A Brief Analysis of Competitive Sports Depicted on the Portrait Bricks and Stones of the Han Dynasty

2022-08-24LiJiaxinLeiLingLiLinandWangDaiqian

Li Jiaxin, Lei Ling, Li Lin, and Wang Daiqian

Sichuan Museum

Abstract: The emergence of competitive sports in ancient China is closely related to military activities. With the evolution and development of society, many sporting events have been introduced to and accepted by, the people and later carried forward from generation to generation. In the Han Dynasty, thanks to the strong national strength and booming economy, competitive sports witnessed rapid development. People at that time, from imperial officials to common people, were all keen on various competitive sports and such sports were also very popular among the folk. Along with this, there emerged multiple monographs on sports. Portrait bricks are the remnants of the lavish burial rituals of the Han Dynasty. As the economy grew and social wealth amassed, the lavish burial custom prevailing since the Spring and Autumn Period reached its peak in the Han Dynasty, especially in the Eastern Han Dynasty. People would bury in tombs along with various articles they used before they died. They would also paint the life of the tomb owner on bricks to decorate the tomb by embedding them in the tomb chamber. The images on the portrait bricks unearthed from the tombs of the Han Dynasty are the most intuitive and convincing physical evidence to reflect the development of competitive sports at that time. We conduct a preliminary study on competitive sports in the Han Dynasty by using the portrait bricks of the Han Dynasty unearthed in Sichuan province and the Yellow River basin as examples, aiming to do our bit to build a sporting powerhouse and a healthy China.

Keywords: portrait bricks of the Han Dynasty, competitive sports, types, development and evolution

Competitive sports refer to competition-oriented sports that are carried out by following certain rules. Most of the sports in early ancient China were related to military activities. In the era of cold weapons, the fight between people and those between people and animals formed the rudiment of some ancient sports. With the evolution and development of history, some events were gradually introduced to the folk from the army and were accepted by common people. These sports were later passed down from generation to generation. In addition, some sports, originally created among the folk, were gradually absorbed and improved by the army and became an indispensable means and approach to military training.

The sports games in ancient China with unique ethnicity come in various forms and types, mainly including: (a) Ball sports:Cuju(a ball game in ancient China, similar to today’s football),Maqiu(a horseback ball game, similar to today’s polo),Chuiwan(a ball game played with a cue, similar to today’s golf), etc; (b) Martial arts:Quanbo(similar to today’s boxing, includingJuediandQuanshu), archery, and martial arts with weapons; (c) Ancient athletics: running, jumping, leaping, and throwing; (d) Healthcare sports; (e) Water sports and ice sports; (f) Board games; and (g) Acrobatics.

These sports collectively represented the entertainment activities of ancient Chinese of different classes, including sports aiming to achieve self-cultivation by the literati and officialdom, competitive games among the common people, and various physical sports from the court to the folk. They were the treasures co-created by all Chinese ethnic groups and reflected the multi-ethnic characteristics represented by the farming culture in the Central Plains, nomadic culture in the grassland, and waterrelated culture in south China.

There was little and fragmented literature about sports games in the Han Dynasty, making it difficult to get the whole picture of Han sports. The most convincing physical evidence is the cultural relics such as portrait bricks and stones unearthed from the tombs of the Han Dynasty. Among these cultural relics, nothing is more intuitive than the images of sports activities on the bricks and stones of the Han Dynasty. According to these images and related literature, we classify sports games in this period into two types: one for physical fitness and the other for self-cultivation and entertainment. Based on the collections in the Sichuan Museum in combination with portrait bricks and stones unearthed from other regions, we probe into the emergence and development of some sports games in ancient times and examine their influence on modern sports culture.

Sports for Physical Fitness

Competitive sports for physical fitness originated from the life, work and battles of humans, including unarmed sports and armed ones. In the long era of cold weapons, people regarded martial arts and physical exercises as the basis for fighting and resisting enemies. The combination of military competition and sports created a wide variety of competitive events, which are widely spread today.

Shoubo (Unarmed Combat)

