Native/Non-native English Speakers’Attitudes:Addressing Learners’Goals and Needs Towards Pronunciation Issues

2022-03-03AnnaMariaDeBartolo

Anna Maria De Bartolo

The study attempts to explore native and non-native English speakers’ attitudes towards accents and pronunciation-related issues. The sample group surveyed is composed of non-native English speakers, specifically, Italian students studying at the University of Calabria (Italy) and native English speakers from Alberta University (Canada) and Florida Atlantic University (USA). An online link to a questionnaire was sent via email to all participants and was used as a research instrument to collect quantitative data. The research questions will investigate learners’ attitudes in relation to the following aspects: accent and identity, beliefs about native/non-native accents, impact of pronunciation on communication, and learners’ expectations towards pronunciation teaching. Firstly, mean scores in relation to the aforementioned aspects will be examined. Secondly, differences between native/non-native speakers’ responses will be statistically analysed. Thirdly, non-native learners’ responses will be correlated with their proficiency level in English to identify the extent to which language competence may affect learners’ attitudes. The study aims to gain useful insights that may hopefully raise students and teachers’ awareness of what models we expect learners to imitate and attain in the English language classroom, how appropriate and relevant these may be especially in the globalized English world where non-native speakers will increasingly use English in a diversity of forms to achieve their communicative goals. The preliminary results will be presented and pedagogical considerations suggested.

Keywords: accents and pronunciation, ELF, intercultural communication, native/non-native English speakers, attitudes

Introduction

The impact and significance of pronunciation teaching is a major aspect in second language teaching and research. Research issues have addressed pronunciation as related to one’s identity and its implications in terms of socio-cultural considerations, the dichotomy between native and non-native accents of English, roles and models in pronunciation teaching, what pronunciation norms and features (if any) impact on successful intercultural communication. Various studies report how language teachers consider pronunciation teaching as an essential component in second language teaching, although they manifest dissatisfaction and concern over the amount and quality of pronunciation training provided (Henderson, 2013; Henderson et al., 2012;Waniek-Klimczak, 2013; Buss, 2015). On the other hand, pronunciation teaching has not been given a great deal of attention on the part of EFL material writers, curriculum designers and language instructors.

The present paper will draw attention to pronunciation issues by exploring learners’ views. Specifically, the study will examine beliefs, goals and needs of university students belonging to two different groups. The first group will be composed of non-native English speakers, Italian university students studying at the University of Calabria (Italy). The second group will include mainly native speakers of English, from University of Alberta(Canada) and from Florida Atlantic University (USA). An online link to a questionnaire was sent via email to all participants and was used as a research instrument to collect quantitative data. The study will be divided in three parts. The first part will analyse learners’ attitudes on the basis of 4 macro-categories as specified in the research objectives. Secondly, comparisons between native and non-native speakers’ responses from the overall sample will be carried out by means of statistical analysis. Finally, a correlation between non-native speakers’ responses and their English language competence will be explored. Exploring learners’ attitudes may provide interesting hints that may further our knowledge of the extent to which pronunciation affects successful communication among native and non-native speakers of English, identify possible gaps in the approach to pronunciation teaching and possibly revise current beliefs and practices. Ultimately, the study hopes to raise teachers and students’ awareness of which goals and needs pronunciation teaching should address in the dynamic, evolving, multifaceted English world as well as the direction pronunciation teaching may be taking in increasingly changing social, cultural and academic domains.

Theoretical Background

Literature Review

The field of pronunciation teaching has been receiving in the last decades a renewed interest (Derwing & Munro, 2005) which has contributed to address pronunciation issues from different perspectives. For instance, areas of investigation have centred around teachers lack of confidence to teach pronunciation (Baker, 2011; Foote, Holtby, & Derwing, 2011; Fraser, 2000; Macdonald, 2002), pronunciation training and professional development for teachers (Burns, 2006; Foote, Trofimovich, Collins, & Soler Urz-ua, 2016; Henderson et al., 2012; Murphy, 2014), the importance and role of pronunciation for successful communication (Derwing, Munro, & Wiebe, 1998; Hahn, 2004), how L2 listeners perceive non-native accented speech (Lippi-Green, 1997; Munro, 2003). The emergence of English as a lingua franca (ELF), and the role English has acquired as the main language for intercultural communication globally (Baker, 2015), has favoured the rise of a number of studies which have examined non-native speakers’ interaction in ELF settings also in relation to pronunciation. Findings (Deterding, 2005; Jenkins, 2000, 2009, 2012; Matsuda, 2012; McKay, 2012) have highlighted that the use of native English pronunciation norms is unrealistic and unproductive, especially in those contexts where the majority of interactions occur between non-native speakers of English.

