsson,2008),relationships that we are not able to tease apart in our study.We also recorded a non-significant positive relationship between artificial light pollution at night and clutch size.Our results,and others,suggest that light pollution may facilitate additional food resources to insectivorous birds(Senzaki et al.,2020;Wang et al.,2021).Finally,we did not record any significant effects on breeding success in our spatially explicit models accounting for variation in latitude and longitude,and no differences between study locations.These data exemplify how adaptable Barn Swallows are to such different environmental conditions,showing negligible fitness differences from densely urbanized city centres in the subtropical South to remote rural areas in the cold North.

4.4.Caveats

We must acknowledge certain limitations of our study.In addition to other sources of human disturbance,exposure to multiple environmental factors and changes in food availability explain patterns of species persistence and fitness gradients (McKinney,2008;Schlesinger et al.,2008;Seress et al.,2018,2020).Unfortunately,we did not have data on diet composition,which clearly merits further attention.Moreover,we conducted our study over a single breeding season,and certain effects of exposure to environmental factors or landscape features could change across years.For instance,the heat island effect may significantly increase across time within and between breeding seasons (Zhang et al.,2010),which may affect prey phenology(e.g.,Visser et al.,2006)and in return exacerbate its effect over breeding birds.Southern Barn Swallows are smaller and have longer breeding seasons than northern birds(Pagani-Núñez et al.,2016;Zhao et al.,2021),but since we were unable to take morphological measurements,or systematically record all breeding attempts in so many locations,we are unable to provide a more complete picture of the effect on fitness of exposure to urbanization and multiple environmental factors.Aerial insectivores and other typically urban taxa such as the House Sparrow are declining worldwide (Summers-Smith,2003;De Laet and Summers-Smith,2007;Nebel et al.,2010).Our study is,therefore,helpful in narrowing potential drivers of these declines.Further research is needed to determine how the combined effects of the environmental factors studied here interact with food availability in determining patterns of species’ survival and extinction across urbanization gradients.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the laws and regulations of the People’s Republic of China.

Availability of data

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: E.P.N.,X.X.&R.J.S.;Fieldwork: Y.Z.,Yu Liu,E.P.N.,G.P.,L.S.,X.L.,Z.Z.,Y.C.Data curation: Y.Z.&E.P.N.;Formal analysis:E.P.N&Y.Z.;Funding acquisition:E.P.N.,X.X.&R.J.S.;Writing:E.P.N.with contributions from all authors.All authors revised,read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Wangming Li,Xinyuan Pan,Dan Liang,Zhenming Yang,Xia Zhan,Minghai Huang,Chengyi Liu,Qingxia Li,Yujun Feng,Shi Li,Wei Chen,Xuan Wu,Yuhao Sha,Xiaomeng Zhao,Yajie Que,Xiaopeng Tan,Lei Zhao,Ruihan Chen,Licheng Yuan,and Zi Yun for their help in the field.We are also very grateful to several anonymous reviewers who provided helpful comments on previous versions of the manuscript.This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(31770454 to E.P.N.,X.X.and R.J.S.).

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avrs.2022.100048.

杂志排行

Avian Research的其它文章

- Functional and phylogenetic structures of pheasants in China

- Thermoregulatory function and sexual dimorphism of the throat sack in Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris) across Africa

- Distribution pattern and driving factors of genetic diversity of passerine birds in the Mountains of Southwest China

- Multiple lines of evidence confirm that the critically endangered Blue-crowned Laughingthrush(Garrulax courtoisi)is an independent species

- Corrigendum to “Multiple lines of evidence confirm that the critically endangered Blue-crowned Laughingthrush (Garrulax courtoisi) is an independent species” [Avian Res.13 (2022) 100022]

- Altitudinal seasonality as a potential driver of morphological diversification in rear-edge bird populations