Risk factors for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography(ERCP) abdominal pain in patients without post-ERCP pancreatitis

2022-06-02MengJieChenRuHuZhengJunCoYuLingYoLeiWngXioPingZou

Meng-Jie Chen , # , Ru-Hu Zheng , # , Jun Co , Yu-Ling Yo , Lei Wng , Xio-Ping Zou , b , *

a Department of Gastroenterology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital Clinical College of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

b Department of Gastroenterology, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, China

Keywords:Post-ERCP abdominal pain Cholangiopancreatography Endoscopic retrograde Pancreatitis Risk factor

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Abdominal pain is often observed in patients after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which sometimes indicates complications such as post-ERCP pancreatitis, perforation, or cholangitis. The most common complication with postprocedure abdominal pain is acute pancreatitis, which occurs in 3.0%-14.7% of the cases [1–3] and leads to death in 0.1%-1.1% of the patients [ 2 , 4 ]. For clinicians, fear of severe complication with abdominal pain may lead to anxiety and excessive treatment. Moreover, post-ERCP pain may influence the satisfaction and mental state of patients.

Most of the researches on the abdominal pain associated with ERCP aimed at solving the pain during the procedure [5] . Post-ERCP abdominal pain is one of the major symptoms of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP); however, abdominal pain after the procedure also indicates potential occurrence of post-ERCP cholangitis, perforation or nonspecific etiology (flatulence, gastric and intestinal spasm, etc). Few studies have focused on the characteristics and risk factors of post-ERCP abdominal pain without PEP.

Therefore, this study aimed to identify the characteristics and risk factors of post-ERCP abdominal pain without PEP. Differences between abdominal pain with or without PEP were compared so as to guide clinical diagnosis and decision-making.

Methods

Study design and patients

In this retrospective study, all patients who underwent ERCP from August 2019 to January 2020, at Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Drum Tower Clinical Medical College were included.Exclusion criteria included any of the following: 1) presence of any existing diseases that can cause acute or chronic abdominal pain (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, using antidepressant agents, persistent analgesia for cancerous abdominal pain); 2) cases that missing any of the indicators.

Data collection

The following data were extracted from the medical charts: 1)patient-related factors including sex, age, upper abdominal surgery history, lower abdominal surgery history, alcohol consumption,smoking, acute/chronic pancreatitis, coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, laboratory test results (routine blood test, liver function, tumor marker, coagulation function, etc), and underlying diseases; 2) procedure-related factors including precut sphincterotomy, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD), endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation(EPLBD), papilla opening (defined as joint name of EST, EPBD and EPLBD), difficult biliary cannulation (cannulation attempts of duration>10 min, and/or>5 attempts), operator experience (high grade:>200 ERCP procedures total and/or>50 procedures/year);3) postoperative outcomes including visual analogue scale (VAS)score of post-ERCP abdominal pain, pain onset, duration and frequency, use of analgesic medicine, use of protease inhibitors, total hospital stay, and hospital stay after ERCP. Intravenous anesthesia with propofol and remifentanil was induced in patients before and during ERCP. Indomethacin suppository was given routinely and prophylactic pancreatic stents were inserted in selected patients depending on the evaluation of the operator. ERCP with endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) would be conducted in patients with acute cholangitis requiring bile drainage or patients who need to relieve obstructive jaundice before surgery. A virgin papilla could be maintained in ERCP with ENBD only in such circumstances. Serum amylase was tested at 3 h, 12 h and 24 h after procedure. If the patient presented with new or aggravated epigastric pain within 24 h after procedure, abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and, if necessary, protease inhibitor or analgesic medicine was given.

Definitions

PEP is diagnosed with 2 out of 3 diagnostic criteria defined by the Revised Atlanta Classification (pancreatic abdominal pain,three folds upper normal limit of serum amylase, imaging suggestive of pancreatitis). Post-ERCP cholangitis is defined as new onset of fever (>38 °C, lasting over 24 h) and cholestasis. Post-ERCP perforation is defined with imaging evidence of gas or luminal contents outside of the gastrointestinal tract. Post-ERCP bleeding is diagnosed with hematemesis and/or melena or hemoglobin drop>2 g/dL or bloody fluid from nasobiliary drainage. Severity grading is conformed with European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy(ESGE) guideline 2019 [6] . Post-ERCP abdominal pain is diagnosed as a new or aggravated upper abdominal pain within 24 h after ERCP. Nonspecific pain after ERCP is defined as the pain resulting from non-organic disease after ERCP. Gastric and intestinal spasm is defined as colic after ERCP that can relieve spontaneously or by spasmolytic. Visceral traction pain is defined as instant onset of nonspecific abdominal pain after ERCP relieved by analgesic rather than spasmolytic.

Statistical analysis

The continuous data were dichotomized according to the cutoff value of each indicator based on clinical significance or normal range. Categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages and were compared with Chi-square test or Fisher’s test.The continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (range). The relevant factors found by univariate analyses (P<0.15) and variables which were found to be risk factors in previous studies were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis (forward stepwise regression selection).A receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was used to examine the sensitivity and specificity, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used for discrimination. Propensity score matching was performed to compare the realistic differences of post-ERCP abdominal pain between the PEP group and non-PEP pain group. Prior to propensity matching, Student’sttest or Chi-square test was used to compare indicators between groups. McNemar’s test was used for binary variables, and a paired Student’sttest or rank sum test was used for continuous variables. Statistical significance was defined as aPvalue<0.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS 25.

