State of the Art

2022-04-17

Just 20 years in the making, China’s contemporary art scene is a fresh canvas. Without the entrenched stability that comes from decades-old institutions and networks in the West, and a population without much art education or familiarity with exhibition culture, China’s creators and curators experiment free from the excess baggage of past ideas and tastes. Artists have dipped their brushes into social media trends, turning their works into viral short-videos, while art museums walk the fine line between educating the public and enticing young visitors eager for photogenic snapshots. Meanwhile, art NFTs from Chinese creators are popping up (both legally and illegally) online, tapping into the global craze but making regulators nervous. Beyond the city sprawl, art communes and installations struggle to use their creativity to fuel rural revitalization. In this issue’s cover story, we investigate the many sides to China’s burgeoning art scenes, and find a picture that is colorful and sometimes kitsch.

當艺术不再“高冷”,美术馆成了拍照打卡胜地,青年中产爱上“潮流艺术”收藏,NFT艺术崭露头角。都市之外,艺术家用创造力在乡村探索新的可能性。当代艺术正在悄悄进入我们的生活。

Illustration and Design by Cai Tao and FengzhengYisheng

Photography by Nicoco Chan and Yukai Peng (彭昱凯)

Additional photographs from VCG

Photo Shop

Museums in China increasingly rely on social media to bring in visitors, but is there a cost to going viral?

“Be casual,” a security guard in a video on Xiaohongshu tells the glamourously swathed young woman in black dress and sunglasses. He leans against the slate-smooth, off-white concrete wall, tilting his head back to demonstrate the perfect pose. “Now, turn around and put your hand over there,” he advises while she walks over to follow his lead. “Oh, beautiful!”

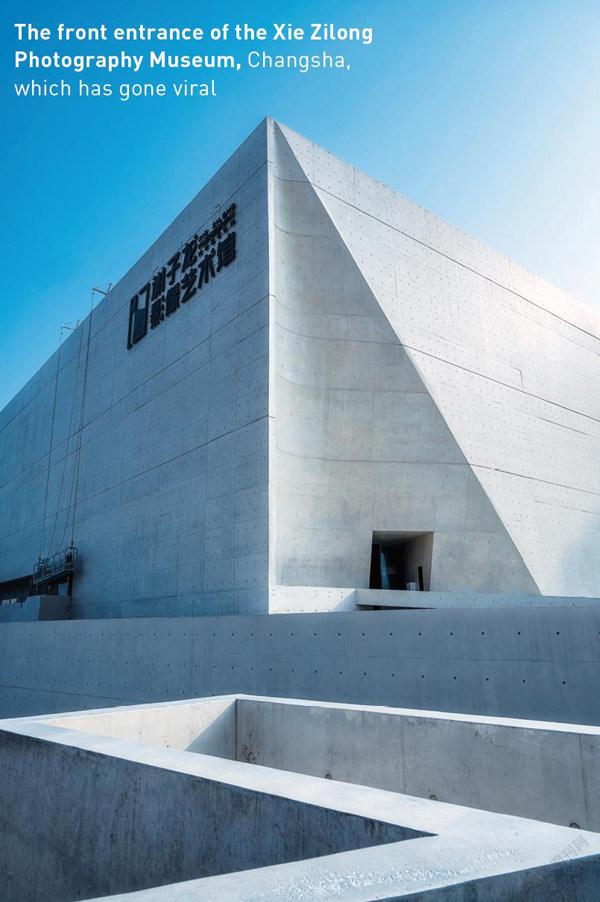

On hot sunny days over summer last year, two lines of phone-swiping millennials snaked 15 meters down a ramp leading to the cave-like entrance of the XieZilong Photography Museum in Changsha, Hunan province. They weren’t queueing to get exhibition tickets (as TWOC mistakenly thought), but to get selfies on two ledges built either side of the front door: lounging with the gray sky behind them, later editing in a background of a sunset or blue sky before posting it on social media app Xiaohongshu (RED).

Many snappers seem to be tourists, as a lot of social media accounts “checking in (打卡)” at this location are registered to major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, or Guangzhou. By March this year queues had stretched to an hour’s wait, according to review app Dianping. The museum’s review page is still flooded with discussions of how nice the museum coffee shop is, or wonders at why this cavernous entrance, and its friendly posing security guard, had gone viral.

Today, most respectable art museums in China engage in a balancing act, both trying to profit from viral trends and provide art education to the public (or at least make it more accessible). But that involves catering to what the public wants, which can be vastly different from the high-brow gallery tradition.

“Young people all like beautiful photos…somehow the art museums became an option,” says Xiang Yejing, a 27-year-old Shanghai-based supermodel. Xiang is a regular visitor to art exhibitions, dressing up specially and taking between five and ten photos per exhibition. These photos are a blend of her and the artwork, and she uploads them to her 2.5 million followers on the microblogging site Weibo, 236,000 followers on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), and 238,000 on Xiaohongshu. “My friends tell me that they go to art exhibitions because they want to take photos.”

