Step-up approach in emphysematous hepatitis: A case report

2022-04-02SilkeFrancoisMaridiAertsHendrikReynaertRuthVanLanckerJohanVanLaethemRastislavKundaNouredinMessaoudi

Silke Francois, Maridi Aerts, Hendrik Reynaert, Ruth Van Lancker, Johan Van Laethem, Rastislav Kunda,Nouredin Messaoudi

Silke Francois, Department of Gastroenterology, Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Brussels 1090, Belgium

Maridi Aerts, Hendrik Reynaert, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Brussels 1090, Belgium

Ruth Van Lancker, Department of Intensive Care, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Brussels 1090, Belgium

Johan Van Laethem, Department of Infectious Diseaeses, Vrije Universiteit Brussel,Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Brussels 1090, Belgium

Rastislav Kunda, Nouredin Messaoudi, Department of Surgery, Vrije Universiteit Brussel,Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Brussels 1090, Belgium

Nouredin Messaoudi, Department of Surgery, Europe Hospitals, Brussels 1180, Belgium

Abstract BACKGROUND Emphysematous hepatitis (EH) is a rare, rapidly progressive fulminant gasforming infection of the liver parenchyma. It is often fatal and mostly affects diabetes patients.CASE SUMMARY We report a case of EH successfully managed by a step-up approach consisting of aggressive hemodynamic support, intravenous antibiotics, and percutaneous drainage, ultimately followed by laparoscopic deroofing. Of 11 documented cases worldwide, only 1 of the patients survived, treated by urgent laparotomy and surgical debridement.CONCLUSION EH is a life-threatening infection. Its high mortality rate makes timely diagnosis essential, in order to navigate treatment accordingly.

Key Words: Emphysematous hepatitis; Septic shock; Step-up approach; Percutaneous drainage; Laparoscopic deroofing; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Emphysematous hepatitis (EH) is a rare life-threatening condition that results from a necrotizing gasforming infection of the liver parenchyma. The pathogenesis is poorly understood, although rare published case series have shown that diabetes mellitus was present in most patients[1-6]. Diagnosis of EH is based on radiological findings on computed tomography demonstrating hepatic intraparenchymal gas without the typical fluid-air level seen in pyogenic abscesses. Early recognition is crucial in attempts to decrease mortality, although there is still discussion regarding the appropriate management,as almost all documented cases evolved unfavorably[1-4,6-11]. This report presents the successful management of a critically ill patient with EH using a step-up approach.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 70-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with acute epigastric pain of 1 h duration.

History of past illness

The patient had a history of well-controlled diabetes mellitus, cholecystectomy, and heterozygote alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

Physical examination

Clinical examination revealed the patient to be in no distress, fully alert and oriented, and presenting with epigastric tenderness without signs of peritonitis. She had no fever, a pulse rate of 82 beats/min,blood pressure of 128/68 mmHg, and normal respiratory rate and oxygen saturation.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory investigation performed within a few hours after onset of pain showed a total bilirubin of 0.28 mg/dL, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase of 45 U/L, glutamic pyruvic transaminase of 30 U/L, γglutamyltransferase of 91 U/L, alkaline phosphatase of 99 U/L and lipase of 3518 U/L. Complete blood count, C-reactive protein, coagulation, and renal function were within normal limits. Cardiac evaluation by electrocardiogram and cardiac enzymes confirmed normal findings. As acute pancreatitis was suspected, the patient was initially managed conservatively,viaintravenous fluid resuscitation and pain relief. However, within hours after admission, the patient deteriorated rapidly, developing signs of severe septic shock. She was transferred to the intensive care unit, requiring mechanical ventilation and aggressive hemodynamic support.

