A soy glycinin derived octapeptide protects against MCD diet induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice

2022-07-11PengMaRongrongHuangYuOu

Peng Ma, Rongrong Huang, Yu Ou*

School of Life Science and Technology, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China

ABSTRACT

Soy glycinin derived octapeptide (SGP8) is a peptide obtained from degradation of the soy glycinin, whose amino acid sequence is IAVPGEVA. To determine the effect of SGP8 on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),steatosis HepG2 cells were induced by 1 mmol/L free fatty acid (FFA) and C57BL/6J mice were fed with methionine-choline deficient (MCD) diet for 3 weeks to establish NAFLD model. The results of oil red O staining and total cholesterol (TC)/triglyceride (TG) contents showed that SGP8 could significantly reduce the lipid content of steatosis HepG2 cells. In vivo, SGP8 lowered plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT)and low density lipoprotein (LDL) content, normalized hepatic superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) production, and reduced the severity of liver in flammation. The results of Western blotting showed that SGP8 increased expression of Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) and phosphorylation level of AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK) in hepatocytes. Through activation of SIRT1/AMPK pathway, SGP8 downregulated the expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) and its target genes ACC and FAS expression levels, and increased the phosphorylation level of acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC).Furthermore, SGP8 also upregulated the expression of transcription factor peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α (PPARα), which was regulated by SIRT1/AMPK pathway, and its target gene CPT1 level. In conclusion, SGP8 might improve NAFLD by activating the SIRT1/AMPK pathway. Our data suggest that SGP8 may act as a novel and potent therapeutic agent against NAFLD.

Keywords:

Soy glycinin derived octapeptide (SGP8)

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

HepG2 cells

Methionine-choline deficient (MCD)

SIRT1/AMPK pathway

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an internationally recognized chronic metabolic disease that refers to extensive liver damage, including steatosis, steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis [1,2]. It has been reported that the prevalence of NAFLD accounts for 33.6%-34.0% in the United States, and the prevalence of NAFLD also accounts for 25%-30% in developed European countries [3]. According to the statistics of population data from Asia,the incidence of NAFLD is between 5% and 40% in Asian countries,among which the prevalence of NAFLD is between 5% and 24% in China due to the different lifestyles of urban and rural population [4,5].Therefore, developing drugs for the treatment of NAFLD is important for NAFLD patients.

Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1), known as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide(NAD)-dependent deacetylase 1, plays a major role in the regulation of AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation [6,7]. AMPK can be activated by increased AMP/ATP ratio. In addition, LKB1 and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-β (CaMKK β)are two recognized key factors to activate AMPK phosphorylation [8].Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT1) is the rate limiting enzyme for controlling entry and oxidation of fatty acids into mitochondria,which is upregulated by transcription factor peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α (PPARα) [9,10]. Acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC)and fatty acid synthetase (FAS) are the rate limiting enzymes in fat synthesis metabolism, which is regulated by the transcription factor sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) [11]. Previous studies have shown that activated AMPK can upregulate PPARα and downregulate SREBP-1c expression [12,13].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a transcription factor known to be involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism and in flammation and has been implicated in regulating gene expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α(TNF-α) [14]. PPARγ could activate stress inflammatory response through the negative interference in the transcriptional repression of genes, including nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) [15]. Macrophage polarization is an important mechanism for regulating the in flammatory response [16].PPARγ activation can also lead to functional polarization of macrophages, which is an important mechanism in regulating in flammatory response [17].

Methionine-choline deficiency (MCD) diet is a common method used to induce non-alcoholic steatohepatitis models [18,19]. The lack of methionine and choline results in the inability of triglycerides to be transported out of hepatocytes in time, and eventually leads to accumulation of lipids in the liver cells [20]. Not only obese people develop into NAFLD, but lean people still suffer from NAFLD [21].The MCD diet model is associated with loss of body weight and are not insulin resistant [22,23]. Studies have shown that lean NAFLD patients have little or no insulin resistant [24].

