有氧运动对记忆的影响及其神经生物学机制*

2022-01-20柯金宏

柯金宏 汪 波

有氧运动对记忆的影响及其神经生物学机制*

柯金宏 汪 波

(中央财经大学社会与心理学院, 北京 100081)

有氧运动是氧气充足时运用大型肌肉群进行有节奏的持续运动。有氧运动可以加快工作记忆任务中的反应速度; 在记忆编码前和记忆巩固阶段进行高强度有氧运动有助于提升情景记忆; 高强度有氧运动可以促进内隐记忆。有氧运动可以促进神经营养因子的产生, 引起长时程增强, 激活海马等与记忆相关的脑区并促进神经元再生。未来可探究有氧运动开始和持续时间的影响、有氧运动强度和认知参与的影响、有氧运动对不同年龄性别群体的影响以及脑源性神经营养因子的中介作用, 从而深入揭示有氧运动对记忆的影响及其神经生物学机制。

有氧运动, 记忆, 神经生物学机制

有氧运动是一种在氧气充足的情况下, 运用大型肌肉群进行有节奏的持续运动。心率储备(heart rate reserve, HRR)和摄氧量储备(oxygen uptake reserve, VO2R)常作为衡量有氧运动强度的指标, 低强度为30%至39% HRR或VO2R, 中强度为40%至59% HRR或VO2R, 高强度为60%至89% HRR或VO2R (American College of Sports Medicine, 2016)。有氧运动的形式多种多样。在室内可借助跳绳、固定式单车、跑步机等器材进行有氧运动; 在室外可通过健步走、跑步、轮滑、骑单车、游泳等方式进行有氧运动(American Heart Association, 2018)。

有氧运动有助于提升记忆, 缓解因压力(Loprinzi & Frith, 2019b)、高热量饮食(Loprinzi, Ponce, et al., 2019)、高血压(陈静等, 2020)以及毒品成瘾(李夏雯等, 2019, 11月)等诱发的记忆损伤。但是, 因为时间少和场地不足, 我国仍有超过一半的成年人几乎没有体育锻炼(国家体育总局, 2015)。研究发现, 儿童久坐行为和工作记忆的下降呈正相关(Lopez-Vicente et al., 2017)。缺乏有氧运动可能对国民的记忆产生不良影响。

本文将从有氧运动对不同类型记忆的影响着手, 分别阐述有氧运动对工作记忆、情景记忆和内隐记忆的影响, 同时指出对有氧运动与记忆的关系的多个调节变量。本文还将从脑源性神经营养因子、海马等方面阐述有氧运动影响记忆的神经生物学机制。最后提出未来可探究记忆类型、有氧运动开始和持续时间、有氧运动强度和认知参与、以及性别年龄的调节作用, 并进一步探究脑源性神经营养因子的中介作用, 从而揭示有氧运动对记忆产生影响的神经生物学机制。

1 有氧运动对不同类型记忆的影响

根据保持时间的长短, 可将记忆分为短时记忆和长时记忆(Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968)。工作记忆的概念从短时记忆发展而来。根据Baddeley和Hitch (1974)提出的工作记忆模型, 工作记忆具有多个子系统, 由一个中枢系统控制语音环和视觉空间板的记忆信息。根据多重记忆模型, 长时记忆可以分为语义记忆、情景记忆和程序性记忆(Tulving, 1985)。程序性记忆是内隐记忆的一种, 除此之外内隐记忆还包括启动和经典条件反射(Goldstein, 2018)。工作记忆、情景记忆和内隐记忆是有氧运动与记忆研究中受到广泛关注的三种记忆。越来越多的证据表明, 有氧运动对这三种记忆有不同的影响。

1.1 对工作记忆的影响

元分析发现, 有2/3的研究表明有氧运动对工作记忆有显著的促进作用(Rathore & Lom, 2017), 其中多数研究发现可以提升记忆广度任务中正确回忆数字或字母的个数(Albinet et al., 2016; Basso et al., 2015; Budde et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2011; Fisher et al., 2011), 少数研究发现可以缩短反应时(Chen et al., 2014; Hogan et al., 2013)。在一个研究中, 老年人早晨进行30分钟, 强度为65%至75%最大心率(maximum heart rate, HRmax)的步行, 接着每隔30分钟久坐后再次起身步行, 比一直久坐的老年人在记忆广度任务中正确率更高(Wheeler et al., 2020)。

研究常用n-back任务测量工作记忆, 连续呈现刺激时, 被试判断当前刺激是否与之前第n个刺激相同。人们在进行工作记忆任务时存在速度和准确性的权衡。早期的元分析发现, 有氧运动可以大幅提高工作记忆任务中的反应速度, 但对准确率有小到中等程度的不利影响(Mcmorris et al., 2011)。运用事件相关电位技术可以在时间维度上发现细微的变化。相比于坐着休息的被试, 使用固定式自行车和跑步机进行有氧运动的被试在视觉工作记忆任务中表现更好, 加工速度更快; 在电生理数据结果上, 有氧运动被试比休息被试的刺激锁定偏侧预备电位(stimulus-locked lateralized readiness potential, sLRP)更早出现, 而且sLRP和反应锁定偏侧预备电位(response- locked lateralized readiness potential, rLRP)的振幅更大(Dodwell et al., 2019)。

低强度有氧运动更有利于工作记忆。存在一种假设, 在记忆编码期间, 高强度有氧运动导致认知资源分配到其他任务, 从而损害工作记忆(Dietrich, 2006)。有实验结果支持这个假设。单次高强度(80% HRR)有氧运动降低工作记忆任务的正确率, 但单次低强度(30% HRR)和中强度(50% HRR)有氧运动没有影响(Loprinzi, Day, et al., 2019)。对于儿童, 强度小于70% HRmax的有氧运动可以提升工作记忆能力和工作记忆刷新功能, 而高强度有氧运动(70%至80% HRmax或75%至85%最大摄氧量, maximal oxygen uptake, VO2max)则没有影响(董俊, 2018; 解超, 2020)。对于大学生被试, 发生在记忆编码过程中的高强度有氧运动(70%~85% HRmax)不利于工作记忆(Loprinzi, 2018), 这可能是由于单次高强度有氧运动会产生神经信号噪音(Kashihara et al., 2009)。

有氧运动所需的认知参与程度对工作记忆有积极影响。当环境不可预测时, 人们需要更多的认知参与, 此时进行的有氧运动称为开放性有氧运动(如乒乓球、羽毛球等); 而认知参与较低, 对体能和心肺功能需求相对较高的有氧运动称为闭锁性有氧运动(如跑步和游泳) (郭玮等, 2019)。有行为实验表明, 打排球比跑步更能提升工作记忆的正确率(Zach & Shalom, 2016)。另外一个研究也表明, 在视空间信息干扰任务中, 有干扰条件下开放性有氧运动老年人的正确率显著高于闭锁性有氧运动组和久坐组(郭玮等, 2019)。因此, 更高认知参与程度的有氧运动更有利于提升工作记忆。

1.2 对情景记忆的影响

情景记忆是有关特定时空环境下个体经历的记忆(Tulving, 1972)。研究可以用自由回忆或再认的形式测量情景记忆。自由回忆是被试首先学习一个词汇列表, 延迟一段时间后不凭借任何线索对学习过的词汇列表进行回忆, 而再认则是学习过一个旧的词表之后, 混入新词汇, 要求被试判断词汇是学过的旧词还是新词。

发生在记忆编码, 记忆巩固和记忆提取等不同阶段的有氧运动对情景记忆存在不同影响。实验表明, 记忆编码前进行15分钟步行比记忆巩固阶段步行的效果更好(Haynes et al., 2019)。在记忆巩固阶段进行有氧运动也有利于减少错误记忆的发生, 但还需要更强有力的证据(Loprinzi, Lovorn, et al., 2019)。元分析也支持上述结果, 在编码前有氧运动促进情景记忆, 编码时有氧运动损害情景记忆, 记忆巩固的早期和晚期进行有氧运动可以促进情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)。

