Relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function in outpatients with dementia and mild cognitive impairment compared with community residents without dementia

2022-09-06AiHirasawaKumikoNagaiTaikiMiyazawaHitomiKoshibaMamiTamadaShigekiShibataKoichiKozaki

Ai Hirasawa, Kumiko Nagai, Taiki Miyazawa, Hitomi Koshiba, Mami Tamada, Shigeki Shibata,✉, Koichi Kozaki

1. Department of Health and Welfare, Faculty of Health Sciences, Kyorin University, Tokyo, Japan; 2. Department of Geriatric Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Kyorin University, Tokyo, Japan; 3. Department of Health and Sports Science, Faculty of Wellness, Shigakkan University, Aichi, Japan

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND It is unclear whether the dementia patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) and mixed dementia (MIX, including AD and VaD) would have more developed arterial stiffness as compared with local residents without dementia. The aim of this study was to assess arterial stiffness and cognitive function in different types of dementia patients [AD, VaD, MIX and mild cognitive impairment (MCI)] and community residents without dementia.METHODS This was a single-center, cross-sectional observational study. We studied a cohort of 600 elderly outpatients with a complaint of memory loss, who were divided into four groups (AD, VaD, MIX and MCI). In addition, they were compared with 55 age-matched local residents without dementia (Controls). We assessed arterial stiffness by brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity(baPWV) and the global cognitive function by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).RESULTS The baPWV was higher in AD, VaD and MIX than in MCI and in Controls (P < 0.05). The baPWV was higher in MCI than in Controls (P = 0.021), while MMSE were compatible between them (P = 0.119). The higher baPWV predicted the presence of AD, VaD, MIX and MCI with the odds ratio of 6.46, 8.74, 6.16 and 6.19, respectively. In contrast, there were no difference in baPWV among three different types of dementia (P = 0.191). The linear relationship between baPWV and MMSE was observed in the elderly with MMSE ≥ 23 (R = 0.452, P = 0.033), while it was not in dementia patients (MMSE < 23).CONCLUSIONS The findings suggest that MCI and dementia patients have stiffer arteries as compared with age-matched local residents, although global cognitive function may be comparable between MCI and the local residents.

The development of arterial stiffness is caused by hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, obesity and smoking, and is markedly affected by aging. The occurrence of cardiovascular diseases and stroke increases as the population ages, at least, due to the development of arterial stiffening with aging. Similarly, cognitive impairment is closely related to the arterial stiffening with aging.

It is well established that arterial stiffness is an independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, particularly of stroke and coronary heart disease.[1-4]Recent evidence indicates that systemic arterial stiffness is also related to cognitive decline in general population based on both cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiological studies. For example, the recent systematic reviews and meta-analysis demonstrated that higher pulse wave velocity (PWV)predicted poorer cognitive performance and a steeper cognitive decline.[5-9]Moreover, it was indicated that carotid-femoral PWV was a strong predictor of cognitive decline in the elderly, independently of other risk factors that could also affect cognition, such as HT, age or education.[10,11]Similarly, an association between brachial-ankle PWV (baPWV) and poor cognitive function after adjustment for age, education and indices of atherosclerosis was observed in the Japanese general population.[12,13]

The number of dementia patients increases as the population ages. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) are common types of dementia, both of which are associated with aging. The pathologic features of AD are neurofibrillary tangles and brain beta-amyloid deposition.[14-17]On the other hand, VaD is a type of dementia caused by cerebrovascular disorder, and its underlying pathology is heterogeneous, in which cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is considered to be the most common type.[18-20]The SVD dementia that develops as a result of arteriolosclerosis is called subcortical VaD,which is divided into two types: multiple lacunar infarct dementia when lacunar infarcts are the main cause, and Binswanger’s disease when white matter lesions are the main cause. In addition, complications and continuity between VaD and AD were noted, and mixed dementia (MIX) is the focus of attention. The pathophysiological feature of the MIX is characterized by having the features of both AD and VaD, and its prevalence is presumed to be significant, approximately 20%-40%.[21]Thus, it is likely that patients with AD, VaD and MIX would have more developed atherosclerosis as compared with local resident without dementia. However, it is still unclear whether dementia patient with AD, VaD and MIX would have more developed central arterial stiffness as compared with local peers.

