Full Empowerment and the Participatory Governance in Rural Communities: A Comparative Study Based on Two Cases

2022-08-24ChengShuling

Cheng Shuling

South West University of Finance and Economics

Huang Jin*

Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences

Abstract: Participatory governance is a feasible method in the context of a need for effective governance. With the introduction of participatory governance, the focus has shifted to how to empower. A comparative study of two cases in this paper finds that full empowerment is the key to effective governance in participatory governance. Full empowerment can motivate a community to participate through the empower of rights and resources and can improve community participation capacity through the introduction of technical services. The full empowerment encourages a community to undertake its due responsibility and thus forms a mechanism of the simultaneous downward shift of right and responsibility; the refined technical services enhance community participation capacity and thus develop the mechanism of self-management and adaptation, and the interactions between multiple agents produces a coordinating mechanism for government empowerment and community acceptance.

Keywords: participatory governance, full empowerment, community participation

China uttered its first call for the modernization of the national governance system and capacity at the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee in 2013.①Communiqué of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. Retrieved from http://news.12371.cn/2013/11/12/ARTI1384256994216543.shtmlThe Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Implementing the Rural Revitalization Strategy, the “No. 1 central document for 2018,”②The “No 1 central document” is the name traditionally given to the first policy statement of the year released by the central authorities, and is seen as an indicator of policy priorities.went further to propose “effective governance” in rural areas.③Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Implementing the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-02/04/content_5263807.htm?isappinstalled=0The “No. 1 central document for 2022” listed highlighting practical results in improving rural governance as one of the eight key tasks for comprehensively promoting rural revitalization.④Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Comprehensively Promoting Rural Revitalization in 2022. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-02/22/content_5675035.htmThrough the practice, participatory governance provides a path for local governments in their governance system innovations. So what factors affect the participatory governance of rural communities and how to carry out it? This question is worth studying.

Literature Review and Problems

Participatory governance originated in the 1990s and was mainly used for the protection of global natural resources. In recent years, it has been gradually introduced into the fields of political, economic, and social development, especially at the level of local governance. On the one hand, the development of participatory governance has a theoretical origin in participatory democracy; on the other hand, it has its own needs, and has begun to seek new governance schemes in the “growing fascination with governance mechanism as a solution to market and/or state failures” (Jessop, 1998).

Participatory governance has been extensively studied overseas, with a focus on “empowerment” and “participation.” What is empowerment? Archon Fung and Erik Olin Wright defined participatory governance as a process of empowerment, which empowers individuals or organizations who have a stake in pertinent policies and expands their participation in the decision-making of public policies. Stakeholders need certain empowerment from the government when they participate in coordination and negotiation with the latter, and such empowerment is the core and important premise of participatory governance (Patsias, Latendresse & Bherer, 2013).

Who are the participants? First, the participation involves multiple agents, including individuals, non-government organizations, enterprises, and government departments. Second, participation must include participation in decision-making so those affected by the decision-making, especially the marginalized and disadvantaged groups, can effectively join the governance process. This increased participation is expected to improve the understanding of ordinary individuals in the areas of psychological, technical, and procedural levels, and thus contribute to the participatory process (Yuan, 2011, p. 108). Third, participation is a premise for governance, and it is through such participation that government and society develop a relationship of mutual trust and cooperation and thus form a new foundation for governance (Sun, 2004, p. 26).

Chinese scholars have different focuses in their understanding of participatory governance. Wang Xixin (2010) defines participatory governance from the perspective of administrative decisionmaking, emphasizing people’s participation in the government’s public policies. Zhang Jingen (2014) accepts the definition of “empowered participatory governance” proposed by Fung and Wright, focusing on the empowerment to the public. Despite these varying emphases, most scholars agree that participation, empowerment, and multi-agent consultation and cooperation are the keys to the understanding of participatory governance (Rao & Chen, 2014; Chen & Zhao, 2009; Fang & Xu, 2015; Liu, 2014). We explain participatory governance from the perspective of empowerment. Agreeing with the definition by Fung and Wright, we view participatory governance as a process of empowering individuals and organizations who have a stake in public policies and expanding their participation in the decision-making regarding such policies. We hold that empowerment in participatory governance is the premise for the participation of concerned individuals and organizations, and also the source of motivation for the participation of such individuals and organizations. Empowerment plays a decisive role in participatory governance.

The accumulative research on participatory governance by Chinese scholars can be seen from two aspects: The first is the introduction of the concept of participatory governance, including its theoretical origin and the status quo of its development in foreign practice; and the second is the study of the participatory governance in China. In particular, the practice of participatory governance includes the following: first, the classification of participatory governance, including self-governance for villagers, community-level self-governance, and participatory budgeting (Fang & Xu, 2015; Chen & Zhao, 2009); second, the function of participatory governance. Scholars usually start with the relationships between the state and society, believing that participatory governance can help in improving the scientific and democratic decision-making and public participation (Rao & Chen, 2014; Liu, 2014); third, the discussion about the factors behind the operation of participatory governance, including the support and guidance of local governments, the active participation of non-governmental organizations and scholars, and the positive civic culture (Wang, 2010; Rao & Chen, 2014; Zhao, 2015), and the local cultural background (Heinelt & Smith, 2003); and fourth, the universal problems such as insufficient empowerment (Chen & Xu, 2013), insufficient social participation and insufficient capacity for action that scholars have found from the perspective of practice (Chen & Xu, 2013; Hu, & Xiang, 2014; Fang & Xu, 2015).

As scholars have found, insufficient empowerment is caused by the following factors. The first is the insufficient legal empowerment. Taking the innovation of basic-level governments in public decision-making represented by participatory budgeting as an example, one can find that the restriction on public power at the grassroots level is not abundant. The second is the the pressure system of administrative operation. Empowerment may slow down a lower authority’s step to meet the demands from the higher level (Fu & Wang, 2011). The third is the insufficient capacity for community participation, which includes an inadequate capability for individual participation, and inadequate capacity for organizational participation (Hu & Xiang, 2014). The fourth is the an insufficient supply of external resources (Hu & Xiang, 2014), or weak motivation for community participation caused by limited participation space (Zhang, 2016).

After further exploration, however, one can find a conflict between the concept of participatory governance and the current governance structure. The traditional rural community governance in China used to be mainly clan and squire governance. Since the implementation of the household contract responsibility system, the rural areas in China have restored their family-based “selfsufficiency,” and at the same time, a large scale of population outflow has reduced the capability of self-governance, and the villager self-governance system attaches more importance to election rather than governance in its implementation. All these have resulted in a series of problems.