Bioactive peptides have a regulatory effect on the body [25,26].Due to the advantages of relatively simple synthesis and obvious bioactivity, bioactive peptides have become a research and development hotspot in recent years. 11S globulin is one of the main components of soy protein. The soy glycinin derived octapeptide (SGP8)is a peptide with the amino acid sequence IAVPGEVA, which is obtained after the degradation of 11S globulin [27]. SGP8 can competitively inhibit the activity of hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase (HMG-CoAR), the rate limiting enzyme of cholesterol synthesis, and regulate the metabolism of glucose and cholesterol in cultured hepatocytes [28]. However, SGP8 has not been reported for the prevention and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The purpose of this study is to clarify whether SGP8 could significantly reduce the steatosis of hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo.The mechanism of SGP8 improving NAFLD was also discussed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and reagents

SGP8 (molecular weight: 754.87; amino acid sequence:IAVPGEVA) was synthesized and purified by Sangon Biotech(Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (China). The results of chromatogram and mass spectrometry showed that the purity of SGP8 was 99.137%,and the sequence was IAVPGEVA (Fig. S1). The following materials were used in the present study: Dulbecco modified eagle’s medium (DMEM)-high glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low density lipoprotein (LDL),superoxide dismutase (SOD), and malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kit(Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China), bezafibrate and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)(Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology, China), antibiotics and fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA), isopropanol, oleate, palmitate,oil red O and defatted bovine serum albumin (St Louis, MO, USA),MCD-diet feed (Nantong trophic Technology Co., Ltd., China),TRIzol reagent, RevertAid first strand cDNA synthesis kit,quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay and protease & phosphatase inhibitors cocktail (Thermo Scientific, USA),radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Wanleibio, China),polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore Corporation,Bedford, MA, USA), efficient chemiluminescence (ECL) plus kit (Beyotime, China), antibody to phosphorylated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (pACC), ACC, phosphorylated AMP activated protein kinase (pAMPK) and AMPK (Bioworld Technology, Co., Ltd.China), and the rest of the antibodies (Wanleibio, China).

2.2 Cell culture

HepG2 cells were purchased from Shanghai Institute of cell biology (Shanghai, China) and cultured in DMEM containing 1% antibiotics and 10% FBS in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2at 37 °C. The mixture of oleic acid and palmitic acid (2:1) was dissolved in DMEM containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) under proper heating conditions to prepare free fatty acid (FFA) solution. HepG2 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103cells/well in 96-well plates or 1.25 × 105cells/well in 6-well plates and incubated overnight. Then,HepG2 cells were incubated for 24 h in DMEM containing 1 mmol/L FFA and SGP8. The control group only contained 1% BSA. And then 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, after which the medium was aspirated and 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to dissolve the crystals. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured with an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader (Multiskan Mk3, Finland). The percentage of cell survival was then calculated for each group by normalization of the readings against the absorbance of negative control.

2.3 Oil red O staining

HepG2 cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS).The cells were stained with 0.5% oil red O at 37 °C for 1 h, and then rinsed with 60% isopropanol for 2 min, and photos were taken under the microscope [29,30]. In order to quantify lipid accumulation,200 μL of 100% isopropanol was added to extract oil red O and detect the optical density of the solution at 500 nm [31].

2.4 Animals and diets

The study was approved by China Pharmaceutical University Licensing Committee. The experiment was performed in accordance with approved guidelines. Six-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (18–22 g)were purchased from Animal Center of Yangzhou University. The mice were placed in a room at 22 °C with 12 h of light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. After 1 week of acclimatization, the mice were divided into 4 groups (NCD: normal-diet-fed group; MCD:MCD-diet-fed group; MCD +LSGP8: MCD-diet-fed + intravenous injection 1 mg/(kg·day) SGP8 group; and MCD+HSGP8: MCD-dietfed + intravenous injection 5 mg/(kg·day) SGP8 group. There were 6 mice in each group).

The experiment sustained for 3 weeks. At the end of the study,the food was removed 12 h before the mice were euthanized to avoid affecting the detection of biochemical indicators. The blood was collected by eyeball extraction for the detection of serum biomarkers.Mice were dissected to remove the liver. A portion of liver tissue was put into tissuefixative for histopathological analysis. The remaining liver tissues were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen for the detection of liver TG/TC/MDA/SOD and protein expression analyses.

2.5 Biochemical parameters measurement and histological analysis

Blood biochemistry of alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/LDL was measured using commercial kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China) in the serum samples. Hepatic TG/TC/MDA/SOD contents were measured using commercial kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China). The concentrations of hepatic TG/TC/MDA/SOD were analyzed and normalized by protein concentration. The liver tissue hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)and oil red O staining were entrusted to Nanjing Superbiotech Co., Ltd. (China). Liver tissue was fixed with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Serial 4 μm sections were subjected to H&E staining according to standard procedures.Intrahepatic lipid was visualized using the oil red O staining.

