Species composition, structure, regeneration and management status of Jorgo-Wato Forest in west Wollega, Ethiopia

2022-02-26KebuBalemiZemedeAsfawSebsebeDemissewGemedoDalle

Kebu Balemi · Zemede Asfaw · Sebsebe Demissew · Gemedo Dalle

Abstract Species composition, structure, regeneration, and management status of Jorgo-Wato Forest (JWF) was studied.Number of individuals, diameter at breast height (dbh) and height of woody species (dbh ≥ 2.5 cm) were counted and measured in each plot.Group discussions with local farmers residing around JWF were carried out to understand the management of the JWF.Forest structural attributes were computed using descriptive statistics; correlation was used to assess relationships between the structural variables.A total of 4313 individuals (dbh ≥ 2.5 cm) with a density of 1477 ha-1 were recorded, the number of species and individuals decreasing with increasing dbh classes.Species with the highest Importance Value Index (IVI) were Pouteria adolfifriedericii (37.7), Syzygium guineense subsp.afromontanum (23.6), Dracaena afromontana (20.5), Chionanthus mildbraedii (15.9), and Croton macrostachyus (12.3).Overall distribution of woody plants across size classes exhibited a reverse J-pattern, suggesting a healthy population structure and good regeneration.Nevertheless, some species were not represented in smaller diameter classes, including juvenile phases, which indicate a lack of regeneration.For these species, monitoring and enrichment planting would be necessary, along with curbing illegal cutting and coffee farming in the natural forest.Management interventions in the JWF need to consider livelihood options and to respect the rights of local communities

Keyword Species composition · Structure · Regeneration · Participatory · Forest Management

Introduction

Forests are global biodiversity-rich ecosystems (Myers et al.2000; Mayaux et al.2005) as they vary considerably in species composition and structure (Thomas and Baltzer 2002).Tropical forests in particular, which represent approximately 44% of the world’s forest areas, harbor much of the known plant species (Mayaux et al.2005).The species richness in a given tropical forest area is exceptionally greater than other forests.As in many other tropical areas, the Afromontane areas of eastern Africa, including the Ethiopian highlands, constitute tropical forests that are exceptionally rich in species, including endemic species (Schmitt et al.2010).The Ethiopian moist evergreen Afromontane forests (MAFs), which are part of the Eastern Afromontane biodiversity hotspot, are home to many economically important species, including wild coffee (Coffea arabica).These forests occur mainly in the humid southwestern parts of the country and characteristically comprise species such asPouteria adolfifriedericiiand the spiny tree fern,Alsophila manniana(Friis 1992; Friis et al.2011).

Tropical forests, being species-rich, provide a wide range of products and services including several species for food, medicine, and construction (Thomas and Baltzer 2002).Unfortunately, the biological wealth of these forests is rapidly deteriorating or lost each year due to deforestation, agricultural expansion, fire, and the development of infrastructure (Myers et al.2000).Like many tropical forests, the moist evergreen Afromontane forests of Ethiopia have been threatened by anthropogenic pressures over the last several decades.Poverty and increasing populations are among the drivers of anthropogenic pressures.Large-and small-scale coffee and tea plantations were major threats to these forests (Reusing 2000; Tadesse 2010), resulting in shrinkage of the forests and decline of associated species, including wild coffee, the reservoir of the wild gene pool (Senbeta 2006; Hundera et al.2013).The anthropogenic pressures on the Jorgo-Wato Forest (JWF) are not much different from national scenarios.However, there is scarce information on the vegetation of the JWF.Information such as species diversity, population structure, and regeneration is vital for understanding, planning, and management of the JWF.This research was carried out to assess species composition, population structure, regeneration, and management status of the JWF.

Materials and methods

Study site

Jorgo-Wato Forest is a state forest in Nole Kaba District of west Wollega in Oromia Region, Ethiopia located between 8°40′35′′ N and 8°48′56′′ N latitude and 35°56′20′′ E and 35°56′26′′ E longitude, covering an area of 8524 ha between 1950 and 2584 m a.s.l.(Fig.1).Jorgo-Wato Forest and surrounding areas experience a warm climate.This forest was one of the National Priority Forest Areas (NFPAs) of Ethiopia (Reusing 1998), protected by the Government and forest communities.According to Friis et al.(2011) the Jorgo-Wato Forest is part of the moist Afromontane forests of Ethiopia.