现有研究不仅仅局限于探究单次有氧运动开始时间的影响, 也有多个研究考察在编码和提取阶段均开始有氧运动是否更能促进情景记忆。前人研究发现, 编码和提取所处的状态或环境相同, 更有利于记忆的提取, 这被称为编码特异性(Encoding Specificity) (Tulving & Thomson, 1973)。有研究表明, 记忆编码前和记忆巩固阶段均进行有氧运动, 和只在记忆编码前进行有氧运动的效果没有差异(Loprinzi, Chism, et al., 2019)。该研究的缺点在于没有设置休息组。另一个研究具有相容两组(编码时和提取时分别为休息−休息或运动−运动)和不相容两组(休息−运动或运动−休息), 发现相容的状态下记忆效果更好, 支持编码特异性, 但是休息−休息组的成绩与运动−运动组的成绩没有显著差异(Yanes et al., 2019)。在记忆编码时进行有氧运动, 记忆提取时的状态(休息)与编码时的状态(有氧运动)往往不相同, 因此这可能也是编码时进行有氧运动不利于提升记忆的原因之一。

只有一个运动阶段(session)的运动称为单次运动, 长期运动指有多个阶段的运动(Rathore & Lom, 2017)。与单次有氧运动相比, 长期有氧运动更有利于提升情景记忆。在一项研究中, 75名健康年轻成人被随机分配到4组(4周有氧运动且最后1天运动、4周有氧运动且最后1天不运动、只在最后1天有氧运动、完全不运动)。有氧运动内容是每周4次30分钟以上的健步走。结果表明, 仅在4周有氧运动且最后1天运动条件下, 物体再认记忆提升, 其他3个条件下被试的记忆下降(Hopkins et al., 2012), 这表明一旦终止长期有氧运动, 对记忆的促进作用也随之消失。

高强度有氧运动更有利于情景记忆。在记忆编码前和记忆巩固阶段进行强度高于76% HRmax有氧运动比低于76% HRmax更能提升情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)。对于20多岁的年轻人, 进行强度为65%~75% HRmax的有氧运动对情景记忆的促进效果最佳(Pyke et al., 2020)。

步行和跑步对情景记忆没有显著影响, 而骑行对情景记忆有促进作用(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019), 这可能由于跑步过程中更需要注意平衡和上下肢协调, 进行垂直位移, 进而身体内部产生更多的噪音干扰(张斌, 刘莹, 2019)。

前人研究发现, 情绪对记忆巩固具有一定影响, 诱发悲伤比诱发愤怒导致更好的词汇再认成绩(Wang, 2021)。有氧运动和情绪可能具有协同作用, 影响创伤性刺激记忆, 这对恐惧记忆调节和焦虑症的治疗有实际意义(Keyan & Bryant, 2019)。有研究发现, 观看车祸影片后进行10分钟步行的被试比观看影片后休息的被试报告了更多的侵入性记忆(Keyan & Bryant, 2017)。Jentsch和Wolf (2020)探究有氧运动、性别对情绪记忆的复杂交互作用。他们发现, 针对负性图片, 有氧运动促进了女性被试的记忆, 但对男性被试的记忆没有显著影响; 针对正性图片, 有氧运动促进了男性被试的记忆, 但对女性被试的记忆没有显著影响。由此可见, 有氧运动对情景记忆巩固的影响依赖于学习材料的情绪特性和性别。

1.3 对内隐记忆的影响

内隐记忆是先前经验对当前活动的无意识的影响(Schacter, 1987)。内隐记忆和外显记忆是两套相对的记忆系统, 有氧运动对外显记忆和内隐记忆存在不同的影响。有研究发现, 有氧运动和外显记忆呈正相关, 而与内隐概率序列学习呈负相关, 这对于女性更加明显(Stillman et al., 2016)。但是Eich和Metcalfe (2009)却发现, 马拉松对外显记忆有负面影响, 但有助于提升内隐记忆。启动和经典条件反射均属于内隐记忆(Goldstein, 2018)。动作记忆编码阶段中及编码阶段后既有外显、也有内隐的成分(Kantak et al., 2012), 但外显的动作技能学习依赖于工作记忆, 而独立于工作记忆的部分为内隐的动作技能学习(Jongbloed-Pereboom et al., 2017)。

在实验室研究中, 一般采用视觉运动精度跟踪任务进行测量, 即使用操纵杆控制屏幕光标快速移动到不断变化的指定目标位置(Mang et al., 2014)。一项研究以学龄儿童为被试, 采用视觉运动精度跟踪任务, 考察了记忆巩固阶段跑步对动作记忆的影响, 发现即时测试中跑步组的成绩低于休息组, 但7天后的测试中跑步组的成绩高于休息组(Lundbye-Jensen et al., 2017)。在另一项研究中, 相比于不运动的儿童, 进行单次短时间和单次长时间有氧运动之后的儿童在旋转视觉运动适应任务中的表现更好, 动作记忆保持时间更长(Angulo-Barroso et al., 2019)。因此在记忆编码前和记忆巩固阶段进行有氧运动, 均有助于促进内隐记忆, 使儿童习得新的运动技能。近期元分析发现, 单次有氧运动对动作记忆的巩固有显著促进作用, 但效应量较小(Wanner, Cheng, et al., 2020)。

单次和长期有氧运动均能促进动作记忆, 不过迄今为止只有极少数研究对长期有氧运动对动作记忆影响进行探究。在一项研究中, 38名慢性中风幸存者被随机分配到固定式单车有氧运动组或伸展运动组, 进行为期8周, 每周3次, 每次45分钟, 强度为70% HRmax的运动, 运动后用序列反应时任务即时测验。结果表明, 有氧运动组成绩显著高于伸展运动组, 但是在运动结束后的第8周进行延迟测验, 结果没有显著差异(Quaney et al., 2009)。这表明长期有氧运动对动作记忆存在相对短暂的积极影响。最新研究发现, 进行2周自行车有氧运动的健康年轻被试比没有运动的被试可以更快速地学习动态平衡任务(Lehmann et al., 2020)。

高强度(>80%最大功率输出maximal power output, Wmax, 基本单位瓦特Watt, W)有氧运动可以促进动作记忆的巩固, 而强度为40%~79% Wmax的有氧运动对动作记忆巩固没有显著影响(Wanner, Cheng, et al., 2020)。但是, 由于肌肉群均参与有氧运动和动作记忆任务, 高强度有氧运动可能导致疲劳或干扰效应, 这将使有氧运动强度的调节效应消失(Wanner, Müller, et al., 2020)。最新研究发现, 分别进行17分钟强度为60%~90% Wmax、25%~45% Wmax、和25 W自行车骑行后, 复杂动作记忆任务的表现没有显著差异(Wanner, Müller, et al., 2020)。因此, 探究高强度有氧运动的影响, 需要排除被试的认知资源超负荷和肌肉疲劳干扰因素。

经典条件反射和启动也属于内隐记忆。经典条件反射是指当中性刺激与无条件刺激多次联结后, 单独呈现中性刺激也会引发类似无条件反射的条件反射(Goldstein, 2018)。目前, 大部分动物研究考察小鼠跑步后的条件反射。有研究表明, 2至8周的跑步可以增强小鼠的恐惧条件反射(Loprinzi & Edwards, 2018)。另一项研究将声调这种中性刺激和电击联结, 随后单独呈现声调并测量条件反射, 结果表明, 单次60分钟的高强度跑步损害了小鼠的声调恐惧条件反射(Aguiar et al., 2010)。因此, 有氧运动对条件反射的影响可能取决于有氧运动的持续时间。

启动指某个启动刺激的出现影响了对随后测试刺激的反应, 比如在词干补全任务中, 启动刺激parrot会使人们补全词干par__时更可能填写(Goldstein, 2018)。只有一个研究探究了单次有氧运动对启动的影响。Eich和Metcalfe (2009)发现, 与休息组被试相比, 完成马拉松的运动员们在词干补全任务上表现更优秀。