2.6 qPCR

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA was extracted from HepG2 cells using TRIzol reagent. RNA was reverse transcripted to cDNA with Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. The expression of mRNA was quantified using the ABI Quant Studio 3&5 Real-Time PCR Systems with qPCR assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression of the target gene was analyzed by 2-ΔΔCtmethod, andGADPHgene was used as an internal control. The sequence of primers used in the experiments are listed in Table 1 [32].

Table 1Primers used for qPCR.

2.7 Western blot analysis

Liver tissue and HepG2 cells protein were extracted according to the instructions of the radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA)manufacturer. Protein extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electropheresis (SDS-PAGE) and were transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.15% Tween-20) containing 5 g/100 mL nonfat milk powder for 1 h,followed by incubation with anti-SIRT1, anti-AMPK, anti-CPT1,anti-PPARα, anti-SREBP-1c, anti-pAMPK, anti-FAS, anti-PPARγ,anti-β-actin, anti-pACC, anti-ACC, anti-TNF-α or anti-IL-6 antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Next, the membrane was washed 4 times with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase(HRP) binding secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature.The antigen antibody complex band was displayed using ChemiDoc (BIO-RAD, USA) and integrated density analysis was implemented using ImageJ software.

2.8 Statistical analysis

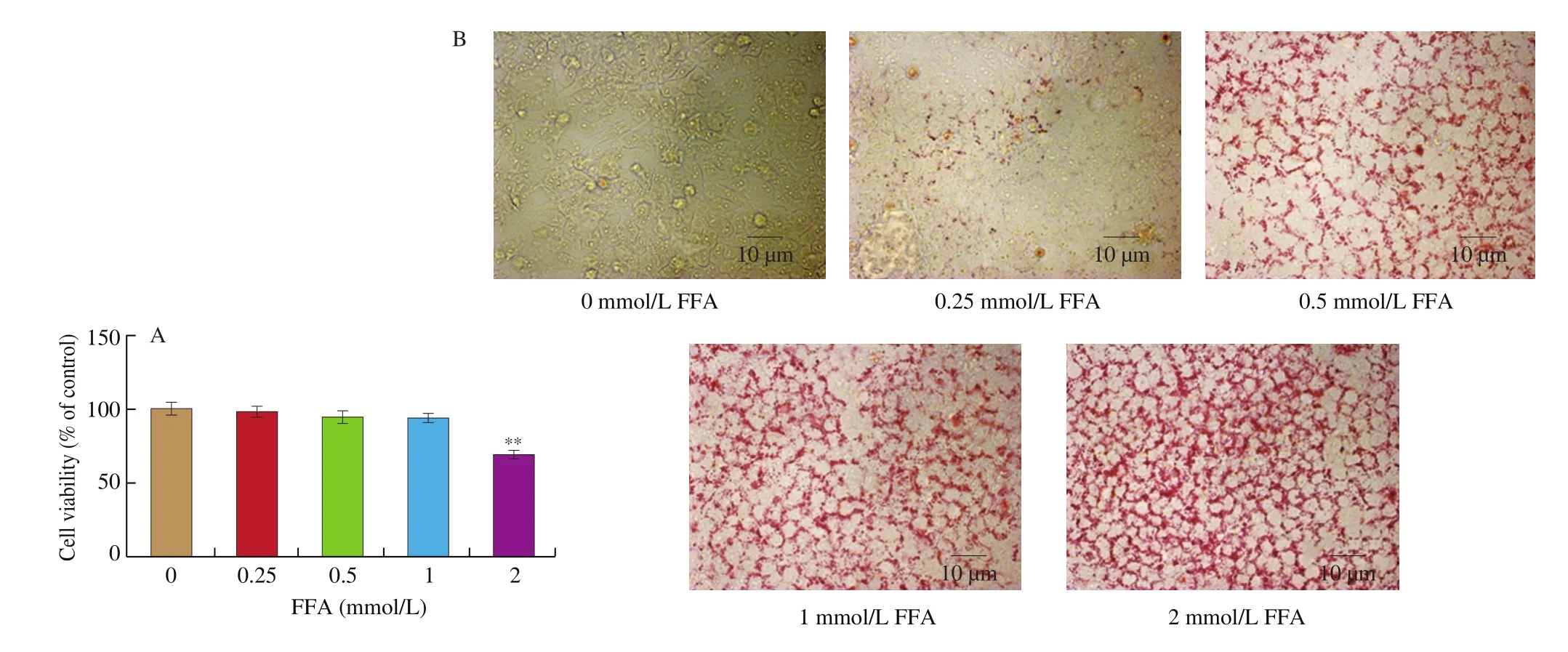

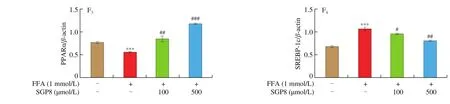

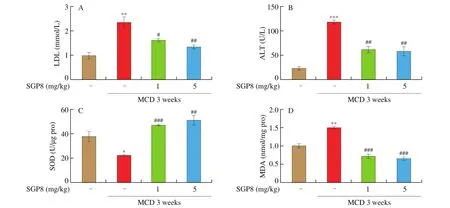

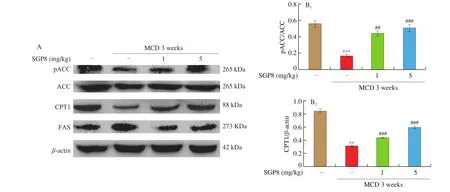

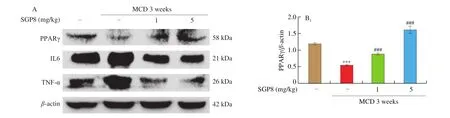

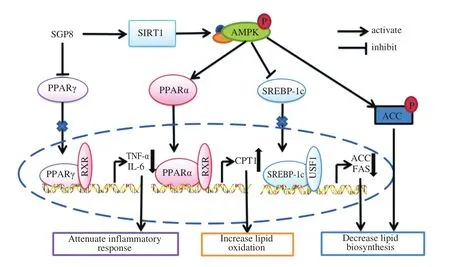

The results were expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5. One-way ANOVA was used to test the significance of the differences among the groups.P> 0.05 was considered as no significant difference and 0.01 Hepatocytes were cultured to a mixture of FFAs for 24 h to investigate the effect of various concentrations of FFA (oleate:palmitate = 2:1) on cell viabilityin vitro[33,34]. The cytotoxicity of FFA on HepG2 cells was measured using an MTT assay. It was found that HepG2 cell viability was not affected by 1 mmol/L FFA, but 2 mmol/L FFA significantly reduced cell survival rate (Fig. 1A). Oil red O staining is an effective method to detect hepatic steatosis [35]. The staining results revealed that 1 mmol/L FFA significantly increased the lipid accumulation compared with the control group in HepG2 cells (Fig. 1B), which could be used as a cell model of hepatic steatosis. To determine the incubation concentration of SGP8, the MTT assay was used to detect the effect of SGP8 on cell viability. The results show that SGP8 has no cytotoxicity below 500 μmol/L (Fig. S2).The oil red O staining indicated that the lipid droplets were significantly reduced in the co-treatment with FFAs and SGP8 group compared to that of the cells given FFA in the absence of SGP8 (Fig. 2A). The photo of oil red O extraction and the detection of optical density (OD500nm) showed the same results (Figs. 2A and B).At the same time, the effects of SGP8 on the contents of TC and TG were also detected. The results indicated that SGP8 could significantly reduce the levels of TG and TC in the HepG2 cells (Figs. 2C and D).Overall, these findings suggest that SGP8 attenuates FFA-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. Fig. 1 FFA-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. (A) Cell viability of HepG2 cells. (B) HepG2 cells were stained with oil red O and viewed under a microscope at 400× magnification. HepG2 cells were incubated in 96-well plates or 6-well plates overnight. Then, HepG2 cells were cultured with FFA (0–2 mmol/L) for 24 h. