Production of antihypertensive and antidiabetic peptide fractions from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) by electrodialysis with ultrafiltration membranes

2022-07-11AdriGonzlzMuozMarionVallRotimiAlukoLaurntBazintJavirEnrion

Adrián Gonzálz-Muñoz, Marion Vall, Rotimi E. Aluko, Laurnt Bazint*, Javir Enrion,*

a Biopolymer Research and Engineering Lab (BiopREL), School of Nutrition and Dietetics, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de los Andes,Monseñor Álvaro del Portillo 12455, Chile

b Centre for Biomedical Research and Innovation (CIIB), Universidad de los Andes, Chile, Monseñor Álvaro del Portillo 12455, Chile

c Institute of Nutrition and Functional Foods (INAF), Université Laval, Québec QC G1V 0A6, Canada

d Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Laval Hospital Research Center, Université Laval, Québec QC G1V 4G5, Canada

e Department of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg MB R3T 2N2, Canada

f Department of Food Sciences, Laboratoire de Transformation Alimentaire et Procédés ÉlectroMembranaire (LTAPEM, Laboratory of Food Processing and Electro-Membrane Processes), Université Laval, Québec QC G1V 0A6, Canada

ABSTRACT

Processing bioactive peptides from natural sources using electrodialysis with ultrafiltration membranes (EDUF)have gained attention since it can fractionate in terms of their charge and molecular weight. Quinoa is a pseudo-cereal highlighted by its high protein content, amino acid profile and adapting growing conditions.The present work aimed at the production of quinoa peptides through fractionation using EDUF and to test the fractions according to antihypertensive and antidiabetic activity. Experimental data showed the production of peptides ranging between 0.4 and 1.5 kDa. Cationic (CQPF) (3.01%), anionic (AQPF) (1.18%) and the electrically neutral fraction quinoa protein hydrolysate (QPH)-EDUF (~95%) were obtained. In-vitro studies showed the highest glucose uptake modulation in L6 cell skeletal myoblasts in presence of QPH-EDUF and AQPF (17% and 11%) indicating potential antidiabetic activity. The antihypertensive effect studied in-vivo in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR), showed a decrease in systolic blood pressure in presence of the fractionated peptides, being 100 mg/kg a dose comparable to Captopril (positive control).These results contribute to the current knowledge of bioactive peptides from quinoa by reporting the relevance of EDUF as tool to produce selected peptide fractions. Nevertheless, further characterization is needed towards peptide sequencing, their respective role in the metabolism and scaling-up production using EDUF.

Keywords:

Quinoa

Electrodialysis with ultrafiltration membranes

Bioactive peptides

Antihypertensive

Antidiabetic

1. Introduction

The demand for non-animal protein has been driven from the continue increase in global population and from environmental concerns associated to climate change and diseases related to animal sources [1]. These factors have encouraged research in non-traditional protein and the development of new products [2]. In fact, the demand of plant proteins is increasing projecting a market growth around compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.7% during the forecast period 2021–2026 (www.mordorintelligence.com).

One strategy to add value to protein-based food formulation is by the modification of protein structure, reducing the molecular size and producing peptides with biological activity or bioactive peptides (less than 15 amino acids residues) [3], which can interact at physiological level [3]. Research on bioactive peptides as potential therapeutic compounds for human diseases and aging [4] goes hand in hand with the improved consumer interest/awareness in health and wellness-promoting products [5]. The latter in response to global recommendations by WHO regarding the serious economic fallout in obesity and related health complications such as metabolic syndrome among the population in developing and developed countries [6].According to WHO, metabolic syndrome with its pathologic elements such as obesity, insulin resistance and hypertension, is the major health hazard of modern world [7]. Among these factors, type 2 diabetes and hypertension (cardiovascular disease), are considered as leading risk factors [8]. Diabetes has been associated with macrovascular diseases such as heart attacks, coronary artery disease,strokes, cerebral vascular disease and peripheral vascular disease,microvascular diseases and various type of cancers [9].

Considering the increase in demand for non-animal proteins,literature has reported several plants as a potential source of antidiabetic and antihypertensive bioactive peptides. For instance,peptides from beans with in-vitro ACE inhibition activity [10]and peptides from flaxseed, tested in-vivo using spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR), with antihypertensive properties [11]have also been produced. In terms of diabetes, peptides from rice fractionated by gel filtration have been shown to in-vitro inhibit the dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) enzyme [12], peptides from brewers’ spent grain fractionated by ultrafiltration and HPLC have also shown to in-vitro inhibit DPP-IV [13] and more recently, soybean peptides fractionated by ultrafiltration and solid phase extraction (SPE)showed inhibiting activity of DPP-IV, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase enzymes [14].

Quinoa seeds (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) are regarded as a good food source by both, the industry and consumers, due to their high protein content, balanced nutritional amino acids profile, and complete nutritional qualities [15] that are higher than other dietary grains such as wheat, rice, maize, oat, and barley [16]. This has been reflected in a rapid growing market [17]. In addition, quinoa also standouts from its stress-tolerant physiology, withstanding water shortage and different conditions in soil and salinity in isolated and extreme geographical conditions in a vast territory (e.g., Bolivia’s Altiplano and coastal zones) [17].