The same phenomenon is evident at 798, a popular visual art zone in Beijing. On a weekend in early March, a queue wound round the block for Galleria Continua’s latest show, where artist Giovanni Ozzola creates a giant floor-to-ceiling picture in the space, of the sea around Spain’s Canary Islands. Four and five-star reviews on Dianping enthuse about how beautiful it is to have your pictures taken at this free exhibition, pretending you are by the sea.

Next door, at the M Woods 798 annex, is an exhibition of American artist Austin Lee, whose scruffily-drawn, vibrantly-colored CGI doodles are displayed in a brightly-colored space full of photo-takers. “I really like the strong contrast in colors,” says a woman in a stylish dress and handbag, who had found out about the exhibition via Xiaohongshu. “It’s very childlike.” “Douyin told us to come,” says another woman in a gray-pleated skirt, reviewing her boyfriend’s photos of her.

Although art museums across the world are reckoning with influencers and Instagram, in China it’s arguably accelerated and more obvious. The relatively late establishment of private galleries since the 1990s means older generations did not grow up in a culture of visiting art museums and rarely go even now, so that young people make up the demographic that curators are trying to woo. “For all the museums, especially the non-profit ones, the way they earn money is through selling tickets,” says Xiang.

The vast majority of China’s population now access information and tips on places to visit through a gaggle of social media apps, many of which reward businesses as well as users for generating traffic. Dianping, for example, gives users exclusive offers if they have been registered for over three months and published four reviews of over 100 words. Positive user reviews and ratings vault the business higher up on Dianping’s lists of recommended places, boosting its visitor numbers or ticket sales. The same can be said for Douyin—the greater the number of likes and comments on a video, the more it is recommended to people.

Enter the Key Opinion Leader, or KOL, social media influencers in particular fields. Depending on the field, they may have just 5,000 followers or several million. Like Western influencers, they regularly recommend products or tourist destinations to their fans. “You really rely on the power of the KOL to boost your visibility online now,” says Rory Mencin, a Chengdu-based freelance art curator.

TWOC confirmed with representatives in art museums from Hangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing that their institutions privately message KOLs, offering free tickets in return for a visit and some snaps of the artwork in their social media accounts. “It’s free advertisement,” says Xiang. Her posts can reach a wide audience—one on Douyin about a Joan Cornellà exhibition at the HOW Art Museum in Shanghai was viewed 32,000 times.

Mencin also says it’s common for smaller museums to pay KOLs to attend. In fact, he cites the inability of a Chengdu gallery space to pay KOLs to attend a recent exhibition he co-curated with his wife, Tracy Lee Mencin, for a swift decline in visitor numbers after opening—he estimates it halved in two weeks. “If you can pay people to generate hype, then your exhibition will be more successful and it doesn’t matter so much about the merit of the exhibition.”

Many art museums across the country have embraced social media marketing strategies to varying degrees in order to go viral. To promote an exhibition on Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing (which has a target audience of 25-to-35-year-olds) challenged Douyin users to video themselves “Killing a Banana” (based on Cattelan’s most famous piece of an ordinary banana gaffer-taped to a wall), and gained 100 million impressions on the app. “We thought it might go viral on a short video platform,” says DanyuXu, deputy director of communications at UCCA, “because you don’t really need a lot of artistic background to create a video about a banana.”

Visual arts education in China has historically been limited. Xiang, who studied art history in university, remembers only having one 40-minute class per week for art growing up in her elementary and middle school in Hangzhou, with little focus on art history. “We needed to focus on the [examination] scores and those don’t include art.” She remembers one of her followers saying to her that she didn’t go to art museums because she was “afraid” of art.

Censorship can also make it more challenging to stage unconventional or thematically complex exhibitions. China’s Museum Regulations, approved by the State Council in 2015, require the content of museum exhibitions be approved by local government culture departments, and must promote socialist agendas, such as “popularizing scientific knowledge” and “promoting social harmony.” A piece at UCCA’s Cattelan exhibition, originally entitled “Him” and featuring Adolf Hitler as a child kneeling in prayer, was retitled “No” for the exhibition, with a paper bag placed over Hitler’s head.

Some art museums which have more of a reputation for high-brow art, including public museums, have embraced trends to various degrees. Beijing’s Red Brick Art Museum, a private institution which Dianping users praise for its photogenic red brick architecture (but criticize for 140 yuan ticket prices), has also focused on featuring artists who are more interactive, such as OlafurEliasson, a well-known Scandinavian artist whose installations fashioned out of natural phenomena are both photogenic and immersive. The National Museum of China launched an “immersive” Van Gogh exhibition in summer 2019 with no physical paintings, but projected animations instead.

Not everyone in the art world is on board with these strategies. “I think this trend isn’t good,” says Huang Wenlong, an assistant curator at Beijing’s Inside-Out Art Museum. “In general, it weakens the function of art museums and makes them places for entertainment.” She says her museum does not want to become , but is open to having KOLs promote their exhibitions—only stopped by a lack of staff to arrange this. “Some museums have several positions dedicated to [KOL outreach].”

Others hope trendy exhibitions can introduce traditional gallery culture to netizens. In 2019, Xiang set up an account each on Xiaohongshu and Instagram dedicated to art education, as she was shocked at her followers not knowing of CaiGuoqiang, a major Chinese artist specializing in using fireworks whose work was featured in the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony.

