Secondary sclerosing cholangitis after critical COVlD-19: Three case reports

2022-09-01JuanMayorquAguilarAldoLaraReyesLuisAlbertoRevueltaRodrguezNayelliFloresGarcAstridRuizMarginMarcoAntonioJimnezFerreiraRicardoUlisesMacasRodrguez

Juan M Mayorquín-Aguilar, Aldo Lara-Reyes, Luis Alberto Revuelta-Rodríguez, Nayelli C Flores-García, Astrid Ruiz-Margáin, Marco Antonio Jiménez-Ferreira, Ricardo Ulises Macías-Rodríguez

Juan M Mayorquín-Aguilar, Aldo Lara-Reyes, Luis Alberto Revuelta-Rodríguez, Nayelli C Flores-García, Astrid Ruiz-Margáin, Ricardo Ulises Macías-Rodríguez, Department of Gastroenterology,Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City 14080,Mexico

Marco Antonio Jiménez-Ferreira, Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Mé dicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City 14080, Mexico

Abstract BACKGROUND The global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused more than 5 million deaths. Multiorganic involvement is well described, including liver disease. In patients with critical COVID-19, a new entity called "post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy" has been described.CASE SUMMARY Here, we present three patients with severe COVID-19 that subsequently developed persistent cholestasis and chronic liver disease. All three patients required intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, and broad spectrum antibiotics due to secondary infections. Liver transplant protocol was started for two of the three patients.CONCLUSION Severe COVID-19 infection should be considered a potential risk factor for chronic liver disease and liver transplantation.

Key Words: SARS-CoV-2; Persistent cholestasis; Liver chemistry; Hypoxic cholangiopathy; Case report

lNTRODUCTlON

The global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused more than 5100000 deaths worldwide, and as it grows, the knowledge of the disease as well as the discovery of new complications increases. Up to 30% of patients with COVID-19 present with abnormal liver chemistry during the course of the disease[1]; this can occur due to the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme II in cholangiocytes, a shared mechanism responsible for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2(SARS-CoV-2) entry into the cell. While most patients with COVID-19 develop mild and transient elevation of aminotransferases, in patients with critical disease requiring invasive mechanical ventilation and management in the intensive care unit (ICU), a new entity called “post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy” has been described, with only few cases reported to date[2].

Here, we present three patients with severe COVID-19, who subsequently developed persistent cholestasis and chronic liver disease.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

Case 1:A 45-year-old male presented to the emergency department of our hospital complaining of malaise, cough, fever, and progressive dyspnea.

Case 2:A 52-year-old male presented to the emergency department of our hospital with severe dyspnea and a positive real-time PCR (RT-PCR) SARS-CoV-2 test.

Case 3:A 46-year-old woman presented to the emergency department of our hospital complaining of malaise, headache, cough, fever, and progressive dyspnea.

History of present illness

Case 1:Patient´s symptoms started 10 d before hospital admission, with dyspnea at rest as the main complaint at admission.

Case 2:Patient’s symptoms started 7 d before his admission, and included malaise, cough, fever, and progressive dyspnea. Two days before admission, the patient presented with nausea, emesis, noninflammatory diarrhea, and dyspnea at rest.

Case 3:Patient´s symptoms started 13 d before admission, including cough, malaise and headache.During this time, a positive RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 test was obtained and she received symptomatic treatment with acetaminophen. Forty-eight hours before admission, she presented with persistent fever and resting dyspnea.

History of past illness

Case 1:Patient’s history was relevant for longstanding type 2 diabetes mellitus, systemic arterial hypertension, and chronic kidney disease KDIGO III. No history of hepatic disease was reported.

Case 2:Patient’s history was relevant for chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. No history of hepatic disease was reported.

Case 3:Patient’s history was relevant for history of chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. No history of hepatic disease was reported.

Personal and family history

No SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was available at the time of presentation. Family history was unremarkable in all three patients.