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **P < 0.01 versus the control group. Fig. 3 SGP8 promotes SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway activation in vitro. (A) mRNA expression levels of FAS and CPT1 in HepG2 cells. (B) mRNA expression levels of SREBP-1c and PPARα in HepG2 cells. (C) Representative Western blot image of pACC, ACC, CPT1, FAS and β-actin. (D) Western blot analysis showing effect of SGP8 on the protein expression levels of CPT1 and FAS and phosphorylation level of ACC. (E) Representative Western blot image of SIRT1, pAMPK, AMPK, PPARα, SREBP-1c and β-actin. (F) Western blot analysis showing effect of SGP8 on protein expression levels of SIRT1, PPARα, and SREBP-1c, and phosphorylation level of AMPK. HepG2 cells were incubated in 6-well plates overnight. Then, HepG2 cells were incubated for 24 h in DMEM containing 1 mmol/L FFA and SGP8. The control group only contained 1% BSA. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus the control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus hepatic steatosis group. Fig. 3 (Continued) In the liver, ACC, FAS, and CPT1 are key enzymes in fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, respectively [36-38]. As shown in Figs. 3A, C and D, the mRNA and protein level of FAS was increased in HepG2 cells. However, the mRNA and protein levels of CPT1 and phosphorylation level of ACC were decreased significantly in hepatic steatosis group compared to control group. When SGP8 was treated,FAS level was downregulated, but CPT1 level and phosphorylation level of ACC were upregulated appreciably compared with the hepatic steatosis group. SREBP-1c and PPARα are important transcription factors in lipid metabolism of hepatocytes [6,39]. The mRNA and protein expression of SREBP-1c was decreased, while PPARα expression level increased significantly when treated with SGP8 in HepG2 cells (Figs. 3B, E and F). In previous reports, SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway played an important role in liver lipid metabolism [6]. So,this study investigated the effects of SGP8 on SIRT1 and AMPK expression in HepG2 cells. SGP8 treatment upregulated the protein expression levels of SIRT1 and pAMPK (Figs. 3E and F). These results indicated SGP8 might promote SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway activation in vitro. In order to research the protective effect of SGP8 on hepatic steatosis in NAFLD mice, liver injury was induced by MCD diet for 3 weeks. As shown in Fig. 4A, the liver of mice fed with MCD diet was paler than that of mice fed with normal diet. In contrast, the liver from co-administration of SGP8 and MCD diets mice was smoother,more complete, more ruddy and softer than those mice fed only with MCD diet. Histological examination of H&E and oil red O staining results revealed that MCD diet could cause obvious macro-vesicular steatosis of liver, however, lipid deposition was improved in the liver in SGP8 treated mice (Fig. 4A). According to the results of the experiment, mice fed with the MCD diet showed the magnified contents of hepatic TG and TC in the NAFLD model group compared with the control diet-fed mice.The results of co-administration of SGP8 and MCD diets showed that SGP8 significantly reduced TG/TC content in NAFLD mice liver (Figs. 4B and C). The serum biochemical parameters of mice fed with MCD diet were assessed and found an increase in the serum LDL levels.However, when C57BL-6 mice fed with MCD diet were treated with SGP8, a reduction in serum LDL level was observed (Fig. 5A).Furthermore, SGP8 treatment obviously decreased ALT levels in MCD diet-fed mice (Fig. 5B). At the same time, liver SOD and MDA levels were also measured to