Participatory governance requires the government to take the initiative in distributing empowerment while the community must take the initiative to participate. Fragmentation occurs within the community resulting in dependence on the government, low willingness to participate, and insufficient ability to participate.

As a result of such conflict between concept and reality, there is still a huge space to explore the localized practice of participatory governance, and scholars are putting forward suggestions from different perspectives. At the macro level, according to their reports, we should improve the status quo of empowerment through legal empowerment and institutional design (Zhang, 2014; Fang & Xu, 2015). At the micro level, it is advisable to encourage the participation of social organizations and experts (Chen, & Xu, 2013; Liu, 2014) cultivate community self-organization, and develop their capability to participate (Hu & Xiang, 2014; Fang & Xu, 2015) and respect for the local cultural background (Zhao, 2015).

Responding to the academic circles’ appeal and the government’s change in governance mode, many local governments have gradually built the awareness of “empowerment” and performed relevant activities, taking the initiative to try participatory governance. The crux has shifted from whether to empower 20 years ago to the present question of how to empower. This paper argues that full empowerment is a key factor behind participation governance and that full empowerment means that the basic government grants comprehensive resources and rights to the public in the practice of community-level participatory governance, and at the same time provides the refined service required for effective governance, to effectively improve community governance. Here, the term “resources” refers to funds or materials provided by the government, the term “rights” to the right of management granted to community-level self-governance organizations, and the term “refined service” mainly to the externally offered training and support of relevant skills concerning participation, organization, and management in the practice of community self-governance. The following discussion is mainly based on the cases of participatory governance with two county-level governments’ active empowerment, and through a comparative study of the empowerment carried out by county-level governments in participatory governance. We will delve into the conditions of full empowerment and the practical mechanisms needed for effective rural governance.

An Overview on the Cases and the Train of Thought for the Research

An Overview of the A County Community Development Fund Project

A county implemented the project of poverty alleviation in 2007, one of whose sub-projects is the industrial alternative development project. In the original project design, villages were supposed to submit their plans for industrial alternative development to the township or town authorities, and those at the county level to review and distribute funds and implement the plans. After the first round of implementation in 2007-2008, the Poverty Alleviation and Immigration Office found that after the community purchased tree seedlings or distributed fertilizer to the farmers, some seedlings did not grow, and the project was not ideal.

From 2008 to 2009, the Poverty Alleviation Office of A county cooperated with G Community Development Center to run the industrial alternative development fund under the project by means of participatory governance and established community development funds, which were finally applied for by 27 deprived villages. The county poverty alleviation office provided 150,000 to 320,000yuan, and the G Community Development Center was in charge of capacity building and technical support, with the project accomplished in two phases within four years. By the end of 2020, 25 of the 27 community funds had been operating normally, while the other two communities retained the project principal without starting the project. The principal of the project has risen from 7.64 millionyuanto 9.7 millionyuan, an increase of more than 2.06 millionyuan. Accordingly, the accumulative loans for this project accounted for nearly 44.32 millionyuan, with 5,796 farming households benefitting in total.①Data from G Community Development Center.

We studied L village as a key analysis case. This village is about 8 kilometers away from the county seat, enjoying good public transport. It consists of 263 households in four groups, with a population of 973. The main incomes of the villagers come from the growing of crops, fruit trees, and migrant work outside of the village, averaging 10,000yuanor so for each person in 2019. L village received the training in community development funds in 2009, and registered itself as a cooperative legal person and opened a bank account in 2010. In 2012, the village officially entered the operational stage of villager loans, which has been running well so far with a net increase of about 100,000yuan. The entire process of the community fund development in this village is representative, for it has encountered the typical difficulties of reluctant candidates, delayed repayments, and changes in rules, but the community fund in the village runs smoothly in general, and the person in charge of the community fund gradually gained trust among the villagers and was elected the director of village committee in the end, so the growth of the management in the entire project operation is also representative.

Overview of Collective Forest Tenure Reform and Forest Eco-Compensation Project in B County

B County is a big forest county. The provincial forestry department in charge of B county issued an opinion on promoting the reform of the collective forest tenure system in 2007, instructing, “In the case of mountains under a collective’s unified management, the mountain forests that the masses are fairly satisfied with and unwilling to divide can remain under the collective’s unified management, but the operational mechanism should be changed under the principle of ‘division of shares without the division of the mountain, and distribution of profits without the distribution of forests,’ adopting shareholding cooperation and averaging shares and profits to each household.” B county accomplished its forest tenure reform by following the principle of “division of shares without the division of the mountain, and distribution of profits without the distribution of forests.” It began to allocate ecological compensation funds in 2011. For the better management of the forest eco-compensation funds, the Forestry Bureau of W county, urged by an incumbent deputy county mayor of this county, took each administrative village as a unit to set up management boards of collective forestry shares, with each board in charge of the management of those ecological compensation funds and collective forests. The compensation funds followed the Provincial Department of Finances’ 2014 provincial ecocompensation standard of collective non-commercial forests, accounting for 16.09225 millionyuaneach year, with 14.75yuanfor eachmu.

We selected X village in B county for this case study. This village is 20 kilometers away from the county seat, with an area of 25.1 square kilometers and an average altitude of more than 2,800 meters. It is populated by 148 farming households and has an agricultural population of about 500. The income of villagers mainly comes from agricultural production, livestock breeding, medicine collection, and migrant work. This village has 11,938.9muof collective forest with eco-compensation, and the annual eco-compensation fund is 173,114yuan, with 10 percent to be set aside for public uses, which is according to the 10 percent ratio. The Forestry Bureau and the social organization S began to cooperate in 2013, selecting this village to experiment with participatory governance hoping to enhance the management of the boards and organizations of other villages in B county through a demonstration of the social organization S.

The Train of Thought for Research

We made a comparative analysis of two cases in which the two county governments took the initiative to adopt participatory governance to explore the factors and practical mechanisms used by a basic-level government as it carries out empowerment in participatory governance. The two projects were highly comparable. First, their surroundings were basically the same. The two counties are under the same geographical conditions dominated by high mountains and semi-high mountains and have largely the same culture. The income of villagers mainly depends on migrant work, and the local economies also have a similar structure, mainly based on crop growth and husbandry.

Second, the two projects also display a certain similarity. First, they were both the management projects of input resources dominated by the countylevel, involving the interests of all the communities, and implemented through participatory governance. Second, they have temporal proximity. The Community Development Fund Project in A county officially began in 2010, while the collective forest management project in B county started in 2011. The two projects were faced with largely the same environment, and both were still in normal operation. Third, they have the same operating mechanism. As can be seen from Figure 1, the two projects have the basic operating mechanism that the countylevel governments actively use it to carry out empowerment, delegate management authority and resources, and guiding and encouraging communities to establish self-organization for project management. The governments bring in social organizations to provide technical services, to enhance the communities’ awareness and ability to participate. Both projects have their own relatively complex system of implementation, management, and supervision. The similarity in the regional environment and operational mechanisms of these two projects lays a foundation for their comparability.