Results

Patients characteristics

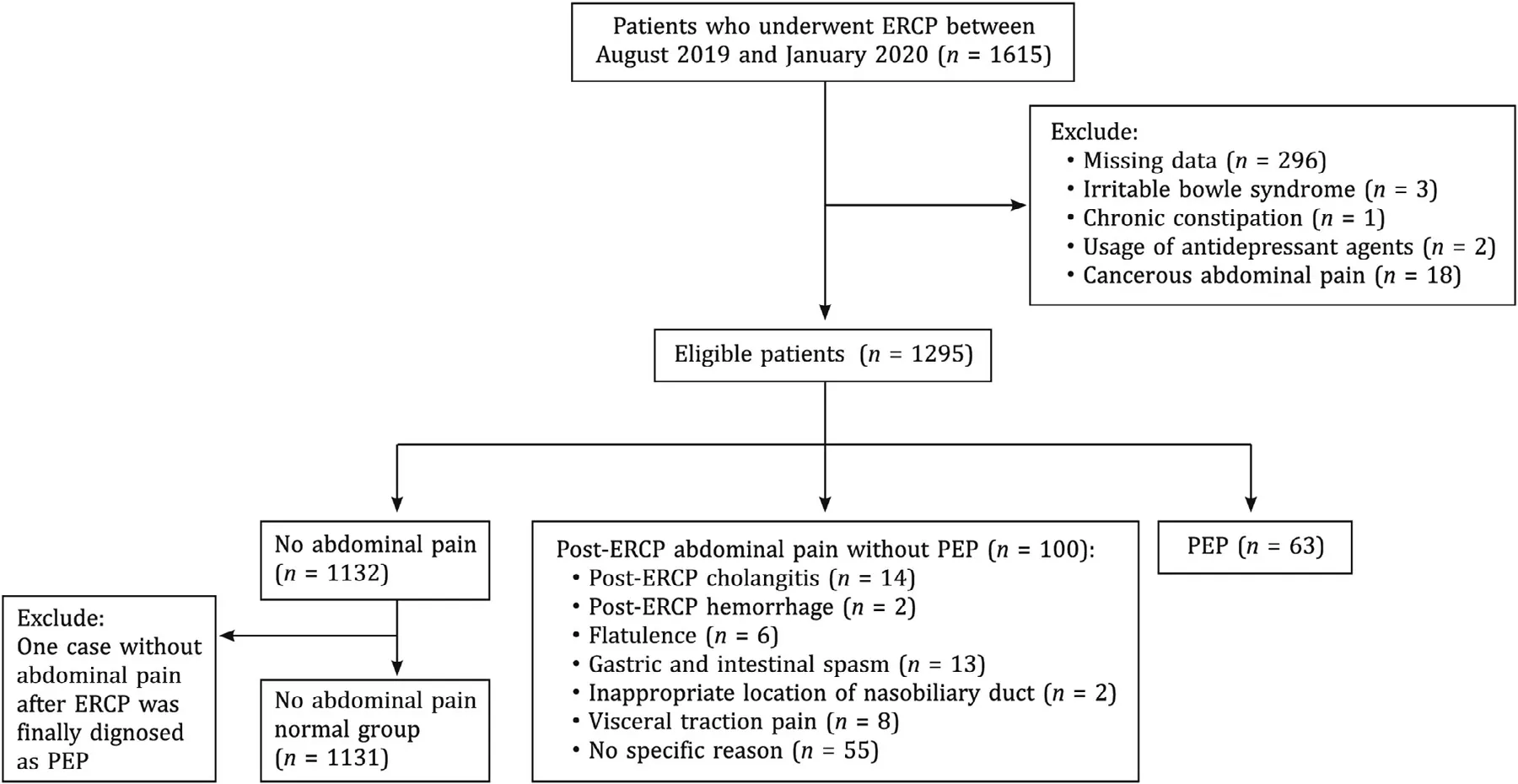

Data of 1615 patients who underwent ERCP were collected. After screening, 296 patients were excluded because of the missing data. One had chronic constipation, 3 had irritable bowel syndrome, 2 used antidepressant agents regularly and 18 used persistent analgesia for cancerous abdominal pain. The remaining 1295 patients were enrolled in the study ( Fig. 1 ). Among these patients,63 (4.86%) developed PEP with post-ERCP abdominal pain, and 100(7.72%) presented post-ERCP abdominal pain without PEP, including 14 post-ERCP cholangitis, 2 post-ERCP hemorrhage and 84 nonspecific abdominal pain (6 presented with flatulence, 13 presented with gastric and intestinal spasm, 2 resulted from inappropriate location of nasobiliary tube, 8 resulted from visceral traction pain and 55 had no specific reason). The rest 1132 patients did not have any abdominal pain after operation. But one case without abdominal pain after ERCP was diagnosed as PEP, and the patient was excluded from no abdominal pain group. Patients’ characteristics between no abdominal pain and non-PEP pain groups were presented in Table 1 .

Treatment and outcomes of patients with non-PEP pain

If the patient presented with post-ERCP cholangitis, empiric antibiotic treatment and etiological examination would be taken. Antipyretic drugs were used if necessary. Patients with mild nonspecific abdominal pain were treated with observation. Analgesic medicine was given when abdominal pain could not relieve spontaneously, or pain intensity was severe. Antispasmodics were used for patients presented with gastric and intestinal spasm. If inappropriate location of nasobiliary tube caused post-ERCP pain, repeat ERCP would be performed to adjust the location of nasobiliary tube. Abdominal pain was relieved in several hours after corresponding treatment.