Therefore, over the years these features have generated a special interest processing quinoa seed for several applications, including the production of bioactive peptides, evaluated either in-vitro,in-silico, or in-vivo. In 2018, Orona-Tamayo et al. [18], indicated that limited information was available related to quinoa bioactive peptides, being necessary to carry out more studies to demonstrate the potential therapeutic properties of this pseudocereal. In this regard,in-vitro anticancer properties of quinoa peptides were observed after gastrointestinal simulation [19]. In-vitro anti-inflammatory activity of quinoa peptides produced after the digestion with papain, pepsin,and pancreatin [20], immune and anti-in flammatory effect by quinoa proteins following the Osborne classification (chenopodin) [21] and chronic in flammation and oxidative activity by quinoa albumins and globulins following simulated gastrointestinal digestion [22] have been obtained. Regarding the effect of peptides produced from quinoa on hypertension, Aluko and Monu [23] in pioneering work showed inhibitory activity of ACE using quinoa protein hydrolysate (QPH)obtained by using the enzyme alcalase and fractionated by ultrafiltration membrane (UFM). Zheng et al. [24] performed studies in-silico, in-vitro, and in-vivo, and highlighted a specific peptide sequence chemically synthesized (seven residues) as an antihypertensive peptide in SHRs. More recently, Guo et al. [25]reported in-silico and in-vitro inhibition of ACE, and in-vivo activity in SHRs of quinoa peptides after simulated gastrointestinal digestion.In their study, the higher systolic blood pressure (SBP) reduction was observed at the dose of 400 mg/kg of body weight (BW). They also identified 3 peptides (6 and 7 amino acidic residues) with ACE inhibition activity which potentially could have an antihypertensive activity. In the case of diabetes, Nongonierma et al. [26] produced quinoa peptides fractionated by gel permeation and HPLC-RP that inhibited DPP-IV. Vilcacundo et al. [27] studied inhibiting DPP-IV,α-amylase and α-glucosidase peptides after gastrointestinal simulation, and more recently, Guo et al. [25] studied through in-silico analysis using BIOPEP database and in-vitro experiments DPP-IV inhibiting peptides from quinoa stored protein.

It is well known that for the production of bioactive antihypertensive and antidiabetic peptides, physicochemical characteristics are needed to be preserved to promote the interaction with the above-mentioned enzymes or participate in other physiological processes. Among these factors, molecular weight and electrical charge have been highlighted. The former can be controlled through fractionation according to an UFM [28] and the latter by the use of changes in electrical potential [29]. In general,both processing approaches are generally performed separately or by one dimensional fractionation (it means one type of fractionation at the time). Nevertheless, combining both fractionation techniques is possible to enhance the bioactive activity of the produced peptide fractions [30]. UFM for fractionation according to molecular weight is considered to be cheap and easy to use [30]. However, some limitations are related to poor selectivity in the case of mixtures of peptides with similar molecular weight and by the presence of fouling on the membranes throughout the fractionation process [28,31].Therefore, the combination of UFM in an electrodialysis cell was developed [28], featuring a two-dimensional fractionation system [30].Electrodialysis with ultrafiltration membrane (EDUF) is a system that allows the fractionation of peptides from an hydrolysate according to electrical charge (positive/acid, neutral and negative/basic under the effect of the electricfield) and molecular weight (sieving effect of the UFM) [28]. EDUF can be regarded as a green processing technique since it does not require the use of chemical solvents [31]. This fractionation system has been successfully used for the production of antihypertensive cationic fractions from flaxseed rich in arginine peptides with molecular weight lower than 1.3 kDa [11] and between 0.3 and 0.5 kDa [32]. Also, it has been used to produce an antidiabetic anionic peptide fraction from soybean with molecular weight close to 0.3–0.5 kDa [33].

Considering the feasibility of peptide fractionation by EDUF, and the bioactivities reported by quinoa peptides, we report the assessment of combined EDUF processing technique for the production of peptides fractions from quinoa with well-defined molecular weight and electrical charge and to determine their bioactivity in terms of their potential in-vitro antidiabetic activity by glucose uptake and in-vivo antihypertensive activity by SHR animal model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation and characterization quinoa protein concentrate (QPC)

The protein extraction protocol from quinoa procedure was based on the work by Aluko and Monu [23]. Quinoa flour was dispersed in alkaline water (NaOH 40 mmol/L, pH ∼12) in a proportion of 1:30 (m/V) for 4 h. Then, the dispersion was centrifuged (Hettich Universal, 320R, UK) at 4 200 × g for 12 min at 8 °C, after which the soluble proteins were precipitated at pH 3.5 (isoelectric point) using HCl (2 mol/L), and centrifuged at 4 500 × g for 7 min at 8 °C. Finally,the pH of the protein concentrate was adjusted to pH 7.0 with NaOH,freeze-dried (Labconco Freezone plus, Kansas, MO, USA) and stored at -20 ºC until further use.

The amino acid composition of the quinoa protein concentrate was determined according to White et al. [34] by the use of reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Brie fly,10 mg of samples were hydrolyzed with 6 mol/L HCl at 150 °C for 1 h.Hydrolysates were derivatized with 20 μL of phenylisothiocianate(10%) to generate phenylthiocarbamyl amino acids plus the addition of phenol 1% (V/V). The analytical column used was an Inertsil ODS-3, C18(250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm). The HPLC system was equipped with a dual reciprocating plunger pump (Shimadzu LC 20AT, Japan), a column oven working at 40 ºC (Shimadzu CTO-20AC, Japan), and a UV/Vis lamp (Shimadzu SPD-M20A,Japan). The injection volume was 20 μL, the flow rate was 1 mL/min,and the eluates were monitored at 254 nm. The mobile phase was composed of solvent A (940 mL of 0.14 mol/L acetate buffer,containing 0.05% (V/V) of trietilamine, pH 5.85 and 60 mL of acetonitrile) and solvent B (60% (V/V) of acetonitrile). Initial conditions were: 100% A and 0% B, and a lineal gradient of solvent B was used: from 0% to 44% for 13 min, then from 44% to 94% for 9 min, then from 94% to 100% for 1.2 min, and then returned to the initial conditions for 5 min (total run time 30 min). Amino acids were identified by comparison of their retention times with those of pure standards (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany).