Figure 1. Project preparation mechanism

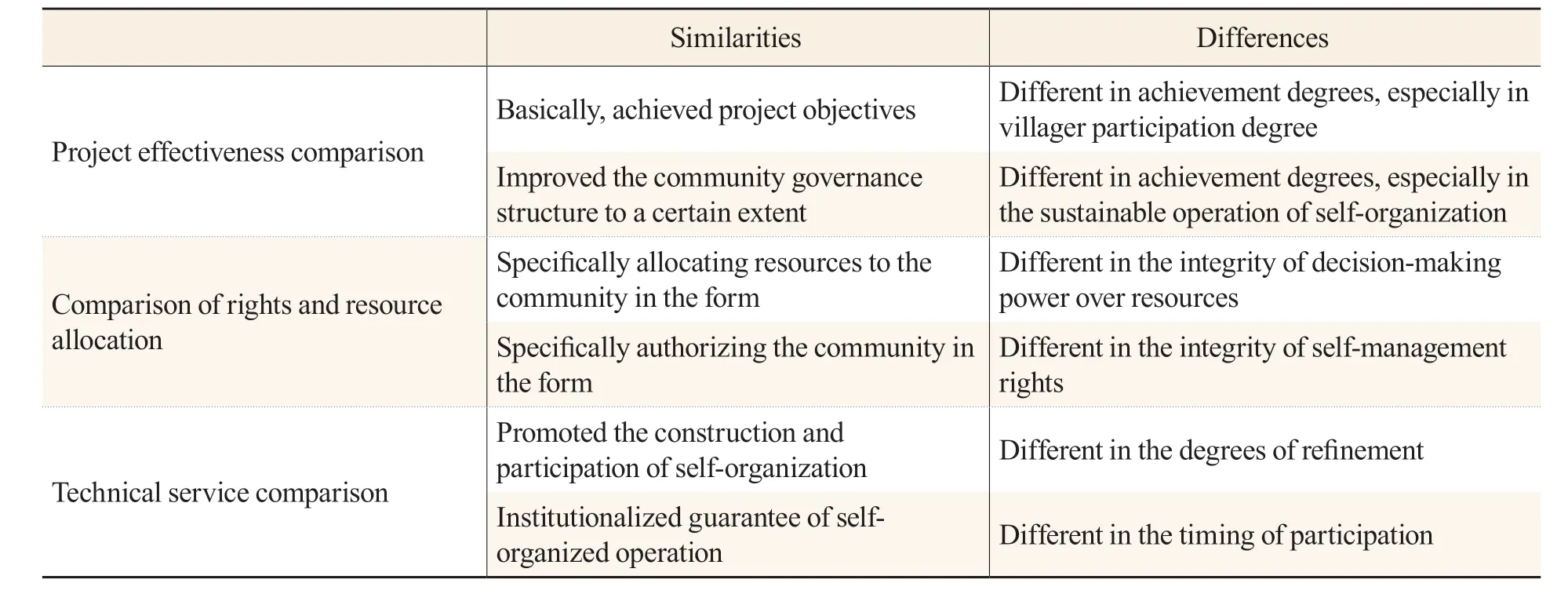

Based on the comparability of the two cases, we developed the following analytical thinking. First, as is shown in comparison, both participatory governance projects with the empowerment that the two basic-level governments took the initiative to carry out (Table 1) have basically achieved their project objectives, but there are differences in the degree of villager participation and the sustainable operation of self-organization. Through further analyses of the source of such differences, we found that these differences come from the degrees of empowerment, i.e., the degrees of the supply of rights and resources and the degrees of refining of technical services despite the similarities between the two projects in terms of their operational modes and structures, and that these factors are probably the key reasons for the differences behind the levels of participatory governance. Therefore, we will present our detailed comparative study of these three dimensions, and finally, through a comparative analysis of these two cases, we will summarize the basic conditions and practical mechanisms of full empowerment in community participatory governance.

Table 1 Comparison of the A County Community Development Fund Project and the B county Collective Forest Management Board Project

A Comparison of Practical Effects

The two participatory governance took the initiative to conduct top-down empowerment, and have achieved some positive results in community governance, but there are also some disparities.

The Positive Results of the Projects

From the perspective of project operation, the two projects have lasted for 10 years, and are still running normally today. They have achieved positive results.

First, both have reached their project objectives and facilitated the coordination between resources and demands. The community development fund project in A county aims to improve the use efficiency of poverty alleviation funds through the operation of community funds, alleviate the community residents’ problems of inadequate production funds and difficulties in borrowing money, and at the same time strengthen the independent management abilities of villages in poverty. From the perspective of project operations, the development fund operations of twenty-five communities in A county have served farming households more than 4,700 times in the past 10 years, responding to the actual needs of villagers. Villagers in L village express that these small loans from the community development fund are useful in solving pressing needs such as the schooling of children and the illness of family members, and their life problems in purchasing agricultural materials and making a livelihood. The twenty-five community development funds have been in operation for ten years, which is evidence that these communities are capable of independent management.

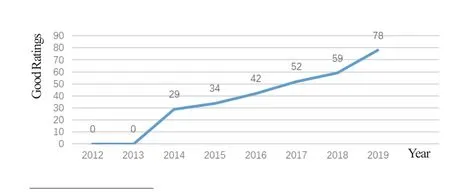

The operational goal of the Collective Forest Management Board in B county is to support community collective protection actions and improve the effectiveness of collective forest conservation. Figure 2 presents the ratings of the eighty-eight boards in B county concerning collective forest protection which reveal an upward trend in the number of communities with good ratings, in a protective direction.