Especially in Expanding circle countries (Kachru, 1992), empirical data have revealed that communicative success is achieved through intelligible pronunciation rather than through adherence to native speaking pronunciation features which, on the contrary, may hinder intelligibility and communication (Jenkins, 2000, 2002). Scholars, have given various definitions of intelligibility. “By intelligibility we refer to the need to create discourse that is understood by participants within a given communicative framework” (Sifakis & Souguri, 2005,p. 469). Munro et al (2006) define “intelligibility” as “the extent to which a speaker’s utterance is actually understood” (Kawanami, 2009, p. 5) and in this sense it is different from “comprehensibility” which concerns “a listener’s estimation of difficulty in understanding an utterance” (2009, p. 5). Smith (1987) studied intelligibility and comprehensibility and concluded that native speakers are not easily understood by non-native speakers nor are they good at understanding other accents of English (in Kawanami, 2009, p. 5). Jenkins (2000, 2003) has extensively focused on pronunciation features that may facilitate intelligibility and successful communication between non-native speakers in ELF contexts as well as on the interactional processes which favour intelligibility, such as negotiation strategies and adjustment moves (confirmation checks, clarification requests, code-mixing, paraphrasing, repetitions) which are considered to prevent communication breakdowns. However, a number of studies in Outer circle countries (Bamgbose, 1998) and in Expanding circle countries (Dalton et. al., 1997; Grau, 2008; Smit & Dalton, 2000; Timmis, 2002) have shown how teachers and learners prefer to aim for an approximation of a native-like pronunciation rather than a local or internationally acceptable one, even when they simultaneously believe that a non-native accent is acceptable and that priority should be given to intelligibility. Therefore, most empirical data overall tend to conclude that EFL teachers prefer native pronunciation models for teaching (Henderson et al., 2012; Campos, 2011; He & Li, 2009; Sifakis & Sougari, 2005) which they consider to be the ‘correct’ model, what students need to look at, imitate and ultimately attain (Jenkins, 2005; Timmis, 2002).

Pronunciation and Socio-cultural Identity Theories

Pronunciation definitely plays a major role in communication also because it impacts on the way we perceive and are perceived by others and it intertwines with issues of “sociocultural identity” (Sifakis & Sougari, 2005, p. 470). “Sociocultural identity is a complex construct that defines the relationship between the individual and the wider social and cultural environment” (2005, p. 470). One important way to express “sociocultural identity” is through language and pronunciation. It is through pronunciation that “we project our regional, social and ethnic identities…. which are deeply-rooted, often from a very early age, and may prove subconsciously resistant to change even if on the surface, as language learners, we profess the desire to acquire a nativelike accent in our L2” (Setter & Jenkins, 2005, p. 1). Acquiring an L2 accent may be considered by learners either consciously or unconsciously as the expression of a new ego which takes the individual away from his L1 identity, his/her roots and therefore may be resisted. In this respect, Bamgbose (1998) talks about “love-hate relationship”which means being torn between not wanting to sound like a native speaker while finding the accent desirable and fascinating at the same time.

Socio-psychological research as well as sociolinguistic research challenged (in Setter & Jenkins, 2005) the old concept of “accent reduction” which tended to eliminate L1 traces from L2 pronunciation. Levis (2005) defined it the “nativeness principle” which “holds that it is both possible and desirable to achieve nativelike pronunciation in a foreign language” (in Thir, 2016, p. 2). On the contrary, it is argued (in Setter & Jenkins 2005) that the “accent reduction” principle is best replaced by the “accent addition” one which enriches and expands learners’ repertoire with L2 pronunciation features.

According to Jenkins (2000, 2002), the addition of L2 features to the learners’ repertoires includes the following stages: (1) addition of ELF core (necessary for mutual intelligibility) items receptively and productively; (2) addition of a range of NNS English accents to the learner’s receptive repertoire; (3) addition of accommodation skills; (4) addition of non-core (not necessary for mutual intelligibility) items to the learner’s receptive repertoire; (5) addition of a range of NS English accents to the learner’s receptive repertoire (Setter & Jenkins, 2005, p. 6; Jenkins, 2002). Those learners who want to maintain their L1 identity but at the same time want to understand and be understood will possibly set their pronunciation goals according to the first 3 stages, on the contrary, those learners who want to be able to understand NS pronunciation are likely to aim for all five stages. In any cases, losing traces of L1 accent and therefore L1 identity is not desirable or necessary to achieve communicative goals during interaction. As studies have largely drawn attention to, a person can have a strong accent without losing intelligibility (Derwing & Munro, 2005; Munro & Derwing, 1995; Flege, Takagi, & Mann, 1995; Munro, Flege, & MacKay, 1996). In this view, intelligibility, rather than approximation to native-like pronunciation, should be the goal of pronunciation teaching (in Thir, 2016, p. 6).