Physical examination

Case 1:Physical examination was relevant for oxygen saturation (SpO2) measured by pulse oximeter of 52%, tachypnea, respiratory distress, and crackles on chest auscultation.

Case 2:Physical examination was relevant for SpO2 measured by pulse oximeter of 50%, tachypnea,temperature of 37.8 °C, respiratory distress, and crackles on chest auscultation. Bilateral lower extremity edema was present.

Case 3:Physical examination was relevant for SpO2 measured by pulse oximeter of 80%, tachypnea,and crackles on chest auscultation.

Laboratory examinations

Case 1:At admission, blood tests showed lymphopenia, D-dimer 1093 ng/mL, ferritin 1436 ng/mL,creatinine 8.8 mg/dL and normal liver chemistry. SARS-CoV-2 infection was subsequently confirmed by RT-PCR, and the patient required invasive mechanical ventilation due to respiratory failure type 1[partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio of 80].

Case 2:At admission, blood tests showed lymphopenia and elevated inflammatory blood markers.Liver chemistry was normal.

Case 3:Initially, her liver chemistry was normal and elevated inflammatory blood markers were reported. After 72 h of admission, she developed severe hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 91) requiring mechanical ventilation and admission to the ICU.

Imaging examinations

Chest computed tomography (CT) was performed in all cases, which showed peripheral, bilateral ground glass opacities consistent with severe pulmonary involvement (> 50%) secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Further evolution and diagnostic work-up

Case 1:During hospitalization after 33 d of stay in the ICU, the patient required sedation with midazolam, fentanyl, and ketamine, high positive end-expiratory pressure (up to 20 cm H2O) and use of norepinephrine (maximum dose of 0.45 µg/kg/min). In addition, he was treated with meropenem,vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and co-trimoxazole due to blood and tracheal aspirate cultures yieldingEnterobacter cloacae, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia,andKlebsiella pneumoniae.Finally, the patient developed gastrointestinal bleeding caused by duodenal ulcers and required hemodialysis for acute renal failure and metabolic acidosis.

Interestingly, during his stay in the ICU, liver chemistry showed a cholestatic pattern (R factor of 0.7)with an isolated and persistent increase in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels. The initial diagnostic workup, included abdominal ultrasound and CT, which did not show bile duct dilatation. The patient eventually improved his clinical conditions, including liver chemistry showing a decrease in ALP levels,extubation on the 35thday, and discharged 42 d after his initial presentation at the endoscopy.