1.4 对三种记忆影响的比较

研究发现长期有氧运动有利于工作记忆和情景记忆, 而单次有氧运动则没有显著影响(Hopkins et al., 2012; Rathore & Lom, 2017)。对于动作记忆, 现有研究表明单次和长期有氧运动均能促进动作记忆(Lehmann et al., 2020; Wanner, Cheng, et al., 2020), 但尚未有研究直接比较单次和长期有氧运动的影响。除此之外, 单次有氧运动可以促进启动效应(Eich & Metcalfe, 2009), 而没有研究探讨长期有氧运动对启动的影响。

有氧运动强度对三种记忆的影响具有差异。高强度有氧运动(大于70% HRmax)不利于工作记忆(Loprinzi, 2018), 中强度有氧运动(40%至59% HRmax)对工作记忆的促进作用最大(Roig et al., 2013)。但高强度有氧运动(大于76% HRmax)更能提升情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)。高强度有氧运动(大于80% HRmax)也可以促进内隐记忆(Wanner, Cheng, et al., 2020), 但可能导致疲劳或干扰效应(Wanner, Müller, et al., 2020)。

对于有氧运动种类, 开放性有氧运动(如排球)比闭锁性有氧运动(如跑步)更能促进工作记忆(郭玮等, 2019; Zach & Shalom, 2016), 自行车有氧运动对情景记忆有促进作用, 而跑步对情景记忆几乎没有影响(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)。自行车有氧运动有利于动作记忆(Quaney et al., 2009)。

有氧运动开始于记忆的某一阶段, 该因素对三种记忆的影响存在共性。在记忆任务编码之前进行有氧运动对工作记忆(Loprinzi, 2018)、情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)和内隐记忆(Angulo-Barroso et al., 2019)均有促进作用。在记忆编码阶段中进行有氧运动会损害工作记忆(Loprinzi, 2018)和情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019), 进行高强度有氧运动的损害作用更大(Crawford et al., 2021)。在记忆巩固阶段进行有氧运动可以促进情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)和内隐记忆(Lundbye-Jensen et al., 2017)。由于工作记忆的记忆巩固阶段较短(约为500到2000毫秒) (Ricker et al., 2018), 难以探究在工作记忆巩固阶段进行有氧运动的影响。除此之外, 目前尚未有人探究在记忆编码中进行有氧运动对内隐记忆有何影响。

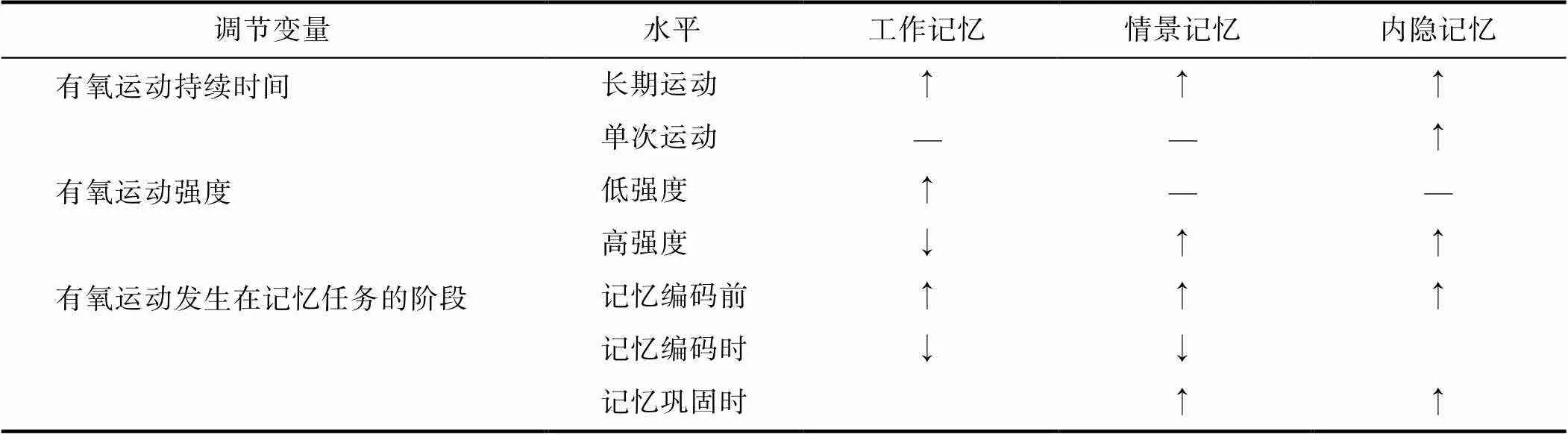

从总体上看, 有氧运动对三种记忆均有某种程度的促进作用, 但受到记忆种类、有氧运动持续时间、有氧运动强度, 和有氧运动发生在记忆任务阶段的影响, 如表1所示。

表1 有氧运动对工作记忆、情景记忆和内隐记忆的影响及其调节变量

注:“↑”表示对记忆有显著的促进作用, “↓”表示对记忆有显著的损害作用, “—”表示对记忆的影响不显著。由于工作记忆的记忆巩固阶段较短(约为500到2000 ms) (Ricker et al., 2018), 难以探究在工作记忆巩固阶段进行有氧运动的影响; 除此之外, 目前尚未有人探究在记忆编码中进行有氧运动对内隐记忆有何影响, 因此这两个地方用空格表示。

2 有氧运动影响记忆的神经生物学机制

Stillman等(2020)指出, 有氧运动可能通过多个层次影响脑和认知:分子和细胞、脑结构与功能, 以及心理状态和行为(比如睡眠)。下文从分子层面和海马结构阐述有氧运动对记忆的影响机制。

2.1 对脑源性神经营养因子的影响

有氧运动可以调节与记忆相关的激素、促进脑源性神经营养因子(brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF)的产生, 改变膜受体表达、移位, 激活数条通路, 进而改变突触的可塑性, 促进记忆(Loprinzi & Frith, 2019a)。小鼠研究表明, 肌肉在有氧运动过程中释放的乳酸代谢物穿过血脑屏障, 并在海马体中诱导BDNF的表达(El Hayek et al., 2019), 与此同时促进鸢尾素(irisin, 是纤维结合蛋白Ⅲ型结构域片段)的合成, 这也有利于促进BDNF的表达(Lourenco et al., 2019)。除此之外, FNDC5/irisin刺激了小鼠和人脑切片中的cAMP/ PKA/CREB通路, 是体育锻炼对阿尔茨海默症患者神经保护作用的潜在机制, 但是FNDC5/ irisin是否中介有氧运动对神经系统的其他影响(比如神经元再生)还有待探索(de Freitas et al., 2020)。

在动物研究中普遍发现, BDNF是有氧运动和记忆的中介(付燕等, 2015; Hyuk, 2009)。但是, 有氧运动对人类被试记忆的影响是否通过BDNF中介尚有争论。在一项元分析中, 16个人类被试研究中有7个观测到有氧运动后BDNF水平的提升(Loprinzi, 2019)。这16个研究中有10个研究对BDNF和记忆的相关进行检验, 4个研究观测到BDNF具有中介作用(Heisz et al., 2017; Maass et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2017; Winter et al., 2007)。在被试方面, 既有约22岁的年轻男性(Winter et al., 2007), 也有60至77岁的老年人, 其中男性占45% (Maass et al., 2016), 4个研究的样本均是健康被试。运动方面, 所有研究均采用发生在记忆编码前的高强度有氧运动方案, Winter等采用单次40分钟跑步, Maass等人采用3个月跑步, Wagner等和Heisz等采用6周的固定式单车有氧运动。记忆方面, 4项研究均测量情景记忆。BDNF均在最后一次有氧运动的前后立即测量。

综上, 能否发现BDNF的中介作用可能与有氧运动强度、有氧运动开始于记忆的某个阶段、记忆类型以及测量BDNF的时机有关。在记忆编码前进行高强度有氧运动有助于引起BDNF水平的变化, 进而影响人们的情景记忆。对于BDNF的测量时机, 单次有氧运动后BDNF水平升高, 但在数小时内会回到正常水平(Knaepen et al., 2010)。因此, 如果测量的时刻距离有氧运动的时段较远, 则可能观测不到BDNF水平的提升。一项研究考察了持续5周, 每周5天, 每天35分钟的有氧运动对老年人BDNF水平的影响; 在有氧运动结束平均3.8天后测量BDNF, 并未发现BDNF水平提升(Ledreux et al., 2019)。由此可见, 有氧运动引起BDNF变化的时长相对短暂, 只有在有氧运动后立即测量, 才更容易观测到BDNF水平的提升。