assess antioxidant levels. The result indicated that SGP8 could significantly increase liver SOD activity (Fig. 5C) and effectively reduce the production of the peroxide marker MDA (Fig. 5D). Fig. 4 SGP8 reduced liver lipid accumulation in vivo. (A) Representative images of liver appearance, H&E and oil red O staining in liver sections under a microscope at 400× magnification. The arrow indicates vacuoles macro-vesicular steatosis of liver. (B) TC content in livers. (C) TG content in livers. Mice were fed with MCD diet or control diet for 3 weeks. Mice fed with MCD diet were intravenous injected with 1 and 5 mg/kg SGP8 daily in the period of experiment.Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). **P < 0.01 versus normal diet group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus MCD group. Fig. 5 SGP8 improves serum biochemical parameters and increases liver antioxidant levels. (A) LDL content in mice serum. (B) ALT content in mice serum.(C) SOD levels in mice liver. (D) MDA levels in mice liver. Mice were fed with MCD diet or control diet for 3 weeks. Mice fed with MCD diet were intravenous injected with 1 and 5 mg/kg SGP8 daily in the period of experiment. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus normal diet group; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus MCD group. Fig. 6 (Continued) Fig. 6 SGP8 promotes SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway activation in vivo. (A) Representative Western blot image of pACC, ACC, CPT1, FAS, and β-actin.(B) Western blot analysis showing effect of SGP8 on protein expression levels of CPT1 and FAS, and phosphorylation level of ACC. (C) Representative Western blot image of SIRT1, pAMPK, AMPK, PPARα, SREBP-1c, and β-actin. (D) Western blot analysis showing effect of SGP8 on protein expression levels of SIRT1,PPARα, and SREBP-1c, and total and phosphorylated levels of AMPK. Mice were fed with MCD diet or control diet for 3 weeks. Mice fed with MCD diet were intravenous injected with 1 and 5 mg/kg SGP8 daily in the period of experiment. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus normal diet group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus MCD group. Fig. 7 (Continued) Fig. 7 SGP8 reduces the expression of key in flammatory proteins in vivo. (A) Representative Western blot image of PPARγ, IL-6, TNF-α, and β-actin.(B) Western blot analysis showing effects of SGP8 on protein expression levels for PPARγ, IL-6, and TNF-α. Mice were fed with MCD diet or control diet for 3 weeks. Mice fed with MCD diet were intravenous injected with 1 and 5 mg/kg SGP8 daily in the period of experiment. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 versus normal diet group; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus MCD group. To determine the effects of MCD diet and SGP8 on adipogenesis and oxidation in the liver of mice, the protein expression of FAS,ACC, pACC and CPT1 was examined using Western blot. As shown in Figs. 6A and B, MCD diet attenuated pACC and CPT1 expression levels in the liver, which were enhanced by SGP8 treatment,particularly by high concentrations of SGP8. Compared to the control group, MCD diet enhanced the protein expression of FAS (Figs. 6A and B). After co-treatment with SGP8, the protein expression of FAS was significantly reduced compared to the model. The protein expressions of PPARα, SREBP-1c, AMPK, pAMPK,and SIRT1 were also assessed using Western blot. The expression of pAMPK and PPARα decreased significantly in the model group compared with the control group, and this effect was blocked in the presence of SGP8. On the other hand, the expression of SREBP-1c increased significantly in the model group compared with the control group, and the expression of SREBP-1c was reduced after SGP8 treatment (Figs. 6C and