On these accounts, which are separate from her personal accounts, she gives recommendations of exhibitions worth seeing (including those with niche or challenging content), livestreamed art lectures from a gallery, and lengthy descriptions of the artist and art movement beneath photos of artworks. She hopes these will broaden her followers’ exposure to visual art and artistic education.

But these posts are the exception in KOL interactions with visual art, rather than the norm. Xiang’s personal account, where posts about exhibitions are few and superficial, has nearly 238,000 followers, compared to the 10,000 followers on her educational account. Xiang believes she won’t really change popular attitudes to art unless a bigger group of KOLs start doing the same thing: “You can’t really change people’s interests directly from beauty to art.”

China is experiencing a museum-building boom. Exact figures vary, but the National Bureau of Statistics totted up 1,600 new institutions established between 2015 and 2020. Real estate companies like to build art and history museums for tax rewards, creating phenomena like the Unicorn Star Art Museum, a privately owned chain with outlets in at least 15 major Chinese cities, usually in shopping malls. Local governments welcome these museum-building projects to meet their cultural development targets—even if they lack artworks or artifacts to exhibit.

Physical interaction, in the form of photo areas or the selection of engaging visual artists, is more and more important even in serious art institutions. The Today Art Museum in Beijing ran an exhibition last year on Japanese animation artist Hayao Miyazaki (with weekend tickets at 128 yuan a pop) that Mencin says comprised mainly selfie zones, focusing on “moving animatronic characters and plastic, painted set pieces.” This is exacerbated in cities where there is a weaker presence for art museums—in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province with a “less developed” art scene according to Mencin, there is a more commercial element to museum culture, making selfie zones an integral part of the process.

This was what he and Tracy Lee Mencin realized when they co-curated their exhibition in Chengdu, which focused on American and Chinese street art in the city. Although the exhibition tackled a serious subject, and was laid out in a traditional gallery fashion, they added special featured areas—graffitied backdrops looking like a shuttered American side-street, and later an artist’s studio and a mock-up of a New York subway car when the exhibition moved to a mall in Shanghai—to cater to visitor demand. He says the Shanghai venue also paid KOLs to attend.

The Shanghai mall, a relatively new build at only sixth months old, “had a greater hand and interest in keeping visitor numbers up,” says Rory Mencin. “For an [established] museum they don’t need to because they have an institution…but there are [new] museums popping up all the time, and they definitely need exposure.” Or, perhaps, just a security guard with an eye for what makes a good selfie. – Alex Colville

A visually striking exhibitionof Shiota Chiharu at Long Art Museum, Shanghai, has gone viral on Xiaohongshu

American artist Austin Lee attracts with bright colors at M Woods 798, Beijing

The front entrance of the XieZilong Photography Museum, Changsha, which has gone viral

A visitor takes a photo of Maurizio Cattelan’s viral banana art “Comedian” during his exhibition in Beijing’s UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in 2021

A visitor to Beijing's branch of the Unicorn Star Art Museum, livestreaming the experience to followers

Art in the Field

Art festivals try to bring visual culture to China’s villages, but are they being put to good use?

For centuries, the sprawling terraced fields above Hanxi village, Fuliang county, had nurtured the highland region’s famous black tea: “The merchant cared more for money than for me, one month ago he travelled to Fuliang to purchase tea,” goes the poem “The Pipa Player” by BaiJuyi (白居易) in the ninth century, describing the attractions of the tea from the viewpoint of the merchant’s wife.

Yet in May of 2021, Hanxi’s tea terraces had new company—a huge lantern-like installation standing at the top of the hill made of see-through fabric. By daytime you could see the tree encased within it, while lighting up with ambulating contours at night.

This is , created by Chinese architect Ma Yansong and inspired by Fuliang’s mountainous landscape. Located outside China’s porcelain capital of Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, Fuliang was once where artisans gathered in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279) to produce porcelain directly for the emperor’s stores. But today, artists, architects, and musicians are flocking here under a different sort of invitation: to turn Fuliang’s unremarkable village buildings, abandoned warehouses, barren land, and empty tea gardens into an open-air gallery.

Art at Fuliang, the first Chinese edition of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Field Triennale festival, began in May of 2021 with 26 artists from five different countries invited to give new life to Fuliang’s landscape and cultural heritage. Deploying local resources and workers, even turning locals’ stories into visual exhibits, the artists completed 22 projects that drew in around 50,000 visitors in May last year, and tried to create a new model for rural revitalization.

Like the countryside of Japan’s Niigata prefecture, which began the Art Field Triennale in 2000 to bring visitors to its aging and natural-disaster stricken villages, China’s rural regions face similar problems of depopulation, poverty, and environmental degradation. A massive flow of labor from the countryside to the cities has deprived villages of young life and economic opportunity, while pollution and construction have degraded the natural environment.

Curator and educator Zuo Jing, however, tells TWOC that projects like Art at Fuliang should not be categorized as “rural art” per se—“there’s no such concept”—but rather, “rural reconstruction through culture and art.” The basic idea is “to participate in the development of the countryside from the perspective of culture and art, to emphasize the creative power of art to bring sustainable development, increase locals’ consciousness, as well as pride and happiness,” he explains.