具有特定基因的人进行长期有氧运动, 更有助于BDNF的表达, 进而提升情景记忆。研究发现等位基因状态(即Val/Val或Val/Met基因多态性)与BDNF的表达有关, 进行4周且最后1天有氧运动的被试中, 只有Val/Val纯合子基因携带者的物体再认记忆得到显著提升, Val/Met杂合子基因携带者的记忆没有显著提升(Hopkins et al., 2012)。这进一步表明长期有氧运动提升情景记忆与BDNF表达的相关性。

2.2 对海马的影响

有氧运动通过改变分子和细胞, 影响脑结构和功能, 最终影响记忆。对于记忆编码和巩固, BDNF等分子在血清中含量的提升会引起记忆相关脑区的激活, 进而增强记忆。研究发现, 持续六个星期的自行车有氧运动导致BDNF水平的提升, 与此同时, 有氧运动组和对照组左前海马的激活模式出现显著差异, 该激活的变化与BDNF水平的变化呈正相关(Wagner et al., 2017)。除此之外, 有氧运动减轻遗忘可能有如下假设机制:单次有氧运动通过激活迷走神经或肌肉纺锤体, 由脑干传导至杏仁核、内侧前额叶皮质和齿状回, 提升这些区域的神经活动; 长期有氧运动通过促进这些区域的细胞生成、增强功能连接, 进而减弱遗忘(Crawford et al., 2020)。然而元分析并未发现有氧运动对减轻遗忘有显著作用(= 0.10; 95% CI [−0.04, 0.25],= 0.17) (Moore et al., 2020)。

单次和长期有氧运动均能使海马激活发生变化。有证据表明, 即使是低强度(30% VO2max)的10分钟自行车有氧运动, 也可以迅速增强海马DG/CA3和皮层区域的功能连接(Suwabe et al., 2018)。运用fMRI技术, 对比6个月卧床组和跳跃有氧运动组的情景记忆和海马激活的变化, 结果发现情景记忆没有显著差异, 而卧床组的海马左侧和海马旁回的血氧水平依赖信号增加, 由此推测卧床组由于身体没有活动而导致功能失调(Friedl-Werner et al., 2020)。

有氧运动不仅使海马激活, 还可以引起海马的神经元再生。研究发现有氧运动可以促进成年老鼠的海马神经元再生(van Praag et al., 2005)。成年海马神经元再生通过齿状回颗粒下区的神经干细胞池驱动, 神经干细胞从静止状态激活后产生神经祖细胞, 分裂并产生神经细胞, 最后整合到现有的海马网络中, 该过程随海马可塑性的生理需求不断调控, 随年龄增长, 神经元再生的水平缓慢下降(Bielefeld et al., 2019)。有氧运动可以暂缓甚至扭转这种下降趋势, 一项采用fMRI技术的研究表明, 有氧运动干预后小鼠和人类被试海马齿状回的脑血容量均增加, 这与神经元再生相关(Pereira et al., 2007), 此外有证据表明, 12周的健步走训练增大了年轻被试的海马前部齿状回体积(Nauer et al., 2020)。

2.3 影响不同类型记忆的机制

对于工作记忆, 单次低强度(30% VO2max)骑行可以导致空间工作记忆的改善, 同时提高前额叶的氧合血红蛋白水平(Yamazaki et al., 2017)。长期有氧运动可以通过提升心肺适能, 使其维持在最佳水平, 而良好的心肺适能通过增强额顶叶的激活, 从而提高工作记忆的表现(Ishihara et al., 2020)。在一项研究中, 34名老年人参加12周中强度(58.2% HRmax)自行车有氧运动后完成工作记忆任务, 发现右侧额顶叶的功能连接增强, 工作记忆任务的表现也显著改善, 且功能连接和工作记忆任务表现呈正相关(Voss et al., 2020)。一个以中老年人为被试的fMRI实验显示, 开放性有氧运动组比闭锁性有氧运动组空间工作记忆更好, 前额叶、前扣带皮质/辅助运动区和海马体的激活更强(Chen et al., 2019)。

情景记忆由内侧颞叶和相关脑网络维持, 增强该区域细胞和神经的沟通称为长时程增强。BDNF可以促进长时程增强, 进而改善情景记忆(Moore & Loprinzi, 2020)。具体来讲, 通过有氧运动诱导刺激肌梭和迷走神经, 海马旁和海马神经元激活将随之发生, 最终激活BDNF-TrkB通路, 激活该通路可激活细胞内通路(例如PI3K-AKT和MAPK/ERK), 磷酸化CREB, 最终诱导长时程增强(Moore & Loprinzi, 2021), 促进突触可塑性(Zou et al., 2020)。内源性大麻素系统的变化也可能是有氧运动影响情景记忆的中介机制(Loprinzi, Zou, et al., 2019)。

有氧运动对动作记忆的提升与多巴胺有关(Christiansen et al., 2019), 可以改变大脑运动皮层的电信号(Dal Maso et al., 2018), 避免其他干扰因素的影响, 对动作记忆巩固起保护作用(Beck et al., 2020; Jo et al., 2019)。有氧运动可以保护初级运动皮层免受rTMS引起的干扰, 从而保护动作记忆(Beck et al., 2020)。有氧运动也通过诱导额叶大脑区域激活增强动作记忆, 除此之外, 还改变了额颞纤维束中白质的微结构(Lehmann et al., 2020)。

3 总结和展望

未来研究可从有氧运动相关因素及其他因素入手, 探究有氧运动的影响及神经生物学机制。与有氧运动相关的因素包含有氧运动的时间(有氧运动开始的记忆阶段和持续时间)、有氧运动强度, 有氧运动的认知参与; 其他因素包含记忆种类、被试性别和年龄。

3.1 有氧运动开始的记忆阶段和持续时间的影响

何时开始有氧运动(timing)、持续多长时间(duration), 这两个问题都与时间有关。有氧运动开始于记忆任务的不同阶段具有调节作用。目前发现记忆编码前和记忆巩固阶段进行有氧运动对内隐记忆有促进作用(Angulo-Barroso et al., 2019; Lundbye-Jensen et al., 2017), 但目前尚无研究探索记忆编码过程中进行有氧运动对内隐记忆的影响。已有研究发现在记忆编码过程中进行有氧运动可能损害外显记忆, 比如工作记忆(Loprinzi, 2018)和情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)。这可能是由于分散注意造成的(Perez et al., 2014), 因为内隐记忆和外显记忆的编码均依赖于注意(Turk-Browne et al., 2006), 可以推测在记忆编码阶段进行有氧运动也可能损害内隐记忆。纳入编码过程中有氧运动这一水平, 考察有氧运动开始的记忆阶段对内隐记忆的影响, 对于深入了解有氧运动、注意和记忆三者的关系, 以及对内隐和外显记忆是否有相同影响, 具有一定的理论价值。

可以探究有氧运动持续时间, 即对比长期和单次有氧运动对内隐记忆的影响。长期有氧运动比单次有氧运动更能促进工作记忆和情景记忆, 这一结论是否能推广到内隐记忆尚待考究。因为长期和单次有氧运动可能对不同类型的记忆有利, 有小鼠研究发现单次跑步阻碍再认记忆, 而长期跑步增强了空间学习(Mello et al., 2008)。这可能是由于不同有氧运动持续时间诱导不同的基因表达, CaM‐K信号系统在单次和长期跑步中均处于活跃状态, 而长期跑步更能激活MAP‐K/ERK系统(Molteni et al., 2002)。目前的研究更多聚焦于单次有氧运动造成的影响, 但通常有长期锻炼习惯的人才会进行有氧运动, 因此对比长期和单次有氧运动的效果有助于提升研究的生态效度。

