Dipper’s Handle Returns to Yin and the Year of the Tiger Begins

2022-01-22ByShuPei

By Shu Pei

Are you in the Northern Hemisphere? If so, whether you are in the United States, Canada, Russia, the UK or China, you can look up at the stars on clear nights during this period and search for the Bigger Dipper — the seven bright stars of the constellation Ursa Major. You will find that the handle will gradually shift its direction from the north to the east, and when it arrives at, or rather returns to, the position of “Yin” (due northeast), you will know it is the Chinese New Year or the Spring Festival. That’s why the day is also called “Dipper’s Handle Returns to Yin” (or “Doubing Gui Yin”).

On a clock or watch, you will see an hour hand and a second hand move around showing you the time. In the same vein, the Bigger Dipper revolves around a “dial”; instead of 12 numbers, it points to the 12 directions of “Zi, Chou, Yin, Mao, Chen, Si, Wu, Wei, Shen, You, Xu and Hai”, falling on the position of Yin on the day of each Chinese New Year before restarting the whole process again.

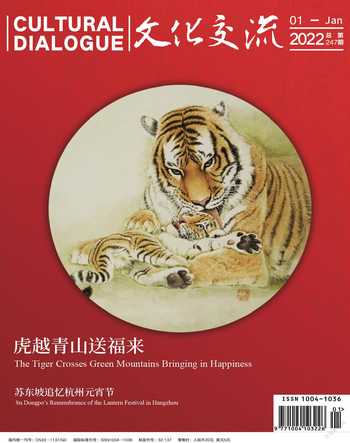

The number 12 is truly a magic number in traditional Chinese culture: a day is divided into a cycle of 12 shichen (a unit of two hours), a year into 12 months, and a cycle of 12 zodiac animals. In the Year of the Tiger, a year of renewal and dynamism, let’s keep our fingers crossed that the world will get rid of diseases and illnesses.

The tiger has long been a revered animal throughout the Chinese history. From hufu, or tiger tally, used by military commanders to tiger posters hung in ordinary households, from tiger-head hats and shoes worn by children to spring couplets extolling the tiger, “tiger worshipping” can be seen everywhere. Why not we take a look at the traditions of the Chinese New Year in preparation for the upcoming Spring Festival of the Year of the Tiger?

Also called “Sui Shou” (literally “start of the year”) in ancient times, the Spring Festival is both the end of the last year and the beginning of the new year. As the Chinese people bid farewell to winter and embrace spring, there are all sorts of traditions and rituals.

First, out with the old. On every 23rd or 24th day of the 12th lunar month — the last month in the calendar, people all over China would already begin their preparations. Known as “Xiao Nian” (literally “Minor New Year” or “Little New Year”), the day is considered to be the prologue to the Chinese New Year celebrations, with family members busy buying goodies, cleaning the house and drawing traditional Chinese New Year prints, and so on. Those who are far away from home are rushing to return, and those already at home are gearing up for the big day.

Then, on the Chinese New Year’s Eve, people would gather together to talk about the failures and successes in the past year and express gratitude to each other. For example, along the Taihu Lake, local villagers used to have lunch with their neighbors on the day, each bringing a dish for the occasion. Indeed, they would share with their fellow villagers on many festivals of the year, the Duanwu (or Dragon Boat) Festival, the summer solstice, among others.

But the most important of all is always the Chinese New Year’s Eve reunion dinner. Planting in spring, growing in summer, harvesting in autumn and storage in winter, that’s been the agricultural cycle for generations. In fact, it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the work of the two final lunar months, after the harvest season, would be entirely for the sake of this dinner. Rice cakes, preserved vegetable, preserved meat … would be all brought on to the dinner table, with all members of the typically four-generation family around it. Before the dinner, those of the same generation would exchange gifts with one another; the seniors or elders would give red envelopes to the younger ones; after wining and dining, and toasting to better times, the whole family would stay up all night, waiting for the arrival of the New Year.

On the morning of the New Year’s Day, the first thing to do is to honor the Guardian God of the Year called “Tai Sui”, sixty of them in total, each “on guard” for a year during China’s traditional sexagenary cycle — a traditional way of timekeeping. On the day, you will see all kinds of performances, including dragon dance, lion dance and boat boxing, in different places, you can visit the ubiquitous temple fairs, and you can enjoy whatever makes it festive. It is the Chinese New Year vibes that really matter. Afterwards, visiting kith and kin on the second and the third days, worshiping the God of Wealth on the fifth day … until the Lantern Festival on the fifteenth day comes to an end, when the Chinese New Year celebrations are considered fully finished.

For the Chinese people, the Chinese New Year is the “most expensive spiritual luxury”, on which they are willing to not only spend a lot of money and effort, but invest in much thought and love. All because of a strong sense of family.

The Year of the Tiger is knocking on the door. Are you on your way home?