In 2011, Zuo launched the Bishan Village Project in Anhui province with his friend, filmmaker OuNing, which saw the conversion of a disused ancestral hall into a bookshop café, the opening of chic guesthouses, and a collaboration with designers to launch community-branded stationery and apparel to secure ongoing funds and create a marketable identity for the village. This was followed by projects in Guizhou, Yunnan, and Henan provinces. In each, Zuo collaborated with professionals such as architects, painters, photographers, sculptors, and dancers to develop conservation projects, workshops, exhibitions, and festivals according to local resources and needs.

Dozens of art festivals take place in villages around China today, and rural governments have invited private institutions or individual artists to open up art projects, art schools, and rural residency programs. They will often offer abandoned village homes and schools as places that artists can live and work in, transform into businesses, or even turn into installations. The biennial Heshun International Art Festival in Xucun village, Shanxi province, has been held every two years since 2011, and claims to attract tens of thousands of visitors to boost businesses, fill up village homestays, and buy local handicrafts.

Locals were encouraged to join Arts at Fuliang. “Six out of 50 volunteers were locals from this village in November,” TengHuimin, head of the festival’s local working group, tells of the event’s second edition in the fall of last year. “Some eloquent volunteers are trained to introduce the artwork [to tourists], while the rest took charge behind the scenes by selling local products, guarding the entrance, checking visitors’ health codes, and more.”

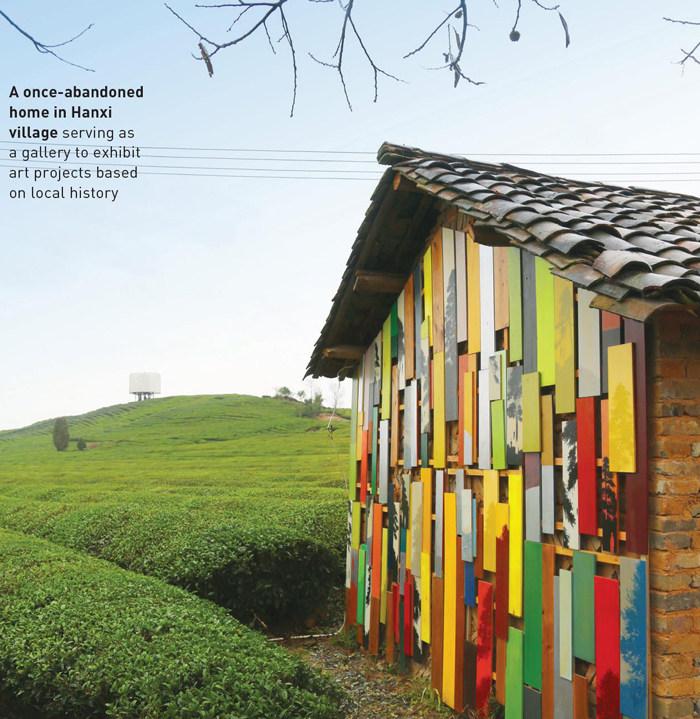

In Hanxi village, the first stop for festival visitors are two abandoned houses that served as the canvas for by artist Xiang Yang, who has exhibited at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York and National Art Museum in Beijing. Xiang and local villagers renovated the roofs of the houses together and repainted the walls 16 times with different colors with the idea of showing layers of history. Xiang also collected past and present images of Shiziyuan—people washing clothes by a stream, chickens chasing each other—and carved those scenes onto the walls, collecting the peeled-off paint scraps and lacquer in a small transparent bag posted under each relief.

Inside one of the homes, visitors can see the process of ceramic-making from a screen inside the cooking stove. In another house, QianChangxian, a 50-year-old local volunteer guide, bursts into tears while describing to visitors in a dim room filled with dazzling rose-red painted jars. Artist Wu Jian’an had collected these ordinary jars for storing pickles, water, and rice from villagers, and arranged them on the walls and ceiling, showering the rustic dwelling in bright pink.

Most of the villagers in Hanxi are immigrants from Chun’an, Zhejiang province, who moved here in 1957 when the construction of the Xin’an River Hydropower Station flooded their homes. They had brought these jars, and little else, as they travelled nearly 300 kilometers by foot to settle in what was then an uncultivated part of Fuliang. Qian was born here to immigrant parents from Chun’an, and says her neighbors used the pickle jars to make a paste of mashed fermented soybeans, chili, and salt that they called “immigration sauce.” “When I was in elementary school, I ate rice mixed with this sauce for three years, no other dishes at all,” she recalls. “That’s what extreme poverty is.”

But not all rural artistic renovations run smoothly, as , a reality TV show which invited urban professionals to redesign homes for people in the China’s rural villages, found out. During the show’s eighth season in November 2021, a rural property owner from Gansu province accused architect Tao Lei of disregarding his wishes and leaving his family with a 1.3 million yuan (200,000 US dollars) price tag for a home they did not like. Combining wood panels with cement and red bricks, Tao adopted a minimalist design that fit his interpretation of local aesthetics, but the homeowner viewed exposed bricks as a sign of poverty, and preferred a two-story European-style villa like his neighbors had: with columns, balconies, and ceramic tiles for the exterior walls.