It is necessary to point out the role attitudes towards native/non-native accents of English play in communication and the extent to which attitudes can impact on intelligibility (Zoghbor, 2014). Studies show evidence of negative attitudes towards certain accents of English which are proved to affect speakers’intelligibility (Jenkins, 2007; Smith & Nelson, 2006; Rajadurai, 2007; Scales et al., 2006; Pickering, 2008). They reveal that “negative attitudes will tend to increase intelligibility/comprehensibility thresholds” (Zoghbor, 2014, p. 168).

In light of these findings, it is certainly useful to continue investigating the factors underlying attitudes towards native/non-native accents of English, in the attempt to gain a more comprehensive knowledge of the way communication unfolds in ELF communicative environments, promote higher tolerance towards non-native accents, and raise both learners and teachers’ awareness of fundamental issues that so far have not been given a large space in the language classroom but definitely need to be pursued (Zoghbor, 2014).

The Study

Research Objectives

The article reports the findings of a survey aimed at investigating learners’ beliefs and attitudes towards a number of pronunciation-related issues. More specifically, learners were surveyed in relation to four specific aspects: the relation between accent and identity, their beliefs about the significance of native and non-native accents, the role accents may play in intercultural communication, and their expectations and beliefs towards pronunciation teaching. Secondly, differences between native and non-native speakers’ responses from the sample group were analysed in relation to the aforementioned aspects and statistically significant differences observed. Finally, non-native learners’ responses were statistically correlated to their proficiency level in English to identify the extent to which their attitudes are affected by their language competence. The study aims to raise students and teachers’ awareness of what models we expect learners to look at in the language classroom, how appropriate and relevant these may be in the globalized English world where non-native speakers will increasingly use English in a diversity of forms to achieve their communicative goals.

Participants and Settings

The questionnaire was administered online through a link the author has forwarded to colleagues in three different academic contexts, the University of Calabria (Italy), where the majority of respondents are native Italian speakers, and where Italian is the main medium of academic instruction, the University of Alberta (Canada) and Florida Atlantic University (USA), where the author expected to gather data specifically from native English speakers. 175 respondents had completed the questionnaire when it was decided to analyse the data. Among them, 155 were female and 20 were male. As far as Study sector is concerned, the majority belongs to the humanities field, as table 1 shows. In terms of language background, 154 respondents reported to be non-native English speakers and 21 native English speakers. Further, non-native speakers were asked to specify their language competence, and as table 2 shows, most of the students surveyed rated their proficiency level between pre-intermediate and intermediate.

Methodology

MacKey and Gass (2005, p. 92) claim that “a survey in the form of the questionnaire is one of the most used methods in order to collect data consisting of a variety of questions in second language research”. In order to elicit students’ beliefs and attitudes, this research study has drawn on a questionnaire which has been organized in different sections. The first part presents a preliminary section aimed at collecting participants’ demographic information, such as gender, study sector and linguistic background. They were required to indicate whether they are native or non-native speakers of English. Non-native speakers were asked to rate their level of competence in English on a scale from elementary to advanced. A five-point Likert scale ranging from 1= strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree was employed to allow students to express their level of agreement with the statements provided. The statements were written both in Italian and English to make sure lower-level students did not have any linguistic uncertainties or doubts in reporting their answers. The objectives and motivations of the survey were clearly stated at the beginning of the first section which also pointed out that the survey has been designed for academic and study purposes exclusively and strictly respected participants’ anonymity.

The second part of the questionnaire was grouped in four sections which specifically address the research points mentioned in the research objectives: the relation between accents and speakers’ identity, beliefs towards native and non-native accents, the perceived impact of accents on successful communication, participants’ beliefs towards pronunciation teaching. The questionnaire has been adapted from two different studies, in particular, most of the sections are based on Tamimi Sàd (2018)’s investigation of Iranian EFL learners’ views towards accent and identity, while a number of statements have also been adapted from Buss’s study (2015) on Brazilian EFL teachers’ beliefs regarding pronunciation.