3.2 有氧运动强度和认知参与的影响

高强度有氧运动能否提升记忆仍然存在争论, 主要原因是强度需要和其他调节因素相结合进行考察, 比如有氧运动开始于记忆的阶段以及持续时间。元分析发现, 发生在记忆编码前的高强度有氧运动有助于提升情景记忆, 而记忆编码后的高强度有氧运动对情景记忆没有影响(Loprinzi, 2018)。但是由于该元分析只纳入了1篇记忆编码后进行高强度有氧运动的研究, 因此结果的稳定性还有待考证。如果在记忆编码后进行高强度有氧运动, 可适当延长有氧运动后的体能恢复时间, 再测量记忆。单次高强度有氧运动(80% HRR)损害工作记忆(Loprinzi, Day, et al., 2019), 而长期高强度有氧运动(70% VO2R)则有利于工作记忆(Jeon & Ha, 2017)。未来研究除了考察客观有氧运动强度生理指标, 还可以结合主观体力感觉(rating of perceived exertion)心理指标(Hacker et al., 2020)。

除了有氧运动强度, 有氧运动的认知参与也应受到关注。有的有氧运动需要较高的认知参与, 而有的则不需要, 更高认知参与的有氧运动可能更有利于记忆。虽然跑步有氧运动较为常见, 但是在记忆编码前跑步对情景记忆几乎没有影响(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)。打排球比跑步对工作记忆的提升更大(Zach & Shalom, 2016)。未来研究可探索其他种类有氧运动对记忆的影响, 特别是不同认知参与的有氧运动, 比如, 轮滑、球类等开放性有氧运动和跳绳、游泳、爬楼梯等闭锁性有氧运动, 可能对工作记忆有不同影响。

3.3 对多种类型记忆的影响

有氧运动对多个种类记忆的影响尚待考察。情景记忆可以细分为项目记忆和来源记忆, 项目记忆是指对于发生事件内容本身的记忆(Slotnick et al., 2003); 而来源记忆则是该事件发生时, 对于相关背景及周遭的其他事物和当时感受的记忆(Johnson et al., 1993)。未来可探究有氧运动对项目记忆和来源记忆是否存在不同影响。目前发现在记忆编码前和编码后进行单次有氧运动促进来源记忆(Delancey et al., 2019; Frith et al., 2017), 然而, 在记忆编码过程中进行有氧运动会损害来源记忆(Soga et al., 2017)。事件相关电位测量结果表明, 在有氧运动状态下可以观察到与记忆加工相关的顶叶新/旧效应, 即判断词汇是新词还是旧词的再认任务中, 出现在刺激呈现后400至900毫秒的一个脑电波, 波幅最高在8 μV以上, 休息状态下并未观察到此效应, 这可能是由于有氧运动时的源编码效率低下(Soga et al., 2017)。有氧运动对来源记忆的影响及其机制仍有待进一步探索。

有氧运动可能增强某种情绪属性的记忆。最新研究发现, 有氧运动可以增强女性的悲伤情绪图片记忆和男性的积极情绪图片记忆(Jentsch & Wolf, 2020)。未来研究可以进一步探索有氧运动对其他情绪类型记忆的影响, 在伦理允许的范围内对具有焦虑或创伤记忆的被试开展研究, 通过有氧运动干预情绪记忆, 对相应心理障碍的干预具有一定的实际意义。

在某些记忆类型上, 动物模型方面已经有充分的证据, 但是亟需人类被试的研究。比如, 有30个动物实验考察了有氧运动对视觉空间记忆的影响, 但仅有2个人类被试的实验考察这一问题(Zou et al., 2020)。在内隐记忆的启动范式方面, 仅有3个人类被试的研究, 而且尚未有研究考察长期有氧运动对启动的影响(Loprinzi & Edwards, 2018)。动物实验结论能否推广到人类, 还尚待检验。

3.4 对不同性别和年龄人群的影响

不同年龄的群体进行有氧运动, 对记忆可能有不同影响。在行为学方面, 年轻人和老年人都有将事件作为整体回忆或遗忘的倾向, 与年轻人相比, 老年人整体检索程度较低, 整体回忆随着年龄的增长而显著下降(Ngo & Newcombe, 2020)。年轻人的有氧运动习惯和情景记忆呈正相关, 而老年人有氧运动习惯和情景记忆无关(Heisz et al., 2015)。运用fMRI技术的研究表明, 儿童和成人在记忆过程中海马激活具有差异性, 随着年龄的增长, 海马的特异性程度增加(Geng et al., 2019)。因此年龄可能调节有氧运动与记忆的关系。

关于性别是否影响有氧运动与记忆的关系, 研究者并没有统一的结论。Loprinzi和Frith (2018)总结了男女在记忆方面存在差异的心理和生理原因, 心理原因包括女性的情绪强度更高, 认知风格上女性比男性的记忆编码更加细节化, 生理原因包括男女性在雌性激素水平、海马、额叶和颞叶激活水平的差异。在行为学方面, 研究发现有氧运动可以增强女性的悲伤情绪图片记忆和男性的积极情绪图片记忆(Jentsch & Wolf, 2020)。然而, 一篇情景记忆的元分析并未发现性别的调节作用(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)。未来研究可以关注有氧运动对记忆影响的性别差异。

3.5 神经生物学机制

成熟的BDNF (mature BDNF, mBDNF)是在不成熟BDNF (proBDNF)的基础上被酶促修饰形成的, 有研究发现, 单次高强度自行车有氧运动(85% VO2R)可以提升mBDNF而非proBDNF, 但有氧运动后Val/Met杂合子携带者的mBDNF浓度比Val/Val纯合子携带者的浓度更低(Piepmeier et al., 2020)。尽管有氧运动不利于提升Val/Met杂合子携带者的情景记忆, 但是有研究发现大量的有氧运动可以抵消Met基因对工作记忆的不利影响(Erickson et al., 2013)。因此Val/Met杂合子携带者同样需要进行有氧运动以提升工作记忆。未来研究可以聚焦于如何进行有氧运动才能改善Val/Met杂合子携带者的记忆, 以及是通过何种机制改变的。

目前的研究大多针对情景记忆, 较少研究考察BDNF在有氧运动和内隐记忆之间的中介作用, 研究结果尚存在分歧。有研究发现骑自行车后1小时和7天的BDNF水平更高, 和在视觉运动追踪任务中更好的表现呈正相关(Skriver et al., 2014)。但也有研究发现有氧运动后BDNF和其他动作记忆任务无关(Mang et al., 2014; Piepmeier et al., 2020)。因此, 实验需要采用对有氧运动较为敏感的记忆任务, 比如用视觉运动精度跟踪任务。

高强度有氧运动可能有利于情景记忆(Loprinzi, Blough, et al., 2019)和内隐记忆(Wanner, Cheng, et al., 2020)。BDNF可能是有氧运动强度剂量效应的机制。在两个研究中, 与低强度有氧运动和控制组相比, 高强度有氧运动更能增强BDNF水平(Jeon & Ha, 2017; Piepmeier et al., 2020)。一项元分析也发现更高的有氧运动强度能引起更高的BDNF浓度(Knaepen et al., 2010)。因此有必要进行高强度有氧运动, 以提升BDNF水平, 进而提升记忆。

有氧运动强度可能影响脑结构与功能, 进而对记忆产生影响。已有小鼠研究发现, 随着有氧运动强度的提升, 海马神经元数量也线性增加(Diederich et al., 2017)。未来研究可考察有氧运动开始时间、有氧运动强度和认知参与是否对神经递质以及脑区激活产生影响, 以了解这些因素的机制。有氧运动可能通过多种神经递质影响记忆, 降低前摄抑制, 比如通过谷氨酸系统、胆碱能系统、多巴胺系统和氨基丁酸能系统等(Li et al., 2020)。应用神经成像技术可考察有氧运动对记忆相关脑区激活和体积变化的影响, Herold等(2020)建议此类研究应采用更严格的研究设计、提供精确的有氧运动方法和功能磁共振成像处理步骤描述, 分析时应用更复杂的滤波方法。研究表明左半球因年龄增长可能会出现更严重的萎缩(Taki et al., 2011), 而有氧运动对脑结构和功能的影响也出现左偏侧化, 比如健步走训练可以增大左半球的海马前部齿状回体积(Nauer et al., 2020), 自行车有氧运动引起左前海马激活模式的变化(Wagner et al., 2017), 未来研究可通过偏侧化检验, 探究有氧运动是否能维持易受衰老影响脑区的健康。

致谢:感谢Paul D. Loprinzi对本文英文摘要的细致修改。

陈静, 刘涵慧, 李会杰. (2020). 有氧运动对高血压患者血压和记忆功能的影响.(5), 709–712.