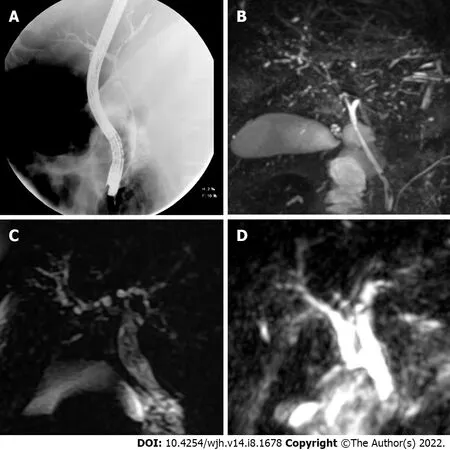

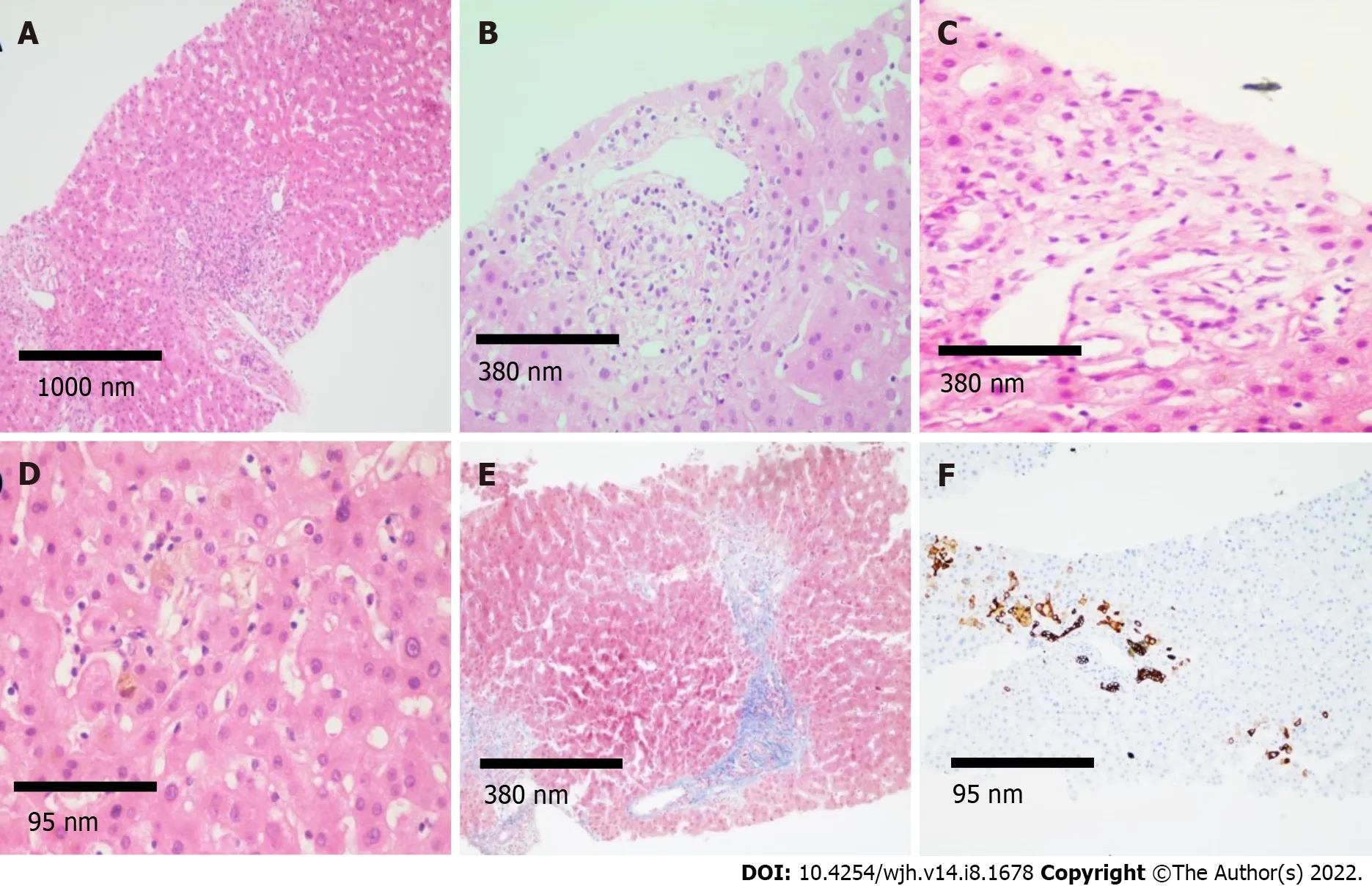

Six weeks after discharge, he developed jaundice, pruritus, and sleep disturbances. New biochemical parameters reported a total bilirubin (TB) 5.8 mg/dL, direct bilirubin (DB) 3.4 mg/dL, and ALP 1328 U/L. Interestingly, hypercholesterolemia developed in the patient, with peak levels reaching 1920 mg/dL (normal < 200 mg/dL). A contrast-enhanced CT scan showed intrahepatic bile duct dilatation and a common bile duct diameter of 8 mm with biliary sludge. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) was performed and cholangiography confirmed dilation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, a sphincterotomy and balloon sphincteroplasty were also performed, obtaining a bile duct stone, bile duct casts and dark bile, ultimately a biliary plastic stent was placed (Figure 1A).Despite this, there was no improvement in liver chemistry, showing a persistent elevation of ALP levels(> 15 × upper limit of normal); therefore, magnetic resonance cholangiography was performed, showing multiple areas of stenosis in the distal intrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 1B). Differential diagnosis of liver chemistry abnormalities included autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC), immunoglobulin G4-related disease, viral hepatitis, and drug-induced liver injury(DILI), all of which were ruled out by negative specific antibodies, Ig, and liver biopsy. Percutaneous liver biopsy showed findings consistent with intracanalicular cholestasis, portal inflammation, ductular reaction, and moderate portal fibrosis (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Sclerosing cholangitis imaging findings. A: Cholangiogram showed dilatation of the common bile duct and its intrahepatic branches in the first case; B: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated multiple short stenosis of the intrahepatic bile ducts; C and D: In the second and third case, the MRI showed multiple stenosis of the intrahepatic bile duct.

Figure 2 Histological findings. A: Histological sections of the liver (magnification 4 ×) stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) showing mixed inflammatory infiltrate in portal spaces; B and C: H&E (magnification 10 ×) showing regenerative changes and swelling of cholangiocytes, as well as presence of inflammatory infiltrate in the portal space vein and hepatic artery; D and E: Intracanalicular and cytoplasmic cholestasis is observed predominantly in space 3, fibrosis in portal and periportal space (magnification 40 × and 10 ×, respectively); F: Immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) demonstrating CK7 metaplasia in hepatocytes and ductular reaction (magnification 40 ×).