Accent and Identity

1. A person’s accent can indicate his/her socio-economic status.

2. A person’s accent can indicate his/her job.

3. A person’s accent can indicate his/her education.

4. One can show his/her identity through his/her accent.

5. A person’s accent does not have anything to do with his/her identity.

6. I like to show my identity through my accented speech.

Beliefs about Native and Non-native Accents

7. It is fine that non-native speakers of English have foreign accents.

8. It bothers me when someone speaks English with a foreign accent.

9. Native speakers of English are the best model of English accent.

10. I think it is generally important for non-native speakers to speak with a native English accent.

11. A heavy accent can be a cause of discrimination against non-native speakers.

12. I think that trying to learn a native English accent is a waste of time and energy.

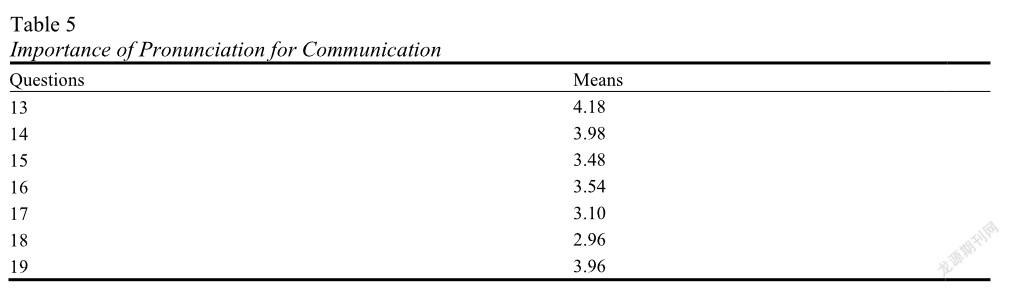

Importance of Pronunciation for Communication

13. Pronunciation is important for communication.

14. I often hear English spoken by non-native speakers of English.

15. I can guess where a speaker is from based on their pronunciation.

16. I don’t care about someone’s pronunciation as long as I can understand it.

17. It bothers me when someone’s pronunciation is difficult to understand.

18. A non-native accent can facilitate communication between non-native speakers of English.

19. People who have good pronunciation can better communicate with both native and non-native speakers.

Pronunciation Teaching

20. I expect teachers of English to have native-like pronunciation.

21. The goal of pronunciation teaching should be to eliminate, as much as possible, foreign accents.

22. An English teacher with a non-native accent is more intelligible than a teacher with a native accent.

23. I think teachers of English should present the accents of both native and non-native speakers in lessons.

24. It is acceptable to be taught ‘international’ pronunciation of English (international means that it is not identified by any specific variety, i.e. British/American, etc.).

25. Pronunciation teaching should help make students comfortably intelligible to their listeners.

Data Analysis and Discussion—Part 1

The data analysis section has been carried out using SPSS version 27. Tables 3 to 6 below show the mean scores calculated on the overall sample, 175 respondents. Means were reported for each question according to the four sections in the questionnaire.

From a first analysis of mean scores, as far as the section Accent and Identity is concerned (table 3), it emerges that respondents do not seem to associate foreign accents to either job conditions, education or socio-economic status. Therefore, these first results do not support what findings have revealed in terms of negative perceptions and stereotypes towards non-native speakers on the basis of accent. (Kang & Rubin, 2009; Dovidio et al, 2010; Hanzlíková & Skarnitzl, 2017). Moreover, respondents do not seem to consider accented speech as a sign of a unique, distinctive identity, as question 6, I like to show my identity through my accented speech, reveals (mean score 2,46). We may suggest that, in their view, there is no connection between a speaker’s accent and the expression of his/her identity.

The next section (see table 4) which surveys attitudes towards native and non-native accents, raises interesting issues. Question 7, It is fine that non-native speakers of English have foreign accents, (mean score 3,74) suggests that the participants in the study are likely to acknowledge and accept that non-native speakers speak English with non-native accents and they are fine with it. Similarly, question 8, It bothers me when someone speaks English with a foreign accent, and question 11, A heavy accent can be a cause of discrimination against non-native speakers, present low mean scores (1,85; 2,69). These first results indicate that respondents disagree with the above statements, they do not seem to manifest any negative perceptions towards foreign accents nor they feel foreign accents may cause discrimination against non-native speakers, as a number of empirical studies have on the contrary emphasized (Dovidio et al, 2010; Lindemann, 2005; Timming, 2017).

Nonetheless, when surveyed about the best model of accent to acquire, the native speaker model seems to be predominant. Question 9, Native speakers of English are the best model of English accent, shows respondents agree with it (mean score 3,72). Question 12, I think that trying to learn a native English accent is a waste of time and energy presents the lowest score in terms of agreement (1,81). What emerges from the analysis of this section is that respondents’ attitudes do not appear to be clear-cut. They do seem to acknowledge the existence of non-native accents of English which are absolutely fine to manifest, moreover, speaking English with a foreign accent is not perceived in negative terms either. Nonetheless, they simultaneously believe that the best model of pronunciation is native English accent. Similar attitudes have already been highlighted in a number of studies(Dalton et. al., 1997; Grau, 2008; Smit & Dalton, 2000; Timmis, 2002) which have shown how teachers and learners aim for approximation of native English accents though they consider non-native accents as acceptable in terms of facilitating mutual intelligibility.