Figure 2. Chart of changes in the number of good ratings obtained by the community collective forest protection boards in B county (2012-2019)

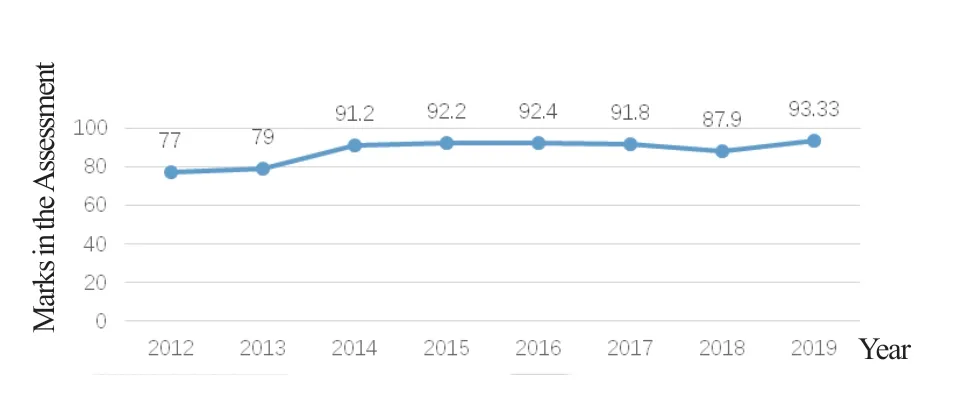

Figure 3. Chart of changes in the assessment of collective forest Management in X Village (2012-2019)

X village has improved its protection effects with the help of social organizations by means of a collective forest management plan and action adjustments. As shown in Figure 3, this village has gradually improved its performance in collective forest management and protection from unqualified to qualified since 2014.

Second, the community governance structure has been improved. First, a new organizational relationship was formed. Referring to Figure 1, both projects have embedded new self-organizations into their original community governance structures. With all the rural villagers’ committees retaining their core positions, the two village committees (CPC village branch committee and rural villagers’ committees) of each village and self-organizations have empowering-empowered and supervising-supervised relationships. This increased the likelihood of refined project execution. By clarifying the boundaries of both the rural villagers’ committee and a self-organization’s rights and resources, they have become a benign management increase without weakening the original governance structure. In this way, they play a positive role in the management of public affairs, improve the governance efficiency of single public affairs, and bring more satisfaction to the villagers. The new management structure not only ensures the authority of the rural villagers’ committees but also improves the villagers self governance.

Difference in the Degrees of Villagers’ Participation

In the two projects, villagers’ participation is both an important means and an important goal of project implementation. Since the implementation of these projects, the participation of villagers has improved, but there is a disparity between the degrees of villagers’ participation in the projects.

The participation in decision-making in L village. As discovered in the field interviews in L village, the villagers attend community meetings and take part in the making of the rules for community development funds, play a part in the operation of the community development funds by means of loans or guarantees, and are basically informed of the core operational rules of the community development funds such as the timeline of loans, the exquisite guarantors, and the overdue payment when an expiring loan is not paid back.

According to the director of the poverty alleviation office, relevant publicity has informed the villagers that “the mutual aid funds are for everyone, each villager has been entitled, and every household has its quota.”①Quoted from an interview with the former director of the A County Poverty Alleviation Office in December 2019.Now that the villagers in L village have participated widely in the establishment and operation of their community development funds, the field random interviews in L village show that the villagers from this village have been relatively well informed of the core operational rules of the community development funds, including the timeline of loans, the exquisite guarantors, and the overdue payment when an expiring loan is not paid back.

The villagers are clear that there are individual quotas in the community funds; they are active in taking part in the establishment of rules, the issuance of and supervision over fund loans, and participate in the project operation in various degrees. That improves the villagers’ recognition of the operation of the community funds and can be classified as decision-making participation, which is important for the sustainable operation of the project.

Expressive participation in X village. The publicity, initiation, and establishment of the collective forest management board project in B county were given high priority. The Forestry Bureau planned in the middle of June 2011 to start the work of the board and in the middle of July required the communities in each village to set up their board of directors and submit a draft of its regulations. Because of such haste, each village formulates its own village management regulations by referring to the charter and time arrangement of the collective forest in B county, and the villagers who participate in the village-level collective forest management board of directors of the local election, management system design, and management work is not much. The participation in the boards in charge of collective forests in B county is more of an expressive participation with expressive empowerment (Fang & Xu , 2015).

Differences in the Sustainable Operation of Self-Organizations

The operation of self-organizations in each of the two projects has a decisive impact on the sustainability of that project, while the factors behind the sustainability of self-organizations themselves come from both the external and the internal. In particular, the external factors are the attitudes of higher authorities and the support system, and the internal ones include the ability of self-organizations to perform independent management and its independent use of resources.

The sustainable operation of community development funds in A county. From the perspective of the internal environment, the management of community development funds in A county and the use of their resources are in a good state, and the self-organizations there operate independently under the supervision of the rural villagers’ committees and have strong independent management. Take L village as an example. The council and supervisory board were elected through a community assembly, and the basic rules of community fund operation were formulated on their own. The council chairperson E believes that the smooth operation of the community development fund was related to the development of the villagers’ assembly, for the villagers themselves attended the assembly to elect management personnel and make the rules. The secured loan system was also designed by the fund council in accordance with the average quota of community funds among alL villagers. In particular, one household without guarantee can borrow 2,000yuan, one household with a three-household guarantee can borrow 5,000yuan, and one household with a six-household guarantee can borrow 10,000yuan. This operational system has been accepted by the villagers and has ensured the sound operation of the community development fund.

L village moderately amended its rules along with the operation of its community development fund. This village has good transport thanks to its location close to the county seat and at first adopted the policy of immediate loans for any application with respect to its community development funds. After a few years of operation, however, it was found that this had caused too heavy a workload to accountants and cashiers. After a consultation by the villagers’ assembly, the lending rule was changed to twice a year, with loans concentrated to free accountants and cashiers from the heavy workload. L village has a strong sense of independent management in its operation of community development funds, including the formulation and appropriate adjustment of rules, while taking into account the fairness, transparency and adaptability of the system and its implementation.

With respect to the use of resources, in reference to the implementation rules of the community development funds of A county, “the community development fund is the common asset of all villagers, over which the villagers’ assembly has the final decision-making power.” Self-organizations are entitled to use funds independently, and the villagers continue to benefit from the community development funds. As a result, this form of microcredit is accepted among the villagers, and its operation has remained within the range of safety.

Second, in terms of the surroundings, several government departments in A county have been aiding the operation of the community development fund. The A county Poverty Alleviation Office is the competent agency of the fund, the Civil Affairs Bureau takes charge of the regular audit and inspection of the fund, the County Agricultural Economic Service Center checks regularly and irregularly the account records and financial public notices, and the Rural Credit Cooperative assists the circulation of the funds. The continuous support from external systems has ensured the safety of the operating environment. From internal and external conditions, the operation of community development funds is sustainable.