The aim of the present study was to clarify the relationship between arterial stiffness, and different types of dementia patients (AD, VaD and MIX) and community-dwelling elderly without dementia.

METHODS

Study Population

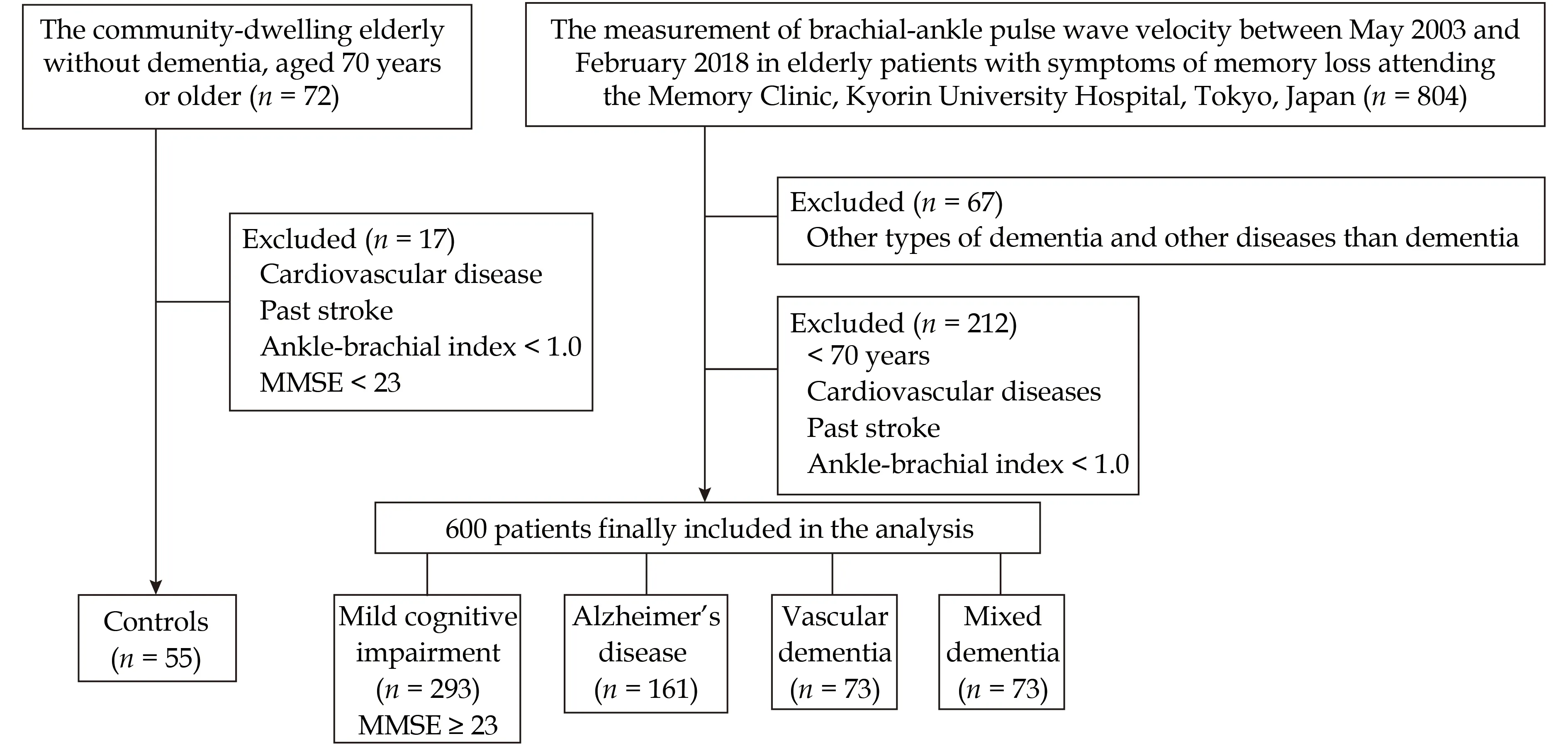

This was a single-center observational study. We studied a cohort of 600 outpatients with complaint of memory loss at age of 70 years and over, who were divided into four groups; three types of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (AD, VaD and MIX: MMSE < 23; MCI: MMSE ≥ 23). In more detail,between May 2003 and February 2018, we enrolled 804 elderly patients with symptoms of memory loss attending the Memory Clinic, Kyorin University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. The other types dementia than AD, VaD and MIX such as dementia with Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinsonian dementia, normal pressure hydrocephalus, etc. and cognitive impairment caused by diseases other than dementia such as endocrine and metabolic disorders, psychiatry diseases, etc. were excluded (n = 67,Figure 1). In addition, we excluded patients aged <70 years, stroke except for lacuna or/and cerebral microbleeds, coronary artery diseases, significant valvular diseases, and stenosis or/and occlusion of a lower extremity artery [ankle-brachial index (ABI) <1.0] (n = 212, Figure 1). The total of 600 patients were finally included for the analysis. Patients were divided into four groups based on the types of dementia diagnosed by the physicians specialized for geriatric medicine and dementia, and consequently 161 elderly patients were diagnosed with AD, 73 patients were VaD, 73 patients were MIX, and 293 patients were MCI, respectively. AD was diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition criteria, and VaD was diagnosed using National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Association International pour la Recherché et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NIDNS-AIREN) criteria. Clinical