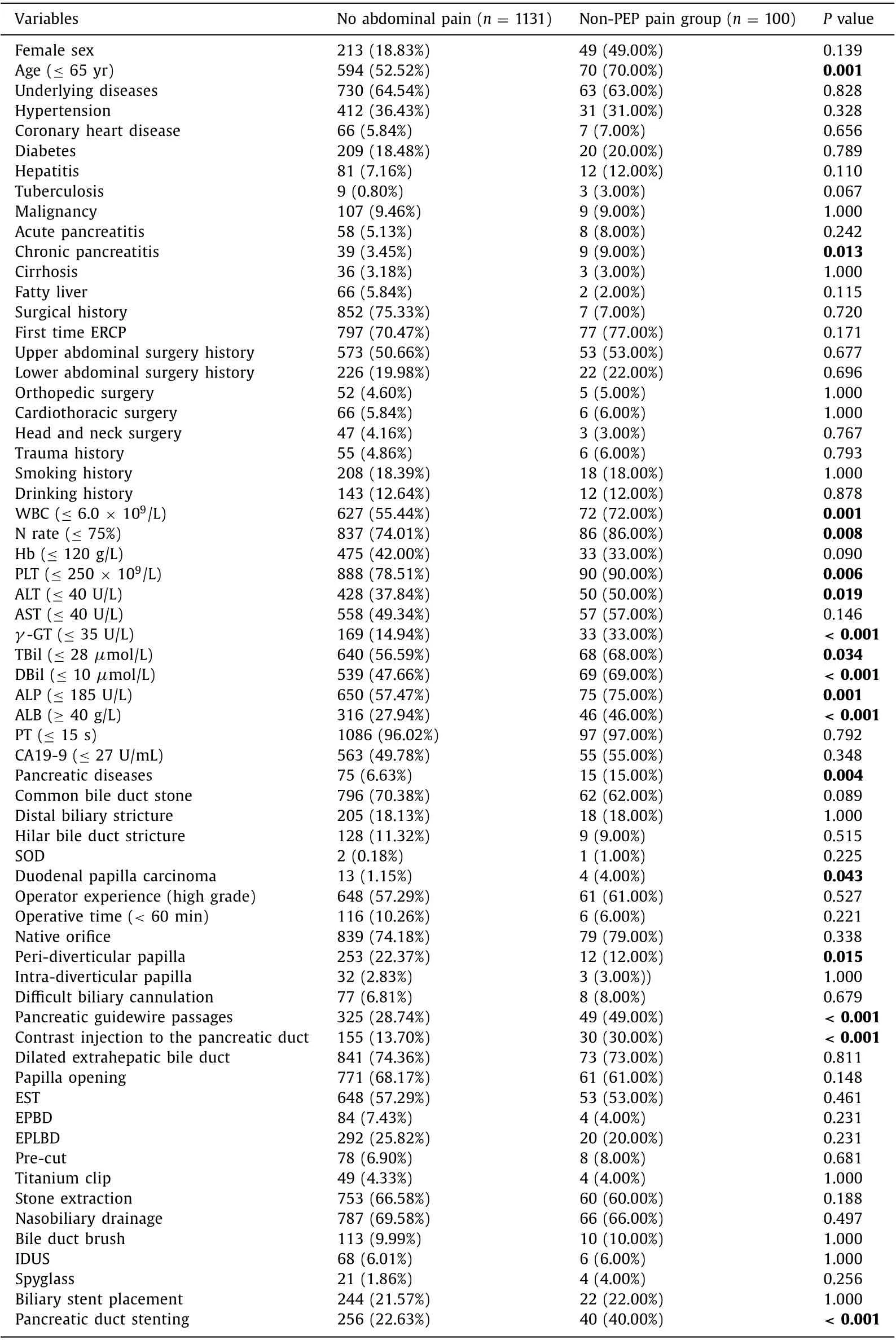

Univariate analysis

In the univariate analysis, 20 of 42 patient-related factors and 5 of 22 procedure-related factors were found to be associated with an increased risk of post-ERCP abdominal pain without PEPand were included into the multivariate logistic regression analysis ( Table 1 ). Patient-related factors included female sex, age ≤65 years, hepatitis, tuberculosis, chronic pancreatitis, fatty liver,white blood cells (WBC) ≤6.0 × 109/L, neutrophils rate ≤75%,hemoglobin (Hb) ≤120 g/L, platelet (PLT) ≤250 × 109/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ≤40 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)≤40 U/L,γ-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT) ≤35 U/L, total bilirubin(TBil) ≤28μmol/L, direct bilirubin (DBil) ≤10μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) ≤185 U/L, albumin ≥40 g/L, diagnosis of pancreatic diseases, no common bile duct stone, and diagnosis of duodenal papilla carcinoma. Procedure-related factors included peridiverticular papilla, pancreatic guidewire passages, contrast injection to the pancreatic duct, no papilla opening and pancreatic duct stenting.

Table 1 Univariate analyses of post-ERCP abdominal pain without PEP.