Fig.1 Ethiopia and Oromia Region (a) showing Nole Kaba District in west Wollega b and Jorgo-Wato-Forest

Vegetation sampling

Systematic sampling was undertaken between January 2015 and January 2016 to gather floristic data following Kent and Coker (1992).Eight transects were established from the highest elevation in north, east, south, and west directions and northeast, southeast, southwest and northwest.Seventy-three 20 m × 20 m plots were sampled along transects at every 50-m altitudinal drop.In each plot, stem number, diameter at breast height (dbh) (1.3 m) and height of wood species with dbh ≥ 2.5 cm were recorded following Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg (1974).Five 2 m × 2 m subplots (four at the corners and one at the center) were sampled within each plot to enumerate woody seedlings below 1 m height and saplings dbh < 2.5 cm.Herbarium specimens of herbaceous and woody species in and outside plots and subplots were collected and identified at the National Herbarium, Addis Ababa University, for compilation of floristic list of the JWF.In addition, information on anthropogenic activities in forest and management efforts was gathered through group discussions with 48 elders (35 males, 13 females) following Martin (1995).

Vegetation data analysis

Forest structural variables such as density (D) were computed as the total number of individuals of a species (dbh ≥ 2.5) per hectare (ha-1).Frequency (F) is the percentage of the number of times a species occur in plots per total number of plots.Basal area (Ba) was determined from dbh measurements as follows.

where π=3.14;Bais basal area; dbh is diameter at breast height.

Relative density (RD), relative frequency (RF), and relative dominance (RDO) were computed for each species using the following:

whereRDis elative density,diis density of theith species, anddtthe total density of all species in the sample.

whereRFis relative frequency,fiis the frequency of theith species, andftis the total frequency of all species in the sample.

wherebaiis the basal area of theith species andbatis the sum of the basal area of all species in the sample.

The Importance Value Index (IVI) for each species was determined by adding the relative values of density, frequency and dominance (IVI=RD + RF) + RDO following Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg (1974) and Kent and Coker (1992).Spearman correlation in SPSS (2016) version 24.0 was used to determine the relationships between structural variables (density and basal area).

The population structure of plant species is usually described in terms of diameter (dbh) and life stages of woody individuals (Rao et al.1990).In the present study, individuals with dbh ≥ 2.5 cm were recorded in nine dbh classes (1=2.5-12.5, 2=12.6-22.5, 3=22.6-32.5, 4=32.6-42.5, 5=42.6-52.5, 6=52.6-62.5, 7=62.6-72.5, 8=72.6-82.5, 9=> 82.6 cm) and height classes (1=1.5-5, 2=5.1-10, 3=10.1-15, 4=15.1-20, 5=20.1-25, 6=25.1-30, 7=30.1-35, 8=35.1-40, 9=40.1-45 m) following Peter (1996).Woody species (dbh ≥ 2.5) were classified following Raunkiær (1934) frequency classes.Seedling and sapling densities dbh < 2.5 cm were compared with the mature woody species.The regeneration status of woody species in general, and that of the trees in particular, was determined based on densities and presence or absence of seedlings and saplings following Khan et al.(1987).

Results

Species composition

Jorgo-Wato Forest has diverse species, 237 species of vascular plants from 192 genera and 82 families.Of these, 10 were endemic to Ethiopia.The majority of the species (221, 93%) were angiosperms while 15 (6%) were pteridophytes, and one species (< 1%) a gymnosperm.Fabaceae (27 species), followed by Asteraceae (21) and Acanthaceae, Lamiaceae and Poaceae (11 species each) were the most species-rich families.The top ten species rich-families contributed 50% to the total species.In terms of growth form, herbs constituted the highest proportion (119, 50%), followed by shrubs (58, 25%), trees (39, 16%) and lianas (21, 9%).