evaluation was based on medical interview, cognitive function tests, and diagnostic imaging using brain magnetic resonance imaging and single-photon emission computed tomography. Although the neuropathologic classification of VaD by NIDNS-AIREN has six categories; multiple-infarct, strategic single-infarct,SVD, hypoperfusion, hemorrhagic and others, the present study address only the VaD caused by SVD.The reason why the SVD dementia was selected in the present study was to avoid the complexity due to heterogeneity in etiology and clinical presentation of VaD. For example, brain damage varies depending on the region of infarction and/or hemorrhage, and brain hypoperfusion is caused by variety of clinical conditions, while the SVD dementia including multiple lacunar and/or Binswanger’s disease is homogenous in etiology and clinical presentation relative to the other VaD categories. The MIX was diagnosed as having both features of AD and the SVD dementia. The MCI was diagnosed as cognitively impaired but not demented based on cognitive function tests (MMSE ≥ 23) and clinical symptoms. In addition, to compare the patients with community-dwelling elderly, we enrolled 72 local residents who were aged 70 years or older without diagnosis of dementia. In this enrollment, we excluded patients with past cerebral infarction except for lacuna or/and cerebral microbleeds, coronary artery diseases, significant valvular diseases, stenosis or/and occlusion of a lower extremity artery (ABI < 1.0)and MMSE < 23 (n = 17, Figure 1). Eventually, 55 participants were enrolled as local non-demented controls (Controls).

Figure 1 Summary of participants screening and enrollment. MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination.

This study protocol conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine at Kyorin University, Tokyo, Japan (No.179). All patients gave written informed consent to this study after the details of the study were explained to each patient.