Case 2:He required invasive mechanical ventilation with intermittent prone positioning due to respiratory failure type 1 (PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 73). On day 28 of ICU stay, the patient required hemodialysis, red blood cell transfusions, high positive end-expiratory pressure (up to 20 cm H2O), and use of norepinephrine (maximum dose of 0.5 μg/kg/min). He received treatment with meropenem,vancomycin, moxifloxacin, co-trimoxazole and voriconazole due toStreptococcus pneumoniaeandStaphylococcus aureusbacteremia (endocarditis was ruled out); ventilator-associated pneumonia due toS.maltophilia,E. cloacae,andAspergillus fumigatus.Subsequently,liver chemistry showed a cholestatic pattern (R factor < 2) with a persistent increase in ALP and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels.Initial diagnostic workup with abdominal ultrasound was negative.

The patient improved his general condition and was discharged 2 mo after admission. During followup, he presented with jaundice; liver chemistry reported TB 9.47 mg/dL, DB 5.62 mg/dL, and ALP of 1695 U/L. Viral hepatitis panel and autoimmune cholestatic disease-specific antibodies were negative.Magnetic resonance cholangiography was performed, showing multiple areas of short stenosis with a pattern of SSC (Figure 1C). ERCP was performed in which filling defects of the main bile duct were identified in cholangiography; after sphincterotomy, bile sludge and biliary casts were obtained. Despite the ERCP, there was no improvement in liver function test, showing persistent elevation of ALP levels and TB 22.7 mg/dL.

Case 3:During her 20-d ICU stay, the patient required hemodialysis, high positive end-expiratory pressure (up to 20 cm H2O), and use of norepinephrine (maximum dose of 0.13 µg/kg/min). She developed ventilator-associated pneumonia due toPseudomonas aeruginosaand received treatment with imipenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, and moxifloxacin.

During her stay, she presented with progressive cholestasis (R factor of < 2) reaching TB up to 17.32 mg/dL, DB 11.59 mg/dL, GGT 211 U/L, and ALP 705 U/L. Abdominal CT scan showed intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary dilation without evident cause of obstruction. Viral hepatitis panel and autoimmune cholestatic disease-specific antibodies were negative. Magnetic resonance cholangiography was performed, showing intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts with irregular morphology, without evidence of obstruction and periportal edema (Figure 1D).

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

With these findings, including clinical course, ruling out other alternative diagnoses and a close and temporal relationship with SARS-CoV-2 infection, a diagnosis of secondary SSC due to severe COVID-19 was made.