Population structure and regeneration

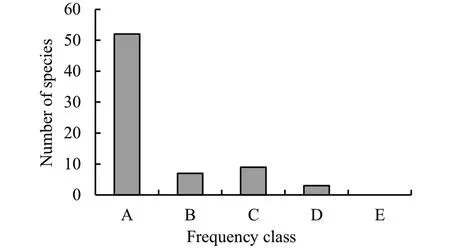

A total of 4313 individuals (dbh ≥ 2.5 cm) with overall density of 1,477 ha-1were recorded.These were distributed among 69 species, 64 genera, and 39 families.The growth forms were shrubs (45%) followed by trees (39%) and lianas (16%).The most abundant woody species (dbh ≥ 2.5 cm) wereDracaena afromontana, Chionanthus mildbraedii,Syzygium guineensesubsp.afromontanum, Maytenus gracilipes,andLandolphia buchananii.Densities of species varied between 0.3-283.6 individuals ha-1, with the mean density 21.4 ± 5.1 ha-1.The highest density was recorded forDracaena afromontana(283.6 ha-1), followed byC.mildbraedii(132.9 ha-1),S.guineensesubsp.afromontanum(131.8 ha-1),Pouteria adolfi-friedericii(101.7 ha-1).M.gracilipes(87.3 ha-1) andL.buchananii(60.3 ha-1).These six species together accounted for 44% of the total stem density ha-1.In terms of occurrence, 53 species (76.8%) were in the lowest Raunkiaer’s frequency class A (0-20%) (Fig.2).Species showing the highest densities were the most frequent and were placed in frequency class D (61-80%).The highest frequency was recorded forD.afromontana, P.adolfi-friedericiiandS.guineensesubsp.afromontanum(67.1% each).

Fig.2 Distribution of species in different Raunkiær’s frequency classes (A=1-20%; B=21-40%; C=41-60%; D=61-80%; E=81-100%)

The total basal area of the individuals dbh ≥ 2.5 cm was 62.7 m2ha-1.The species with the largest basal areas werePouteria adolfi-friedericii(30.2 m2ha-1),S.guineensesubsp.afromontanum(8.1 m2ha-1),Ficus sur(5.0 m2ha-1) andCroton macrostachyus(4.3 m2ha-1).These four species accounted for 75.8% of the total basal area while the remaining 65 species contributed 24.2%.The basal area (dominance) of the individuals was significantly correlated (r=0.75, N=69,p< 0.05) with stem density.The Importance Value Index (IVI) of the species (dbh ≥ 2.5 cm) varied between 0.17 and 37.7 (Table 1), with few species showing IVI values greater than 10 (Table 1).

Table 1 The most ecologically important species in Jorgo-Wato Forest

In terms of dbh size class distribution, the majority (77%) of individuals were in the smallest class (2.5-12.6 cm).The growth forms of the woody species were largely shrubs (45%), followed by trees (39%) and lianas (16%).The number of individuals and species consistently decreased with increasing dbh classes (Fig.3a and b).Species with the largest dbh values wereP.adolfifriedericii(207 cm),Schefflera abyssinica(170 cm),F.sur(152.9 cm) andC.macrostachyus(124.2 cm).

Fig.3 Distribution of a individuals and b species across dbh classes (1=2.5-12.5, 2=12.6-22.5, 3=22.6-32.5, 4=32.6-42.5, 5=42.6-52.5, 6=52.6-62.5, 7=62.6-72.5, 8=72.6-82.5, 9=> 82.6 cm)

With regards to height distribution, the height of woody species ranged from 1.5 to 45 m, with a mean of 4.2 m.Similar to dbh class, the majority were in the first (1.5-5 m) height class (Fig.4).The first and second height classes together accounted for 62% of the total individuals recorded in JWF.

Fig.4 Distribution of individuals (dbh ≥ 2.5 cm) across height classes (1=1.5-5, 2=5.1-10, 3=10.1-15, 4=15.1-20, 5=20.1-25, 6=25.1-30, 7=30.1-35, 8=35.1-40, 9=40.1-45 m)

The overall distribution patterns of individuals across dbh and height classes showed a definite reverse-J pattern.Further analysis of tree population structure, however, identified three different patterns (Fig.5a-c).The first pattern (reverse-J) was depicted by many tree species includingAlbizia gummifera, Albizia schimperiana,Allophylus abyssinicus,Apodytes dimidiata,Bersama abyssinica, Cassipourea malosana, Celtis africana,Croton macrostachyus, Ehretia cymosa, Ekebergia capensis, Ficus sur, Ilex mitis, Macaranga capensis, Maytenus addat, Millettia ferruginea, Olea capensissubsp.macrocarpa, Olea welwitschii, Pouteria adolfi-friedericii, Prunus africana,Syzygium guineensesubsp.afromontanum,andVeprisdainellii.These species have many individuals in the first dbh class with declining numbers in larger ones (Fig.5a).