Measurements

The global cognitive function (MMSE) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were evaluated by the trained psychologists.[22,23]

Arterial stiffness was noninvasively evaluated by baPWV in the supine position using the commercially available automated device (form PWV/ABI,OMRON-COLIN, Japan). The pulse wave transit time was determined by the average of ten cardiac beats.The brachial-ankle travel distance of pulse wave was estimated from patient body height. The baPWV was automatically calculated with the distance divided by the transmitted time between brachial and ankle arteries. The average value of left and right baPWVs was used for data analysis. In our laboratory, the typical error as a coefficient of intra-observer variation in measurement of baPWV was 2.0%,and changes in mean were 0.2% (n = 274).[24]

Statistical Analysis

All results were expressed as mean ± SD. The analysis of variance and the Pearson’s chi-squared test were used for quantitative and qualitative variables,respectively. The baPWV values among five groups(AD, VaD, MIX, MCI and Controls) were compared by using the analysis of covariance, including age,gender, DM, hyperlipidemia (HL), HT and smoking as a covariate. Multiple comparisons were performed using Bonferroni test to compare baPWV among five groups. We calculated the area under the curve after constructing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The ROC curves illustrate the sensitivity and specificity of the baPWV to distinguish dementia (AD, VaD, MIX, AD + VaD + MIX or MCI)and Controls (Figure 2). The baPWV was divided to high or low by the optimal cutoff value of each type of dementia determined from highest sensitivity and specificity of ROC curve. The binomial logistic regression analysis model was used to assess the relationship between baPWV and the presence of dementia, adjusted for age and gender, DM, HL, HT and smoking. The simple and multiple linear regression analysis were performed to assess the relationship between baPWV and MMSE, adjusted for age and gender, DM, HL, HT and smoking. Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 2 The receiver operating characteristic curves illustrate the sensitivity and specificity of the brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity to distinguish dementia (AD, VaD, MIX, AD + VaD +MIX or MCI) and Controls. The area under the curve was 0.775,0.840, 0.873, 0.814 and 0.697 in AD, VaD, MIX, AD + VaD + MIX and MCI, respectively. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; MIX: mixed dementia; VaD: vascular dementia.

RESULTS

The clinical characteristics of this study population were summarized in Table 1. There were 655 elderly individuals with a mean age of 79 ± 5 years and 60.6% (n = 397) were female. Controls and MCI were slightly younger than AD, VaD and MIX (P < 0.001).MIX and VaD showed higher pulse pressure as compared with Controls (P < 0.05) and MCI (P < 0.01).AD showed higher pulse pressure than MCI (P <0.01). The prevalence of DM, HL, HT and smoking were observed in 9.6% (n = 63), 34.2% (n = 224), 51.9%(n = 340) and 26.0% (n = 170) of the whole population, respectively. The prevalence of HL was significantly higher in MCI, AD and MIX than in Controls (P < 0.05). The prevalence of HT was significantly higher in MCI, AD, VaD and MIX than in Controls (P < 0.05). The scores of MMES and IADL were significantly lower in AD, VaD and MIX patients than in MCI and in Controls (P < 0.001). MMSE and IADL were not different between MCI and Controls (P = 0.119 and P = 0.990, respectively).

The baPVW was significantly higher in AD (2360 ±750 cm/s), VaD (2473 ± 788 cm/s) and MIX (2605 ±807 cm/s) than in Controls (1762 ± 312 cm/s) and in MCI (2096 ± 524 cm/s) after adjustment with age,gender, DM, HL, HT and smoking (P < 0.001). In addition, the baPWV was significantly higher in MCI than in Controls (P = 0.021). In contrast, there were no significant difference in baPWV between different types of dementia (P = 0.191, Figure 3).

Table 1 Characteristics of the population.

Figure 3 The baPWV values of Controls, MCI, AD, VaD and MIX patients. The baPWV values among five groups (AD, VaD,MIX, MCI and Controls) were compared by using the analysis of covariance, including age, gender, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and smoking as a covariate. Multiple comparisons were performed using Bonferroni test to compare the baPWV values between two groups. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; baPWV: brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity; MCI: mild cognitive impairment;MIX: mixed dementia; VaD: vascular dementia.