Imaging examinations

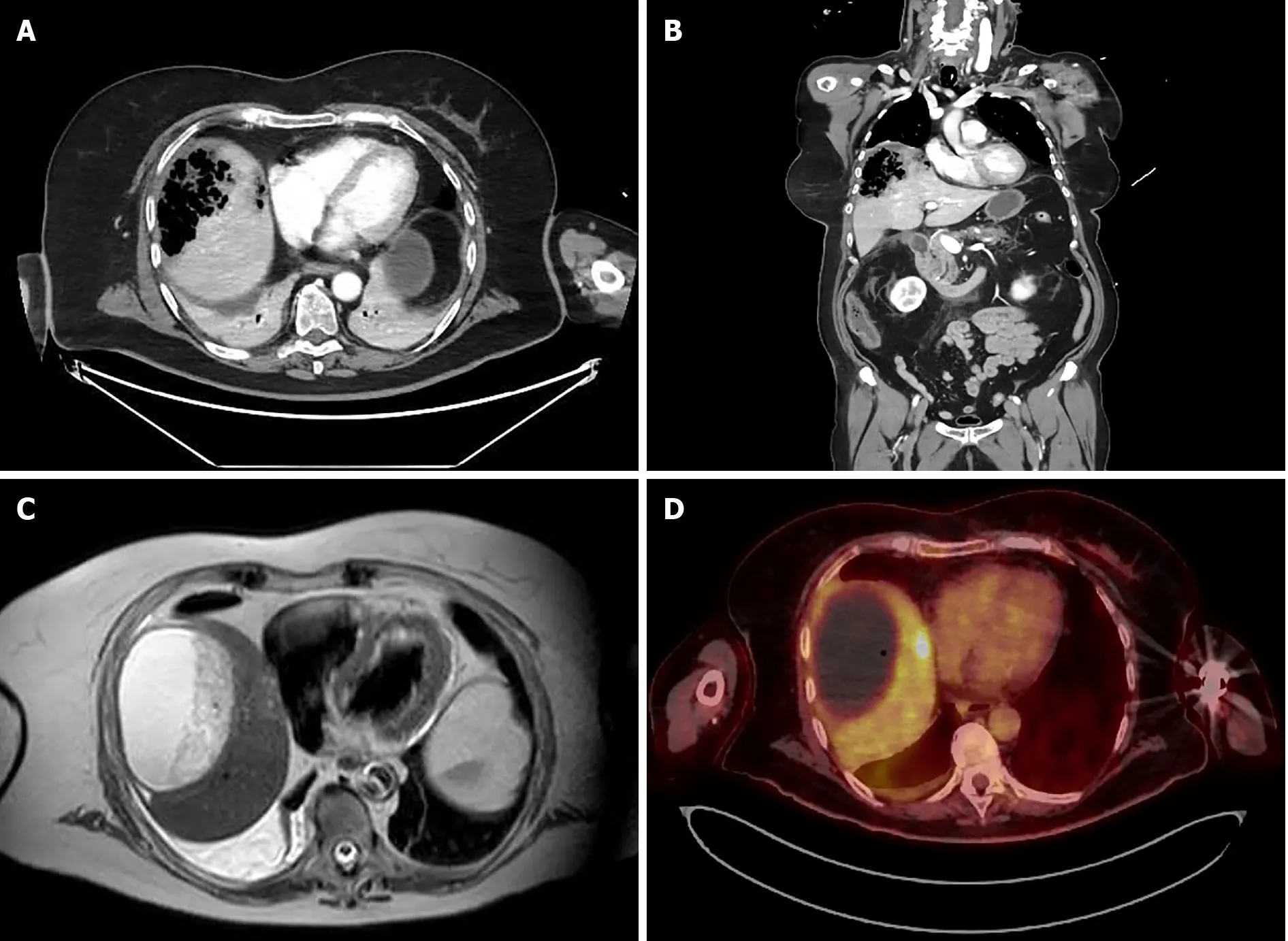

After initial resuscitation, a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, showing a large (9 cm)air-filled cavity in the right liver lobe (Figure 1A and B). The bile duct was only mildly dilated in this cholecystectomized patient but nonradiopaque choledocholithiasis could not be ruled out. No apparent inflammation surrounding the pancreas was visible on scans.