TREATMENT

Case 1:Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid, cholestyramine, and sertraline was started, showing no clinical improvement on liver chemistry at 8 wk, with persistent elevation of ALP, TB, and GGT.

Case 2:Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid was started, showing no clinical improvement on liver chemistry.

Case 3:Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid was started, with persistent elevation of ALP, TB, and GGT.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1:Currently, the patient remains under follow-up without cholestasis improvement and is being evaluated for liver transplantation at our center.

Case 2:A vibration-controlled transient elastography was performed 6 mo after severe COVID-19 admission showing a median of 20.2 KPa (interquartile range/med 17%; FibroScan Echosens™, M probe). Currently, the patient is under palliative care due to Fournier's gangrene and penile necrosis associated sepsis. Liver transplantation protocol was stopped.

Case 3:The clinical evolution of the patient was protracted, and 1 mo after admission, she presented with cardiorespiratory arrest that was not reversible after advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers.

DlSCUSSlON

SCC is a chronic cholestatic disease, derived from multiple insults to the biliary tract including chronic obstruction, infectious disease, autoimmune, and ischemic cholangiopathy. Similar to primary SSC, its manifestations include chronic cholestasis, radiologic evidence of stenosis and dilations of the biliary tract, and the potential to progress to liver cirrhosis.

In 2001, Scheppachet al[3] reported a series of 3 patients admitted to the ICU due to extrahepatic infections without preexisting biliary or hepatic disease. During their stay, all three developed progressive persistent cholestasis with radiologic (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] and ERCP)evidence of biliary dilation and stenosis without mechanical obstruction, and eventually progression to liver cirrhosis. In recent years, many centers worldwide have reported SSC in a growing number of patients who have recovered from critical illnesses.

The key element in the pathophysiology of SCC in critically ill patients (SSC-CIP) seems to be ischemia. Severe hypotension, mechanical ventilation, hypoxemia, red blood cell transfusion, and the use of vasopressors all cause significant hemodynamic changes, which directly damage the epithelium of the intrahepatic biliary tract, whose only source of arterial blood supply comes from the peribiliary vascular plexus, this favors the formation of strictures and biliary casts from necrosis tissue and collagen, which also causes mechanical obstruction. These patients present with persistent cholestasis, 7-9 d after the beginning of the condition that led them to the ICU, followed by hyperbilirubinemia; usually with normal or mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; cholestasis persists even after the critical illness has resolved. Filling defects from biliary casts, stenosis and dilations of the intrahepatic biliary tract can be found in imaging studies (MRI and ERCP).Histopathology is highly unspecific, with only 30% of biopsies showing cholestasis associated morphologic changes with different degrees of liver fibrosis[4].

In 2020 with the emergence of COVID-19, many patients were admitted to the ICU, requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation and use of vasopressors due to shock and severe hypoxemia; which are factors associated with ischemic injury to the biliary tract. Since then, some centers have reported cases of progressive and persistent cholestasis in COVID-19, 16 patients (Table 1) with abnormal findings on MRI or ERCP (beading of intrahepatic ducts, bile duct wall thickening with enhancement,and peribiliary diffusion high signal) some associated with the use of Ketamine[2,5-10]. Rothet al[2]described 3 patients who developed prolonged and severe cholestasis during recovery from severe COVID-19. Clinical, histologic, and imaging features of these 3 patients were similar to those of SSC-CIP with few exceptions; no biliary casts were found during ERCP and biopsies revealed severe cholangiocyte injury and intrahepatic microangiopathy suggesting direct biliary injury from SARS-CoV-2.Only 1 of 3 biopsies was positive for SARS-CoV-2 in immunohistochemistry andin situhybridization.