As far as results from the section Importance of pronunciation for communication (table 5), question 13, Pronunciation is important for communication (4,18), question 14, I often hear English spoken by non-native speakers of English (3,98), and question 19 (3,96), People who have good pronunciation can better communicate with both native and non-native speakers, reveal that for the students surveyed, pronunciation has a crucial role in enhancing communication with both native and non-native English speakers. Moreover, respondents’ exposure to non-native English accents and possibly familiarity with multilingual contexts seem to emerge here. This idea is also confirmed in question 15, I can guess where a speaker is from based on their pronunciation, which manifests a moderate level of agreement, (3,48). The issue of intelligibility is particularly highlighted in question 16, I don’t care about someone’s pronunciation as long as I can understand it, (mean score 3,54), which is likely to suggest that successful communication is achieved when intelligibility is ensured, despite pronunciation imperfections or incorrectness. However, as question 18, A non-native accent can facilitate communication between non-native speakers of English, indicates, non-native accents are not considered essential in facilitating communication among non-native speakers, as the mean score reveals (2,96). Overall, it may be concluded that respondents manifest positive attitudes towards non-native pronunciation, that intelligibility is crucial for communication despite pronunciation imperfections, and that attitudes are not likely to be negatively affected by a non-native pronunciation.

In relation to the last section Pronunciation Teaching (see table 6), participants’ responses reveal positive attitudes towards the teaching of international pronunciation of English and the role of pronunciation teaching which should focus on intelligibility. Question 24, It is acceptable to be taught ‘international’ pronunciation of English (international means that it is not identified by any specific variety, i.e. British/American, etc.) and question 25, Pronunciation teaching should help make students comfortably intelligible to their listeners, present mean scores of 3,68 and 4,18 respectively. This latter result is particularly meaningful as it emphasizes, in the participants’ view, how pronunciation teaching should gear students’ needs and goals towards achieving intelligible pronunciation which becomes an important teaching objective compared to acquiring native pronunciation.

The above results are supported by mean scores in question 21, The goal of pronunciation teaching should be to eliminate, as much as possible, foreign accents (2,85), which reveals participants’ disagreement with this statement. Nonetheless, question 20, I expect teachers of English to have native-like pronunciation (mean score 3,31) suggests, as already observed in the second section (table 4), that native pronunciation is still an important requirement for English teachers, therefore confirming what a number of studies in the field have highlighted(Henderson et al., 2012; Campos, 2011; He & Li, 2009; Sifakis & Sougari, 2005).

Data Analysis and Discussion—Part 2

Values higher than+1,96 indicate that non-native speakers have on average answered significantly more favourably, values lower than–1,96 indicate that native speakers have on average answered significantly more positively and therefore in both cases the null hypothesis can be rejected. In all other cases, we accept the null hypothesis, and we can say that there are no significant differences between means in the two groups. This section will discuss results deriving from the analysis of the two tailed distribution Z test.

We observe that compared to the non-native speakers, the native speakers in the study recognize that accents and identities are linked, accents are seen as a mark of identity which can be shown through someone’s accent, as question 4, One can show his/her identity through his/her accent, suggests. A statistically significant difference is observed here. This idea is confirmed by results in question 5, A person’s accent does not have anything to do with his/her identity, which shows that native speakers disagree more with the statement, though no statistical significance is identified in the latter.

Native-speakers manifest higher level of agreement also in question 12, I think that trying to learn a native English accent is a waste of time and energy, in which a statistically significant difference is revealed. This result may suggest that acquiring a native English accent is not considered necessary for the native speakers surveyed, possibly because they have the opportunity to experience and familiarise with non-native accents in communicative and academic contexts characterised by a large number of non-native English speakers (Jenkins, 2015). This attitude aligns with Jenkins’ view (2002) when she points out that striving to attain native-like pronunciation will be an unfeasible and unrealistic effort in ELF contexts where a large number of non-native speakers use English to communicate. Jenkins (2000, 2005) suggests to focus on intelligibility rather than correctness and replace the notion of absolute correctness with one of appropriateness which better fits different contexts and purposes for using the language.

Native-speakers show higher level of agreement, with statistically significant differences, also in question 18, A non-native accent can facilitate communication between non-native speakers of English. This result confirms that the native speakers in the study, being more exposed to multicultural environments where English is the main means of intercultural communication, may be more familiar with non-native accents, more aware of how intercultural communication unfolds when English is used as a lingua franca for intercultural communication and therefore more likely to recognize that intercultural communication is facilitated when non-native speakers of English communicate. Canadian and American Universities welcome staff from different linguistic backgrounds, they are known to be multicultural academic environments where a large portion of academics, staff and students are non-native English speakers (MacCrocklin et al., 2018, p. 141).

Similar results are observed in question 11, A heavy accent can be a cause of discrimination against non-native speakers, which shows that native speakers agree more with the statement with statistically significant differences observed. The result suggests that native speakers may be more aware of issues of stereotyping and discrimination against non-native speakers, in other words, of the negative attitude towards non-native English accents, as a number of research studies have emphasized (Hanzlíková & Skarnitzl, 2017; Timming, 2017; Lindemann, 2011; Dovidio et al., 2010).

On the contrary, question 9, Native speakers of English are the best model of English accent, indicates that non-native speakers are more in favour with this statement, with a significant difference observed. This result reveals that though non-native speakers recognize that English has diversified in many different varieties with different accents which are valid and legitimate, when surveyed about which accent is best to acquire, their preference falls on the native English accent.