Figure 1 Imaging of emphysematous hepatitis. A and B: Axial (A) and coronal (B) computed tomography scans on admission, showing a 9 cm air-filled cavity in the right liver lobe; C: Magnetic resonance imaging, showing a 10 cm fluid-filled collection in the right liver lobe with heterogeneous content at 6 wk after initial presentation; D: Positron emission tomography performed at 9 wk after initial presentation, showing no metabolic activity in the large collection in the right liver lobe and a 2-cm nodule with positive metabolic activity in segment VIII.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY EXPERT CONSULTATION

As soon as the patient clinically deteriorated, multidisciplinary consultations between gastroenterology,hepatobiliary surgery, intensive care, interventional radiology and microbiology were performed repeatedly.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on the CT-graphic findings, a diagnosis of EH was made.

TREATMENT

The patient was treated with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (meropenem, vancomycin, and amikacin). Subsequent CT-guided percutaneous pigtail catheter drainage yielded no significant amount of fluid or pus. The pigtail drain was then flushed by continuous irrigation of 1 L saline solution per 24 h. Because of elevated serum lipase suggesting pancreatitis and a mildly dilated bile duct, albeit without biochemical cholestasis, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed in this rapidly deteriorating patient. A cholangiogram showed normal biliary anatomy, and clear bile was visible after endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla Vateri.

Antibiotics were rationalized to ceftriaxone and metronidazole after blood and fluid cultures revealedEscherichia coli,Streptococcus anginosus, andKlebsiella oxytocaas microbial pathogens. Continuous pigtail irrigation was stopped after 3 d, and the drain was removed after 5 d because of no output. The patient was weaned from the ventilator after a week and transferred to the ward after 2 wk in intensive care.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient continued to recover favorably and was discharged 1 mo after admission, with intravenous antibiotics at home. During her stay, a colonoscopy and transthoracic echocardiogram were performed to rule out other potential etiologies. At the time of discharge, a CT scan showed a 90 mm × 47 mm liquefied collection in segment VII. Follow-up included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET). MRI, performed 6 wk after initial admission, showed a 10-cm cystic formation in liver segments VII and VIII that contained both fluid and necrotic debris (Figure 1C) that were not metabolically active on the PET scan. However, in segment VIII, a 2-cm PET-positive nodule was detected (Figure 1D). Surgical drainage was performed because of the heterogenous content of the large intrahepatic collection in segments VII-VIII and the undetermined nature of the 2-cm lesion in segment VIII. Three mo after onset, the patient underwent laparoscopic deroofing and debridement of the hepatic collection in segment VII and partial hepatectomy of the 2-cm lesion in segment VIII(Figure 2). No malignancy was found in the resected specimens, and microbiological cultures were sterile. Hence, antibiotics were discontinued after a total treatment of 14 wk. The patient had an uneventful recovery but was hospitalized again after a few weeks for coronavirus disease 2019 infection.To date, the patient is asymptomatic and without recurrence on follow-up imaging.

Figure 2 Laparoscopic treatment of emphysematous hepatitis. A: Semi-pone positioning of the patient; B: Laparoscopic view of liver segments VII and VIII after mobilization of the right liver lobe; C: Laparoscopic deroofing of the liver capsule of segments VII and VIII; D: Partial hepatectomy of segment VIII and placement of a surgical drain in the remaining cavity.

DISCUSSION

EH is a severe, life-threatening infection of the liver parenchyma by gas-forming bacteria. To the best of our knowledge, 11 cases of EH have been previously reported in the literature (Table 1)[1-11].Remarkably, only 1 of those patients, treated by urgent laparotomy and surgical debridement, was reported to have survived this dismal clinical entity[5]. However, a mixed collection of necrotic debris and air was diagnosed by CT and intraoperatively, making the probability of a pyogenic liver abscess or at least coexistence of both entities more likely. The other patients all died within 3 d of severe multiple organ failure in the setting of fulminant septic shock. This case report describes the favorable outcome of a patient diagnosed with EH and managed by a step-up approach consisting of initial aggressive resuscitation, systemic antimicrobial therapy, and percutaneous radiologically guided drainage followed by laparoscopic surgical debridement.