Comparatively speaking, the B county Collective Forest Management Boards are faced with relatively complex internal and external environments. First, in terms of their internal environment, the practice of having the same personnel in two organizations, namely the boards and the two village committees, has become increasingly common within the territory of the county. Consequently, the boards of directors were gradually merged into the organizational system of the two village committees and lost their independence. Moreover, they are poor in independent management. For collective forest management, for example, a board of directors should hold a general assembly of shareholders to elect village patrol guards to carry out protection work in accordance with established procedures. However, the first batch of patrol guards in X village was not elected by the general assembly of shareholders. Some of the patrol guards were villagers working outside the village for a long time and failed to perform their management and protection duties, which caused a loss of points in the assessment at the end of the year. This was one of the reasons that X village failed to pass the 2012-2013 assessment of collective forest protection. One of the important objectives of the collective forest management board is to facilitate the village as a community to fulfill the responsibility of collective forest protection, but the board did not develop the acuity of independent management. With respect to the use of resources, the public funds set aside from the forest eco-compensation have a strictly confined scope and can only be used for collective forest protection. In 2015, the entire county accumulated its set-aside amounts of collective forest funds up to more than 10 millionyuan. Moreover, the financial system of “village finance managed by the township government” created a complicated procedure for the use of resources, and many villages didn’t know how to use those set-aside funds.

In terms of the external environment, the government of County B supports the county Forestry Bureau to set aside part (10 percent-20 percent) of the compensation fund as the public fund of the village collective, which is managed by the collective forest management board of the community in each village. However, higher forestry authorities want to distribute all the compensation funds to households, fearing that the funds will not be safe, so the B county forestry bureau is very cautious about using public funds.

Both projects have achieved their goals on the condition that the basic-level governments take the initiative to carry out empowerment, but there are gaps in terms of the participation by villagers and the sustainable operation of self-organizations. As mentioned above, under the circumstance that the two projects are similar in both the external environment and structural design, rights and resources as the main supply factors of the empowerment by basic-level governments and technical services as the supply factor of social organizations are worth further discussion.

Comparison Between the Supply of Rights, Resources, and Technical Services

The two county-level governments as suppliers of rights and resources set up platforms for community participation through explicit empowerment. They strengthen the motivation for community participation by injecting capital and physical resources into communities, and enhanced community participation by introducing technical empowerment. Community governance has been improved through the empowerment of the local government’s initiatives, but the degrees of rights, resource empowerment, and technical services affect the effectiveness of community governance.

Supply of Rights, Resources, and Techniques

In terms of empowerment, both projects have empowerment from the county-level governments, and the rights and resources are clearly assigned to villages. Meanwhile, technical services from social organizations are introduced for technical empowerment.

Clear empowerment to villages: build a platform for community participation.

Both counties have taken the initiative to delegate power to communities. In the A county community development fund projects, the councils and supervisory boards are elected through villagers’ assemblies. The councils consult with the villagers to devise methods for the management and supervision of funds, and at the same time accept the external supervision of the villagers’ assemblies, rural villagers’ committees, township or town governments, poverty alleviation offices, and social organizations. These community development fund councils as new self-organizations are real exercisers of the rights in question.

The B county Forestry Bureau also delegates rights and responsibilities to the village-level councils through various documents. Through supporting documents, the bureau makes it clear that the boards have the right to operate and manage the shares of both forestland and forests, and empowers leaders of innovation by seeing that they have more human, financial, and material resources, as well as the set-aside funds for public uses, at their disposal, and at the same time undertake the corresponding management and protection obligations. According to the agreement, the boards of directors are community self-organizations with certain resources and authority and are empowered with independent operation.

Clear resources to villages: enhancing the motivation for community participation.

Both county governments have made it clear that the resources will be allocated to villages. The A county government decided to distribute funds to villages after some discussion and agreement among various departments but stipulated that the development funds within a community would be for mutual assistance. As a result, the resources after allocations, were moved to the communities under clear private ownership in the archive, with the clear requirement that they are managed by a community fund council to avoid the equal sharing of funds within the community. That frees relevant departments from the concerns about ownership and fund security and empowers communities in terms of resources by making it clear that the community has the ownership and usage rights of the funds.

The Forestry Bureau of B county also designed a similar management system for the collective forest management board stipulating that a community set aside 10 percent-20 percent of collective forest compensation funds to support the public management and protection of collective forests, and that such set-aside funds for public uses can be used for payments to the patrol guards or as the public expenditures for the maintenance of related supporting facilities. Moreover, it has formulated supporting systems concerning supervision, reward, and punishment, and makes it clear that the board of directors is responsible for the management and protection of collective forests.

Introducing technical empowerment with social organizations: enhancing the ability of community participation.

Both county governments are active in bringing in social organizations to provide technical services. A county introduced the G Community Development Center which helps build the implementation frameworks for community development funds and formulate detailed rules for the implementation of community development funds to support the entire project. B county introduced social organization S to carry out a pilot test in X village, to demonstrate the management of village-level collective forests, improve board management systems, and enhance the efficiency of collective forest management and protection. Both social organizations have provided technical services such as the spread of information, the improvement of community governance structures, assistance in institutionalization, and supervision over the operation of self-organizations.

Differences in Government Empowerment

The two county-level governments show differences in the integrity of their empowerment and the degrees of refinement of technical services although both carry out the empowerment of rights, resources, and technical empowerment.

Differences in the integrity of independent management rights.

Differences in the status of legal persons of self-organizations.

The community development funds in A county have been registered as a specialized cooperative. This identity provides strong support for the later work of the community development funds, including the registration of business accounts and the independent management within a community. According to A county’s community development fund implementation rules, the County Civil Affairs Bureau is responsible for the registration of community development funds, including the perfection of registration information and the examination of registration qualifications. According to the poverty alleviation office at that time, the former director had even traveled to the city to purchase special paper for registration because the county Civil Affairs Bureau was in lack of it. The registration of the community development funds as legal persons was supported by the departments of the A county government and individuals, which ensures access to their independent identities.

The collective forest management boards in B county are not registered as legal persons and therefore lack legal independence. Various government departments worked together to provide technical support for the communities to set up the boards in question. The Civil Affairs Bureau of B county did not help the boards of directors to register themselves, although it did support their establishment and operation. Consequently, the communities cannot apply for a business account and must borrow through the financial accounts of the two village committees. As a result, the boards of directors lack the identity of legal persons which is an important support in the management of collective forests although they are nominally independent organizations, and the resources are accordingly managed by the two village committees. Therefore, the boards of directors are self-organizations that have not been fully empowered.

Differences in the independence of self-organizations’ management. These differences are mainly seen in the independence of self-organizations and the effectiveness of the system. In A county, the G Community Development Center holds that the community development fund must have its independent management organization, which shall be managed by trusted members elected by residents of the community. At the same time, considering the authority of the two village committees, the staff of the G Community Development Center explained the relationship between the community development funds and the two village committees, saying that the two village committees are both empowers and supervisors, while the community development funds are the empowerees and supervisees. The clarifying of the relationship of these two guarantees certain independence of the self-organizations and the embedding of the original management system.

