Higher cardiovascular risk scores and liver fibrosis risk estimated by biomarkers in patients with metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

2022-09-01GiovanniAlejandroSalgadoAlvarezSamantaMayaninPintoGalvezUrielGarciaMoraAnaDelfinaCanoContrerasCristinaDurRosasBryanAdriPriegoParraArturoTrianaRomeroMercedesAmievaBalmoriFedericoRoeschDietlenSophiaEugeniaMartinezVazquezIn

Giovanni Alejandro Salgado Alvarez, Samanta Mayanin Pinto Galvez, Uriel Garcia Mora, Ana Delfina Cano Contreras, Cristina Durán Rosas, Bryan Adrián Priego-Parra, Arturo Triana Romero, Mercedes Amieva Balmori, Federico Roesch Dietlen, Sophia Eugenia Martinez Vazquez, Ines Osvely Mendez Guerrero, Luis Alberto Chi-Cervera, Raúl Bernal Reyes, Leonardo Alberto Martinez Roriguez, Maria Eugenia Icaza Chavez,Jose Maria Remes Troche

Giovanni Alejandro Salgado Alvarez, Samanta Mayanin Pinto Galvez, Uriel Garcia Mora, Ana Delfina Cano Contreras, Cristina Durán Rosas, Bryan Adrián Priego-Parra, Arturo Triana Romero,Mercedes Amieva Balmori, Federico Roesch Dietlen, Jose Maria Remes Troche, Instituto de Investigaciones Médico-biologicas, Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz 91700, Veracruz,Mexico

Sophia Eugenia Martinez Vazquez, lnes Osvely Mendez Guerrero, Department of Gastroenterología, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México 14080, México, Mexico

Luis Alberto Chi-Cervera, Clínica de Especialidades Gastrointestinales y Hepáticas, Hospital Star Medica, Merida 97133, Yucatan, Mexico

Raúl Bernal Reyes, Department of Gastroenterologia, Sociedad Española de Beneficencia,Pachuca 42000, Hidalgo, Mexico

Leonardo Alberto Martinez Roriguez, Department of Gastroenterologia, Clínica de Rehabilitación Metabólica Digestiva y Hepática, Mexico 14080, Mexico, Mexico

Maria Eugenia lcaza Chavez, Department of Gastroenterologia, Hospital Star Médica de Mérida,Merida 97133, Yucatan, Mexico

Abstract BACKGROUND The definition of metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)allows identification of metabolically complicated patients. Fibrosis risk scores are related to cardiovascular risk (CVR) scores and could be useful for the identification of patients at risk of systemic complications.AIM To evaluate the relationship between MAFLD and CVR using the Framingham risk score in a group of Mexican patients.METHODS Cross-sectional, observational and descriptive study carried out in a cohort of 585 volunteers in the state of Veracruz with MAFLD criteria. The risk of liver fibrosis was calculated with aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease score and fibrosis-4, as well as with transient hepatic elastography with Fibroscan®. The CVR was determined by the Framingham system.RESULTS One hundred and twenty-five participants (21.4%) with MAFLD criteria were evaluated, average age 54.4 years, 63.2% were women, body mass index 32.3 kg/m2. The Framingham CVR was high in 43 patients (33.9%). Transient elastography was performed in 55.2% of volunteers; 39.1% with high CVR and predominance in advanced fibrosis (F3-F4). The logistic regression analysis showed that liver fibrosis, diabetes and hypertension independently increased CVR.CONCLUSION One of every three patients with MAFLD had a high CVR, and in those with high fibrosis risk, the CVR risk was even greater.

Key Words: Fatty liver; Cardiovascular risk; Hepatic steatosis; Fibrosis; Liver disease

lNTRODUCTlON

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by steatosis > 5% in the absence of alcohol consumption and other causes of liver disease[1]. Due to its close relationship with the components of the metabolic syndrome, a consensus of international experts proposed a change of name, resulting in the concept of metabolicdysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) as the new terminology[2-4].

The presence of diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity and metabolic dysregulation to establish the diagnosis of MAFLD can help identify patients with metabolically complicated fatty liver disease and consequently with higher cardiovascular risk(CVR). We consider that the Framingham score can be a useful tool in the evaluation of CVR in patients with MAFLD because it independently assesses the presence of diabetes as a CVR factor[5,6].