Fig.5 Distribution of individuals in different dbh classes (a-c)

The second pattern (spread pattern) (Fig.5b) was depicted byPolyscias fulvaandCordia africana.These species showed a few individuals in intermediate classes but none in the first and last classes.The last pattern (Fig.5c) was illustrated bySchefflera abyssinicain which few individuals were present only in the last dbh class but none in lower classes.

With regards to natural regeneration, 58 species represented at the juvenile phase (seedlings and saplings).Of these, 40 species represented at both seedlings and saplings; 9 represented at seedlings; 9 at saplings.The total seedling density was 16 924, with a mean density of 352.0 ± 97.7 individuals ha-1.Similarly, the total sapling density was 11 219, with a mean of 229.0 ± 61.4 individuals ha-1.The highest seedling and sapling densities were contributed byL.buchananii,V.dainellii,andD.afromontana, accounting for 47.6% and 40.7% of the total seedlings and saplings densities, respectively.Among the tree species,A.gummifera, B.abyssinica, O.welwitschii, P.adolfi-friedericii, P.africana,andS.guineensesubsp.afromontanumshowed the highest seedling and sapling densities next toV.dainellii.In contrast,C.africana, Alsophila manniana, M.addat, P.fulva,andS.abyssinicawere species that lacked regeneration.The overall population structure of seedlings, saplings, and mature individuals showed a reverse-J pattern.

Anthropogenic factors and management of Jorgo-Wato Forest

Illegal harvesting, fire, grazing, and expansion of coffee farms were identified as anthropogenic impacts on Jorgo-Wato Forest (JWF).Expansion of coffee farms into the forest and grazing were made possible due to conflicts over the ownership of some forest lands.Since 2013, a Participatory Forest Management (PFM) program has been introduced with shared responsibilities between local communities and the government.It was introduced to improve forest management by improving the livelihoods of people and resolving forest use conflicts.As part of the co-management agreement, the government agency (Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise) agreed to benefit the communities living adjacent to the forest through creating job opportunities and developing needs-based infrastructure by sharing 5% of the money from the commercialization of plantation trees.The communities on their part agreed to protect and maintain the forest against anthropogenic disturbances.Following the agreement, the forest was categorized into specified (10-20 ha) block sizes for which 90-120 household groups were formed to manage.However, the government agency continued to sell plantation trees through a national bid to large wood enterprises without the participation of PFM members.In addition, there was a lack of government commitment to implement the negotiations and to resolve any of the communities’ livelihood needs.As a result, some members of the local community continued to claim possession in parts of the forest that had previously been demarcated.Evidently, the expansion of coffee farms into the claimed forest parts were noted, and illegal cutting of trees for timber, farm implements, and beehives is still continuing.Among the species,Cordia africanaandPouteria adolfi-friedericiihave been selectively harvested for timber, whileOlea welwitschiihas been felled for its aromatic bark which is used for making beehives.

Discussion

Species composition

Jorgo-Wato Forest is home to a wide variety of plants, including endemic and economically important species.The species are largely composed of angiosperms (93%), the dominant plant group of Ethiopian flora.The species-rich families of JWF are also among the top dominant families of the Ethiopian flora (Kelbessa and Demissew 2014).Among endemic species,Bothriocline schimperi, Lippia adoensis, Millettia ferrugineasubsp.ferruginea, Maytenus addat, Solanecio gigas, Vepris dainellii,andVernonia leopoldiwere recorded in the IUCN Red List of threatened plants under different threat categories (Vivero et al.2005).This necessitates the strengthening of JWF conservation.In terms of ecological dominance and abundance of the species, there are variations among the moist, evergreen Afromontane forests.For example,Dracaena afromontana,Chionanthus mildbraedii, andPouteria adolfi-friedericiiare dominant and abundant in the JWF whileSchefflera abyssinica,Polyscias fulva,Croton macrostachyus,Millettia ferruginea,Vepris dainellii,Prunus africana,Galiniera saxifrage,andOlea welwitschiiare dominant species in Gera Forest (Mulugeta et al.2015).Furthermore, wild coffee (Coffea arabica) was rarely found in the JWF while occurring abundantly in Yayu, Bonga, Berhan-Kontir, and Harena forests between 1,300 and 1,600 m altitudes (Woldemariam 2003; Senbeta et al.2014).