Local governments also sometimes need convincing. In 2016, the central government issued a statement to close the Bishan commune, saying the project was not “politically correct” as the local party committee’s leadership was not apparent. However, when the central government proposed rural vitalization as a key national policy in 2017, rural administrators across the country began to enthusiastically push for similar projects.

This has sometimes led to over-development and projects which critics argue have little to do with local culture, or bring few direct benefits to locals. After residents of Xiaoruo “Rainbow Village” in Wenling, Zhejiang province, painted their seaside homes a variety of pastel colors to attract lifestyle bloggers and trendy businesses, an investigation by TWOC last year found that rising property prices had created rifts between formerly close-knit neighbors in the village. Most of the profits also went to business-savvy outsiders, though the project at least brought more young locals back to the village.

Li Yaying, CEO of a tourism company contracted to create boutique homestays, cafes, and libraries out of old village dwellings, also describes “cognitive asymmetries” between her team and the local government. Local administrators were not confident that her project in Dongyang village, western Jiangxi province, would succeed, so they withheld supplies and infrastructural support.

“Imagine rebuilding houses with no water and electricity,” Li recalls. “I was so desperate, we asked the locals to use their residential power, but our high-capacity machines caused power outrages which delayed the project.” Not until the businesses started operating did the government connect them to water pipelines and roads.

On some level, Zuo admits that “rural reconstruction through art” has moved away from art for art’s sake. “In the beginning, we wanted to bring artistic resources from the city, but after so many years, at least in my experience, it’s no longer as important…[as] design,” he says, pointing to the design of buildings, landscapes, and products as the new keywords of his work.

“This is not to negate the use of art,” he adds, pointing out the role of artwork and festivals in giving locals a cultural education and a visual identity they can be proud of. “Art might not be the only solution to the development of rural areas, but it could undoubtedly establish dialogue and build a link with the outside world.” – Zheng Yiwen (鄭怡雯)

A once-abandoned home in Hanxi village serving as a gallery to exhibit art projects based on local history

Artist Wu Jian’an painted old jars from villagers rose-red and arranged them on the walls and ceiling in “Memory Containers”

A group of artists wrapped red cloth over the Ziquejie rice terraces in “Land’s Pulse,” part of an art festival in Hunan province in 2015

A Token Project

Can NFT art flourish in China?

By day, Eminem Guo is a worker at a state-owned enterprise in Shenzhen. But after hours, he’s selling on a black market. Together with other anonymous Chinese internet users, “Kelly” and “Marktim,” they set up “Tiger Club,” an account selling digital art as Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) on sales platform OpenSea.

Although technically banned in China, there is huge interest in the country over NFTs: Chinese servers dominated global Google searches on NFTs in 2021 according to Google Trends. Some are tapping into the action covertly, seeking untold riches potentially just a VPN away.

NFTs are a complicated subject—in a nutshell, they are usually a digital image that is assigned value by being unique. They can be traded digitally, as long as they are attached to a cryptocurrency, like Ethereum (ETH) or Bitcoin, which keep records of all exchanges to guarantee against fraud or forgery.

But although there are many applications for NFTs, they are mostly associated with expensive digital artwork, both in China and globally. This can largely be ascribed to the jaw-dropping 69 million US dollars price set at Christie’s auction last year for an NFT titled by digital artist Beeple, as well as the nearly ubiquitous collection of “Bored Ape” and “CryptoPunk” avatars, which have fetched astronomical sums as more and more celebrities buy and use them as profile pictures.

Guo (who did not want to share his real name with TWOC) bought his first NFT in December 2020, but was inspired to get involved with creating and selling them when one of his favorite actors, Shawn Yue, sold his profile picture on social media as an NFT for over 5.9 million US dollars at a Christie’s auction in Hong Kong in September 2021.

The Tiger Club NFTs are anime portraits of an exasperated-looking tiger. These cartoon portraits of animals, each only slightly unique in color, character, and style from one another, echo famous NFT collections from the West.

That’s not accidental. Like many other young Chinese creators, Guo and his cohort are influenced by “the fashion of the times,” as he claims, and have chosen to emulate this by outfitting their tigers with a variety of up-to-date outfits, hats, glasses, necklaces, and other mix-and-match accessories, which they manually paint on their computer before uploading to OpenSea. That means they only have 26 images on their account, whereas their inspirations, the Bored Ape Yacht Club and CryptoPunks, use AI to create tens of thousands.

Although the aesthetic of Tiger Club may not be totally original, they’ve still made Guo a millionaire—sort of. The money he has made is illegal in China: The People’s Bank of China outlawed domestic trading of cryptocurrencies in 2017 due to the risks of rampant speculation and the lack of centralized control. Chinese traders could still trade on foreign platforms until the NFT boom last year spooked regulators.