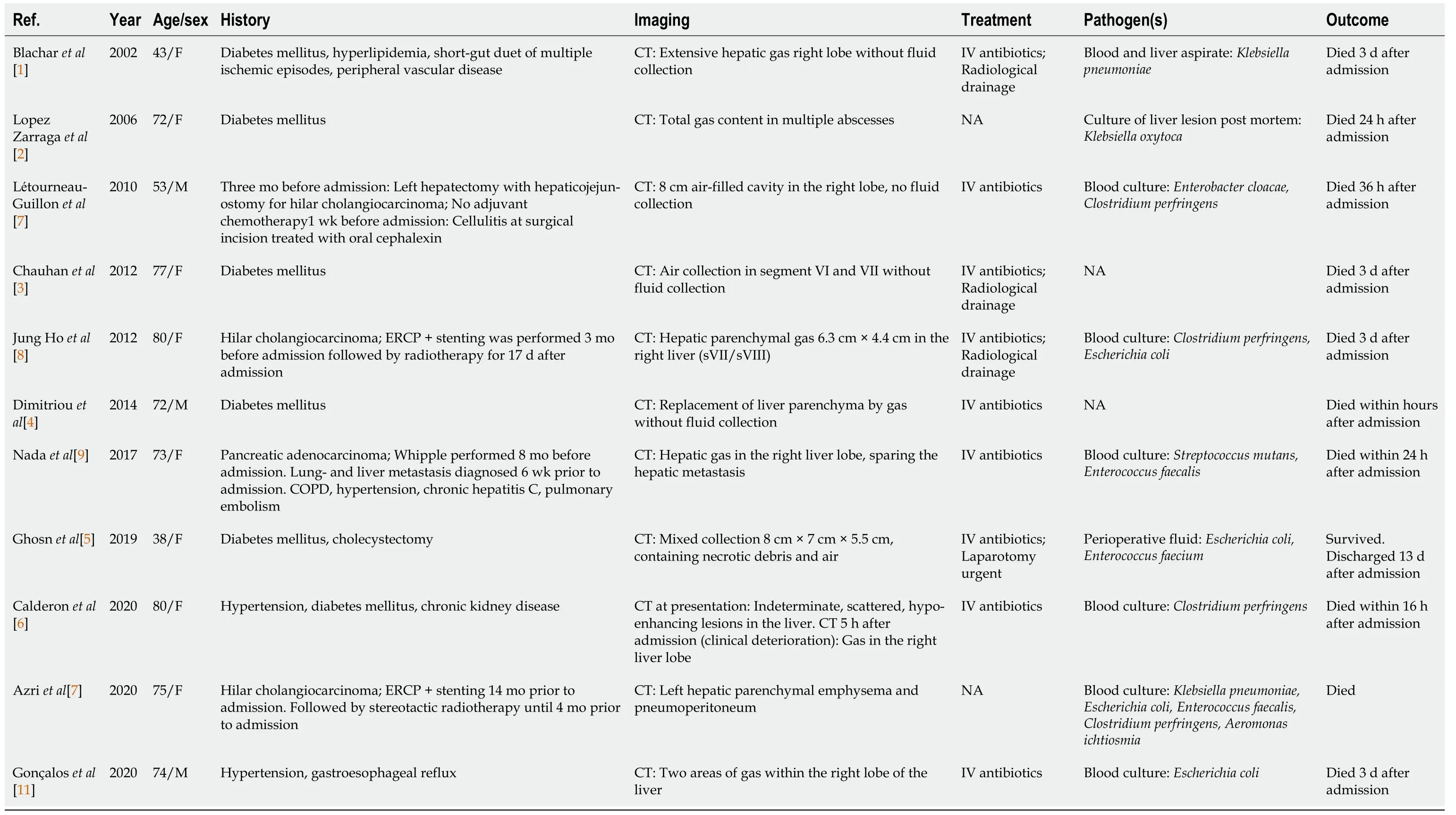

Table 1 Emphysematous hepatitis case reports in the literature

EH occurs predominantly in women, and diabetes mellitus seems to be a predisposing condition.Abdominal pain and fever are the most common clinical manifestations of the disease. Diagnosis of EH is confirmed by the presence of parenchymal gas in the liver on CT in the absence of intrahepatic fluid collection. CT is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing EH, as it permits early detection,evaluation of the extent and location of liver involvement, and excludes other etiologies of acute abdominal pain causing septic shock. Importantly, parenchymal gas in the liver has to be differentiated from air in other liver structures. Air can be observed within bile ducts (e.g., following endoscopic sphincterotomy), portal veins (e.g., as a result of bowel infarction), in infarcted liver (e.g., after liver transplantation), and in pyogenic liver abscesses. In contrast to EH, characteristics of pyogenic liver abscesses on CT scans include peripheral enhancing and centrally hypoattenuating (dense or) liquefied collections containing gas bubbles or air-fluid boundaries[12].