2.2 Preparation of QPH

QPH was obtained from the QPC described in section 2.1 according to Aluko and Monu [23] and del Mar Yust et al. [35]in a reactor with stirring and controlled temperature. QPC was suspended in distilled water at 5% in terms of protein concentration present in the concentrate. The hydrolysis parameters used were as follows: substrate concentration: 5%; enzyme concentration (by using Alcalase 2.4 U/g): 0.46 (V/V); temperature: 50 °C; pH 8. During the course of the reaction, the pH was kept constant at pH 8 by NaOH (2 mol/L). The enzymatic reaction was inactivated by heating the suspension to 85 °C for 10 min. The resulting suspension was cooled to room temperature and then centrifuged at 4 200 × g for 15 min at 8 °C. The supernatant was collected as QPH, freeze dried and stored at 20 °C until further use.

The degree of hydrolysis (%), defined as the percentage of peptide bonds cleaved, was measured by the pH-stat method quantifying the NaOH (2 mol/L) consumed to maintain pH 8 [36].

2.3 Fractionation by EDUF system

2.3.1 Electrodialysis cells and configuration

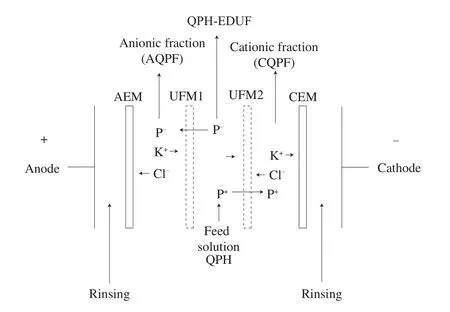

A MP electrodialysis type cell (ElectroCell Systems AB Company,Täby, Sweden) of 100 cm2of effective surface area, was used. A dimensionally stable anode (DSA), and a 316 stainless steel electrode cathode, were supplied with the MP cell. The difference of voltage between the anode and cathode was given by a power source of 0–100 V. The electrodialysis cell was composed of 4 membranes: one cationic exchange membrane (CEM) Neosepta CMX-SB, one anionic exchange membrane (AEM) Neosepta AMX-SB (both from Astom,Tokyo, Japan) and two polyether sulfone (PES) UFM with molecular weight cut off (MWCO) of 20 kDa (GE Infrastructure Water &Process Technologies). The electrodialysis arrangement (Fig. 1)was composed of 4 divisions, two for the recuperation and concentration of peptides, consisted of 2 L of KCl solution (0.2%):one of them was ubicated between the UFM1 and AEM (KCl-F1) and the other one ubicated between the UFM2 and the CEM (KCl-F2).Other compartment was for the electrode rinsing solution, contained 2% of Na2SO4(2 L) and the last one corresponded to the feed solution(2% of QPH in 2 L). The flow rate (by using flowmeters) for the feed solution, cationic and anionic fractions (permeate) were 2 L/min and for the electrode solution was 4 L/min. Four centrifugal pumps were used to circulate solutions.

Fig. 1 Configuration of the electrodialysis with UFM cell for quinoa peptide separation used in this study based on Udenigwe et al. [43].

2.3.2 EDUF separation procedure

Each electro-separation (batch system) was carried out during 6 hours, at ambient temperature (25–30 ºC), constant electric field of 20 V/cm and at QPH concentration of 2% (protein base). To promote the migration of electrically charged peptides, the pH of QPH, AQPH or CQPH compartments was maintained at pH 7.0 using 1.0 mol/L NaOH or HCl (monitored by a pH meter VWR Symphony SP20 equipped with a Thermo Scientific Orion 9206BN probe (VWR International Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada)).To maintain constant the peptide migration, conductivity of QPH,AQPH or CQPH were maintained constant (5.0–5.5 mS/cm) by the incorporation of KCl (YSI conductivity meter, model 3 100 equipped with a YSI immersion probe model 3252, cell constant K = 1 cm-1(Yellow Springs Instrument Co., Yellowsprings, OH, USA)). The product of EDUF fractionation by the indicated configuration, were three different quinoa peptide fractions: an anionic quinoa protein fraction (AQPF), cationic quinoa protein fraction (CQPF) (both fractions composed by peptides lower than 20 kDa), and a fraction that did not migrate, which will be named the hydrolysate post EDUF (QPH-EDUF), which was composed by peptides with neutral charge, or charged peptides with a molecular weight higher than the UF membrane (20 kDa) or with not time to migrate. Fouling formation was evaluated before and at the end of EDUF processing (4 runs of 6 h) by electrical conductivity and thickness determination of UFM1,UFM2, AEM and CEM. At the end of processing, the electrodialysis cell was dismantled and UFM1, UFM2, AEM and CEM were soaked into a 0.5 mol/L NaCl solution for 1 h to decrease electrostatic attractions and then to allow the recovering of electrostatically adsorbed quinoa peptides at the membrane surfaces [37].

2.3.3 Demineralization

At the end of complete EDUF performance (4 runs), each AQPF and CQPF were combined and demineralized by electrodialysis to discard salts (mainly KCl) for later bioactivity tests [11]. Initial unprocessed QPH was not further demineralized since its conductivity was low (lower than 33 μS/cm). The demineralization was performed under an electricfield of 10 V during thefirst 1 h and then 20 V until constant conductivity, and the required time to achieve it will be reported.