Fig. 1. Patient flow diagram of post-ERCP abdominal pain. PEP: post-ERCP pancreatitis; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

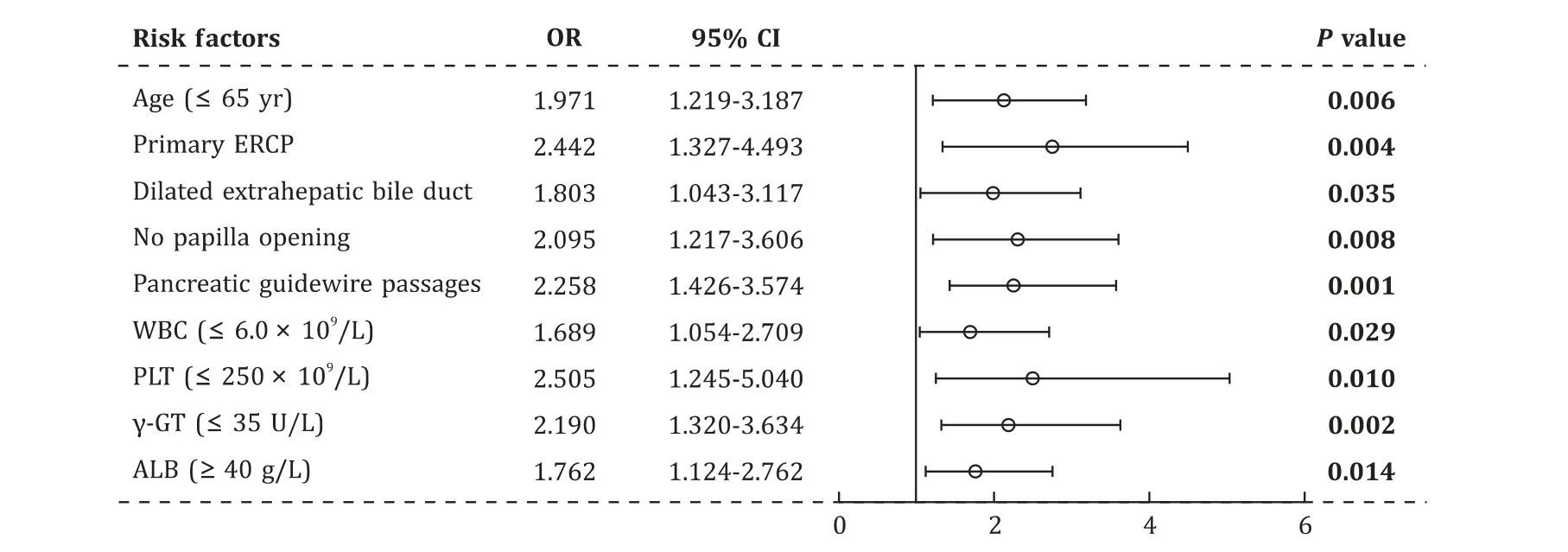

Fig. 2. Forrest plot for the factors of the risk of post-ERCP pain without PEP. ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PEP: post-ERCP pancreatitis; OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; WBC: white blood cells; PLT: platelet; γ-GT: γ-glutamyl transferase; ALB: albumin.

Multivariate analysis

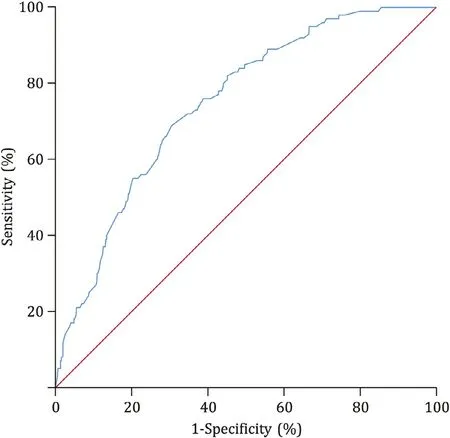

Factors that reachedP<0.15 were used to create the multivariate model. Variables which were considered to be risk factors according to clinical experiences and previous researches were also analyzed. The identified factors were entered into multivariate model ( Fig. 2 ). Nine factors were significant by multivariate analysis, two were patients-related characteristics [age ≤65 years (OR: 1.971), primary ERCP (OR: 2.442)], five were preoperative laboratory and imaging examinations [WBC ≤6.0 × 109/L(OR: 1.689), PLT ≤250 × 109/L (OR: 2.505),γ-GT≤35 U/L(OR: 2.190), albumin ≥40 g/L (OR: 1.762) and dilated extrahepatic bile duct (OR: 1.803)] and two were procedure-related factors[pancreatic guidewire passages (OR: 2.258) and no papilla opening(OR: 2.095)] ( Fig. 2 ). A predictive model was then constructed as follows: Logit (non-PEP pain) = -6.015 + 0.678 × 1 (if: age ≤65 years) + 0.893 × 1 (if: primary ERCP) + 0.524 × 1 (if: WBC ≤6.0 × 109/L) + 0.918 × 1 (if: PLT ≤250 × 109/L) + 0.748 × 1 (if:γ-GT ≤35 U/L) + 0.566 × 1 (if: albumin ≥40 g/L) + 0.590 × 1(if: dilated extrahepatic bile duct) + 0.814 × 1 (if: pancreatic guidewire passages) + 0.739 × 1 (if: no papilla opening).The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was not significant(P= 0.541) at the 0.05 significant level. The highest efficacy was detected when 0.085 was adopted as the cut-off, with a sensitivity of 69.0%, a specificity of 69.5%, and the C-statistic was 0.748( Fig. 3 ).