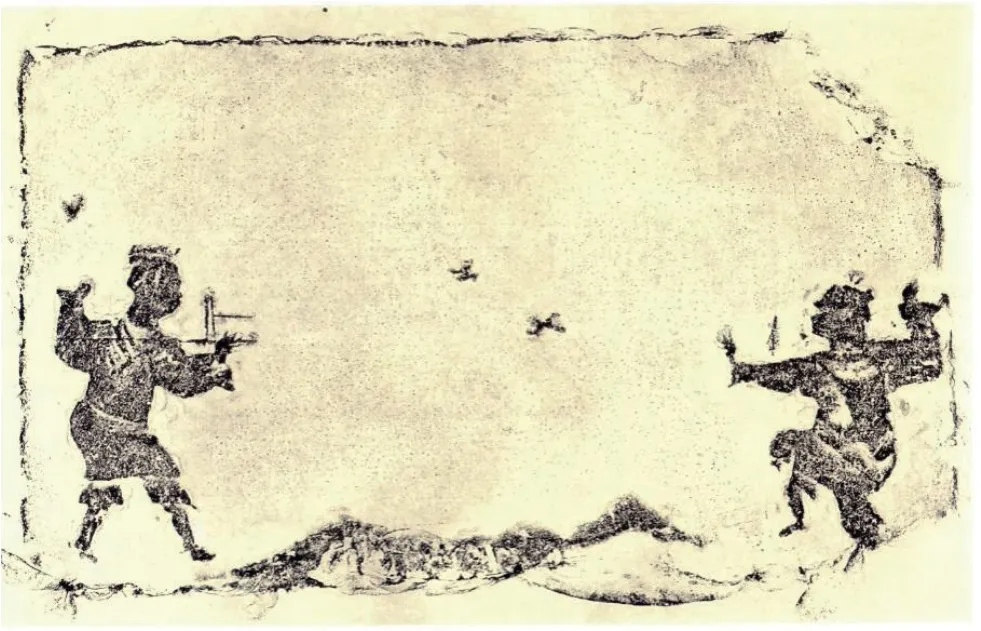

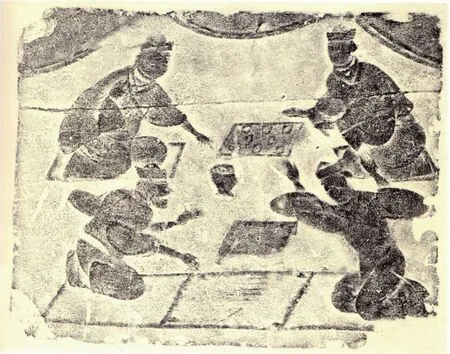

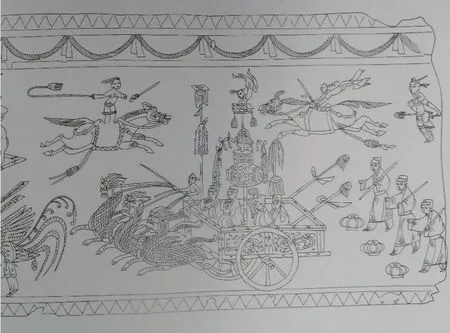

The appearance ofShoubowas originally related toJuediorJueli, a kind of wrestling activity in ancient China. According to theRecords of Strange Tales (Volume I), about 4,600 years ago, a war broke out between the tribe of the Yellow Emperor and that of Chiyou inZhuolu(present-day Zhuozhou in Hebei Province). It is said that the people of Chiyou wore horns on their heads. When fighting, they used their horns to attack, and no one could hold them back. Later in theZhuoluarea, “Chiyou Game” became popular among common people. When playing this game, people would wear bull horns on their heads and use such horns to press against others for fun. This game is also calledJuedi, the oldest form of combat in China. It is directly related to other forms of combat that later appeared such asShoubo,Quanshu(boxing),Xiangpu(sumo) andShuaijiao(wrestling). In the Xia, Shang and Zhou Dynasties, most rulers attached great importance toShouboand were adept at it. As depicted in theRecords of the Grand Historian(1986, p. 16), “King Jie of Xia and King Zhou of Yin could fight jackals with bare hands and chase carriages drawn by four horses with bare feet.” According to theRites of Zhou(1983, p. 82), there was an official role calledHuanrenwhose responsibilities are “launching attacks against enemies; searching for hidden traitors in the army; foiling enemies’ plans for aggression; patrolling the kingdom; catching spies; reasoning with enemies; demonstrating military prowess; and receiving surrenders.” Capturing criminals and fighting enemies with bare hands are necessary skills for officials likeHuanren. During the Warring States Period, more frequent wars contributed to the rapid development and improvement of the technique ofShoubo. Right under this circumstance, theoretical knowledge about this technique was formed. InZhuangzi(1986, p. 23), it reads, “skillful wrestlers begin with open trials of strength, but always end with masked attempts (to gain the victory); as their excitement grows excessive, they display much wonderful dexterity.” This sentence depicted the essence ofShoubotechnique, that is, attacking covertly and after the rival has attacked to make better use of the situation to win, which is vital inShoubocompetition. In the Han Dynasty, despite the improvement of weapon production techniques and the combination of the infantry and cavalry in the battle,Shoubowas still an important skill for officers and soldiers. In theBook of Han: Biography of Li Guang(1964, p. 2456), it is recorded that Li Ling, the grandson of Li Guang, a famous General in the Western Han Dynasty, once led 5,000 infantry soldiers on an expedition to conquer the frontiers of the Han Dynasty. After a few days of fierce fighting with the cavalry of Huns (a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples), he “ran out of arrows after a long march for fighting.” Finally, “he and his soldiers had to fight the enemies who carried sharp swords with bare hands, and moved northwards to fight against the enemies with all their efforts for survival.” This demonstrated thatShoubowas the last resort to survive in a brutal war. During this period,Shouboalso became a way of cultural entertainment for the ruling class. According to theBook of Han: Records of Emperor Ai of Han(1964, p. 345), Emperor Ai of Han was keen on “watchingShoubogames, and shows little interest in court music.” In theBook of Han: Biography of Gan Yanshou(1962, p. 3007), it reads, “Gan Yanshou participated in the combating test and won a high score, so he was promoted asQimenlang(an official position in Han Dynasty). He was then favored by the emperor due to his talents and bravery.” Here, “Bianis also calledShoubo.” It shows thatShoubogradually transformed from military training to entertainment games in the Han Dynasty. We can see from the unearthed portrait bricks and stones thatShouboin the Han Dynasty is similar to Sanda (or free combat) in modern martial arts, which uses such techniques as kicking, beating, wrestling, and holding during the combat. The portrait brick of “Chasing the Skylarks” collected in the Agency of Cultural Relics in Xindu District, Chengdu, Sichuan province (see figure 1) reflects the training scene ofShouboin the Han Dynasty. In the picture, two people, wearing short clothes and headscarves, confront each other with their bare hands. The person on the left poises in a high empty stance, and clenches his two hands into fists, one front and one back, ready to combat with his rival.

Figure 1. The portrait brick of “Chasing the Skylarks” in the Eastern Han Dynasty collected in the Agency of Cultural Relics in Xindu District, Chengdu, Sichuan province

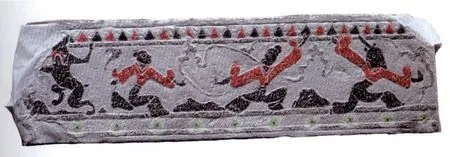

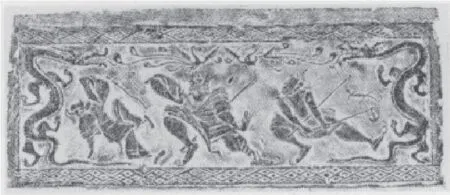

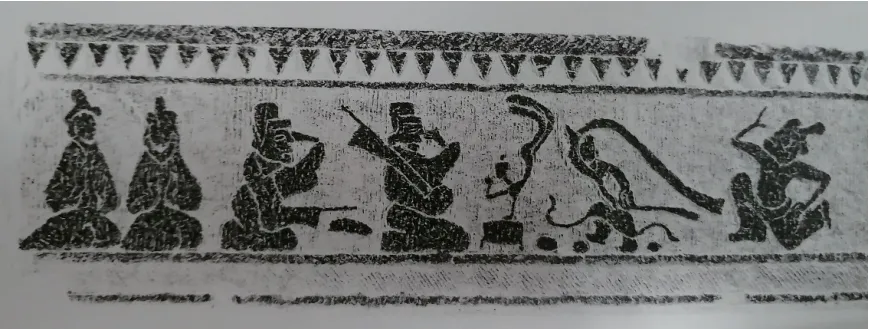

The person on the right makes a lunge and clenches his two hands into fists, one in the horizontal direction and the other rising high. He looks ahead and is ready to accept the challenge. Between them are several frightened skylarks. The picture vividly captures the critical moment ofShoubowhen the two rivals are about to showcase their strengths. Since this picture clearly shows the beginning of a combat, some scholars think that the title of the picture does not match its content at all (Liu & Zhao, 2018, p. 122). We completely agree with this view. In a stone tomb of the Han Dynasty in Chenpeng village, Nanyang city, Henan province, there was a portrait stone embedded right in the northern front door lintel dubbed “Warriors & the Bear” (see figure 2). In the picture, three people, all wearing short warrior costumes, are combating with their bare hands. Each move, attacking or defending, displays the skills of the combatants, which is similar toShoubo. This indicates thatShoubois the initial form of boxing. A portrait brick of “Shoubo” unearthed in Qiying village, Dengzhou city, Henan province (see figure 3) shows a wonderful scene of combat where a warrior in armor with a sword in hand, is making a lunge and fighting two men with bare hands. The man on the left has fallen flat on his back, with his shoes and sword falling on the ground. The man on the right with a sword at his waist is wielding his tomahawk with both hands to attack the warrior. The whole scene is imbued with roughness and boldness, with a strong visual impact. These images show that all combatants are powerful and agile men in short clothes. There are few differences betweenShouboandJuedi(wrestling) in the Han Dynasty. Both games evolved from military training and then became recreational games. Therefore, it is hard to distinguish one from the other from either historical materials or images.