2.4 Characterization of the EDUF peptide fractions

2.4.1 Total protein content

The protein content in the final QPH-EDUF, AQPF and CQPF was determined according to the Dumas method for total nitrogen by combusting a sample of known mass with oxygen at a temperature~900 °C using FP-428 LECO (LECO, St. Joseph, MI, USA) [29].

2.4.2 Total peptide concentration

The peptide concentration in the AQPF, CQPF and QPH-EDUF solutions taken before to administrate voltage (electro-separation) and every hour during the 6 h of EDUF processing were obtained using microBCA™ protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford,IL, USA). Sample aliquots (1.5 mL) were taken, and the assays were conducted using microplates by mixing 100 μL of the peptide sample with 100 μL of the working reagent (37 °C for 0.5 h). The microplates were then cooled down to room temperature and an absorbance of 562 nm was used (THERMOmax, Molecular devices, Sunnyvale,CA, USA). A calibration curve was obtained to determine peptide concentration by using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard(25–2 000 μg/mL) [38].

2.4.3 Molecular weight of peptides

To determine the molecular weight of peptides, present in the QPH and in the AQPF, CQPF and QPH-EDUF fractions, mass spectrometry analyses were carried out. To obtain the spectra, 1 μL of each sample was mixed with 1 μL of the α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/mL in acetonitrile 50% (V/V) and formic acid 0.1% (V/V) (this matrix is preferably used for peptides of molecular weight less than 10 000 Da) on a micro scout sample plate (Bruker Daltonics Inc., MA-USA). Additionally, 1:10 dilutions in nano pure water of each sample were prepared for which the spectra were acquired by mixing 1 μL of each dilution with 1 μL of the matrix in a sample holder plate. The acquisition of mass spectra was carried out in a MALDI-TOF Microflex equipment (Bruker Daltonics Inc.,MA-USA) in positive ion mode by detection by reflection. Prior to obtaining the spectra, the equipment was calibrated with an external standard corresponding to a mixture of peptides with masses 650–2 000 Da. The FlexControl 3.0 program (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany) was used to control the spectrometer. The final spectra correspond to the sum of 10 scans of 30 laser hits (300 laser hits in total) applied at different points taken at random from each mixture deposited on the sample plate.

2.5 Bioactivity of the EDUF peptide fractions

2.5.1 Glucose uptake on the cell model

Based on Tremblay and Marette [39], neonatal rat thigh L6 cell skeletal myoblasts muscle, were kindly provided by Dr. A. Klip from Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, ON, Canada). Cells were grown and kept in monolayer culture using 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)–α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM) (incubated at 5% CO2and 37 °C). After that (48 h), L6 myoblasts were plated into 24-well plates (5 × 105cells/plate) in 2% FBS–α-MEM. Myoblasts were used after complete differentiation to myotubes (corresponding to 7 days post-plating).

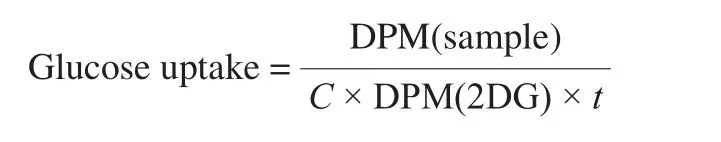

During 4 h, L6 Myotubes had no contact with FBS and were treated or not with the quinoa peptides fractions obtained by EDUF treatment at two concentrations (1 ng/mL and 1 μg/mL)for 1 h without insulin (basal) or with 100 nmol/L insulin for the final 45 min. Comparisons of glucose uptake were indicated between L6 cells treated or not with insulin (stimulated), using 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) [39]. Briefly, L6 cells were washed once with 37 °C HEPES-buffered solution (20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4,140 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 2.5 mmol/L MgSO4, and 1 mmol/L CaCl2) and then incubated during 8 min in transport medium (HEPES-buffered solution containing 10 µmol/L unlabeled 2-DG and 0.3 µCi/mL D-2-deoxy-[3H] glucose). After that, cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold 0.9% NaCl solution (4 ºC) and lysed (disrupted) by adding 50 mmol/L NaOH. Cell-incorporated radioactivity was obtained by scintillation counting. After cells were treated with quinoa peptide fractions, wells were washed with glucose-free HEPES buffered solution (20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4,140 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 2.5 mmol/L MgSO4and 1 mmol/L CaCl2), and incubated for 8 min in transport medium (HEPES-buffered solution containing 10 µmol/L unlabeled 2-deoxy-D-glucose solution and 0.3 µCi/mL of 2-deoxy-D-[3H] glucose). After that, cells were washed 3 times as previously described. Cell-incorporated/associated radioactivity was obtained by scintillation counting and protein concentrations were determined according to the procedure indicated in section 2.4.2. Glucose uptake expressed in pmol of glucose/min per mg of protein was calculated using the following equation:

where, DPM(sample) corresponds to the number of disintegrations per minute (DPM) measured for the sample,Cthe concentration of protein (in mg), DPM(2DG) the number of DPM measured for the solution of radioactive 2-deoxy-D-[3H] glucose for 1 pmol, andtthe total incubation with 2-deoxy-D-[3H] glucose in 1 min.