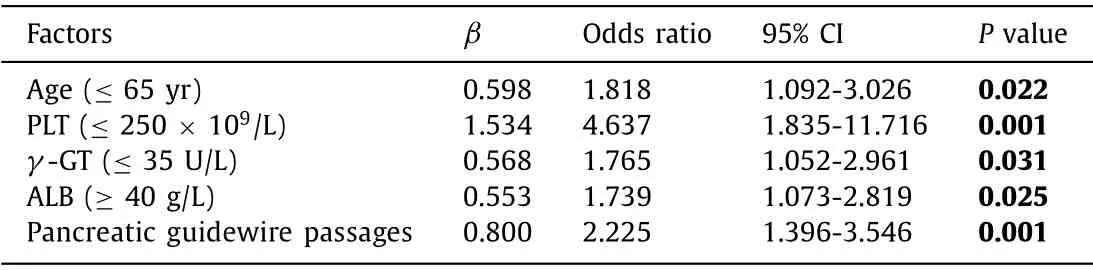

Univariate and multivariate analyses in patients with nonspecific pain

In order to identify factors for nonspecific abdominal pain after ERCP, a subgroup which excluded post-ERCP cholangitis and hemorrhage cases were analyzed. The nonspecific pain subgroup had 84 cases. After univariate and multivariate analyses, age ≤65 years (OR: 1.818), pancreatic guidewire passages (OR: 2.225), PLT ≤250 × 109/L (OR: 4.637),γ-GT≤35 U/L (OR: 1.765) and albumin≥40 g/L (OR: 1.739) were found to be risk factors for nonspecific abdominal pain after ERCP. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was not significant (P= 0.479) at the 0.05 significant level and the C-statistic was 0.723 ( Table 2 ).

Table 2Multivariate analyses in subgroup (C-statistic = 0.723).

Fig. 3. ROC curve for risk of post-ERCP pain without PEP. ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PEP: post-ERCP pancreatitis