Figure 2. Portrait stone of “Warriors & the Bear” embedded right in the northern front door lintel of a tomb in the Han Dynasty and unearthed in Chenpeng village, Nanyang, Henan province

Figure 3. Portrait brick of “Shoubo” unearthed in Qiying village, Dengzhou, Henan province

The history ofShoubocan be traced back to primitive society whenShoubowas first calledHudi. Later, it was calledJuedi,Xiangpu,Xiangbo,Jueli,Guanjiao,Zhengjiao,Liaojiao,Shuaijiao, etc. However, all these names were discarded and replaced byShuaijiao(wrestling). Today, wrestling is widely regarded as one of the oldest competitive sports in the world.

Wushu (Martial Art)

In theVolume of Sports of Dacihai(2008, p.320), the term Wushu is explained as follows: “Wushu, also known as ‘Wuyi’ or ‘Kung Fu,’ was formerly called ‘Guoshu’ and is a traditional Chinese sports event.” InShiben(orBook of Origins) (1957, p. 11), it says, “In the southern Ba County, there were five tribes…They had no ruler and all worshiped ghosts and gods. They agreed that the man who is able to stab a sword into rock will be their ruler” (Gao, 2009, p. 459). This record may be regarded as the beginning of Wushu competitions. InThe Book of Zhou Change,it says “Alternation betweenyinandyangis called the way…Therefore inThe Zhou Book of Change, there is the supreme ultimate at first. The supreme ultimate gives birth to the two primary forms (yinandyang), the two primary forms give birth to the four basic images (greateryin, greateryang, lesseryin, and lesseryang), and the four basic images to the eight trigrams. Changes of the eight trigrams can determine good fortune or disaster. Determination of good fortune and disaster can help people accomplish great causes” (2009, p. 459). Wushu was first seen performed for recreational purposes and endowed with rich connotation in Han Dynasty. This can be testified by the literature, and portrait bricks and stones of the Han Dynasty. In addition toShouboand Quanshu mentioned above, the sword dance was also very popular in the Han Dynasty. According to theRecords of the Grand Historian: Annals of Xiang Yu, Xiang Zhuang and Xiang Bo once performed sword dance at Hongmen Banquet. Xiang Zhuang said, “Please allow me to perform a sword dance since there is no other form of entertainment in the army.” This shows that sword dance was a form of entertainment at that time, and was the initial display of swordsmanship in Wushu.

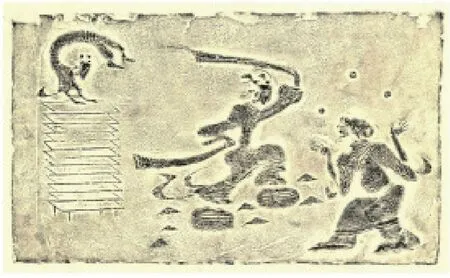

The portrait brick of “Sword Dance at a Banquet” collected in the Sichuan Museum (see figure 4) shows the sword dance as a form of entertainment. On the upper right of the picture, a shirtless man performs by carrying a club with his left elbow while holding a sword in his right hand. He, together with the “ball performer,” dancer and drum accompanist in the picture added fun to the banquet. In the Han Dynasty, it was trendy to wear a sword or perform fencing. With more and more importance attached to close-quarters combat and weapon use, Wushu changed from military training to a sports event. At that time, there emerged a group of swordsmen who were proficient in swordsmanship and relied on the rich for supplies. They paid attention to the inheritance and techniques of swordsmanship. As schools of different genres were established, specialized swordsmen of different schools began to teach swordsmanship. Against this backdrop, sword competitions became popular. In 1974, a portrait brick of “Martial Arts Training and Lectures” was unearthed in Tan village, Gucheng town, Gaochun county, Jiangsu province. This picture composed of two parts shows the teaching of swordsmanship. On the upper left, a man with a sword in his hand makes a step steadily. Another man wearing an official costume is wielding a sword with his right hand, ready for a leap. In the lower part, two adults stand face to face, each with a bamboo book in their hands. It seems that they are teaching swordsmanship. Between them is a child who is listening attentively to what they said. This picture vividly describes how teaching, learning and practice are related in martial arts through unique composition and creative design, creating a harmonious scene of dynamics and statics, and large and small elements. Weapons are indispensable in martial arts performances. InTheBook Shiming Shibing (Explanation of Names: Weapon Names), Liu Xi, a scholar of the Han Dynasty, described the shape ofGouxiang, a unique weapon in the Han Dynasty like this “The pointed parts at either end of the weapon are calledGou(hooks for launching attacks) while the plate in the middle is calledXiang(a shield for defense). People can either useXiangto defend themselves or throwGouto attack enemies in the battle. It is a very useful weapon that can be used either for attack or defense in a battle” (Liu, 1985, p. 113). There are also many images on portrait bricks reflecting armory in the Han Dynasty, also called “Jianqitu”(Picture of armory).

Ficture 4. Portrait bricks of “Sword Dance at a Banquet” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, collected in the Sichuan Museum

For example, the portrait brick of “Wuku” (armory) collected in the Sichuan Museum (see figure 6) exactly reflects this scene: An armory designed as a five-ridge house is built on a platform base, with a rosefinch decorated on the main ridge. The armory is propped by three pillars, a typical bracket structure, comprising one bracket and three pillars. A weapon rack is set up indoors, on which two pieces ofJi(a Chinese polearm combining a spear and a dagger-axe) and three pieces ofMao(a spear) are placed horizontally, and one piece ofGong(a bow) hangs on the left pillar. There is a house on the right side of the armory, with three desks in it. Below the desks hang some weapons. There are footpaths leading to two rooms. The whole image looks like an architectural plan that gives us a full picture of the armory. Weapons, as the basis of the martial arts, have evolved with the times from the originalGe(a Chinese dagger-axe),Ji(a Chinese polearm),Yue(a Chinese large axe), Mao (a spear),Fu(an axe),Dao(a Chinese single-edged sword),Jian(a Chinese double-edged sword), andSha(a Chinese polearm that consists of a two-edged sword attached to a stick) during the Shang and Zhou Dynasties to other types. Since the Qin and Han Dynasties, with the development of ancient iron smelting technology, weapons have become increasingly diversified. According to the unearthed cultural relics, weapons in ancient China can be divided into the following types: hooking weapons, such asGe,Ji, andWugou(a curved single-edged sword in the Spring and Autumn Period); sword-like weapons such asMao,Jian,Sha,Cha(a trident-like weapon with three metal spikes mounted on a long wooden shaft) andKu(a hammer-like weapon); chopping weapons, such asDao,Yue(a battle-axe used in ancient China) andFu; smashing weapons, such as sticks, whips, and hammers; protective weapons, such as arm armor, bracelets and shields. These weapons have laid a solid foundation for the development of modern martial arts. Images on the portrait bricks of the Han Dynasty serve as evidence of the two attributes of fencing in the Han Dynasty, and as an important reference for us to learn about the origin and development of various Chinese martial art events.