The Hepatic Fibrosis Scoring System is related to CVR scores in patients with MAFLD and can be useful for identifying the risk of systemic complications[7]. However, we do not have Mexican cohorts that consider the new definition of MAFLD and CVR[8]. Therefore, the objective of our work was to evaluate the relationship between MAFLD and CVR in a group of Mexican volunteers using the Framingham scale.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional, observational and descriptive study carried out in the population of a crosssectional sample evaluated at the Instituto de Investigaciones Medico Biologicas and Centro de Servicios en Salud of the Universidad Veracruzana during February to March 2020. Residents of the State of Veracruz aged > 18 years were invited to participate. After signed informed consent, a medical evaluation was performed, which consisted of anthropometry measurements [weight, height, body mass index (BMI), waist and hip circumference, waist-hip index], biochemical studies [hematic biometry, glucose, creatinine, uric acid, lipids, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase (AP), bilirubin, albumin and insulin] and liver ultrasound. In addition,blood pressure, personal history of DM, systemic arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular events, and tobacco use were recorded.

From the studied population, patients older than 40 years with diagnostic criteria for MAFLD were included. Patients with cancer, terminal disease, history of cardiovascular events and pregnant women were excluded.

The risk of liver fibrosis was determined with aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index(APRI), NAFLD and fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores. The APRI was at high risk of significant fibrosis with a score of > 1.5, indeterminate 0.5-1.5, and unlikely or absent < 0.5; NAFLD score was considered high risk with > 0.675, indeterminate 1.455 to 0.675, and absent < 1.455; FIB-4 score was considered high risk with > 3.25, indeterminate 1.45-3.25 and absent < 1.45[9-11]. Transient elastography (TE) with Fibroscan®was performed in patients with undetermined and high risk of liver fibrosis[12,13]. The CVR was calculated with the Framingham system which evaluates: age, sex, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure, use of antihypertensive drugs, tobacco consumption, DM,history of vascular disease; classifying patients as low, moderate or high CVR[14,15].

The project was carried out in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practices and prior approval of the Ethics Committee with number IIMB-UV 2020/03.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of the results, elaboration of figures and tables was carried out with the IBM SPSS®Statistics version 22.0 . Nominal and ordinal variables were described with frequencies and percentages,continuous and discrete variables with measures of central tendency and dispersion according to their distribution. The comparison between groups was carried out with theχ2test and analysis of variance.Nonparametric statistics with Spearman’s correlation test were used in the relationship between CVR and fibrosis. Statistical significance was considered when thePvalue was < 0.05.

RESULTS

Population characteristics

Of the 585 volunteers, 125 (21.4%) who met the inclusion criteria were studied, 79 (63.2%) were women,average age 54.4 ± 8.8 years, BMI 32.3 ± 5.3 kg/m2.

CVR assessment

According to the Framingham score, 46 patients (36.2%) had mild CVR, 36 (28.3%) moderate and 43(33.9%) high. No differences were found by sex or BMI between the CVR categories. The patients’ age with high CVR was 59 ± 8.4 years; higher than in mild and moderate CVR (P= 0.028). The presence of DM, hypertension and tobacco use was significantly higher in patients with high CVR. The concentration of glucose and insulin was higher in patients with high CVR; therefore, the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) index showed a value > 3.0 compatible with insulin resistance (P= 0.000) compared to patients with low and moderate CVR (HOMA-IR 1.96-3). The rest of the biochemical parameters evaluated did not show significant differences (Table 1). Fibrosis scores showed an increasing trend in patients with high CVR; however, this difference was not significant(0.094).