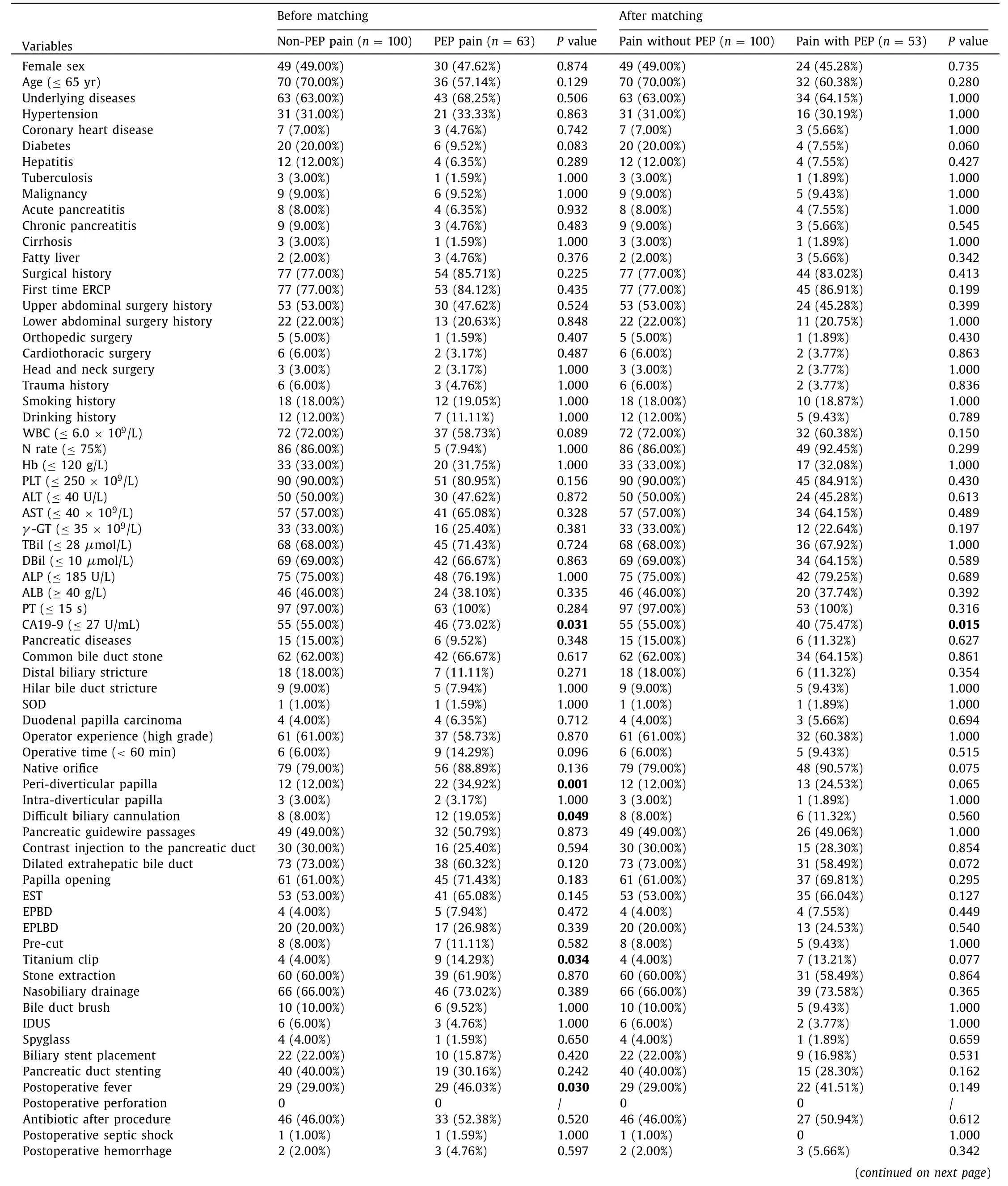

Propensity matching between PEP group and non-PEP pain group

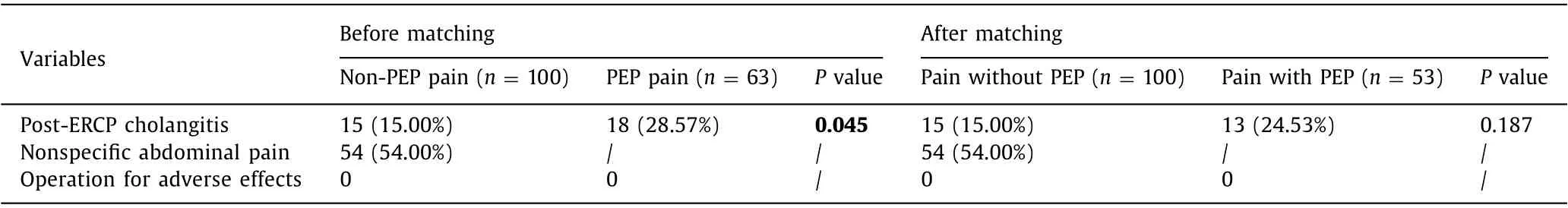

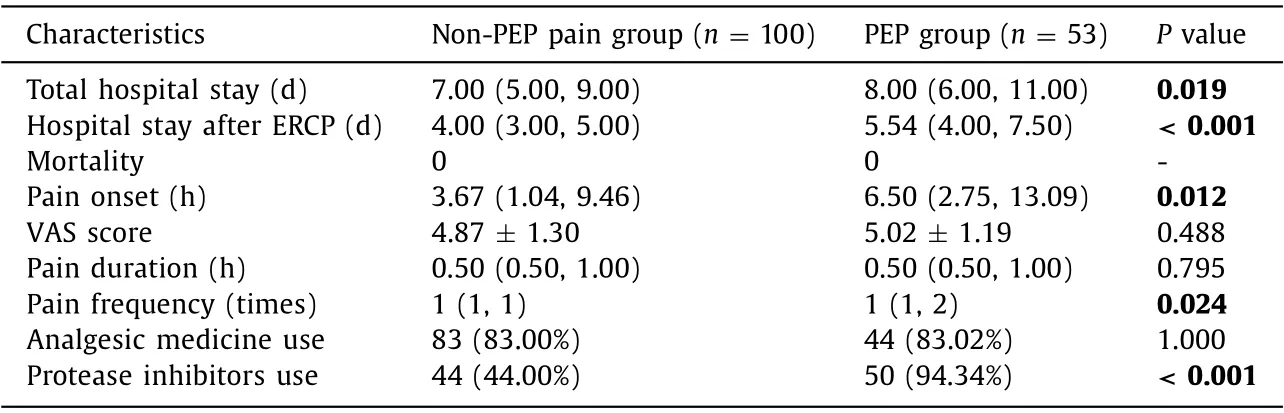

In order to identify the characteristics of post-ERCP pain without PEP, the PEP group and non-PEP pain group were compared and analyzed. Before propensity matching, there were differences between the PEP group and non-PEP pain group in baseline characteristics. Thus, the PEP group and non-PEP pain group were matched on the following variables: peri-diverticular papilla, difficult biliary cannulation and post-ERCP cholangitis with the use of propensity matching. After adjusting potential confounding factors, 53 patients with PEP were matched with 100 patients with non-PEP abdominal pain. The baseline characteristics were comparable after propensity matching except CA19-9 ( Table 3 ). Characteristics between two groups were similar in the pain duration and VAS score (P>0.05) ( Table 4 ). It showed that post-ERCP abdominal pain attacked earlier in the non-PEP pain group than in the PEP group (P= 0.012). The pain frequency of the PEP group was higher than that of the non-PEP pain group (P= 0.024). Patients in the PEP group had longer hospital stay (P= 0.019) and post-procedure hospital stay (P<0.001) than those in the non-PEP pain group. There were no significant differences in the use of analgesic medicine and mortality between the two groups.