Wushu, also known asGuoshuorWuyi, is a technique of fighting and using weapons. It is a traditional Chinese sport with an early origin, a long history, and far-reaching influence, and one of the outstanding cultural heritages of the Chinese nation. Up to now, it is still active in the world where there are Chinese, with a very broad mass base.

Figure 5. Portrait brick of “Martial Arts Training and Lectures” unearthed in Tan village, Gucheng county, Gaochun District, Nanjing, Jiangsu province

Archery

Figure 6. Portrait bricks of “Wuku” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, collected in the Sichuan Museum

Archery is one of the ancient competitive sports in China. The bow and arrow came into being amidst the conflict between human beings and nature in ancient times and for protecting personal safety. They were then widely used in ancient wars. In 1963, archaeologists found flint arrowheads at the relics of the Late Paleolithic Age about 28,000 years ago in Zhiyu village, Shuo county, Shanxi province, proving that humans began to use bows and arrows early on. During the pre-Qin Period, the “six arts,” namelyLi(rites),Yue(music),She(archery),Yu(chariotry),Shu(calligraphy) andShu(mathematics), are regarded as the main teaching contents. We can see that archery is an important subject in the ancient Chinese educational system, and also an important sport in ancient times. In the Zhou Dynasty, the archery rite, a kind of ceremonial archery competition, was established. It was a must-have activity on many ancient occasions, such as the sacrificial ceremony and emperor worship ceremony. Archery comes in four types according to the levels, namelyDashe(the archery ceremony held by the emperor and vassals before participating in the sacrificial ceremony),Binshe(the archery ceremony held when vassals went to the court to pay their respect for the emperor),Yanshe(the archery ceremony held during a banquet), andXiangshe(the archery ceremony held after officials got a higher rank). Since then, archery became a cultural ritual. In the Han Dynasty, archery and hunting were advocated by emperors and nobles. Emperor Wu of Han was keen on hunting with the bow and arrow on a horseback in the forests. Sima Xiangru, a literary master in the Han Dynasty, once “composed an essay concerning the hunting of the emperor” (Records of the Grand Historian, 1982, p. 3002). In the Han Dynasty, the autumn archery competition was held annually in the frontier regions. For this competition, a system has been formed since the 7th year of Emperor Wu’s reign. There were two types of archery in the Han Dynasty:Bushe(shooting on the ground) andQishe(shooting on a horseback).Bushewas further divided into three subtypes includingLishe(shooting in a standing posture),Guishe(shooting in a kneeling posture), andYishe(shooting by tying a thread on the arrow).

On the portrait bricks of the Han Dynasty, archery is depicted on many themes such asLishe. A portrait brick concerning archery practice, collected in the Sichuan Museum, shows how the archers are practicing their archery skills. In the picture, the man on the left side wears a hat and a robe, with a girdle around his waist. On his girdle hangs an arrow box, with three arrows in it. The arrowhead is pointed towards his back. With the bow in his right hand and the arrow on the string in his left hand, he is ready to shoot. The man on the right wears a headscarf and a long robe, with a girdle around his waist. He holds a bow in his right hand while an arrow on the string in his left hand, and is also ready to shoot.

Figure 7. Portrait brick of “Archery Training” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, collected in the Sichuan Museum

Figure 8. Portrait brick of “Hunting with the Bow and Arrow” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, collected in the Sichuan Museum

Judging from the costumes in the picture, we can infer that the two were professional archers. This picture vividly depicted the training movements of the archers.Lisheis the mainstream of traditional Chinese archery. Since the Han Dynasty, this form of archery has been flourishing all the time.Qishe, also known asMashe(shooting on a horseback), was originally the custom of the ancient northern minorities. During the Warring States Period, King Wuling of Zhao carried out military reforms and ordered his people to wear the Hu-styled attire and practice shooting on a horseback. Later, it was replicated by other states during that period.