D). These results indicated that SGP8 may improve liver lipid metabolism by activating SIRT1/AMPK pathway. An important pathological feature of NAFLD is liver inflammation, and MCD diet has previously been shown to cause significant liver inflammation [40,41]. Key inflammatory proteins,including IL-6 and TNF-α, are particularly associated with liver inflammation and NAFLD progression [42,43]. To examine the anti-inflammatory effect of SGP8 in mice fed with MCD diet, the protein expression levels of these in flammatory markers and PPARγ in the liver were determined. As shown in Figs. 7A and B, PPARγ was significantly upregulated when co-administration of SGP8 and MCD diets compared with only MCD diets. In addition, the downregulation of IL-6 and TNF-α occurred after SGP8 treatment.These results revealed that treatment with SGP8 attenuated the in flammatory response induced by MCD diet. It is reported that SIRT1 and AMPK have a co-mediating effect on liver lipid metabolism [44]. On the one hand, SIRT1 promotes the phosphorylation of AMPK by affecting the deacetylation of LKB1. On the other hand, the phosphorylation of AMPK will promote NAD+level in the liver, so that SIRT1 exerts deacetylation activity. Previously, it has been reported that the downregulation of SIRT1 protein level in hepatocytes is the characteristic of NAFLD [45,46]. Consistent with the previous studies, this study observed that SIRT1 protein level decreased significantly in FFA induced steatosis model and MCD diet induced NAFLD model.However, a significant increase was observed in the expression of SIRT1 by SGP8 treatment. According to these experiments, it is clear that SGP8 can promote the expression of SIRT protein level. AMPK is a key molecule of energy balance in cells and the whole body, which is involved in the regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis [47].Site-directed mutagenesis experiments of AMPK indicate that Thr-172 phosphorylation in the catalytic domain of the subunit is necessary for AMPK activation [48]. The phosphorylation of AMPK can effectively improve the phosphorylation level of ACC and promote the inactivation of ACC in cells [49]. The activation of AMPK/ACC signaling pathway can inhibit TG production because ACC is the rate limiting enzyme for the synthesis of malonyl-CoA, which is the key substrate for fatty acid biosynthesis and an effective inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation [13]. Our results demonstrated that SGP8 may inhibit ACC activity by activating AMPK phosphorylation. PPARα is mainly expressed in liver, kidney and heart [50]. At present, there is credible evidence to support that PPARα plays an important role in liver lipid metabolism [51]. PPARα activation occurs after dimerization of retinoic X receptor (RXR), forming a multi-protein complex. In its active form, PPARα combines with typical receptor specific PPAR response elements (PPRE) to enhance the transcription levels of various fatty acid oxidation proteins [52].In the context of hepatic lipid overload, downregulated expression of CPT1 results in an overwhelming of fatty acid β-oxidation, leading to hepatic steatosis and lipid peroxidation [53]. In our study, the western blot results showed that SGP8 could effectively increase the level of PPARα and CPT1 in hepatocytes. Before the activation of SREBP-1c, SREBP-1c combined with SCAP and INSIG to form a large precursor on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane [37]. There is evidence that upstream transcription factor 1 (USF1) recruits SREBP-1c to combine with serum response element (SRE) for transcriptional activation in the SREBP-1c promoter region through direct interaction with SREBP-1c [54].The expression levels of fatty acid synthesis genes such as FAS and ACC were enhanced