In October 2021, at a convention on NFTs, three of China’s largest internet companies (Alibaba’s Ant Group, Tencent, and JD.com) reaffirmed their commitment to keep NFTs away from cryptocurrency by linking them to the yuan. This allows them to continue trading NFTs, referred to as “digital collectibles.”

The trade in digital collectibles in China is now more centralized. To trade on Chinese e-commerce or blockchain platforms, users must upload their phone and ID number, and only pay in yuan. They cannot exchange or resell for 180 days after purchasing, to curb speculation.

Guo views the measures as ineffective for those who are already involved in NFT trading, as he has sold two of his works for 36 ETH each (about 1.2 million yuan at the time of writing). “If you really want to sell you can do an underhand trade,” he says. He thinks the regulations are "pointless," as all they do is force creators to keep their digital assets online when it could be circulated back into China.

This also prevents potential artists from sharing their work with domestic audiences when there’s much more money to be made elsewhere. “Of course, I would rather sell my artwork in China. I actually believe the entrepreneurial environment and potential for artists is somewhat better here,” Guo claims. He suggests China needs its own version of OpenSea, with more freedom to buy and sell. “Then we can move forward as artists.”

But regulations haven’t deterred others: 27-year-old freelance artist Song Ting has attracted attention with her psychedelic digital collectibles based on traditional Chinese artwork like the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu province. In the past year, she has partnered with Tencent and KFC, and seen one piece sell for 667,000 yuan. The system will likely encourage those who work within it.

– Rory Mencin

Full disclosure: Rory Mencin is an art curator sourcing Chinese NFT artists for the international market.

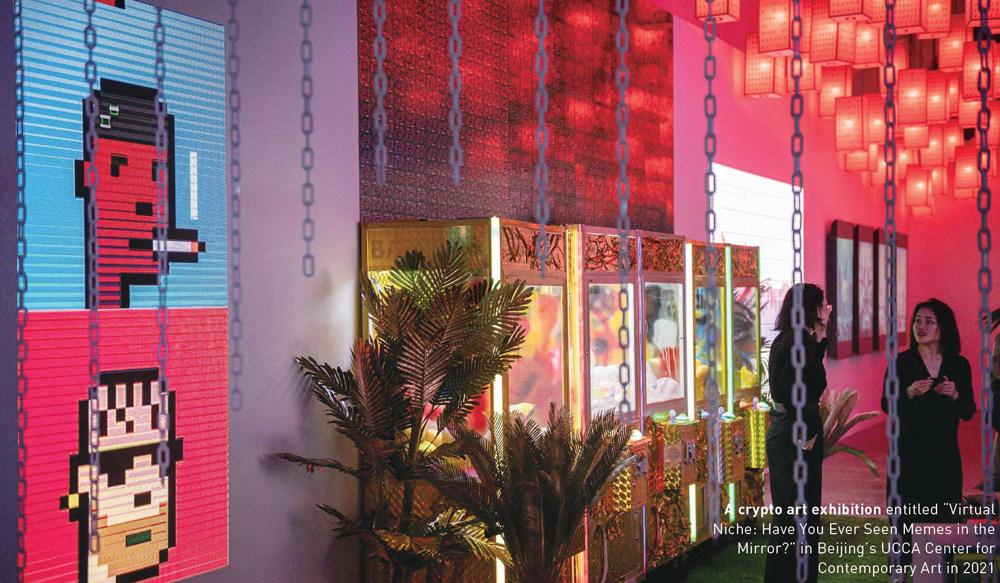

A crypto art exhibition entitled “Virtual Niche: Have You Ever Seen Memes in the Mirror?” in Beijing’s UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in 2021

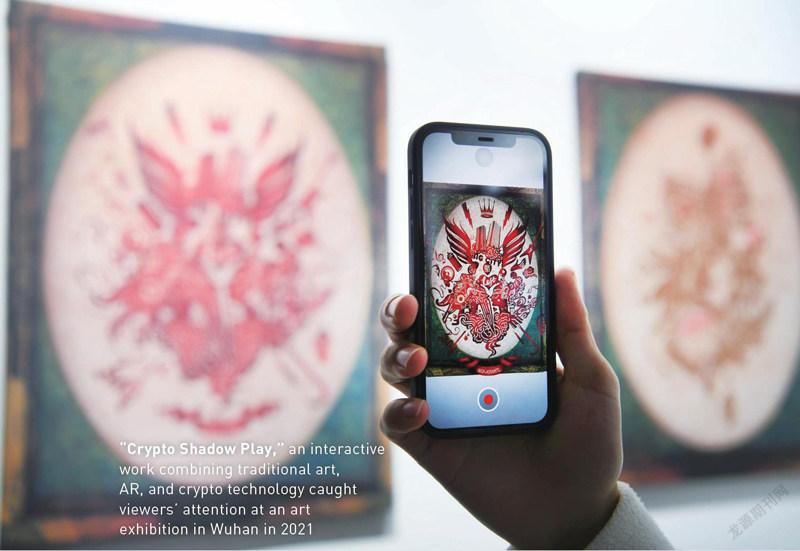

“Crypto Shadow Play,” an interactive work combining traditional art, AR, and crypto technology caught viewers’ attention at an art exhibition in Wuhan in 2021