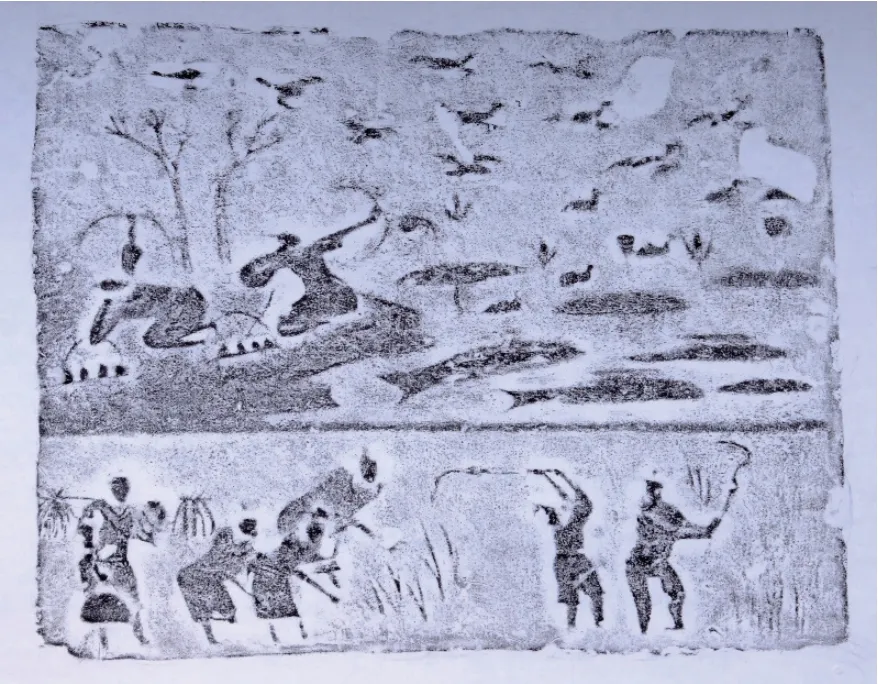

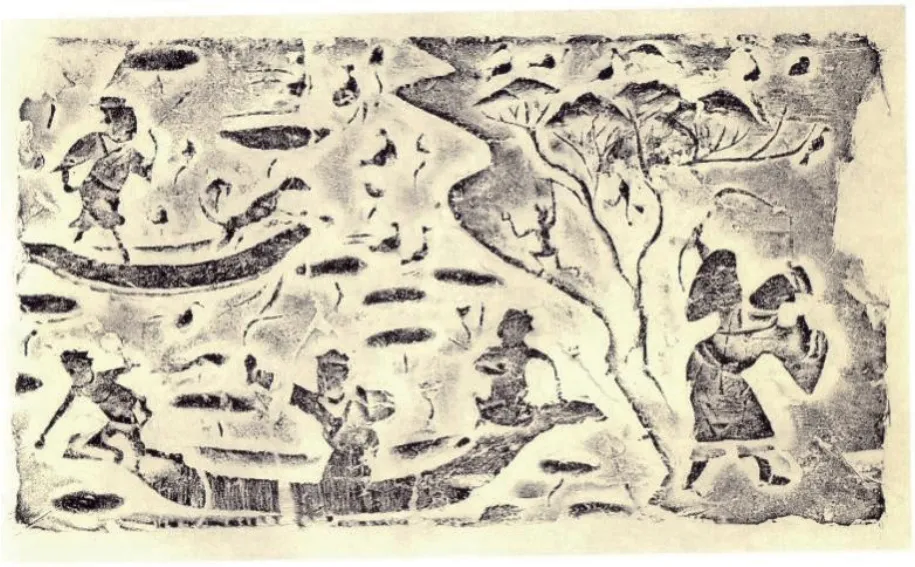

In the Han Dynasty,Qishebecame the most important form of martial arts in military activities aiming to crusade against the Huns. As shown on the portrait brick of “Hunting with the Bow and Arrow” in the Eastern Han Dynasty collected in the Sichuan Museum (see figure 8), the technique used by the man on horseback is calledQishe. In the picture, the man on the upper left wears a pair of boots with his trouser legs tucked in. He stretches his right hand forward and holds a trident with a long handle in his left hand. He raises his right leg and pushes against the ground with his left leg, ready to throw the trident to kill the prey. Beneath him are four galloping hounds, followed by a rider on a swift horse, who is bending his bow to shoot the prey. This dynamic picture shows the archer’s ability to keep his prey within the shooting range of his bows while galloping on the horse. This demonstrates his brilliant archery skills. From the portrait brick of “Harvest &Yishe” unearthed from the Han Tomb in Yangzishan Mountain, collected in the Sichuan Museum (see figure 9), we can feel the distinctive rural elements of the Chengdu Plain in the Han Dynasty. The brick is divided into upper and lower parts. In the upper part, there is a rippling pond, in which fat fish and wild geese are swimming and foraging freely. The pond is full of lotus flowers in full bloom, with lotus leaves floating on the water. In the shade of a tree by the pond hide two hunters in broad-sleeved long robes. They are kneeling on the ground with bows and arrows in their hands. One man lies on his side with the bow and arrow in his hand aimed at a wild goose flying in the sky. The other man leans backward slightly and raises his arm, waiting to shoot the geese with a full bow. In the open space beside them, there is a semi-circular wooden frame to placeZhuo(bow string) orZeng(short arrows) for each archer. Over the pond, a dozen wild geese are flying in panic and fleeing in all directions. The lower part of the brick shows a different scene: A group of farmers are working in a field. On the right side, two bare-chested and bare-footed men in shorts are waving long sickles to harvest grain. Behind them are two men in dark-colored coats and a woman in a long dress. They are bending over and picking up the cut ears of grain in the field. Another man carrying a shoulder pole and holding a food ware in his hand is about to leave.

Figure 9. Portrait brick of “Harvest & Yishe” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, collected in the Sichuan Museum

Judging from the costumes and behaviors, the two hunters in the upper part of the picture are obviously not ordinary hunters. In the lower part of the picture, it shows the working scene of ordinary peasants, who are working hard in the hot sun with their sleeves rolled up and their feet bared. They even stay in the field while eating and drinking. It is quite different from the leisurely scene in the upper part of the picture.

Since the middle of the Han Dynasty, as land annexation became more and more serious, there emerged a large number of powerful landlords across the country. In the estates of these powerful landlords, there were fertile fields, luxury mansions, carriages and horses, pastures, armory, weaving machines and wine-making workshops, and even salt wells and smelting workshops. In theBook of the Later Han, Fan Ye described it as follows: “The powerful landlords have hundreds of mansions, plenty of fertile fields, thousands of slaves and maidservants, and tens of thousands of servants forced to cling to them. Their ships and carriages are traded across the country. They hoard goods at a low price and sell them at a high price. Such scenes are very common to see in the capital city.” Since they possessed such large estates, landowners needed to hire a large number of slaves and tenant peasants to do production work for them. In order to make a living, the peasants who had lost their land had to work in the manors of the landowners. On this portrait brick of “Harvest &Yishe,” it can be seen that there are as many as six peasants working and harvesting in the field. Judging by this, they are more likely to be coolies in a landlord's manor than laborers of an ordinary peasant family. The hunters with bows and arrows were probably the owners of the manor since they are the only ones who can shoot for fun during the busy harvest season. Perhaps it is because the pond and the field in the picture are owned by the landlord that these two different scenes were painted on the same brick. This reflects the cruel reality of land annexation by the powerful landlords and the arduous life of peasants in the Eastern Han Dynasty.

The portrait brick of “Harvest &Yishe” mainly shows the technique ofBushe. In the shadow of the left tree, there are two archers who are bending their bows to shoot. Besides them are two little shelves with fourBos(an ancient stone arrowhead attached to a string used for shooting birds). According to theRadical of ShiinShuowen Jiezi(an ancient Chinese dictionary of the Han Dynasty), “Bois a kind of stone arrowhead attached to a stick with a string for shooting birds” ( Xu et al., 2007, p. 466).①(Han) Xu, S. Shuowen Jiezi (reviewed by [Song]) Xu, X., et al.). Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House. First edition, August 2007, p. 466.This archery method was also calledZhuosheorYishein ancient times, both using arrows tied to a string. It can be seen in the picture that the archer is aiming his arrow at a wild goose in the sky, with his eyes, the arrow and the wild goose in a line. This fully and vividly shows the pulling strength and the shooting accuracy of the archer.Yisheusually refers to short-distance shooting withZeng(an arrow tied to a string that can be recovered for reuse) rather than long-distance shooting. InStrategies of the Warring States: Strategies of Chu, it is recorded that “the archer was preparing his stone arrowhead with a string and black bow to shoot the vertin in the sky,” which reflects the popularity ofYisheat that time. In theChuzhen (Activating the Genuine) of Huainanzi (Master(s) from Huainan), a collection of various philosophical treatises compiled under the mentorship of Liu An, Prince of Huainan during the middle of the Former Han period, there is also a record of “shortdistance shooting withZeng,” indicating that the Han Dynasty inherited this form of hunting.Yi She, also known asZhuoshe, is a way to shoot birds by tying a string on a short sword as the arrow so that the hunter can retrieve both the arrow and the prey shot.Yishemay have appeared as early as in the Warring States Period, and evolved into a form of entertainment for the upper class in the Han Dynasty (Cui, 1999).

Ancient Sports Games for Both Self-Cultivation and Entertainment

The Chinese sports culture, full of distinct Oriental characteristics, echoes the values embedded in Chinese culture. Influenced by the philosophy of “Unity of Man and Nature,” ancient Chinese people not only pursue physical health but also spiritual health through sports activities. Therefore, some recreational folk activities have been gradually integrated into sports activities.