2.5.2 SBP by animal model

Animal experiments were carried out following the Canadian Council on Animal Care Ethics guidelines with a protocol approved by the University of Manitoba Animal Protocol and Management Review Committee. Male SHR (n= 12) of 6-week-old [11],weighting 250–300 g, were obtained from Charles River (Montreal,PQ, Canada), and were housed under a 12-h day and night cycle at 21 °C with regular chow feed (standard laboratory diet) and tap waterad libitum(free access). Each experimental group was composed of 4 animals: phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (negative control),Captopril (10 mg/kg BW dissolved in PBS) (positive control), and QPH (100 mg/kg BW dissolved in 1 mL PBS). Each animal was orally gavaged with a 1 mL solution using a disposable plastic syringe and blood pressure was then registered continuously in free-moving animals for 24 h by telemetry (the effects of samples on SBP were compared to that of captopril).

2.5.3 Surgical implantation of telemetry sensors

The surgical implantations of telemetry sensors with Data Sciences International (DSI) HD-S10 telemetry transmitters (DSI, St. Paul,MN, USA) were carried out after one-week acclimation under sterile conditions. Surgical implantation of sensors was performed according to previously described protocols [40]. SBP, diastolic blood pressure(DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate were determined.

2.5.4 Telemetry recording and signal processing

Blood pressure acquisition (systolic and diastolic) was carried out in a quiet room with each animal cage placed on top of one receiver (Model RPC-1, DSI instruments, MN, USA). Real-time experimental values (SBP, DBP, MAP, and heart rate) were registered continuously using the Ponemah 6.1 data acquisition software (DSI instruments, MN, USA). An APR-1 atmospheric-pressure monitor(DSI instruments, MN, USA) was connected to the system and used to normalize the transmitted pressure data. In this way, the registered blood pressure signals were independent of atmospheric pressure fluctuations. The results of SBP, DBP, MAP, and heart rate at 2, 4, 6,8, 12, and 24 h are given by subtracting values at time zero.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Evolution of hydrolysis degree and peptide migration were subjected to a measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) (P< 0.05 as probability level for acceptance) using Statgraphics software Centurion XV.I (Stat Point Inc., USA), and SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), respectively. A test of comparison of two means (t-test) (P< 0.05 as probability level for acceptance)was used to compare glucose-transport array value between different peptide fractions. Blood pressure lowering effect using SHRs were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (P< 0.05 as probability level for acceptance).

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of QPC

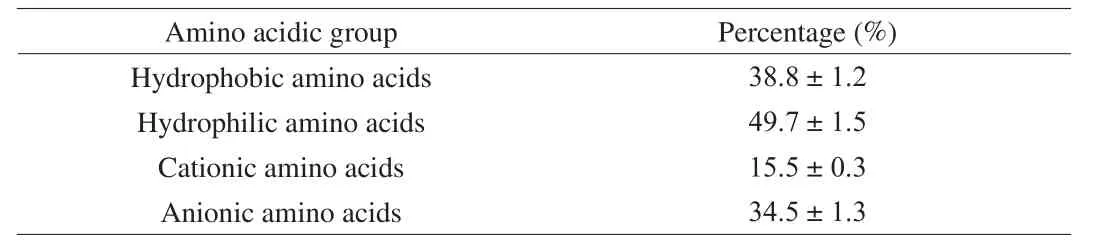

To produce sufficient material for furtherin-vitroandin-vivotests, a series of protein extractions were carried out to produce approximately 350 g of QPC. The proximate composition was,in dry base: 57.3% protein, 22.7% lipids, 5.5% ash, and 14.5% no nitrogen compounds. The QPC was composed of a high concentration of lipid because removal of lipid fraction was not considered and for the same reason, the protein content was lower than a protein isolate. Amino acids present in the protein concentrate were grouped according to hydrophobic, hydrophilic,anionic, and cationic amino acids (Table 1). Of relevance to this study according to separation by EDUF, the anionic amino acid group was present in 34.5% and was higher in concentration compared to the cationic amino acid group (15.5%).

Table 1Amino acidic composition of QPC according to hydrophobic, hydrophilic,cationic, and anionic amino acids.

3.2 Hydrolysis from QPC

The degree of hydrolysis of QPC after processing by the enzyme Alcalase 2.4 U/g is presented in Fig. 2. The hydrolysis rate was higher for the first 20 min, with a degree of hydrolysis value of(12.4 ± 0.6)%. After 1 h of hydrolysis, reached (18.3 ± 1.8)%, and after 6 h period, the reaction rate was lower but reach afinal degree of hydrolysis of (23.4 ± 1.7)%. These results are in accordance with the work of García-Mora et al. [41]. They used several enzymes (alcalase,savinase, protamex and coralase), to hydrolyze proteins from lentil obtaining the highest degree of hydrolysis value when alcalase was used (23%). In a similar work, Medina-Godoy et al. [42] studied the use of microbial enzymes, papain and pancreatin for the hydrolysis of chickpeas proteins, obtaining the highest degree of hydrolysis (~16%)by alcalase after 2 h of processing. This was explained by the higher efficiency of hydrolysis of alcalase, being more effective than other endopeptidases such as papain and pancreatin as it cleaves bonds of hydrophobic amino acid residues. Papain is known for cleaving sites preceded by Phe, Val and Leu, while pancreatin seems to have less specificity on the sites that it cleaves [42]. These results suggest the production of QPH with small molecular weights.