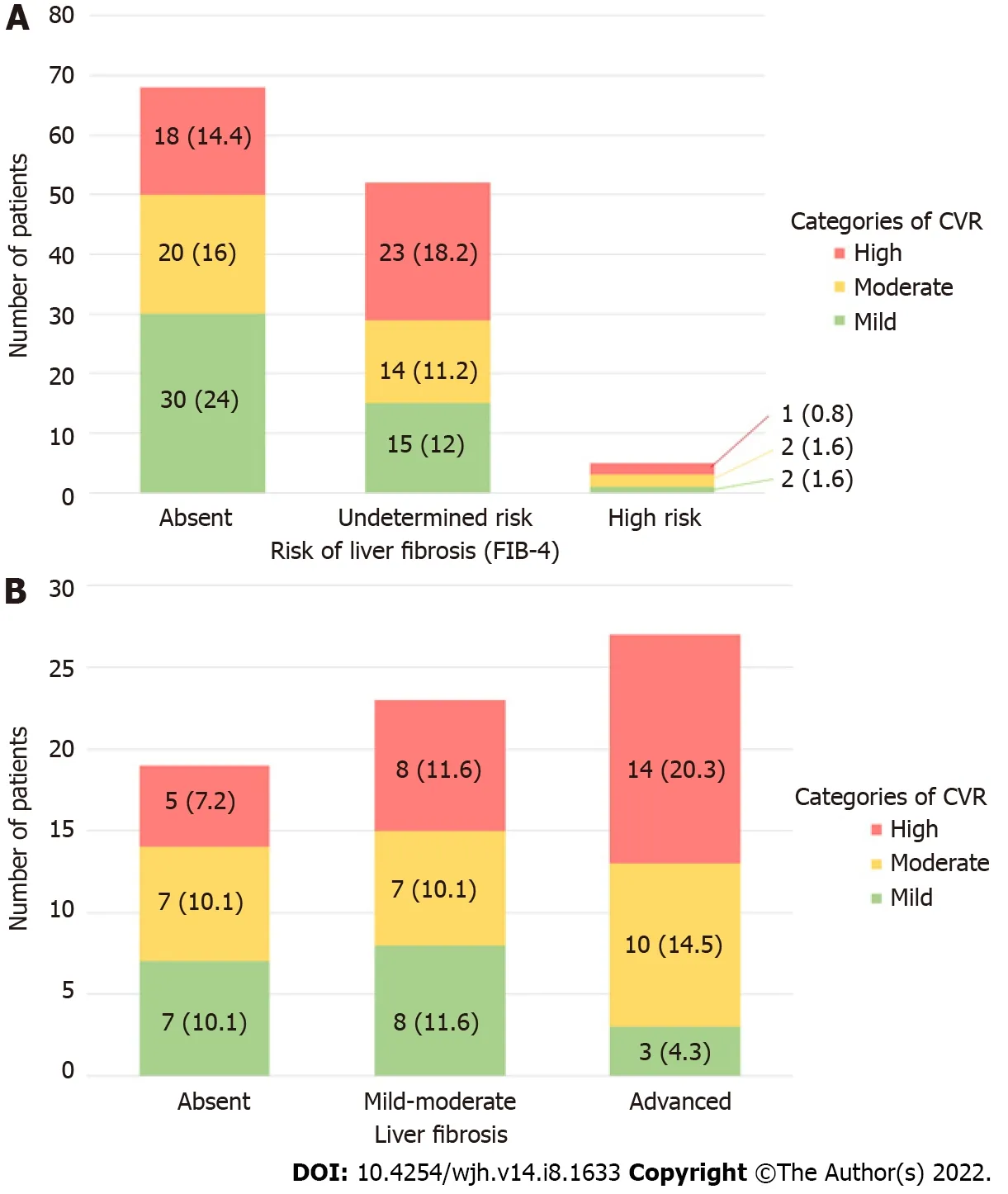

Table 1 Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients with metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk estimated by the Framingham system (n = 125)