Data Analysis and Discussion—Part 3

Finally, it was decided to analyse non-native speakers’ responses in terms of level of English competence. The four categories (elementary, pre-intermediate, intermediate and advanced) were grouped in two: the first for elementary and pre-intermediate; the second for intermediate and advanced and means were calculated for the 25 variables as shown in table 8 below. Secondly, the two tailed normal distribution Z (α/2=0,025) (Bohrnstedt & Knoke, 1994) was employed to test the differences between means in the two groups (elementary -pre-intermediate), (intermediate-advanced) and identify statistically significant differences (see table 8). Only the most relevant aspects from each of the four sections will be highlighted and discussed.

In particular, results show that as far as Accent and Identity is concerned, higher level students seem to recognize that a non-native English accent is an expression of speakers’ identity, which they are willing to manifest as questions 4 and 6 specifically address.

Results from the section Beliefs about native/non-native accents highlight that again more proficient learners acknowledge and accept that English is spoken with different, non-native accents as pointed out in question 7. Moreover, they seem to believe that non-native speakers are discriminated against because of their non-native accents as in question 11.

Statistically significant differences are also observed in the section Importance of pronunciation for communication, in particular in questions 13, 14, 15, 19. Also in these cases, more proficient learners reveal greater awareness of and familiarity with different non-native accents, and they seem quite confident in being able to identify where a speaker is from on the basis of pronunciation. Moreover, their responses indicate that they consider pronunciation as an important aspect to successfully communicate with both native and non-native English speakers.

Finally, in relation to Pronunciation teaching, the high-level students surveyed are the ones who show more positive attitudes with significant differences observed, specifically in questions 20 and 25. This group of respondents seem to believe that pronunciation teaching should focus on achieving intelligibility and successful understanding in communication. Nonetheless, the belief that English teachers are expected to have native accents is still predominant, also for high-level students, as already highlighted in other sections of the analysis.

Conclusion

The study, though tentative and with all the limitations of having relied on statistical analysis exclusively, highlights that, in particular for the native speakers and the most proficient non-native speakers surveyed, intelligibility is prioritized over correctness and it is considered an important goal in pronunciation teaching.These groups of participants manifest more positive attitudes towards non-native accents which they are likely to be more familiar with compared to the non-native speakers and lower-level students in the study. Native speakers recognize that communication is successfully achieved when non-native speakers interact in intercultural communication. On the contrary, when surveyed specifically about which accent is best to attain, the non-native speakers in the study are the ones who manifest stronger preferences for the native English accent. What the present study ultimately aims to suggest is the need to revise learners’ goals and needs, in other words, a shift towards a “transformative approach” (Sifakis, 2014), that will entail raising students’ and teachers’ awareness of the need to pursue more realistic goals when learning English, shift the learning focus towards the real purposes for using the language, and acknowledge that English is a powerful means of communication globally, which allows diverse people from various cultural backgrounds to transcend boundaries, get closer, and enrich their cultural and linguistic baggage. This is certainly a demanding and challenging process which requires teachers firstly, and students secondly, to modify their perceptions about English, a language which is not based on a fixed system of established rules, “shaped and owned by its native speakers” (Sifakis, 2014, p. 135), rather a fluid form of communication strictly dependent on social interaction, which “takes different shapes and forms depending on the interlocutors” (2014, p. 135). If these concepts are transferred to the students, they may become “owners of that knowledge,… capable of molding, transforming and reusing it in authentic communicative settings”(Larsen-Freeman, 2012 in Sifakis, 2014, p. 136). Focusing on teaching native speaker pronunciation, especially in Expanding circle countries (Kachru, 1992), may be an unnecessary effort which does not meet the goals and purposes for using the language in those contexts. What teacher preparation programmes should aim for is making teachers “actively aware of the cognitive, social and cultural” (2014, p. 136) patterns that emerge where non-native speakers communicate and those aspects which make communication successful. This requires teachers to “replace a normative mindset” (Seidlhofer, 2008, pp. 33-34) with one which recognizes that “norms are continually shifting and changing” (2008, pp. 33-34). Incorporating pronunciation features which prioritize intelligibility requires teachers willing to integrate existing activities with listening tasks which engage learners with the rich cultural potential of the English language, and with a variety of different listening input where both native and non-native accents are displayed. Embracing such an approach will encourage teachers to come to terms with their own perceptions, revise existing beliefs and practices and expand their own and their students’perspectives about pronunciation and communication in ELF and multilingual contexts. This is definitely a challenging approach which starts with teachers’ self-examination of their beliefs and uncertainties along with feelings of shame and guilt about a “deficient pronunciation”, gradually moves to a critical assessment of well-established assumptions and ends with an exploration of new avenues and options and with the acquisition of knowledge and skills for implementing a new course of actions (Sifakis, 2014).