Fig. 2 Degree of hydrolysis of the quinoa protein concentrate as a function of hydrolysis time. Results are given as mean ± standard deviation (triplicate).Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.3 Fractionation of QPH by EDUF

3.3.1 Peptide migration

QPH suspensions were adjusted to pH 7 according to Udenigwe et al. [43] in order to separate cationic and anionic peptides during EDUF processing. A lower pH value than the isoelectric point (pI),peptides present a positive charge [33] and the lateral group of cationic amino acids such as Arg (pI = 10.76, pKaR= 12.48) and Lys (pI = 9.74, pKaR= 10.53) will be positively charged while the rest of amino acids will be negatively charged or remain neutral [43].As EDUF progressed (at pH 7), there was a significant migration of peptides (P < 0.05) from the hydrolysate to both compartments,anionic (AQPF) and cationic (CQPF) (Fig. 3), similarly to other reports using the same separation technique [32,33]. However, it is possible to observe at the end of the 6 h of EDUF, the migration of cationic peptide fraction was significantly higher than AQPF(P < 0.05). A mass balance showed (411.1 ± 45.0) mg of CQPF and(253.0 ± 33.8) mg of AQPF. This migration represented 3.01% and 1.18% of the total QPH processed by EDUF for CQPF and AQPF fractions respectively. A similar proportion of migrated cationic peptides from flaxseed hydrolysates fractionated by EDUF at the same pH has been previously reported by [43], and for herring milt [44]. According to Roblet et al. [45] and Durand et al. [44],this difference was explained by a higher concentration of cationic peptides in the QPH at pH 7 of electro-separation.

Fig. 3 Peptide migration at pH 7 of CQPF and AQPF after EDUF 6 h of treatment. Results are given as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4).

At the end of each EDUF run (total run were 4), the fouling of the membranes (UFM, AEM and CEM) were evaluated (data no shown).As no significant increment was observed, the same membranes were used for all the fractionation runs.

3.3.2 Demineralization

In order to favor peptide migration during EDUF, the conductivity of feed and recovery (permeate) solutions was maintained constant to 5.0–5.5 mS [29] by the use of KCl solutions. In order to be able to test the recovery fractions, mainly for the in-vivo bioactivity testing, the peptide fractions were demineralized. Demineralization was carried out by electrodialysis for 270 min, after which 95.5% of KCl was removed from AQPF. In the case of CQPF, 92.0% was removed after 330 min of processing.

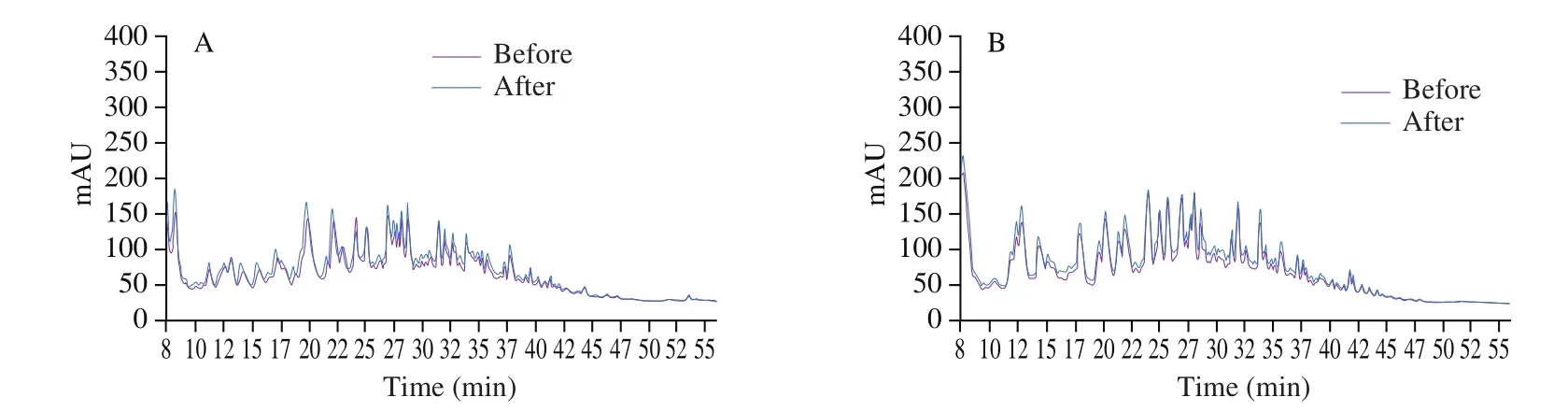

The chromatographic profile of both fractions obtained by HPLC-RP before and after the electrodialysis demonstrated that no peptides were apparently lost during the demineralization process (Fig. 4).

3.4 Characterization of QPH fractions (molecular weight)

MALDI-TOF analysis of QPH, AQPF and CQPF fractions showed peptides with molecular weight between 0.4 and 1.5 kDa(hydrolysate mass spectrum is given as an example (Supplementary information Fig. S1)). The reported average molecular weight of amino acids is about 0.11 kDa [46], which would correspond to 3 and 13 amino acids per unit. These results support the high values of the degree of hydrolysis reported in the previous section (23%).Low molecular weight peptides have been commonly related to bioactivity [3,47] as shown by peptides obtained by EDUF with antidiabetic activity [45].

Fig. 4 Chromatographic profiles before and after demineralization of (A) AQPF and (B) CQPF.

3.5 Bioactivity of QPH fractions

3.5.1 Antidiabetic effect

The effects of quinoa QPH fractions on glucose uptake test (Fig. 5)were carried out at concentrations of 1 ng/mL and 1 μg/mL of peptide, considering two different conditions: without (basal)or with the incorporation of insulin (INS). At both concentrations evaluated, the stimulation with insulin significantly improved the glucose uptake response (P < 0.05) in all the samples.

Fig. 5 Glucose-transport assay of QPF-EDUF, AQPF and CQPF fractions tested at (A) 1 ng/mL and (B) 1 μg/mL. INS: insulin. *Sample values are significantly different (P < 0.05) compared with basal condition. **Sample values are significantly different (P < 0.05) compared with insulin treatment.