Evaluation of liver fibrosis

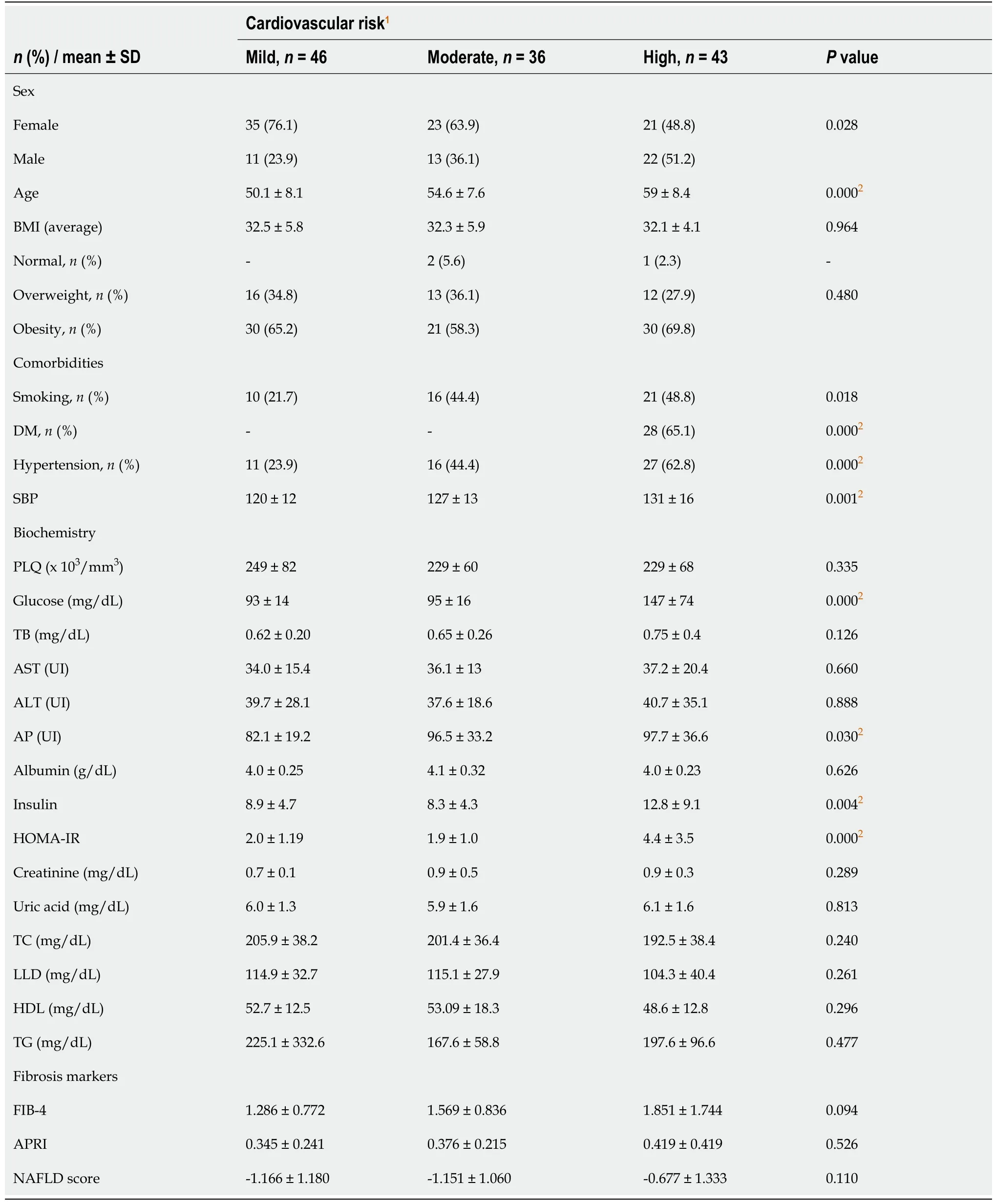

The distribution between the fibrosis risk stages by FIB-4, NAFLD and APRI scores is shown in Figure 1.Fifty-two patients (44.8%) with indeterminate and high risk of fibrosis were identified according to FIB-4, 79 (62.2%) according to NAFLD score and 21 (15.6%) with APRI.

Figure 1 Frequency of liver fibrosis risk in patients with metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease according to fibrosis-4,nonalcoholic fatty liver disease score and aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, n (%). APRI: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4.

The study was performed in 69 patients (55.2%) with indeterminate or high risk of fibrosis. Patients were identified as follows, F0: 19 (27.5%), F1: 12 (17.4%), F2: 11 (15.9%), F3: 13 (18.8%) and F4: 14 (20.3%).In the evaluation of hepatic steatosis by controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) the results were the following, S0: 13 patients (18.8%), S1: 7 (5.5%), S2: 3 (2.4%) and S3: 46 (36.2%).

The age distribution showed a significant difference between the risk of fibrosis due to FIB-4, as it was higher in the group with indeterminate fibrosis and lower in patients with absence of fibrosis (P=0.000). The BMI and the comorbidities evaluated did not show significant differences between the risk groups. Patients with high risk of fibrosis had decreased platelet and albumin counts, as well as significantly elevated levels of total bilirubin, AST, and phase angle compared to patients without fibrosis or indeterminate risk of fibrosis (P= 0.000).