董俊. (2018). 有氧运动对学龄儿童工作记忆刷新功能影响的Meta分析.(9), 1343–1346.

付燕, 谢攀, 李雪, 王璐, 杨澎湃, 袁琼嘉. (2015). 长期有氧运动对大鼠脑衰老过程中学习记忆与海马BDNF表达的影响.(8), 750–756.

国家体育总局. (2015).. 2015-11-16取自http://www.sport.gov.cn/n316/n340/ c212777/content.html

郭玮, 王碧野, 任杰. (2019). 开放性运动锻炼老年人视空间工作记忆优势的机制研究.(10), 50–55+80.

李夏雯, 周成林, 王小春. (2019, 11月).[摘要]. 第十一届全国体育科学大会, 南京.

解超. (2020). 不同运动强度对儿童青少年工作记忆影响的Meta分析.(3), 356–360+364.

张斌, 刘莹. (2019). 急性有氧运动对认知表现的影响.(6), 1058–1071.

Aguiar, A. S., Jr., Boemer, G., Rial, D., Cordova, F. M., Mancini, G., Walz, R., ... Prediger, R. D. S. (2010). High-intensity physical exercise disrupts implicit memory in mice involvement of the striatal glutathione antioxidant system and intracellular signaling.(4), 1216–1227.

Albinet, C. T., Abou-Dest, A., André, N., & Audiffren, M. (2016). Executive functions improvement following a 5-month aquaerobics program in older adults: Role of cardiac vagal control in inhibition performance., 69–77.

American College of Sports Medicine. (2016).(10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health.

American Heart Association. (2018).. Retrieved August 23, 2020 from https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/fitness-basics/aha-recs-for-physical-activity-in-adults

Angulo-Barroso, R., Ferrer-Uris, B., & Busquets, A. (2019). Enhancing children's motor memory retention through acute intense exercise: Effects of different exercise durations., Article 2000.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02000

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In K. W. Spence, J. T. Spence (Eds.),(Vol. 2, pp. 89–195). New York: Academic Press.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60422-3

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.),(Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). New York: Academic Press.https:// doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60452-1

Basso, J. C., Shang, A., Elman, M., Karmouta, R., & Suzuki, W. A. (2015). Acute exercise improves prefrontal cortex but not hippocampal function in healthy adults.(10), 791–801.

Beck, M. M., Grandjean, M. U., Hartmand, S., Spedden, M. E., Christiansen, L., Roig, M., & Lundbye-Jensen, J. (2020). Acute exercise protects newly formed motor memories against rTMS-induced interference targeting primary motor cortex., 110–121.

Bielefeld, P., Dura, I., Danielewicz, J., Lucassen, P. J., Baekelandt, V., Abrous, D. N., ... Fitzsimons, C. P. (2019). Insult-induced aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis: Functional consequences and possible therapeutic strategies., Article 112032.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112032

Budde, H., Voelcker-Rehage, C., Pietrassyk-Kendziorra, S., Machado, S., Ribeiro, P., & Arafat, A. M. (2010). Steroid hormones in the saliva of adolescents after different exercise intensities and their influence on working memory in a school setting.(3), 382–391.

Chang, Y.-K., Tsai, C.-L., Hung, T.-M., So, E. C., Chen, F.-T., & Etnier, J. L. (2011). Effects of acute exercise on executive function: A study with a tower of london task.(6), 847–865.

Chen, A.-G., Yan, J., Yin, H.-C., Pan, C.-Y., & Chang, Y.-K. (2014). Effects of acute aerobic exercise on multiple aspects of executive function in preadolescent children.(6), 627–636.

Chen, F.-T., Chen, Y.-P., Schneider, S., Kao, S.-C., Huang, C.-M., & Chang, Y.-K. (2019). Effects of exercise modes on neural processing of working memory in late middle-aged adults: An fMRI study., Article 224.https://doi.org/10.3389/ fnagi.2019.00224

Christiansen, L., Thomas, R., Beck, M. M., Pingel, J., Andersen, J. D., Mang, C. S., ... Lundbye-Jensen, J. (2019). The beneficial effect of acute exercise on motor memory consolidation is modulated by dopaminergic gene profile.(5), Article 578.https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050578

Crawford, L. K., Caplan, J. B., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2021). The impact of acute exercise timing on memory interference.(3), 1215–1234.

Crawford, L. K., Li, H., Zou, L., Wei, G. X., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2020). Hypothesized mechanisms through which exercise may attenuate memory interference.(3), Article 129.https://doi.org/10.3390/ medicina56030129

Dal Maso, F., Desormeau, B., Boudrias, M. H., & Roig, M. (2018). Acute cardiovascular exercise promotes functional changes in cortico-motor networks during the early stages of motor memory consolidation., 380–392.

de Freitas, G. B., Lourenco, M. V., & de Felice, F. G. (2020). Protective actions of exercise-related FNDC5/Irisin in memory and Alzheimer's disease.(6), 602–611.

Delancey, D., Frith, E., Sng, E., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2019). Randomized controlled trial examining the long-term memory effects of acute exercise during the memory consolidation stage of memory formation.(3), 245–250.

Diederich, K., Bastl, A., Wersching, H., Teuber, A., Strecker, J.-K., Schmidt, A., ... Schäbitz, W.-R. (2017). Effects of different exercise strategies and intensities on memory performance and neurogenesis., Article 47.https://doi.org/10.3389/ fnbeh.2017.00047

Dietrich, A. (2006). Transient hypofrontality as a mechanism for the psychological effects of exercise.(1), 79–83.

Dodwell, G., Müller, H. J., & Töllner, T. (2019). Electroencephalographic evidence for improved visual working memory performance during standing and exercise.(2), 400–427.

Eich, T. S., & Metcalfe, J. (2009). Effects of the stress of marathon running on implicit and explicit memory.(3), 475–479.

El Hayek, L., Khalifeh, M., Zibara, V., Assaad, R. A., Emmanuel, N., Karnib, N., ... Sleiman, S. F. (2019). Lactate mediates the effects of exercise on learning and memory through SIRT1-dependent activation of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).(13), 2369–2382.

Erickson, K. I., Banducci, S. E., Weinstein, A. M., MacDonald, A. W., III., Ferrell, R. E., Halder, I., ... Manuck, S. B. (2013). The brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism moderates an effect of physical activity on working memory performance.(9), 1770–1779.

Fisher, A., Boyle, J. M. E., Paton, J. Y., Tomporowski, P., Watson, C., McColl, J. H., & Reilly, J. J. (2011). Effects of a physical education intervention on cognitive function in young children: Randomized controlled pilot study., Article 97.https://doi.org/10.1186/1471- 2431-11-97

Friedl-Werner, A., Brauns, K., Gunga, H.-C., Kühn, S., & Stahn, A. C. (2020). Exercise-induced changes in brain activity during memory encoding and retrieval after long-term bed rest., Article 117359.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117359

Frith, E., Sng, E., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2017). Randomized controlled trial evaluating the temporal effects of high-intensity exercise on learning, short-term and long-term memory, and prospective memory.(10), 2557–2564.

Geng, F., Redcay, E., & Riggins, T. (2019). The influence of age and performance on hippocampal function and the encoding of contextual information in early childhood., 433–443.

Goldstein, E. B. (2018).(5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Hacker, S., Banzer, W., Vogt, L., & Engeroff, T. (2020). Acute effects of aerobic exercise on cognitive attention and memory performance: An investigation on duration-based dose-response relations and the impact of increased arousal levels.(5), Article 1380.https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051380

Haynes, A. T., Frith, E., Sng, E., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2019). Experimental effects of acute exercise on episodic memory function: Considerations for the timing of exercise.(5), 1744–1754.