Collecting Tends

Young, middle class buyers are bending China’s art market to their own tastes

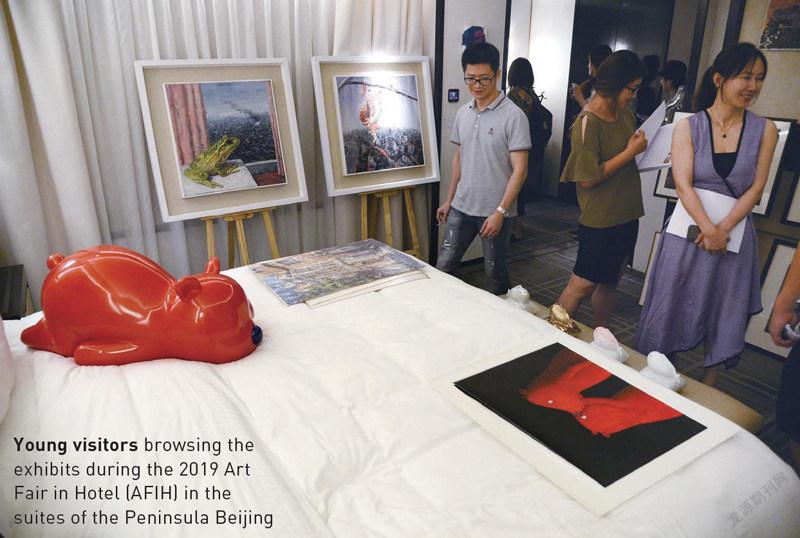

Every summer, the fifth floor at the five-star Peninsula Hotel in the heart of Beijing transforms for a weekend-long extravaganza. A few dozen suites open their doors to visitors who walk in to discover colorful diptychs above headboards, abstract sculptures on window sills, glittering jewelry in drawers, and ceramic figurines by bathtubs, all curated by galleries who temporarily occupy these suites as their booths at Art Fair in Hotel (AFIH).

Unlike most art fairs, where galleries promote and sell their works inside convention centers, “AFIH feels more approachable,” Wang Di, a visitor, tells TWOC, “Although there are expensive items, the overall vibe is more like hawkers selling paintings.” While some price tags show a longer string of zeros, the fair has a wide selection of items priced between a few hundred to a few thousand yuan, affordable to those who might not want to spend more than a fraction of their monthly income on these works.

According to AFIH’s survey in 2021, 55 percent of the fair’s visitors identify themselves as white collar workers, part of a rapidly growing demographic of middle-income individuals who now make up 30 to slightly over 50 percent of China’s population, according to various definitions including from China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

These individuals, who earn 500,000 yuan (80,000 US dollars) per year, are largely urban, past worrying about necessities, and tend to have funds for non-essential spending such as travel, entertainment—and now art. While they might not be striking headline-making bids at art auctions, they are slowly forcing the art market to adapt to their demands.

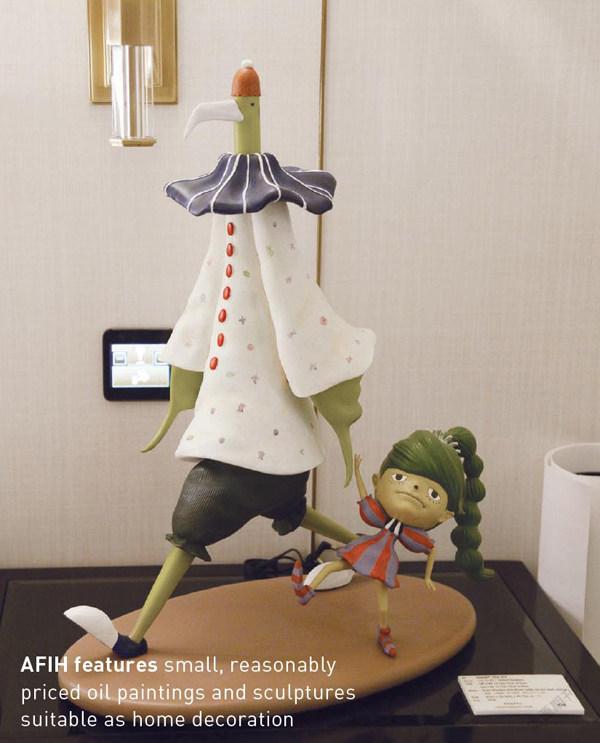

Once a novelty, art fairs have mushroomed in China, and galleries are adopting strategies to cater to newcomers. Dayu Yang, Founder of Beijing gallery PIFO, told Artsy, an online art trading platform, that the gallery made an effort to bring small-scale works to Art021 Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair, including a painting that sold for 4,000 yuan (about 650 US dollars).

For admirers of big-name artists, economic alternatives exist. For those who can’t afford original works by the Chinese-French painter Sanyu (1901 – 1966), whose oil painting sold for more than 170 million Hong Kong dollars (about 22 million US dollars) at a 2020 auction, prints of Sanyu’s works are sold at art fairs for 10,000 to 50,000 yuan (1,500 to 8,000 US dollars). These licensed, high-quality reproductions of paintings satisfy collectors’ need for both originality and scarcity. “A lot of living artists now accept this form. So do galleries, which might help [painters] find good printing studios to work with,” says Ashley Qin, an employee of an online art trading platform.