The optimal cutoff values of AD, VaD, MIX, AD +VaD + MIX and MCI were 1987 cm/s, 1928 cm/s,1990 cm/s, 1987 cm/s and 1983 cm/s, respectively.The binomial logistic regression analysis was performed using the presence of dementia as a dependent variable and higher or lower baPWV based on the optimal cutoff values as an independent variable.Figure 4 shows odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) according to cutoff values (Figure 4A)and per 1 m/s increase in baPWV (Figure 4B) using binomial logistic regressions analysis to predict the presence of dementia with and without adjustment for age, gender, DM, HL, HT and smoking. The ORs of higher baPWV value to predict the presence of dementia were 8.84 (95% CI: 4.04-19.33), 12.34 (95% CI:5.32-28.62), 11.25 (95% CI: 4.88-25.94), 11.23 (95% CI:5.29-23.88) and 5.66 (95% CI: 2.67-11.99) in AD, VaD,MIX, all dementia (AD + VaD + MIX) and MCI, respectively. The ORs of that were 6.46 (95% CI: 2.74-15.25), 8.74 (95% CI: 3.54-21.53), 6.16 (95% CI: 2.30-16.52), 7.34 (95% CI: 3.25-16.58) and 6.19 (95% CI: 2.65-15.50) after adjustment for age, gender, DM, HL, HT and smoking, respectively (Figure 4A). The ORs of per 1 m/s increase in baPWV to predict the presence of dementia were 1.27 (95% CI: 1.16-1.39), 1.40(95% CI: 1.23-1.59), 1.47 (95% CI: 1.28-1.68), 1.32 (95% CI:1.21-1.45) and 1.21 (95% CI: 1.11-1.32) in AD, VaD, MIX,all dementia (AD + VaD + MIX) and MCI, respectively. The ORs of that were 1.24 (95% CI: 1.12-1.37), 1.32(95% CI: 1.16-1.51), 1.41 (95% CI: 1.21-1.63), 1.27 (95%CI: 1.15-1.41) and 1.21 (95% CI: 1.10-1.33) after adjustment for age, gender, DM, HL, HT and smoking(Figure 2).