In terms of supporting systems, the community development fund systems in A county are independently formulated by villagers. Take L village as an example. The formulation of their system has gone through a long process. In the first step, L village arranged the members of the rural villagers’ committee to receive the training for the project of community development funding, so that they could clearly understand the background and future operation of such projects. In the second step, the members of the rural villagers’ committee of L village and the staff of the G Community Development Center did project promotion and mobilized the residents within the community, so that every household could be well informed of the project. In the third step, the members of the rural villagers’ committee collected votes among four groups after the dissemination of relevant information to elect the community fund management team. In the fourth step, the management team convened the rural villagers’ committee to discuss and determine the management methods of the community development fund. Usually, these systems are preliminarily designed by the management team members and then improved by the community assembly. The two village committees, members of self-organizations, and villagers within the community all had a clear understanding of the community development fund and participated in the planning of the system. Due to openness and transparency in the designing process, the system is highly acceptable among the villagers, and its operation has also been recognized by different interest groups in the community. This has thus maintained the effectiveness of the system.

The boards of directors of collective forests in B county were designed to have a similar orientation as that in A county. They are independent organizations under the leadership of the two village committees and manage and protect collective forests. However, as mentioned above, because the boards of directors in B county lacked legal independence, the membership of the committees highly overlapped, and the self-organizations gradually integrated into the rural villagers’ committee and thus lost their independence. As for the devising of the system, at the same time, the members of the boards did not carry out extensive publicity because they had to make a haste in submitting the regulations of the village collective forest management board within a short month as prescribed. As a result, the villagers’ understanding of this system is not high, and its implementation effectiveness is lacking, and the implementation is thus inefficient.

Differences in the integrity of decision-making power over resources.

Differences in the mode of resource management. The community fund resources in A county are managed by self-organizations. The procedure starts with the registration of such community funds as specialized cooperative organizations in the Civil Affairs Bureau. Then, business accounts are opened in the rural credit cooperatives, and the resources are officially allocated to each community after the Finance Bureau allocates funds to these accounts. In reference to the A county Community Development Fund Implementation Rules, “The community development funds are the common assets of all the villagers, and the villagers’ assembly has the final decision-making power over the funds in question.” The councils are elected executive bodies responsible for the management of community development funds. The two village committees, county- and township-level government departments, and external social organizations are all assisting and supervising institutions, and do not interfere in the resource management within communities.

In B county, forest eco-compensation funds, like other funds in the village, are “village finance managed by the township governance.” Because the boards of directors are not registered in the Civil Affairs Bureau, and thus cannot open an independent business account of set-aside public funds, the payment accounts of such funds are all opened under the accounts of the rural villagers’ committees. Collective funds are allocated to the accounts of the two village committees by the County Finance Bureau, and individual funds to the accounts of farming households by the same bureau.

Differences in the decisions about the use of resources. In A county, the use of community funds after their allocation to a community is confined to “production, or contingent or temporary expenditures, rather than non-productive consumption.” The borrowing and lending of funds within this scope are managed by the community fund councils and receive external supervision. No other higher-level departments interfere with such community funds.

The set-aside amounts of forest eco-compensation funds in B county are also confined in terms of their use. According to the measures in the province, compensation funds should fully be distributed to households, so the setting-aside of public funds in B county is something innovative, but the use of such set-aside funds is strictly confined and has to be pertinent with the management and protection of collective forests. For example, X village sets aside 10 percent of its collective forest funds, which can only be used as subsidies for the patrol guards instead of other public affairs in the village. Moreover, if it must be done through the accounts of the rural villagers’ committee, and any remaining funds will be stockpiled because the boards of directors do not know how to use them.

Differences in the technical services of social organizations.

The differences in technical supplies in these two projects are also an influential variable in their operation.

Different degrees of refinement.

The G Community Development Center arranges its work within the community in as detailed a way as possible, providing accompanying services. Take the informative promotion as an example. The G Community Development Center first offered the training of village cadres, training them to disseminate information and do mobilization in the community. Then, it carried out return visits within the community, to ascertain to what degree the villagers had really been informed of the community development fund. It did so to help the villagers understand the source, intentions, and basic principles of project funding. The refined dissemination of information alleviates the problem of information asymmetry in community governance.

After the commencement of a community development fund, the community is accompanied as it goes through at least one cycle of operation, to provide support for the solutions of unexpected problems in the operational process. For example, after a village started the trial operation of its first round of loans, a mother and her daughter came to get loans by guaranteeing for each other. Other villagers protested that they were relatives who were not qualified for mutual guarantee, but the mother and daughter argued that the management measures proposed that father and son could not mutually guarantee the loans but did not explicitly say that mother and daughter could not do it either. Because of this unexpected occurrence, the village had to stop all loan activities, withdraw the money already lent, and state more detailed management rules, articulating that mother and daughter cannot mutually guarantee a loan. The community fund re-started after that.

In B county, social organization S did not conduct any large-scale publicity within the community, nor did it confirm the degree of the villagers’ knowledge about the collective forest management board. The regulations were improved mainly through the discussion among the villagers representatives, with the first draft discussed and approved by the community assembly. However, due to the scattered distribution of X village, many villagers were living away from hometowns as migrant workers, and fewer attend the villagers’ assembly. Accordingly, neither the access to information nor the expression of attitudes of those who were absent had been considered in the revision of the regulations. Moreover, in the projects run by the boards of directors in B county, the social organization S participated in them in only a limited way. It had in-depth participation in one single community, offering limited technical support in other communities. Furthermore, it made no breakthrough in the cooperation with the communities or the government, or in the system design, or in the skills of community implementation.

Different timing of intervention services.

As the A county government took the initiative to invite the G Community Development Center to participate in the implementation of the community development fund projects, the G Community Development Center took part in the top design of those projects. The Center reached an important consensus with respect to crucial questions including the ownership and management of project resources and joined the formulation of the A county Community Development Fund Implementation Rules. These rules specifically delineate the use of the funds, affirming that the communities enjoy the rights to the ownership and management of the resources, and that government departments shall be oriented toward service support, thus laying the foundation for the development of community work in the later period.

In the case of the collective forest management projects in B county, social organization S’s technical services were embodied in assisting communities to improve their internal management and technical support for collective forest management, such as the planning of the collective forest management and the development of the collective economy. Social organization S also offered support to the business training of the boards throughout the county.

The impact of empowerment differences.

The differences in the full supply of resources and rights and in the refinement of technical services brought multi-dimensional influences to the operation of the projects.

The Degree of completeness of empowerment affects the initiative of community participation.