Testing a concentration of 1 ng/mL at basal and INS conditions,QPH-EDUF and AQPF fraction showed an increase, although non-significant (P > 0.05), in glucose uptake compared with control,being higher for AQPF (increase of 5.3% for basal and 7.4% for INS)compared with QPH-EDUF (increase of 4.0% for basal and 3.1% for INS). In the case of CQPF, interestingly an increase in glucose uptake was not observed, moreover a significant reduction (P < 0.05)(6.7%) was detected for the samples at basal condition indicating a no antidiabetic effect, probably due to the presence of inhibitory peptides. A similarfinding was reported by Henaux et al. [48] after EDUF separation of salmon hydrolysates, in particular by the cationic fraction on L6 muscular cells. However, the decrease in glucose uptake with the cationic fraction from salmon was 15% higher than our findings. This difference was probably due to the source of peptides (salmon vs quinoa), protein concentration present and the molecular size of peptides (shorter peptides were obtained from salmon processing than the peptides from quinoa).

For 1 μg/mL, all the fractions showed a higher glucose uptake compared to control. We believe this is thefirst time the enhancement of the glucose uptake capacity by QPH after EDUF separation is reported. Comparing to the data reported for the 1 ng/mL, a dose-dependent activity was observed. In terms of the sample at basal condition, at 1 μg/mL, the increase was 17.1%, 11.1% and 3.1% for QPH-EDUF (P < 0.05), AQPF (P < 0.05) and CQPF (P > 0.05),respectively. A similar response at basal conditions was previously reported but with salmon protein hydrolysate [45,48].

In the case of the samples with INS, all fractions showed a higher glucose uptake response with an increase of 11.1% (P > 0.05),17.9% (P < 0.05), and 5.6% (P > 0.05) for QPH-EDUF, AQPF and CQPF, respectively compared to the control with INS. However,only the effect of INS on AQPF was significant (P < 0.05). At this concentration, no fraction showed a decrease of glucose uptake as it was observed for 1 ng/mL.

Therefore, an overall increase in glucose uptake observed in the cells model was higher for AQPF, followed by QPH-EDUF, but no improvement was observed by CQPF. These results are in agreement with the literature [33,45], in which the anionic fraction from salmon and soy composed by short peptides (< 1 kDa) showed a significant increase in glucose uptake by L6 muscle cells (cationic fraction did not show a significant increase) and the QPH-EDUF was not tested.Information related to physiological mechanisms that could explain the effect of peptides on glucose metabolism is limited. Most of the literature looking at bioactive food peptides explore the reduction in gastrointestinal enzymatic activity related to carbohydrates such as α-amylase and α-glucosidase [27], or the enzyme DPP-IV related to the production of insulin [25,26].

One possible therapeutic target by bioactive peptides could be the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)enzyme (phosphorylation) [49] which participate in enhancing the glucose uptake in muscle cells [33,50]. Charged peptides from soy protein hydrolysates fractionated by EDUF tested in L6 muscle cells lines have shown to be capable to activate AMPK [33]. An anionic peptide (11 amino acids residues) derived from casein showed to prevent high glucose levels in hepG2 cells by activating AMPK signaling pathways via phosphorylation of Akt (protein kinase B) and AMPK [51]. Also 3 anionic peptides derived from soy (composed of 4 and 8 amino acid residues), were identified to be responsible for the activation of AMPK through an increase of phosphorylation at Thr172, which activated other targets increasing the activation of glucose transporters and glucose uptake by HepG2 cell line [52].

3.5.2 Antihypertensive effect

The potential antihypertensive activity of QPH-EDUF, AQPF and CQPF were studied according to SBP, DBP (Fig. 6), mean arterial pressure and heart rate (Supplementary information Fig. S2) using SHR (SBP over 150 mmHg).

Following oral administration by gavage and using a dose of 100 mg/kg BW, the effect of all fractions was compared to Captopril(positive control) (10 mg/kg BW) at different times.

The generated data on SBP showed, as expected, significant differences (P < 0.05) between negative control (saline, PBS)and positive control (Captopril) (Fig. 6A). After a short time of administration, all the rats exposed to the EDUF fractionated samples showed a reducing effect in SPB for about 8 h, however, QPH-EDUF had the highest response after 2–6 h. This fraction showed a strong hypotensive effect, surpassing even the effect of Captopril, although the dose was different. Interestingly, this fraction also showed a dual activity over 12-h and 24-h periods. Indeed, two “subgroups” were observed in terms of SBP reduction; one between 2 and 6 h and a second between 8 and 24 h, indicating an immediate and delayed response. It could be hypothesized that the variety of peptide sizes and sequences within the fraction could affect their metabolization over time, short peptides (400–1 500 Da) acting first which can be quickly absorbed and then the second group with larger sequences being metabolized at a lower rate. AQPF and CQPF had a lowering effect up to 8 h, after which their effect was reduced.

Fig. 6 Changes in (A) SBP and (B) DBP of spontaneously hypertensive rats(SHRs) (n = 4) as a function of time after oral administration of 100 mg/kg BW of QPH-EDUF, AQPF and CQPF fraction in comparison to 10 mg/kg BW of captopril. * at the same level, indicate that values are significantly different (P < 0.05) than the values for saline (negative control)and ** at the same level, indicate significant differences between captopril(positive control) and tested samples (P < 0.05).