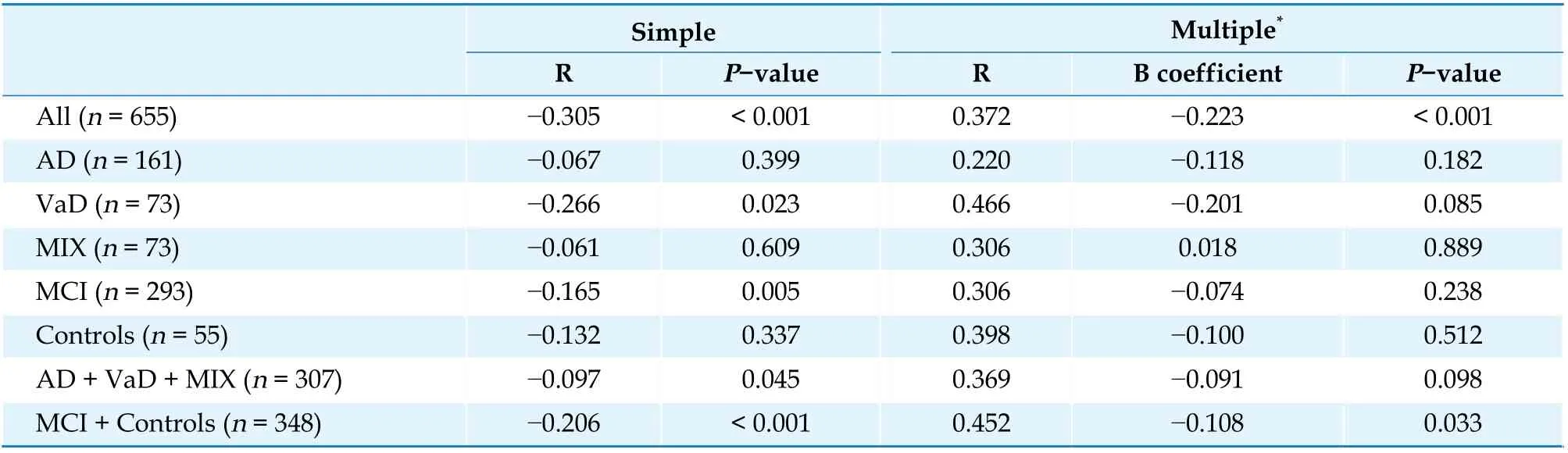

A simple linear regression analysis showed a negative linear relationship between baPWV and MMSE in VaD, MCI, AD + VaD + MIX, MCI + Controls and all population (Table 2). The relationship between baPWV and MMSE was significant in the MCI and in Controls (MMSE ≥ 23, R = 0.452, P = 0.033) and all population after adjustment for age, gender, DM,HL, HT and smoking, but not in the dementia patients (AD + VaD + MIX; MMSE < 23, R = 0.369, P =0.098, Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Figure 4 The OR and 95% CI of the baPWV value to predict the presence of dementia. The ORs are expressed as higher baPWV value (A) and per 1 m/s increase (B) in baPWV after adjustment for age gender, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and smoking status. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; baPWV: brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; MIX: mixed dementia; OR: odds ratio; VaD: vascular dementia.

Table 2 The simple and multiple linear regression analysis to assess the relationship between brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and Mini-Mental State Examination.

The present study for the first time assessed the relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function in a large population of elderly patients with a symptom of memory loss and communitydwelling elderly without dementia. The primary findings of the present study were as follows: (1) while the baPWV of dementia patients such as AD, VaD and MIX were higher than that of MCI and age-matched local residents, the baPWV was not different among AD, VaD and MIX patients; (2) baPWV was significant predictor for the presence of dementia not only in AD, VaD and MIX patients but also MCI patients. Intriguingly, despite global cognitive function (MMSE score) was not different between MCI patients and age-matched local residents, baPWV was significantly higher in the MCI patients than in the local residents; and (3) while lower cognitive function was related with higher arterial stiffness in the elderly with preserved cognitive function (MCI and Controls, MMSE ≥ 23), this significant relationship between cognitive function and arterial stiffness was not observed in the all dementia patients (AD + VaD +MIX, MMSE < 23).

Many cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have demonstrated the association between arterial stiffness and cognitive function in the community based studies,[5,8,12,25-31]and in the clinical research including outpatients.[25,30,32,33]The present study clarified the relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function in the Memory Clinic outpatients and compared those with age-matched local residents without dementia, and showed the significant linear relationship between baPWV and MMSE in all population after adjustment for age, gender, DM, HL,HT and smoking, consistent with majority of previous studies. As far as we know, the present study for the first time directly compared the outpatients with the age-matched local residents with focus on the relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function. The present findings revealed that elderly dementia patients including MCI had stiffer arteries as compared with community-dwelling elderly people without dementia. Notably, the elderly MCI patients had stiffer arteries as compared with the age-matched local residents without dementia while there was no significant difference in the global cognitive function between them. This finding suggests that arterial stiffness is a useful objective marker for identifying subjective symptoms of cognitive impairment as compared with commonly used clinical cognitive function test of MMSE, because it is likely the different characteristics between MCI patients and the age-matched controls in the present study was the presence or absence of subjective cognitive symptoms that bring them to Memory Clinic. However, we need to carefully interpret the findings as the present study was the cross-sectional.