Liubo (an Ancient Chinese Board Game)

Figure 10. Picture of “Liubo,” collected in the Sichuan Museum

Liubois one of the oldest chess games in ancient China. In this game, each player has six game pieces that are moved around the points of a square game board that has a distinctive and symmetrical pattern. Moves are determined by the throw of six sticks that act as dice. According to theRadical of ZhuinShuowen Jiezi, “Bois a kind of chess game with 12 game pieces and six sticks” (2007, p. 223). It might be created during the Spring and Autumn Period and became quite popular during the Warring States Period. As is recorded in theAnalects of Confucius: Yang Huo, “It is hard to go anywhere if you just stuff yourself with food all day and do nothing meaningful! Wouldn't it be better to try and play the chess game?” (He, 2007, p. 357). During the Qin and Han Dynasties, the game ofLiuboentered its prime age and became one of the most popular chess games favored by the court and the folk. In theZhenshuoofLunheng, a philosophical treatise written by Wang Chong in the Later Han Period, the author once exclaimed that “if a man does not study the classics, he must be always seeking comfort and pleasure” (Wang, 1990, p. 1123). The portrait brick of “Liubo” collected in the Sichuan Museum (see figure 10) vividly depicts the scene when people are playing this game. In the picture, there are four people sitting beneath the valance. They sit in pairs face-to-face, with a chessboard between them. They are playing chess with six sticks on each chessboard. The servants kneel beside the chessboard and lean forward. One of them is raising his hand in surprise. The picture vividly depicts the facial expressions of the chess players and observers. Cao Zhi wrote in his famous poemOde to Deities: “Deities are throwing six sticks on the chessboard to play chess in the corner of Taishan Mountain.” It can be seen that playingLiubohas been regarded as the life of the deities.

Fishing

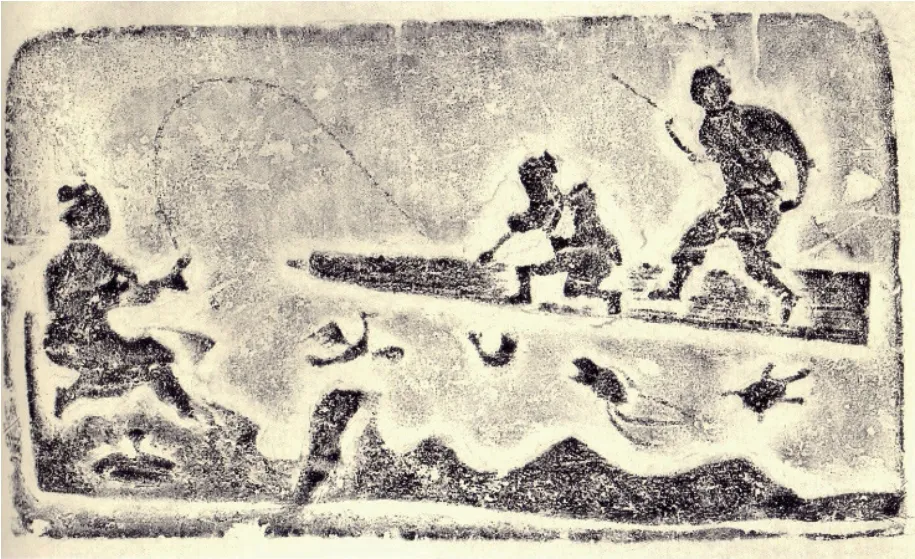

Fishing originating in people’s daily life has existed since ancient times. According toZhonghua Fengwu Tanyuan(An Exploration of Special Chinese Items), fishing in China boasts a history of at least 7,000 years. In 1953, a large number of bone-made fish hooks were discovered in the settlements of Yangshao Culture at Banpo Archaeological Site in Xi’an city, West China’s Shaanxi province, proving that our ancestors in the Neolithic Age had already made a living by fishing. The earliest written records about fishing in China can be traced to theBook of Songs. InCailü(Green Grass Harvesting), it reads, “When he went hunting, I prepared the bow for him. When he went fishing, I prepared fishing lines for him” (2007, p. 198). This indicates that people fished in rivers and lakes with bamboo poles as early as the Spring and Autumn Period and Warring States Period. In history, many literati and scholars were fond of fishing and wrote a large number of poems and essays concerning fishing. For example, inHard Road, Li Bai wrote, “I poise a fishing pole with ease on the green stream Or set sale for the sun like the sage in a dream.” The portrait brick of “Fishing Raft” (see figure 11), collected in the Guanghan Museum of Sichuan province, vividly describes the scene of fishing: In a wide river, a man is rowing a raft with a pole in the river, while turtles, shrimps, fish and ducks are wandering underwater. In the middle of the raft kneels a man who seems to hold a line in his hand and at the end of the line there seems to be a fish.

Figure 11. Portrait brick of “Fishing Raft,” collected in the Guanghan Museum in Sichuan province

Figure 12. Portrait brick of “Picking Lotuses, Hunting and Fishing,” collected in the Sichuan Museum

On the rolling river bank squats a man who seems to be fishing as he is holding a pole and casting a line. In this vivid and beautiful picture, the four movements of holding the pole, throwing the line, lifting the line and collecting the fish are delicately depicted, giving a special appeal of romanticism. In contrast, the portrait brick of “Picking Lotuses, Hunting and Fishing,” collected in the Sichuan Museum (see figure 12) highlights the fun of daily life by arranging fishing and hunting in the same picture. Today, fishing has been prevailing all over the world as a fun and elegant activity that exhibits the wisdom and benefits the health of the fishermen.

Horsemanship

Horsemanship, also known as equestrianism orYu(riding a horse), generally refers to horse riding skills. It is related to many sports activities in ancient China such as horse racing and circus. Just like archery, horsemanship is one of the Six Arts.

Horsemanship was originally invented for hunting and was later introduced in military activities. Due to its important role in hunting and military activities, horsemanship has always been valued by people and gradually developed into a sports activity. Horsemanship appeared early in China and can be traced back to the early Zhou Dynasty or the late Shang Dynasty. According to archaeological data, horsemanship was first invented by nomads living in north China. As recorded in theCommentary of Zuo on the Spring and Autumn Annals, “The north area of Jizhou is home to horses, and has no new ruler ” (1987, p. 656). In the ancient Central Plains, horse training and carriage driving appeared in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties, during which horse-drawn chariots were also used in battles. In 305 BC, in order to fight the Huns in the north and the State of Qin in the west, King Wuling of Zhao carried out a reform of “Wearing the Hu-styled Attire and Shooting from Horseback in Battle” and changed the philosophy of fighting on horse-drawn chariots to fighting by riding horses. The emergence of cavalry imposed higher requirements on horsemanship. As horsemanship became more and more popular, it was included as part of the test to assess the skills of soldiers. Horse racing became very popular as early as the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. Sima Qian recorded the famous story of “Tian Ji’s Horse Racing Strategy” in theRecords of the Grand Historian. In the Han Dynasty, with the wide use of carriages, horsemanship became an important form of physical training. In theHan Jiuyi(Ancient rules of the [Former] Han), Wei Hong in the Eastern Han Dynasty described the system of the Western Han Dynasty, “Men enlist in two-year military service at the age of 23. In the first year, they serve as theWeishi(guard) for preparatory training. In the second year, they serve asCaiguan Qishi(a member of the local reserve army). During their military services, they need to practice archery, horse- and chariot-riding, and arrangement of battle arrays” (1990, p. 81). It can be seen that noble men were required to learn the skills of archery and horsemanship at that time.