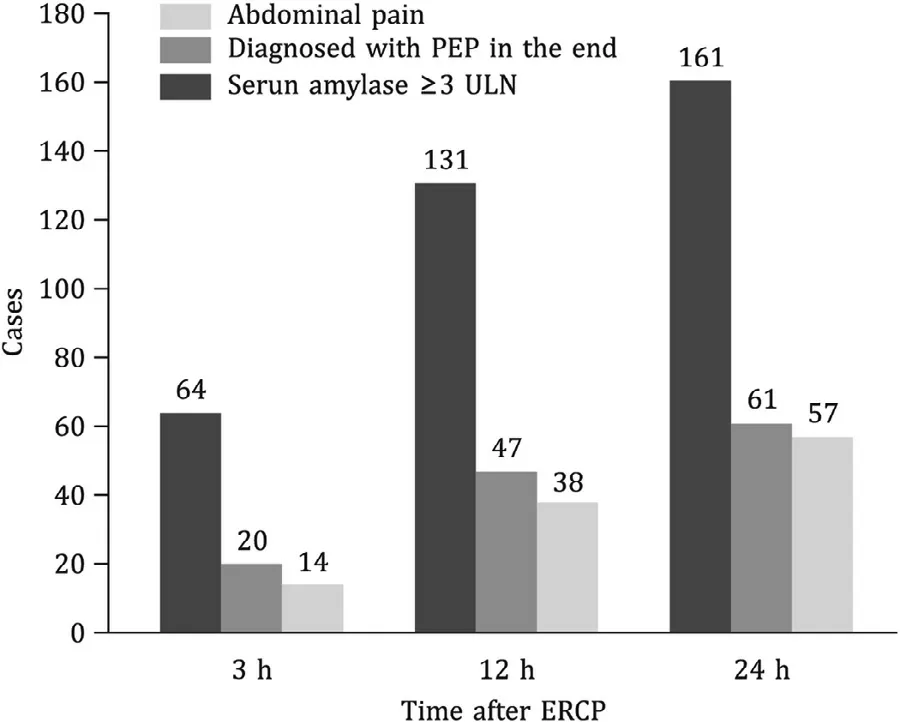

Fig. 4. The parallel relationship between post-ERCP abdominal pain and the diagnosis of PEP. ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PEP: post-ERCP pancreatitis; ULN: upper limit of normal value.

The parallel relationship between post-ERCP abdominal pain and the diagnosis of PEP was analyzed ( Fig. 4 ). In the first 3 h after ERCP, 64 patients presented abdominal pain and 20 of them were diagnosed PEP in the end, but only 14 of them showed an increase in serum amylase level of at least three times greater than the normal upper limit. Between 3 h and 12 h after procedure, another 67 patients presented abdominal pain and 27 of them were diagnosed PEP in the end, but 9 did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria of PEP and needed imaging techniques. After 12 h after procedure, all patients with abdominal pain could be differentiated from PEP. The median time of the pain onset were 3.67 h for the non-PEP pain group and 6.50 h for the PEP group (P= 0.012).

Discussion

Abdominal pain after ERCP is common and is a source of distress to both patient and physician. Occasionally it predicts complications related to the procedure, especially PEP. However, apart from PEP, some post-procedural pain has other etiologies: 1) post-ERCP cholangitis, typically presenting with fever, jaundice, and abdominal pain, which needs antibiotics or repeated ERCP; 2) perforation, manifested as severe abdominal and back pain, abdominal tenderness and fever, which needs intensive management, even surgery; 3) nonspecific pain which is often resolved in several hours. Several reports considered nonspecific pain to be partially related to bowel insufflation [ 5 , 7 ]. According to typical clinical symptoms, it is relatively easier to identify perforation, bleeding and cholangitis. Therefore, it is a challenge for early differentiation between the pain of PEP and nonspecific pain.

Age ≤ 65 years was found to be the risk factor for post-ERCP abdominal pain without PEP in this study. Glomsaker et al. [8] found that younger age was an independent significant risk factor of abdominal pain after ERCP procedure. Though their study did not exclude patients with PEP, the finding was partly in agreement with our result. Peripheral nociceptive function may be attenuated along with growth of age, resulting in decreased pain in some extends [9] .

Table 3 Baseline characteristics and procedure characteristics before and after propensity matching.

Table 3 ( continued )

Table 4 Characteristics between the non-PEP pain group and PEP group after adjusting potential confounding factors.

Patients who underwent ERCP for the first time had a higher risk of abdominal pain after ERCP. Essink-Bot et al. [10] found that patients who had undergone previous endoscopic surveillances for Barrett’s esophagus experienced less discomfort, pain, and overall burden than patients who underwent upper endoscopy for the first time. They suggested that these previous endoscopic surveillances made patients adapt to the procedure.

Dilated extrahepatic bile duct was an independent risk factor of post-ERCP pain without PEP. Persistent dilated extrahepatic bile duct could lead to the decompression of biliary contraction function, resulting in disorder of biliary movements. Biliary infection caused by reflux of duodenal fluid containing bacteria is more likely to occur, even under adequate biliary drainage. And hollow organs are sensitive to both luminal distension and inflammation that cause visceral pain [11] .

Our study confirmed that no papilla opening was a risk factor for non-PEP pain after ERCP. In our study, EST, EPBD and EPLBD were included in the papilla opening. EST and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation could both improve stone removal rate [12] .Endoscopic stone extraction is an effective measure to relieve biliary obstruction, reduce bile duct pressure, and to have adequate drainage [13] . Therefore, no papilla opening may lead to residual stones and inadequate drainage which result in post-ERCP cholangitis.

Pancreatic guidewire passage was also a risk factor of post-ERCP pain without PEP in our study. In all reports of pancreatic guidewire-assisted biliary cannulation, the technique was reserved for use in patients with difficult biliary cannulation [14] . Difficult biliary cannulation may cause more injury and edema at ampullar region, including bile duct, pancreatic duct and papilla, eventually causing post-ERCP pain. Difficult biliary cannulation also indicated long operative time which allowed more gas insufflation resulting in flatulence. A prospective, multicenter study [8] found that guidewire for cannulation predicted moderate to severe pain after ERCP. However, there was no further division of guidewire for cannulation and no possible explanation of this risk factor. Though pancreatic guidewire passage was a risk factor of both post-ERCP pain with PEP and without PEP, potential mechanisms were different and obscure which needed further investigation.