by recruitment of SREBP-1c [55]. Our experimental results showed that SGP8 could downregulate the level of SREBP-1c and decrease the expression levels of FAS and ACC.Previous studies have shown that the phosphorylation of AMPK can downregulate the expression of SREBP-1c and upregulate the expression of PPARα to improve the lipid metabolism of liver [55,56].Consistent with thisfinding, our results also showed that SGP8 could upregulate the expression of PPARα and downregulate the level of SREBP-1c by phosphorylating AMPK. In the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) performs the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, which eventually leads to the accumulation of intracellular peroxides [57]. Our results showed that SGP8 could effectively improve SOD activity and antioxidant capacity of liver. In flammation plays a central role in the development of liver damage during development of NAFLD [58]. There is evidence that PPARγ can attenuate the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α and IL-6 [14]. In order to determine the effect of SGP8 on liver in flammation, PPARγ and the key in flammatory proteins such as IL-6 and TNF-α were detected by Western blot. The results indicated that SGP8 might effectively improve in flammatory infiltration and avoid oxidative damage by upregulating PPARγ. Taken together, the results of the present study demonstrated the anti-NAFLD effects of SGP8 both in vitro and in vivo, and SGP8 might improve NAFLD by activating SIRT1/AMPK pathway to mediate lipid metabolism and upregulating PPARγ expression to attenuate in flammatory response in the liver (Fig. 8). Thesefindings can provide essential help for the research of SGP8 in the therapeutics of NAFLD. Fig. 8 Summary of the effect of SGP8 on MCD diet induced NAFLD. SGP8 activates the SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway to mediate lipid metabolism and inhibits PPARγ expression to attenuate in flammatory response in the liver. Con flict of interest The authors declare that there are no con flicts of interest. Acknowledgements This work was funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). The authors also thank Dr. Zhu Zhou (City University of New York) for her assistance in reviewing this manuscript and valuable discussion. Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2022.06.012.3. Results

3.1 FFA-induced steatosis in HepG2 cells

3.2 SGP8 improved steatosis of HepG2 cells

3.3 SGP8 promoted SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway activation in vitro

3.4 SGP8 reduced liver lipid accumulation in vivo

3.5 SGP8 improved serum biochemical parameters and increases liver antioxidant levels

3.6 SGP8 promoted SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway activation in vivo

3.7 SGP8 reduced the expression of key inflammatory proteins in vivo

4. Discussion

杂志排行

食品科学与人类健康(英文)的其它文章

- Production of antihypertensive and antidiabetic peptide fractions from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) by electrodialysis with ultrafiltration membranes

- Identification and characterization of a novel tetrapeptide from enzymatic hydrolysates of Baijiu byproduct

- Effects of phosvitin phosphopeptide-Ca complex prepared by efficient enzymatic hydrolysis on calcium absorption and bone deposition of mice

- Structural requirements and interaction mechanisms of ACE inhibitory peptides: molecular simulation and thermodynamics studies on LAPYK and its modified peptides

- Anti-diabetic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects of sea cucumber(Cucumaria frondosa) gonad hydrolysates in type II diabetic rats

- Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of peptide PvGBP2 against pathogenic bacteria that contaminate Auricularia auricular culture bags