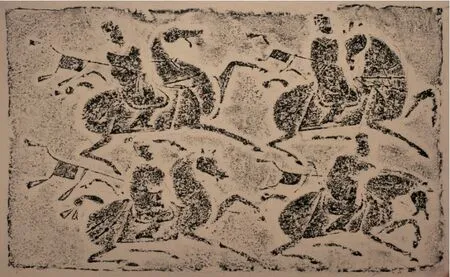

Figure 13. Portrait brick of “Four Officials Riding on Horses with Halberds in Hand” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, collected in the Sichuan Museum

Many portrait bricks of the Han Dynasty described the scene of horsemanship, such as the portrait brick of “Four Officials Riding on Horses with Halberds in Hand” (see figure 13) collected in the Sichuan Museum. In this picture, four officials wearing headscarves and short costumes are riding on the horses, each with a bow on the left side of their waist, and an arrow box on the right side. The horses, though in different postures, always keep the same formation. The bas-relief technique was applied in making this portrait brick to vividly and accurately sketch the brilliant horsemanship of the riders, and the strong bones and the powerful muscles of the horses.

Figure 14. Portrait stone of “Horsemanship” unearthed from the Han Tomb in Beizhai village, Yinan county, Shandong province

The whole picture is full of vitality and trueto-life. The portrait stone of “Horsemanship” unearthed from the Han Tomb in Beizhai village, Yinan county, Shandong province (see figure 14) further illustrates the popularity of horsemanship in the Han Dynasty. In this picture, the horses are galloping with four hooves high off the ground, and a rider, pressing against the horseback with both hands, is flying in the air. This difficult movement shows the consummate horsemanship of the rider. Today, horsemanship is loved by people all over the world as it represents mutual understanding, harmonious coexistence, and unity between man and horses.

Horsemanship has also become one of the most important sports events in international competitions.

Cuju ( an Ancient Chinese Football Game)

Cuju, also known asTaju,Cuqiu, andZhuqiu, is a unique name for ancient Chinese football. As for the origin ofCuju, Liu Xiang in the Western Han Dynasty wrote in his bookBielu(The Abstracts) that “It is said thatCujuwas created by the Yellow Emperor, or originated in the Warring States Period.Cujusymbolized military strength. Soldiers had their military skills improved and talent recognized while they were playingCuju” (1996, p. 2257). According to the archaeological data, the early appearance ofTajuis not only related to primitive hunting, but also to military training. In theStrategies of the Warring States: Strategies of Qi, it is recorded that in addition to music activities, “people in Linzi, the then cultural capital of the State of Qi, were also keen on a variety of games such asDouji( an ancient Chinese game of cockfight),Zouquan(dog racing),Liubo, andCuju.” At that time, various competitive sports, recreational games, and professional cultural groups sprang up, and all kinds of competitive and recreational activities flourished in the city. According to experts, theCujucompetition was originally a six-people game, including aWuzhang(an entry-level officer in the ancient Chinese military rank system) or aGuizhang(an officer in charge of fiveWuzhang) and five soldiers. This game system was closely related to the grassroots military and administrative system involving five people or fiveWuzhangin the State of Qi during the Warring States Period.Cujuwas very popular in the Han Dynasty. It was not only an important means of military training but also a recreational sport favored by high officials and noble lords. Ban Gu included theTwenty-five Articles on Cujuin theBook of Han: Treatise on Literaturefollowing the description of weapons as part of the list of thirteen weapons, making it an important military reference book. As recorded in theKauiji Dianlu(Records of Kuaiji), “In Chang’an city of the Western Han Dynasty, soldiers from ordinary families took archery and horsemanship as their main tasks while in military service and they practicedCujuwhen back at home.” At that time,Cujuwas played either as a recreational activity by one or more people without a special field, or as fierce competition in a special field by following certain rules. The field ofCujuwas about half the size of today’s football field. It was surrounded by battlement-like low walls. Two crescent-like goals (also calledJushi) decorated like small houses are arranged symmetrically at both ends of the field (Ma, 2019, p. 131). A spectator stand was set up right in front of theCujufield with stairs on the left and a ramp on the right. The spectators need to sit down in the left zone according to their social classes. There was a special seat reserved for the emperor to watch the game on the stand. The ramp on the right leads to the left zone. In the Eastern Han Dynasty,Cujubecame so popular among ordinary people that women also participated in it formally. In the Southern and Northern Dynasties, playingCujuon the Cold Food Festival (the day before Tomb-sweeping Day) became a custom in the Chu area. Later, this custom became a national festival in the Tang Dynasty.

The lifelike images of “Cuju” on the portrait bricks and stones of the Han Dynasty vividly recorded the brilliant sports achievements of the Han Dynasty.

Figure 15. Portrait stone of “Drum Dance” unearthed from Shiqiao town, Wolong District, Nanyang, Henan province

Figure 16. Portrait stone of “Wuyue Baixi” (“Banquet Dances and Acrobatics”) collected from Dongguan subdistrict, Nanyang, Henan province

On the portrait stones,Cujugenerally appears together with music, dance, and acrobatics. Both men and women can participate inCuju. They usually playCujuas they dance. The most common scene is one player playing with one ball. Sometimes, one player may also play with two balls, or two players each play with one ball. These are all for entertainment and are somewhat different fromCujugames or sports for competitive purposes.Cujugames have enriched the forms of performance of the Han Dynasty. This also reflected the popularity ofCujuat that time.

In 1935, the portrait stone of “Drum Dance” was unearthed from Shiqiao town, Wolong District, Nanyang, Henan province (see figure 15). In the picture, a drum decorated with colorful feathers is placed between two performers. The performer on the left is playingCujuwith elegant dance moves while the one on the right is beating the drum with a drumstick. On the portrait stone of “Wuyue Baixi” (“Banquet Dances and Acrobatics”) collected from Dongguan subdistrict, Nanyang city, Henan province (see figure 16), several performers are showcasing their skills. The two performers in the middle stand out from the others. One is standing upside down on a wine ware with one hand, while the other is dancing by stepping on one of the three balls with his long sleeves extended in the air. This depicted theCujuperformance in banquet dances and acrobatics (Liu, 2019, p. 181).Cuju, as a sport that emerged from the folk, was vividly and neatly depicted on the portrait stones, creating an impression of boldness and roughness. From these stones, we can directly perceive the enthusiasm and desire for performance of the participants. At present, the portrait stones with images ofCujuwere only discovered in Henan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Shaanxi, and Zhejiang provinces. In Sichuan province, no such images have been discovered. However, the images of drum dance appeared many times on the unearthed portrait bricks in this area, which are similar to the images ofCuju. Since there are some similarities between the two kinds of images, it is easy to confuse them.