Some preoperative laboratory variables play an important role in the abdominal pain after ERCP without PEP. Lower WBC and PLT before ERCP often indicate severe preoperative infection. Mildly painful or even innocuous stimuli such as gas or passage of fecal material can be exquisitely painful (hyperalgesia/allodynia) when acting on inflamed tissue [ 11 , 15 ]. Thus, even minimally invasive treatment can cause post-ERCP abdominal pain. Moreover, our study found that normal serumγ-GTbefore the procedure was one of risk factors for post-ERCP pain. The effect of serumγ-GThas not been previously investigated. Further studies are needed in the future. Our study suggested that high serum albumin level was a risk factor of post-ERCP abdominal pain. Weiss et al. [16] found that binding of the platelet aggregation inhibitor prostacyclin(PGI2) to albumin prevents its degradation. PGI2 plays a role in the generation of inflammatory and neuropathic pain, and it can induce visceral hypersensitivity [17] . Albumin at 40 mg/mL increased the K D of PGI2 binding to the receptors by 2-3 folds [18] .Accumulation of PGI2 can aggravate postoperative abdominal pain.Albumin, on the other hand, may exert anticoagulant action.Rasmussen et al. [19] showed that albumin decreased coagulation competence and increased hemorrhage during major non-cardiac surgery. However, the detailed relation between high albumin level and post-ERCP abdominal pain needs further investigation.

It is relatively simple to diagnose cholangitis and hemorrhage after ERCP in clinical practice. Therefore, subgroup analysis with the exclusion of post-ERCP cholangitis and hemorrhage cases was conducted. Age ≤65 years, pancreatic guidewire passages, lower PLT, normalγ-GTand elevated albumin were found to be risk factors for nonspecific abdominal pain after ERCP which were the same as those of non-PEP pain. However, risk factors which were presumed to be related to post-ERCP cholangitis discussed above,such as no papilla opening, showed no statistically difference in nonspecific pain subgroup because of the exclusion of cholangitis cases. Most clinicians would agree that patients’ satisfaction was of great importance. Patients’ satisfaction of the ERCP procedure was related to the patients’ experiences of pain during and after the procedure [8] . Nonspecific pain after ERCP may be confusing with early symptom of complications, which influences clinical treatment and causes patients’ postoperative anxiety. After propensityscore matching, we found that the pain onset related to PEP was later than that without PEP [6.50 h (2.75, 13.09) vs. 3.67 h (1.04,9.46),P= 0.012]. Operation-related tissue trauma and visceral traction pain might lead to earlier onset of non-PEP pain. And recurrent abdominal pain was more likely to be found in the PEP group(P= 0.024). Some studies [ 20 , 21 ] showed that strong abdominal pain indicated a high probability of PEP. Hauser et al. [21] found that a threshold VAS score of 5 was strongly associated with the occurrence of PEP. They suggested that the VAS scores for abdominal pain appeared to have an excellent diagnostic value for predicting both the presence and absence of PEP. Thus, VAS score may help distinguish these two types of pain. Significant difference was not found in VAS score (4.87 vs. 5.02;P= 0.488) in our study. Obvious difference may be found in further larger sample sizes studies. For this study, it was reasonable that protease inhibitors were used more frequently in PEP cases. The use of analgesic medicine was similar between the PEP group and the non-PEP pain group.Clinicians tended to give analgesic medicine rather than protease inhibitors to relief pain firstly in our study.

Early abdominal pain after ERCP is difficult to distinguish completely. In this study, serum amylase was tested at 3 h, 12 h and 24 h after procedure. Our study found early occurrence of abdominal pain did not accompany by the elevations in serum amylase levels parallelly, and the differential diagnosis of early abdominal pain was difficult, especially within 12 h after ERCP. Therefore, risk factors detected in this study indicate potential post-ERCP pain, and the characteristics of post-ERCP pain help distinguish PEP pain and non-PEP pain early and provide evidence to perform early intervention.

The limitation of this study is the retrospective nature which might have potential selection and ascertainment bias despite propensity-score matching.

In conclusion, our study indicated that age ≤65 years, primary ERCP, dilated extrahepatic bile duct, no papilla opening, pancreatic guidewire passages, lower WBC, lower PLT, normalγ-GTand elevated albumin were independent risk factors for post-ERCP abdominal pain without PEP. Characteristics of post-ERCP pain were different in pain onset and frequency between PEP patients and non-PEP pain patients. Abdominal pain attacks earlier and occurs with a lower frequency in non-PEP patients. These findings could predict potential pain after ERCP and help patients make full psychological preparation for postoperative pain, which may reduce the psychological and financial burden of patients and therefore improve the quality of ERCP procedures and patient management.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Meng-Jie Chen: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis,Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review& editing. Ru-Hua Zheng: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Jun Cao: Data curation. Yu-Ling Yao: Data curation. Lei Wang: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - review& editing. Xiao-Ping Zou: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition,Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing - review &editing.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871947).

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee at Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Drum Tower Clinical Medical College.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Surgical exploration with non-resection in the setting of resectable,borderline and locally advanced pancreatic cancer

- On-table hepatopancreatobiliary surgical consults for difficult cholecystectomies: A 7-year audit

- Preoperative lymphocyte to C-reactive protein ratio as a new prognostic indicator in patients with resectable gallbladder cancer

- Prognostic potential of the small GTPase Ran and its methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Relief of jaundice in malignant biliary obstruction: When should we consider endoscopic ultrasonography-guided hepaticogastrostomy as an option?

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International