Population structure and natural regeneration

Size class distribution of individuals with dbh ≥ 2.5 cm showed the highest numbers of individuals in the lowest dbh classes and declining numbers towards the larger classes.The structure portrayed was a pattern of reverse-J distribution across size classes.Such a pattern of individuals indicates a healthy population structure (Saxena and Singh 1984; Khan et al.1987; Senbeta 2006; Tesfaye 2008).The declining number or missing of individuals towards the larger classes is indicative of various disturbances (Saxena and Singh 1984), or could be due to mortality.The Jorgo-Wato Forest has experienced logging pressure in the past.Timber trees had been extracted from the forest (Pers.comm.with elders).P.adolfi-friedericiiandC.africanawere the main timber species and are still illegally removed.Other species such asO.welwitschiiare selectively harvested for their aromatic bark which is often used to make beehives for bee attraction.This species has also been subjected to similar pressure in the Gera Forest in Jimma zone (Mulugeta et al.2015).Numerous other trees/shrubs have been illegally harvested for construction and farm implements.Studies elsewhere also showed that increasing disturbance contributes to the declining number of individuals (Sagar et al.2003; Nath et al.2005; Senbeta 2006).

Species frequency analysis showed that most of the species recorded in this study were in the lowest frequency class while a few were in the highest frequency class.Previous reports indicate that most tropical forest species (Ninan 2007; Barbara 2008), including Afromontane species, are rare and restricted in their distribution (Senbeta et al.2014).The low frequency or restricted distribution of species in the JWF could be due to a combination of biological or ecological characteristics such as lack of suitable niches (Pärtel et al.2005) and/or anthropogenic disturbances (Sagar et al.2003).These factors could also contribute to variations in the basal area between species.The density and age of species also directly contribute to the variability in basal area.Species with many individuals, including large-sized ones, have a high contribution to total basal area (Sahu et al.2008).Variations in diameter limits considered for sampling could also result in variations in the number of individuals and could, therefore, have an impact on total basal areas.Factors affecting structural variables (density, frequency, basal area) therefore, influence the importance value index (IVI).Those species which showed high IVI values are considered as ecologically dominant species.Hence, they have a significant controlling influence over ecological functions, space, and resource use due to their number, size or productivity.Species dominance is often related to the existence of a suitable niche and adaptability of the species to a wide range of niches (Kadavul and Parthasarathy 1999).The dominant species recorded in this study have also exhibited high ecological dominance in Belete Forest (Gebrehiwot and Hundera 2014) and Bonga Forest (Senbeta 2006).The dominance of a species in geographically distant forests could be due to shared environmental factors or it could be due to the species’ adaptability to a wide range of niches.Often such species are less prone to anthropogenic disturbances (Senbeta 2006) compared to species with low IVI (low ecological importance) that could easily be vulnerable to the risk of extinction.

With regards to the regeneration of JWF, the proportion of seedlings was greater than that of saplings, which in turn much higher than that of mature woody plants.Such a pattern of individuals indicates good regeneration of a forest (Saxena and Singh 1984; Khan et al.1987; Senbeta 2006; Tesfaye 2008).Although overall higher densities of seedlings and saplings were documented, some species showed few or no juveniles, indicating poor or no regeneration.For example,C.africana, M.addat, P.fulva,andS.abyssinicalacked seedlings and saplings.These species have faced similar recruitment problem in Yayu Forest (Woldemariam 2003), Wondo Genet Forest (Kebede et al.2012), Jibat Forest (Burju et al.2013), Masha Forest (Assefa et al.2013) and Gera Forest (Mulugeta et al.2015).The low number or absence of the juvenile phase could be due to a lack of suitable environmental conditions for seed germination and/or seedling development.For example, Tesfaye (2008) identified understory light environment, seedling herbivory, and human disturbances as major factors affecting the regeneration of forest species.Senbeta (2006) suggested depletion of seed by seed predators may result in poor/or no regeneration.Woldemariam (2003) and Schmitt (2006) noted that seeds of pioneer species such asC.africananeed germination disturbance and relatively large canopy gaps for regeneration.After germination seedlings are susceptible to damages, resulting in high mortality (Turner 2004).Similarly, seeds of secondary forest species such asP.fulvaneed canopy gaps after which the seedlings grow rapidly and soon reach large sizes (Schmitt 2006).In the case ofS.abyssinica,its seeds require tree forks and/or places that are rich in plant detritus to store water for germination (Kelbessa and Soromessa 2008).A study by Abiyu et al.(2013) further reported that rot holes, branch forks and moss layers on the host trees are important microsites for the successful establishment ofS.abyssinicaand about 70% of these microsites are in the lower one-third of the tree height.Whatever the case, species that showed poor/or a lack of regeneration may be at risk in the future and should be considered for enrichment planting.