To clarify this problem, we paid a visit to the Nanyang Stone-carved Art Museum in the Han Dynasty where the portrait stone of “Wuyue Baixi” is exhibited to identify the ball-like things besides the feet of the long-sleeved dancer.

Tsarevitch Ivan sat on the Gray Wolf s back and took Helen the Beautiful in his arms, and the Wolf began run- fling more swiftly than fifty horses, across the three times nine countries, back to the Tsardom of Tsar Afron. The nurse and ladies-in-waiting of the Tsarevna hastened to the Palace, and the Tsar sent many troops to pursue them, but fast as they went they could not overtake the Gray Wolf.

When we saw the physical object, we immediately confirmed that it is indeed a roundCujuball.

Therefore, it can be asserted that the portrait stone in figure 16 indeed depicts theCujuperformance by a long-sleeved dancer.

Acrobatics

Acrobatics is a kind of performance skill. Its earliest historical records date back to the Warring States Period. It is said that there was a man named Xiong Guanliao who was good at playing with balls and could keep seven to nine balls in the air with both hands. The Han Dynasty witnessed the formation and development of Chinese acrobatics. In this period,Juediperformances have improved in content, variety, and skills, and finally evolved into a new form of performance art centering on acrobatics and integrating all kinds of performing skills.

From the unearthed portrait bricks and stones, it can be seen that acrobatic programs in the Han Dynasty had entered the stage of systematic development. Many of the programs, such as handstands, somersaults, jujitsu, ball dancing, and wheel dancing, all require highly difficult physical skills. Some of them have evolved into modern competitive sports, such as acrobatics and horizontal bar gymnastics. Some highly difficult techniques in acrobatics are also referenced in the training of modern competitive sports (Qiao, 2015, p. 93).

Therefore, tracing the origin of acrobatics, we find that it is closely related to sports, and is one of the important driving forces for sports development. For example, skill performances such as handstands and somersaults can be found in modern sports. The portrait brick of “Plate Dancing” (see figure 17) collected in the Sichuan Museum displays a dancer performing handstands on tall plates. In this picture, a woman dancer on the left is standing on a 12-tier plate and performing bending, which is a quite difficult technique. Zhang Heng, a scholar in the Eastern Han Dynasty, once mentioned the difficulties and risks in acrobatics in his bookXijing Fu(Ode to Xijing): “A young child is showing his talents, rolling up and down around a hanging pole. Suddenly he makes his body upside down by hooking the pole with his heels. It seems that he might fall to the ground at any time, but he successfully grabs the pole again at the critical moment.” This is no exaggeration.Zhuangji,Zousou(walking on a rope), andXiche(acrobatics on a carriage) all belong to aerial performances. The portrait brick of “Xiche” unearthed from Xinye County in Henan Province (see figure 18) shows that performance around a hanging pole was prevailing in the Han Dynasty. In this picture, there are two carriages that are connected with each other. On each carriage stands a pole. On the front carriage, there is a man hanging upside down with his heels hooking the pole. On each of his outstretched arms stands a child who is performing skills. On the rear carriage, a man is squatting on a high pole with one hand holding one end of a long rope. The man on the front carriage is holding the other end of the rope. Both men tension the rope to form a slant angle as a third man is walking calmly on it. This kind of performance is difficult to complete and poses high risks. It requires not only adept skills and high strength but also courage and determination of the performers. Some of the acrobatic movements in the image have been preserved until today. A picture (see figure 19) is carved on the stone coffin in a cliff tomb in Yibin city, Sichuan province. In the picture, one person is holding a ring, and another leaping through the ring. It can be inferred that this person must roll forward after leaping through the ring and landing on the ground with both hands. The movement of rolling was calledChongxiain the Han Dynasty. Zhang Heng described this movement in hisXijing Fu, “The performer easily jumps through a ring pierced by sharp knives inside as if he were a nimble swallow flying swiftly over water.” It describes the performer’s forward tumbling movement as swift and neat as a swallow flying over water. Numerous acrobatic images on the portrait bricks and stones have fully demonstrated the Han People’s proficiency in controlling their weight, maintaining the balance of the body, and mastering various skills and movements. We modern people cannot help but be amazed by their skills.

Figure 17. Portrait brick of “Plate Dancing” in the Eastern Han Dynasty, collected in the Sichuan Museum

Figure. 18 Portrait brick of “Xiche”unearthed in Xinye county, Henan province

Figure 19. Stone coffin in a cliff tomb in Yibin, Sichuan province

Conclusions

The competitive sports of the Han Dynasty experienced twists and turns during their development and played a vital role in the development of modern Chinese competitive sports. They are the product of the wisdom of ancient Chinese people in pursuit of their dreams. They convey information about history, culture, and society in a way that is beyond comparison in other fields. The portrait bricks and stones of the Han Dynasty show us how the competitive sports culture developed during that period. It is a concrete manifestation of the profound traditional Chinese culture, and also the most valuable material for studying ancient competitive sports culture.

Sports culture, in general, refers to all sports-related achievements made by people in sports activities, including material and spiritual achievements. Sports activities largely exist in the life and work of ancient Chinese people, such as ceremonial activities, martial arts activities, military activities, and farming and sericulture activities. Moreover, various games and folk activities popular among ordinary people, such as dragon boat racing, tide riding, and acrobatics, all belong to sports culture.

Although China boasts a splendid history and rich legacy of competitive sports, it is difficult for us to reproduce the scene in which our agile ancestors sweat in sports activities as time goes by. Thanks to the portrait bricks and stones of the Han Dynasty, we can have a glimpse of the development of competitive sports during that period. Such bricks vividly captured the sports activities participated by our ancestors in the Han Dynasty, giving us a full perception of the competitive sports spirit of the Chinese nation.

In its long course of development, competitive sports have gradually evolved into an extensive range of group activities that reflect the independent character and unique aesthetic values of the participants. Therefore, ancient Chinese sports culture is of great reference significance for the sustainable and healthy development of modern sports. By studying the development and new implications of ancient Chinese sports culture, as well as its correlation with social activities, we can better understand ourselves and accomplish further self-discovery and self-improvement, thus contributing to the building of a “healthy China” that is strong in sports.

杂志排行

Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- Determination of Relationships and Allocation of Responsibilities—Taking the Adjudication of Household Service Contract Disputes as an Example

- Tri-Engine Structure and Industrial Composition of Cultural Productivity

- Full Empowerment and the Participatory Governance in Rural Communities: A Comparative Study Based on Two Cases

- Measurement and Spatial Difference Analysis of Innovation-Driven Urban Development Levels in Sichuan Province

- Stock Market Turnover and China’s Real Estate Market Price: An Empirical Study Based on VAR

- Research on the Impact of the Pension Insurance System on the Optimization of the Consumption Structure of Rural Families