A county completely empowers the ownership of the funds, as well as the responsibility of management. The training of the members of the management teams for the community funds in 2009 emphasized that the government has the right to take its empowerment back where a certain community fund is badly managed. The managers were under pressure, and there was a widespread “fear that the loan would fail to be repaid.” Due to the empowerment of resources and rights, the managing members changed their positions, and gained a mode of thinking as leading roles, considering how to use the funds well and ensure their safety. Accordingly, some guaranteeing systems were designed. The guaranteeing system further delegated the responsibility of managers to the villagers, who had to find other farming households as guarantors before being approved for loans. The households as guarantors would be obliged to pay back the money if the debtors failed to repay the loans. That is based on the fact that rural communities are traditionally a “relationship-oriented society,” embedding the borrowing and lending into the community networks to guard against the risk of “bad debts.”

The complete empowerment of resource ownership also ensured that villagers can benefit from it. Many farming households in L village chose to wait and see at first. In this village, a villager who borrows money from the community development fund must pay a membership fee of 20yuanto become a member, but many villagers did not pay the membership fee. Seeing that other villagers benefited from the fund, and that the management of it was transparent and standard, they gradually changed their wait-and-see or suspicious attitudes, applying for membership and joining the fund operation.

In B county, a board of directors does not have the status of a legal person, and the funds are also held in trust under the accounts of the two village committees, so it does not have the full right to use the funds, and that lead to the failure of completely delegating the responsibility. In accordance with regulations, the set-aside public funds cannot be used for expenses other than patrol guards’ subsidies and services related to collective forest protection. For example, it cannot be used for subsidies for managerial personnel. For the part of the Forestry Bureau and the two village committees, they tacitly accepted that salaried people in the government system should assume the management of the boards of directors now that they cannot provide corresponding subsidies to the managers.

The villagers did not think there was a high correlation between the set-aside amounts of eco-forest compensation funds and their own interests. But in fact, the setting aside of public funds reduces the compensation for individual households. Often, villagers take a hesitant attitude towards the boards that have neither an independent identity nor the qualification to enjoy their setting aside of public funds.

The degree of refinement of technical services affects the community capabilities for participation and management.

First, the degree of the refinement of technical services affects the community selforganizations’ capabilities for management. Take the guaranteeing system as an example, which is a basic plan that the G Community Development Center worked out after its consultation with the leaders of all related departments at the consultive meeting of A county. “At the county-level consultive meeting, some people wondered what to do if a debtor refused to repay the loan. One of those who attended the meeting came up with an idea. That was, the loan must be guaranteed by five, or a certain number of, households before being approved. If the debtor fails to repay the loan, those households will be involved.”①Quoted from the interview with the former director of the A county Poverty Alleviation Office in September 2019.

In the training of the villager cadres and village management teams, the G Community Development Center instructed them to think about how to attract borrowers and at the same time convince the villagers of the managerial personnel’s proposals. The managerial personnel further considered system designs from the perspective of fairness and justice, which was a technique-inspiring process. In the process of technical training, the community gradually formed the capability for self-management, and through the accumulation of habits, the community has been encouraged to form a self-management mechanism, maintaining the operation of community development funds.

Second, the level of technical services affects individual villagers’ capability for participation. The G Community Development Center has enhanced the villagers’ participation through refined technical services. Take L village as an example. At the beginning of its community development fund project, L village helped the villagers learn about the project by means of several rounds of promotion. Then, the villagers elected the team for community fund management, which convenes the villagers’ assembly to discuss and negotiate the management methods of the community development fund, and in the end, the community assembly voted on the methods for the management of the community development fund. Several rounds of participation encouragement have made sure that the villagers can express their intentions at the community assembly under the condition of being well informed. The villagers’ rights to know and participate are ensured. At the same time, the community assembly adopted the methods the villagers used to vote, for example, to vote with beans to avoid the conflict in the village caused by a show of hands. That improves the villagers’ ability to deal with negotiation scenarios.

In contrast, the collective economy within the community of X village, B county, declined soon after the withdrawal of social organization S. Thus, the situation of overlapping memberships of the board of directors and the two village committees remains unimproved, and the board of directors did not develop the capability for self-management.

The interaction of multiple actors affects the coordination of empowerment.

The implementation of both projects involved the participation of multiple stakeholders, including multiple county government departments, social organizations, two village committees within the communities, self-organizations, and villagers. In the operation of A county community development funds, the A county government set up a leading team involving multiple departments, and reached an empowerment framework within which a consensus was reached through internal consultation. The stakeholders within the community, including the two village committees, self-organizations, and villagers formed an internally recognized operational framework for the community development fund through consultation. The G Community Development Center, as a third party, facilitates the communications between basic-level governments and communities, participates in the framework design of the empowerment of basic-level governments, and provides external environment guarantees for the operation of community development funds. It helps the community to form a highly recognized operation system promoting the coordinated empowerment between the countylevel government and the communities.

The leading team of B county first reached an agreement on the basic framework of empowerment but failed to achieve a consensus about supporting measures. The multiple actors within the community have arrived at an agreement on the framework of empowerment, but the management of self-organizations is not elaborately designed. Social organization S failed to manage the coordinated empowerment between the county government and the communities. This is largely related to that social organization S has missed the top-level design and the low degree of refinement of community technical services.