Emphysematous infections in the abdomen are known to occur in the gallbladder, stomach, pancreas,and urinary tract[13]. Clinically, pathologically, and radiologically, EH shares features with emphysematous pyelonephritis. The latter is defined as an acute necrotizing, gas-forming infection in the kidney associated with a poor prognosis. Bacterial pathogens cultured in emphysematous pyelonephritis includeEscherichia coliand members of the generaKlebsiella,Enterobacter,Pseudomonas,ProteusandStreptococcus[1,14]. As shown in Table 1, the same causative pathogens can be found in EH.

The pathophysiology of emphysematous infections is believed to be caused by mixed acid bacterial fermentation from tissue necrosis resulting in the production of hydrogen (15%), nitrogen (60%), oxygen(5%), and carbon dioxide (5%). Diabetes is known to predispose to emphysematous infections by providing high levels of glucose used as a substrate by the microorganisms[3,15]. Last, diabetes as well as other risk factors for microangiopathy, may contribute to slow transport of catabolic products,leading to accumulation of gas[3,15]. Similar to most previously published cases of EH, our patient was diabetic. Noteworthy was the well-controlled disease state, with glycated hemoglobin of 5.8%,suggesting that factors other than circulating glucose levels may have been of importance.

With advances in cross-sectional imaging and localization, percutaneous drainage has now become the treatment of choice of pyogenic abscesses of the liver. By analogy, less invasive means seem to be a first-line approach in EH as well. Although often ineffective in previously reported cases, our patient responded to early aggressive medical management and radiologically guided drainage. Surgical intervention in this case was not intended as a salvage therapy but rather as a step-up to initial conservative management. Laparoscopic deroofing and debridement of necrosis was undertaken 3 mo after the initial presentation. Given the dorsal localization of the hepatic area involved in our patient, a semiprone position was chosen to allow laparoscopic visualization of posterior segments and partial hepatectomy of segment VII and VIII, avoiding laparotomyviaa right subcostal incision.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, EH is a serious potentially life-threatening infection of the liver. We report the successful treatment of a patient diagnosed with EH by adopting a multimodal step-up approach including rigorous fluid resuscitation, early hemodynamic support, broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy and percutaneous radiologically guided drainage followed by minimally invasive surgical treatment.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Francois S designed the report and collected the patient’s clinical data; Francois S and Messaoudi N wrote the manuscript; Aerts M, Reynaert H, Van Lancker R, Van Laethem J and Kunda R read and approved the final manuscript.

Informed consent statement:Consent was obtained from the patient (on 09/06/2021) for publication of this anonymized case details and accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Belgium

ORCID number:Silke Francois 0000-0003-4303-0296; Maridi Aerts 0000-0002-7595-7988; Hendrik Reynaert 0000-0002-2701-5777; Ruth Van Lancker 0000-0002-8462-9134; Johan Van Laethem 0000-0002-2490-216X; Rastislav Kunda 0000-0001-5632-2402; Nouredin Messaoudi 0000-0003-2799-2604.

S-Editor:Li X

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Li X

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- COVID-19 and liver disease: Are we missing something?

- Glycogen hepatopathy in type-1 diabetes mellitus: A case report

- Learning from a rare phenomenon — spontaneous clearance of chronic hepatitis C virus post-liver transplant: A case report

- Timing of surgical repair of bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A systematic review

- β-arrestin-2 predicts the clinical response to β-blockers in cirrhotic portal hypertension patients: A prospective study

- Modified EASL-CLIF criteria that is easier to use and perform better to prognosticate acute-on-chronic liver failure