Liver fibrosis and CVR

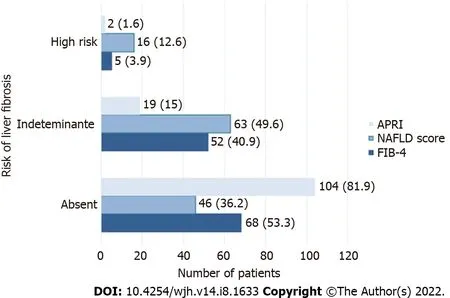

The correlation of liver fibrosis risk by FIB-4 and CVR according to the Framingham system showed that 33.4% of patients with MAFLD had a high CVR, predominantly in patients with indeterminate risk of fibrosis (18.2%). 14.4% of the patients with no fibrosis had a high CVRversus19.8% of the patients with an indeterminate or high risk of fibrosis. The risk of fibrosis did not show a significant correlation with the severity of CVR (P= 0.257). The categories of CVR and risk of fibrosis by FIB-4 can be observed in Figure 2A.

Figure 2 Distribution of cardiovascular risk. A: Distribution of cardiovascular risk (CVR) according to the Framingham system in patients with metabolicdysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and risk of liver fibrosis according to fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) (n = 125); B: Distribution of CVR estimated by the Framingham system in patients with metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease according to hepatic fibrosis estimation with transient elastography (n = 69), n (%).Degrees of fibrosis by Kpa according to METAVIR: Absent: F0; Mild-moderate: F1 and F2; Advanced: F3 and F4. CVR: Cardiovascular risk; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4.

In 69 patients evaluated with TE, 18 patients (26.1%) had mild CVR according to the Framingham system, 24 (34.7%) with moderate and 27 (39.1%) with high risk. It was observed that the group with the greatest number of patients with high CVR were those with advanced fibrosis. 39.1% of patients with MAFLD had a high CVR at the time of diagnosis with a predominance of advanced fibrosis (F3-F4). In relation to fibrosis severity, it was noted that in advanced fibrosis, 34.8% had moderate to high CVR,predominantly observing the correlation between advanced fibrosis and high CVR. A statistically significant relationship was reported between the presence of fibrosis and the severity of CVR (P=0.026). The distribution of the different risk categories in patients with absent or mild-moderate fibrosis was heterogeneous as shown in Figure 2B.

Hepatic steatosis and CVR

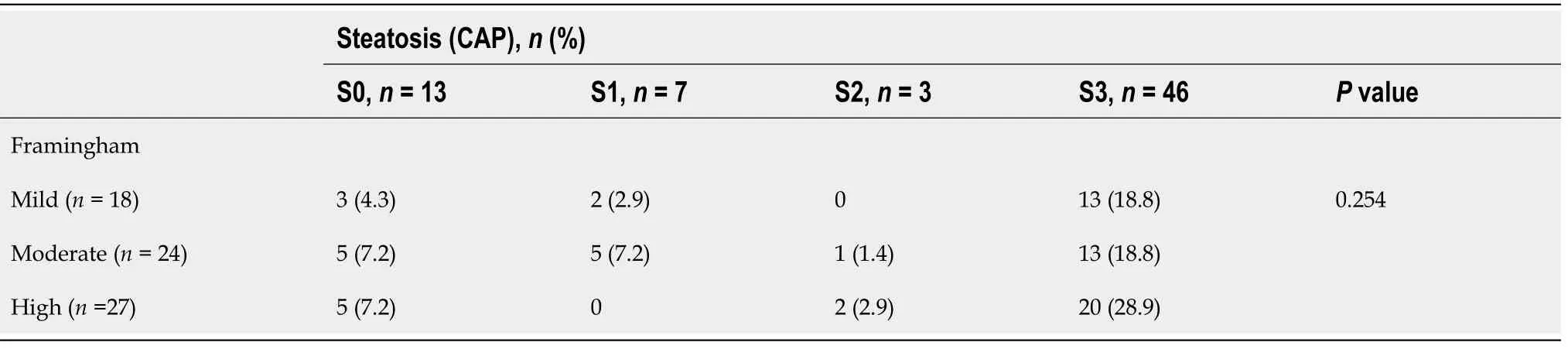

The correlation between CAP and CVR showed that 28.9% of the patients with S3 had a high CVR.Although most of our patients were found in S3, the severity of the CAP did not show a significant relationship with the severity of the CVR (P= 0.254). Table 2 shows the correlation between CVR and CAP. In logistic regression analysis, the presence of fibrosisP= 0.007 [95% confidence interval (CI):0.157-35.376], DMP= 0.000 (95%CI: 0.791-43.555) and hypertensionP= 0.035 (95%CI: 0.085-5.228) were independently and significantly associated with the CVR, but not with the presence of steatosisP=0.220 (95%CI: 0.144-22.921).