Heisz, J. J., Clark, I. B., Bonin, K., Paolucci, E. M., Michalski, B., Becker, S., & Fahnestock, M. (2017). The effects of physical exercise and cognitive training on memory and neurotrophic factors.(11), 1895–1907.

Heisz, J. J., Vandermorris, S., Wu, J., McIntosh, A. R., & Ryan, J. D. (2015). Age differences in the association of physical activity, sociocognitive engagement, and tv viewing on face memory.(1), 83–88.

Herold, F., Aye, N., Lehmann, N., Taubert, M., & Müller, N. G. (2020). The contribution of functional magnetic resonance imaging to the understanding of the effects of acute physical exercise on cognition.(3), Article 175.https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10030175

Hogan, C. L., Mata, J., & Carstensen, L. L. (2013). Exercise holds immediate benefits for affect and cognition in younger and older adults.(2), 587–594.

Hopkins, M. E., Davis, F. C., VanTieghem, M. R., Whalen, P. J., & Bucci, D. J. (2012). Differential effects of acute and regular physical exercise on cognition and affect., 59–68.

Hyuk, L. H. (2009). Effects of treadmill exercise on memory, hippocampal cell proliferation, BDNF, TrkB, and forebrain cholinergic cells in adolescent rats.(3), 403–410.

Ishihara, T., Miyazaki, A., Tanaka, H., & Matsuda, T. (2020). Identification of the brain networks that contribute to the interaction between physical function and working memory: An fMRI investigation with over 1, 000 healthy adults., Article 117152.https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117152

Jentsch, V. L., & Wolf, O. T. (2020). Acute physical exercise promotes the consolidation of emotional material., Article 107252.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2020.107252

Jeon, Y. K., & Ha, C. H. (2017). The effect of exercise intensity on brain derived neurotrophic factor and memory in adolescents.(1), Article 27.https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12199-017-0643-6

Jo, J. S., Chen, J., Riechman, S., Roig, M., & Wright, D. L. (2019). The protective effects of acute cardiovascular exercise on the interference of procedural memory.(7), 1543–1555.

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring.(1), 3–28.

Jongbloed-Pereboom, M., Janssen, A. J., Steiner, K., Steenbergen, B., & Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M. W. (2017). Implicit and explicit motor sequence learning in children born very preterm., 145–152.

Kantak, S. S., Mummidisetty, C. K., & Stinear, J. W. (2012). Primary motor and premotor cortex in implicit sequence learning – evidence for competition between implicit and explicit human motor memory systems.(5), 2710–2715.

Kashihara, K., Maruyama, T., Murota, M., & Nakahara, Y. (2009). Positive effects of acute and moderate physical exercise on cognitive function.(4), 155–164.

Keyan, D., & Bryant, R. A. (2017). Acute physical exercise in humans enhances reconsolidation of emotional memories., 144–151.

Keyan, D., & Bryant, R. A. (2019). The capacity for acute exercise to modulate emotional memories: A review of findings and mechanisms., 438–449.

Knaepen, K., Goekint, M., Heyman, E. M., & Meeusen, R. (2010). Neuroplasticity — exercise-induced response of peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor: A systematic review of experimental studies in human subjects.(9), 765–801.

Ledreux, A., Hakansson, K., Carlsson, R., Kidane, M., Columbo, L., Terjestam, Y., ... Mohammed, A. K. H. (2019). Differential effects of physical exercise, cognitive training, and mindfulness practice on serum BDNF levels in healthy older adults: A randomized controlled intervention study.(4), 1245–1261.

Lehmann, N., Villringer, A., & Taubert, M. (2020). Colocalized white matter plasticity and increased cerebral blood flow mediate the beneficial effect of cardiovascular exercise on long-term motor learning.(12), 2416–2429.

Li, C., Liu, T., Li, R., & Zhou, C. (2020). Effects of exercise on proactive interference in memory: Potential neuroplasticity and neurochemical mechanisms.(7), 1917–1929.

Lopez-Vicente, M., Garcia-Aymerich, J., Torrent-Pallicer, J., Forns, J., Ibarluzea, J., Lertxundi, N., ... Sunyer, J. (2017). Are early physical activity and sedentary behaviors related to working memory at 7 and 14 years of age?, 35–41.

Loprinzi, P. D. (2018). Intensity-specific effects of acute exercise on human memory function: Considerations for the timing of exercise and the type of memory.(4), 255–262.

Loprinzi, P. D. (2019). Does brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediate the effects of exercise on memory?(4), 395–405.

Loprinzi, P. D., Blough, J., Crawford, L., Ryu, S., Zou, L., & Li, H. (2019). The temporal effects of acute exercise on episodic memory function: Systematic review with meta-analysis.(4), Article 87.https://doi. org/10.3390/brainsci9040087

Loprinzi, P. D., Chism, M., & Marable, S. (2019). Does engaging in acute exercise prior to memory encoding and during memory consolidation have an additive effect on long-term memory function?(1), 77–81.

Loprinzi, P. D., Day, S., & Deming, R. (2019). Acute exercise intensity and memory function: Evaluation of the transient hypofrontality hypothesis.(8), Article 445.https://doi.org/10.3390/ medicina55080445

Loprinzi, P. D., & Edwards, M. K. (2018). Exercise and implicit memory: A brief systematic review.(6), 1072–1085.

Loprinzi, P. D., & Frith, E. (2018). The role of sex in memory function: Considerations and recommendations in the context of exercise.(6), Article 132.https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7060132

Loprinzi, P. D., & Frith, E. (2019a). A brief primer on the mediational role of BDNF in the exercise-memory link.(1), 9–14.

Loprinzi, P. D., & Frith, E. (2019b). Protective and therapeutic effects of exercise on stress-induced memory impairment.(1), 1–12.

Loprinzi, P. D., Lovorn, A., Hamilton, E., & Mincarelli, N. (2019). Acute exercise on memory reconsolidation.(8), Article 1200.https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081200

Loprinzi, P. D., Ponce, P., Zou, L., & Li, H. (2019). The counteracting effects of exercise on high-fat diet-induced memory impairment: A systematic review.(6), Article 145.https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9060145

Loprinzi, P. D., Zou, L., & Li, H. (2019). The endocannabinoid system as a potential mechanism through which exercise influences episodic memory function.(5), Article 112.https://doi.org/10.3390/ brainsci9050112

Lourenco, M. V., Frozza, R. L., de Freitas, G. B., Zhang, H., Kincheski, G. C., Ribeiro, F. C., ... de Felice, F. G. (2019). Exercise-linked FNDC5/irisin rescues synaptic plasticity and memory defects in Alzheimer's models.(1), 165–175.

Lundbye-Jensen, J., Skriver, K., Nielsen, J. B., & Roig, M. (2017). Acute exercise improves motor memory consolidation in preadolescent children., Article 182.https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00182

Maass, A., Düzel, S., Brigadski, T., Goerke, M., Becke, A., Sobieray, U., ... Düzel, E. (2016). Relationships of peripheral IGF-1, VEGF and BDNF levels to exercise- related changes in memory, hippocampal perfusion and volumes in older adults., 142–154.

Mang, C. S., Snow, N. J., Campbell, K. L., Ross, C. J., & Boyd, L. A. (2014). A single bout of high-intensity aerobic exercise facilitates response to paired associative stimulation and promotes sequence-specific implicit motor learning.(11), 1325– 1336.

McMorris, T., Sproule, J., Turner, A., & Hale, B. J. (2011). Acute, intermediate intensity exercise, and speed and accuracy in working memory tasks: A meta-analytical comparison of effects.(3–4), 421–428.

Mello, P. B., Benetti, F., Cammarota, M., & Izquierdo, I. (2008). Effects of acute and chronic physical exercise and stress on different types of memory in rats.(2), 301–309.

Molteni, R., Ying, Z., & Gómez-Pinilla, F. (2002). Differential effects of acute and chronic exercise on plasticity-related genes in the rat hippocampus revealed by microarray.(6), 1107–1116.

Moore, D., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2020). Exercise influences episodic memory via changes in hippocampal neurocircuitry and long-term potentiation..https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14728

Moore, D., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2021). The association of self-reported physical activity on human sensory long- term potentiation.(3), 435–447.