Overall, the highest reducing effect of SBP was achieved at 6 h by the QPH-EDUF fraction, reaching (-29.10 ± 4.41) mmHg. After the same time, Captopril (C+) had a reducing effect on SBP of(-17.49 ± 4.66) mmHg. The higher reducing effect (P < 0.05) at each monitoring time was as follows: QPH-EDUF at 4 h (> C+) and 6 h (> C+), CQPF at 8 h (> C+), QPH-EDUF at 12 h (> C+) and at 24 h (> C+). Guo et al. [53] also reported antihypertensive activity in SHRs after the administration of quinoa peptides produced by simulated gastrointestinal digestion. In their case, they reported a maximum decrease of SBP at 6 h after administration (-33.1 mmHg).Nevertheless, the decrease was observed when the higher tested dose was administered (400 mg/kg BW), which is 4 times higher dose compared with our results. They also used a dose of 100 mg/kg BW,and the decrease of SBP was close to -15 mmHg. This difference could also be explained by the protocol to obtain the peptides. Our process did not follow a simulating gastrointestinal digestion, in which the enzymes present are more site-specific resulting in a lower hydrolysis degree, which can explain the lower SBP decrease at the same dose (100 mg/kg BW). Another difference worth highlighting is that those authors evaluated SBP increase to until 10 h later, therefore it was not possible to observe a possible second subgroup of active peptides, as we did in our work, having SBP evaluated for 24 h.Zheng et al. [24] reported in-vivo antihypertensive activity from a quinoa peptide, but in this case they used a chemically synthesized octapeptide selected after an in-silico and in-vitro analysis. They reported the effect of various doses (50, 100, and 150 mg/kg BW),showing antihypertensive being less effective when compared with captopril (14 mg/kg BW), with no significant dose-dependent relationship between high- and medium-dose groups. This cannot be directly compared with our study since our focus was to evaluate EDUF as effective process to generated peptides fraction with varying bioactivity and not a synthetic peptide.

In the case of the effect of the QPH fractions on DBP (Fig. 6B),similar results to SBP were observed, although in this case the greater effect was obtained by QPH-EDUF fraction after 12 h,with a reduction in DBP of (-21.78 ± 1.25) mmHg. Apart from 2 h after ingestion, with the highest reduction effect obtained by AQPF (< C+), for all the rest of the monitored times the QPH-EDUF fraction showed the greater lowering effect on DBP. As mentioned in the previous section, QPH-EDUF fraction showed an interesting dual effect on SBP at short and long times after oral administration.

Mean arterial pressure measured during a single cardiac cycle,involving SBP and DBP (Supplementary information Fig. S2),showed that QPH-EDUF increased mean arterial pressure significantly (P < 0.05) compared to saline and Captopril treatment, at all monitoring times shorter than 12 h after oral administration. In the case of AQPF and CQPF, non-significant differences in mean arterial pressure values (P > 0.05) compared to saline or Captopril were observed. Regarding to heart rate, the values were similar between all the fractions, except at 8 h after administration, where the effect of QPH-EDUF was significantly higher than saline and Captopril treatment. No treatment showed significantly lower values than Captopril. A slightly different result was indicated by Marie et al. [11],in which saline treatment showed a higher mean arterial pressure than peptide fraction and Captopril. Also, heart rate was only significantly different after 2 h gavage, being peptide fractions lower than Captopril. This difference could be attributed to the different protein sources used (flaxseed) and/or to the differences in the electro-separation process such as pH (pH 3 versus our treatment at pH 7).

These results show the relevance of using a combined EDUF processing setting, such as EDUF to produce quinoa bioactive peptides. It showed that relatively low doses of 100 mg/kg BW show significant reductions in SBP compared to other protein sources processed by EDUF such as flaxseed [11,32], hemp seed protein hydrolysates [54] and rapeseed [17].

4. Conclusion

Quinoa protein concentrate was highly hydrolyzed by Alcalase producing short-chain peptides, which were successfully fractionated by EDUF, generating three fractions below 10 kDa in terms of their electrical affinity. QPH-EDUF and AQPF fractions were able to modulate L6 cell glucose, presumably by activation of key signaling targets in the cells, indicating a potential antidiabetic effect.QPH-EDUF and CQPF were effective in reducing SBP in SHR, with the former showing dual activity over 12 and 24 h period.

These results are promising and of interest since this work expands the use of combined EDUF on processed QPH, which were successfully tested as a potential antihypertensive and antidiabetic food. Although further characterization is needed to establish the peptide sequences which are specifically participating in the bioactive response in both metabolic conditions.

Con flict of interest

The authors declare there is no con flict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was financially supported by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Nº 3190683 of Dr. Adrián González-Muñoz from the Chilean Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada(NSERC) Discovery Grant Program (Grant SD RGPIN-2018-04128 of Prof. Laurent Bazinet). The authors would like to specially thank Jacinthe Thibodeau from the Department of Food Sciences, Université Laval for her technical support.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2022.06.024.

杂志排行

食品科学与人类健康(英文)的其它文章

- Identification and characterization of a novel tetrapeptide from enzymatic hydrolysates of Baijiu byproduct

- Effects of phosvitin phosphopeptide-Ca complex prepared by efficient enzymatic hydrolysis on calcium absorption and bone deposition of mice

- Structural requirements and interaction mechanisms of ACE inhibitory peptides: molecular simulation and thermodynamics studies on LAPYK and its modified peptides

- Anti-diabetic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects of sea cucumber(Cucumaria frondosa) gonad hydrolysates in type II diabetic rats

- Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of peptide PvGBP2 against pathogenic bacteria that contaminate Auricularia auricular culture bags

- Lunasin peptide promotes lysosome-mitochondrial mediated apoptosis and mitotic termination in MDA-MB-231 cells