The 3 cases described here (Table 2), could also represent a confluence between SSC-CIP and direct hepatic injury from COVID-19. Our patients were admitted to the ICU due to severe COVID-19 requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation and vasopressors and developed cholestasis after admission, which was progressive and persisted even after resolution of choledocholithiasis and long after cardiopulmonary recovery. Characteristic imaging changes were found in MRI in our patients such as intrahepatic bile ducts stenosis and histopathologic changes were identical to those reported by Rothet al[2], suggesting a direct biliary injury from SARS-CoV-2. We did not perform immunohistochemistry andin situhybridization for SARS-CoV-2 due to lack of availability in our center.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics

Nevertheless, we must take into consideration that the differential diagnosis of cholestasis in the ICU is broad, and one important diagnosis to consider is DILI. Bile duct injury due to DILI has emerged as a distinct entity, causing persistent cholestasis and cholangiographic changes consistent with SSC. Our patients received antibiotics and ketamine, both associated with bile duct injury due to DILI. However,the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences/Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method Score discarded causality in all cases, mostly because other causes of cholestasis could not be ruled out.

Prognosis in patients with SSC-CIP is poor, with a median transplant-free survival of 13-44 mo;significantly lower than other causes of SSC. Transplant-free survival at 1 year is 55% and 14% at 6 years[4]. In patients with COVID-19 cholangiopathy, prognosis is not well known; to our knowledge, there is one reported case of a 47-year-old man with a successful orthotopic liver transplantation post COVID-19 and is doing well with normal liver tests for 7 mo[9].

CONCLUSlON

We believe that our diagnosis is consistent with post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy, although elements of the clinical course, histopathology and radiologic findings may be shared with SSC-CIP, severe COVID-19 is the common element in these patients, and seems to be associated with unique histopathologic features not previously observed in SSC-CIP. Further investigation into treatment and prognosis is required, mostly because persistent cholestasis may lead to liver cirrhosis. Therefore, we propose that severe COVID-19 infection should be considered a potential risk factor for chronic liver disease and liver transplantation.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Mayorquín-Aguilar JM, Lara-Reyes A, and Revuelta-Rodríguez LA were the patient´s gastroenterology fellows during their hospitalization; Macías-Rodríguez RU and Flores-García NC were the attending hepatologists; Mayorquin-Aguilar JM, Lara-Reyes A, Macías-Rodríguez RU, and Ruiz-Margain A reviewed the literature and contributed to the manuscript drafting; Jiménez-Ferreira MA was the gastrointestinal pathology fellow in charge of the interpretation and handling of the pathology images.

lnformed consent statement:The cases included in this manuscript signed a general informed consent, provided to all patients admitted to our institution with the diagnosis of severe COVID-19. In the manuscript no information regarding ID, name or physical characteristics allowing recognizing the identity of the patients is provided.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Mexico

ORClD number:Juan M Mayorquín-Aguilar 0000-0002-5805-1455; Aldo Lara-Reyes 0000-0002-0564-0299; Luis Alberto Revuelta-Rodríguez 000-0003-1302-7678; Nayelli C Flores-García 0000-0003-3930-2682; Astrid Ruiz-Margáin 0000-0003-2779-8641; Marco Antonio Jiménez-Ferreira 0000-0001-7160-1418; Ricardo Ulises Macías-Rodríguez 0000-0002-7637-4477.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:European Association for the Study of the Liver; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Asociacion Mexicana de Hepatologia; Asociacion Mexicana de Endoscopia Gastrointestinal; Asociacion Mexicana de Gastroenterologia.

S-Editor:Yan JP

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Yan JP

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Long-term liver allograft fibrosis: A review with emphasis on idiopathic post-transplant hepatitis and chronic antibody mediated rejection

- Outcomes of patients with post-hepatectomy hypophosphatemia: A narrative review

- Simple diagnostic algorithm identifying at-risk nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients needing specialty referral within the United States

- Higher cardiovascular risk scores and liver fibrosis risk estimated by biomarkers in patients with metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

- Prevalence of sarcopenia using different methods in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease is associated with low muscle mass and strength in patients with chronic hepatitis B