Moore, D. C., Ryu, S., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2020). Experimental effects of acute exercise on forgetting.(3), 359–375.

Nauer, R. K., Dunne, M. F., Stern, C. E., Storer, T. W., & Schon, K. (2020). Improving fitness increases dentate gyrus/CA3 volume in the hippocampal head and enhances memory in young adults.(5), 488–504.

Ngo, C., & Newcombe, N. (2020). Relational binding and holistic retrieval in aging..https://doi.org/ 10.31219/osf.io/y35ku

Pereira, A. C., Huddleston, D. E., Brickman, A. M., Sosunov, A. A., Hen, R., McKhann, G. M., ... Small, S. A. (2007). An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus.(13), 5638–5643.

Perez, L., Padilla, C., Parmentier, F. B., & Andres, P. (2014). The effects of chronic exercise on attentional networks.(7), Article e101478.https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0101478

Piepmeier, A. T., Etnier, J. L., Wideman, L., Berry, N. T., Kincaid, Z., & Weaver, M. A. (2020). A preliminary investigation of acute exercise intensity on memory and BDNF isoform concentrations.(6), 819–830.

Pyke, W., Ifram, F., Coventry, L., Sung, Y., Champion, I., & Javadi, A.-H. (2020). The effects of different protocols of physical exercise and rest on long-term memory., Article 107128.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2019.107128

Quaney, B. M., Boyd, L. A., McDowd, J. M., Zahner, L. H., He, J., Mayo, M. S., & Macko, R. F. (2009). Aerobic exercise improves cognition and motor function poststroke.(9), 879–885.

Rathore, A., & Lom, B. (2017). The effects of chronic and acute physical activity on working memory performance in healthy participants: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials., Article 124.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643- 017-0514-7

Ricker, T. J., Nieuwenstein, M. R., Bayliss, D. M., & Barrouillet, P. (2018). Working memory consolidation: Insights from studies on attention and working memory.(1), 8–18.

Roig, M., Nordbrandt, S., Geertsen, S. S., & Nielsen, J. B. (2013). The effects of cardiovascular exercise on human memory: A review with meta-analysis.(8), 1645–1666.

Schacter, D. L. (1987). Implicit memory: History and current status.(3), 501–518.

Skriver, K., Roig, M., Lundbye-Jensen, J., Pingel, J., Helge, J. W., Kiens, B., & Nielsen, J. B. (2014). Acute exercise improves motor memory: Exploring potential biomarkers., 46–58.

Slotnick, S. D., Moo, L. R., Segal, J. B., & Hart, J. (2003). Distinct prefrontal cortex activity associated with item memory and source memory for visual shapes.(1), 75–82.

Soga, K., Kamijo, K., & Masaki, H. (2017). Aerobic exercise during encoding impairs hippocampus-dependent memory.(4), 249–260.

Stillman, C. M., Esteban-Cornejo, I., Brown, B., Bender, C. M., & Erickson, K. I. (2020). Effects of exercise on brain and cognition across age groups and health states.(7), 533–543.

Stillman, C. M., Watt, J. C., Grove, G. A., Jr., Wollam, M. E., Uyar, F., Mataro, M., ... Erickson, K. I. (2016). Physical activity is associated with reduced implicit learning but enhanced relational memory and executive functioning in young adults.(9), Article e0162100.https:// doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162100

Suwabe, K., Byun, K., Hyodo, K., Reagh, Z. M., Roberts, J. M., Matsushita, A., ... Soya, H. (2018). Rapid stimulation of human dentate gyrus function with acute mild exercise.(41), 10487–10492.

Taki, Y., Thyreau, B., Kinomura, S., Sato, K., Goto, R., Kawashima, R., & Fukuda, H. (2011). Correlations among brain gray matter volumes, age, gender, and hemisphere in healthy individuals.(7), Article e22734.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022734

Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving, W. Donaldson (Eds.),. New York: Academic Press

Tulving, E. (1985). How many memory systems are there?(4), 385–398.

Tulving, E., & Thomson, D. M. (1973). Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory.(5), 352–373.

Turk-Browne, N. B., Yi, D.-J., & Chun, M. M. (2006). Linking implicit and explicit memory: Common encoding factors and shared representations.(6), 917–927.

van Praag, H., Shubert, T., Zhao, C., & Gage, F. H. (2005). Exercise enhances learning and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice.(38), 8680– 8685.

Voss, M. W., Weng, T. B., Narayana-Kumanan, K., Cole, R. C., Wharff, C., Reist, L., ... Pierce, G. L. (2020). Acute exercise effects predict training change in cognition and connectivity.(1), 131–140.

Wagner, G., Herbsleb, M., de la Cruz, F., Schumann, A., Köhler, S., Puta, C., ... Bär, K.-J. (2017). Changes in fMRI activation in anterior hippocampus and motor cortex during memory retrieval after an intense exercise intervention., 65–78.

Wang, B. (2021). Effect of post-encoding emotion on long-term memory: Modulation of emotion category and memory strength.(2), 192–218.

Wanner, P., Cheng, F.-H., & Steib, S. (2020). Effects of acute cardiovascular exercise on motor memory encoding and consolidation: A systematic review with meta-analysis., 365–381.

Wanner, P., Müller, T., Cristini, J., Pfeifer, K., & Steib, S. (2020). Exercise intensity does not modulate the effect of acute exercise on learning a complex whole-body task., 115–128.

Wheeler, M. J., Green, D. J., Ellis, K. A., Cerin, E., Heinonen, I., Naylor, L. H., ... Dunstan, D. W. (2020). Distinct effects of acute exercise and breaks in sitting on working memory and executive function in older adults: A three-arm, randomised cross-over trial to evaluate the effects of exercise with and without breaks in sitting on cognition.(13), 776–781.

Winter, B., Breitenstein, C., Mooren, F. C., Voelker, K., Fobker, M., Lechtermann, A., ... Knecht, S. (2007). High impact running improves learning.(4), 597–609.

Yamazaki, Y., Sato, D., Yamashiro, K., Tsubaki, A., Yamaguchi, Y., Takehara, N., & Maruyama, A. (2017). Inter-individual differences in exercise-induced spatial working memory improvement: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. In H. J. Halpern, J. C. LaManna, D. K. Harrison, B. Epel (Eds.),(Vol. 977, pp. 81–88). New York: Springer International Publishing.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3- 319-55231-6_12

Yanes, D., Frith, E., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2019). Memory- related encoding-specificity paradigm: Experimental application to the exercise domain.(3), 447–458.

Zach, S., & Shalom, E. (2016). The influence of acute physical activity on working memory.(2), 365–374.

Zou, L., Yu, Q., Liu, S., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2020). Exercise on visuo-spatial memory: Direct effects and underlying mechanisms.(2), 169–179.

Effects of aerobic exercise on memory and its neurobiological mechanism

KE Jinhong, WANG Bo

(School of Sociology and Psychology, Central University of Finance and Economics, Beijing 100081, China)

Aerobic exercise is the rhythmic and continuous use of large muscle groups with sufficient oxygen supply. The aim of this review is to summarize previous research regarding the effects of aerobic exercise on working memory, episodic memory and implicit memory, and moderators among the relationships. The following databases were used for the computerized searches: CNKI, Web of Science and PubMed. Aerobic exercise can improve processing speed in working memory tasks. Moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise before memory encoding or during consolidation can enhance episodic memory. Vigorous intensity aerobic exercise can promote implicit memory. Acute aerobic exercise can increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), induce long-term potentiation, activate hippocampus and other memory related brain areas, while chronic aerobic exercise can improve neurogenesis. Future research should focus on aerobic exercise timing, aerobic exercise duration, aerobic exercise intensity, and other moderating roles, such as cognitive engagement during aerobic exercise, gender and age, and to further elucidate the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the effects of aerobic exercise on different types of memory.

aerobic exercise, memory, neurobiological mechanism

B849: G804.8

2020-11-16

* 中央财经大学2019年度国家级大学生创新创业训练计划项目(NMOE2019110019)资助。

汪波, E-mail: wangbo@cufe.edu.cn