Summary

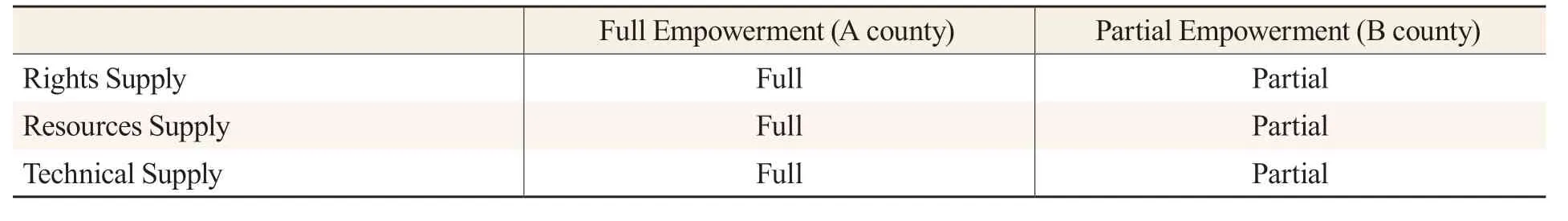

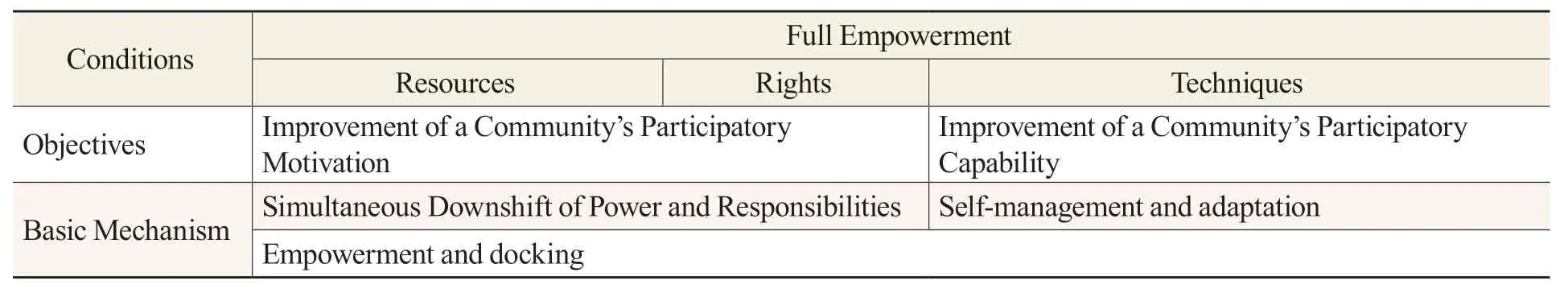

Our analysis has provided numerous examples of county-level governments’ adopting participatory governance. From this analysis, it is clear that active empowerment can improve community governance, and the empowered contents involve rights, resources, and technical services. As was shown by the comparative analysis of the various cases, the degree of empowerment is a key factor in determining whether a basic-level government can improve community governance through participatory governance. As shown in Table 4, full empowerment means that the government undertaking the participatory governance of community public affairs endows the public with complete rights and resources from top to bottom, and at the same time provides refined services required for effective governance to facilitate the effective improvement of community governance. The term “rights” here refers to the self-governance right of community self-organization, whose core characteristic is the identity of the organization and the independence of management. The term “resources” refers to the funds or materials provided by the government from top to bottom, whose core is the decision-making power concerning resource allocation. The term “refined services” refers to the corresponding training and support concerning the participation, organization, management, and other skills provided externally in the practice of community self-governance, whose core is to assist the internal enhancement of the community. All of these are necessary to enhance communities’ motivation and the ability to participate by means of full empowerment and to ultimately achieve effective community governance.

Table 4 Types of Empowerment

Insufficient community participation exists in rural community governance, and one of the important reasons is inadequate motivation. The full empowerment of resources and rights helps a community gain a sense of belongingness in terms of resources, enhances the motivation for community participation, and stimulates community participation. The full empowerment can break the conventional resource management structures and put into practice new rules widely accepted by villagers. In the case of partial empowerment, however, things may fall into the Tacitus trap, and villagers can thus choose the tactic of idle observation. Another reason for insufficient participation is an inadequate capacity for participation. Refined technical services can facilitate a community to improve its capabilities for participation in the process of participation, develop its capabilities for independent management, and encourage the independent operation of self-organizations to improve community governance.

Conclusion and Discussion: Full Empowerment and Its Practical Mechanisms

Based on this case study, we propose the concept of full empowerment, and put forward the fact that full empowerment has an important, positive impact on the practice of effective community governance. The mechanism of its influence is summarized as follows.

First, full empowerment is helpful for a community’s ability to undertake its responsibility, and these two aspects constitute the entire mechanism for the concurrent delegation of rights and responsibilities. As mentioned above, both projects promoted the delegation of resources and management, and the coordination of community rights and responsibilities. The difference is that the complete delegation of rights is more conducive to the villagers’ accepting the delegated responsibilities. That was conducive to improving management awareness within the community. The villagers become aware that when the resources are useful and available, they are willing to undertake the responsibilities, and design a corresponding management system to ensure the effective management of resources.

Second, refined technical services are conducive to the formation of self-management and adaptation mechanisms in a community. Refined services are helpful for creating a good internal and external environment for the community, assisting the community to re-organize itself to form a new community management structure and management path, improving the capabilities of both organizations and individuals for participation and management, developing a mechanism for self-management and adjustments, and maintaining the sustainable operation of community self-organizations.

Third, multi-actor interactions are conducive to the coordinating mechanisms of empowerment. Cooperation based on multi-level consultations among government departments, social organizations, and communities are conducive to building a framework for empowerment and assisting the basic-level government to provide full empowerment within a safe scope. The community can thus form a stable and safe management system to ensure an effective and safe transition to self-management through local empowerment. The participation of multiple actors and technical support and coordination is helpful for the coordination and balance between the supply of government resources and the needs of communities.

Full empowerment is the condition for the realization of participatory governance, and its practical mechanisms include the simultaneous delegation of power and responsibility through the operation of empowerment, both the mechanism for community self-management and adjustments and the mechanisms for the coordination of empowerment achieve the goal of enhancing a community’s motivation and capability for participation. The conditions and mechanisms are shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Conditions and Mechanisms of Participatory Governance Operation

Participatory governance promotes interactions between the state and society through the process of participation. As this research shows, in community governance led by the state, a basic-level government that is willing to take the initiative to carry out empowerment can dominate the process of empowerment, control the risk of empowerment, improve the efficiency of the use of resources, and improve the effectiveness of community governance, thus creating a win-win situation.

Full empowerment as proposed in this paper has a certain explanatory significance for the effective practice of participatory governance, but the practice of participatory governance also involves other factors, such as local cultural backgrounds, governance traditions, and local elites. Many factors can join together to form an influential network and may affect the process and mechanisms of empowerment. We suggest that future studies of the effective practices of participatory governance can include other variables, including social capital, and actors such as township governments. Such considerations could build a more complete framework for interpretation by including more measurements of villagers’ attitudes that could better explain the influence of full empowerment on the practice of community governance from multiple dimensions. The cases in this paper are based on the comparisons of two communities. The practice of empowerment in other areas may have different logic and practice fields, so this paper is only a preliminary discussion.

杂志排行

Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- Determination of Relationships and Allocation of Responsibilities—Taking the Adjudication of Household Service Contract Disputes as an Example

- A Brief Analysis of Competitive Sports Depicted on the Portrait Bricks and Stones of the Han Dynasty

- Tri-Engine Structure and Industrial Composition of Cultural Productivity

- Measurement and Spatial Difference Analysis of Innovation-Driven Urban Development Levels in Sichuan Province

- Stock Market Turnover and China’s Real Estate Market Price: An Empirical Study Based on VAR

- Research on the Impact of the Pension Insurance System on the Optimization of the Consumption Structure of Rural Families