However, some differences of opinion still exist. “In the West, prints are a [widely accepted] form of art,” XuMengchen, an independent art advisor, tells TWOC, “whereas in China some [buyers] might associate prints with [cheap] replicas and have stereotypes against them.”

One of the most popular sections in auctions nowadays, “trend art (潮流藝术),” also contributes to the rise of the middle-income market. A classification coined in China, the term “trend art” has no exact definition, but encompasses a wide range of artworks and artists, usually colorful, bold, and figurative. Works that found their way into this section include Japanese artist Takashi Murakami’s kaleidoscopic murals of smiley faces and American designer Kaws’s clown-like figures.

In an interview with Hi Art magazine, art collector and critic Mao Zhuang summarized a few features of trend art: The artists incorporate pop-culture elements into their works, interact frequently with fans on social media, and collaborate with trendy brands to produce merchandise. The merchandising aspect is further blurring the boundary between trend art and consumer goods: If Daniel Arsham’s plaster sneaker sculptures and Jeff Koons’s balloon dogs have a place in museums, then there are good reasons to count Adidas x Arsham sneakers and miniature balloon dog pendants as artworks, too.

Other partitions are slowly dissolving as well, spurred by the pandemic and the expanding clientele. Traditionally, collectors like to see works of art in the flesh, but galleries and auction houses are now embracing technologies that help them establish their presence in the virtual world. “Online viewing rooms” facilitated by art fairs use augmented reality for clients to browse works in gallery settings and interact with artists.

Galleries and auction houses are also creating a copious amount of relatable content on social media. The Chinese auction house Guardian’s WeChat account, for example, features an article titled “How many steps does it take for a newbie to become an emerging collector” which gives tips including “focus on the media you like” and “buy an artwork as a reward for yourself.”

A significant number of galleries and auction houses have also partnered with online sales platforms active in China, including Artsy, Yitiao’s online auction platform, and online auction app ArtPro. These digital tools allow users to buy or bid with a few clicks and to access the price database of past sales, which brings some transparency to the market that can appear esoteric to buyers without expert knowledge or prior experience. “Five years ago, there just wasn’t a possibility to do art sales online,” says Qin. “But now, putting works on [online] platforms or into online viewing rooms shows that [galleries] are open to welcoming new collectors to join the game.”

Apart from the size of their wallet and the amount of collecting experience, high net worth and middle-class individuals might take different approaches to their purchases. According to a number of sources in the art industry, the former, often professional collectors, might be more concerned about the growth potential of artworks’ market value, while middle-class, amateur buyers tend to prefer works that they identify with.

“Some professional collectors put their purchases directly into tax-free storage facilities and might not even look at them before the works change hands to another owner,” observes Qin, “whereas [middle-class buyers] might take a more personal interest in the artworks, because they often purchase them to decorate [their living space].”

TWOC spoke to a Shenzhen resident in her mid-20s who is pursuing a career in consulting about her decision to collect her first artwork after visiting an art fair. “At the time, my family was renovating our apartment, so I thought about buying a painting that would match it,” she shares with TWOC, preferring to remain anonymous.

After learning about artists through galleries and consulting friends who work as art advisors, she decided on a work by Chinese artist Wang Tiande, who is known for his innovations on Chinese ink painting and calligraphy. “He uses incenses to burn [paper surfaces] in order to create,” she explains, “The process of destruction is given a new life. I like that idea.”

Others have taken an alternative approach to harvest an artwork’s aesthetic value. China has long had a robust market in making copies of artwork, with “painting workers” in Dafen village in Shenzhen well-known for supplying homes, hotel chains, and other businesses around the world with replicas of famous oil paintings. These days, hundreds of venders on Taobao, where copyright is not the priority, are ready to render onto canvas any work desired by clients, with prices calculated based on the image’s complexity and the canvas size.

A Shanghai-based designer educated at China Academy of Art, who does not want to be identified, saw a large 1-meter-by-2-meter painting at an art fair that impressed her with its opaque green and blue colors. But the painting, priced around 150,000 RMB (about 25,000 US dollars), was well beyond her budget. “So I took a photo of it and sent it to a painting supplier that I work with and ordered a copy [for a few hundred yuan],” she says.

The painting now hangs in the living room of the designer’s Shanghai apartment, and she seems surprised when TWOC asks her whether she sees a difference between her copy and the original. “What do you think? The difference is of course the money.”

– Ningyi Xi(席寧忆)

Young visitors browsing the exhibits during the 2019 Art Fair in Hotel (AFIH) in the suites of the Peninsula Beijing

AFIH features small, reasonablypriced oil paintings and sculptures suitable as home decoration

A contemporary art exhibition marketed as “trend art” in Lizhu Art Space in Changsha, Hunan province

Colorful, trendy statues attract young customers in an art shop in Shanghai

The NGART Festival, also specializing in trend art, at Beijing Quanyechang Culture and Art Center in 2021