Anthropogenic factors and management of the JWF

Participants of group discussions reported that the JWF is viewed as the main source of their livelihood needs, including food, medicine, and water among other ecosystem services.The informants showed a strong sense of ownership and determination to protect the forest, except for some border disputes during forest delineation.The local communities had expected participatory forest management to resolve their problems while enhancing the management of the forest.However, implementation of the program was falling short of their aspirations.As an approach, PFM aimed to reduce anthropogenic pressures or to manage the forests by improving the livelihoods of participating households.These include activities such as income diversification, value chain development, benefit-sharing, increased agricultural production and planting trees outside the forest to compensate any lack of access to forest (FAO 2011).In this study, it was understood that PFM has not been properly introduced and implemented by the Oromia Forest and Wild Life Enterprise.The agreement has also not been accompanied by bylaws and management plans.Awareness and proper procedures for implementing PFM must therefore, be put in place on the basis of mutual trust and without violating community rights.Elsewhere, in the Bonga Forest where PFM properly implemented (Gobeze et al.2009), it has improved livelihood incomes and forest conservation.Ameha et al.(2014) also reported an improved forest management status after the introduction of PFM in five sites in Oromia and South Nation and Nationalities People Regional States.Therefore, valuable experiences/lessons should be taken from such initiatives to improve the JWF management.

Conclusions and recommendations

Jorgo-Wato Forest has a high diversity of species and could be considered as one of the country’s centers of plant diversity.The population structure of the forest consists of many young woody individuals in lower diameter and height size classes, revealing a reverse J-pattern, indicative of good regeneration or recruitment.However, most of the species showed a low importance value index which implies that these species are rare.Rarity coupled with the existing anthropogenic impacts necessitates the strengthening of conservation programs.Therefore, as part of forest management, monitoring and enrichment planting is necessary, along with curbing illegal harvesting.Selling some plantation trees and timber products to local communities and local wood enterprises at affordable prices could reduce or curb illegal logging.

Jorgo-Wato Forest and surrounding areas have high potential for apiculture, tourism, coffee, and agroforestry, including fruit trees.These alternative livelihood sources could, therefore, be considered to increase the participation of local communities in participatory forest management (PFM).The Oromia Forest and Wild Life Enterprise should implement PFM based on mutual trust and respect for the community’s rights.

AcknowledgementsThe first author would like to acknowledge the logistic support (sponsorship, research funding) of the Ethiopian Bioiversity Institute through the ABS Capacity Building Medicinal Plant Project.The Department of Biology and Plant Biodiversity Management, Addis Ababa University, is greatly acknowledged for hosting this research.We are also very grateful to community informants, field guides and local administrators for their cooperation during data collections.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- A novel NIRS modelling method with OPLS-SPA and MIX-PLS for timber evaluation

- The dissemination of relevant information on wildlife utilization and its connection with the illegal trade in wildlife

- Endangered lowland oak forest steppe remnants keep unique bird species richness in Central Hungary

- The distribution patterns and temporal dynamics of carabid beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in the forests of Jiaohe, Jilin Province, China

- The disease resistance potential of Trichoderma asperellum T-Pa2 isolated from Phellodendron amurense rhizosphere soil

- Genotype-environment interaction in Cordia trichotoma (Vell.) Arráb.Ex Steud.progenies in two different soil conditions