Table 2 Correlation between hepatic steatosis and cardiovascular risk by the Framingham system (n = 69)

DlSCUSSlON

MAFLD is currently the most common chronic liver disease worldwide, present in 25% to 30% of the population. Although the severity of the disease criteria has not been established, it is described that thepresence of fibrosis is the most important prognostic marker of mortality, independent of the severity of the fatty infiltration[16,17]. Our study, carried out in a Mexican population, showed that one out of every three patients with MAFLD had a high CVR, and the higher the fibrosis the greater the CVR. We show novel results as it is one of the first studies to use the new definition of MAFLD in association with CVR[18].

The change in diagnostic criteria from NAFLD to MAFLD was made recently. Therefore, in Mexico we have few prevalence studies with the new definition. The study carried out by Bellentaniet al[19] in 585 healthy volunteers published as a summary showed a prevalence of MAFLD of 42.1; high if we compare it with the prevalence of NAFLD estimated worldwide. In our cohort, we found that 21.4% of the population over 40 years of age had MAFLD, like the prevalence of NAFLD reported in the adult population of various western countries. Although the prevalence of DM in patients with NAFLD is 50% to 70%, in our population, it was lower (22.4%). We found a high prevalence of overweight and obesity (97.6%), like that observed in other populations where between 80% and 90% has been reported.We consider that the differences may be because previously conducted studies consider the NAFLD criteria[20,21].

Liver biopsy is the gold standard in the evaluation of fibrosis, but it carries the risk of complications coupled with high cost. For this reason, the use of noninvasive systems such as serum markers, TE or magnetic resonance imaging is recommended. TE with FibroScan®is the most widely used and validated elastography worldwide with good sensitivity and specificity to diagnose F4 stage (both 92%).The FIB-4 index has been shown to be superior to other noninvasive markers in the identification of advanced fibrosis in patients with MAFLD; therefore, it is the marker of choice in the two-step algorithms[22]. Shahet al[23] compared the diagnostic performance of noninvasive fibrosis markers and concluded that the FIB-4 index is better at identifying advanced fibrosis in patients with MAFLD. The diagnostic performance of the markers used in our study showed similar results, with a higher correlation of advanced fibrosis by FIB-4 with TE.

The main cause of death in patients with MAFLD is cardiovascular disease, and the secondary causes are related to the liver. Cardiovascular diseases most frequently observed in patients with MAFLD are left ventricular dysfunction, atherosclerotic disease, disturbances in the cardiac conduction system, and cerebral ischemic events. These observations establish the close relationship between the severity of liver disease and the risk of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events[24]. Despite current evidence, in daily clinical practice, MAFLD is considered a benign entity. For this reason, our study focused on the identification of patients with MAFLD and a high risk of cardiovascular events and its relationship with hepatic fibrosis markers. Our purpose was to recommend early identification mechanisms to prevent complications and decrease mortality.

Fatty liver is associated with increased CVR regardless of the presence of DM, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Therefore, early identification is important to reduce cardiovascular mortality[25]. Our results show that the majority of the population with MAFLD has mild CVR according to the Framingham system. However, more patients with higher CVR were identified at indeterminate risk of fibrosis due to FIB-4 (18.2%). Our results showed that most of the patients with high CVR have advanced fibrosis (F3-F4). In addition to this, these patients had a higher frequency of DM and hypertension. These results reflect that the higher the CVR, the greater the risk of liver fibrosis, which allows the early identification of patients with compensated advanced liver disease.

Cardiovascular disease and arteriosclerosis are the result of endothelial damage, dyslipidemia, and oxidative stress reported more frequently in patients with MAFLD. However, as reported in the literature, the severity of hepatic fatty infiltration did not demonstrate a relationship with CVR[5,26].