References

Baker, A. (2011). Discourse prosody and teachers’ stated beliefs and practices. TESOL Journal, 2, 263–292.

Baker, W. (2015). Culture and identity through English as a Lingua Franca: rethinking concepts and goals in intercultural communication. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501502149

Bamgbose, A. (1998). Torn between the norms: innovations in world Englishes. World Englishes, 17(1), 1-14.

Burns, A. (2006). Integrating research and professional development on pronunciation teaching in a national adult ESL program. TESL Reporter, 39, 34–41.

Buss, L. (2013). Pronunciation from the perspective of pre-service EFL teachers: An analysis of internship reports. In J. Levis, & K. LeVelle (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching conference (pp. 255-264). Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

Buss, L. (2015). Beliefs and practices of Brazilian EFL teachers regarding pronunciation. Language Teaching Research, 1-19.

Campos, M. V. (2011). A critical interrogation of the prevailing teaching model(s) of English pronunciation at teacher-training college level: A Chilean evidence-based study. Literatura y Lingüística, 23, 213-236.

Dalton-Puffer, C., Kaltenboeck, G., Smit, U. (1997). Learner attitudes and L2 pronunciation in Austria. World Englishes, 16(1), 115-128.

Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J. (2005). Second language accent and pronunciation teaching: A research-based approach. TESOL Quarterly, 39, 379-397.

Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., Wiebe, G. (1998). Evidence in favor of a broad framework for pronunciation instruction. Language Learning, 48, 393-410.

Deterding, D. (2005). Listening to estuary English in Singapore. TESOL Quarterly, 39, 425-440.

Dovidio, J. F., Gluszek, A., Ditlmann, J. M. S., & Lagunes, P. (2010). Understanding bias toward Latinos: Discrimination, dimensions of difference, and experience of exclusion. Journal of Social Issues, 66(1), 59-78.

Flege, J. E., Takagi, N., & Mann, V. (1995). Japanese adults can learn to produce English /r/ and /l/ accurately. Language and Speech, 38, 25-56.

Foote, J., Holtby, A., & Derwing, T. (2011). Survey of the teaching of pronunciation in adult ESL programs in Canada. TESL Canada Journal, 29, 1-22.

Foote, J., Trofimovich, P., Collins, L., & Soler Urzua, F. (2016). Pronunciation teaching practices in communicative second language classes. Language Learning Journal, 44, 181-196. doi:10.1080/09571736.2013.784345.

Fraser, H. (2000). Teaching pronunciation. http://wwwpersonal.une.edu.au/~hfraser/pronunc.htm.

Grau, M. (2008). English as an international language—What do future Teachers have to say?. In C. Gnutzmann (Ed.), The globalisation of English and the English language classroom. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Hahn, L. (2004). Primary stress and intelligibility: Research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL Quarterly, 38, 201-223.

Hanzlikova, D., & Skarnitzl, R. (2017). Credibility of native and non-native speakers of English revisited: Do non-native listeners feel the same? Research in Language, 15(3), 285-298.

He, D., & Li, D. (2009). Language attitudes and linguistic features in the ‘China English’ debate. World Englishes, 28, 70-89.

Henderson, A. (2013). The English pronunciation teaching in Europe survey: Initial results and useful insights for collaborative work. In E. Waniek-Klimczak, & L. R. Shockey (Eds.), Teaching and researching English accents in native and non-native speakers (pp. 123-136). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Henderson, A., Frost, D., Tergujeff, E., et al. (2012). The English pronunciation teaching in Europe survey: Selected results. Research in Language, 10, 5-27.

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, J. (2002). A sociolinguistically based, empirically researched pronunciation syllabus for English as an international language. Applied Linguistics, 23(1), 83-103.

Jenkins, J. (2003). Intelligibility in lingua franca discourse. In J. Burton & C. Clennell (Eds.) Interaction and language learning, (pp. 83-97). Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Jenkins, J. (2005). Implementing an international approach to English pronunciation: The role of teacher attitudes and identity. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 535–543. doi:10.2307/3588493.

Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a Lingua Franca: Attitude and identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, J. (2009). English as a lingua franca: Interpretations and attitudes. World Englishes, 28(2), 200-207.

Jenkins, J. (2012). English as a Lingua Franca from the classroom to the classroom. ELT Journal, 66(4), 486-494. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs040.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Global Englishes: A resource book for students (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315761596.

Kachru, B. (1992). The other tongue. English across cultures. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Kang, O., & Rubin, D. (2009). Reverse linguistic stereotyping: Measuring the effect of listener expectations on speech evaluation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 28(4), 441-456.