The chronic cerebral hypoperfusion, which is one of representative pathophysiologic changes in VaD,was reported to be closely related with arterial stiffness.[34]Moreover, the previous study reported that central elastic artery stiffness is inversely associated with cerebral perfusion in deep subcortical frontal white matter in middle-aged individuals.[35]The systematic review showed the association between development of arterial stiffness and severity of cerebral SVD (e.g., cerebral white matter hyperintensities, cerebral microbleeds or cerebral infarcts).[6]Moreover, it was known that VaD was exacerbated by cerebrovascular events and arterial stiffness was an independent risk factor for cerebrovascular diseases.[36]Taken together, there is no doubt that VaD is closely related with arterial stiffness, consistent with the present findings. On the other hand, the previous study has reported that hippocampal atrophy,which is a representative morphological change observed in AD patients, was not correlated with arterial stiffness in elderly adults with HT.[37]However,two-year longitudinal study demonstrated that increases in the brain beta-amyloid deposition with aging was strongly related with arterial stiffness in nondemented elderly adults.[38]Therefore, the development of arterial stiffness is likely to be a significant risk factor not only for VaD but also for AD,given that the brain beta-amyloid deposition is the common pathologic feature of AD. Consistent with these previous studies focusing on the pathophysiology of dementia, the present study indicated that baPWV was a significant factor to predict the presence of AD, VaD and MIX after adjustment for age,gender, DM, HL, HT and smoking, although it was not different between the different types of dementia.

As far as we know, there has been only one study which assesses arterial stiffness in outpatients with diagnosed dementia. Our findings are consistent with this previous study by Hanon, et al.[32]that showed an independent correlation between arterial stiffness and cognitive impairment in the outpatients with symptoms of memory loss including those diagnosed with MCI, AD or VaD. Importantly, the present study extended this previous study in several aspects by comparing dementia patients with local community residents without dementia, including patients diagnosed with MIX type of dementia, and enrolling large population of patients which enabled to assess the characteristics not only in the whole study population but also within the different types of dementia. In the present study, lower cognitive function was not significantly related with higher arterial stiffness within each type of dementia patients and all dementia patients. This finding indicates that arterial stiffness may not be a significant factor to assess the severity of the cognitive impairment in the elderly dementia patients with MMSE <23, even though it is useful to predict the presence of dementia. In other words, arterial stiffness may play a more important role in the early stage of dementia development as compared with the late stage.However, again, we need to be careful as the present study was the cross-sectional.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations in the present study.Firstly, the present study focused on only specific population of VaD; the SVD dementia. Thus, our findings are not likely to be applied for general population of VaD. Secondly, arterial stiffness was evaluated by baPWV using the automated device. Since baPWV reflects the stiffness of both central and peripheral arteries, the present findings could not be exclusively attributable to central arterial stiffness.Last but not least, the effects of internal medications were not considered in the present study, which may have influenced on the whole results.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the present study for the first time evaluated arterial stiffness and cognitive function in a large population of elderly outpatients with a symptom of memory loss, and compared those with agematched local community residents without dementia. The findings suggest that arterial stiffness is a significant predictor not only for the presence of dementia but also for the presence of MCI, while it is not different among the different types of dementia.Moreover, evaluation of arterial stiffness may be more clinically important in the early stage of cognitive impairment progression as compared with the late stage of advanced dementia, although future longitudinal studies would be warranted in this aspect.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research Grant (15K08931 & 17K18088),and the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant(H28 Ninchisho-Ippan-003) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors appreciate the time and effort spent by all volunteer subjects.

杂志排行

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Effect of uninterrupted dabigatran or rivaroxaban on achieving ideal activated clotting time to heparin response during catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation

- Inflammation-based different association between anatomical severity of coronary artery disease and lung cancer

- Long-term outcome of percutaneous or surgical revascularization with and without prior stroke in patients with threevessel disease

- Serum triglycerides concentration in relation to total and cardiovascular mortality in an elderly Chinese population

- The predictive value of triglyceride-glucose index for in-hospital and one-year mortality in elderly non-diabetic patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation successfully treated massive right ventricular myocardial infaction with aneurysm