Various studies have reported that the FIB-4 index ≥ 2.67 is independently associated with coronary atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events; therefore, with an increase in CVR[27,28]. In our study,results similar to those published in previous clinical trials were observed, exhibiting a correlation between FIB-4 and the CVR systems compared to NAFLD and APRI (P< 0.05). Another limitation was that it was not a nationally representative population, as it only included volunteers from the State of Veracruz.

It is important to mention and recognize that our study had limitations that must be considered. One of them was that the prevalence of MAFLD was calculated in volunteers older than 40 years and in different clinical trials the population older than 18 years was included; therefore, the prevalence could be underestimated in our cohort. Finally, it is recognized that the gold standard for evaluating fibrosis and steatosis in patients with MAFLD is liver biopsy. However, due to the risks of this procedure, we performed the evaluation of fibrosis and steatosis with only biochemical markers and transient elastography.

CONCLUSlON

One of every three patients with MAFLD had a high CVR and the greater severity of fibrosis correlated with a greater CVR. According to our results, the early identification of CVR in patients with MAFLD will allow establishment of preventive actions and timely treatment to reduce the risk of mortality in this population.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

The investigation was carried out in an open population without a diagnosis of metabolic-dysfunctionassociated fatty liver disease (MAFLD).

Research motivation

To identify patients with MAFLD and establish their cardiovascular risk (CVR).

Research objectives

The objective is to evaluate the relationship between fibrosis and steatosis measured by transition elastography in patients with MAFLD and CVR scores in Mexican patients.

Research methods

Identification of patients with MAFLD in the open population. Subsequently, determination of the risk of fibrosis by noninvasive methods. Finally, CVR was determined by the Framingham risk scale and was related to the presence of fibrosis and steatosis.

Research results

21.4% of the study population met MAFLD criteria. The severity of CVR was related to the presence of fibrosis, but not with the severity of steatosis.

Research conclusions

Patients with MAFLD and liver fibrosis have a higher CVR compared to patients without fibrosis,regardless of the severity of steatosis.

Research perspectives

Prospective research is required to determine the best CVR score in patients with MAFLD.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Salgado Alvarez GA, Pinto Galvez SM, Garcia Mora U and Cano Contreras AD contributed to the first writing of the manuscript, methodology, analysis of results; Durán Rosas C, Priego-Parra BA and Triana Romero A contributed to review and editing; Amieva Balmori M, Roesch Dietlen F, Martinez Vazquez SE and Mendez Guerrero IO contributed to the conception and development of research; Chi-Cervera LA, Bernal Reyes R,Martinez Roriguez LA, Icaza Chavez ME and Remes Troche JM contributed to the conception and development of research, project management, review and editing.

Supported byAsociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología, No. 2020-001.

lnstitutional review board statement:The study was reviewed and approved by the Instituto de Investigaciones Medico-biologicas de la Universidad Veracruzana Institutional Review Board CE-IIMB-2021-01.

lnformed consent statement:Patients signed and provided the informed consent to this study.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:No additional data are available.

STROBE statement:The authors have read the STROBE Statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Mexico

ORClD number:Giovanni Alejandro Salgado Alvarez 0000-0002-3417-2615; Uriel Garcia Mora 0000-0001-5552-4993; Ana Delfina Cano Contreras 0000-0003-4849-8007; Cristina Durán Rosas 0000-0001-6912-9871; Bryan Adrián Priego-Parra 0000-0003-1506-806X; Arturo Triana Romero 0000-0002-9088-0421; Mercedes Amieva Balmori 0000-0002-8734-2593; Sophia Eugenia Martinez Vazquez 0000-0001-5156-9932; Ines Osvely Mendez Guerrero 0000-0002-9308-9352; Luis Alberto Chi-Cervera 0000-0002-3335-8178; Jose Maria Remes Troche 0000-0001-8478-9659.

S-Editor:Ma YJ

L-Editor:Kerr C

P-Editor:Ma YJ

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Long-term liver allograft fibrosis: A review with emphasis on idiopathic post-transplant hepatitis and chronic antibody mediated rejection

- Outcomes of patients with post-hepatectomy hypophosphatemia: A narrative review

- Simple diagnostic algorithm identifying at-risk nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients needing specialty referral within the United States

- Prevalence of sarcopenia using different methods in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease is associated with low muscle mass and strength in patients with chronic hepatitis B

- Effect of probiotics on hemodynamic changes and complications associated with cirrhosis: A pilot randomized controlled trial