Kawanami, K. (2009). Evaluation of World Englishes among Japanese junior and senior high school students. Second Language Studies (pp. 1-58). Manoa: University of Hawaii.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2012) Complex systems and technemes. In J. Arnold & T. Murphey (Eds.), Meaningful action: Earl Stevick’s influence on language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lindemann, S. (2005). Who speaks Broken English? US undergraduates’ perceptions of Non-native English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 15(2), 187–212 doi:10.1111/ijal.2005.15.issue-2.

Lindemann, S. (2011). Who’s unintelligible? The perceiver’s role. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 18(2), 223-232.

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. New York: Routledge.

Macdonald, S. (2002). Pronunciation: Views and practices of reluctant teachers. Prospect, 17, 3-18.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. New York: Routledge.

Matsuda, A. (2012). Principles and practices of teaching English as an international language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847697042-002 .

McCrocklin, S., Blanquera, K. P., & Loera, D. (2018). Student perceptions of university instructor accent in a linguistically diverse area. In J. Levis (Ed.), Proceedings of the 9th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching conference, Sept 2017, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, 141-150.

McKay, S. L. (2012). Teaching materials for English as an international language. In A. Matsuda (Ed.), Principles and practices of teaching English as an international language (pp. 70-83). Bristol: Multilingual Matters,. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847697042.

Munro, M. J. (2003). A primer on accent discrimination in the Canadian context. TESL Canada Journal, 20, 38-51.

Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning, 45, 73-97.

Munro, M. J., Flege, J. E., MacKay, I. R. A. (1996). The effects of age of second language learning on the production of English vowels. Applied Psycholinguistics, 17, 313–334.

Murphy, J. (2014). Intelligible, comprehensible, non-native models in ESL/EFL pronunciation teaching. System, 42, 258-269. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.12.007.

Pickering, L. (2008). Speaking English the Malaysian Way—Correct or Not?. English Today, 219-233.

Rajadurai, J. (2007). Ideology and intelligibility. World Englishes, 26(1), 87-98.

Scales J., Wennerstrom A., Richard D., & Wu, S. H. (2006). Language learners’ perceptions of accent. TESOL Quarterly, 40(4), 15-738. doi:10.2307/40264305.

Seidlhofer, B. (2008). Standard future or half-baked quackery? Descriptive and pedagogic bearings on the globalisation of English. In C. Gnutzmann & F. Intemann (Eds.), The globalisation of English and the English language classroom (2nd edition) (pp. 159-173). Tuebingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.

Setter, J., & Jenkins, J. (2015). State of the art review article. Language Teaching, 38, 1-17 doi:10.1017/S026144480500251X.

Sifakis, N. C., & Sougari, A. (2005). Pronunciation issues and EIL pedagogy in the periphery: A survey of Greek State school teachers’ beliefs. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 467-488.doi:10.2307/3588490.

Smit, U., & Dalton, C. (2000). Motivation in advanced EFL pronunciation learners. IRAL, 38, 3/4, 229-246.

Smith, L., & Nelson, C. (2006). World Englishes and issues of intelligibility. In B. Kachru, Y. Kachru, & C. Nelson (Eds.), The Handbook of World Englishes (pp. 428-445). Oxford: Blackwell.

Tamimi Sa’d, S. H. (2018). Learners’ views of (non)native speaker status, accent, and identity: an English as an international language perspective. Journal of World Languages, 5(1), 1-22, DOI: 10.1080/21698252.2018.1500150.

Thir, V. (2016). Rethinking pronunciation teaching in teacher education from an ELF Perspective. VIEWS Vienna English working papers, 25, 1-29. http://anglistik.univie.ac.at/views/.

Timming, A. R. (2017). The effect of foreign accent on employability: A study of the aural dimensions of aesthetic labour in customer-facing and non-customer-facing jobs. Work, Employment and Society, 31,(3), 409-428.

Timmis, I. (2002). Native-Speaker norms and international English: A classroom view. ELT Journal, 56(3), 240-249. doi:10.1093/elt/56.3.240.

Waniek-Klimczak, E. (2013). It’s all in teachers’ hands: The English pronunciation teaching in Europe survey from a Polish perspective. In D. Gabry?-Barker, E. Piechurska-Kuciel, & J. Zybert (Eds.), Investigations in teaching and learning languages (pp. 245-259). Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing.

Zoghbor, W. S. (2014). English varieties and Arab learners in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries: Attitude and perception. AWEJ, 5(2), 167-186.

杂志排行

Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- Ethical Problems in MTI Students’Escort Interpreting from the Perspective of Chesterman’s Models on Translation Ethics

- A Corpus-driven Contrastive Study on Reporting Verbs in Research Articles

- A Contrastive Study of Self-Sourced Reporting Sentence Stems in English and Chinese Journal Articles

- Revenge and Sociality

- A Feature Analysis of Oroqen Ethnic Group’s Semiosphere

- The Media Fusion and Digital Communication of Traditional Murals—Taking the Exhibition of the Series of Tomb Murals in Shanxi During the Northern Dynasty as an Example